Abstract

This study examined the propensity of social media use by underserved communities by drawing on the literature on the digital divide and attribution theory. Specifically, this research explored the factors that can influence the use of social media for disaster management. The study used survey methodology to collect data and partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to analyze the data and test the hypotheses. The results of the study indicate: (1) that the propensity of social media use for disaster management is low for underserved communities; (2) a positive relationship between an individual’s effort and the intention to use social media for disaster management; and (3) a negative relationship between task difficulty and the intention to use social media for disaster management. The study expanded the literature on the use of social media in disaster management. The article also provides both theoretical and practical implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The ubiquitous nature of social media has changed the landscape of communication in the field of disaster management. Social media, also referred to as social networking, is an umbrella term for a multiplicity of services and web-based platforms that enable users to create public profiles and/or content and to connect with other users’ profiles and/or content (Blank and Reisdorf 2012). Examples of social media include platforms such as blogs, Twitter, Facebook, and other web 2.0 applications (Palen 2008; McCallum et al. 2016). Typically, these platforms can be accessed by various computing devices such as desktops, laptops, tablets, and smartphones, and recent years have seen an increase in the access of social media through mobile devices such as tablets and smartphones (Constine 2013, Moreira et al. 2017).

Organizations and individuals involved in managing disasters show optimism regarding the use of social media for enhanced communication and operations during disaster management (Reynolds and Seeger 2012; Houston et al. 2014; McCormick 2016; Marlowe et al. 2018). They tend to leverage their own social networks with social media to discover and offer information critical for crucial decisions on heeding warnings and planning evacuations (Ngamassi et al. 2016a). In recent years, social media have evolved from being just a passive medium of information exchange—that is, simply broadcasting static information of disaster occurrence—to an active emergency tool that has the ability to disseminate real-time warning information that creates real-time situational awareness of user activities, and receives requests for assistance (Houston et al. 2014; Xiao et al. 2015). The advantages of social media such as the ease of use, efficiency of communication, and facilitation of open online exchange of information, have made their use more pervasive in the field of disaster management (Yates and Paquette 2011; Denis et al. 2014; Hiltz et al. 2014; Ngamassi et al. 2016b). In disaster management, social media have been used in collecting data for assessing the situation of disasters and developing an operational picture, coordinating rescue operations, and communicating valuable information to as many people as possible (Berchtold et al. 2020).

Although social media have been increasingly used as essential communication and collaboration tools for disaster management and relief, not all communities have benefited equally due to the existence of social inequality in the access and usage of social media data (Xiao et al. 2015; Adekola et al. 2020). Social inequality leads to a “digital divide,” which refers to the gap between groups who have access to information and communication technology and groups who do not have access to this technology (van Dijk 2006; Xiao et al. 2015). The term underserved or vulnerable community refers to people who do not have access to this technology, and/or for whom circumstances involve challenges in seeking information with the specific technology or lack the capability to respond in the same way as the general population does (van Dijk 2006; Xiao et al. 2015; Karanasios et al. 2019; Karaye et al. 2019). Lower socioeconomic status people, people with disabilities, old people, isolated people, and marginalized people are some of the groups that fall within the underserved or vulnerable community category. Research shows that such communities tend to suffer disproportionately from disasters (Ngamassi et al. 2014; Deacon 2018; Karaye et al. 2019; Ramakrishnan et al. 2019). A report from The American Prospect, for example, indicated that about 46% of the most severely affected neighborhoods during the 2005 Hurricane Katrina floods were part of the African-American community (Squires 2017). Similarly, according to Klinenberg (2013), African-American communities were affected disproportionately during 2012 Hurricane Sandy and 2013 Winter Storm Nemo, even though the information concerning the locations and the instructions on how to stay safe was provided to them before the hurricanes. People in these underserved communities were not able to capitalize on these instructions due to lack of skills and not being tech-savvy (Klinenberg 2013).

Even though there has been a lot of research on the use of social media for disaster management (Ngamassi et al. 2016a, 2016b; Karanasios et al. 2019; Karaye et al. 2019; Ramakrishnan et al. 2019), a gap still remains in the literature when it comes to explaining the inefficiency in the use of social media for disaster management by underserved communities. Exploring the factors that influence the use of social media for disaster management may be the first step in trying to bridge this digital divide and motivate the use of social media for disaster management in underserved communities.

Drawing on the literature on the digital divide and attribution theory, this study examined the propensity of using social media by a sample of underserved, predominantly African-American, communities in southeast Texas and explored the factors that can influence the use of social media for disaster management. We propose five hypotheses. The first four hypotheses examine the relationships between the digital divide (underserved communities), ability, effort, and task difficulty with social media use for disaster management, respectively. The fifth hypothesis examines the moderating effect of underserved communities on the relationship between task difficulty and social media use for disaster management. A survey methodology was used to collect data. The partial least squares regression approach was used to analyze the data collected through the survey questionnaire.

In the next section, we outline the theoretical development of the research model, drawing on the literature on the digital divide and on attribution theory, and formulate five hypotheses. We then present the methodology used to collect the data and to test the hypotheses. In the subsequent sections, we provide the data analysis and discuss the results, followed by the implications of the study for theory and practice, and point out the limitations of this study and the directions for future research.

