Abstract

In urban environments characterized by rich diversity across language, migration status, demographic profiles, and usage of different forms of media, there can be significant challenges to ensuring that particular disaster risk reduction (DRR) communications reach those potentially affected. This article presents a study with 20 Pacific Island community leaders and connectors about their communities’ perspectives and anticipated responses to natural hazards in Auckland, New Zealand. Home to the largest population of Pacific people in the world, Auckland provides the basis for understanding the complexities of delivering disaster information across numerous community groups. The rich cultural and linguistic backgrounds of multiple Pacific communities living in this city highlight the need to consider the complexities of disaster messaging related to natural hazards. In particular, the article forwards the importance of incorporating the guiding concepts of reach, relevance, receptiveness, and relationships into a DRR approach with culturally and linguistically diverse groups. These concepts are presented as an embedded guiding framework that can helpfully inform disaster communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Disaster messaging is only effective if the population it is intended for embraces it. In societies characterized by rich cultural and linguistic diversity, there can be numerous challenges to ensuring that particular disaster risk reduction (DRR) initiatives reach those who are potentially affected. For minority communities, several factors can affect people’s resilience to hazards. These considerations can relate to language and cultural barriers, lack of local knowledge (including hazard awareness), limited social networks, access to fewer resources, marginalization, and inadequate familiarity with local organizational structures that provide disaster support (Guadagno 2016). Yet, these communities can also exhibit particular capabilities in dealing with hazards and disasters, for example through prior experience in their countries of origin. Alongside building upon the strengths that exist within communities, ensuring access to appropriate, accurate, and timely risk information prior to a disaster can significantly reduce disaster vulnerabilities (Shepherd and van Vuuren 2014).

As a country located within the Ring of Fire, New Zealand is exposed to a number of natural hazards that include earthquakes, volcanoes, storms, tsunamis, and flooding. The country’s largest city, Auckland, is one of the most ethnically diverse urban environments in the world with more than 200 spoken languages. The city has also been dubbed the Polynesian capital of the world (Dunsford et al. 2011), as it harbors the largest population of Pacific Island origin globally. The South Pacific constitutes one of the richest linguistic regions globally. These contexts present additional complexities for engaging with culturally and linguistically diverse groups about disaster risk reduction.

As there is evidence of increased frequency and impact of natural hazards (see NOAA 2018), there is a need to consider how such events affect localities characterized by diversity. This is particularly the case for urban environments that have been heavily influenced by current and historical migration processes. As different groups relocate, they bring rich human, linguistic, cultural, and social capital that influences how they might perceive and respond to a disaster.

Presenting a study with 20 current and emerging Pacific Island leaders about their perspectives on natural hazards and possible responses, this article examines the complexities of engaging with groups characterized by unique demographic traits and contexts. Through using the theoretical lenses of superdiversity and social capital, we show how the concepts of reach, relevance, receptiveness, and relationships provide some guiding principles to engage with Pacific Island groups.

2 Superdiversity and the Construction of “Community”

Communicating natural hazard risks needs to strike a balance between providing accurate information and delivering this in a way that does not cause undue panic or anxiety. Discussing disasters (and the associated uncertainty of any given event) openly and transparently builds and maintains trust (Barclay et al. 2008). Trust determines the credibility of the message and source and affects the willingness of people to engage, leading to self-responsibility and empowerment (Kuhlicke and Steinführer 2012). Such knowledge also engenders confidence and vigilance among the public since a community that is aware of its vulnerability to disasters is more likely to take action (Gonzalez-Muzzio and Sandoval Henriquez 2015). Minority groups’ awareness of local hazards and risk management structures and procedures, and their access to information and warnings can be fostered by developing translated, understandable, and culturally appropriate communications and focusing outreach on nontraditional channels such as minority media, targeted workshops, and door-to-door communication (Guadagno 2016).

People are more likely to respond effectively to hazards when they are cognizant of the risk level, if they perceive the direct risk to themselves or their families, and when they have previous disaster experience (Eisenman et al. 2007). During Hurricane Katrina in August 2005, minority groups in New Orleans, Louisiana, and elsewhere along the Gulf of Mexico coast were disproportionately affected by the disaster, and were less likely to evacuate. The reasons for this are complex, but were largely assigned to lower levels of preparedness, fewer evacuation resources, and less access to relief and recovery services (Tierney 2014). This could be due to not understanding or misjudging the levels of risk, the influence of others that can help or hinder people’s response, the fear of losing livelihoods, or the urge to protect assets.

The Canterbury Earthquakes that devastated the city of Christchurch on the South Island of New Zealand between 2010 and 2011 also had adverse impacts on migrant communities because there were issues of providing understandable and appropriate information to groups characterized by cultural and linguistic diversity. To mitigate the negative impacts, various agencies worked together to create sites where community leaders could access information that could be disseminated through various channels in their communities and radio messaging was delivered in multiple languages (Wylie 2012). This work highlighted the necessity and complexity of providing information to multiple groups in a postdisaster setting with ongoing aftershocks.

There is a growing recognition of the complexities of communities and the importance of understanding these contexts in order to engage and target risk strategies. Community membership is fluid, and identity markers intersect across gender, age, linguistics, culture, community size, and length of settlement. Therefore, a singular approach to communication and engagement does not work for all. For example, older people are less likely to learn a new language, younger generations may more readily embrace technologies, and numerous studies clearly show that how disasters play out can be heavily influenced by gender (Tierney 2014).

