Abstract

Intramuscular cystic echinococcosis is a very rare occurrence. Herein we report a case of a 37-year-old patient who presented with progressive swelling of his left thigh. Ultrasound evaluation showed a multicystic, encapsulated lesion (16 × 3.5 × 8.5 cm) in the M. vastus lateralis, and serology confirmed the diagnosis of Echinococcus granulosus s.l. infection. No additional cysts were detected upon total body CT scan. The patient was treated with albendazole pre-operatively; surgical resection of the mass was then successfully performed. The patient feels well and no signs of residual infestation were seen after 2 years of follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is a parasitic infection caused by the metacestode stage of the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus. It is endemic in South America, the Middle East, some sub-Saharan African countries and western China [1, 2]. In Eurasia, CE is mainly found in the Mediterranean regions, but also in the Russian Federation and adjacent states. In Europe, the highest incidences of cystic echinococcosis in 2016 were reported in Bulgaria (4.5/100.000) [1], whereas in Austria 22 laboratory-confirmed cases of CE were reported [3]. E. granulosus adult tapeworms are usually found in dogs. Humans are only incidental hosts and are infected by the ingestion of contaminated food. In the intestine eggs hatch, the oncospheres penetrate the mucosa and are then transported to the liver or other visceral organs by the portal vein system. Consecutively, fluid-filled cysts develop, e.g., in the liver, and multiple layers form hydatid cysts (metacestode stage of E. granulosus infection). Mostly, the liver is affected, however, CE can also be frequently found in the lungs (about 17–22%). Manifestation in other organs is rare, extra-hepatopulmonary cysts mostly involve abdominal organs [4]. Intramuscular CE has been described to occur very rarely [4]. Isolated intramuscular lesions without any manifestations in liver or lungs are extremely scarce, only few studies report about a higher number of patients, e.g., one study with 11 patients in Tunisia [5] and 22 patients in Turkey [6]. Furthermore also a German study described 4 cases of muscle involvement [7], and a Spanish [8] and an Iranian [9] study reported about 13 and 11 patients with muscular CE, respectively. Due to the rarity of intramuscular echinococcosis, diagnosis and also therapy can be challenging in patients and interdisciplinary treatment is often necessary.

We herein describe the case of an Austrian patient (of Turkish ancestry), who presented with a progressive swelling of his left thigh due to intramuscular CE.

Case report

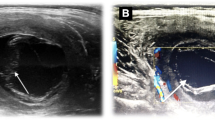

A 37-year-old male patient presented at a peripheral hospital in Austria. He had noticed a progressive swelling of his left thigh over the last years, which became rapidly enlarged over the past few weeks. Except for his asthma he had no prior medical history and did not report about recent trauma, fever or other signs of infection or local pain. The patient originated from Turkey, but has been living in Austria for more than 20 years. He returned for visiting relatives and friends to Turkey occasionally. On physical examination, a non-fluctuant, superficially not inflamed swelling with a longitudinal extension of approximately 20 cm was found in the left calf with no other associated tenderness. Upon mobilization of the limb, the mass did not reduce in size. The results of laboratory tests of the patient were all within normal ranges. Ultrasonography showed a multicystic, encapsulated lesion unambiguously suspicious of echinococcosis (Fig. 1a, b), thus the patient was referred to our department. Serology was positive for echinococcosis (ELISA against the arc 5 antigen:30 antibody units) and Western blot confirmed the diagnosis of Echinococcus granulosus infection. CT examination showed no additional cysts in the body. Treatment with albendazole was initiated and surgical resection was performed after pre-operative MRI (Fig. 1c, d).

The encapsulated mass was resected in toto and had a weight of 211 g (Fig. 2). Histopathologic examination confirmed the diagnosis of echinococcosis, thin cyst walls filled with liquid were described (Fig. 3 shows hematoxylin and eosin stains as well as periodic acid–Schiff stain and Grocott Gomori methenamine stain with corresponding legends).

Histologic stains of the resected mass with legends. 1a Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 100× magnification with typical section through the cyst wall layers of cystic Echinococcosis, namely the outer fibrous wall (FW), the laminated layer (LL) and the collapsed degenerated inner germinal epithelial layer (GL). 1b Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 9x magnification with central extensive necrosis (N), well-defined fibrous wall (FW) and remnants of skeletal muscle at the periphery (M). 2a Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 400× magnification with typical section through the cyst wall layers of cystic Echinococcosis showing parts of the laminated layer (LL) and the inner germinal epithelial layer (GL) and five shadowy roundish structures suggestive of degenerated protoscolices. 2b Periodic acid–Schiff stain, 100× magnification, showing a strong positivity in remnants (arrow) of the laminated layer, a helpful diagnostic clue. 3a Periodic acid–Schiff stain (PAS), 400× magnification, outlining the laminated layer (LL) measuring. 3b Periodic acid–Schiff stain (PAS), 400× magnification, outlining the laminated layer (LL) measuring 60.1 µm. 4a Grocott Gomori methenamine stain, 100× magnification, outlining the laminated layer (LL). 4b Positivity correlating with incorporation of chitin material in the fibrous wall (FW) which resembles the host reaction (arrow)