2 Theory Development

We conceptualized the research model (Fig. 1) by examining the literature on the digital divide and by drawing on attribution theory literature. Literature on the digital divide offers us the platform to examine the relationship between underserved communities and their use of social media for disaster management. Although underserved communities include populations with disabilities, weak socioeconomic backgrounds, elderly people, and marginalized communities (Karaye et al. 2019; Ngamassi et al. 2020), for the purpose of this study, we examined underserved communities through the lens of a minority group, specifically African Americans in southeast Texas. Previous studies have indicated that minority groups are more vulnerable during disasters (Baker 2011; Ramakrishnan et al. 2019; Ngamassi et al. 2020). Similarly, studies have shown that disasters such as the 2005 Hurricane Katrina floods, 2012 Hurricane Sandy, and 2013 Winter Storm Nemo had a greater impact on African-American communities compared to other demographics (Klinenberg 2013; Squires 2017). Thus, the scope of this study was to understand the use of social media by underserved communities, that is, in this case African-American communities, for disaster management.

Even though there are competing theories such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) that can shed light on the use of technology, the focus of these models is chiefly restricted to the use of technology. Given the ubiquitous nature of social media, the use of social media may not be as big a concern as the behavior that motivates people to use social media for a specific purpose, that is, for disaster management. In this study, we sought to examine the use of specific information and communication technology (social media) by a specific underserved community (African Americans in southeast Texas) to cope with an unexpected and undesirable event (disaster).

The two main characteristics of disasters are that they are negative and unexpected. The premise of attribution theory lies in understanding how individuals behave when faced with an unpredictable undesirable outcome (Weiner 1985). There are three stages of attribution—in the first stage, a person observes a certain behavior; in the second stage, the observer believes the behavior to be intentional; and in the third stage, the behavior is attributed either to the person or to the situation (Weiner 1986). Following this analogy, we examined the behavior as the use of social media for disaster management and the situation as the mitigation of disaster risks. Thus, if an underserved community attributes the success in mitigating the risks of disasters to the use of social media, then they may be inclined to use social media for disaster management. Therefore, examining the use of social media for disaster management by an underserved community through the lens of attribution theory provides us with insights into the behavior that drives people within the underserved community to use social media for disaster management, and into what can further help to motivate people to use social media for disaster management. Against this backdrop, we chose to examine the intention to use social media through the lens of attribution theory.

2.1 The Digital Divide

Digital divide refers to the gap that exists between those who have access to information and communication technologies (ICT) and those who do not have access to these technologies (van Dijk 2006; Xiao et al. 2015). In the 1990s, the concept of the digital divide was introduced when researchers wanted to explain the difference between the have and have-nots with respect to using or not using the Internet and computers (Bach et al. 2013). Initial research in the area of the digital divide focused on the infrastructure required for using the Internet and computers and the affordability and the availability of the Internet and computers (Brazilai-Nahon 2006; van Dijk 2006). Later research in this area evolved in exploring the digital divide by examining the ICT market and sector development, ICT penetration and household usage, usage of ICT by enterprises and government, and the development of ICT education (Cilan et al. 2009; Bach et al. 2013). Other studies used the digital divide to understand the demographic, economic, and social characteristics of the ICT users and to understand the socioeconomic differences concerning the use of ICT (Mason and Hacker 2003; Barzilai-Nahon 2006; Vehovar et al. 2006; Vu 2011; Zoroja 2011; Bach et al. 2013).

We extended this notion of the digital divide to understanding the use of social media, which are emerging as popular ICT (White 2012; Xiao et al. 2015) for disaster management. Prior studies have indicated that the involvement in social media usage during disasters is uneven across different social groups (Austin et al. 2012; Li et al. 2013; Xiao et al. 2015). Well-educated people in the areas of arts, business, management, and science tend to be more involved in the use of social media (Li et al. 2013) compared to underserved communities. Reports regarding the underserved communities suffering disproportionately more compared to other communities during natural hazard-related disasters such as Katrina, Sandy, and Nemo, even with the broadcasting of required and relevant information for safety precautions (Klinenberg 2013; Squires 2017) may be an indicator of a lack of effective use of social media. Given the penetration power of social media, access to social media may not be as big an issue as the proper utilization of social media for managing disasters. In recent years, with information and communication technologies becoming ubiquitous, the focus of the digital divide has shifted to the usage of technology rather than the availability or affordability (van Deursen and van Dijk 2014). Thus, using social media for a specific purpose such as disaster management may require a broad range of skills such as sifting or navigating through lots of information, determining relevant information, and acting upon this information. The first step towards resolving a problem is recognizing the existence of the problem. Thus, rather than access to social media, individuals in underserved communities may lack the skills required for using social media effectively to manage disasters. Therefore, we hypothesized that:

H1: The digital divide influences the use of social media for disaster management such that there exists a negative relationship between underserved communities and their use of social media for disaster management.

2.2 Attribution Theory

Attribution is a psychological variable that examines the cognitive process through which an individual deduces the reason for the behavior of others (Calder and Burnkrant 1977; Hughes and Gibson 1987). Research on attribution theory mainly focuses on individuals’ perceived causation, that is, what is the cause of behavior, and this interpretation regarding the cause of behavior further determines their reaction to that behavior (Calder and Burnkrant 1977; Kelley and Michela 1980). Other studies have extended this theory beyond just understanding the behavior of individuals to linking causes to outcomes and events that an individual experiences (Swanson and Kelley 2001; Ngamassi et al. 2016b). Predicting and controlling events and outcomes by understanding, organizing, and forming meaningful perspectives is one of the main aims of the attributional process. This inclination towards attempting to control outcomes is more apparent in the case of unexpected situations such as disasters (Ngamassi et al. 2016b).

