Abstract

During times of crisis, including pandemics, climate change, and forced migration, much of the discourse in ageing research and intervention centers on the vulnerabilities of older adults. Unfortunately, the valuable contributions of older adults to post-disaster recovery and healing are often overlooked and undervalued. Our aim in this scoping review is to shed light on the critical contributions of older forced migrants to post-migration recovery. We set the scene by introducing the two significant global demographic changes of the twenty-first century: forced migration and ageing. We provide a discourse on older forced migrants, ageing in situations of forced migration, and some of the challenges faced by older forced migrants. We then present some of the substantial roles of older forced migrants in post-migration recovery, including building resilience, contributing to culture and language transfer, providing emotional support, offering mentorship and leadership, participating in community building, and fostering social integration. We close by highlighting some of the lessons that can be drawn from understanding the unique roles played by older adults in post-forced migration recovery and the key actions necessary to promote these roles.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

At the end of 2021, according to the United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees (UNHCR 2023a), global trends show that 108.4 million people have been forcibly displaced worldwide. This is essentially a result of continued global violence, conflict, human rights violations, persecution, climate change, and other public disturbance events (UNHCR 2019b). The international conflict between the Russian Federation and Ukraine has also dramatically impacted the global data on forced migration, creating one of the largest and fastest human displacement crises since World War II (UNHCR 2023b). The crises have impacted an estimated 11.6 million Ukrainians (5.9 million displaced persons and 5.7 million refugees) (UNHCR 2023b).

At the same time, another global demographic change has resulted in the world population ageing at an unprecedented rate, with over one billion older adults aged 60 years and over recorded in 2020 (WHO 2021); many older adults fall victim to disasters like forced migration (HelpAge International 2018a, 2018b). For example, in 2017, it was estimated that 8.5% of global forced migrants were older adults aged 60 years and over (UNHCR 2017). The number of older forced migrants will likely continue to increase as the two significant global demographic changes—forced migration and ageing—intersect. This is also a significant concern because it is predicted that 80% of older adults will live in low-and-middle-income countries, which are projected to account for an estimated 85% of global conflicts and violence by 2050 (WHO 2021; World Bank 2021).

Hence, a growing body of recent scholarship has started to examine the challenges of older forced migrants (Burton and Breen 2002; Shemirani and O'Connor 2006; Cook 2010; Kuittinen et al. 2014; Ekoh et al. 2021). These recent studies, and others examining older adults in various disaster scenarios such as pandemics, natural hazard-related disasters, and climate change (Bei et al. 2013; Ekoh et al. 2021; Montoro-Ramírez et al. 2022), concentrate on the vulnerabilities of older forced migrants. For example, Burton and Breen (2002) explored the precarious situation of older refugees during emergencies like refugeeism.Footnote 1 Meanwhile, Ekoh et al. (2021), Ekoh et al. (2022), and Shemirani and O’Connor (2006) delved into the abuse, exclusion, and loss of social networks experienced by individuals ageing as refugees. Other studies have examined the psychological difficulties faced by older refugees (Kuittinen et al. 2014), their lack of social support, and mental health challenges (Wang et al. 2017), and how migration negatively affects the later life of older women (Cook 2010).

While it is crucial to investigate the challenges and needs of older adults in disaster situations, the contribution of this population to post-disaster management remains under-discussed. Limited scholarship on the contributions of older forced migrants, combined with neoliberal humanitarian market-driven governance, has led to low interest in research aimed at understanding or developing the potential of older forced migrants to contribute to their communities. For example, donors do not prioritize initiatives that support the potential for the economic contribution of older forced migrants because of the perceived reduced life span of older forced migrants (Lupieri 2022). This is because these donors do not see the value of money in older forced migrant programs and perceive it as unsustainable to fund the training of older adults, who they view as limited in their ability to contribute to the labor force (Lupieri 2022). However, this market-driven understanding of value is problematic as it undermines the diverse ways that older adults contribute to the community. Hence, the roles of older forced migrants, as enumerated in this article, are examined beyond this monetary-based value to espouse the critical importance of older forced migrants in post-migration healing and in contributing to the well-being of other forced migrants and their communities.

Growing research interest in understanding the challenges of older forced migrants has sidetracked the complete experiences of older forced migrants. While it is very important to draw scholarly and humanitarian attention to the challenges of older refugees, it is also crucial to recognize their agency, assets, and potential in the post-migration period. Therefore, this article goes beyond the vulnerabilities of older forced migrants to prioritize their strengths, highlighting their roles in reducing harm and increasing well-being during the post-migration period. We start by providing a discourse on ageing in situations of forced migration; then, we highlight the challenges of older forced migrants. Drawing from the little extant literature on the topic and developing inferences from other adults’ responses in similar situations of post-disaster management, we discuss some of the contributions of older forced migrants in mitigating harm and promoting well-being post-forced migration.

2 Methodology

To account for the limited research on this topic, our study approach aimed to incorporate ample literature highlighting the valuable insights of older forced migrants. We employed five of the six steps in the methodological framework for scoping reviews developed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), including formulating the research question, identifying relevant studies, selecting articles, extracting and charting data, and summarizing and reporting outcomes. Furthermore, we used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews—PRISMA-Scr (Tricco et al. 2018), to present our findings accurately. The following research questions were used for this review:

-

(1)

What are the experiences of people ageing in the situation of forced migration?

-

(2)

What are the valuable contributions made by older forced migrants?

-

(3)

What lessons can be drawn from the value provided by older forced migrants?

