Abstract

Like other subjects, disaster risk science has developed its own vocabulary with glossaries. Some keywords, such as resilience, have an extensive literature on definitions, meanings, and interpretations. Other terms have been less explored. This article investigates core disaster risk science vocabulary that has not received extensive attention in terms of examining the meanings, interpretations, and connotations based on key United Nations glossaries. The terms covered are hazard, vulnerability, disaster risk, and the linked concepts of disaster risk reduction and disaster risk management. Following a presentation and analysis of the glossary-based definitions, discussion draws out understandings of disasters and disaster risk science, which the glossaries do not fully provide in depth, especially vulnerability and disasters as processes. Application of the results leads to considering the possibility of a focus on risk rather than disaster risk while simplifying vocabulary by moving away from disaster risk reduction and disaster risk management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Disaster risk science, as with many other subjects, is replete with jargon developed with, by, and for a combination of practitioners, policymakers, and academics. Terms, definitions, and interpretations continually evolve, with original intents and foundational ideas frequently being masked. Some words and phrases are used with limited analysis regarding what they aim to convey and what they actually do convey.

Other primary disaster risk science vocabulary has received detailed attention in this regard, such as “disaster” and “resilience.” Although definitional consensus has not been reached, and might not be feasible or desirable, the literature and debates are extensive. The core idea of “disaster” has been interrogated for decades in books (Quarantelli 1998; Perry and Quarantelli 2005) and other publications (Ball 1979; Quarantelli 1985). The literature has also long sought to reconcile differing vocabulary such as “disaster,” “emergency,” “civil disturbance,” “catastrophe,” “calamity,” and other synonyms (Warheit 1976; Britton 1986; de Boer 1990; Leroy 2006). Less common phrases have entered common usage when adopted by governments, such as UK legislation referring to “civil contingencies” (House of Commons 2004).

Meanwhile, “resilience,” sometimes referred to as “resiliency,” has been extensively deconstructed (Timmerman 1981; Aven 2011; Alexander 2013; Lewis 2013; Sudmeier-Rieux 2014; Etingoff 2016), especially possible meanings and applications from engineering, ecology, and psychology. “Risk,” too, already has a broad literature that discusses, debates, and critiques definitions and meanings across numerous fields (Head 1967; Hansson 1989; Adams 1999; Aven 2010, 2011), although “disaster risk” as a separate concept is less explored in depth.

This article investigates core disaster risk science vocabulary that has not received as much attention in terms of exploring meanings, interpretations, and connotations. The phrases are: (1) hazard; (2) vulnerability; (3) risk, focusing on disaster risk rather than risk in general; and (4) disaster risk reduction (DRR) and disaster risk management (DRM) in tandem given the two phrases’ similarities and connections. The focus is on how definitions have changed and the subsequent implications for understandings of disasters and disaster risk science. The focus is not on etymology, because current professional meanings can differ remarkably from the linguistic origins, as with “resilience” (Alexander 2013). The scope of this article is disaster risk science, rather than a cross-disciplinary comparison such as with environmental epidemiology (Kreis et al. 2013) that can use similar vocabulary with different meanings than disaster risk science. Additionally, this article examines only English, recognizing the disadvantages of this “Anglophone squint” (Whitehand 2005; Stiftel and Mukhopadhyay 2007) and the insights that could be gleaned by comparing vocabulary and interpretations across languages and cultures.

For instance, “hazard” is, to some extent, a peculiarly Anglophone word. In many other languages, the concept does not exist, so it tends to be translated as “danger,” such as in Norwegian (fare, a word also used for “risk” despite the word risiko being common) and French (danger). French accepts aléa as the less common but consensus word that directly means “hazard,” despite its connotation of “aleatory” (in French, aléatoire) that diverges from the English understanding of “hazard” relating to a potential, but not randomness per se. French also has the common word hasard connoting chance or randomness, as in “coincidence,” which is much closer to the English meaning of an aleatory event. French’s hasard is the etymology for the same word in Norwegian meaning a game of chance, but it is rarely used now.

Spanish uses amenaza (threat) in addition to peligro (danger) for “hazard.” In Latin America, amenaza is used for both “potential threat” that might cause damage and “real, physical event” that does cause damage. Given these complications requiring more depth to explore different cultural and linguistic interpretations, especially non-Indo-European ones (see also Bankoff 2001), the focus on English here emphasizes one of the most used languages in disaster risk science and avoids too broad a scope for a single article.

The linguistic differences are not just in translation and interpretation, but are also cultural. In Kelman et al. (2017), Allan Lavell is quoted giving a perspective from Latin America that was established mainly in Spanish but that is now applied in Portuguese for Brazil and, to an increasing extent, in English and French within and outside of the region. Lavell effectively places DRR as a subset of DRM. He explains that DRM provides the scoping, framing, and methodology within which DRR and related activities occur. In essence, a culture has been created establishing a relationship between DRR and DRM. Definitions are created, adjusted, and interpreted within this cultural construct—as must occur since so much of language and vocabulary is adopted and applied through cultural lenses. The main consequence for this article is that the discussions not only are confined to English, but also represent an Anglophone cultural view of disaster risk science.

The next section describes and analyzes the disaster risk science vocabulary of hazard, vulnerability, (disaster) risk, and DRR alongside DRM. Then, the implications for understanding disasters and disaster risk science are reviewed. The conclusions suggest ways forward for risk science vocabulary in future debate and discussion.

2 Disaster Risk Science Vocabulary

The United Nations (UN) produces glossaries to standardize vocabulary for policy and practice. Researchers and others frequently adopt these glossaries to ensure that science is useful and useable in practice. For disaster risk science, two UN secretariats have been the foci. First, from 1990 to 2000, the secretariat of the UN International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction (IDNDR) was the main one and it produced a glossary of agreed terms (UNDHA 1992). Then, at the end of IDNDR, the secretariat for the UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (ISDR) was founded and was later renamed the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, but retained the ISDR acronym.

