Abstract

When COVID-19 devastated older-adult organizations (long-term care homes and retirement homes), most public attention was directed toward the older-adult residents rather than their service providers. This was especially true in the case of personal support workers, some of whom are over the age of 55, putting them in two separate categories in the COVID-19 settings: (1) a vulnerable and marginalized group who are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19; and (2) essential healthcare workers. Since the current disaster-driven research, practice, and policy have primarily focused on generalized assumptions that older-adults are a vulnerable, passive, and dependent group rather than recognizing their diversity, expertise, assets, and experiences, this study aimed to identify their contributions from the perspective of older-adult personal support worker (OAPSW). This qualitative study conducted in-depth interviews, inviting 15 OAPSWs from the Greater Toronto Area, Canada. This study uncovered the OAPSWs’ contribution at three levels: individual (enhancing physical health, mental health, and overall well-being), work (improving working environment and service and supporting co-workers), and family (protecting their nuclear and extended families). The outcomes inform the older-adult research, practice, policy, public discourse, and education by enhancing the appreciation of older-adults’ diverse strengths and promoting their engagement and contributions in disaster settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

“If I do not go to work, they will die!” This was the major motivation of one older-adult personal support worker (OAPSW) from the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), Canada, who chose to ignore her own risk to continually provide essential healthcare service for residents in long-term care facilities, during the height of the first two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. When COVID-19 devastated older-adult organizations (long-term care facilities, nursing home and group homes), most public attention was driven toward the adult residents rather than these residents’ service providers, especially the personal support workers, who provide hands-on assistance to support older-adults and/or people with (dis)Abilities in their own homes or in institutions (Kelly and Bourgeault 2015). Unlike the healthcare professionals in traditional healthcare settings (for example, hospitals, emergency rooms, clinics) whose contributions have been widely recognized worldwide, personal support workers bear the same level of health risk (Hapsari et al. 2022) but their contributions have not been widely recognized. Other factors, such as precarious and dangerous settings, violence, low hourly rate, limited employment benefits, and unregular working hours, however, increased their vulnerabilities and their coping capacities during the global public health emergency (Allison et al. 2020).

Research shows that older adults (55 years and above) are disproportionately affected by extreme events (for example, wildfires, heatwaves, and pandemics) (Aldrich and Benson 2008). COVID-19 data have confirmed that older adults are one of the most vulnerable groups (World Health Organization 2023). Regardless of these risks, numerous older-adult physicians, nurses, and other healthcare workers were fighting on the frontline during the pandemic, helping to maintain the regular operation of our society (Lieberman 2021). Older-adult personal support workers are among these frontline professionals, featuring two positions: bearing a higher individual health risk from COVID-19 due to their age and working in a high-risk occupational environment. Furthermore, these OAPSWs have their own families (nuclear families) and extended families (the families of their parents and their children), with both their individual and occupational health effecting their public (at the work level) and private (at the family level) responsibilities. This individual-family-work triangulation forms a critical approach to comprehensively examine how these OAPSWs manage their health risks, while performing their public and private responsibilities. This became the aim of this study.

2 Older-Adult Personal Support Workers and COVID-19

Drawing on previous literature, this section elaborates on the two critical components associated with OAPSWs in disaster settings in general, and also in the global context of COVID-19, in particular. The identified research deficits will lead to the research question of this study.

2.1 Older Adults: Vulnerable But Resilient

Generally, older adults have been labeled as a vulnerable group in disaster settings, bearing higher risks of disaster-driven suffering and/or mortality due to their reduced cognitive capacity, physical functioning, mental health, and overall well-being (Aldrich and Benson 2008). This constraint of public discourse marginalizes them and causes some of them to internalize a sense of worthlessness (Brooke and Jackson 2020). However, previous studies have identified evidence-based outcomes to confirm that older adults are vulnerable but resilient (Barusch 2011). For instance, Hou and Wu’s (2020) study regarding the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake in China illustrated that although older adults were unable to participate in labor-intensive tasks during the emergency response stage (for example, search and rescue), their community-based social networks enabled them to swiftly coordinate residents to conduct self-rescue before the external emergency teams arrived. The older adults’ long-term place-making experience put them in positions to lead their community-based reconstruction by identifying the best (safest) locations, construction methods, and materials to build new residential and other structures (Wu 2020).

Although older-adults’ contributions at the grassroots level have been widely recognized, their life-long experience, knowledge, skills, and expertise have not been fully engaged at the decision-making level. Sinha et al. (2020) point out that older people tend to be overlooked at the legislative and policy levels. This type of disregard reduces their engagement and contributions, increasing the sense of worthlessness, but more importantly, the lack of older-adults’ direct input produced some non-elder-friendly plans, policies, and regulations, resulting in their special needs not being met. Sometimes this negligence can result in tragedies, such as injuries and unnecessary deaths of older-adults during and after disasters.

Focusing on COVID-19, some studies continued the same trajectory (Vervaecke and Meisner 2021), by portraying them in an over-simplified fashion, “as a monolithic group of frails, helpless and vulnerable individuals” (Ng and Indran 2022, p. 64). Their reduced health status required extra protection from social isolation, which triggers their sense of loneliness (Brooke and Jackson 2020). However, Moye (2022) found that older adults’ mental health was less likely to be negatively impacted than the younger generation. Their lifelong experiences have equipped them with a certain level of coping capacity (for example, adapting their daily routine and creating more socializing activities) to support their mental health (Solly and Wells 2020).

On the other hand, older-adult healthcare professionals’ contributions have been widely recognized during COVID-19. For instance, there were retired physicians and nurses who returned to the frontline to help healthcare organizations (hospitals, emergency rooms, and clinics) deal with the public health emergency (Lieberman 2021). Out of healthcare, older-adult professionals also supported the regular operation of essential societal functions, such as transportation, supply chain, critical infrastructure, and emergency shelters (d’Entremont 2021; Wu et al. 2022). Although personal support workers belong to this essential worker group, there has been limited research focused on OAPSWs.