The ways in which superdiversity (Vertovec 2007) has become prevalent in many urban societies highlights how mobility and demographic variability influence the nature of people’s relationships and power relations. Vertovec (2007) refers to this trend in many urban centers as the “diversification of diversity”, where it is now necessary to go beyond traditional markers of diversity (for example gender, age, ethnicity, and religion) to consider how labor market opportunities, various visa regimes, new mobilities, and civil society attachments sit alongside one another to create new and dynamic social groupings. This awareness is also necessary for disaster messaging in cities such as New Zealand’s most populous city.

Auckland is a city of 1.6 million people and more than 200,000 identify as being from a Pacific Island heritage. Migration of Pacific people to New Zealand has a long history, mostly reflecting former colonial ties (Lee 2009). There are numerous Pacific people groups in Auckland, with the largest of these identifying as Polynesian, namely: Samoan (95,916), Tongan (46,971), and Cook Islanders (36,549) (Auckland Council 2015). Auckland is home to about two-thirds of New Zealand’s Pacific people population, the majority of whom are now born in New Zealand (Dunsford et al. 2011). There are also significant numbers of new Pacific migrants, arriving under family reunification categories and quota systems, as well as from Pacific island nations that are in free association with New Zealand (Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau) whose inhabitants hold New Zealand citizenship (Lee 2009; Dunsford et al. 2011).

Auckland Council (2015) acknowledges that over 33% of Pacific people are under the age of 15 (compared to 20.9% of the general population) and that Pacific workers are overrepresented in lower-skilled and lower-paid occupations. Two-thirds of Pacific people are more likely to rent rather than live in their own home (compared to 30% of the majority European—Pākehā—ethnic group). There is also a relatively high number of Pacific people in Auckland with little or no English language skills. Out of a total of close to 50,000 Aucklanders who cannot speak English, about 7000 are Samoans and 3000 are Tongans (Auckland Council 2017). As members of transnational communities, Pacific peoples identify strongly with their island nation and even a particular island or village of origin (Lilomaiava-Doktor 2009; Macpherson and Macpherson 2009). Other major identifiers for Pacific peoples in Auckland are church membership and suburb within the city, intersecting with a range of other factors, including gender, generation, and age (Dunsford et al. 2011).

3 Mapping the Disaster 4Rs and Social Capital

Within New Zealand and other countries, agencies tasked with mitigating the risks associated with disasters often focus on the 4Rs: Readiness, Reduction, Response, and Recovery. New Zealand’s Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management (2018) defines these terms as follows:

-

Readiness Developing operational systems and capabilities before a civil defense emergency happens; including self-help and response programs for the general public, and specific programs for emergency services, lifeline utilities, and other agencies.

-

Reduction Identifying and analyzing long-term risks to human life and property from hazards; taking steps to eliminate these risks if practicable, and, if not, reducing the magnitude of their impact and the likelihood of their occurring.

-

Response Actions taken immediately before, during, or directly after a civil defense emergency to save lives and protect property, and to help communities recover.

-

Recovery The coordinated efforts and processes to bring about the immediate, medium-term, and long-term holistic regeneration of a community following a civil defense emergency.

In relation to these, disaster researchers are increasingly looking to social capital as a way to theorize how people and communities are able to mobilize resources, access information, and respond/recover to disaster events (Eisenman et al. 2007; Mathbor 2007). Some even argue that social capital is a primary if not “the” principal resource for disaster preparedness and response (Aldrich 2012; Tierney 2014). While there are several different social capital theories, much of this disaster literature draws on Putnam’s (2000) three typologies: bonding, bridging, and linking. Bonding and bridging capital represent horizontal relationships within and across communities whereas linking capital is typified as vertical connections between people and structures. Generally, bonding capital facilitates strong and supportive community relationships characterized by people sharing strong commonalities (ethnicity, religion, geographic location). Bridging capital, on the other hand, facilitates access to new resources and opportunities (employment, education, social networking, and information) through the power of weak ties and broadens one’s social network. Linking capital can provide people access to information and resources. However, marginalized communities often have limited access to linking capital and may not trust the institutions and structures that are purported to support them. Although several writers caution about the dangers of social capital, particularly in instances where there is only the presence of one type, social capital is seen as a critical element for disaster risk reduction (Aldrich 2012; Tierney 2014).

These various forms of capital strongly relate to disaster communications. Effective and responsible risk communication is considered to occur when working relationships are established amongst all interested parties (Infanti et al. 2013). This is a two-way interactive process that recognizes different values and treats the public as a full partner, requiring knowledge, planning, preparation, skill, and practice (Covello et al. 2001). Bonding capital helps to ensure that disaster messaging can reach numerous parts of a given community. Community social capital reduces community distress, and community distress suppresses social capital (Mathbor 2007). A sense of belonging and an involvement in the participatory process is a result of agency and generates knowledge, self-confidence in one’s abilities, and development of ownership and capabilities (Marlowe 2015). Bridging capital can assist with connecting community leaders and organizers with important information to which a given community may not have access, while linking capital provides the basis for an environment of trust to exist between institutions and communities.

Without these forms of capital, a risk communication response can be inefficient and can do more harm than good in instances where personnel lack knowledge of diverse communities and provide minimal consultation (Covello et al. 2001). Thus, social capital is a key determinant for disaster risk reduction and builds an effective component of a disaster communication strategy, particularly in sites characterized by superdiversity.

