Abstract

This article examines how risk is communicated by different actors, particularly local print newspapers and actors at the community level, in two different geographical contexts that are severely affected by wildfires—the Brazilian Amazon and Atlantic Spain. We analyzed how wildfire risk is framed in local print media and local actor discourse to elucidate how wildfire risk is interpreted and aimed to identify the main priorities of these risk governance systems. The main findings reveal that the presentation of wildfire as a spectacle is a serious obstacle to the promotion of coherent risk governance and social learning, which involves recognizing wildfire risk as a social, political, economic, and environmental problem. Proactive risk governance should communicate the multifaceted nature of risk and stimulate dialogue and negotiation among all actors to build consensus regarding land use and the creation of risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A critical component of risk governance is communication, which plays a critical role in terms of framing risk and facilitating social consensus about risk construction and distribution. Risk communication involves a wide range of actors and channels, from emergency warnings issued by official channels to less formal messages via traditional sources (for example, newspaper, television, and radio) or social media (for example, Twitter and Facebook). Because societal actors are both receptors and disseminators of disaster risk information (Morss et al. 2017), understanding the way disaster risk is communicated in different governance systems is essential for identifying how societies frame risk.

Communication is essential during emergency response (Sutton et al. 2008; Tang et al. 2015; Matlock et al. 2017), but its role is equally important in other processes related to risk governance (Fra.Paleo 2015a). There are numerous contextual factors that influence people’s access to information, their interpretation of risk, and their capacity to take action (Morss et al. 2017). Risk communication is a complex activity that involves mutual interactions and a shared sense of common understanding (Renn 2014). Thus, the development of instruments to engage societal actors in the exchange of data, information, and perspectives to support decision making about risk is essential when developing new approaches to risk communication and risk governance (Fra.Paleo 2015b). Renn (2014) highlighted the need for strong risk communication practices to provide the affected parties with the insight needed to make informed decisions or judgments that reflect the best available knowledge as well as their own preferences. However, the attributes of risk communication processes that contribute to incoherent risk governance are not obvious. To better understand these features, this article examines how risk is communicated by different actors, particularly local print newspapers and actors at the community level, in two different geographical contexts that are severely affected by wildfires, the Brazilian Amazon and Atlantic Spain.

2 Literature Review

In this section we provide a brief theoretical background on this topic. In the first place we examine the debate on the evolution of the forms of risk communication and then we present an overview of the role of media in shaping the discourse on wildfire risk.

2.1 Main Forms of Risk Communication

Three forms of risk communication have been identified: one-way communication, two-way communication, and social learning. In the one-way communication approach, information is conveyed by experts and governments to lay citizens to educate the citizens about risk. Experts are considered the legitimate actors to conduct a risk analysis, while the public is a passive agent whose level of ignorance regarding risks must be decreased (De Marchi 2015). Two-way communication provides the public with an opportunity to share feedback. This process may induce a transition from a public misperception (deficit model) to an appreciation of the public reaction to risk (communication model) and near-instantaneous feedback. The two-way form of communication is able to clarify and adapt the diffusion of disaster information (Sood et al. 1987). This type of communication is related to the use of social media in disaster emergency and crisis situations. Social media operate as a bridge among first responders, exposed citizens, and citizens who have offered help (Sutton et al. 2008; Tang et al. 2015).

Since two-way communication does not exclude one-way communication, one-way information is still predominant in the cross-national discussion of environmental public risk communication (Jönsson et al. 2016). This form of risk communication is identifiable in wildfire warning systems, lectures, brochures, and news releases that aim to promote public awareness of risk. Although two-way learning is a more inclusive approach to risk policy communication (Pidgeon et al. 2006), it may not be the most suitable form of communication because a more inclusive approach implies multidirectional and interactive learning. The idea of societal learning about wildfire risk involves interactions among the citizens, communities, governments, and other organizations that discuss what each individual can do to create a sustainable approach to wildfire (Olson et al. 2015), which includes evaluation (Fra.Paleo 2015b). Emphasizing learning processes implies the deconstruction of hierarchies among different types of knowledge, capacities, and experiences.

2.2 The Role of the Media in Wildfire Risk Discourse

News reports of wildfires on television and in print media have a substantial impact on the perception and representation of wildfire risk (Carroll and Cohn 2007). However, the approach that is most commonly adopted by mass media in response to disasters has been criticized for its tendency to be sensationalized, inaccurate, overly simplistic, and polarized (Dunwoody 1992). Many journalists have not been trained on how to appropriately cover natural hazard-induced disasters and lack basic scientific knowledge (Lowrey et al. 2007). Too much emphasis may also be placed on the impacts of a disaster, conceivably to increase the appeal of the news to the audience (Quarantelli 2002). However, the media ensure that decision makers, interest groups, and the public are aware of pertinent issues (Barua 2010). Hence, societal values are incorporated or popular topics in the political agenda are highlighted, usually in response to the economic interests of the specific media group.