For ISDR (see UNISDR 2015a), the agency’s first main glossary was published in 2002 but was superseded following feedback that led to a revised version (UNISDR 2004). Major revisions were published after five years (UNISDR 2009) and 13 years (UNISDR 2017). These four glossaries form the core material for examining the progression of key definitions (see also UNISDR 2015a). Many publications from IDNDR and ISDR included their own glossary, either repeating IDNDR’s or ISDR’s main terms or including specialized vocabulary related to the topic under discussion, from hydrology to warning systems. Other UN-related glossaries such as Comité National Japonais (1994) provide only translations of terms without providing definitions.

2.1 Hazard

The definition of “hazard” from UNDHA (1992, p. 44) is “A threatening event, or the probability of occurrence of a potentially damaging phenomenon within a given time period and area.” The focus on “event” or “phenomenon” would seem to exclude many hazardous processes, such as creeping environmental changes or creeping environmental processes/phenomena, defined as slow-moving changes to the environment cumulating in large-scale problems that are often not noticed or acknowledged until a threshold has been passed, leading to a disaster or crisis (Glantz 1994, 1999).

The same issue arises for the UNISDR (2004, vol. II, p. 4) definition of “hazard” as “A potentially damaging physical event, phenomenon or human activity that may cause the loss of life or injury, property damage, social and economic disruption or environmental degradation.” Nevertheless, the inclusion of “activity” moved from a delineated notion such as “event” or “phenomenon” to accepting that not all hazards clearly manifest “within a given time period and area” as in UNDHA (1992). Removing concepts of space and time from the definition generalizes it, acknowledging that hazards are diverse and might not always be easy to parameterize.

UNISDR (2009, p. 17) retained the same basic concepts and almost the same text, with “hazard” defined as “A dangerous phenomenon, substance, human activity or condition that may cause loss of life, injury or other health impacts, property damage, loss of livelihoods and services, social and economic disruption, or environmental damage.” The addition of “condition” further strengthens the definition by emphasizing that not all hazards are easily delineated events or phenomena.

This point became even more explicit in UNISDR (2017, online) defining “hazard” as “A process, phenomenon or human activity that may cause loss of life, injury or other health impacts, property damage, social and economic disruption or environmental degradation.” Here, the word “process” is included to support hazards being dynamic through time and over space, such as creeping changes. The word “dangerous” is excluded, perhaps recognizing that “danger” and “hazard” have differences in English.

One component retained throughout the definitions is that the hazard’s origin can be anthropogenic. This aspect is implicit with UNDHA (1992), but explicit in the three definitions from UNISDR (2004, 2009, 2017). This point is important in understanding from where disasters arise because some environmental processes and phenomena have hazardousness augmented due to human interventions. For river floods, dredging and building levees can increase parameters such as depth and speed, making any flood more hazardous, as witnessed in parts of the Mississippi River basin (Criss and Shock 2001). Many earthquakes are caused by human action including fracking, reservoirs, groundwater extraction, fossil fuel extraction, and nuclear tests (Ellsworth 2013). Urbanization affects wind speed and air temperature, exacerbating heat wave hazards in particular (Clarke 1972). The definitions of “hazard” accept that hazards might be entirely from nature (for example, a meteorite (unless it becomes a weapon in future wars)), entirely from human activity (for example, pollution), or a combination (for example, flood depth and speed augmented by channeling rivers).

The definitions also speak to the social construction of hazard viewpoint, in that some hazards might not be hazardous unless they interact with society, while hazardousness can be a function of this interaction. Rain is an essential environmental phenomenon for human and other life. Rain coming into a house through an open window has hazardous properties when falling on carpets and computers. If rain enters an open window and causes computer and carpet damage, is the hazard the rain, the open window, or the decision to leave damageable property beside an open window when it might rain? The carpet and computer themselves represent vulnerability (or exposure), discussed in the next section.

By analogy, if a housing development without earthquake resistance measures is approved in a known seismic zone, is the hazard the earthquake fault, the earthquake, the lack of seismic resistance measures in the buildings, or the decisions for planning, development, and construction? Again, the actual buildings represent vulnerability (or exposure). By analogy, a person falling off the roof of a tall building without any mitigating measures reveals gravity followed by the consequences of hitting the ground at a high speed. Is the hazard gravity, a hard landing, falling off the roof, a tall building, the lack of mitigating measures, or a combination? As with rain being useful, so is gravity and perhaps even earthquake faults in terms of bringing water to the surface in arid regions (Jackson 2001). For the latter, is the earthquake fault a hazard in itself or does hazardousness require an earthquake? Could tectonic uplift from an earthquake creating land from underwater be considered usefulness or a resource, keeping in mind that earthquakes also subside land below water? The answers to these questions more or less come down to definitions and philosophical renderings, meaning in effect that hazards and hazardousness are largely social constructions.

Yet the environmental phenomena or processes—such as rain, gravity, earthquake faults, and earthquakes—have materialities, energies, and forces irrespective of potentially being hazards to and resources for society simultaneously. They are resources for society only because people use them, such as for drinking and irrigation. They might sometimes be hazards because human activity makes them hazardous to society, just as Hewitt (1997, p. 68) states for biological hazards associated mainly with human activity that “it seems misleading to call them ‘natural’ hazards.” Even where some phenomena and processes originate in the environment, human activity can make them “unnatural hazards.” That is, they are neither natural hazards nor environmental hazards, instead being phenomena with properties that society can make hazardous.

2.2 Vulnerability

UNDHA (1992, p. 77) defines “vulnerability” as “Degree of loss (from 0% to 100%) resulting from a potentially damaging phenomenon.” This definition assumes that vulnerability is calculable and quantifiable, despite much earlier work describing vulnerability as having qualitative aspects and intangible elements (Lewis 1979; Hewitt 1983; see also the discussion of “(Disaster) Risk” in Sect. 2.3).

UNISDR (2004, vol. II, p. 7) adopts many of these scientific lessons, diverging from UNDHA (1992), by defining “vulnerability” as “The conditions determined by physical, social, economic, and environmental factors or processes, which increase the susceptibility of a community to the impact of hazards.” UNISDR (2009, p. 30) then defines “vulnerability” as “The characteristics and circumstances of a community, system or asset that make it susceptible to the damaging effects of a hazard.” UNISDR (2017, online) is similar, but much wordier, by defining “vulnerability” as “The conditions determined by physical, social, economic and environmental factors or processes which increase the susceptibility of an individual, a community, assets or systems to the impacts of hazards.” All three effectively define “vulnerability” with respect to susceptibility but do not define “susceptibility” or variations.