One of the early studies that used attribution theory in understanding communication behavior included examining communication strategies for product harm crises (Siomkos and Kurzbard 1994). Another study conducted by Coombs and Holladay (1996) examined the different strategies that organizations use to address different crises using attribution theory. Similarly, Jeong (2009) used attribution theory to explain peoples’ response to an organization that caused an oil spill accident. Ngamassi et al. (2016b) used attribution theory to provide a framework that explains the scarcity in communication during the preparedness and mitigation phase of disaster management. These studies indicated that given the negative and unpredictable nature of disasters, attribution theory would provide a good lens to understand disaster management. However, there still is a dearth of research that can provide a comprehensive framework for understanding communication and information exchange using social media during disasters.

In this study, we drew on the Weiner model of achievement attributions to understand the use of social media for managing disasters by underserved communities. This model classifies the attributional factors into the three causal dimensions of locus, stability, and controllability (Weiner 1986; Graham 1991; Savolainen 2013). The dimension of locus examines the attributional factors in terms of location, whether it is internal or external to an individual. Thus, the individual may attribute his or her success or failure in the use of social media for disaster management to factors that originate within themselves or to factors that are external to the individual.

The stability dimension describes the attributional factors as constant, indicating the causes are stable and permanent, or as varying over time, indicating the causes are unstable and can change. Thus, the individual may examine the reasons for the successful use of social media in disaster management as to whether they are stable or unstable. If the individual perceives the reasons of successful use to be stable, then the outcome can easily be replicated for different occasions and scenarios. However, if the individual perceives the reason to be unstable, that is, it changes with the passing of time, then the individual may be inclined to believe the successful use of social media for disaster management to be a one-time success and may not be inclined to use social media for future disaster management as the outcome may not be reliable.

Finally, the dimension of controllability examines the control that the individual has over the attributional factors (Graham 1991; Ngamassi et al. 2016b). Thus, the individual may exert control over his or her use of social media. However, he or she will not have any control over how the disaster is managed. In this study, based on these three dimensions, we examined the impact of attributional factors—ability, effort, and task difficulty—on the use of social media for disaster management by underserved communities.

In this study, “ability” refers to the capability of the individual to handle a specific technology for a specific task. Weiner (1986) categorized ability as highly stable and internal. Thus, ability is the perception of the individual regarding how good he/she is and this perception is permanent and will not vary with time. Individuals may not have a lot of control over their perception of ability (Ngamassi et al. 2016b). Given the ubiquitous nature of social media and the affordability of mobile devices for accessing social media (van Deursen and van Dijk 2014), the general perception regarding the ability for using social media should be high in all communities, including underserved communities. Thus, if the individuals perceive that they have a clear understanding of how social media work for disaster management, they will be more inclined to use social media for disaster management. Similarly, if the individuals perceive that using social media for disaster management comes naturally to them, they will be more motivated to use social media for disaster management. If individuals have a high perception regarding their ability to utilize social media for disaster management, they will be more disposed to using social media for managing disasters. Therefore, we hypothesized that:

H2: There exists a positive relationship between attributions of ability and the intention to use social media for disaster management.

We defined “effort” in this study as the amount of time and resources an individual is willing to spend in understanding the use of social media for managing disasters. Weiner (1986) categorized effort as an internal attribution that is unstable and controllable. Thus, the amount of time and resources the individual chooses to spend in understanding and perfecting the use of a specific technology for a specific purpose is within the individual’s control. The effort that individuals put in regarding the use of technology may also vary. The ubiquity of social media ensures that the access to these platforms is available to individuals belonging to all communities (van Deursen and van Dijk 2014). Thus, if an individual works hard to learn the different nuances of using social media for effectively using them for disaster management, he/she may be more inclined to use social media for disaster management. Therefore, we hypothesized that:

H3: There exists a positive relationship between attributions of effort and the intention to use social media for disaster management.

We defined “task difficulty” as the level of difficulty an individual faces for performing the given tasks. Weiner (1986) classified task difficulty as an external attribution that is stable. The difficulty of certain tasks may be given and the individual may not have control over the level of difficulty of the task he/she is asked to perform (Weiner 1986). Thus, if the task of managing disasters using social media is not perceived as simple, then the individual is not likely to use social media for disaster management. Similarly, if an individual feels that he/she tends to make more mistakes while using social media for disaster management, the inclination to use social media for disaster management goes down. If individuals perceive data entry or information gathering to be difficult using social media for managing disasters, their intention to use social media for disaster management goes down. Thus, if task difficulty in using social media for disaster management rises, the intention to use social media for disaster management goes down. Therefore, we hypothesized that:

H4: There exists a negative relationship between attributions of task difficulty and the intention to use social media for disaster management.

Finally, we also examined the moderating impact of being part of an underserved community on the relationship between task difficulty and the intention to use social media for disaster management. Unlike effort and ability, task difficulty has external attribution (Weiner 1985). Thus, a task that an individual perceives to be difficult may be perceived as simple by a different individual. Prior studies have shown that there exists a gap between different socioeconomic groups in terms of completion of online tasks or the time taken to complete specific online tasks (Hargittai 2002). Given the differentiated digital literacy when it comes to navigating the Internet (Mossberger et al. 2003; Bunz 2004; Hargittai and Walejko 2008), online tasks may be perceived as difficult by underserved communities. Extending this to the use of social media for disaster management, individuals from underserved communities may perceive similar tasks to be more difficult. Thus, the negative influence of task difficulty will be more pronounced for underserved communities. Therefore, we hypothesized that:

H5: Being part of an underserved community will moderate the relationship between task difficulty and intention to use social media for disaster management such that the relationship will be stronger for underserved communities.