Although local media provide relevant information in the aftermath of disasters (Rausch 2013; Matthews 2017), their potential role in pre-disaster planning is under-exploited (Ewart and McLean 2018). Disaster planning and preparedness has received limited coverage by local newspapers in the United States (Lowrey et al. 2006) and Turkish (Tekeli-Yesil et al. 2019) contexts, for example. This gap between media coverage of disaster stories and the anticipatory perspective may be explained by the discursive nature of disaster stories.

Generally, figures of speech are used to increase the effectiveness of the discourse (van Dijk 1983), but these figures of speech can either augment or reduce the impact of the information. Metaphors used by the media during disasters may misrepresent reality and strengthen prevailing myths (Tierney et al. 2006; Fu et al. 2012). Because we are interested in investigating the links between risk communication and risk governance, in this article, we address the role played by media discourse in the understanding of risk in two governance systems that have been specifically developed to prevent, anticipate, and cope with wildfires: Rondônia in western Brazil and Galicia in northwestern Spain.

3 Wildfire in Context

In the two study areas (Fig. 1), wildfires are a result of historical processes that have increased the complexity of these social–ecological systems over time due to changes in human–environment interactions, induced by multiple socioeconomic processes and political decisions.

Source: Map based on information from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/)

Location of the two study areas in Brazil and Spain.

Wildfires in Rondônia mainly stem from the rapid and massive transformation of land cover, which places great pressure on the conservation of natural and social–ecological systems. The region evolved rapidly from a system that consisted of a mixture of traditional gathering and extraction systems (for example, indigenous peoples and rubber tapper communities), new technologies (for example, building structures and road networks) and services (for example, education and health), and farming and animal husbandry (combining traditional methods, such as slash-and-burn, with modern practices, such as industrial agriculture and animal husbandry that focus on the global market). Deforestation and wildfires are increasingly connected in the Amazonian environment through clearing fires (Cochrane and Laurance 2002; Adeney et al. 2009; Le Page et al. 2010). Several associated drivers also affect the risk of wildfire in the region, such as the colonization of new land as a result of immigration and population growth, illegal logging, and the advancement of the farming frontline driven by the increased demand for pasture and cash crops to feed industrial husbandry, which is driven by an increasing global demand for beef (Nepstad et al. 2006; Arima et al. 2007; Adeney et al. 2009). Encroachment is the primary driver of tropical forest deforestation and land transitions to farming (De Fries et al. 2010), followed by the construction of infrastructure (Kirby et al. 2006), such as road networks and hydroelectric installations (Lima et al. 2012; Araújo et al. 2017) and all of these practices create a new fire regime.

Wildfires in Galicia are closely associated with a social–ecological system that has rapidly transitioned from a rural subsistence farming economy to an urban society based on a service economy and on certain industrial sectors (wood processing, meat industry, dairy, and seafood processing). Industrialization has been accompanied by intense rural flight and population aging and been tied to the afforestation of farmland and the reforestation of forested areas. Thus, risk can be better understood in the wider socioeconomic and environmental context of southern Europe, including Portugal, France, Italy, and Greece, which have recurrent and frequent large peaks in wildfires (Calviño-Cancela et al. 2016).

The comparative analysis seeks to understand the contribution of local media to wildfire risk perception in two distinct social–ecological systems with diverse geographic scales, history, culture, and intervening forces. The accumulated deforested area in Rondônia from 1988 (when monitoring based on earth observation started) to 2016 amounts to 57,879 km2 (PRODES 2018), an area almost twice the size of the total area of Galicia (29,574 km2), just since 1988. However, wildfire risk in Galicia is socially and environmentally just as relevant. Between 2001 and 2010, wildfires burned 2887 km2 (MAGRAMA 2012), about 9.66% of the region extent. Within the same time frame, wildfires razed 22,184 km2 in Rondônia (PRODES 2018), about 9.34% of the state’s total area (237,576 km2). But, where wildfires in Rondônia are mainly associated with recent colonization and rapid transformation of natural ecosystems, in Galicia they are associated with rapid land-use change in a context of old land occupation. In both cases, however, radical shifts of their social–ecological systems are going on.

4 Methods

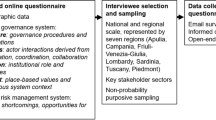

The discourse on wildfire risk in local print media was analyzed, and key informant interviews were used to understand the key features of risk communication and interpret the framing of the discourse. Discourse analysis focuses on language and language use to find evidence of society and social life (Taylor 2013) and entails a systematic interpretation of texts, images, and symbols (Krippendorf 1989). Common approaches include discursive analysis, category analysis, narrative analysis, and framing. The common element shared by these approaches is that they perform a critical analysis of the focus of discourse and the relations between multiple discourses. These approaches also examine the social dimensions such as power relations, ideologies, institutions, and social identities (Fairclough 2013).

According to Lakoff (2010), human beings typically think in terms of unconscious structures called frames. The term frame is the process by which individuals organize and interpret their life experiences and apply interpretive schemas or “primary frameworks” (Goffman 1974). According to Bacchi (2009), Goffman pioneered an intellectual tradition that was followed by van Dijk (1977) and Moscovici (1984), in which frames are considered a form of grouping certain factors to reduce the complexity of the world and make sense of it. Following Kasperson’s (2015) understanding, the experience of risk is the result of communication processes by which groups and individuals interpret risk and acquire risk frames.