To ensure a thorough body of evidence, we conducted a search without restrictions based on location, year of publication, or empirical studies. The inclusion criteria included literature written in English, a discussion of the contribution of older adults in post-crisis recovery, and full-text availability. Our search was conducted across various databases such as Web of Science, Sociology Abstracts, Abstracts of Gerontology, Social Services Abstracts, socINDEX, PsychINFO, and Social Work Abstracts. The resulting citations were exported to Zotero, where duplicates were removed. We also checked references of included literature for missed literature.

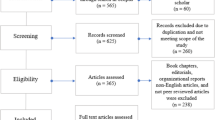

We used the web software Rayyan QCRi for the title and abstract screening according to the inclusion criteria. Our data extraction was done in Excel, and we focused on evidence that answered the research questions. We then read, interpreted, and synthesized the extracted data before charting it into themes that addressed the key issues. The PRISMA flow in Fig. 1 shows the literature review process.

3 Results

We identified 678 references from our database search. The references were checked for duplication with Zotero; we reviewed the titles and abstracts of 548 records. A further 397 articles were excluded in the abstract and title review with Rayyan QCRi, and 133 were excluded during the full-text review. This left us with a total of 18 articles for the literature review, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 provides a concise summary of the 18 articles analyzed in this review. These articles were published over the span of 11 years, from 2011 to 2022. Among them, nine are empirical studies, six are grey literature,Footnote 2 one is a theoretical paper, one is a newspaper report, and one is a blog post. Notably, a substantial portion of these articles were published by reputable journal publishers, although several of these articles are characterized as grey literature.

3.1 Ageing in Situations of Forced Migration

Ageing is associated with socioeconomic and health challenges (Hatzidimitriadou 2010); however, ageing out of place and in migration situations has been found to escalate these challenges (HelpAge International 2018a). In this section, we conceptualize who older forced migrants are and describe how forced migration impacts the health and well-being of life.

3.1.1 Definition of Older Forced Migrants

According to the UNHCR (2020), older forced migrants are recognized as people aged 60 years and over who have been forced to leave their homes or home regions due to forced displacement to settle in other parts of their country or a new country. However, the use of chronological age, which is colonial and Western, may be inaccurate in collecting data on forced migrants from different cultural backgrounds for several reasons. First, older forced migrants are typically among the least educated migrants, and many can only guess their age (HelpAge International 2018b). This also happens because, in non-Western societies, age is psychosocially construed, demonstrated by how a person feels and how society culturally defines ageing based on appearance and milestones like having children (Dziechciaż and Filip 2014); hence, chronological age is not prioritized (Helman 2005). Second, migration policies typically privilege granting asylum and refugee status and job opportunities to younger forced migrants because young people are assumed to provide labor, leading to economic growth (HelpAge International and IDMC 2012; Oberman 2020). To avoid being rejected by host countries or regions and limit economic discrimination, older forced migrants may be obligated to reduce their reported age (HelpAge International and IDMC 2012). Finally, the trauma, stress, health, and nutritional challenges associated with forced migration may expedite the biological ageing process, leading to older forced migrants experiencing age-related cognitive and health declines earlier than the non-migrant population (UNHCR 2015; UNHCR and HelpAge International 2021).

Older forced migrants in this article are classified into refugees, displaced persons, and asylum seekers. Refugees are forced migrants who cross the international border to settle in a new country. The United Nations’ principle of non-refoulement protects them from being forcefully repatriated to their country of origin (UNHCR 1951). Similar to refugees, asylum-seekers are also forced to cross international borders to a new country; however, the host country has not approved their refugee claim and, therefore, do not enjoy the same privileges as refugees and are not protected by United Nations principles on refugees (Asplet 2013). Displaced persons, on the other hand, are forced migrants who, due to violence, conflict, war, climate change, or other events of public disturbances, are forced to leave their homes or home region but remain within their country’s borders (UNHCR 2020). They are supported and protected by their countries’ governments. Additional categories of forced migrants may encompass those who are stateless or victims of trafficking (Turton 2003). In the context of this article, we use the term “older migrants” to refer to all older individuals who have migrated due to force, including asylum seekers, refugees, and displaced persons. Furthermore, we use the term “migration” to refer to “forced migration.”

As previously mentioned, 8.5% of those displaced from their homes or regions globally are older migrants (UNHCR 2017). However, it is important to note that this percentage may be underestimated because this information was reported when the global number of forced migrants was at 68.5 million, which is likely higher currently but unreported due to the insufficient documentation of older migrants. Older migrants are usually unseen because there is a tendency to focus on women and children as the most vulnerable populations in migration crises (Migration Data Portal 2022). Furthermore, data on migrants’ sex and age are often limited, typically ending at age 49, with most nutrition surveys targeting children under five and those living with HIV under the age of 45 (Field Exchange 2012). Together, this results in older migrants being overlooked (Handicap International and HelpAge International 2014; Ekoh et al. 2021), putting their needs and well-being at risk.

3.1.2 Unequal Ageing: Ageing in Migration

Migration takes older adults away from familiar environments, their community, and, frequently, their social support systems. Many older migrants face socioeconomic conditions that are different from what they would have experienced in their countries of origin (HelpAge International 2018a). This leads to complexities that may deny older adults successful ageing, increase their poverty rate, increase the risk for or exacerbate physical or mental health challenges, expose them to neglect and abuse, and result in poor health-seeking behaviors and lower life satisfaction (Sundquist et al. 2005; Tong et al. 2021).