3 Methodology

We used survey methodology and a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach in this study. The items for measuring constructs related to ability (A), effort (E), and task difficulty (TD) were adapted from Henry and Stone (2001) and revised to suit the context of our study. The survey items used to measure “ability” included:

A1: I have a clear understanding of how social media work for disaster management;

A2: Using social media for disaster management comes naturally to me; and

A3: I have the ability to use social media for disaster management.

The survey items used to measure “effort” included:

E1: I work very hard to learn how to use social media for disaster management;

E2: I spend a lot of time to ensure I use social media correctly for disaster management; and

E3: I spend a lot of time at work learning to use social media for disaster management.

The survey items used to measure “task difficulty” were reverse coded and included:

TD1: Most of the tasks I perform with regard to disaster management using social media are quite simple;

TD2: Social media for disaster management work in such a way that mistakes are not easily made;

TD3: Information gathering is easy to make using social media; and

TD4: Social media are easy to use for disaster management.

The survey items used to measure “intention to use (IU) social media (SM) for disaster management” were adapted from the Technology Acceptance Model literature and contextualized to suit our study. The survey items included:

SM IU1: I intend to use social media for disaster management;

SM IU2: I would use social media for disaster management;

SM IU3: I plan to use social media for disaster management; and

SM IU4: I expect to use social media for disaster management.

The survey items were adapted from previously validated survey instruments and contextualized to suit our study. We carried out reliability and validity tests for these survey items. The details of the tests and results are provided in Sect. 4.1. A five-point Likert scale with 1 indicating “strongly disagree” and 5 indicating “strongly agree” was used to measure the survey items. A convenience sampling was used to collect the data for this study.

4 Data Analysis and Results

The survey was sent to 160 people in underserved communities (predominantly African-American communities) in southeast Texas in November 2019. Of the 160 survey recipients, 124 people completed and returned the survey, and the responses were useful. The response rate was around 78% (77.5%). Of the 124 respondents who participated and completed the survey, 56 (45.2%) were male and 68 (54.8%) were female; 81% of the respondents were of African American origin, 6% were white, and the rest (13%) consisted of Hispanic or Latino, Asian, American Indian, and Native Hawaiian origins. The majority (62.9%) of the respondents had completed high school or some college education, and 58.9% of the respondents made less than USD 35,000 a year. The majority (63%) of the respondents were renters. Only 18.5% of the respondents were homeowners, and the remaining 18.5% chose not to answer this question. This indicates that the majority of the people living in these communities are low-income people. About 82% of the respondents were between the age range of 18 and 34, 12% were between 35 and 55, and the remaining (6%) were above 55 years. With regard to work experience, the majority (60.2%) of the respondents had less than five years of work experience. As to disaster experience, 58.9% of the respondents sought out help from others such as friends, relatives, and neighbors, 10.5% did not seek help, 6.5% did not receive any help, 23.4% did not consider themselves victims although they did experience a disaster, and 0.8% chose not to answer this question.

We used partial least squares (PLS), a structural equation modeling (SEM) technique, to validate the model. The PLS method is a data analysis technique for evaluating theoretical relationships between systems of variables (Willaby et al. 2015). Studies in the fields of accounting, information systems, marketing, and strategic management have used PLS extensively for data analyses (Lee et al. 2011; Hair Jr et al. 2012; Willaby et al. 2015; Jacob and Darmawan 2018; Rahman et al. 2020). The PLS method offers the assessment for two models: (1) the measurement model; and (2) the structural model. The measurement model describes the relationship of measured variables to their own latent variables or the theoretical constructs. This is done by evaluating the reliability and validity of measures. The structural model examines the relationship between the theoretical constructs (Ramakrishnan et al. 2012). The PLS method offers several advantages. It makes no assumption about data normality and evaluates a measurement model. Another advantage concerns the requirement of small sample size. The commonly used heuristic to derive adequate sample size for using PLS is 10 times the largest number of structural paths directed at a particular construct in the structural model. This model has no more than five paths influencing a single dependent construct. Therefore, the sample size of 124 is more than adequate for the use of the PLS method in this study.

4.1 Assessment of the Measurement Model

All the constructs used in this study are reflective in nature. We examined the internal consistency and reliability of the constructs by evaluating composite reliability scores and Cronbach’s alpha (Table 1). A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.7 or above and a composite reliability score of 0.7 or above is considered a satisfactory indicator of internal consistency (Ramakrishnan et al. 2012; Hair Jr et al. 2018). All the constructs exhibited adequate reliability with satisfactory composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha greater than 0.7.

We evaluated convergent validity of the constructs by assessing the outer loadings and the average variance extracted (AVE). The outer loadings examine how well the observed variable describes the construct to which it is related (Tenenhaus et al. 2005). The observed variables are the indicators or the survey items in the survey questionnaire. For example, in Table 2, A1, A2, and A3 represent the three items in the survey questionnaire used to measure the construct “ability”; E1, E2, and E3 are the items used to measure the construct “effort”; TD1, TD2, TD3, and TD4 are the survey items used to measure the construct “task difficulty”; and SM IU1, SM IU2, SM IU3, and SM IU4 are the survey questions used to measure “intention to use social media.” Loadings of all the retained indicators were greater than the recommended threshold of 0.7 and were significant at 0.01 level (see Table 2). The AVE refers to the variance explained by the indicators of the construct relative to the variance due to the measurement error (Chin 1998; Ramakrishnan et al. 2012). A satisfactory model must have an AVE score greater than 0.5 (Komiak and Benbasat 2006; Ramakrishnan et al. 2012). The AVE scores of all the constructs were greater than the recommended threshold of 0.5 (see Table 1) suggesting our constructs exhibit adequate construct validity.