4 Study Design

This study used a qualitative case study approach with the aim of generating in-depth understandings about Pacific Island leaders’ perspectives on natural hazards through establishing a relationship of trust between researchers and research participants. We conducted semistructured interviews with 20 Pacific Island leaders or connectors about the perceived risks and possible responses to natural hazards in the Auckland region. These participants were from the following nationalities with 12 males and 8 females. About half of the participants were under the age of 35. Ten respondents were selected from the Samoan community and four from the Tongan community, which roughly reflects the representation of these two largest Pacific communities in Auckland. The other six respondents were of Cook Islands, Tokelau, and Kiribati origin or had a mixed Pacific nationality background. Twelve participants were male and eight were female.

Two Samoan research assistants (coauthors of this article) recruited the participants by email as people who were identified as currently having leadership positions or having aspirations to become future leaders, such as members of the Auckland student population. To ensure that this research project was responsive to research ethics in practice, the research assistants were trained about negotiating multiple roles in the community if they were already known to some leaders and how to keep the research project separate from other commitments. In particular, we focused on how they should negotiate these roles as an “insider” and “outsider” whose status shifted along a continuum depending on which person they were engaging to address concerns about conflict of interest and possible coercion (see Court and Abbas 2013). The semistructured interviews focused on four thematic areas:

-

Understanding of disasters—How do Pacific people in key leadership positions of their respective communities perceive the risk of natural hazard-induced disasters in Auckland?

-

Use of Information and Communications Technology (ICT)—Where do Pacific community leaders in Auckland get information on disaster risk and preparedness? Channels, barriers? What role does ICT play in Pacific communities and how can it be harnessed for improving awareness and preparedness?

-

Relationship with the wider society and disaster response—Role of disaster experience, social networks, sense of belonging that informs possible disaster responses.

-

Capacities and potential vulnerabilities—What are the particular capacities and potential vulnerabilities of Pacific communities as seen by their leaders?

Interviews ranged in duration from 30 min to 1 h and were conducted in a quiet place of the participant’s choosing—most often in someone’s home. All interviews were conducted in English.

The analysis followed a process of establishing initial and focused codes as outlined by Saldaña (2009). We developed initial codes by first doing line by line coding to then develop groupings of descriptive codes that related to the participants comments that related to perspectives on disasters, possible responses to natural hazards, community demographics, Pacific Island history, and various forms of communication. From this, memos were written about each participant and the associated emergent codes. We then developed focused codes that had greater analytic power that allowed us to examine how the role of trust, the politics of leadership, transnational networks, perceived/actual hazard risk, and a sense of belonging informed the four thematic areas noted above. From this process we established a focus on the four Rs of “reach,” “relevance,” “receptiveness,” and “relationships” as outlined in the findings below. Throughout this analytic process, we checked back with the Samoan researchers on the team to confirm its accuracy. The project received ethics approval from the associated university institution.

5 Findings

The participants’ comments illustrated a deep understanding of their communities and provided invaluable insight as to how best engage these communities and what issues were pertinent to them. In particular, they emphasized the capacities and strengths that they have as a community and the potential vulnerabilities that could expose them to greater risk in the event of a disaster. Within this awareness, it is essential to recognize how everyday vulnerabilities (poverty, insecure housing, unemployment, discrimination) can be magnified in a disaster context.

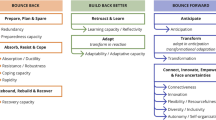

From these discussions, we developed the four main categories that emerged from the data, namely reach, relevance,Footnote 1 receptiveness, and relationships—effectively another 4Rs that map across the 4Rs of disasters (readiness, reduction, response, and recovery). We define the terms below and then outline the specifics of each separately.

-

Reach—the degree to which any communication strategy will get to the person/group of interest;

-

Relevance—the degree to which any communication is seen as being relevant to the target audience;

-

Receptiveness—the degree to which engagement is done in ways that are seen as culturally resonant;

-

Relationships—the way in which two or more people or things are connected, or the state of being connected.

These Rs are relatable to another but are not subsumable. After presenting each of these Rs, we will then bring these together to outline how these concepts can help guide disaster policy and engagement with culturally and linguistically diverse populations such as those identifying as being from the Pacific Islands.

5.1 Reach: Establishing Communication Strategy Success

Ensuring that any given communication strategy reaches a target audience is key to its success. Across the various Pacific Island leaders, we found several important considerations that influence reach. A significant part of this was establishing trust—from what sources or from whom would you trust any sort of messaging.

The majority of participants in this study acknowledged a radio station known as Radio 531pi (Pacific Islands). It has a morning and afternoon show that is primarily directed at first- and second-generation Pacific migrants to Auckland and then hosts an evening program that runs from 6 p.m. into the night that caters to nine different Pacific Island populations. The older and more established community leaders emphasized that it was something that would be central to communicating disaster risk and response.

For the elders, the radio station is the best way [to communicate hazard-related information] and it has to be the Samoan language. (Samoan, female)

I think almost [the] majority of our people they listen to the radio because that’s the only method where they can advertise their different community’s functions. (Kiribatian, male)

However, while most participants acknowledged it, not all would rely on it. Many younger respondents mentioned social media, particularly Facebook, as an emerging channel of everyday communication.