Although long-term care facilities (LTC) worldwide were dramatically devastated by COVID-19, most attention was focused on the mortality of LTC residents, with little attention given to these facilities’ healthcare professional teams (Slick and Wu 2022). This directly resulted in the fact that the confirmed COVID-19 cases documented among healthcare professional teams in LTC are the second highest among all the healthcare occupation categories (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2021). Within the LTC healthcare professional team, personal support workers have not received comparable attention as their peers from the general public. Furthermore, a certain number of them are only being offered part-time positions with a comparatively lower hourly rate and might not have employment benefits (for example, sick leaves, health insurance, and other health service benefits) (Kelly and Bourgeault 2015), COVID-19 related challenges (for example, short of personal protective equipment and short of staff) increased their workload and exposed them to higher potential risk of infection (Pinto et al. 2022), and the age variable worsens their already vulnerable status (Langmann 2023). However, there is a paucity of literature that focuses on the OAPSWs during the pandemic.

2.2 Older-Adult Personal Support Workers in the Individual-Family-Work Triangulation

COVID-19 presented fundamental challenges among healthcare professionals themselves, their families, and their occupational performance (Adams and Wu 2020). The interconnected characteristics among these three domains form an individual-work-family triangulation, enabling the further examination of diverse COVID-19 impacts and identification of the OAPSWs’ unique contributions to their public responsibilities during this health emergency. At the individual level, COVID-19 threatened everyone’s health and well-being through occupational exposure. Many of them were infected at the initial stage due to a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) supply, related knowledge, training, and prevention skills (Nguyen et al. 2020). Their physical health in all scenarios was directly associated with their occupational and family obligations, affecting their mental health (United Nations 2020). Older-adult healthcare staff had more physical risks than their younger peers. The OAPSWs experienced all of these challenges.

During the initial stage of COVID-19, the global challenge regarding the shortage of PPE prevented health care professionals from effectively protecting themselves in workplace settings. Although most personal support workers preferred to follow the PPE guidelines (King et al. 2023), they received inconsistent guidance and unclear PPE usage instruction, experienced physical discomfort when delivering care, and had difficulty communicating with service users and co-workers. All this caused unfavorable impacts on their occupational performance and mental health (Hoernke et al. 2021). High-risk workplace environments and lower benefits propelled some of them to temporarily leave their employment and even quit the healthcare industry (White et al. 2021). The staff shortage in the healthcare sector resulted in many staff being overworked (White et al. 2021), and experiencing physical and mental burnout (Basa 2022).

The society-wide economic impact of COVID-19 threatened income security (Hapsari et al. 2022). Some service users canceled their in-person services in order to avoid infections, and some clients could no longer afford the service due to their individual financial hardship (Pinto et al. 2022). That caused many personal support workers losing their income, which added an extra financial burden on their already stressed mental health (Pappa et al. 2020). Many of them were reluctant to seek emotional support from their peers because they did not want to burden others (Nizzer et al. 2022), which further jeopardized their health and well-being. At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, OAPSWs who had worked for over 10 years were equipped with some experiences and skills from previous pandemics, especially Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). Information about how these OAPSWs utilized their previous experience and skills to protect themselves and support their peers in the work settings remains sparse.

During pandemics or other public health emergencies, “it is morally permissible for healthcare workers to abstain from work when their duty to treat is outweighed by the combined risks and burdens of that work” (McConnell 2020, p. 363). Healthcare workers’ family obligations feature at both nuclear and extended family levels. In order to better fulfill their public responsibilities, many healthcare professionals decided to sacrifice time with their families (Helou et al. 2022). For example, they followed the recommendations on infection control and stopped being in constant touch with their families. They showed care by running family errands, sending cards, letters, and care packages, and visiting in person by maintaining social distance (Bender et al. 2021). In some cases, some older staff had to stop seeing their grandchildren (Brophy et al. 2021). For those who lived with their elderly parents, a social distance at home had to be maintained (Doolittle et al. 2020). These types of contributions, in turn, enabled healthcare professionals to balance their public and private responsibilities and support their mental health. However, these contributions have not been examined among OAPSWs.

In summary, in disaster settings in general, previous studies confirm that many older-adults experience age-related vulnerabilities, but their life-related expertise enabled them to contribute to diverse disaster management efforts. In the COVID-19 context, in particular, OAPSWs have experienced challenges in balancing their personal health and well-being, as well as work and family obligations. Integrating the general and particular scenarios generates the research question: How did OAPSWs contribute to their individual-work-family triangulations during the COVID-19 pandemic?

3 Research Methods

This qualitative study applied a phenomenological approach to explore how the OAPSWs overcame their challenges when they provided direct care during the first two COVID-19 waves in GTA, Ontario, Canada (Wave 1: 1 March to 31 August 2020; and Wave 2: 1 September 2020 to 15 February 2021) (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2021). The GTA was considered one of the epicenters of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada (Xia et al. 2022), where the LTC facilities featured the second highest resident and staff-specific COVID-19 cases after Quebec (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2021). These characteristics of both general geographic surroundings and their employment environment jointly increased the potential risk for OAPSWs, building a valuable research background to deeply explain how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the individual-work-family triangulation of these essential workers. This study was approved by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Ethics Board at Dalhousie University (certificate number #: 2022-5955), Canada.

3.1 Research Participants

Older-adult personal support workers are usually employed in two types of employment settings: (1) LTC homes, where the majority of the older-adult residents have chronic, complex health issues, and where the healthcare services are available 24 hours a day, 7 days per week. The service users in LTC homes are referred to as residents; and (2) retirement homes, also known as assisted living in community settings, where OAPSWs provide service (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2021). The service users in retirement homes are also referred to as residents. This study recruited 15 OAPSWs from both occupational arrangements: 7 OAPSWs were recruited from LTC homes (referred to as L-OAPSW) and 8 OAPSWs came from retirement homes (referred to as R-OAPSW) through a snowball sampling strategy. The seed samples were identified from both authors’ professional connections and networks with LTC homes and retirement homes. Then, these seed people helped distribute the research invitation through their professional connections. Interested participants contacted the two authors directly. The first 15 eligible participants were invited for interview. Table 1 shows the participants’ demographic composition.