Individuals or groups constantly evaluate situations and make decisions related to risk, which is culturally framed and conveyed. When faced with a wildfire crisis, people assess the risk and decide whether to take action (Matlock et al. 2017). The ability of people to reason is also influenced by their knowledge of wildfire risk, emotionally driven inferences about potential loss and damage, and assumptions about wildfire preparedness (Eriksen 2013). The nature of the decision-making process concerning risk depends on intertwined factors, such as the degree of knowledge of the risk, the experience with the risk, and the communication process.

Framing is an issue of problem setting, which is the first step in problem solving. The emphasis on problem solving led people and practitioners to ignore problem setting, which is the process by which we define the decision to be made, the ends to be achieved, and the means that may be chosen (Schon and Rein 1995). Framing wildfire risk in local print media and local actor discourse may elucidate how wildfire risk is interpreted, and this information may also clarify the priorities of these governance systems.

The analysis in the present study involved three phases. First, we identified and interpreted articles that provided information about wildfires in two local print newspapers published in 2015 in Rondônia (Diário da Amazônia) and Galicia (El Progreso). All articles with headlines using the word wildfire were identified. In addition, we included articles related to potential wildfire drivers, such as afforestation, deforestation, animal husbandry, export commodities, grain and timber trade, railroad construction, climate change, and rural flight. How these drivers were portrayed in the two local print newspapers was examined to identify gaps between scientific communication and local risk communication.

Second, the articles were qualitatively classified according to the key topics and coded. A code symbolically conveys a summative, salient, essence-capturing, or evocative attribute for a portion of language-based or visual data (Saldaña 2009). The analytic approach is based on the framework proposed by Ritchie et al. (2003), which follows a sequential process: (1) familiarize with the data, noting initial themes or concepts; (2) generate thematic framework, organizing themes and subthemes; (3) apply thematic framework, label data with number or term; (4) develop descriptive accounts, refining categories; and (5) develop explanatory accounts.

We interviewed key societal actors, using semistructured interviews and open-ended questions within a common standard framework, in both study areas to recognize factors of identified wildfire risk and the key discourse. In total, 65 interviews were conducted in eight municipalities in Rondônia (Fig. 2) from September 2015 to January 2016, and 81 interviews were conducted in 10 municipalities in Galicia (Fig. 3) from June 2014 to August 2015. Three groups of actors were interviewed: farmers (32 in Rondônia and 56 in Galicia), local government representatives (26 in Rondônia and 5 in Galicia), and civil society representatives (7 in Rondônia and 20 in Galicia). The interviews sought to gain knowledge about: (1) the respondents’ perception of changes in the area; (2) disaster risk memory, perception of, attitude towards, and proposed risk mitigation measures, and identified actors involved; (3) the perceived relationship between farming practices and wildfire risk.

Source: Map based on information from IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística/Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics 2016) (https://www.ibge.gov.br/geociencias/cartas-e-mapas/mapas-estaduais.html)

Municipalities in the State of Rondônia, Brazil, where the 65 study interviews were conducted.

Source: Map based on information from IGN (Instituto Geográfico Nacional/National Institute of Geography 2016) (https://www.ign.es/web/ign/portal/cbg-area-cartografia)

Municipalities in the region of Galicia, Spain, where the 81 study interviews were conducted.

5 Results

This section examines the discourse conveyed by local print newspapers in Rondônia and Galicia on wildfires and their role played in risk communication.

5.1 Wildfires in Rondônia: The Role of the Local Media

The articles from Diário da Amazônia dealing with wildfire published throughout a year are listed in chronological order in Table 1. Next, in order to identify the key topics and the relation to a complex reality, they have been grouped into subthematic classes (Table 2).

The increase in the frequency of clearing fires is the most common topic, reflecting an increase in hotspots registered in 2015. However, one op-ed addressing the risk reveals either a perceived low social relevance or a lack of critical perspective in terms of the newspaper.

The increase in clearing fires is followed by the impacts of fire on health, infrastructures, and cities, particularly the threat of fire to airports, houses, phone towers, and cemeteries. This news conveys that the environment is progressively becoming more hazardous to society in general.

Forecast and early warning is a central policy in risk governance, but the focus on this topic is limited, and the topic is treated very differently in articles 1 and 25. Under the influence of Afro-Brazilian religions, psychics as media sources are common on television and in newspapers, especially around New Year’s Eve when future predictions are made. In article 1, a Balorixá (clairvoyant) predicts wildfire disasters for 2015. Article 25 informs about wildfire risk based on meteorological data and warns citizens about high temperatures. Exotericism/ritualism (article 1) and scientific modeling (article 25) are adopted in parallel by the same newspaper in anticipation of disaster. But the newspaper does not provide a sufficient explanation of the nature and accuracy of the information.