Migration typically leads to an increased need for social support; however, ageing in situations of migration dramatically reduces older adults’ social networks and support systems (Sood and Bakhshi 2012). This is more challenging for older migrants because migration denies them the opportunity to plan for retirement, thus requiring them to adjust to a new and unfamiliar environment with a new language, culture, and limited social support systems.

Furthermore, older adults seek to rebuild their lives and communities post-crisis; however, migration offers them limited opportunities to do so (UNHCR 2002). Ageing in migration may also be characterized by experiences of ageing that intersect with their status as migrants, denying them employment and economic opportunities (Lössbroek et al. 2021; Baspineiro 2022; Ekoh and Okoye 2022). This is because many ageing migrants who characteristically migrate from low and middle-income countries may lack the skills, training, and qualifications required to earn a living in their host countries (HelpAge International 2018a). Even when they have the required qualifications, compounded by ageism, their qualifications, like those of their younger counterparts, may not be recognized in the new country, compelling older migrants to take up lower job positions (UNHCR 2002). Gustafsson et al. (2021) suggested that older adults ageing in migration may become economically dependent on younger people, leading them to lose their agency and causing them to age with shame and humiliation. Co-migrant younger people who also experience migration-associated vulnerability may be preoccupied with their own survival, leading to the abandonment of older migrants (UNICEF and IDMC 2019). All these factors contribute to economic difficulties in ageing in situations of migration.

Ageing in migration may also deny older adults their traditionally ascribed positions as knowledge holders and leaders within their community. This may lead to older migrants losing their status and authority, increasing negative attitudes towards them (UNHCR 2015; HelpAge International 2018b). They also may become dependent on younger migrants, who usually find it easier to integrate into new environments for cultural interpretation and access to information (Pot et al. 2020). Migration may also deny older adults the opportunity to age within their religious and cultural milieu; this is important given that extant literature shows the heightened importance of culture, religion, and spirituality in old age (Malone and Dadswell 2018; Lima et al. 2020; Okolie et al. 2023).

3.1.3 Health and Psychosocial Challenges Facing Older Migrants

Ageing in migration is frequently associated with deteriorating health conditions and increased disabilities, with HelpAge International (2014) reporting that an estimated 77% of migrants are affected by disabilities, chronic diseases, and injuries. The intersection of migration stress, trauma, poor nutrition, and ageing may expose many older migrants to precarious health conditions, suffering from a variety of communicable and non-communicable diseases, leading to increased morbidity and mortality (Pieterse and Ismail 2003; Bukonda et al. 2012). The study by Pieterse and Ismail (2003) revealed the increased prevalence of chronic illness in later life, while Bukonda et al. (2012) indicated that older migrants are more susceptible to illnesses such as fever, malaria, and diarrhea, compared to non-migrants. Further, Du Cros et al. (2013) reported that older migrants aged 50 and over had a five times higher mortality rate than migrants below age 50. These health challenges among older migrants are more complicated than those of their younger aged counterparts because older migrants with more health problems have less access to healthcare services (ICEDLSH and TMHI 2018).

Disabilities among migrants are 15% higher than the global average (Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data 2022). Although exact estimates are unknown, this figure is likely greater among older migrants whose exposure to violence leading to migration increases their disabilities, as evidenced by UNHCR and HelpAge International (2021) research, which found an intersection between old age and disabilities in migration. These disabilities affect older migrants’ access to resources as they may struggle with physical barriers such as long queues and lines (National Disaster Risk Reduction Centre 2016; HelpAge International 2016). Migration also leads to the early onset of cognitive impairments such as dementia, which in turn impacts migrant access to help-seeking information (Good et al. 2016; HelpAge International 2018b). Older migrants living with disabilities are further disproportionately discriminated against, exacerbating their preexisting vulnerability (UNHCR 2016). Further, there is little hope for appropriate interventions because there are limited guidelines to address their age-specific needs (ICEDLSH and TMHI 2018).

A growing number of studies have also found an increased prevalence of mental health problems among older migrants. Cummings et al. (2011), for example, found higher rates of depression among older migrants as a result of the losses and trauma associated with migration. Their loss of social networks and support due to migration was also associated with depressive symptoms (Ekoh et al. 2023). Additionally, Cummings et al. (2011) found that living conditions after migration, characterized by low income, poor social support, lack of language proficiency, and poor physical health conditions, increase levels of depression. Older migrants also experience amplified anxiety levels, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and general psychological distress due to their pre-migration, migration, and post-migration experiences of violence, loss, and other struggles (Ahmad et al. 2020).

Older migrants also experience a range of social issues. They may experience significant levels of ageism in employment and access to resources, healthcare services, and increased exploitation and exclusion (Hutton 2008; ICEDLSH and TMHI 2018; UNHCR 2019a; Ekoh et al. 2023). They may also be exposed to abuse, racism, human rights violations, and xenophobia because of their religion and ethnicity (UNHCR 2020; Osterlund 2022). Older migrants also considerably have more language difficulties than younger migrants, and many host communities and countries do not have language integration plans and programs for this population (Pot 2020; Boutmira 2021). Similarly, education and training programs are typically designed for younger migrants, with older adults stereotyped as being incapable of learning new languages and skills (UNHCR 2019b; Lergetporer et al. 2021). All these significantly impact older migrants’ abilities to resettle and integrate into the new environment. These deficits and challenges of older migrants, as detailed in the literature, highlight the need for intervention tailored to this population. In addition to the growing critical importance of research and interventions to address the needs of older migrants, their agency and post-migration contributions must also be recognized and advanced.