3.2 Data Collection

The 15 OAPSWs were invited for individual, in-depth, and semistructured interviews supported by Microsoft Teams. Each virtual interview, ranging from half an hour to one hour, was conducted during March 2022. The two authors interviewed L-OAPSWs and R-OAPSWs respectively. As shown in the table, all the participants are immigrants. Hence, the two authors used the participants’ preferred languages (Cantonese, English, and Mandarin) to conduct the interview. The open-ended interview questions were developed based on four main categories: (1) the OAPSWs’ basic demographic information; (2) their individual experience; (3) their work performance and experience during the first two waves of COVID-19; and (4) family-specific impacts. The semistructured interview allowed the interviewers to swiftly adjust the sequence of questions according to the interviewee’s responses, and this encouraged the interviewees to elaborate more on different topics (Young et al. 2018). The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, translated into English, and analyzed by qualitative data analysis software NVivo 12. The second author proofread all the interview transcripts priori to data analysis.

3.3 Data Analysis

The two authors applied a content analysis approach to analyze the interview transcripts independently and collaboratively (Palinkas et al. 2015). Utilizing deductive and inductive strategies, the two authors, with expertise in public health emergency management and social work, respectively, developed codes independently on all the interview transcripts. They discussed their codes and collaboratively grouped different codes into subthemes. This strategy ensured inter-rater reliability when the two researchers coded the same data (Hemmler et al. 2020).

Specifically, following the interview flow, the first round of analysis, deductive (top-down) analysis, examined the logical and substantiated ties with predetermined codes associated with various COVID-19-related factors that had direct and indirect impacts on OAPSWs’ individual-family-work triangulation experience (for example, individual health, occupational health, and family well-being) (Hemmler et al. 2020). Under these predetermined codes, the two authors further developed sub-codes to contribute to a nuanced understanding of COVID-19-specific impacts. These codes were grouped into different subthemes and then merged into the following three primary categories: personal struggles, challenges at work, and family situations. Then, the two authors discussed the themes and subthemes and identified the connections between the age variable and the participants’ individual-work-family-specific challenges and their solutions, which clearly showed these OAPSWs’ unique contributions.

In the second round of analysis, the researchers used the inductive (bottom-up) approach, which discovered emerging themes based on the data without preconceived categories (Hemmler et al. 2020), to review the OAPSWs’ experience. This round of data analysis particularly focused on OAPSWs’ contributions around their private and public responsibilities. New subthemes were developed to support the comprehension of OAPSWs’ unique efforts at the individual, family, and workplace levels.

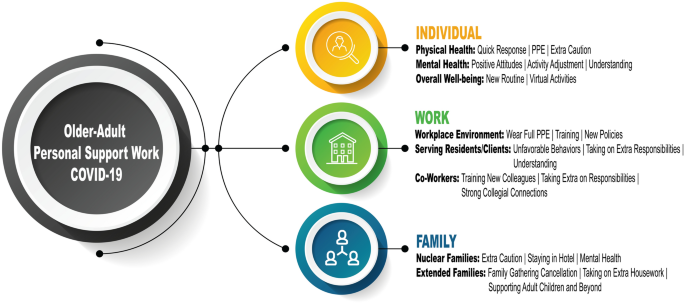

The two authors discussed the themes, subthemes, and codes from these two rounds of data analysis. Combining the deductive and inductive outcomes guided the authors to have an in-depth understanding of the participants’ experiences (Saldaña 2009) and design the final data analysis structure as shown in Fig. 1. The data analysis structure was built on three thematic areas—individual, work, and family—which is aligned with the core platform of this research: individual-family-work triangulation. Under each thematic area, two or three subthemes were identified, supporting by different codes.

4 Findings

As shown in Fig. 1, this section provides detailed information to elaborate on the OAPSWs’ unique contributions within each of their individual-workplace-family triangulations. In each category, interview quotations from both L-OAPSW and R-OAPSW participants are presented in order to comprehensively portray the OAPSWs’ contributions.

4.1 At the Individual Level

Current studies statistically shown that older adults’ physical health, mental health, and overall well-being were disproportionately affected by COVID-19 (Brooke and Jackson 2020). Although the OAPSWs fall into two categories (age and occupational health) of high risks of contracting COVID-19, they continued to support the people around them. This section focuses on OAPSWs’ contributions in the areas of these three components.

4.1.1 Physical Health: Protect Themselves and Protect Others

The physical health risk was the first consideration for everyone in the COVID-19 setting. The participants explained their physical health considerations, as shown in what the following two participants said. One participant, a L-OAPSW, shared her reactions to the news regarding the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China.

You might know about the SARS outbreak in Toronto in 2003, almost 18 years ago. SARS put me on high alert. When I heard about the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, I knew how serious it would be. I am the breadwinner of my family, and I cannot get sick. I must take good care of myself so that I can take care of my family and my clients. I was trying to buy masks and sanitizer, but at that point, they were out of stock in almost every store. I made cloth masks and shared them [with my family, friends, and co-workers].

One R-OAPSW participant highlighted her actions of using PPE.

I know I have a high risk of getting infected due to my age. I doubled my masks every day when I heard the confirmed cases were reported in my community. I do not care about other people’s thoughts about wearing a mask. I am cautious, and do not want to get sick because all my clients are high-risk people. If I got sick, no one would help them.

These two participants expressed their consideration toward individual physical health, not only for themselves but also for their family and their clients. This consideration was reflected in their willingness to reduce the burden on others and better fulfill their private (family) and public (work) responsibilities.

