Abstract

Objective

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was used to evaluate cognitive dysfunction after basal ganglia stroke, and factors affecting total MoCA score were examined.

Methods

Data were retrospectively analyzed for 30 patients with basal ganglia intracerebral hemorrhage or basal ganglia cerebral infarction, who were admitted to The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Traditional Medical University (Fujian, China) from January 2017 to March 2020. Cognitive impairment was assessed using the MoCA, and potential correlations were explored between clinicodemographic characteristics (sex, age, stroke location and etiology) and MoCA dimensions or total MoCA score.

Results

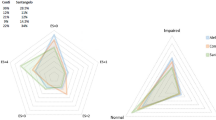

Univariate linear regression showed that the total MoCA score was significantly associated with sex, age, executive function, naming, attention, abstract generalization ability, memory ability, and visuospatial orientation. However, multivariate linear regression identified only executive function, naming, attention, memory ability, and visuospatial orientation as significantly associated with the total MoCA score.

Conclusions

We showed that the MoCA test can be used for patients with basal ganglia stroke. The total MoCA score of basal ganglia stroke was significantly associated with impairments in executive function, naming, attention, memory ability, and visuospatial orientation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Stroke is currently the second leading cause of death and the primary cause of disability worldwide [1, 2] leading to somatic motor dysfunction and cognitive decline [3,4,5]. Cognitive dysfunction after stroke severely affects recovery and quality of life, while it increases the financial burden on families and medical costs to society.

Basal ganglia stroke is a common type of cerebral infarction, while basal ganglia intracerebral hemorrhage is the most common type of intracerebral hemorrhage. Specifically, contralateral hemiplegia, hemidysesthesia, and hemianopia can occur in the basal ganglia, which consist of an inner capsule surrounded by white matter. Subcortical aphasia, in contrast, can occur in dominant hemispheric lesions.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a cognitive screening test used to detect mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease, and it is considered suitable for stroke patients [6]. In fact, the MoCA allows more detailed evaluation of cognitive function than the Mini-Mental State Examination and shows greater sensitivity for detecting cognitive dysfunction after stroke [7, 8]. Recent studies have also shown that MoCA screening for cognitive impairment after stroke is simple and effective [9] and can predict functional recovery after 3 months [10].

However, the efficacy of MoCA in assessing cognitive dysfunction specifically after basal ganglia stroke is still unclear. Therefore, in this study, we applied the MoCA to evaluate cognitive dysfunction after basal ganglia stroke and explored the potential association of MoCA subscores in different cognitive domains with the patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics.

Materials and methods

Study population

This retrospective study included patients with basal ganglia intracerebral hemorrhage or basal ganglia cerebral infarction who were admitted to The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Traditional Medical University (Fujian, China) between January 2017 and March 2020 and were older than 20 years, were diagnosed with basal ganglia cerebral infarction or cerebral hemorrhage by magnetic resonance imaging, and had the disease longer than 14 days but shorter than 3 months (recovery stage). Patients were excluded from the study if they had cognitive impairment (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease, Louis body dementia) before stroke onset; if they had cognitive impairment due to other causes, such as cerebral trauma, cerebral infarction, or hemorrhage besides basal ganglia; or if they were unwilling or unable to complete the MoCA, such as because of a severe mental disorder.

The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (ethics review number 2017- KL017-02), and all patients signed written informed consent prior to enrollment.