I think digital technology will help immensely with our young Pasifika—a lot of them are computer-literate now. And over 60% of them are New Zealand born. I think being able to leverage and use technology especially in spreading the awareness—the reach is a lot faster and quicker. (Samoan, male)

I think social media has impacted positively especially with our older population even if they don’t know how to use social media. There is always a young one around—the kids or the grandkids, to work it and pass the information through. (Cook Islander, male)

Again, the older community members were more cautious about the reach of Facebook as not all community members used it. There are also many others who do not have smart phones or even an Internet connection. While some participants related this to generational issues or gender differences, others linked it to socioeconomic differentiation. For these groups, a social media approach would be entirely ineffective:

I don’t think for the elders especially, they don’t have the knowledge yet to do these Facebook or emails […] they cannot access this Facebook, you know, so we come back to square one of phone calling and text messages. (Samoan, female)

I’m not sure about the poorer communities, if they can afford cell phones or smart phones that have new updates and that. (Samoan, male)

All participants noted the importance of working with churches to spread disaster messaging and the need to get buy-in from the associated ministers. For Pacific people, “churches have been a major rallying point for community life” (Dunsford et al. 2011, p. 5). In the 2013 census, 73% of New Zealand’s Pacific population reported themselves to be Christian and only 17.5% of Pacific peoples stated that they do not belong to a religion, as compared to 46.9% of European New Zealanders, 46.3% of Māori, and 30.3% of the Asian Population (Stats NZ 2018).

Several interviews revealed particular groups that are at risk of not being in reach of disaster-related information both before and during a disaster event. One group includes those who came to New Zealand on a temporary work permit or visitor visa but stayed beyond their legal permits. This group is likely to remain under the radar of government agencies tasked with providing disaster risk information and relief services.

We’ve got a large group of overstayers here, so it would be harder for them to connect. (Tuvaluan/Kiribatian, female)

Other groups at risk that were mentioned by participants were the elderly with no leadership roles, as well as the less educated and less technology-savvy Pacific people. There is also a relatively high number of Pacific people who do not speak English. Collaborating with Radio 531pi and working through trusted leaders could be an important strategy to overcome language barriers. What becomes clear is that reach is powerfully connected to the various demographics that exist within ethnic groupings and that taking a polymedia communication strategy will broaden the reach of any sort of messaging.

5.2 Relevance: Connecting with Communities of Interest

Even if a disaster message has reach into communities of interest, it is unlikely to be taken seriously and incorporated into people’s lives unless it is seen as relevant to them. Within the study, we define relevance as the degree to which any communication is seen as having significance and applicability to the target audience.

For many participants, there was a sense that disasters will not happen to them. Whilst New Zealand’s capital of Wellington (positioned on a major fault line) and Christchurch (a city that experienced devastating earthquakes in 2011) were identified as places where natural hazards were likely to occur and disaster knowledge was relevant, this was not so much the case in Auckland.

I’ve experienced floods in Wellington but not in Auckland. (Samoan, male)

We don’t have a legit plan in place. (Samoan/Niuean, female)

Secondly, there was also a sense from many participants that God would take care of them in a disaster, which makes the urgency or importance of being prepared less relevant.

It’s the love of God [that helps us to cope in disasters]. (Samoan, female)

As Pacific Islanders, you know, we know nature and we’re not so stressed about that [disasters]. We trust that He [God] will look after us and we know what to do when the time comes. (Tuvaluan/Kiribatian, female)

Importantly, these leaders acknowledged that everyday livelihoods powerfully relate to people’s interests in disasters. This is reinforced in another study (Masaki 2015, p. 77) where a participant stated, “Pacific people in New Zealand […] are more concerned […] about where their next meal is coming from. That kind of preoccupies a lot of their priorities”.

Participants also emphasized that disasters in the Pacific are disasters in Auckland. Such events provided a relevant entry to think about disasters in Auckland, and participants expressed confidence that their communities would know what to do in an emergency through previous lived experiences of disasters in the Pacific.

As an islander in the community, we kind of do that [disaster response] naturally by instinct already […] I wouldn’t say we have measures in place specifically for natural disasters but I do sort of bank on the fact that if something were to happen to someone in our community people would just come together and know immediately what to do […] It is something we are really good at. (Cook Islander/Ni-Vanuatu, female)

Samoan people are pretty practical and they learn how to adapt and survive. (Samoan, male)

Masaki (2015) also found that churches in Auckland often organize relief efforts following disasters in various parts of the Pacific. It is noteworthy in this context that some of the very first Pacific migration waves to New Zealand in the 1950s and 1960s were triggered by devastating cyclones that caused tremendous destruction in Niue, then Western Samoa and Tokelau (Dunsford et al. 2011).

However, not all island nations experience disasters. For these groups, trying to find relevant entry points may be different.

Kiribati is quite immune from natural disasters like hurricanes and cyclones […] We are quite safe in that. (Kiribatian, male)

This speaks to the need to be aware of differences between distinct Pacific communities with respect to their capacities to respond to disasters based on previous experience. Potentially, the knowledge that some Pacific communities have about disasters can be leveraged to inform disaster risk reduction plans in other places.

5.3 Receptiveness: Building Culturally Resonant Messages

Once a disaster message has reach into particular communities or groups and is seen as relevant to them, there is a need to consider if there is receptiveness to it. We define receptiveness as the degree to which engagement is done in ways that are seen as culturally resonant.