4.1.2 Mental Health: Keeping Positive and Showing Positivity to Others

All the participants indicated that their mental health had been negatively affected by the pandemic. They also understood the long-term impacts of mental health and developed different adaptive strategies. One R-OAPSW shared that she managed her stress by modifying her activity.

[Before the pandemic], I went to gym almost every day. I felt so good because [workout] took the stress away. But now I can’t do that because I am afraid if I get infected, my colleagues, my clients, and my family would be at risk. When I felt stressed, I would play with my doggie and take him for a walk.

The risk of the community spread of the virus made some clients reduce or even cancel their regular service. This had economic impacts on the participants and triggered their anxiety and stress. The following two R-OAPSWs illustrated that focusing on their public responsibilities helped them deal with adverse mental health outcomes and enabled them to continually serve their clients. One R-OAPSW illustrated his strategies of applying positive thinking to deal with negative attitudes toward the mental and economic impacts.

I am workaholic. I feel uncomfortable about not working. Everyone is afraid, but there is someone who has to work. Otherwise, who can take care of the clients [older adults]? Although my hours have decreased, the market will resume because of the large aging population.

Another R-OAPSW shared that when her mood was low, she always put her clients first, which helped her deal with some negative thoughts.

I heard a lot of my co-workers quit their jobs during COVID-19. Although I am only one of them, if I quit my job or am unable to work, they might need to look for a replacement.

Unlike R-OAPSWs, the mental health-related issues of L-OAPSWs were primarily triggered by their work-related consideration. One L-OAPSW participant hid her sadness and worries and always showed joyous smiles to others.

I am afraid of checking my cell phone because of widespread bad news, such as there was a breakout in LTCs, how many older adults got infected, and how many died. I am so worried that it will happen in my organization. I lived in the hotel alone for two weeks. I felt hopeless, but I told myself that I needed to be strong because the residents needed me, my co-workers needed me, my practicum students needed me, and my family needed me. Although we wore masks, I always smiled at them and said, “Everything will be fine.”

These participants identified different coping strategies to reduce the negative impacts on their mental health. These coping strategies were upheld by their feelings of commitment and responsibility toward their clients, colleagues, and family. Their effort in maintaining mental well-being confirms their contributions to the entire society.

4.1.3 Overall Well-Being: Adjusted Social Activities

COVID-19 public health mitigations reshaped people’s social life. All participants illustrated that the changes in their regular social activities impacted their overall well-being. One R-OAPSW used to be an active person, but COVID-19 caused all her regular social activities to be canceled. She developed new ways to help herself and her friends.

I used to join line-dance classes and singing classes weekly and frequently have parties with my friends. During the pandemic, all these activities were canceled, and we had to stay home. I felt depressed and bored, but I think I must change. So I asked my friends to move [our activities] online. We have virtual meetings, parties, and singing together. More and more of my friends joined these [activities], and they felt better as well.

One L-OAPSW used virtual yoga to encourage her friends and family to keep active so that their well-being was supported.

I love yoga, especially hot yoga. I usually went to the morning yoga class after my night shift. [During the closure of the yoga studio], I followed the tutorial on YouTube to do that at home. I also introduced the online yoga class to my friends. I know they felt depressed, and yoga could help. We did the online yoga together, recorded it, and shared the recordings with other friends and family. Of course, more people joined us.

These two participants became proactive to stay grounded by adjusting their usual activities. The individual experiences enabled them to understand that people around them experienced the same challenges. Hence, they shared their strategies to support others.

4.2 At the Work Level

Health-specific considerations propelled many personal support workers to quit, increasing a labor shortage in this field. All the participants stayed at their positions throughout the first 2 years of COVID-19. COVID-19 caused different challenges in their working environments that forced these OAPSWs to re-adjust themselves to better cope with the new normal. This section focuses on three components of the workplace: the workplace environment, the residents or clients, and the staff.

4.2.1 Workplace Environment: Reducing the Spread of Coronavirus

With the unfolding of COVID-19, all the participants confirmed that their agencies implemented new guidelines to protect clients/residents and staff. These OAPSWs took extra care to avoid the spread of the virus at work. In the community settings, R-OAPSWs were not required to wear full PPE when providing service in clients’ homes. One R-OAPSW explained that he always took extra steps to protect his clients and their families.

When I entered my client’s home, I immediately did a screening by observing if [my client] had any symptoms. Then I checked their temperature. If [my client] had a fever or any flu symptoms, I would not provide service and reported the situation to my agency immediately. It is essential to avoid getting infected by the clients and to ensure the safety of all my other clients. I encourage my other co-workers to do the same, protecting themselves and others. I know the young people do not care, but I do; it is my duty.

An R-OAPSW working in a group home for people with developmental (dis)Abilities shared that because the residents did not understand the situation, she had to protect the residents and herself.

When you help them [residents] put on masks, they immediately take them away. Other PSWs might not care about that. So lucky they [residents] had me. I made a distance for each resident, and I wore the [facial] shield when I was in contact with them.

Another R-OAPSW appreciated the COVID-19 training her agency provided. She advocated this type of training for her co-workers to protect themselves, their clients, and others.

My company offered paid training in English, Cantonese, and Mandarin for all the staff. The latest training was on how to observe a client when we provide service. We learned how to determine the wellness of a client by observing their behaviors and speech. All my co-workers should receive this training.

In the long-term care facilities, extra mitigation strategies were applied, such as COVID-19 testing of residents and staff and restricting to essential visitors only (Slick and Wu 2022). One L-OAPSW mentioned that although the process was exhausting, it was worth it.

COVID-19 put everyone in my agency on high alert. Although there were no confirmed cases [in my workplace], I always encouraged everyone to follow the requirements. I understand that it is not easy to serve residents while wearing PPE. The guidelines have increased extra hours [for us to prepare before and after serving the residents], but we have to follow the guidelines to complete all the screening and cleaning steps because any oversight would cause huge mistakes.