The lack of a precautionary approach in governing disaster risk is addressed in op-ed 25, but the dominant reactive approach to fire management is reflected in article 4. This piece describes the first meeting of the Fire Prevention State Committee, which occurred following years of independent work by local and federal departments. The meeting took place in July 2015, during the peak period of both drought and wildfires, and revealed tardy and poorly planned political action. Members of this committee sustained similar criticism. When interviewed and asked about wildfire risk governance, various recurrent arguments arose—for example, a reactive approach adopted by the government that is reduced to only suppression during fire events; an incessant “fight” against successive fires; a dominant military approach to fire suppression that includes concealing information from citizens instead of strengthening risk communication; and a lack of sustained risk communication.

Arsonism is used by the press to support the argument that it is challenging to govern wildfire risk due to the difficulty in identifying arsonists. Because land registration is an ongoing problem in Rondônia, identifying the landowner where a wildfire occurs can be a difficult task. Respondents reported that environmental agencies have no control over environmental crimes on unregistered land, making it difficult to punish offenders. Conflict over land tenure and rights has continued since colonization despite advances in land registration, as regulated by the Forest Code of 2012 (Law 12651 of 25 May 2012).

Ambiguity in the legal provisions regarding arson was identified by respondents as a contributing factor to wildfire risk. Interviewees observed differences between fining small landowners without financial resources and the actions taken against soybean farmers, who are charged for neither wildfires nor improper pesticide use. Differences in the creation of risk by small and large landowners were identified by other interviewees, who argued that the latter do not need frequent fire because they have access to alternative technologies. However, an academic observed that massive land occupation for farming led to careless clearing or burning by landowners with both small and large plots.

The impact of wildfires on flora and fauna in protected areas was addressed in only two articles (11 and 29). Despite an increase in the declaration of protected areas as a result of increasing concern about sustainability, fire is still commonly used in the Amazon to clear forests, burn plant residues, and control weeds in pasture land (Laurance and Williamson 2001; Lima et al. 2012; Araújo et al. 2017). Respondents who worked in protected areas informed the researchers that fire is adopted by commercial animal husbandry operations in Rondônia because it is a less demanding and inexpensive practice to renew pasture.

5.2 Factors Behind Wildfire Risk in Rondônia

Although the articles provided information about wildfire crises and impacts, the causes of wildfire were poorly examined. Logging, animal husbandry, farming—particularly grain production—and highway construction have been identified as wildfire drivers by the academic community (Laurance and Williamson 2001; Cochrane and Laurance 2008). But in Rondônia these same factors are synonymous with economic development in the local media (Tables 3 and 4).

The economic and political relevance of agribusiness is the most recurrent issue. Articles 3, 6, 7, 9, 15, 19, and 22 focus on the meat market, while articles 1, 2, 3, 14, 16, 17, and 19 focus on the production of soybeans. Only article 5 focuses on fish farming as an emerging sector. The essential argument in these articles is that by strengthening these respective sectors, Rondônia may become an economically promising land.

In contrast to what the media suggest, various authors (Cochrane and Laurance 2008; Davidson et al. 2012; Brando et al. 2014) have emphasized that deforestation fires are increasing in Amazonia due to the multiple feedbacks between the rapid expansion of the farming frontier and drought. Nepstad et al. (2006), Arima et al. (2007), and Adeney et al. (2009) stated that the demand for pasture land and cash crops to support industrial animal husbandry, which is driven by the increasing global demand for meat, increased the frequency of deforestation fires in the Brazilian Amazon. The gap between the arguments conveyed by the media and the scientific literature indicates that there is a lack of effective wildfire risk communication between different actors.

Railroad construction is underlined as an improvement that might boost agribusiness, particularly the “soybean railway,” which is the transcontinental line between Brazil and Peru that is examined in articles 12, 13, 14, and 17. The economic interests of China (13), India (16), and the United States (15) in food cropping and livestock in Rondônia are also identified. The progress of the construction of highway BR-319 is reported in article 21. The development of infrastructure has been associated with fires in Rondônia, where the deforestation caused by new settlements is clearly linked to roads (Araújo et al. 2017). Without road access, colonization and deforestation would be limited—more than two-thirds of the deforested areas in the Amazon region are found within 50 km of major paved roads (Kirby et al. 2006). Respondents connect road construction with the advancement of the farming frontier towards the Amazon, which was driven by the development of industrial animal husbandry in the 1980s and by crop farming in the beginning of the 1990s. Despite evidence of the link between road development and deforestation fires, roads are seen as a paradigm of progress by the media and most interviewees.

Although deforestation is very rapid in Rondônia, with rates between 3.858 and 1.243 km2/year from 2004 to 2017 (PRODES 2018), the media interest in this topic is low. The increase in wood production as a result of reforestation with fast-growing species or policies that address deforestation were each reported once in 2015 (articles 4 and 18, respectively). The Brazilian Forest Law prescribes the conservation of legal reserves, as well as the protection of permanent preservation areas. Accordingly, rural private properties in the Amazon must preserve 50% of the property as native forest. In an interview, the State Department for the Environment stated that if a property is not composed of 50% native forest, the owner should either start a reforestation project or buy forestry asset credits from another landowner who has more than 50% native forest on their land.