Our culture is very structured and very hierarchal but whether you like it or not, that’s the way things are. If you try to break that part of the structure, the whole thing will fall apart. (Tongan, male)

The Pacific community like face-to-face interaction. It can be quite hard to convey a message over Messenger or texts. But with the Pasifika community, they like the authenticity. (Samoan, male)

Most participants suggested that there was a need for professionals working in disaster risk reduction to speak with their communities, often in conjunction with a trusted leader. This combination of “authoritative knowledge” along with trust would help to make community members more receptive to the associated messaging. They stated that if the leaders saw disasters as relevant and authorities were willing to work alongside them to deliver the message that this would make communities far more receptive.

We need professional advisers to come and give talks. […] If a professional comes and gives a talk, people will listen. (Samoan male)

This also requires working with the cultural structures of these communities that calls for an understanding of hierarchy, power, religion, and traditional practices.

Churches for a lot of Samoan people [are] sacred place[s] and they are very wary of who gets up to speak especially someone from outside the community. (Samoan, male)

If you can get someone on board that relates and understands their cultural values I think they’ll have a pretty good chance in engaging with them. (Tongan, female)

I think verbal communication such as leaders out in the community relaying information to Samoans, or Samoan leaders or translators on TV relaying information—those are the best way to getting information to our people. (Samoan, female)

Ensuring that communities are receptive to any disaster messaging or support can also establish responsive cultural protocols and practices. Several respondents mentioned how post-disaster relief efforts would need to respect certain tapu (taboos), for example when accommodating people in a communal evacuation center.

From a cultural perspective, a sister and a brother can’t sleep together in one area and those things need to be factored in, in terms of planning for natural disaster. (Tongan male, older)

A number of participants emphasized the need to deliver disaster-risk information in face-to-face encounters and in Pacific Island languages. This is where collaborating with key gatekeepers can assist with developing trust and understanding.

I think the severity of a natural disaster is downgraded when you say it in English to older people. So, if you say a warning in Tongan that a disaster could happen, people will be like “oh my gosh, this is so serious.” (Tongan, female)

Many participants noted that humor was an important approach to make people receptive to disaster messaging, by finding the balance of delivering content that did not induce panic but was also provided in a fun and engaging way.

Have a bit of island humor, sort of try to use that humor just to get to the point. (Tongan, male)

However, context is important here. Whilst humor was noted as important, other participants also cautioned that it could be inappropriate in some settings such as church. Thus, the receptiveness of any message needs to take into account the setting in which it occurs. For instance, the study demonstrated some significantly different perspectives about the roles of young people for disaster risk reduction. The older participants generally emphasized that young people did have a place to engage.

The best people to go back to is the young population. We have a saying in Tuvalu [that youth] are our “lima malosi.” They’re our strong hands. (Tuvaluan/Kiribatian, female)

[…] I always talk about in the community that we need to allow the young leadership to grow and develop naturally. […] Most of the Pacific young generation are very smart. They know how to articulate issues and they understand policy and they can write, and those things we need to understand that our children can do things much more efficiently than us. (Tongan, male)

We got a very youthful population so it’s good to know that there are teenagers and young kids who may know more through schooling in how to deal with disastrous events. (Samoan, female)

But the younger participants expressed their frustration about their lack of voice in community affairs. They noted how traditional power structures and hierarchies can prevent the younger Pacific community members from engaging and taking leadership roles. There was also mention of the patriarchal character of Pacific community leadership and potential competition about who would assume leadership roles in case a disaster strikes.

[…] our leaders are elders. They’re from a different world, a different time. […] but I do believe we do need to have a voice as well in there […]. They [young people] don’t engage because they know [they] are going to be shut down by the older people. (Tuvaluan/Kiribatian, female)

[If a disaster hit Auckland] the most dominant male would take charge and there’s a lot of them in my neighborhood so they’ll probably just fight. (Samoan/Niuean, female)

A challenge, therefore, lies in ensuring best practice within particular cultural protocols, but also involves looking for ways to be inclusive to improve the reach of any associated message. In this sense, gatekeepers are critical resources to ensure that messaging is received effectively, although it is also necessary to recognize how this can also create barriers to wider engagement with some groups within a given community.

5.4 Relationships: Connecting Individuals and Communities

The final R relates to relationships. Although all the associated Rs presented are associated with one another, the awareness of relationships is particularly important to the other three categories. All participants noted the need for trust—what sources of information do you trust and from whom—as a critical component of disaster risk reduction. Within this section, we discuss relationships among community members, across communities, and between community and disaster professionals. Relationships here are defined as the way in which two or more people or things are connected, or the state of being connected. The Samoan and Tongan concept of va is highly relevant in this context. Va is often translated as “relationship,” yet some scholars have argued that the word “relatedness” provides a more accurate translation, which points to the relational space that exists not just among human beings but also between people and land, kinship, and even the cosmos (Aiono-Le Tagaloa 2003; Reynolds 2016). Hence, va is a holistic concept that has physical, sociocultural, and religious dimensions.

Most participants noted that their communities would look to, and for support from, their own intraethnic communities:

We live in an extended family, most of our families—our ´aiga—we live in extended families. We are united as families, blood to blood. And that’s why we should always think and [show] concern for one another, especially at times of difficulty and natural disaster. (Samoan, male)

I think the greater strength of the Pacific community is definitely their values of family, respect, reciprocity, collaboration, and being very tight knit. (Samoan, male)

Yet, some Pacific communities are also experiencing internal divisions, often reflecting a political divisiveness in their home islands. Apparently, this affects the bonding social capital within these communities.