Four OAPSWs demonstrated their significant role in contributing to the prevention of the spread of the virus while providing essential care to clients. They highlighted that it was their responsibility to protect themselves so that they were able to protect and serve their clients. As the first OAPSW mentioned, he also educated other OAPSWs to feel obligated to follow the COVID-19 precaution practice.

4.2.2 Serving Residents/Clients: Managing Clients’ Challenging Behaviors and Supporting Their Mental Health

Compared with the L-OAPSWs, most of the R-OAPSW participants indicated that they were frequently mistreated by their clients and their families before the pandemic. COVID-19 increased these unfavorable behaviors. One R-OAPSW took on extra responsibilities to provide activities to assist residents in managing their mental health.

The residents used to go out to participate in some day programs every day. But they couldn’t go anymore [during COVID-19]. Their behaviors have changed a lot. I explained the situation, but they still did not understand and became more agitated, more anxious, and sometimes, cannot control their emotions. Even though they have virtual [mental health] programs, it’s not enough for them to take off their stress. It is not my job, but I explained to them again and again, talked with them, and tried to have a little fun with them to make them feel at ease.

One L-OAPSW explained her willingness to take on extra responsibilities.

When LTCs did not allow family visits, most of the residents felt very lonely and became very upset. I had to be careful when I did the screening. Some residents got upset when I asked them questions about their symptoms. I also kept quiet. After completing my work, I always stayed a little bit longer and talked with them. I always told them that the pandemic would be over very soon, and they could see their families soon. There was a resident who passed away during the lockdown. My co-worker and I acted as her family to help her clean and dress up [for funeral].

These OAPSWs illustrated their willingness to take on extra work to deal with clients’ unfavorable behaviors and support their mental health. Other participants also showed their understanding of their clients/residents’ situation and used their knowledge and skills to provide more support.

4.2.3 Co-workers: Providing Mutual Support

Working in the same agency, the L-OAPSWs usually have fixed team members. During COVID-19, PSWs in the same team could work in the same zone or on the same floor. They supported one another, and COVID-19 strengthened their connections. One L-OAPSW shared her experience of leading her team and working with a new team member during COVID-19.

We have been collaborating in a team very well for a long time. Sometimes, just an eye expression from my co-worker, we know what we should do. [This was very important] because we all wore PPE and could only see the eye’s expression. Although we had extra work during COVID-19, everyone just completed the work with no complaints at all. I supervised a new colleague during COVID-19, and I requested other team members to be more patient with [the new colleague]. We went through the most challenging period together, and no one on my floor got COVID-19.

Another L-OAPSW considered that all her team members were overwhelmed, so she did not take her non-COVID-19-related sick leave.

I was planning to take a sick leave due to my back pain, but COVID-19 disrupted the plan. You might know that a lot of PSWs quit their job and my husband asked me to stay at home too. But I decided not to do that because it was tough to find someone to take my position. Otherwise, all my work would be shared by my co-workers, who were overwhelmed as well. Even if a new person could be hired, the new person needs a while to become familiar with all the logistics, so that my co-workers can collaborate well. We were a team, and I could not be so selfish. My co-workers did the same as well.

Another L-OAPSW shared her hand-made PPE with her co-workers and their families.

I had a sewing machine. I made masks, hats, and gowns and shared them with my co-workers. All my co-workers were very proud of me. You knew those things were sold out almost everywhere. They [co-workers] also shared the extra masks, hats, and gowns I made with other PSWs in other long-term care facilities because we were colleagues. When we heard that [some LTCs’] situations were horrible, we all donated our PPE to them.

Compared to the L-OAPSWs, the R-OAPSWs might not have powerful collegial connections. However, they collaborated to advocate for better PPE and showed empathy among them. One R-OAPSW shared that they requested enough and better PPE, in order for all the staff to have access to enough and better equipment.

[At the beginning of the pandemic], there was a shortage of PPE [almost everywhere]. We only received one level-one mask per day, no extra to replace, and the level-one mask does not provide enough protection [when we were in direct contact with clients]. My co-workers teamed in different groups. Each group made complaints to the agency and asked for better PPE. After several complaints, we started to receive more and better PPE.

The OAPSWs faced extra challenges at work during the pandemic but their contributions improved the working environment, provided extra support to their clients/residents, and helped their co-workers in their agencies and beyond.

4.3 At the Family Level

Some OAPSWs’ children live in their own homes with their own families. Some OAPSWs still have children living with them. Their occupational responsibilities directly affected these OAPSWs’ nuclear families and indirectly influenced their extended families.

4.3.1 Committed to Protecting Their Nuclear Families

During the pandemic, most healthcare professionals made extra efforts to protect their nuclear families from contracting the virus after finishing their duties. The following three examples show these OAPSWs’ commitment to support their nuclear families. One R-OAPSW shared that he washed himself before seeing his family after he returned home from work.

When I got home [every afternoon], I took off all the dirty clothes in the laundry room immediately, which was located beside the garage, took a shower, and put on new clothes. After that, I had dinner with my family.

Another L-OAPSW explained that she stayed in a hotel in order to protect her family.

I stayed in the hotel for two weeks since a confirmed case was identified in my agency. I Facetimed with them [my family] every evening after work. It was tough for me because you lived so close, but you could not have dinner with them. But I know it was the best choice I made.

The OAPSWs’ individual and professional experience prompted them to pay extra attention to their family’s mental health and overall well-being. One L-OAPSW explained that:

My daughter’s graduation trip was canceled, she could only socialize with her friends online, and her new job was pending. I realized that these took a hefty toll on her mental health. Hence, on my days off, I always walked with her in our community park. When the travel ban was lifted, we planned a trip immediately.

4.3.2 Supporting Extended Families

Some OAPSWs supported their adult children pre-COVID-19 by taking care of their grandchildren; spending time with their family always would be the most enjoyable time during this daily routine. COVID-19 forced the cancellation of these family times and OAPSWs also took on extra responsibilities to support their extended families. One R-OAPSW indicated that although her antigen test showed negative and she did not have symptoms, she still canceled her family gatherings.