Observational indicators

Once patients entered the recovery phase, the Beijing version of the MoCA was used to assess their cognitive function [11], and the assessments were evaluated by a physician with expertise in MoCA evaluation. The MoCA, for which the total score can be a maximum of 30 points, assesses seven cognitive domains: visuospatial orientation, executive function, naming, attention, language function, abstract generalization ability, memory ability, and orientation ability. A total MoCA score below 26 points was considered to indicate cognitive impairment [11]. One point was added to the total MoCA score for patients with no more than 12 years of education, as they tend to perform worse on the MoCA [12].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Univariate simple linear regression was performed to determine the association of different variables with the total MoCA score, and variables that were significant in this analysis were entered stepwise into multivariate linear regression. Data were reported as mean ± SD, and regression coefficients were reported with a 95% confidence interval (CI). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 30 patients with basal ganglia stroke were enrolled (Table 1). Univariate linear regression showed that the total MoCA score was significantly associated with patients’ sex, age, executive function, naming, attention, abstract generalization ability, memory ability, and visuospatial orientation. However, multivariate linear regression identified only executive function, naming, attention, memory ability, and visuospatial orientation as significantly associated with total MoCA score (Table 2).

Discussion

Here we provide evidence that the MoCA can be used to assess cognitive impairment of patients after basal ganglia stroke, and our analysis suggests that such stroke can indeed reduce cognitive function, consistent with previous studies [13,14,15]. In addition, our analysis shows that such stroke can reduce function in multiple cognitive domains. Accurate assessment of early cognitive impairment after stroke and timely intervention are particularly important to achieve a high quality of life for patients [16, 17].

Frontal lobe infarction is the most common type of stroke, followed by infarction in the temporal lobe, occipital lobe, thalamus, and basal ganglia. Several studies have shown that the executive function is performed mainly in the frontal cortex, which is thought to be in the center of the lateral prefrontal cortex [18]. Consistent with this, patients with frontal lobe brain damage, especially in the left dorsal frontal lobe, have shown reduced problem-solving ability and difficulty in organizing and implementing plans [18]. The basal ganglia are a series of subcortical nerve tissues in the forebrain located below the anterior segment of the lateral ventricle. The motor region of the cortex can project into the basal ganglia through the thalamus and subthalamic nucleus, while the major output from the basal ganglia extends from the globus pallidus to the thalamus and from the nucleus to the motor cortex, the pre-motor cortical region, and the prefrontal cortex. Hence, the basal ganglia are not involved in the motor pathway extending from the cortex to the spinal cord, and therefore do not participate in the direct control of motion. Instead, they belong to the cortical–subcortical motor loop, which controls both motor and non-motor processes. Therefore, infarction of the basal ganglia can disrupt the anterior frontal lobe and subcortical loops similar to frontal lobe injury [19, 20], potentially affecting all cognitive functions. Basal ganglia stroke has been linked to impairment in executive function, but not attention deficits or delayed memory [18]. Indeed, our results support that basal ganglia stroke can reduce function in multiple cognitive domains of the MoCA. Linear regression suggested that basal ganglia stroke is closely related to impairments in executive function, naming, attention, memory ability, and visuospatial orientation.

Our study showed no significant differences in total MoCA score or MoCA subscores between patients who differed in stroke location (right vs. left) or etiology (cerebral hemorrhage vs. cerebral infarction). Similarly, we found that the total MoCA score was not associated with patients’ age, sex, or education level at the onset of basal ganglia stroke, in contrast to previous studies [21]. Our failure to detect an association between sex and cognitive subscores may be attributed to our small sample. Thus, further studies should be performed to clarify the potential influence of sex on cognitive impairment after basal ganglia stroke. Despite this limitation, our observations may help guide the development of more effective rehabilitation programs for patients with basal ganglia stroke.

References

Zhou M, Wang H, Zhu J, Chen W, Wang L, Liu S et al (2016) Cause-specific mortality for 240 causes in China during 1990–2013: a systematic subnational analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 387:251–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00551-6

GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators (2018) Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392:1736–1788. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7

Lees R, Fearon P, Harrison JK, Broomfield NM, Quinn TJ (2012) Cognitive and mood assessment in stroke research: focused review of contemporary studies. Stroke 43:1678–1680. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.653303

Fride Y, Adamit T, Maeir A, Ben Assayag E, Bornstein NM, Korczyn AD et al (2015) What are the correlates of cognition and participation to return to work after first ever mild stroke? Top Stroke Rehabil 22:317–325. https://doi.org/10.1179/1074935714Z