Discriminant validity of the constructs was evaluated through the Fornell-Lacker criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT). Adequate discriminant validity confirms that the construct measure is empirically unique and other measures within the structural equation model do not capture this specific construct of interest (Henseler et al. 2015; Hair Jr et al. 2018). In order to exhibit adequate discriminant validity, according to the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the correlations between the constructs should be less than the square root of the AVE of the individual construct (Hair Jr et al. 2018). The correlations among the constructs were less than the square root of the AVEs of the individual construct (Table 3), thus adhering to the discriminant validity requirement as per the Fornell-Lacker criterion. According to the HTMT criterion, for the constructs to exhibit adequate discriminant validity, the value of the HTMT correlations between the constructs should be less than 0.9 (Henseler et al. 2015). The HTMT values for all our constructs were below the threshold of 0.9, thus suggesting adequate discriminant validity (Table 4).

4.2 Assessment of the Structural Model

The structural model examines the relationships between theoretical constructs. We evaluated the structural model by applying the bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping procedure with replacement using 5000 subsamples. We tested the hypotheses using a one-tailed t-test for unidirectional hypotheses through SmartPLS3.0 (Hair Jr et al. 2018). Prior studies have indicated that income may play a role in the digital divide. Therefore, we controlled for income in the model. Previous studies have shown that work experience and age may play a role in the usage of social media. Therefore, we also controlled for age and work experience in this study.

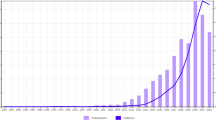

The results of the study indicate that underserved community has a negative relationship with intention to use social media for disaster management (β = −0.681, t = 1.979, p < 0.05), supporting the digital divide and intention to use social media hypothesis (H1). Effort has a positive relationship with intention to use social media for disaster management (β = 0.425, t = 3.372, p < 0.01), supporting the effort and intention to use social media hypothesis (H3). Task difficulty has a negative relationship with intention to use social media for disaster management (β = −0.460, t = 1.490, p < 0.1), supporting the task difficulty and intention to use social media hypothesis (H4). Further, underserved community in conjunction with task difficulty has a positive relationship with intention to use social media for disaster management (β = 0.58, t = 1.687, p < 0.05), supporting underserved community × task difficulty and intention to use social media hypothesis (H5), albeit in the opposite direction (Fig. 3). Interestingly, we did not find support for H2, the relationship between ability and intention to use social media for disaster management. The results of our test are provided in Fig. 2 and Table 5.

Overall, this model explains about 22% (R2 = 0.221) of the variance in the “intention to use social media for disaster management.” We conducted a Harmon’s one-factor test (Podsakoff and Organ 1986) by entering all the variables into an exploratory factor analysis. This was done to check whether there exists the threat of common method bias. The factor accounted for less than 40% of the variance, suggesting that common method bias is not a problem in this study. We also checked for the threat of multicollinearity in our model by assessing the variation inflation factor (VIF). The VIFs for all the independent variables were less than 3.3, suggesting multicollinearity is not a concern in this model.

5 Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the propensity of media use by underserved communities and explore the factors that can influence the use of social media for disaster management. The results indicate that the propensity of using social media for disaster management is low for underserved communities. This is in line with prior research on the digital divide. Prior studies examined the digital divide in terms of access and affordability of technology, and the results indicated that the accessibility and affordability for underserved communities is significantly lower than that for other better served communities (van Dijk 2006; van Deursen and van Dijk 2014). The results of this study are also in line with the results of prior studies with regard to the use of technology. Thus, in this digital age, the ubiquitous nature of technologies like social media may make these platforms easily available to everyone. However, usage of these tools for the betterment of peoples’ situations such as using social media to get relevant information about disasters to take precautionary action may still be a challenge for underserved communities.

The study results also indicate that there exists a positive relationship between an individual’s effort and the intention to use social media for disaster management, and a negative relationship between task difficulty and the intention to use social media for disaster management. These results are consistent with the results of prior studies that view performance through the lens of attribution theory and stated that increased efforts lead to improved performance and increased task difficulty leads to a decline in performance (Weiner 1985; Graham 1991). Our results are also consistent with prior studies that examined information systems use in general using the attribution theory. Prior studies have shown individual ability and effort to be positively related to computer self-efficacy, whereas task difficulty to have a negative relationship with computer self-efficacy (Henry and Stone 2001). Thus, the study results indicate that attribution theory holds true for the use of social media in disaster management. When individuals put in more effort to understand social media use for managing disasters, they are more inclined to use social media for disaster management. Similarly, if individuals perceive the task of using social media for disaster management as difficult, their motivation to use social media for managing disasters goes down. However, surprisingly, we did not find support for the relationship between ability and intention to use social media for disaster management. Given the pervasive nature of social media, the respondents in our study may have been very familiar with the use of social media and would have perceived themselves to have high ability in using social media. Thus, whether they have the ability to use social media for disaster management may not be a critical factor for them.