I took care of my grandsons once a week [before COVID-19]. That became my big concern because they are too young to be vaccinated. I did the antigen test, and I did not have any symptoms, but there was still a possibility that I might bring COVID-19 to them. At that time, I was so upset, but I had no choice, and I needed to cancel their visiting to protect them.

One L-OAPSW described her interventions to help her extended family:

All my children have their own families, and we live very close. They all worked from home [during COVID-19]. Since I had to go outside to work every night, I asked them what they needed so that I could prepare the next day. Every morning after work, I purchased groceries and dropped them off at their houses. COVID-19 increased our workload, and I always had colleagues get sick, and I had to cover their responsibilities. I was exhausted after work since COVID-19. But I still did all these things so that my family did not have to go out.

The support given to their extended families always moves beyond their own family circle. The following R-OAPSW explained his reasons for maintaining his employment during the COVID-19 pandemic so that he would help other people in need to benefit from the government’s social benefits.

My wife suggested that I should quit my job and take the EI [employment insurance] or CERB [Canada Emergency Response Benefit]. We have some savings, so we would be OK. So many people, like my children, lost their jobs. They might not have enough experience, and they could not find a new one soon. Although many of my clients canceled their service, I was lucky, and I still had a job to survive. So I decided to work and give the opportunities [EI or CERB] to my children and others.

5 Discussion

Based on the findings of the OAPSWs’ contributions, this section further examines the OAPSWs’ agency associated with the individual-work-family triangulation, contributing to existing literature.

5.1 Empowering Older-Adult Personal Support Workers’ Agency

The interview data confirmed that OAPSWs experienced “complex, challenging, and evolving conditions” during COVID-19 (White et al. 2021, p. 202) but also highlighted the various COVID-19-specific impacts on OAPSWs through their individual-work-family triangulations. Specifically, this study demonstrated their vulnerable status associated with their age and professional (essential healthcare workers in high-risk workplace settings) variables increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, their life-based experiences enable them to manage the diverse vulnerabilities (Solly and Wells 2020) and workplace challenges and contribute to the prevention and mitigation of public health emergencies. At the individual level, they made extra efforts to prevent from being infected themselves, by adjusting their regular de-infection practice and their personal activities. For example, one interviewee mentioned that her SARS experience enabled her to swiftly mobilize more protection strategies. The experience not only maintained their physical, mental, and overall well-being but also propelled them to educate their younger colleagues, the residents, and clients at the work level. Their extra efforts created a safer and more supportive working environment. At the family level, their extra efforts developed multiple approaches that enabled them to fulfill their private responsibilities (for example, virtual visiting and grocery shopping) towards their nuclear and extended families (Bender et al. 2021).

These OAPSWs’ life-long experiences played an essential role in developing their extra, practice-oriented efforts. Their experiences enabled them to comprehensively consider the vulnerabilities of their residents/clients, their families, and the general public affected by COVID-19. For instance, their consideration regarding the COVID-19-specific mental health consequences for their colleagues, residents/clients, and families, and their decision to maintain their essential duties during the peak period to reduce the workload of their colleagues and to provide the opportunities for other people to receive unemployment benefits illustrated their extended contributions beyond their individual-work-family triangulation, bringing about positive changes in society.

5.2 Supporting Older-Adult Personal Support Workers

This study confirmed the current literature’s argument that older adults are vulnerable but resilient (Hou and Wu 2020). They are community-based assets. Leveraging their strengths, experiences, networks, and other expertise fundamentally promotes the community-based disaster management efforts. These types of contributions discussed during the interviews only partially demonstrated the OAPSWs’ heroic contributions made during the pandemic. The stereotype regarding the aging population produced by the public discourse have been challenged by the OAPSWs’ active engagement and tremendous contributions during the pandemic. Their involvement and contributions reflect the urgent need to reframe the passive depiction of aging, and reconsider these people as valuable assets. The limited studies focusing on older adults’ selfless and valuable engagement in disaster settings call for further research to uncover more about the agency of older adults.

Understanding the OAPSWs’ agency indicates that further support for this group is needed in order to promote their contributions. For the healthcare professionals in general, their friends, neighbors, and other community members took care of these frontliners (for example, preparing meals and making care packages for them) and their families (for example, taking care of their children and elderly parents) during COVID-19 so that these frontliners could completely devote themselves to fulfilling their essential roles. All of this support could be offered to OAPSWs as well. The OAPSWs should be recognized as essential workers so that related healthcare resources (for example, PPE and training) could be properly prioritized, fundamentally reducing the barriers so that they will be able to more safely work on the frontline. In the work environment, having older-adult OAPSWs to lead briefing would enable them to share their experience and to provide leadership in handling the challenging time. The OAPSWs should also be assigned leadership roles at the organizational level, so that they could provide frequent peer support (for example, wellness check-in and consulting) to their co-workers, providing these professionals with high-quality services. Receiving family understanding and support is vital in order for OAPSWs to improve their professional performance. Everyone on the Earth is connected to varying degrees. All these multi-aspects of support will augment the contributions of the older adults.

6 Limitations and Future Research

The discussion of this study’s limitations will support knowledge mobilization within Canada and internationally. Although the findings are promising, it is vital to note the following limitations. First, all participants are self-identified immigrants from East Asia or Southeast Asia (China, Hong Kong SAR of China, the Philippines, and Korea). Research has confirmed that although these immigrants have been living in Canada for a long time, their social engagement still primarily focuses on the Asian communities and Asian cultures they come from (Jia and Krettenauer 2022). For example, when providing the language choices for the interviewees, all the interviewees whose first language is non-English chose their mother tongue. The snowball sampling approach also confirmed this implication because the interviewees shared the project information within their Asian communities. Furthermore, collectivism predominates among countries in East Asia and Southeast Asia. This cultural background makes them likely to sacrifice themselves to support others. However, the cultural background has not fully engaged in the data analysis process of this project, indicating a future research area to examine the interconnections between the OAPSWs’ contributions and their cultural backgrounds. Future studies should investigate OAPSWs from other ethnic groups to further explore the differences within various cultures and develop appropriate strategies to promote OAPSWs’ strengths.