Post-operatively the patient developed seroma at the intramuscular resection cavity, which regressed spontaneously within weeks. At last follow-up (2 years after resection) the patient presented well without any signs of residual infection.

Discussion

Intramuscular CE is very uncommon [4, 10], intramuscular cysts have been reported in the muscles of the neck [9, 11], the arm 12,13] and the leg [6, 7, 14], and hip muscles [7, 9].

In the differential diagnosis of unusual soft tissue lesions intramuscular echinococcosis should be considered, even if the patients are oligosymptomatic and laboratory tests are normal—as in the case of our patient. Upon suspicion by imaging methods adjunctive laboratory tests, e.g., serologic tests (mostly with antibodies against crude parasite extracts) can be employed to establish the diagnosis. However, not all patients with echinococcosis are detected by serology, most probably due to clinical variables related with cyst stage, number and size [see review by Siles-Lucas [15]]. In fact, the sensitivity and specificity of serology appears to be higher for E. multilocularis than for E. granulosus [15]. Thus, these tests are supportive, but without typical radiologic findings they are inadequate per se to establish the diagnosis of CE. A recent review by Siles-Lucas and coworkers gives a very good overview of the laboratory diagnosis of Echinococcus spp., in which also other adjunctive laboratory tests and their diagnostic utility are discussed. Furthermore, this review suggests that the combination of different laboratory tests (e.g., antibody and antigen detection) or of several (recombinant) antigens might improve the performance of adjunctive laboratory methods to establish the diagnosis of CE [15].

Thus, diagnosis of intramuscular or musculoskeletal CE might be challenging, especially in patients not living in areas endemic for echinococcosis. Imaging methods like ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging are necessary, depending on the localizations of CE different imaging methods are advised, e.g., for bone cysts MRI enables better visualization of the cysts in relation to surrounding tissue [4, 16]. Ultrasonography is easy to perform and relatively inexpensive, CT on the other hand is the best option to study extrahepatic dissemination of cysts [4], especially in the abdominal region.

In central Turkey (where our patient originated from) CE is endemic in rural areas [17], while in Austria the incidence is rather low [18], and only 8 of 22 cases were autochthonous [3]. Most CE patients diagnosed in Austria originate from Mediterranean regions (especially Turkey) or the Balkan—thus, CE should be one of the differential diagnoses, even if the patient has lived for many years in Austria, but was born in endemic regions.

Our patient returned to Turkey for holidays, but did not have direct contact with animals including dogs (except for his childhood). Apart from a progressive swelling at his thigh he had no other complaints. A similar course of disease was described also in other patients with intramuscular CE [9]. Symptoms are dependent on the size and site of cysts, some patients are even asymptomatic [4].

Size and location of cysts are also important for treatment. Currently, there exist four options for treating CE: anti-infective treatment, percutaneous puncture, surgery and “watch and wait” [4, 16]. In our patient with intramuscular CE perioperative albendazole therapy with consecutive total resection of the cyst was performed. In patients with resectable musculoskeletal CE, radical resection of the affected tissue is the treatment of choice (as it is the only way to get rid of the larva) [16]. Perioperative albendazole treatment effectively decreases the rate of viable cysts as well as relapse rates [16]. A short course of anthelminthic treatment (starting at least 4 days prior surgery) is recommended in patients with CE to reduce the parasitic burden and the risk of anaphylactic shock or dissemination [16, 19].

As our patient had a really big lesion and we wanted to decrease the risk of spillage, our patient got albendazole for several weeks, which is also in accordance with WHO recommendations, which suggest a 30-day course of albendazole before surgery of cysts [19] Pre-operative albendazole treatment also resulted in a discrete reduction of the lesion size in the MRI (Fig. 1c, d) in our patient.

Skeletal involvement should be considered in patients with intramuscular CE, fortunately in our patient neither CT nor MRI indicated skeletal CE. However, involvement of bone goes along with a higher risk of relapse [4, 20] and is less sensitive to benzimidazole treatment, than cysts in other locations, and thus may require long-term administration [20].