I don’t think everyone is well connected. I know that’s because not everyone knows what’s happening in the community. You know there can be an initiative happening in West Auckland and I would never know about it. (Tongan, female)

Some of the respondents mentioned how they were able to connect with other Pacific communities (bridging social capital) and how this could help in the event of a major disaster. The high degree of intermarriage across Pacific nationalities of origin also seems to play a role here, pointing to an increasing fluidity in Pacific identities.

We do have the capability to associate with the other ethnic groups. (Tokelauan, male)

I’m more connected with my Cook Islands side here in Auckland but more connected with my Vanuatu when I’m in the islands. (Cook Islander/Ni-Vanuatu, female)

Looking at the relationship with disaster support organizations (linking social capital), the majority of participants did not know what these organizations would be or who would respond. Some respondents had a vague idea about certain government institutions, such as the police, but emphasized that the relationship with other organizations was not there. Smaller Pacific communities, in particular, expressed concerns that they are overlooked by government agencies:

I don’t think I could rely on disaster relief agencies and local authorities to relay information to the Samoan community. Therefore, Samoans need to be self-sufficient and prepared. (Samoan, male)

We are a minority group here in Auckland. I can’t see that we are recognized by the government. (Tokelauan, male)

Several respondents emphasized the need for Pacific communities to become more proactive in articulating their specific needs with regard to disaster risk information to institutions like the Auckland Council and Auckland Emergency Management and in forming committees in the event of a disaster.

I don’t think the Council and the government could be able to move on our needs if we don’t communicate those needs to them. (Kiribatian, male)

If there is a disaster in Auckland, our community will meet and form a committee and that committee would work with the authorities. (Tongan, male)

Having an awareness of the other 3Rs could be helpful, since considerations of reach, relevance, and receptiveness can go a long way to promote trust within Pacific communities. As the va between structures/agencies and communities is strengthened, this provides fruitful areas in which to look for effective DRR.

6 Discussion: The 4Rs as a Conceptual Framework

As urban environments continue to be shaped by conditions of superdiversity, or the diversification of difference, there is an increasing urgency to ensure that disaster communications are effective across a range of social locations and identities. The concepts of the 4Rs (reach, relevance, receptiveness and relationships) provide a flexible conceptual framework to think through the complexities of delivering effective messaging across the disaster 4Rs (disaster reduction, readiness, response, and recovery; see Fig. 1). Although reach, relevance, receptiveness, and relationships are interrelated, these are not subsumable. In the following, we discuss the implications of these 4Rs as they relate to generating inclusive spaces that foster DRR.

Figure 1 emphasizes the need for greater involvement in DRR planning so that communities understand the associated risks and that any perceived disaster risks match the actual hazardscapes of a given locality. Reach is important to ensure that the communities potentially affected receive the associated message. Once this is achieved, it is necessary that the risks associated with potential disasters are relevant to them. Participation and engagement can be more difficult for those who struggle to sustain a daily living highlighting how everyday inequalities can exacerbate vulnerabilities to disasters (Blake et al. 2017). While disaster messaging will likely have a specific focus, recognition of the broader contexts in which people are living their daily lives has powerful influence on: (1) whether messages will reach them through various media; and (2) if communities will even see them as relevant in relation to perceived risk and the balance of competing priorities.

Provided that the associated message has reach and relevance, it must be delivered through ways in which a community is receptive. This includes the importance of inclusive and culturally responsive social spaces and activities (such as churches, schools, and so on) as acceptable sites for delivering support and the sharing of information. Each of these different contexts that establish receptiveness may mean that the associated reach and relevance will require different approaches. The use of community speakers and message delivery in particular languages and with humor may be received differently at a cultural celebration than at a religious service, for instance. Availability of cross-cultural consultants who can advise on the dynamic nature of receptivity can help navigate the various options of communicating DRR.

An awareness of these Rs also requires the recognition of fragmentation and boundaries and therefore a nuanced understanding of relationships. A community may not see itself necessarily as one. The ethnonational identifier of Samoan, for instance, may powerfully relate to a number of people in a community, but it may not do so for others. The same can be said of leadership—it may appear that a community has a clear leader and spokesperson, but internal dynamics and politics may present a much more complex picture. Leadership may be principally defined by traditional structures and age, but it can also exist alongside other identifiers such as class, geographic location, and even visa status. This nuanced context highlights the need to pay attention to how leadership in Pacific communities is established and legitimized, but also how it is shifting. The awareness of potential fragmentation and boundaries highlights the need to build relationships, and to think about the ways in which disaster planning across reduction, readiness, response, and recovery can most effectively be implemented in settings that are empowering and inclusive.

Across minority communities, gatekeepers can act as the primary or only linguistic link, translating and interpreting disaster information. Young people in particular can fulfil this bridging role due to their linguistic capital and digital literacies, acting as important cultural brokers and as a vital resource that links decision makers with networks and contributes to resilience (Marlowe and Bogen 2015). These gatekeepers are not neutral agents in the flow of information, however, as information is then filtered for relevance and passed on only when trusted (Shepherd and van Vuuren 2014). Thus, thinking through how reach, relevance, receptiveness, and relationships relate to one another in dynamic and contextual ways provides a basis to strategically focus disaster communications with minority groups.