The most prominent difference amongst the UNISDR definitions is that UNISDR (2009) identifies “characteristics and circumstances” while UNISDR (2004) and UNISDR (2017) identify “conditions.” The connotation of “condition” tends to be with respect to mode or state; that is, a snapshot approach to characterize the entity under scrutiny. Aspects of circumstances and reasons for displaying observed conditions might form a secondary layer to the word’s meaning, although this part is more implicit than explicit. This fixed picture view of vulnerability through “conditions” contrasts with “characteristics and circumstances” that directly encompass a snapshot (characteristics) and reasons for those characteristics appearing (circumstances).

The importance of looking beyond a snapshot is demonstrated through understanding vulnerability as a process (Lewis 1979, 1999). The vulnerability process reveals two important points from understandings of vulnerability that are accepted by UNISDR (2009) and then removed from UNISDR (2017) in retrogressing back to UNISDR (2004). First, examining only the current state cannot provide a comprehensive view of vulnerabilities. Part of vulnerability is contextual in relation to aspects around and influencing what is vulnerable, but not necessarily within any specific element. The word “circumstances” indicates that any element must be examined beyond the element itself to understand vulnerability fully.

Second, vulnerability embraces a temporal dimension. Vulnerability is not simply what is observed at the current moment. Vulnerability must also establish how and why the current state was reached: What processes led to the characteristics and circumstances, why was the situation created, what could have happened instead, and what are potential future pathways? UNISDR (2009, p. 30) comments after the definition that “Vulnerability varies significantly within a community and over time,” accepting part of the spatial and temporal contexts of vulnerability as articulated by the vulnerability process (Lewis 1979, 1999; Hewitt 1983, 1997; Wisner et al. 2004). These points are missing from UNISDR (2004, 2017).

Both the 2004 and 2017 definitions, however, accept that processes are important as inputs into the condition of vulnerability. This process idea could have been integrated fully into defining vulnerability, given the long-standing science on this topic—especially when the 2009 definition did include the process idea to some degree.

Another ambiguity emerges with respect to the term “exposure.” Neither UNDHA (1992) nor UNISDR (2004) include the term “exposure.” UNDHA (1992) lists “exposure time” in reference to seismic risk, a different concept. In defining “risk,” UNISDR (2004, vol. II, p. 6) notes “Conventionally risk is expressed by the notation Risk = Hazards × Vulnerability. Some disciplines also include the concept of exposure to refer particularly to the physical aspects of vulnerability.”

UNISDR (2009, p. 15) welcomes “exposure” as a new term now relevant for disaster risk science with the definition “People, property, systems, or other elements present in hazard zones that are thereby subject to potential losses.” For “vulnerability,” UNISDR (2009, p. 30) explains in a post-definition comment, “This definition identifies vulnerability as a characteristic of the element of interest (community, system or asset) which is independent of its exposure. However, in common use the word is often used more broadly to include the element’s exposure,” thereby highlighting the ambiguity of separating vulnerability and exposure.

This nuancing disappears from UNISDR (2017), which presumably assumes that vulnerability and exposure are accepted as being separate and ostensibly independent. For UNISDR (2017, online), “exposure” is “The situation of people, infrastructure, housing, production capacities and other tangible human assets located in hazard-prone areas” with an annotation supposing that exposure, vulnerability, and capacity are quantitative and to be used for calculating quantitative risks.

The idea of exposure could potentially be complementary to vulnerability in that exposure describes what could be harmed by hazards while vulnerability explains why it is in harm’s way. The changes in defining “vulnerability” to diminish thoughts on the “process” might obviate the need for two different terms. From UNISDR’s (2017) definitions, it is not clear that the actual elements existing are separable from those elements’ conditions. The elements and their conditions could easily be combined into a single concept, exactly as UNISDR’s (2004, 2009) definitions do, with exposure being part of vulnerability, thus acknowledging interaction between elements and their conditions.

Buildings can shield each other from hazards. Landslide, flood, and wind parameters frequently diminish after encountering, damaging, or destroying a structure, reducing the hazard’s impact on the structures behind. Whether this situation means that fewer elements are subject to certain hazard parameters (exposure) or that conditions or potential damage differ (vulnerability) is semantics. Conversely, buildings might augment hazard-related damage. Many high-rises in Tokyo are designed to sway during an earthquake in order to avoid toppling. If the earthquake parameters experienced by adjacent high-rises are sufficient, then possibilities might exist for building collisions. Similarly, a collapsing building can damage structures nearby, weakening their ability to withstand subsequent hazards. Whether these situations mean that more elements are subject to certain hazard parameters (exposure) or that conditions or potential damage differ (vulnerability)—or that exposure and vulnerability augment hazard parameters—is again semantics.

Definitions much more rigorous than those supplied by UNISDR (2009, 2017) might be able to separate completely exposure and vulnerability. This separation would be artificial and is not really necessary considering that the point of developing these terms is to understand why disasters occur and to deal with them. A tenet within disaster research has long been that disasters occur due to long-term processes that prevent people from improving their situations, so they end up being adversely affected by events and processes that become hazardous (Lewis 1979, 1999; Hewitt 1983, 1999; Wisner et al. 2004). Interactions amongst conditions, characteristics, and circumstances are as important to disaster-related outcomes as the conditions, characteristics, and circumstances themselves, blending and deepening the ideas behind the definitions of “vulnerability” and “exposure.”

2.3 (Disaster) Risk

In UNDHA (1992, p. 64), risk is defined as “Expected losses (of lives, persons injured, property damaged, and economic activity disrupted) due to a particular hazard for a given area and reference period. Based on mathematical calculations, risk is the product of hazard and vulnerability.” UNDHA (1992) does not define “disaster risk,” but uses the phrase once (p. 18) in defining “acceptable risk” as the “Degree of human and material loss that is perceived by the community or relevant authorities as tolerable in actions to minimize disaster risk.”