During surgery particular diligence must be exercised to avoid rupture of the capsule of the cyst, otherwise allergic shock might occur. Therefore, only well-trained surgeons with particular experience in tumor surgery, skilled particularly in anatomy and atraumatic resection techniques should be in charge of CE resection. For cases inaccessible to surgery, anthelminthic treatment and/or percutaneous aspiration–injection–reaspiration (PAIR) represent possible alternatives [16].

In conclusion, our case report shows that not only the diagnosis, but also the treatment of intramuscular CE might be challenging and optimal treatment of the individual patient can be reached only by collaboration of all involved disciplines (surgeons, radiologists, and infectiologists/parasitologists).

References

Deplazes P, Rinaldi L, Alvarez Rojas CA, Torgerson PR, Harandi MF, Romig T, Antolova D, Schurer JM, Lahmar S, Cringoli G, Magambo J, Thompson RC, Jenkins EJ. Global distribution of alveolar and cystic echinococcosis. Adv Parasitol. 2017;95:315–493.

Romig T, Dinkel A, Mackenstedt U. The present situation of echinococcosis in Europe. Parasitol Int. 2006;55:S187–91.

Much P, Arrouas M, Herzog U. Echinococcosis. Report on zoonoses and zoonotic agents in Austria in 2016. Vienna: AGES—Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety; 2017. pp 65–67.

Kern P, Menezes da Silva A, Akhan O, Müllhaupt B, Vizcaychipi KA, Budke C, Vuitton DA. The echinococcoses: diagnosis, clinical management and burden of disease. Adv Parasitol. 2017;96:259–369.

Mseddi M, Mtaoumi M, Dahmene J, Ben Hamida R, Siala A, Moula T, Ben Ayeche ML. Hydatid cysts in muscles: eleven cases. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2005;91:267–71.

Tekin R, Avci A, Tekin RC, Gem M, Cevik R. Hydatid cysts in muscles: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management of this atypical presentation. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48:594–8.

Merkle EM, Schulte M, Vogel J, Tomczak R, Rieber A, Kern P, Goerich J, Brambs HJ, Sokiranski R. Musculoskeletal involvement in cystic echinococcosis: report of eight cases and review of the literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:1531–4.

García-Alvarez F, Torcal J, Salinas JC, Navarro A, García-Alvarez I, Navarro-Zorraquino M, Sousa R, Tejero E, Lozano R. Musculoskeletal hydatid disease: a report of 13 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73:227–31.

Geramizadeh B. Unusual locations of the hydatid cyst: a review from iran. Iran J Med Sci. 2013;38:2–14.

Akhan O, Gumus B, Akinci D, Karcaaltincaba M, Ozmen M. Diagnosis and percutaneous treatment of soft-tissue hydatid cysts. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:419–25.

Nath K, Prabhakar G, Nagar RC. Primary hydatid cyst of neck muscles. Indian J Pediatr. 2002;69:997–8.

Duncan GJ, Tooke SM. Echinococcus infestation of the biceps brachii. A casereport. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;261:247–50.

Aydin BK, Acar MA, Sumer S, Demir NA, Erkocak OF, Ural O. Primary hydatid disease of brachialis and biceps brachii muscles: a case report. Trop Doct. 2014;44:53–5.

Madhar M, Aitsoultana A, Chafik R, Elhaoury H, Saidi H, Fikry T. Primary hydatid cyst of the thigh: on seven cases. Musculoskelet Surg. 2013;97:77–9.

Siles-Lucas M, Casulli A, Conraths FJ, Müller N. Laboratory diagnosis of Echinococcus spp. in Human Patients and Infected Animals. Adv Parasitol. 2017;96:159–257.

Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA. Writing Panel for the WHO-IWGE. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2010;114:1–16.

Altintas N. Past to present: echinococcosis in Turkey. Acta Trop. 2003;85:105–12.

Auer H, Aspöck H. Incidence, prevalence and geographic distribution of human alveolar echinococcosis in Austria from 1854 to 1990. Parasitol Res. 1991;77:430–6.

Literature review by Moro PL; Oct 2018. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-echinococcosis. Accessed 23 Mar 2018.

Neumayr A, Tamarozzi F, Goblirsch S, Blum J, Brunetti E. Spinal cystic echinococcosis—a systematic analysis and review of the literature: part 2. Treatment, follow-up and outcome. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2458.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck and Medical University of Innsbruck. We thank our Department of Radiology (Innsbruck Medical University) for providing the MRI-images and the District Hospital of Reutte for providing the ultrasound images.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kurz, K., Schwabegger, A., Schreieck, S. et al. Cystic echinococcosis in the thigh: a case report. Infection 47, 323–329 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-018-1255-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-018-1255-9