Gaynor E, Rohde D, Large M, Mellon L, Hall P, Brewer L et al (2018) Cognitive impairment, vulnerability, and mortality post ischemic stroke: a five-year follow-up of the Action on Secondary Prevention Interventions and Rehabilitation in Stroke (ASPIRE-S) Cohort. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 27:2466–2473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.05.002

Ozzoude M, Ramirez J, Raamana PR, Holmes MF, Walker K, Scott CJM et al (2020) Cortical thickness estimation in individuals with cerebral small vessel disease, focal atrophy, and chronic stroke lesions. Front Neurosci 14:598868. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.598868

Rosca EC, Cornea A, Simu M (2020) Montreal Cognitive Assessment for evaluating the cognitive impairment in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 65:64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.05.011

Zeng Q, Dong X, Ruan C, Hu B, Zhou B, Xue Y et al (2017) Cognitive impairment in Chinese IIDDs revealed by MoCA and P300. Mult Scler Relat Disord 16:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2017.05.006

Potocnik J, Ovcar Stante K, Rakusa M (2020) The validity of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for the screening of vascular cognitive impairment after ischemic stroke. Acta Neurol Belg 120:681–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-020-01330-5

Abzhandadze T, Rafsten L, Lundgren Nilsson Å, Palstam A, Sunnerhagen KS (2019) Very early MoCA can predict functional dependence at 3 months after stroke: a longitudinal, cohort study. Front Neurol 10:1051. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01051

Zhou L, Wang Y, Qiao J, Wang QM, Luo X (2020) Acupuncture for improving cognitive impairment after stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Psychol 11:549265. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.549265

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I et al (2005) The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 53:695–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

Yao G, Li J, Liu S, Wang J, Cao X, Li X et al (2020) Alterations of functional connectivity in stroke patients with basal ganglia damage and cognitive impairment. Front Neurol 11:980. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00980

Zuo LJ, Li ZX, Zhu RY, Chen YJ, Dong Y, Wang YL et al (2018) The relationship between cerebral white matter integrity and cognitive function in mild stroke with basal ganglia region infarcts. Sci Rep 8:8422. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26316-5

Wu R, Feng C, Zhao Y, Jin AP, Fang M, Liu X (2014) A meta-analysis of association between cerebral microbleeds and cognitive impairment. Med Sci Monit 20:2189–2198. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.891004

Bieńkiewicz MM, Brandi ML, Hughes C, Voitl A, Hermsdörfer J (2015) The complexity of the relationship between neuropsychological deficits and impairment in everyday tasks after stroke. Brain Behav 5:e00371. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.371

Biernaskie J, Chernenko G, Corbett D (2004) Efficacy of rehabilitative experience declines with time after focal ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci 24:1245–1254. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3834-03.2004

Fletcher PC, Shallice T, Dolan RJ (1998) The functional roles of prefrontal cortex in episodic memory. I. Encoding. Brain 121:1239–1248. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/121.7.1239

Cummings JL (1993) Frontal-subcortical circuits and human behavior. Arch Neurol 50:873–880. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1993.00540080076020

Alexander GE, Crutcher MD, DeLong MR (1990) Basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuits: parallel substrates for motor, oculomotor, “prefrontal” and “limbic” functions. Prog Brain Res 85:119–146

Liao Z, Dang C, Li M, Bu Y, Han R, Jiang W (2019) Microstructural damage of normal-appearing white matter in subcortical ischemic vascular dementia is associated with Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores. J Int Med Res 47:5723–5731. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060519863520

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their family members for supporting this study.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the Science and Technology Platform Construction Project of Fujian Science and Technology Department (#2015Y2001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (ethics review number 2017-KL017-02).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patients prior to enrollment.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, B., Wei, D. & Pan, L. Montreal Cognitive Assessment of cognitive dysfunction after basal ganglia stroke. Acta Neurol Belg 122, 881–884 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-022-01967-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-022-01967-4