3.2 Contribution of Older Refugees in Post-migration Recovery

Forced migration can be incredibly challenging for older adults and we have established the vulnerabilities associated with ageing in situations of forced migration. However, older adults are not only vulnerable and dependent members of the community post-migration; they also play critical roles in post-migration recovery. Hence, in supporting older adults affected by forced migration, it is imperative that we recognize and consolidate their roles in healing, providing support and community leadership after forced migration.

3.2.1 Therapeutic Caregiving

Many children and younger people in migration are orphaned due to events leading to migration (UNHCR 2019b; UNICEF and IDMC 2019), leaving a community-based caregiving gap for these children and other young people. Older migrants, especially older women who sometimes may have also lost their children and/or grandchildren, often provide the therapeutic caregiving needed by the children and young people (HelpAge International 2018a). They offer encouragement, daily support, comfort, and daily experiences that help young people grow into healthy adults (UNICEF and IDMC 2019). Versed in culture, values, and belief systems, older migrants who play the roles of therapeutic caregivers also advocate for youth healing and wellness. With their experiences, older migrants can identify children and young people’s strengths, help them nurture these strengths, and encourage them to take on challenges. Furthermore, given that many older migrants migrate from communal societies (UNHCR 2002), they can aid young people in building meaningful relationships with their new community post-migration. Older migrants’ caregiving responsibilities and experience also make them critical in designing child protection strategies, leading HelpAge International (2018a) to recommend investment in programming for older people.

3.2.2 Emotional Support and Mentorship

In many cultures, older adults are valued for their wisdom and life experiences, making them ideal for providing emotional support and mentorship post-migration. Older migrants can provide mentorship and guidance to younger people, as they draw from their understanding of historical events to teach younger people about things younger people did not experience firsthand in order to prepare them for life challenges (HelpAge International and IDMC 2012). They may also provide emotional support by listening to and advising younger co-migrants in their community (Ekoh et al. 2021). The emotional support and mentorship role offered by older migrants is critical, given the trauma associated with migration and the lack of professionals focused on providing emotional support to migrants (UNHCR 2022). Older migrants are usually well positioned to provide this emotional support because of their peculiar life experiences, shared lived experiences as fellow migrants, and typically less preoccupation with paid employment. Older migrants also support younger women without a male head of household in patriarchal societies, as highlighted by IDMC (2011). For example, IDMC (2011) found that older migrants supported younger women who did not have male chaperones or guardians to navigate the social rules of purdah by accompanying them to resource distribution points in the Sindh Province of Pakistan. Similarly, HelpAge International (2018a) reported that older migrant women in South Sudan mentored and advised younger women, yielding significant social and behavioral change.

3.2.3 Culture and Language Transfer

In many societies, older adults are the custodians of culture and tradition (Löckenhoff et al. 2009); hence, older migrants can play a critical role in the intergenerational transfer of cultural knowledge, values, traditional norms, and language. They migrate with a wealth of knowledge of their culture, which they can transmit to the host community to enrich its cultural fabric and to younger co-migrants (UNHCR 2002). Older migrants can also advance cultural exchange, tolerance, and cross-cultural understanding and dismantle stereotypes by introducing new cultures and arts to the host communities (UNHCR and HelpAge International 2021). This cultural and language transfer has been found to help younger migrant children stay grounded and develop into well-functioning adults (Cunningham and King 2018), while also developing their identity in the host community (UNHCR 2002). The connection to migrants’ traditional culture, which older migrants provide, can also help relieve the stress and feeling of dislocation associated with integration into a new environment (UNHCR 2002). Culture can also be transferred through storytelling, as has been found in Ethiopia, where older adults are engaged in storytelling to pass on their traditional knowledge and stories (HelpAge International 2018a). Increasing discourse on migration and language focuses on older migrants’ lack of proficiency in the language of receiving communities and its impact on their lives, with little attention on the importance of their first language to their new community. Older migrants can help maintain their first language and support migrants who are struggling with navigating their identity through language support.

3.2.4 Building Resilience Through Storytelling

Drawing on the experiences of older migrants is essential for building resilience and coping with the impact of migration. This can either be passive as other migrants get inspired from observing the resilience shown by older migrants in adversity and/or actively through the stories shared by older adults about resilience in the face of crises. People’s experiences inform resilience; thus, telling stories about personal experiences helps people develop positive changes (Theron et al. 2017), empowering them towards appropriate goals and aspirations (Ali 2014; Nelson and Arthur 2003). In many societies, older adults are renowned storytellers and use storytelling to teach and encourage younger people (HelpAge International 2018a). Hence, older migrants can use storytelling to empower other migrants to build resilience, reclaim their voices, and reflect on their experiences to find agency and strength (Seedat et al. 2004). Storytelling does not only help younger people reflect on the stories they hear about how the storyteller overcame adversities and how to adopt the insights embedded in the stories in their own lives, but it also helps the older storyteller build resilience as well. Leseho and Block (2005) noted that telling personal stories gives storytellers the opportunity to be listened to, which can, in and of itself, be therapeutic. Older migrants can also reflect on their experiences, make sense of these experiences, improve their understanding of such experiences, develop emotional insights, and discover new perspectives (Jackson and Mannix 2003).

3.2.5 Paid and Unpaid Work

Older migrants suffer from discrimination in employment; however, in most cases, they are capable of engaging in paid and unpaid work. Older adults also migrate with a wealth of experiences and professional skills that they can use to earn an income and contribute to the local economy (Flynn and Wong 2022). For example, some initiatives in the United States have leveraged the contribution of older refugees, especially older women, as advisers and supporters of children and grandchildren to establish childcare co-operatives (UNHCR 2002). In this process, older women refugees received training as assistants in social support agencies (UNHCR 2002).