Furthermore, the study results indicate that being part of the underserved community has a moderating impact on the relationship between task difficulty and the intention to use social media for disaster management. However, interestingly, the direction of this moderating impact is the opposite of the direction suggested in our hypothesis.

On closer examination, we found that for people belonging to the underserved community in our case study at the lower level of task difficulty, the intention to use social media is low; however, as the perception regarding the task difficulty increases, the intention to use social media also increases (Fig. 3). This seems counterintuitive, especially, when prior studies have shown that with the increase in difficulty level the inclination to use the specific technology declines (Hughes and Gibson 1987; Jeong 2009). One of the probable explanations for low motivation for completing tasks with low difficulty level using social media is that people may find the tasks too simple for them to warrant the use of social media. Probable explanations for an increase in motivation to use social media for disaster management is the fact that the people in underserved communities have been victims and have suffered inequitably during disasters (Deacon 2018). When they realize that there is a communication tool available that can help them safeguard themselves from potential hazards and disasters, they would want to utilize the tool to keep them safe. Another explanation is that the majority of the respondents who took part in the study had completed some college, or had a higher degree. Therefore, they realize the importance of the role that social media play in disaster management and are willing to use social media to keep themselves safe during the occurrence of disasters even though they may perceive them to be difficult to use. However, this result should be viewed keeping in mind that most of the data in the sample pertain to African-American communities in southeast Texas.

6 Implications for Theory

The theoretical implications of this study are significant. Prior studies emphasized the importance of the digital divide and examined the digital divide from the perspective of accessibility and affordability of technology (Blank and Reisdorf 2012; Bach et al. 2013). There are few studies that focus on the digital divide with regard to the usage of technology (van Deursen and van Dijk 2014), and there is a dearth of studies that examine the use of ubiquitous platforms for a specific purpose through the lens of the digital divide. The results of this study suggest that although social media have permeated all communities and there is not much gap regarding the affordability or the usage of ubiquitous platforms (Constine 2013), underserved communities still lack the motivation to use such a platform for a specific purpose such as disaster management. This is a major contribution of this study to the field of ICT in the area of disaster management.

Second, we examined the factors that can influence the use of social media for disaster management through the lens of attribution theory. Although previous studies have emphasized the importance of understanding disaster management through the use of attribution theory (Coombs 2007), there is a dearth of studies that examine the role of technology in disaster management using attribution theory. Prior studies that investigated the role of social media in disaster management using attribution theory just provided a framework or model (Ngamassi et al. 2016b). There are not many studies that develop a comprehensive model using attribution theory and the digital divide and empirically test that model for understanding the use of social media in disaster management. In this study, we show that prior results from attribution theory also conform to results on the role of social media in disaster management with respect to underserved communities. This is the second and more distinguishing contribution in the field of ICT and disaster management.

7 Implications for Practice

This study provides a number of significant practical implications. First, the results of this study indicate that having access to or being able to afford technology does not mean that technology is being used effectively. Thus, government agencies and organizations charged with disseminating information through social media for preventing disaster-related casualties should ensure that the underserved population in a community is aware of how to use social media for accessing that information.

Second, the study results indicate that with increased effort and reduced task difficulty, individuals tend to use social media for disaster management. Therefore, disaster management organizations should encourage underserved communities to use social media for disaster management by providing instructions in the use of social media for disaster management such that the tasks required are simple. Finally, the results indicate that even though underserved communities may perceive the task of using social media for disaster management as difficult, they do prefer to use these platforms for communication and information exchange during disasters. Therefore, government agencies and disaster management organizations should motivate individuals in underserved communities to use social media for disaster management by providing them with skill sets and education.

8 Limitations and Future Research

Although the data support our hypothesized model, the findings of this study must be examined in light of its limitations. These limitations can also provide the starting point for future research. A convenience sampling method was used to collect data. Our data were collected in southeast Texas. Although the analyses of data collected through convenience sampling boost the internal validity of the study, additional studies are required to conclude the generalizability of this study. Second, the data used in this study are cross-sectional, and additional studies are required to evaluate and establish causality. Third, we examined the digital divide in terms of underserved communities from southeast Texas. Therefore, additional studies are required to examine different socioeconomic factors to test the model.

9 Conclusion

This study suggests that there is a gap between underserved communities and other better served communities in the use of social media for disaster management. It is important that special attention is given to the development of the social media skills of the people living in these communities so they can use social media tools effectively and efficiently before, during, and after disasters. The development of such skills is even more important given that disaster management organizations and agencies have been increasingly using social media tools such as Facebook and Twitter before, during, and after disasters. This study proposes a model to understand the communication behavior in the use of social media for disaster management by underserved communities. The model is developed by examining the literature on the digital divide and attribution theory and validated using data from southeast Texas in the United States. The findings of this study contribute to the evolving information systems literature focusing on the area of information and communications technology and disaster management.

References

Adekola, J., D. Fischbacher-Smith, and M. Fischbacher-Smith. 2020. Inherent complexities of a multi-stakeholder approach to building community resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 11(1): 32–45.

Austin, L., B.F. Liu, and Y. Jin. 2012. How audiences seek out crisis information: Exploring the social-mediated crisis communication model. Journal of Applied Communication Research 40(2): 188–207.

Bach, M.P., J. Zoroja, and V.B. Vukic. 2013. Determinants of firms’ digital divide: A review of recent research. Procedia Technology 9: 120–128.

Baker, E.J. 2011. Household preparedness for the aftermath of hurricanes in Florida. Applied Geography 31(1): 46–52.