UNISDR (2004) also does not define “disaster risk.” “Risk” is “The probability of harmful consequences, or expected losses (deaths, injuries, property, livelihoods, economic activity disrupted or environment damaged) resulting from interactions between natural or human-induced hazards and vulnerable conditions” (UNISDR 2004, vol. II, p. 7). A significant shift is evident from UNDHA (1992). “The probability of harmful consequences” is put on equivalent terms with “expected losses” for which examples are provided. Rather than assuming that risk is calculated as a product, as in UNDHA (1992), risk combines hazard and vulnerability for UNISDR (2004), but how this combination occurs is left open.

UNISDR (2009, p. 25) defines risk as “The combination of the probability of an event and its negative consequences.” “Disaster risk” is defined separately as “The potential disaster losses, in lives, health status, livelihoods, assets and services, which could occur to a particular community or a society over some specified future time period” (pp. 9–10). In effect, “disaster risk” is taken to mean “potential disaster losses,” which could be quantified or not.

UNISDR (2017) no longer presents a separate entry for “risk.” “Disaster risk” becomes much more complicated: “The potential loss of life, injury, or destroyed or damaged assets which could occur to a system, society or a community in a specific period of time, determined probabilistically as a function of hazard, exposure, vulnerability and capacity” (UNISDR 2017, online). “Disaster risk” is still, effectively, potential disaster losses, with a two-part specification. First, risk is defined probabilistically only, eliminating any qualitative approaches. Second, the concepts of “hazard, exposure, vulnerability and capacity” are re-introduced/introduced explicitly into the definition. The apparent separation of exposure, vulnerability, and capacity is not especially in line with earlier discussions (Sect. 2.2). Furthermore, it is unclear whether or not these four variables must be independent or, as other literature indicates, interact.

The change from UNDHA (1992) to UNISDR (2004) removed the assumption of calculation and quantification. This approach is retained implicitly by UNISDR (2009), but the assumption of quantification is reintroduced by UNISDR (2017). UNISDR’s (2009, 2017) definitions of “disaster risk” are generally in line with wider literature, but UNISDR (2009) was far more encompassing than UNISDR (2017) by not forcing quantification and by keeping the vocabulary more clear-cut than UNISDR (2017). The wider literature regarding the definition of “disaster risk” from previous decades of disaster risk science has also not always assumed calculation or quantification and has generally fallen into two principal categories.

First, as with UNDHA (1992), disaster risk is a combination or function of hazard and vulnerability, most notably variations of the mathematical product of hazard times vulnerability. Wisner et al. (2004, p. 45) refer to disaster risk = hazard × vulnerability as a “pseudo-equation” suggesting it as a mnemonic rather than as a meaningful calculation, which matches UNISDR (2004). Wisner et al. (2004) also introduce “capacity” and “mitigation” as reducing disaster risk in the pseudo-equation. Other terms added to the basic hazard-vulnerability product, as an equation and as a mnemonic, are from De La Cruz-Reyna (1996) who places “value (of the threatened area)” in the product, which is then divided by “preparedness,” while Granger et al. (1999) add only “elements at risk” into the product. Peduzzi et al. (2009) apply the latter formulation by specifying “elements at risk” as the number of people experiencing a hazard. In these formulations, “elements at risk” seem to match “exposure,” distinct from vulnerability, as discussed in Sect. 2.2.

The second category, as with UNISDR (2009), explains disaster risk as the combination (sometimes as a product) of the probability of an event and the consequences of the event. For example, it is applied to fire by Hurley (2015), but critiqued by Kaplan and Garrick (1981) who prefer “probability and consequence” rather than “probability times consequence.” “Probability-consequences” parallels “hazard-vulnerability” with “probability” typically interpreted as “probability of a hazard” and “consequences” matching the damage or losses that result or could result due to the hazard. Smith (2013, p. 11) thus concatenates the two definitional groupings by suggesting “disaster risk” as “the likely consequence…the combination of the probability of a hazardous event and its negative consequences.”

The core concept within the definition of “disaster risk” does not really change over time or across different references, referring to overlapping notions of either: (1) possible losses from a hazard; or (2) potential adverse consequences in a disaster. The power of this definition is that various calculative forms are possible along with qualitative interpretations that are precluded by UNISDR’s (2017) definition. Intangible, non-quantitative, non-calculative losses and consequences have long been known to arise from disasters (Butler and Doessel 1980). Damage to natural and cultural heritage exemplify these losses with examples being irreplaceable photos or documents, cemeteries, and species extinctions. Similarly, while casualties are easily quantifiable by counting, the numbers cannot capture the true experience of losing a loved one or dealing with life-changing injuries, so these consequences are sometimes considered to be intangible (Butler and Doessel 1980).

2.4 Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) and Disaster Risk Management (DRM)

UNDHA (1992) does not include the phrase “disaster risk reduction,” although it was entrenched in the literature at the time (Davis and Lohman 1987; Johnson 1987; Vermeiren 1993). Similarly, “disaster risk management” is absent from UNDHA (1992) despite it being used in the field at least a decade before (Reams and Surrency 1982).

UNISDR (2004, vol. II, p. 3) defines “disaster risk management” as “The systematic process of using administrative decisions, organization, operational skills and capacities to implement policies, strategies and coping capacities of the society and communities to lessen the impacts of natural hazards and related environmental and technological disasters. This comprises all forms of activities, including structural and non-structural measures to avoid (prevention) or to limit (mitigation and preparedness) adverse effects of hazards.” This definition is heavily filled with jargon, yet it is forthright that DRM is a process involving human actions to deal with hazards and disasters.

“Disaster risk reduction (disaster reduction)” is defined by UNISDR (2004, vol. II, p. 3) as “The conceptual framework of elements considered with the possibilities to minimize vulnerabilities and disaster risks throughout a society, to avoid (prevention) or to limit (mitigation and preparedness) the adverse impacts of hazards, within the broad context of sustainable development.” This definition is quite clear and sensible, especially in terms of highlighting the need to minimize vulnerabilities while placing DRR within the broader construct of sustainable development. Mentioning “adverse impacts of hazards” recognizes that hazards do not inevitably have only negative consequences—which sits directly within the ethos of UNISDR’s (2004) “living with risk” title. DRR and DRM are delineated by the former being a framework and the latter being actions, although the goal is subtly dissimilar: “minimise vulnerabilities and disaster risks” compared to “lessen the impacts” of hazards and disasters.