There is also growing evidence of older migrants engaging in unpaid work in their families and communities due to unemployment and, in an effort to increase the chances of younger co-migrants pursuing and securing paid jobs (Wang et al. 2017; Koh et al. 2018). For instance, Koh et al. (2018) reported that older migrants, especially older women, work as caregivers for children and people living with disabilities, as well as provide home maintenance, while Wang et al. (2017) revealed that older migrants prepared food for their adult children, relieving them of the extra responsibilities of domestic work so their adult children can focus on paid employment.

3.2.6 Leadership, Community Building, and Social Integration

Older migrants play crucial roles in community building, acting in leadership positions and advising community leaders. In many displacement camps, older adults, recognized as camp elders (elders in the sense of community leaders), draw from their experiences to serve in advisory roles (Karasapan 2016). In this way, they help foster unity and provide a sense of belonging through the establishment of social gatherings. Further, when there is disagreement within the migrant populations or between migrants and host communities, older migrants play critical roles in adjudicating disputes through facilitating communication, mediating, and promoting dialogue and cooperation (Karasapan 2016; UNHCR 2019a). They also effectively negotiate with their host community and foster unity between migrants and the host community (Karasapan 2016). This recognition of older migrants’ critical engagement in community leadership led the UNHCR (2019a) to recommend recognizing the significant roles older migrants play in strengthening communities and advancing practices to reinforce these leadership roles. The commissioner also recommended avoiding inadvertently undermining the leadership responsibilities of older migrants by duplicating leadership structures.

3.2.7 Peer Support

Older migrants also provide informal and formal peer support to other older migrants. An informal peer support network is developed by older migrants without external support, while formal peer support is organized and supported by external bodies. Examples of informal peer support can be found in studies that have shown that older people in displacement visit each other to provide care, food, and other resources, especially in times of ill health (Cook 2010; Ekoh et al. 2023). For instance, Ekoh et al. (2023) reported that older migrants share their limited resources with other older adults to ensure that they have the basics. In addition, the older migrants were responsible for providing emotional support to their peers, who received a lot of respite from sharing their stories every night with one another, especially during the initial displacement.

Formal peer support has also been integral to HelpAge International’s intervention as they create social spaces for older migrants to gather and identify resources, make decisions, and plan interventions for the various issues affecting them. A noteworthy example of peer support in action is the HelpAge initiative, which created a community outreach network comprising older migrants in Haiti known as “Friends” (HelpAge International and IDMC 2012). “Friends” collected data and provided home-based peer support to highly vulnerable older people in displacement camps. Other successes of this peer support included establishing a donation cash box for contributions used to support older adults in financial difficulties, integrating older people into the labor market, and literacy programs for illiterate older people.

3.3 What Can We Learn from Older Migrants’ Potential and Key Actions?

In disaster situations such as migration, which may be caused by continued violence and human rights violence in different parts of the world, or climate change and its impact on public health and safety, older adults have unique capacities to respond and aid in the post-crisis healing process. The literature reviewed in this article documents that older migrants can take up formal and informal leadership positions where their wisdom and experiences can be harnessed to benefit their communities. Therefore, older migrants must be consulted and collaborated with in developing policies and programs for older migrants and migrants in general. They must be subjects as well as actors in risk management and reduction policies (UNHCR 2002). To ensure that older adults are recognized in situations of migration, they must be included in the Global Compact on Refugees (United Nations Human Rights 2022) and should also be consulted in an effort to understand and address the barriers to their access to healthcare services, mobility needs, and technology.

As identified by HelpAge International’s (2018a) study, many humanitarian aid actors do not recognize the value of older adults; thus, they do not often consult them in planning and implementing intervention programs. The value of older migrants in post-migration, identified here, shows that they are a vulnerable and valuable population. Therefore, while recognizing their risks and challenges, we must also take note of their assets, agency, strengths, and potential. This will inform our integration of older migrants in the sectoral and multi-sectoral assessments, plans, and decision making on issues affecting them and migrants in general. We can leverage the peer support model to incorporate older adults in the execution of social intervention and in caring for the most vulnerable older migrants. Furthermore, given that older migrants, especially older women, make up a good proportion of child caregivers, child protection efforts and strategies in situations of migration can significantly benefit from the cooperation of older migrants. More actions that can be taken to promote older migrants’ contributions are presented in Table 2.

It is essential to recognize that very little primary empirical research has been done to explore the roles of older adults in post-migration recovery. Many of the contributions of older migrants reported in this article were from grey literature, and the research outcomes focused on other issues; findings were not derived from studies designed to explore this topic, showing a gap in research and investigation. Hence, future empirical studies on the experiences of older migrants, displaced persons, and refugees should explore this population’s unique values, assets, and contributions. Understanding the contribution of older migrants through research is needed, and the research must be collaborative and conducted in ways that prioritize the voices of older migrants themselves. Researchers can adopt a wide range of methodologies and approaches to engage directly and indirectly with older migrants, considering their age, gender, language, mobility, and disabilities.

Researchers play a role in developing a greater understanding of the place of older migrants in post-migration research. A recognition of their assets and agency will ensure that older migrants are not perceived as just research subjects but can be active collaborators in research (HelpAge International and IDMC 2012). Their position as people with the experiences of ageing in migration makes them experts in understanding their needs and challenges and positions them to design interventions to address them (HelpAge International and IDMC 2012).