Berchtold, C., M. Vollmer, P. Sendrowski, F. Neisser, L. Muller, and G. Sonja. 2020. Barriers and facilitators in interorganizational disaster response: Identifying examples across Europe. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 11(1): 46–58.

Blank, G., and B.C. Reisdorf. 2012. The participatory web. Information, Communication, and Society 15(4): 537–554.

Brazilai-Nahon, K. 2006. Gaps and bits: Conceptualizing measurement for digital divide/s. The Information Society 22(5): 269–278.

Bunz, U. 2004. The Computer-Email-Web (CEW) fluency scale development and validation. International Journal of Human Computer Interaction 17(4): 479–506.

Calder, B.J., and R.E. Burnkrant. 1977. Interpersonal influence on consumer behavior: An attribution theory approach. Journal of Consumer Research 4: 29–37.

Chin, W.W. 1998. Issues and opinions on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly 22(1): vi–xvi.

Cilan, C.A., B.A. Bolat, and E. Cosku. 2009. Analyzing digital divide within and between member and candidate countries of European Union. Government Information Quarterly 26(1): 98–105.

Constine, J. 2013. Facebook reveals 78% of US users are mobile as it starts sharing user counts by country. https://techcrunch.com/2013/08/13/facebook-mobile-user-count/. Accessed 16 Jul 2019.

Coombs, W.T. 2007. Attribution theory as a guide for post-crisis communication research. Public Relations Review 33(2): 135–139.

Coombs, W.T., and S.J. Holladay. 1996. Communications and attributions in a crisis: An experimental study in crisis communication. Journal of Public Relations Research 8(4): 279–295.

Deacon, B. 2018. Emergency announcements alone during disasters not reliable in saving lives. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-01-06/emergency-announcements-alone-during-disasters-not-reliable/9304666. Accessed 17 Jul 2019.

Dennis, L., L. Palen, and J. Anderson. 2014. Mastering social media: An analysis of Jefferson County’s communications during the 2013 Colorado Floods. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management (ISCRAM), 18–21 May 2014, University Park, Pennsylvania.

Graham, S. 1991. A review of attribution theory in achievement context. Educational Psychology Review 3(1): 5–38.

Hair, J.F., Jr., W.C. Black, B.J. Babin, and R.E. Anderson. 2018. Multivariate data analysis. Eaglewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Hair, J.F., Jr., G.T.M. Hult, C.M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2016. A primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hair, J.F., Jr., M. Sarstedt, C.M. Ringle, and J.A. Mena. 2012. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40(3): 414–433.

Hargittai, E. 2002. Second level digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills. First Monday 7(4). https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/942/864. Accessed 23 Jul 2019.

Hargittai, E., and G. Walejko. 2008. The participation divide: Content creation and sharing in the digital age. Information, Communication & Society 11(2): 239–256.

Henry, J.W., and R.W. Stone. 2001. The role of computer self-efficacy, outcome expectancy, and attribution theory in impacting computer system use. Journal of International Information Management 10(1): 1–16.

Henseler, J., C.M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2015. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43(1): 115–135.

Hiltz, S., J. Kushma, and L. Plotnick. 2014. Use of social media by U.S. public sector emergency managers: Barriers and wish lists. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management (ISCRAM), 18–21 May 2014, University Park, Pennsylvania.

Houston, J.B., J. Hawthorne, M.F. Perreault, E.H. Park, M.G. Hode, M.R. Halliwell, S.E.T. McGowen, and R. Davis et al. 2014. Social media and disasters: A functional framework for social media use in disaster planning, response, and research. Disasters 39(1): 1–22.

Hughes, C.T., and M.L. Gibson. 1987. An attribution model of Decision Support Systems (DSS) usage. Information and Management 13(3): 119–124.

Jacob, D.W., and I. Darmawan. 2018. Extending the UTAUT model to understand the citizens’ acceptance and use of electronic government in developing country: A structural equation modeling approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Enterprise and System Engineering, 21–22 November 2018, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 92−96.

Jeong, S. 2009. Public’s responses to an oil spill accident: A test of the attribution theory and situational crisis communication theory. Public Relations Review 35(3): 307–309.

Karanasios, S., V. Cooper, M.P. Balcell, and P. Hayes. 2019. Inter-organizational collaboration, information flows, and the use of social media during disasters: A focus on vulnerable communities. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences, 8–11 January 2019, Maui, Hawaii, 2995−3004.

Karaye, I.M., C. Thompson, and J.A. Horney. 2019. Evacuation shelter deficits for socially vulnerable Texas residents during Hurricane Harvey. Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology 6: 1–7.

Kelley, H.H., and J.L. Michela. 1980. Attribution theory and research. Annual Review of Psychology 31: 457–501.

Klinenberg, E. 2013. The digital divide in emergency management. Qualcomm Incorporated. https://www.qualcomm.com/news/onq/2013/03/01/digital-divide-emergency-management. Accessed 18 Jul 2019.

Komiak, S.Y.X., and I. Benbasat. 2006. The effects of personalization and familiarity on trust and adoption of recommendation agents. MIS Quarterly 30(4): 941–960.

Lee, L., S. Petter, D. Fayard, and S. Robinson. 2011. On the use of partial least squares path modeling in accounting research. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 12(4): 305–328.

Li, L., M.F. Goodchild, and B. Xu. 2013. Spatial, temporal, and socioeconomic patterns in the use of Twitter and Flickr. Cartography and Geographic Information Science 40(2): 61–77.