Two reforestation projects based on native species were identified during the fieldwork in Rondônia: the Ecological Action of Guaporé by the Ecoporé nongovernmental organization (NGO) and the Forest Carbon project developed by the Suruí indigenous people. Simultaneously, reforestation with non-native species started in southern Rondônia over the last decade. Respondents from the forest sector indicated that products such as pine resin are exported to foreign markets, while eucalyptus wood is used as firewood by regional agro-industries and as a resource for rural construction. In 2011, the State Government of Rondônia launched the Planted Forest project to reduce the pressure on native forests, promote economic alternatives to logging, and promote CO2 sequestration, water management, and climate change mitigation. In 2016, this project, which became State Law 85/2016, regulated the conservation of native species and the plantation of pine, eucalyptus, and teak.

When analyzing the discourse of actors from the different governmental bodies that were interviewed, different positions were found. An official from the State Department of the Environment (SEDAM) argued that wildfire risk is not created because the Planted Forest project is being implemented in regions that are not suitable for farming, and the program reduces the pressure on native forests. But an official from the Department for Protected Areas (ICMBio—Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation) warned that the program was promoting the replacement of native species with fire-tolerant species. These diverging viewpoints concerning reforestation illustrate the contrasting discourse and understanding of potential wildfire risks.

5.3 Wildfires in Galicia: The Role of the Local Media

In 2015, the local newspaper El Progreso published 69 articles that included information about wildfires in Galicia (Tables 5 and 6).

Arsonism is the most common topic in the news throughout the year. News articles 26, 28, 32, 35, 38, 40, and 44 argue that fires usually occur when fire suppression teams are off-duty. The discourse on the criminal nature of wildfires is reinforced by paid advertisements by the regional government, which convey a message of zero tolerance and indictment against arsonists. The communication strategy of the regional government—to blame arsonists to divert accusations of political negligence—is criticized in articles 28, 44, and 61. The term pyromania, a disorder defined in psychology as “categorized by an impulse to deliberately start fires as a way of relieving tension and typically includes gratification or relief afterward” (Soeiro and Guerra 2015) is used (1) to support the idea of the unpredictability of outbreaks, as well as the uncertainty associated with early warning and the complexity of response.

Numerous articles focus on how fires threaten homes and displace residents. Considering the dispersed population pattern in Galicia, respondents argued that the wildland-urban interface (WUI) was an extremely important risk factor. In WUI areas, residential land use is mixed with forestland (Radeloff et al. 2005). Wildland–urban interface areas in Galicia cover 8.3% of the region, particularly along the Atlantic coast and in the southwest due to the higher urban density (Chas-Amil et al. 2013), where fire ignition events were approximately twice as frequent as in non-WUI areas. The highest rate of ignition events in WUI areas mainly occurred next to forest plantations, and less in native forest and farmland interfaces (Calviño-Cancela et al. 2016).

The articles that provide information about the environmental impacts of fires describe fire in protected areas in terms of devastation. “Protected area” is a term used with a markedly positive connotation of a valuable treasure, implying priceless loss if damaged. This framing refers to the moral imperative to preserve natural resources. It is not unusual for this kind of frame to be used by environmentalists (article 2). Coherent framing of issues relating to the natural world is a commitment to environmental and social movements (Lakoff 2010).

The significant number of news pieces highlighting the use of airplanes, helicopters, and personnel in fire suppression reinforce the idea that the government’s efforts to deal with wildfires are limited to the use of technological and human resources and typically include a reactive approach. Usually, temporary mitigation teams cooperate with government officials through public–private partnerships. Op-ed 62 criticizes the dependence on the private sector, suggesting that if fire suppression is more lucrative than prevention, wildfires may continue.

The prevention procedures described in articles 47, 48, and 49 focus on other measures that have been adopted by the regional administration to regulate land use, hire human resources, and prohibit stubble and residue burning during the high-risk period.

Most respondents believe that the forest policy of the regional government prioritizes fire suppression and, therefore, fewer resources are allocated to prevention. This approach, mostly based on clearing vegetation in hazardous areas, was criticized by most respondents due to its high costs.

When referring to fires, various terms—such as plague, chronic disease, local apocalypse, ecological terrorism, or hell—are used as metaphors. According to Matlock et al. (2017), the metaphor of fire as a monster is frequently used to refer to events that are out of control. In our opinion, the use of the metaphor serves to turn disaster into a spectacle. Such metaphors seek to enhance the effectiveness of the discourse. However, by emphasizing the devastating impact of wildfires, the other factors behind the construction of risk are forgotten.

Among the articles that addressed wildfires, 72.5% were published between July and August, that is, the wildfire peak period, which underpins the reactive nature of risk communication. Nevertheless, in 2015, wildfires also occurred in winter (December), as described in articles 66, 67, 68, and 69. Growing uncertainties concerning the changing environmental conditions emphasize the need for continuous and preventive fire management.

5.4 Intervening Factors in Wildfires in Galicia

Similar to how agribusiness is presented as a symbol of progress in Rondônia, the economic strength of the forestry sector is highlighted in the local news in Galicia (Tables 7 and 8), while the persistent crisis of the rural economy and the social and environmental problems are poorly addressed.