Having dropped “disaster reduction,” UNISDR (2009, pp. 10–11) defines “disaster risk reduction” as “The concept and practice of reducing disaster risks through systematic efforts to analyse and manage the causal factors of disasters, including through reduced exposure to hazards, lessened vulnerability of people and property, wise management of land and the environment, and improved preparedness for adverse events.” This definition has a tautology in “disaster risk reduction” meaning “reducing disaster risks.” Otherwise, it is impressive in its elegance and directness, focusing on understanding and addressing “causal factors” while covering all hazards and all vulnerabilities. The examples given of actions strike at the long-established root causes of vulnerabilities and hence disasters. This definition captures the baseline of where disasters arise from, how they should be framed, and how they could be tackled (O’Keefe et al. 1976; Torry 1979; Hewitt 1983, 1997; Lewis 1999; Wisner et al. 2004).

Meanwhile, “disaster risk management” (UNISDR 2009, p. 10) is “The systematic process of using administrative directives, organizations, and operational skills and capacities to implement strategies, policies and improved coping capacities in order to lessen the adverse impacts of hazards and the possibility of disaster.” It seems as if DRM emerges as the operationalization of DRR, especially given that the goal is “to lessen” rather than “to manage.”

UNISDR (2017, online) defines “disaster risk reduction” as “Disaster risk reduction is aimed at preventing new and reducing existing disaster risk and managing residual risk, all of which contribute to strengthening resilience and therefore to the achievement of sustainable development.” An annotation reads “Disaster risk reduction is the policy objective of disaster risk management, and its goals and objectives are defined in disaster risk reduction strategies and plans.” Consequently, in contrast to UNISDR (2009), DRR seemingly emerges from DRM. “Disaster risk management” from UNISDR (2017, online) is “the application of disaster risk reduction policies and strategies to prevent new disaster risk, reduce existing disaster risk and manage residual risk, contributing to the strengthening of resilience and reduction of disaster losses.” Its annotation is “Disaster risk management actions can be distinguished between prospective disaster risk management, corrective disaster risk management and compensatory disaster risk management, also called residual risk management.”

The immediate concern with both these definitions is the amount of other nomenclature, such as “residual risk” and “resilience.” The annotation for DRM includes further terms, namely “prospective,” “corrective,” and “compensatory” DRM, without similar differentiations amongst different forms of DRR. It is laudable that DRR continues to be directly connected to the long-standing sustainable development agenda and, seemingly, is placed directly within it. It loses clarity given that the relationship between resilience and sustainable development has long been explored without resolution or consensus (Gardner 1989; Tarhan et al. 2016).

In the literature, an evolution has occurred in the use of DRR, DRM, and related terms. Initially, these terms were not formally defined in the glossaries. Later, they achieved formal recognition and relatively straightforward definitions. With formal acceptance came increasingly complicated and jargon-filled definitions. It also seems that relationships amongst DRR/DRM terms are set by definitions, rather than any innate or natural relationship existing. Permitting definitions to dictate connections amongst the vocabulary is advantageous in delineating solid, verifiable starting points for each term. When substantive definitional changes occur altering the connections and relationships, as in the change from UNISDR (2009) to UNISDR (2017), confusion can result when earlier documents are rendered obsolete merely due to a choice of words rather than from any inherent meanings.

3 Implications for Understanding Disasters and Disaster Risk Science

Navigating the vocabulary and its interpretations for disasters and disaster risk science is not an easy pathway. First, many of the definitions require an understanding of other concepts, such as “mitigation” and “residual risk.” Second, the development of some of the definitions through each iteration of the glossaries means that older material might be out-of-date by using words that now have a different meaning from when the material was first published. Third, the vocabulary sometimes deviates from the basic, original science of why disasters occur (O’Keefe et al. 1976; Torry 1979; Hewitt 1983, 1997; Lewis 1999; Wisner et al. 2004), many concepts from which have remained remarkably consistent, and so are continually reiterated, in contemporary publications covering similar material (Schuller and Morales 2012; Krüger et al. 2015; Oliver-Smith 2016; Wisner 2017; Mika 2019).

The most poignant lesson echoing across the decades is perhaps the foundational disaster risk science statement that almost all disasters are caused by vulnerabilities, even though both vulnerability and hazard input into disaster risk. No matter what metric is used for disaster, hazard parameters do not necessarily correlate well with disaster outcome (Hewitt 1997). As one example, on 22 December 2003, central California experienced an earthquake of moment magnitude 6.5 at 8 km depth, which killed two people when a clock tower collapsed. Four days later, southeast Iran experienced an earthquake of similar parameters, moment magnitude 6.6 at 10 km depth, yet approximately 25,000 people died. The different outcome from similar hazard parameters is attributed to only vulnerabilities affecting the disaster risk and causing the disaster.

Similarly, Haiti’s 12 January 2010 earthquake disaster was rooted in the decades and centuries of vulnerability creation and vulnerability perpetuation in Haiti, long before the earth shook (Schuller and Morales 2012; Mika 2019). As per evidence from decades of disaster and development research, policy, and practice, there is no disaster without vulnerability and vulnerability is a long-term process. As Lewis (1988, p. 4) writes, “All disasters are slow onset when realistically and locally related to conditions of susceptibility.” The root cause of disasters is vulnerability, which accrues over the long-term based on long-term human values, decisions, and activities. A hazard might be rapid-onset, but the disaster, requiring much more than a hazard, is a long-term process, not a one-off event, so a disaster cannot be rapid-onset (see also Quarantelli 1998; Perry and Quarantelli 2005).