Urban environments characterized by superdiversity require a more nuanced understanding of disaster communication from an essentialized or monolithic perspective of culture. Migration, changing demographics, online communities, inequality, and other factors characterize the complexities of communicating with minority communities in diverse localities. The three typologies of social capital—bonding, bridging, and linking—can be instructive in developing a sense of how disaster messaging can leverage existing forms of capital and identify areas in which to build capacity and additional support. This study highlights the importance of a polymedia communication strategy, and suggests how mobile phones can play an integral role in people’s communication. Nevertheless, our study also emphasizes that community connectedness is likely to be even more important. Included in this approach are the connections that agencies have to particular communities (as a form of linking capital).

Social capital is embedded in social networks and generates positive collective value such as community resources, networks, and trust. The embedded pillars framework that surrounds the 4Rs of disasters in Fig. 1 provides a guiding structure within which to consider the who, what, when, where, and why of disaster messaging. It is relational, contextual, political, and cultural. A communication strategy around disaster readiness will have different considerations than strategies that occur in a response or recovery phase. In all cases across a disaster life span, the embedded framework offers the basis to consider this complexity. The messenger can be as important as the message. The delivery can determine whether people are willing to embrace it or not. In relation, we provide some final recommendations that relate to the Pacific Island communities in Auckland specifically, but we also suggest that these have conceptual applicability in other contexts. These suggestions are as follows:

-

(1)

Engage with these communities when disasters occur in the Pacific.

At the time of writing this article, three severe tropical cyclones travelled through the Pacific Islands. Many Pacific people maintain an ongoing relationship and connection with their cultural heritage and genealogy. Working with community leaders to discuss disasters in Auckland when these disasters occur helps to foster a sense that disasters are relevant to them and that these events could happen where they live. This approach could also provide opportunities for Pacific people living in New Zealand to help inform approaches to support to affected Pacific countries in terms of the delivery of aid and more effective reconstruction initiatives.

-

(2)

Develop a polymedia communication strategy.

Radio, Facebook, and community workshops represent a number of strategies to engage various groups. Community is a not a homogenous concept when one looks at the unique dynamics, contexts, and relationships that exist. This means working with established elders and leaders and emerging young leaders to determine the various ways that a disaster message can be delivered. It might require delivering workshops in languages spoken by communities (this may also be a way to reach those who might not have a valid visa to be in New Zealand) and across church-based groupings.

-

(3)

Proactively develop potential messages and make these texts community driven and agency supported.

Risk communication messages should be tested extensively before crises, particularly amongst communities labelled as at-risk and hard-to-reach (Infanti et al. 2013). Gathering knowledge about the specific needs and diversity of these groups is important. For example, if there is low literacy in their own language, direct translation from English will have limited efficacy. As these specific contexts and social dynamics are better understood, professionals tasked with engaging diverse communities can tailor messaging in ways that ensure it has reach, relevance, receptiveness, and takes at the core of such initiatives the relationships that foster trust and engagement. At the time of writing this article, the authors are working with the Auckland Emergency Management to use this framework to help inform disaster communications during Pacific Island language week events that occur with different communities throughout the year. These events are supported by the Ministry for Pacific Peoples and represent a promising opportunity to strengthen relationships and deliver important messages to diverse Pacific communities across the Auckland region.

A strengths-based approach recognizes resilience and allows agencies to draw on a community’s competencies and cultural resources, utilizing these assets in proactive disaster planning (Tierney 2014; Guadagno 2016). Mathbor (2007) notes how people can be considered experts by experience. Using these knowledges and skills can help ensure that disaster messaging is accessible and acceptable to target groups. As Luna (2009) argued, the need to consider vulnerability should shift from labels to layers. This means recognizing possible vulnerabilities but also recognizing the capacities of communities and agencies to help remove layers of potential vulnerability. These perspectives help to identify existing forms of social capital in communities and where further capacities are needed. When this is done, the people for whom any disaster communication is intended for are more likely to receive and embrace its message.

7 Conclusion

Governance approaches for hazards and disasters are nested within and influenced by broader societal pressures and institutional mandates. Rapid growth and urbanization alongside societies characterized by rich cultural and linguistic diversity present challenges for disaster governance and communication. Considering the ways in which reach, relevance, receptiveness, and relationships can inform the contexts in which this diversity occurs in particular geographic localities can result in meaningful public participation in decision making. It also can go a long way to ensuring that disaster risks can be minimized, or perhaps removed, by ensuring that disaster messaging is trusted and embraced by ethnic minority groupings and people who identify with a range of social locations where understandings of context are so important.

Notes

The categories “reach” and “relevance” may resemble categories that have been developed in marketing and branding. However, this resemblance is coincidental, as our categories have been developed inductively from the data.

References

Aiono-Le Tagaloa, F. 2003. Tapua’i: Samoan worship. Apia, Samoa: Malua Printing Press.

Aldrich, D.P. 2012. Building resilience: Social capital in post-disaster recovery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Auckland Council. 2015. Pacific peoples in Auckland: Results from the 2013 Census. Economic and Social Research and Evaluation Unit. Auckland. http://temp.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz. Accessed 3 Mar 2018.

Auckland Council. 2017. Translating for a diverse Auckland: A guide to decide how and when to translate. Auckland: Auckland Council.