Various articles convey the idea of forestry as a dynamic economic sector that creates jobs. However, the adverse impacts of forestry are rarely addressed. Conflicts are cited only in article 1, which describes the withdrawal of the representative from the industry of wood derivatives in the consortium promoted by the regional government. The members of the consortium are representatives from different organizations who gather to approve prevention and defensive plans against forest fires. The crisis of the rural economy is only indirectly approached in articles that provide information about the performance of dairy farming. Galician society has followed a process of urbanization since the 1960s and has shifted to a service-based economy. After accessing the European Community (EC) in 1986, the specialization in dairy farming was followed by a technological change that ultimately led to the collapse of the traditional farming model, resulting in the decline of a large number of small farms and the afforestation of arable land (Guimarey and Corbelle 2012). This change was noted by a villager, who stated that in the past, each farm had at least two or three dairy cows, while currently, the few remaining farms have approximately 200 cows. The interviewee underlined that this specialization was driven by the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). This policy was initially based on price support, but from the mid-1980s, it progressively transformed to be based on income support due to budget pressure on reducing agricultural surpluses (López 2000). Although rural abandonment was the common argument of the villagers who were interviewed, the topic was rarely reported in the newspaper (except for article 18). Similarly, the new land regulation and its foreseeable impacts are addressed only in article 13. Thus, we found that both academics and local residents frame wildfires differently than the local newspaper.

6 Conclusion

This research examined how the local print media in the two study areas framed wildfire risk and compared this type of framing to that by local people and experts. The main conclusion is that wildfire disasters are presented as mere spectacles during the peak season because, while losses and damage are emphasized in the media to capture interest, the ultimate drivers of risk are not appraised to support a consensus and create a convergence of effective approaches (Fra.Paleo 2013). The adopted approach does not promote social learning about risk, which involves recognizing wildfire risk as a social, political, economic, and environmental problem, to promote the development of coherent risk governance.

Research has shed some more light on the disparity between the topics highlighted by the local print media and academic studies, points to a conflict in the understanding of wildfire risk, and is evidence of a lack of a social dialogue used to address the complexity of wildfire risk. The governance systems lack appropriate strategies to coordinate and channel information from government sources and local mass media to citizens. Instead of tackling the complexity of the problem, the dominant discourse is reductionist when it emphasizes the criminal dimension and conveys wildfire as an unmanageable process. The appeal for punishment points to the government’s failure to act proactively and is an obstacle to communicating the multifaceted nature of the risk. The reactive approach adopted by the government strengthens the suppression component and promotes new specializations, ministerial services, and bureaucracy. According to Debord (2006), this specialization will be measured by its own efficacy. In contrast, proactive risk governance stimulates dialogue and negotiation among all actors to build consensus (Fra.Paleo 2015b) regarding land use and the creation of risk.

Discourse analysis of disaster news stories requires a great effort of data collection, and identification and categorization of key themes is influenced by a high level of subjectivity. Accordingly, the use of this method in other geographical areas for the purpose of comparison is limited, as well as the longitudinal analysis of the role of the local media. Thus, the adoption of quantitative techniques to study in parallel the content of disaster risk messages communicated in local media may moderate this limitation.

References

Adeney, J.M., N.L. Christensen Jr, and S.L. Pimm. 2009. Reserves protect against deforestation fires in the Amazon. PLos One 4(4): Article e5014.

Araújo, E., P. Barreto, S. Baima, and M. Gomes. 2017. The most deforested protected areas in the Legal Amazon between 2012 and 2015 (Unidades de conservação mais desmatadas da Amazônia Legal (2012–2015)). Belém: Instituto do Homem e Meio Ambiente da Amazônia. http://imazon.org.br/PDFimazon/Portugues/livros/UCSmaisdesmatadasAmazonia_2012-2015.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb 2018.

Arima, E.Y., C.S. Simmons, R.T. Walker, and M.A. Cochrane. 2007. Fire in the Brazilian Amazon: A spatially explicit model for policy impact analysis. Journal of Regional Science 47(3): 541–567.

Bacchi, C. 2009. The issue of intentionality in frame theory: The need for reflexive framing. In The discursive politics of gender equality, ed. E. Lombardo, P. Meier, and M. Verloo, 39–55. London: Routledge.

Barua, M. 2010. Whose issue? Representations of human–elephant conflict in Indian and international media. Science Communication 32(1): 55–75.

Brando, P.M., J.K. Balch, D.C. Nepstad, D.C. Morton, F.E. Putz, M.T. Coe, D. Silvério, M.N. Macedo, et al. 2014. Abrupt increases in Amazonian tree mortality due to drought–fire interactions. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(17): 6347–6352.

Calviño-Cancela, M., M.L. Chas-Amil, E.D. García-Martínez, and J. Touza. 2016. Wildfire risk associated with different vegetation types within and outside wildland-urban interfaces. Forest Ecology and Management 372: 1–9.

Carroll, M.S., and P. Cohn. 2007. Community impacts of large wildland fire events: Consequences of actions during the fire. In People, fire and forests: A synthesis of wildfire social science, ed. T.C. Daniel, M.S. Carroll, C. Moseley, and C. Raish, 104–123. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press.

Chas-Amil, M.L., J. Touza, and E. García-Martínez. 2013. Forest fires in the wildland–urban interface: A spatial analysis of forest fragmentation and human impacts. Applied Geography 43: 127–137.