The occurrence of a hazard starkly reveals the ever-present, latent, chronic vulnerabilities that create, cause, and make the disaster (Lewis 1999; Wisner et al. 2004). Without a hazard, the vulnerability does not vanish, hence disaster potential remains and the root cause of disaster waits to be uncovered, if not by DRR and DRM endeavors, then inevitably when a hazard appears. Nor does the disaster stop once the hazard ebbs. In a dimension not captured by the definitions in the UN glossaries, the disaster can continue, or a new one can dominate, due to the post-disaster actions following the initial hazard and disaster.

Oliver-Smith (1979) wrote, “First the earthquake, then the disaster.” His full quotation is “First the earthquake, then the avalanche…and then the disaster” (p. 50), with the ellipses being in the original citation because it represents a pause, not missing words. Oliver-Smith (1979) was writing about the 31 May 1970 earthquake and rock avalanche in Yungay, Peru, describing how shoddy and inequitable relief and reconstruction, including arbitrary relocation plans, caused as much suffering as the initial hazard killing thousands. Oliver-Smith’s mantra and analysis have been repeated and paraphrased in many situations since. For instance, after the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami disaster, many survivors referred to “the second tsunami” of humanitarian workers and their resources inundating the places that the tsunami had flooded, as well as the potential “disaster” of reconstruction expectations not being met (Kennedy et al. 2008).

Collating these points, the result becomes: First the (development) disaster, then the hazard, then the (aid) disaster. That is, first the disaster of shaping, accruing, and perpetuating vulnerabilities, so that a hazard is bound to wreak devastation amongst the vulnerable people, locations, and infrastructure. This process is also termed “disaster risk creation” (Lewis and Kelman 2012). Then, a hazard occurs so that damage and destruction are witnessed. Afterwards, the response, recovery, and reconstruction can be a disaster through mismanaged resources, failure to implement systems that reduce vulnerabilities, and victimizing and exploiting survivors.

Paraphrasing Oliver-Smith (1979), first the disaster, then the earthquake, then the disaster. More to the point of the foundations of disaster risk science and the basic interpretation of its core vocabulary: First the vulnerability, then the hazard, then the vulnerability: This is the disaster.

This disaster story does not apply in all cases. A vast array of examples from around the world demonstrates successes in DRR and DRM (UNISDR 2004; Wisner et al. 2004; Shaw et al. 2009). The basic interpretation of disaster risk science’s core vocabulary then becomes: First the disaster risk creation, then the hazard, then the DRR and DRM—or perhaps if better approaches could be achieved: first the vulnerability, then the DRR and DRM (so avoiding a disaster), then drop the first step of vulnerability creation.

These formulations of what a disaster is and how and why disasters arise are well-established within the UN, such as through UNISDR (2004) and UNDP (2004) as well as the voluntary frameworks of the Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015 (UNISDR 2005) and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (UNISDR 2015b). Therefore, the foundational ideas of disaster risk science could have remained in the UN glossaries, with UNISDR (2004, 2009) mentioning them to a reasonable level, but UNISDR (2017) having drifted away from core aspects. Given that the glossaries include notes, comments, and annotations, ample opportunity existed and exists to clarify key points or to contextualize the choice of definitions. Instead, the trend has been to move away from the most important ideas contained within the literature while generally increasing the length and complexity of the phrases defined.

For instance, with no base in previous glossaries, UNISDR (2017, online) defines the lengthy phrase “Local and indigenous peoples’ approach to disaster risk management” as “the recognition and use of traditional, indigenous and local knowledge and practices to complement scientific knowledge in disaster risk assessments and for the planning and implementation of local disaster risk management.” The approach that joins numerous knowledge forms, treating them all equitably in order to take the best from each of them to support the limitations of each, is well-founded in disaster risk science (Shaw et al. 2009; Balay-As et al. 2018). The literature does not assume that DRM must initially be from external, scientific knowledge meaning that local and indigenous knowledge merely complements it and requires a separate entry. Instead, the disaster risk science view is that DRR and DRM by definition combine multiple knowledge forms. The definitions, notes, annotations, or comments in UNISDR (2017) could have taken this approach instead.

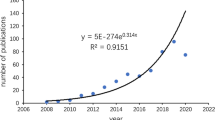

Moreover, UNISDR (2017) explicitly does not account for the full body of disaster risk science knowledge. UNISDR (2015a, p. 2) explains that revisions from UNISDR (2009) to UNISDR (2017) came about by analyzing “about 35,000 documents and existing definitions to identify the usage of the 53 terms on disaster risk reduction proposed by the UNISDR. The results allowed for classification of the 53 terms by frequency of use and ranking for the period 2000–2004, 2005–2009 and 2010–2014.” The only significance of starting with the year 2000 is possibly that IDNDR transitioned to ISDR in that year. The three five-year bins have no obvious significance.

The difficulty with bypassing all pre-2000 material is that foundational works, ideas, explanations, and understandings might not be given full attention (for example, from O’Keefe et al. (1976), Ball (1979), Oliver-Smith (1979), Hewitt (1983, 1997), Britton (1986), Glantz (1994, 1999), and Lewis (1999)). The assumption might be that later work incorporates this earlier material. If this assumption holds, then no reason exists to start at 2000. 2009 would be a more logical starting point, given that UNISDR (2009) was already published and that UNISDR (2017) was updating the 2009 material. As this article has shown, the assumption is incorrect that later work inevitably builds on all earlier work, because key thoughts have been lost or diluted in UNISDR (2017) and were not even fully present in UNISDR (2004, 2009).

4 Conclusions

This article has taken core concepts from disaster risk science—hazard, vulnerability, risk focusing on disaster risk, and disaster risk reduction (DRR) together with disaster risk management (DRM)—to examine their meanings, interpretations, and evolution based on UN glossaries, with implications for understandings of disasters and disaster risk science. Many key words in this topic were not covered and would be suitable for similar analysis, including capacity, capability, adaptation, mitigation, preparedness, readiness, and prevention amongst others. Interactions amongst the concepts, especially how hazard and vulnerability might influence each other, require further examination. Other important areas for research are comparatively analyzing how vocabularies are defined, applied, and interpreted across countries, cultures, languages, and dialects as well as the meanings, or lack thereof, for policy and practice at different scales. In particular, no evidence or discussion is presented in this article to indicate who adopts the definitions, in which contexts, how they are applied, or their relevance for and use in policy and practice.