Marlowe, J., A. Neef, C.R. Tevaga, and C. Tevaga. 2018. A new guiding framework for engaging diverse populations in disaster risk reduction: Research, relevance, receptiveness, and relationships. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 9(4): 507–518.

Mason, S.M., and K.L. Hacker. 2003. Applying communication theory to digital divide research. IT & Society 1(5): 40–55.

McCallum, I., W. Liu, L. See, R. Mechler, A. Keating, S. Hochrainer-Stigler, J. Mochizki, and S. Fritz et al. 2016. Technologies to support community flood disaster risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 7(2): 111–122.

McCormick, S. 2016. New tools for emergency managers: An assessment of obstacles to use and implementation. Disasters 40(2): 207–225.

Moreira, F., M.J. Ferreira, C.P. Santos, and N. Durão. 2017. Evolution and use of mobile devices in higher education: A case study in Portuguese higher education institutions between 2009/2010 and 2014/2015. Telematics and Informatics 34(6): 838–852.

Mossberger, K., C.J. Tolbert, and M. Stansbury. 2003. Virtual inequality: Beyond the digital divide. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Ngamassi, L., T. Ramakrishnan, S. Rahman, and H. Rose. 2014. Social media technology for crisis management. In Proceedings of the DSI 2014 Annual Meeting, 22–25 November 2014, Tampa, Florida.

Ngamassi, L., T. Ramakrishnan, and S. Rahman. 2016. Use of social media for disaster management: A prescriptive framework. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing 28(3): 122–140.

Ngamassi, L., T. Ramakrishnan, and S. Rahman. 2016b. Examining the role of social media in disaster management from an attribution theory perspective. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management (ISCRAM), 22–25 May 2016b, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil.

Ngamassi, L., T. Ramakrishnan, and S. Rahman. 2020. Investigating the use of social media by underserved communities for disaster management. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management (ISCRAM), May 2020, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 490−496.

Palen, L. 2008. Online social media in crisis events. EDUCAUSE Quarterly 31(3): 76–78.

Podsakoff, P.M., and D.W. Organ. 1986. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management 12(4): 531–544.

Rahman, S., T. Ramakrishnan, and L. Ngamassi. 2020. Impact of social media use on student satisfaction in higher education. Higher Education Quarterly 74(3): 304–319.

Ramakrishnan, T., M.C. Jones, and A. Sidorova. 2012. Factors influencing business intelligence (BI) data collection strategies: An empirical investigation. Decision Support Systems 52: 486–496.

Ramakrishnan, T., L. Ngamassi, and S. Rahman. 2019. Social media in disaster management: Exploring the information exchange behavior in the underserved communities. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management (ISCRAM), 19–22 May 2019, Valencia, Spain, 1407−1408.

Reynolds, B., and M. Seeger. 2012. Crisis and emergency risk communication, 2012th edn. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Savolainen, R. 2013. Approaching the motivators for information seeking: The viewpoint of attribution theories. Library & Information Science Research 35(1): 63–68.

Siomkos, G.J., and G. Kurzbard. 1994. The hidden crisis in product-harm crisis management. European Journal of Marketing 28(2): 30–41.

Squires, G.D. 2017. Harvey is not a natural disaster. The American Prospect. https://prospect.org/article/harvey-not-natural-disaster. Accessed 10 Jun 2019.

Swanson, S.R., and S.W. Kelly. 2001. Attributions and outcomes of the service recovery process. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 9(4): 50–65.

Tenenhaus, M., V.E. Vinzi, Y.M. Chatelin, and C. Lauro. 2005. PLS path modeling. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 48(1): 159–205.

van Deursen, A.J.A.M., and J.A.G.M. van Dijk. 2014. The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. New Media & Society 16(3): 507–526.

van Dijk, J.A.G.M. 2006. Digital divide research, achievements, and shortcomings. Poetics 34(s4–5): 221–235.

Vehovar, V., P. Sicherl, T. Husing, and V. Dolnical. 2006. Methodological challenges of digital divide measurements. The Information Society 22(5): 79–290.

Vu, K.M. 2011. ICT as a source of economic growth in the information age: Empirical evidence from the 1996–2005 period. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity 1(1): 49–55.

Weiner, B. 1985. An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychology Review 92(4): 548.

Weiner, B. 1986. An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. New York: Springer-Verlag.

White, C.M. 2012. Social media, crisis communication, and emergency management: Leveraging Web 2.0 technologies. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Willaby, H.W., D.S.J. Costa, B.D. Burns, C. MacCann, and R.D. Roberts. 2015. Testing complex models with small sample sizes: A historical overview and empirical demonstration of what Partial Least Squares (PLS) can offer differential psychology. Personality and Individual Differences 84: 73–78.

Xiao, Y., Q. Huang, and K. Wu. 2015. Understanding social media data for disaster management. Natural Hazards 79(3): 1663–1679.

Yates, D., and S. Paquette. 2011. Emergency knowledge management and social media technologies: A case study of the 2010 Haitian Earthquake. International Journal of Information Management 31(6): 6–13.

Zoroja, J. 2011. Internet, e-commerce, and e-government: Measuring the gap between European developed and post-communist countries. Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems 9(2): 119–133.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Department of Homeland Security, grant # 2017‐ST‐062‐000005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramakrishnan, T., Ngamassi, L. & Rahman, S. Examining the Factors that Influence the Use of Social Media for Disaster Management by Underserved Communities. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 13, 52–65 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-022-00399-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-022-00399-1