Although gender information was collected, this study mainly focused on the experience of OAPSWs in general, rather than deeply engaging gender factor into data analysis. Gender, reflecting the OAPSWs’ social roles, significantly shapes OAPSWs’ private and public responsibilities and impacts their contributions in the disaster and emergency management field (Drolet et al. 2015; Hou and Wu 2020; Wu et al. 2021). This indicates a potential research area for applying gender lens to comprehensively examine the OAPSWs’ contributions.

Moreover, although GTA provides a typical research setting, the provincial public health policies and other governmental interventions, and the structure of LTC differ from other provinces or territories in Canada. Hence, the research outcomes might not be directly mobilized beyond GTA and other Canadian jurisdictions, let alone the international scope. However, in this study, promising practices have been assuredly illustrated by the OAPSWs’ agency, which enables them to continually contribute to our society and this should also be reflected in other geographical areas. Prospective research may engage the OAPSWs from other Canadian jurisdictions and international communities to better understand the similarities and differences among them, and strengthen the knowledge mobilization promise.

7 Conclusion

Utilizing an individual-work-family triangulation approach, this study highlighted the three-level contributions that older-adult personal support workers (OAPSWs) delivered during the emergency response phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the individual level, they bore the potentially high risk of getting infected by the virus, but, nonetheless, supported the people around them. At the workplace level, they took on extra responsibilities to support their co-workers to keep their organizations’ operations providing a high-quality performance. At the family level, they took on extra responsibilities to take care of their family members physically, socially, and emotionally. While enduring age-related physical health risks, OAPSWs’ life-long experience enabled them to swiftly adapt to the COVID-19 setting, protecting themselves, their colleagues, their residents/clients, and their families.

In the global context of COVID-19, the OAPSWs’ contributions associated with their individual-work-family triangulation illustrate their agency in dealing with public health emergencies, and other disasters in general. Furthermore, these findings shed light on older-adult strengths, expertise, and leadership, which promote different disaster management efforts to enhance the individual and collective health and well-being, as well as advance resilience at the individual, work, and family levels. Future research could engage diverse older-adult professionals and explore their demographic information (for example, gender and ethnicity) in order to comprehensively understand their strengths in different settings. These prospective studies would promote the older adults’ continuous engagement and contributions to our society, promoting individual and collective resilience.

References

Adams, R., and H. Wu. 2020. Enhancing our healthcare heroes’ overall well-being: Balancing patient health, personal risk, and family responsibilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Natural Hazards Center Grant Report Series, 316. Boulder, CO: Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/balancing-patient-health-personal-risk-and-family-responsibilities-during-the-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed 1 Apr 2024.

Aldrich, N., and W.F. Benson. 2008. Disaster preparedness and the chronic disease needs of vulnerable older adults. Preventing Chronic Disease 5(1): Article A27.

Allison, T.A., A. Oh, and K.L. Harrison. 2020. Extreme vulnerability of home care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic—A call to action. JAMA Internal Medicine 180(11): 1459–1460.

Barusch, A.S. 2011. Disaster, vulnerability, and older adults: Toward a social work response. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 54(4): 347–350.

Basa, J. 2022. Health care workers in need of mental health support amid pandemic burnout. CTV News, 24 January 2022.

Bender, A.E., K.A. Berg, E.K. Miller, K.E. Evans, and M.R. Holmes. 2021. “Making sure we are all okay”: Healthcare workers’ strategies for emotional connectedness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical Social Work Journal 49: 445–455.

Brooke, J., and D. Jackson. 2020. Older people and COVID-19: Isolation, risk and ageism. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29(13–14): 2044–2046.

Brophy, J.T., M.M. Keith, M. Hurley, and J.E. McArthur. 2021. Sacrificed: Ontario healthcare workers in the time of COVID-19. New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy 30(4): 267–281.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on long-term care in Canada: Focus on the first 6 months. Ottawa, ON: CIHI. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/impact-covid-19-long-term-care-canada-first-6-months-report-en.pdf. Accessed 1 Apr 2024.

d’Entremont, Y. 2021. Researchers launching online survey to learn how pandemic is affecting grocery store workers. Halifax Examiner, 23 December 2021. https://www.halifaxexaminer.ca/featured/researchers-launching-online-survey-to-learn-how-pandemic-is-affecting-grocery-store-workers/. Accessed 1 Apr 2024.

Doolittle, R., E. Anderssen, and L. Perreaux. 2020. In Canada’s coronavirus fight, front-line workers miss their families, fear the worst and hope they’re ready. The Globe and Mail, 4 April 2020.

Drolet, J., M. Alston, L. Dominelli, R. Ersing, G. Mathbor, and H. Wu. 2015. Women rebuilding lives post-disaster: Innovative community practices for building resilience and promoting sustainable development. Gender & Development 23(3): 433–448.

Hapsari, A.P., J.W. Ho, C. Meaney, L. Avery, N. Hassen, A. Jetha, A.M. Lay, and M. Rotondi et al. 2022. The working conditions for personal support workers in the Greater Toronto Area during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods study. Canadian Journal of Public Health 113(6): 817–833.

Helou, M., N.E.I. Osta, and R. Husni. 2022. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers’ families. World Journal of Clinical Cases 10(27): 9964–9966.

Hemmler, V.L., A.W. Kenne, S.D. Langley, C.M. Callahan, E.J. Gubbins, and S. Holder. 2020. Beyond a coefficient: An interactive process for achieving inter-rater consistency in qualitative coding. Qualitative Research 22(2): 194–219.

Hoernke, K., N. Djellouli, L. Andrews, S. Lewis-Jackson, L. Manby, S. Martin, S. Vanderslott, and C. Vindrola-Padros. 2021. Frontline healthcare workers’ experiences with personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: A rapid qualitative appraisal. BMJ Open 11(1): Article e046199.