Nevertheless, in examining the vocabulary here, it appears that, in many cases, seemingly arbitrary decisions are taken about altering definitions and including or excluding phrases and ideas. Even when a systematic attempt is made to choose and define vocabulary, such as UNISDR (2015a), the scoping precludes known and important points from being incorporated directly into definitions (for example, the vulnerability process and the disaster process) while increasing the volume and complexity of the nomenclature included.

Rather than never-ending expansion of glossaries to encompass all possible words and combinations thereof, might an argument be considered for simpler, more straightforward, and more meaningful approaches? Given the perennial debates on differentiating and linking DRR and DRM, two layers of possible simplification could emerge.

First, how crucial is the word “disaster” in these phrases? As described in the introduction, numerous synonyms for “disaster” exist along with long-standing unresolved debates regarding their differentiation and meanings. Does the term “disaster” galvanize action to stop widespread devastation? Does it confuse by creating a silo for disasters that is separate from other risks and people’s day-to-day or lifetime-to-lifetime concerns? UNISDR (2009, 2017) does try to differentiate amongst risk types, for example, extensive and intensive risks, but it is not clear whether the effort clarifies or confuses more. Focusing on “risk” might avoid separation of risk-related fields while providing advantages in connecting knowledge forms, such as analyses of linking low probabilities with people’s daily concerns.

Second, how crucial is it to retain both “reduction” and “management”? In common English, “management” tends to imply any form of action or inaction, thereby encompassing reduction and creation. In theory, (disaster) risk management could mean creating risk. Creating risk is not necessarily detrimental, given how many people do not seek to minimize risk, whether in skiing or financial investments. Similarly, many people are forced, or choose, to accept disaster risk, such as in exchange for volcanic ash farming, water supply from earthquake faults (Jackson 2001), or a gorgeous river view.

If DRR and DRM are to be possibly investigated for phasing out as (disaster) risk science phrases, what would replace them? Perhaps the focus could be back to basics: risk combines hazards (or probabilities) and vulnerabilities (or consequences)—encompassing exposure and so eliminating the need for the “exposure” term. “Hazard,” “vulnerability,” and “risk” still require definitions and discussions. At least they are fewer and simpler terms coming from an existing, foundational literature. They can be used to highlight baseline ideas melding risk science and dealing with disasters (and so into sustainable development), providing a grounding for applying this science for positive action.

References

Adams, J. 1999. Risk. London: UCL Press.

Alexander, D.E. 2013. Resilience and disaster risk reduction: An etymological journey. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 13(11): 2707–2716.

Aven, T. 2010. On how to define, understand and describe risk. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 95(6): 623–631.

Aven, T. 2011. On some recent definitions and analysis frameworks for risk, vulnerability, and resilience. Risk Analysis 31(4): 515–522.

Balay-As, M., J. Marlowe, and J.C. Gaillard. 2018. Deconstructing the binary between indigenous and scientific knowledge in disaster risk reduction: Approaches to high impact weather hazards. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 30: 18–24.

Ball, N. 1979. Some notes on defining disaster: Suggestions for a disaster continuum. Disasters 3(1): 3–7.

Bankoff, G. 2001. Rendering the world unsafe: “Vulnerability” as western discourse. Disasters 25(1): 19–35.

Britton, N.R. 1986. Developing an understanding of disaster. Journal of Sociology 22(2): 254–271.

Butler, J.R.G., and D.P. Doessel. 1980. Who bears the costs of natural disasters?—An Australian case study. Disasters 4(2): 187–204.

Clarke, J.F. 1972. Some effects of the urban structure on heat mortality. Environmental Research 5(1): 93–104.

Comité National Japonais. 1994. Multi-language glossary on natural disasters (Glossaire multi-language sur les désastres naturels). Tokyo: Comité National Japonais pour la Décennie Internationale de la Réducion des Désastres Naturels.

Criss, R.E., and E.L. Shock. 2001. Flood enhancement through flood control. Geology 29(10): 875–878.

Davis, I., and E.J.A. Lohman. 1987. A manual for the implementation of disaster risk reduction measures. Open House International 12(3): 40–42.

de Boer, J. 1990. Definition and classification of disasters: Introduction of a disaster severity scale. Journal of Emergency Medicine 8(5): 591–595.

De La Cruz-Reyna, S. 1996. Long-term probabilistic analysis of future explosive eruptions. In Monitoring and mitigation of volcano hazards, ed. R. Scarpa, and R.I. Tilling, 599–629. Berlin: Springer.

Ellsworth, W.L. 2013. Injection-induced earthquakes. Science 341(6142): 142–149.

Etingoff, K. (ed.). 2016. Ecological resilience: Response to climate change and natural disasters. Oakville: Apple Academic Press.

Gardner, J.E. 1989. Decision making for sustainable development: Selected approaches to environmental assessment and management. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 9(4): 337–366.

Glantz, M.H. 1994. Environmental phenomena: Are societies equipped to deal with them? In Proceedings of Workshop on Creeping Environmental Phenomena and Societal Responses to Them, 7–10 February 1994, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Glantz, M.H. (ed.). 1999. Creeping environmental problems and sustainable development in the Aral Sea Basin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Granger, K., T. Jones, M. Leiba, and G. Scott. 1999. Community risk in cairns: A multi-hazard risk assessment. Cairns: Australian Geological Survey Organisation Cities Project.

Hansson, S.O. 1989. Dimensions of risk. Risk Analysis 9(1): 107–112.

Head, G.L. 1967. An alternative to defining risk as uncertainty. The Journal of Risk and Insurance 34(2): 205–214.

Hewitt, K. (ed.). 1983. Interpretations of calamity from the viewpoint of human ecology. London: Allen & Unwin.

Hewitt, K. 1997. Regions of risk: A geographical introduction to disasters. London: Routledge

House of Commons. 2004. Civil contingencies bill. London: House of Commons.

Hurley, M.J. (ed.). 2015. SFPE handbook of fire protection engineering. New York: Springer.

Jackson, J. 2001. Living with earthquakes: Know your faults. Journal of Earthquake Engineering 5(sup001): 5–123.