Barclay, J., K. Haynes, T. Mitchell, C. Solanda, R. Teeuw, A. Darnell, H.S. Crosweller, P. Cole, et al. 2008. Framing volcanic risk communication within disaster risk reduction: Finding ways for the social and physical sciences to work together. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 305: 163–177.

Blake, D., J. Marlowe, and D. Johnston. 2017. Get prepared: Discourse for the privileged? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 25: 283–288.

Court, D., and R. Abbas. 2013. Whose interview is it, anyway? Methodological and ethical challenges of insider–outsider research, multiple languages, and dual-researcher cooperation. Qualitative Inquiry 19(6): 480–488.

Covello, V., R. Peters, J. Wojtecki, and R. Hyde. 2001. Risk communication, the West Nile virus epidemic, and bioterrorism: Responding to the communication challenges posed by the intentional or unintentional release of a pathogen in an urban setting. Journal of Urban Health 78(2): 382–391.

Dunsford, D., J. Park, J. Littleton, W. Friesen, P. Herda, P. Neuwelt, J. Hand, P. Blackmore, et al. 2011. Better lives: The struggle for health of transnational Pacific peoples in New Zealand, 1950–2000. Research in Anthropology & Linguistics, Monograph No. 9. Auckland: The University of Auckland.

Eisenman, D., S. Cordasco, S. Asch, J. Golden, and D. Glik. 2007. Disaster planning and risk communication with vulnerable communities: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. American Journal of Public Health 97(S1): 109–115.

Gonzalez-Muzzio, C., and V. Sandoval Henriquez. 2015. Resilient responses from communities and companies after the 2010 Maule earthquake in Chile. UNISDR: A 2015 Report on the Patterns of Disaster Risk Reduction Actions at Local Level. https://www.unisdr.org/campaign/resilientcities/assets/documents/privatepages/Resilient%20responses%20from%20communities%20and%20companies%20after%20in%20Chile.pdf. Accessed 27 Oct 2018.

Guadagno, L. 2016. Human mobility in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 7(1): 30–40.

Infanti J., J. Sixsmith, M. Barry, J. Núñez-Córdoba, C. Oroviogoicoechea-Ortega, and F. Guillén-Grima. 2013. A literature review on effective risk communication for the prevention and control of communicable diseases in Europe. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

Kuhlicke, C., and A. Steinführer. 2012. Social capacity building for natural hazards: Toward more resilient societies. Braunschweig, Germany: European Commission. https://cordis.europa.eu/result/rcn/196511_en.html. Accessed 1 July 2018.

Lee, H. 2009. Pacific migration and transnationalism: Historical perspectives. In Migration and transnationalism: Pacific perspectives, ed. H. Lee, and S.T. Francis, 7–41. Canberra: ANU E Press.

Lilomaiava-Doktor, S. 2009. Samoan transnationalism: Cultivating “home” and “reach”. In Migration and transnationalism: Pacific perspectives, ed. H. Lee, and S.T. Francis, 57–71. Canberra: ANU E Press.

Luna, F. 2009. Elucidating the concept of vulnerability: Layers not labels. International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics 2(1): 121–139.

Macpherson, C., and L. Macpherson. 2009. Kinship and transnationalism. In Migration and transnationalism: Pacific perspectives, ed. H. Lee, and S.T. Francis, 73–90. Canberra: ANU E Press.

Marlowe, J. 2015. Belonging and disaster recovery: Refugee background communities and the Canterbury Earthquakes. British Journal of Social Work 45(S1): 188–204.

Marlowe, J., and R. Bogen. 2015. Young people from refugee backgrounds as a resource for disaster risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 14(2): 125–131.

Masaki, H.T. 2015. Exploring climate change, gender and transnationalism: Perspectives of Pacific women in Auckland. M.A. thesis, Development Studies, The University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Mathbor, G. 2007. Enhancement of community preparedness for natural disasters. International Social Work 50(3): 357–369.

Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management. 2018. “The 4Rs”. https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/cdem-sector/cdem-framework/the-4rs/. Accessed 12 May 2018.

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2018. U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters: Overview. NOAA. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/. Accessed 8 Nov 2018.

Putnam, R. 2000. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. London: Simon & Schuster.

Reynolds, M. 2016. Relating to Va: Re-viewing the concept of relationships in Pasifika education in Aotearoa New Zealand. AlterNative: An International Journal for Indigenous Peoples 12(2): 190–202.

Saldaña, J. 2009. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. London: Sage.

Shepherd, J., and K. van Vuuren. 2014. The Brisbane Flood: CALD gatekeepers risk communication role. Disaster Prevention and Management 23(4): 469–483.

Stats NZ. 2018. 2013 Census. http://archive.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census.aspx. Accessed 28 June 2018.

Tierney, K. 2014. The social roots of risk: Producing disasters, promoting resilience. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Vertovec, S. 2007. Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies 30(6): 1024–1054.

Wylie, S. 2012. Best practice guidelines: Engaging with culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities in times of disaster. Christchurch, NZ: Community Language Information Network Group (CLING).

Acknowledgements

The research for this project received funding from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) under the National Science Challenge No. 11: “Responding to Nature’s Challenges.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Marlowe, J., Neef, A., Tevaga, C.R. et al. A New Guiding Framework for Engaging Diverse Populations in Disaster Risk Reduction: Reach, Relevance, Receptiveness, and Relationships. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 9, 507–518 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-018-0193-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-018-0193-6