4 Conclusion

Population ageing and migration are two of the most significant demographic changes of the twenty-first century (IZA Institute of Labour Economics 2021), and they intersect to impact the lives and well-being of older migrants significantly. Growing calls from researchers and organizations such as HelpAge International, UNHCR, and IDMC have increased the focus on the needs and challenges of older refugees and displaced persons. The sparse discussion of the contributions and value of older migrants, however, creates new challenges as policymakers and governments may only perceive this population through a vulnerability lens. This may lead to the view of older migrants as both vulnerable and as burdens to the host country’s healthcare and economic resources. This article, while recognizing and highlighting some of the unique challenges and vulnerabilities of older forced migrants, has presented a more nuanced discourse by illuminating the many critical contributions older adults can bring in post-migration recovery. The roles range from therapeutic care and building resilience to economic contributions, leadership, and community building, which reveal their inherent strengths, assets, agencies, and potentials. These contributions must be recognized and reinforced to promote sustainable solutions for older people, as well as their communities of migrants in general and the larger social environment in which they are embedded.

Notes

Refugeeism is the noun used to describe a situation where people cross international borders to avoid persecution or danger.

Grey literature is information produced and distributed through non-traditional academic publishing channels. They may include classified documents, white papers, internal reports, newsletters, government documents, and so on. Grey literature is not peer-reviewed and may have biases or varying quality.

References

Ahmad, F., N. Othman, and W. Lou. 2020. Posttraumatic stress disorder, social support and coping among Afghan refugees in Canada. Community Mental Health Journal 56(4): 597–605.

Ali, M.I. 2014. Stories/storytelling for women’s empowerment/empowering stories. Women’s Studies International Forum 45: 98–104.

Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8(1): 19–32.

Asplet, M. 2013. Internal displacement: Responsibility and action. Geneva: UNCHR. http://archive.ipu.org/PDF/publications/Displacement-e.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

Baspineiro, R. 2022. “Invisible” migration and bodies that expire: The reality of older migrants in Latin America. Equal Times, 25 May 2022. https://www.equaltimes.org/invisible-migration-and-bodies#.YsORrhPMJbV. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

Bei, B., C. Bryant, K. Gilson, J. Koh, P. Gibson, A. Komiti, H. Jackson, and E. Judd. 2013. A prospective study of the impact of floods on the mental and physical health of older adults. Ageing and Mental Health 17(8): 992–1002.

Boutmira, S. 2021. Older Syrian refugees’ experiences of language barriers in postmigration and (re)settlement context in Canada. International Health Trends and Perspectives 1(2): 404–417.

Bukonda, N.K.Z., B. Smith, T.G. Disashi, J. Njue, and K.H. Lee. 2012. Incidence and correlates of diarrhea, fever, malaria and weight loss among elderly and non-elderly internally displaced parents in Cibombo Cimuangiin the Eastern Kasai Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Journal of Population Ageing 5(1): 47–66.

Burton, A., and C. Breen. 2002. Older refugees in humanitarian emergencies. Lancet 360: s47–s48.

Cook, J. 2010. Exploring older women’s citizenship: Understanding the impact of migration in later life. Ageing and Society 30(2): 253–273.

Cummings, S., L. Sull, C. Davis, and N. Worley. 2011. Correlates of depression among older Kurdish refugees. Social Work 56(2): 159–168.

Cunningham, U., and J. King. 2018. Language, ethnicity, and belonging for the children of migrants in New Zealand. SAGE Open 8(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018782571.

Du Cros, P., S. Venis, and U. Karunakara. 2013. Should mortality data for the elderly be collected routinely in emergencies? The practical challenges of age-disaggregated surveillance systems. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 107(11): 669–671.

Dziechciaż, M., and R. Filip. 2014. Biological psychological and social determinants of old age: Bio-psycho-social aspects of human aging. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine 21(4): 835–838.

Ekoh, P.C., and U.O. Okoye. 2022. More than just forced migrants: Using intersectionality to understand the challenges and experiences of older refugees in Western societies. Journal of Social Work in Developing Societies 4(2). https://journals.aphriapub.com/index.php/JSWDS/article/view/1603.

Ekoh, P.C., P.U. Agbawodikeizu, E.O. George, C.D. Ezulike, and U.O. Okoye. 2021. More invisible and vulnerable: The impact of COVID-19 on older persons in displacement in Durumi IDP camp Abuja, Nigeria. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults 22(3/4): 135–146.

Ekoh, P.C., C. Ejimkaraonye, P.U. Agbawodikeizu, N.E. Chukwu, T.J. Okolie, E.O. Ugwu, C.G. Otti, and P.L. Tanyi. 2023. Exclusion within exclusion: The experiences of internally displaced older adults in Lugbe camp, Abuja. Journal of Aging Studies 66: Article 101160.

Ekoh, P.C., A.O. Iwuagwu, E.O. George, and C.A. Walsh. 2022. Forced migration-induced diminished social networks and support, and its impact on the emotional wellbeing of older refugees in Western countries: A scoping review. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2022.104839.

Field Exchange. 2012. The impact of displacement on older people. https://www.ennonline.net/fex/44/older#:~:text=HelpAge%20and%20IDMC%20research%20and,rarely%20consulted%20within%20IDP%20operations. Accessed 24 Feb 2024.

Flynn, M., and L. Wong. 2022. Older migrants and overcoming employment barriers: Does community activism provide the answer? Frontiers in Sociology 7: Article 845623.

Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data. 2022. Data on disability and migration: What do we know? https://www.data4sdgs.org/blog/data-disability-and-migration-what-do-we-know. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

Good, G.A., S. Phibbs, and K. Williamson. 2016. Disoriented and immobile: The experiences of people with visual impairments during and after the Christchurch, New Zealand, 2010 and 2011 earthquakes. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness 110(6): 425–435.

Gustafsson, B., V. Jakobsen, H.M. Innes, P.J. Pedersen, and T. Österberg. 2021. Older immigrants—New poverty risk in Scandinavian welfare states?. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48(19): 4648–4669.

Handicap International and HelpAge International. 2014. Hidden victims of the Syrian crises: Disabled, injured and older refugees. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/40819. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

Hatzidimitriadou, E. 2010. Migration and ageing: Settlement experiences and emerging care needs of older refugees in developed countries. Hellenic Journal of Psychology 7(1): 1–20.

Helman, C.G. 2005. Cultural aspects of time and ageing. EMBO Reports 6: S54–S58.

HelpAge and Handicap International. 2012. A study of humanitarian financing for older people and persons with disabilities, 2010–2011. https://www.helpage.org/silo/files/a-study-of-humanitarian-financing-for-older-people.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

HelpAge International. 2016. Older voices in humanitarian crisis: Calling for change. London: HelpAge International.

HelpAge International. 2014. Hidden victims: New research on older, disabled and injured Syrian refugees. https://www.helpage.org/news/hidden-victims-new-research-on-older-disabled-and-injured-syrian-refugees/. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

HelpAge International. 2018a. Older people in displacement: Falling through the cracks of emergency responses. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12292.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

HelpAge International. 2018b. Missing millions: How older people with disabilities are excluded from humanitarian response. https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/media/23446. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.2024.

HelpAge International and IDMC (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre). 2012. The neglected generation: The impact of displacement on older people. https://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/the-neglected-generation-the-impact-of-displacement-on-older-people. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

Hutton, D. 2008. Older people in emergencies: Considerations for action and policy development. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/WHO-Older-Persons-in-Emergencies-Considerations-for-Action-and-Policy-Development-English.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

ICEDLSH (International Centre for Evidence in Disability at London School of Hygiene) and TMHI (Tropical Medicine and HelpAge International). 2018. Missing millions: How older people with disabilities are excluded from humanitarian response. London: ICEDLSH and TMHI.

IDMC (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre). 2011. Flood-displaced women in Sindh Province, Pakistan: Research findings and recommendations. https://reliefweb.int/report/pakistan/impact-flood-induced-displacement-women-sindh-province. Accessed 24 Feb 2024.

IZA Institute of Labor Migration. 2021. Population aging and migration. https://docs.iza.org/dp14389.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

Jackson, D., and J. Mannix. 2003. Mothering and women’s health: I love being a mother but... there is always something new to worry about. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 20(3): 30–37.

Karasapan, O. 2016. The older refugee and community resilience. Arab Voices, 24 June 2016. https://blogs.worldbank.org/arabvoices/older-refugee-and-community-resilience. Accessed 24 Feb 2024.

Koh, L.C., R. Walker, D. Wollersheim, and P. Liamputtong. 2018. I think someone is walking with me: The use of mobile phone for social capital development among women in four refugee communities. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 14(4): 411–424.

Kuittinen, S., R.-L. Punamäki, M. Mölsä, S.I. Saarni, M. Tiilikainen, and M.-L. Honkasalo. 2014. Depressive symptoms and their psychosocial correlates among older Somali refugees and native Finns. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 45(9): 1434–1452.

Lergetporer, P., M. Piopiunik, and L. Simon. 2021. Does the education level of refugees affect natives’ attitudes? European Economic Review 134: Article 103710.

Leseho, J., and L. Block. 2005. “Listen and I tell you something”: Storytelling and social action in the healing of the oppressed. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling 33(2): 175–184.

Lima, S., L. Teixeira, R. Esteves, F. Ribeiro, F. Pereira, A. Teixeira, and C. Magalhães. 2020. Spirituality and quality of life in older adults: A path analysis model. BMC Geriatrics 20: Article 259.

Löckenhoff, C.E., F.D. Fruyt, A. Terracciano, R.R. McCrae, M.D. Bolle, M.E. Aguilar-Vafaie, L. Alcalay, J. Allik, et al. 2009. Perceptions of aging across 26 cultures and their culture-level associates. Psychology and Aging 24(4): Article 941.

Lössbroek, J., B. Lancee, T. van der Lippe, and J. Schippers. 2021. Age discrimination in hiring decisions: A factorial survey among managers in nine European countries. European Sociological Review 37(1): 49–66.

Lupieri, S. 2022. “Vulnerable” but not “Valuable”: Older refugees and perceptions of deservingness in medical humanitarianism. Social Science & Medicine 301: Article 114903.

Malone, J., and A. Dadswell. 2018. The role of religion, spirituality and/or belief in positive ageing for older adults. Geriatrics 3(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics3020028.

Migration Data Portal. 2022. Older persons and migration. https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/older-persons-and-migration. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

Montoro-Ramírez, E.M., L. Parra- Anguita, C. Álvarez- Nieto, G. Parra, and I. Lopez-Medina. 2022. Effects of climate change in the elderly’s health: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 12: Article e058063.

National Disaster Risk Reduction Centre. 2016. Assessing the impact of Nepal’s 2015 earthquake on older people and persons with disabilities and how gender and ethnicity factor into that impact. Study report submitted to HelpAge International. Kathmandu, Nepal: NDRC.