Johnson, B.B. 1987. Accounting for the social context of risk communication. Science & Technology Studies 5(3/4): 103–111.

Kaplan, S., and B.J. Garrick. 1981. On the quantitative definition of risk. Risk Analysis 1(1): 11–27.

Kelman, I., J. Mercer, and J.C. Gaillard (eds.). 2017. The Routledge handbook of disaster risk reduction including climate change adaptation. Abingdon, U.K.: Routledge.

Kennedy, J., J. Ashmore, E. Babister, and I. Kelman. 2008. The meaning of ‘Build Back Better’: Evidence from post-tsunami Aceh and Sri Lanka. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 16(1): 24–36.

Kreis, I.A., A. Busby, G. Leonardi, J. Meara, and V. Murray (eds.). 2013. Essentials of environmental epidemiology for health protection: A handbook for field professionals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Krüger, F., G. Bankoff, T. Cannon, and L. Schipper. 2015. Cultures and disasters: Understanding cultural framings in disaster risk reduction. Abingdon: Routledge.

Leroy, S.A.G. 2006. From natural hazard to environmental catastrophe: Past and present. Quaternary International 158(1): 4–12.

Lewis, J. 1979. The vulnerable state: An alternative view. In Disaster assistance: Appraisal, reform and new approaches, ed. L.H. Stephens, and S.J. Green, 104–129. New York: New York University Press.

Lewis, J. 1988. On the line: An open letter in response to ‘Confronting natural disasters, an international decade for natural hazard reduction’. Natural Hazards Observer 7(4): 4.

Lewis, J. 1999. Development in disaster-prone places: Studies of vulnerability. London: Intermediate Technology Publications.

Lewis, J. 2013. Some realities of resilience: A case study of Wittenberge. Disaster Prevention and Management 22(1): 48–62.

Lewis, J., and I. Kelman. 2012. The good, the bad and the ugly: Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) versus Disaster Risk Creation (DRC). PLoS Currents Disasters. https://doi.org/10.1371/4f8d4eaec6af8.

Mika, K. 2019. Disasters, vulnerability, and narratives: Writing Haiti’s futures. Abingdon: Routledge.

O’Keefe, P., K. Westgate, and B. Wisner. 1976. Taking the naturalness out of natural disasters. Nature 260: 566–567.

Oliver-Smith, T. 1979. Post disaster consensus and conflict in a traditional society: The 1970 avalanche of Yungay, Peru. Mass Emergencies 4: 39–52.

Oliver-Smith, T. 2016. Disaster risk reduction and applied anthropology. Annals of Anthropological Practice 40(1): 73–85.

Peduzzi, P., H. Dao, C. Herold, and F. Mouton. 2009. Assessing global exposure and vulnerability towards natural hazards: The Disaster Risk Index. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 9(4): 1149–1159.

Perry, R., and E.L. Quarantelli. 2005. What is a disaster? New York: Xlibris.

Quarantelli, E.L. 1985. What is disaster? The need for clarification in definition and conceptualization. In Disasters and mental health: Selected contemporary perspectives, ed. B. Sowder, 41–73. Rockville, Md.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health.

Quarantelli, E.L. 1998. What is a disaster? New York: Routledge.

Reams, B.D., and E.C. Surrency. 1982. Insuring the law library: Fire and disaster risk management. London: Glanville.

Schuller, M., and P. Morales (eds.). 2012. Tectonic shifts: Haiti since the earthquake. Sterling: Kumarian Press.

Shaw, R., A. Sharma, and Y. Takeuchi (eds.). 2009. Indigenous knowledge and disaster risk reduction: From practice to policy. Hauppauge: Nova Publishers.

Smith, K. 2013. Environmental hazards: Assessing risk and reducing disaster, 6th edn. London: Routledge.

Stiftel, B., and C. Mukhopadhyay. 2007. Thoughts on Anglo-American hegemony in planning scholarship: Do we read each other’s work? Town Planning Review 78(5): 545–572.

Sudmeier-Rieux, K.I. 2014. Resilience—An emerging paradigm of danger or of hope? Disaster Prevention and Management 23(1): 67–80.

Tarhan, C., C. Aydin, and V. Tecim. 2016. How can be disaster resilience built with using sustainable development? [sic] Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 216: 452–459.

Timmerman, P. 1981. Vulnerability, resilience and the collapse of society: A review of models and possible climatic applications. Toronto: Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Toronto.

Torry, W.I. 1979. Hazards, hazes and holes: A critique of the environment as hazard and general reflections on disaster research. The Canadian Geographer 23(4): 368–383

UNDHA (United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs). 1992. Internationally agreed glossary of basic terms related to disaster management. Geneva: UNDHA.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2004. Reducing disaster risk: A challenge for development. New York: UNDP.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2004. Living with risk: A global review of disaster reduction initiatives. Geneva: UNISDR.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2005. Hyogo framework for action 2005–2015: Building the resilience of nations and communities to disasters. Geneva: UNISDR.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2009. Terminology. Geneva: UNISDR.

UNISDR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction). 2015a. Proposed updated terminology on disaster risk reduction: A technical review. Geneva: UNISDR.

UNISDR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction). 2015b. Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. Geneva: UNISDR.

UNISDR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction). 2017. Terminology on disaster risk reduction. Geneva: UNISDR. https://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/terminology. Accessed 4 May 2018.

Vermeiren, J.C. 1993. Disaster risk reduction as a development strategy. Washington, DC: Organization of American States.

Warheit, G.J. 1976. A note on natural disasters and civil disturbances: Similarities and differences. Mass Emergencies 1: 131–137.

Whitehand, J.W.R. 2005. The problem of anglophone squint. Area 37(2): 228–230.

Wisner, B. 2017. “Build back better”? The challenge of Goma and beyond. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 26: 101–105.

Wisner, B., P. Blaikie, T. Cannon, and I. Davis. 2004. At risk: Natural hazards, people’s vulnerability and disasters, 2nd edn. London: Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kelman, I. Lost for Words Amongst Disaster Risk Science Vocabulary?. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 9, 281–291 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-018-0188-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-018-0188-3