Cochrane, M.A., and W.F. Laurance. 2002. Fire as a large-scale edge effect in Amazonian Forests. Journal of Tropical Ecology 18(3): 311–325.

Cochrane, M.A., and W.F. Laurance. 2008. Synergisms among fire, land use, and climate change in the Amazon. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 37(7): 522–527.

Davidson, E.A., A.C. de Araújo, P. Artaxo, J.K. Balch, I.F. Brown, M.M.C. Bustamante, M.T. Coe, R.S. DeFries, et al. 2012. The Amazon basin in transition. Nature 481: 321–328.

Debord, G. 2006. A sick planet (El planeta enfermo). Barcelona: Anagrama (in Spanish).

De Fries, R.S., T. Rudel, M. Uriarte, and M. Hansen. 2010. Deforestation driven by urban population growth and agricultural trade in the twenty-first century. Nature Geoscience 3(3): 178–181.

De Marchi, B. 2015. Risk governance and the integration of different types of knowledge. In Risk governance: The articulation of hazard, politics and ecology, ed. U. Fra.Paleo, 149–165. New York and London: Springer.

Dunwoody, S. 1992. The media and public perceptions of risk: How journalists frame risk stories. In The social response to environmental risk, ed. D.W. Bromley, and K. Segerson, 75–100. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Netherlands.

Eriksen, C. 2013. Gender and wildfire: Landscapes of uncertainty. London: Routledge.

Ewart, J., and H. McLean. 2018. Best practice approaches for reporting disasters. Journalism. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918757130.

Fairclough, N. 2013. Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. London: Routledge.

Fra.Paleo, U. 2013. A functional risk society? Progressing from management to governance while learning from disasters. In World Social Science Report 2013: Changing Global Environments, ed. U. Fra.Paleo, 434–438. Paris: UNESCO.

Fra.Paleo, U. 2015a. Introduction. In Risk governance: The articulation of hazard, politics and ecology, ed. U. Fra.Paleo, 1–16. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Netherlands.

Fra.Paleo, U. 2015b. Structure, process, and agency in the evaluation of risk governance. In Risk governance: The articulation of hazard, politics and ecology, ed. U. Fra.Paleo, 237–273. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Netherlands.

Fu, K.W., L. Zhou, Q. Zhang, Y.Y. Chan, and F. Burkhart. 2012. Newspaper coverage of emergency response and government responsibility in domestic natural disasters: China-US and within-China comparisons. Health, Risk & Society 14(1): 71–85.

Goffman, E. 1974. Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Guimarey, B., and E. Corbelle. 2012. Characterization of two forest repopulation processes subsequent to the entry of Galicia into the European Union (Caracterización dos procesos de repoboación forestal posteriores á entrada de Galicia na Unión Europea). In Surveying territories: Papers on land use planning (Territorios a examen: Trabajos de ordenación territorial), ed. R. Crecente Maseda, U. Fra.Paleo, 41–56. Lugo, Spain: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela (in Spanish).

Jönsson, A.M., M. Boström, M. Dreyer, and S. Söderström. 2016. Risk communication and the role of the public: Towards inclusive environmental governance of the Baltic Sea? In Environmental governance of the Baltic Sea, ed. M. Gilek, M. Karlsson, S. Linke, and K. Smolarz, 205–227. Basel, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, Springer Nature Switzerland.

Kasperson, R.E. 2015. Risk governance and the social amplification of risk: A commentary. In Risk governance: The articulation of hazard, politics and ecology, ed. U. Fra.Paleo, 485–488. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Netherlands.

Kirby, K.R., W.F. Laurance, A.K. Albernaz, G. Schroth, P.M. Fearnside, S. Bergen, E.M. Venticinque, C. Da Costa. 2006. The future of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Futures 38(4): 432–453.

Krippendorf, K. 1989. Content analysis. In International encyclopedia of communication, ed. E. Barnouw, G. Gerbner, W. Schramm, T.L. Worth, and L. Gross, 403–407. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lakoff, G. 2010. Why it matters how we frame the environment. Environmental Communication 4(1): 70–81.

Laurance, W.F., and G.B. Williamson. 2001. Positive feedbacks among forest fragmentation, drought, and climate change in the Amazon. Conservation Biology 15(6): 1529–1535.

Le Page, Y., G.R. van der Werf, D.C. Morton, and J.M.C. Pereira. 2010. Modeling fire-driven deforestation potential in Amazonia under current and projected climate conditions. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JG001190.

Lima, A., T.S.F. Silva, R.M. de Feitas, M. Adami, A.R. Formaggio, and Y.E. Shimabukuro. 2012. Land use and land cover changes determine the spatial relationship between fire and deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Applied Geography 34: 239–246.

López Iglesias, E. 2000. The Galician agricultural sector at the door of the 21st century (O sector agrario galego ás portas do século XXI: balance das súas transformacións recentes). Revista Galega de Economía 9(1): 167–196 (in Spanish).

Lowrey, W., W. Evans, K.K. Gower, J.A. Robinson, P.M. Ginter, L.C. McCormick, and M. Abdolrasulnia. 2007. Effective media communication of disasters: Pressing problems and recommendations. BMC Public Health 7(1): Article 97.