Hou, C., and H. Wu. 2020. Rescuer, decision-maker, and breadwinner: Women’s predominant leadership across the post-Wenchuan Earthquake efforts in rural areas, Sichuan, China. Safety Science 125: 1–6.

Jia, F., and T. Krettenauer. 2022. Moral identity and acculturation process among Chinese Canadians: Three cultural comparisons. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 88: 125–132.

Kelly, C., and I.L. Bourgeault. 2015. The personal support worker program standard in Ontario: An alternative to self-regulation?. HealthCare Policy 11(2): 20–26.

King, E.C., K.A.P. Zagrodne, S.M. McKay, D.L. Holness, and K.A. Nichol. 2023. Determinants of nurse’s and personal support worker’s adherence to facial protective equipment in a community setting during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada: A pilot study. American Journal of Infection Control 51(5): 490–497.

Langmann, E. 2023. Vulnerability, ageism, and health: Is it helpful to label older adults as a vulnerable group in health care?. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy 26(1): 133–142.

Lieberman, C. 2021. COVID-19: Retired health-care workers answer call to help on front lines. Global News, 19 March 2021.

McConnell, D. 2020. Balancing the duty to treat with the duty to family in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Medical Ethics 46(6): 360–363.

Moye, J. 2022. Mental health in older adults during COVID: Creative approaches and adaptive coping. Clinical Gerontologist 45(1): 1–3.

Ng, R., and N. Indran. 2022. Reframing aging during COVID-19: Familial role-based framing of older adults linked to decreased ageism. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 70(1): 60–66.

Nguyen, L.H., D.A. Drew, M.S. Graham, A.D. Joshi, C.G. Guo, W. Ma, R.S. Mehta, and E. Warner et al. 2020. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet: Public Health 5(9): e475–e483.

Nizzer, S., N. Moreira, S. McKay, and E. King. 2022.Who meets home care workers’ emotional support needs? Toronto, ON: VHA. https://www.vha.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Moreira_WhoMeetsHomeCareWorkersEmotionalSupportNeeds_Abstract_Sept2022.pdf. Accessed 1 Apr 2024.

Palinkas, L.A., S.M. Horwitz, C.A. Green, J.P. Wisdom, N. Duan, and K. Hoagwood. 2015. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services 42: 533–544.

Pappa, S., V. Ntella, T. Giannakas, V.G. Giannakoulis, E. Papoutsi, and P. Katsaounou. 2020. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 88: 901–907.

Pinto, A., A.P. Hapsari, J. Ho, C. Meaney, L. Avery, N. Hassen, A. Jetha, and A. Morgan Lay et al. 2022. Precarious work among personal support workers in the Greater Toronto Area: A respondent-driven sampling study. CMAJ Open 10(2): E527–E538.

Saldaña, J. 2009. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Sinha, S.K., W.R. Spurlock, G.A. Allison, B. Earley, C. Taylor, E. Prendergast, J. Snelling, and J. Carmody et al. 2020. Closing the gaps: Advancing disaster preparedness, response and recovery for older adults. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Red Cross.

Slick, J., and H. Wu. 2022. The need to protect the most vulnerable: The COVID-19 crisis in long-term and residential care in Canada. In Countries in crisis: Collective cognition action and COVID-19, ed. M.L. Rhodes, and L. Comfort, 182–207. New York: Routledge.

Solly, K.N., and Y. Wells. 2020. How well have senior Australians been coping with the COVID-19 pandemic?. Australasian Journal on Ageing 39: 386–388.

United Nation. 2020. Policy brief: COVID-19 and the need for action on mental health. https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-covid-19-and-need-action-mental-health. Accessed 1 Apr 2024.

Vervaecke, D., and B.A. Meisner. 2021. Caremongering and assumptions of need: The spread of compassionate ageism during COVID-19. Gerontologist 61(2): 159–165.

White, E.M., T.F. Wetle, A. Reddy, and R.R. Baier. 2021. Front-line nursing home staff experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 22(1): 199–203.

World Health Organization. 2023. COVID-19: Vulnerable and high-risk groups. https://www.who.int/westernpacific/emergencies/covid-19/information/high-risk-groups#:~:text=If%20you're%20at%20risk,to%20contact%20your%20health%20provider. Accessed 8 Oct 2023.

Wu, H. 2020. Airdropped urban condominiums and stay-behind elders’ overall well-being: 10-year lessons learned from the post-Wenchuan Earthquake rural recovery. Journal of Rural Studies 79: 24–33.

Wu, H., J. Karabanow, and T. Hoddinott. 2022. Building emergency response capacity: Social workers’ engagement in supporting homeless communities during COVID-19 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: Article 12713.

Wu, H., M. Perez-Lugo, C.O. García, F. Gonzalez, and A. Castillo. 2021. Empowered stakeholders: University female students’ leadership during the COVID-19-triggered on-campus evictions in Canada and the United States. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 12(4): 581–592.

Xia, Y., H. Ma, G. Moloney, H.A. Velásquez García, M. Sirski, N.Z. Janjua, D. Vickers, and T. Williamson et al. 2022. Geographic concentration of SARS-CoV-2 cases by social determinants of health in metropolitan areas in Canada: A cross-sectional study. CMAJ 194(6): E195–E204.

Young, J.C., D.C. Rose, H.S. Mumby, F. Benitez-Capistros, C.J. Derrick, T. Finch, C. Garcia, and C. Home et al. 2018. A methodological guide to using and reporting on interviews in conservation science research. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 9: 10–19.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), Insight Development Grants (Award # 430-2021-00352). This research was also undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs Program (Award # CRC-2020-00128).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Yung, M. “If I Do not Go to Work, They Will Die!” Dual Roles of Older-Adult Personal Support Workers’ Contributions During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 15, 226–238 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-024-00553-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-024-00553-x