Nelson, A., and B. Arthur. 2003. Storytelling for empowerment: Decreasing at-risk youth’s alcohol and marijuana use. The Journal of Primary Prevention 24: 169–180.

Oberman, K. 2020. Refugee discrimination—The good, the bad, and the pragmantic. Journal of Applied Philosophy 37(5): 695–712.

Okolie, T.J., P.C. Ekoh, S.C. Onuh, and E.O. Ugwu. 2023. Perspectives of rural older women on the determinants of successful ageing in southeast Nigeria. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 38(2): 173–189.

Osterlund, P.B. 2022. Turkey: Man arrested after kicking elderly Syrian woman in video. Aljazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/1/turkey-man-arrested-after-kicking-elderly-syrian-woman-in-video. Access 17 Aug 2023.

Pieterse, S., and S. Ismail. 2003. Nutritional risk factors for older refugees. Disasters 27(1): 16–36.

Pot, A., M. Keijzer, and K. De Bot. 2020. The language barrier in migrant aging. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23(9): 1139–1157.

Seedat, S., W.P. Pienaar, D. Williams, and D.J. Stein. 2004. Ethics of research on survivors of trauma. Current Psychiatry Reports 6(4): 262–267.

Shemirani, F.S., and D.L. O’Connor. 2006. Ageing in a foreign country: Voices of Iranian women ageing in Canada. Journal of Women & Aging 18(2): 73–90.

Sood, S., and A. Bakhshi. 2012. Perceived social support and psychological well-being of aged Kashmiri migrants. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences 2(2): 1–7.

Sundquist, K., L.M. Johansson, V. DeMarinis, S.E. Johansson, and J. Sundquist. 2005. Posttraumatic stress disorder and psychiatric co-morbidity: Symptoms in a random sample of female Bosnian refugees. European psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists 20(2): 158–164.

Theron, L., K. Cockcroft, and L. Wood. 2017. The resilience-enabling value of African folktales: The read-me-to-resilience intervention. School Psychology International 38(5): 491–506.

Tong, H., Y. Lung, S.L. Lin, K.M. Kobayashi, K.M. Davison, S. Agbeyaka, and E. Fuller-Thomson. 2021. Refugee status is associated with double the odds of psychological distress in mid-to-late life: Findings from the Canadian longitudinal study on aging. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 67(6): 747–760.

Tricco, A.C., E. Lillie, W. Zarin, K.K. O’Brien, H. Colquhoun, D. Levac, D. Moher, and M.D.J. Peters et al. 2018. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 169(7): 467–473.

Turton, D. 2003. Refugees and “other forced migrants”. Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. https://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/files/files-1/wp13-refugees-other-forced-migrants-2003.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees). 1951. The 1951 refugee convention. https://www.unhcr.org/1951-refugee-convention.html. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees). 2002. Older refugees. https://www.unhcr.org/handbooks/ih/age-gender-diversity/older-refugees. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees). 2015. Older persons. https://emergency.unhcr.org/entry/43935/older-persons#:~:text=An%20older%20person%20is%20defined,or%20age%2Drelated%20health%20conditions. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees). 2016. Strengthening protection of persons with disabilities in forced displacement: The situation of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) with disabilities in Ukraine. https://www.unhcr.org/what-we-do/protect-human-rights/safeguarding-individuals/persons-disabilities/strengthening. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees). 2017. Global trends: Forced displacement in 2017. https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2017/. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees). 2019a. Older persons in forced displacement—Intersecting risks. Expert Group Meeting on Older Persons in Emergency Crisis. https://social.desa.un.org/sites/default/files/migrated/22/2019/05/UNHCR-Expert-Group-meeting-on-aging_Lange.pdf. Accessed 24 Feb 2024.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees). 2019b. Refugee education in crisis: More than half of the world’s school-age refugee children do not get an education. https://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2019/8/5d67b2f47/refugee-education-crisis-half-worlds-school-age-refugee-children-education.html. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees). 2020. Older persons. https://www.unhcr.org/older-persons.html. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees). 2022. Refugees need better mental health support amid rising displacement. https://www.unhcr.org/news/news-releases/refugees-need-better-mental-health-support-amid-rising-displacement. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees). 2023a. Data and statistics: Mid-year trends. https://www.unhcr.org/mid-year-trends. Accessed 14 Jan 2024.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees). 2023b. Operational data portal: Ukraine refugee situation. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine. Accessed 24 Jan 2023.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees) and HelpAge International. 2021. Working with older persons in forced displacement. Geneva: UNHCR. https://www.refworld.org/docid/4ee72aaf2.html. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) and IDMC (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre). 2019. Protecting and supporting internally displaced children in urban settings. https://www.unicef.org. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

United Nations Human Rights. 2022. Principles and guidelines, supported by practical guidance, on the protection of migrants in vulnerable situations. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Migration/PrinciplesAndGuidelines.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

Wang, S.C., J.W. Creswell, and D. Nguyen. 2017. Vietnamese refugee elderly women and their experiences of social support: A multiple case study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 32(4): 479–496.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2021. Ageing and health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

World Bank. 2021. Fragility, conflict and violence. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fragilityconflictviolence/overview#1. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

Acknowledgments

The first author thanks the Pierre Elliot Trudeau Foundation and the Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship for their generous support in funding his doctoral program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ekoh, P.C., Walsh, C.A. Valuable Beyond Vulnerable: A Scoping Review on the Contributions of Older Forced Migrants in Post-migration Recovery. Int J Disaster Risk Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-024-00549-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-024-00549-7