Lowrey, W., K. Gower, W. Evans, and J. Mackay. 2006. Assessing newspaper preparedness for public health emergencies. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 83(2): 362–380.

Matlock, T., C. Coe, and A.L. Westerling. 2017. Monster wildfires and metaphor in risk communication. Metaphor and Symbol 32(4): 250–261.

MAGRAMA (Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente/Ministry of Agriculture, Nutrition and Environment). 2012. Wildfires in Spain, 2001–2010 (Los Incendios Forestales en España. Decenio 2001–2010). Madrid: Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente (in Spanish).

Matthews, J. 2017. The role of a local newspaper after disaster: An intrinsic case study of Ishinomaki, Japan. Asian Journal of Communication 27(5): 464–479.

Morss, R.E., J.L. Demuth, H. Lazrus. 2017. Hazardous weather prediction and communication in the modern information environment. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 98(12): 2653–2674.

Moscovici, S. 1984. The phenomenon of social representations. In Social representations, ed. R. Farr, and S. Moscovici, 3–70. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nepstad, D., S. Schwartzman, B. Bamberger, M. Santilli, D. Ray, P. Schlesinger, and A. Rolla. 2006. Inhibition of Amazon deforestation and fire by parks and indigenous lands. Conservation Biology 20(1): 65–73.

Olson, R.L., D.N. Bengston, L.A. DeVaney, T.A.C. Thompson. 2015. Wildland fire management futures: Insights from a foresight panel. Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service.

Pidgeon, N., P. Simmons, and K. Henwood. 2006. Risk, environment and technology. In Risk in social science, ed. P. Taylor-Gooby, and J. Zinns, 94–116. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

PRODES (Projeto de Monitoramento do Desmatamento na Amazônia Legal por Satélite/Amazon Deforestation Monitoring Project). 2018. Monitoring the Brazilian Amazon forest by satellite (Monitoramento da Floresta Amazônica Brasileira por Satélite). http://www.obt.inpe.br/OBT/assuntos/programas/amazonia/prodes. Accessed 10 Feb 2018 (in Portuguese).

Quarantelli, E.L. 2002. The role of the mass communication system in natural and technological disasters and possible extrapolation to terrorism situations. Risk Management 4(4): 7–21.

Radeloff, V.C., R.B. Hammer, S.I. Stewart, J.S. Fried, S.S. Holcomb, and J.F. McKeefry. 2005. The wildland–urban interface in the United States. Ecological Applications 15(3): 799–805.

Rausch, A.S. 2013. The regional newspaper in post-disaster coverage: Trends and frames of the Great East Japan Disaster, 2011. Keio Communication Review 35: 35–50.

Renn, O. 2014. Four questions for risk communication: A response to Roger Kasperson. Journal of Risk Research 17(10): 1277–1281.

Ritchie, J., L. Spencer, and W. O’Connor. 2003. Carrying out qualitative analysis. In Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers, ed. J. Ritchie, L. Spencer, W. O’ Connor, 219–262. London: SAGE Publications.

Saldaña, J. 2009. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. London: SAGE Publications.

Schon, D.A., and M. Rein. 1995. Frame reflection: Toward the resolution of intractable policy controversies. New York: Basic Books.

Soeiro, C., and R. Guerra. 2015. Forest arsonists: Criminal profiling and its implications for intervention and prevention. European Police Science and Research Bulletin 11: 34–40.

Sood, R., G. Stockdale, and E. Rogers. 1987. How the news media operate in natural disasters. Journal of Communication 37(3): 27–41.

Sutton, J., L. Palen, and I. Shklovski. 2008. Backchannels on the front lines: Emergent uses of social media in the 2007 southern California wildfires. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, 4–7 May 2008, Washington, DC, USA, 1–9.

Tang, Z., L. Zhang, F. Xu, and H. Vo. 2015. Examining the role of social media in California’s drought risk management in 2014. Natural Hazards 79(1): 171–193.

Tekeli-Yesil, S., M. Kaya, and M. Tanner. 2019. The role of the print media in earthquake risk communication: Information available between 1996 and 2014 in Turkish newspapers. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 33: 284–289.

Taylor, S. 2013. What is discourse analysis? London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Tierney, K., C. Bevc, and E. Kuligowski. 2006. Metaphors matter: Disaster myths, media frames, and their consequences in Hurricane Katrina. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 604(1): 57–81.

Van Dijk, T.A. 1977. Semantic macro-structures and knowledge frames in discourse comprehension. In Cognitive processes in comprehension, ed. M.A. Just, and P.A. Carpenter, 332. Brandon, VT: Psychology Press.

Van Dijk, T.A. 1983. Discourse analysis: Its development and application to the structure of news. Journal of Communication 33(2): 20–43.

Acknowledgements

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES, Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel)—Finance Code 001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Silva, N.T.C., Fra.Paleo, U. & Ferreira Neto, J.A. Conflicting Discourses on Wildfire Risk and the Role of Local Media in the Amazonian and Temperate Forests. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 10, 529–543 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-019-00243-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-019-00243-z