Abstract

Osteoblastoma is an uncommon benign bone-forming tumor that accounts for fewer than 1% of all bone neoplasms. Its periosteal subtype, “periosteal osteoblastoma”, is extremely rare, and the rarity of this tumor makes it difficult to draw conclusions regarding its clinical and radiological features. We report herein a case of periosteal osteoblastoma of the distal femur of a 17-year-old woman. As far as we are aware, the MR appearance of this tumor has not been well described. Periosteal osteoblastoma usually manifests on MR images as a bone-surface lesion accompanied by characteristic marked edema in the surrounding soft tissue, reflecting inflammation, without intramedullary edema. This case and a review of the literature suggested the advantage of MR imaging for differentiating periosteal osteoblastoma from other bone-forming surface-type lesions. We should be aware of this uncommon neoplasm when we encounter surface-type bone tumors, particularly in young patients with complaint of persistent pain and typical MR appearance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoblastoma is an uncommon benign bone-forming tumor that accounts for fewer than 1% of all bone tumors [1]. Although osteoblastoma mainly affects the posterior elements of the vertebral column, it also affects the long tubular bones, accounting for one-third of cases [2, 3]. However, the vast majority of those arising from the long tubular bones are intramedullary or intracortical lesions, and periosteal involvement is extremely rare. Only 20 cases of periosteal osteoblastoma arising from the long tubular bones have been reported in the last 40 years [4–14]. The rarity of this tumor makes it difficult to draw conclusions regarding its clinical features and typical imaging findings. As far as we are aware, the magnetic resonance (MR) imaging findings of periosteal osteoblastoma have not been well described. Therefore, we report herein an extremely rare case of periosteal osteoblastoma of the distal femur and sought to define the characteristic features of this tumor by reviewing the literature, especially highlighting its MR appearance.

Case report

A 17-year-old woman presented at a local hospital with a 2-year history of intermittent pain of her right knee. She felt dull pain that was worse at night and, initially, disappeared when she took non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. She had no past history of trauma. On physical examination, a firm, nonmovable mass was palpable at the medial side of her right knee and there was exquisite pain on pressure. There was no right knee effusion. The range of motion was between 0° and 120°, which, because of the pain, was restricted in flexion by 20° compared with the contralateral knee. All routine laboratory tests were within normal limits.

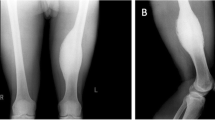

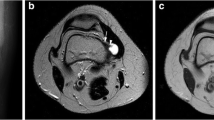

Plain radiographs revealed a small mineralized mass on the medial aspect of the distal femoral metaphysis with peripheral sclerosis and central lucency (Fig. 1). Computed tomography (CT) revealed a mineralized mass arising on the cortical surface projecting into the soft tissues. Slight thickening of the adjacent cortex was present. No cortical destruction or medullary involvement was noted (Fig. 2). MR imaging showed the well-demarcated lesion lying over the surface of the cortical bone, measuring approximately 1 cm. The lesion was isointense relative to skeletal muscle on T1-weighted images (Fig. 3a), hyperintense and heterogeneous on T2-weighted images (Fig. 3b), and moderately enhanced after intravenous administration of contrast medium (gadolinium diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid; Gd-DTPA). Extensive surrounding soft tissue edema seemed to reflect inflammatory change (Fig. 3b).

a Coronal T1-weighted MR image reveals a bone surface lesion that is homogeneous and isointense relative to skeletal muscle (Arrow). b Axial T2-weighted STIR image reveals a lesion that is heterogeneous and hyperintense (Arrow). Perilesional edema is apparent in the surrounding soft tissues (Arrow head). Intramedullary edema is not evident

From both the indolent clinical course and radiological findings, the preoperative differential diagnosis included benign tumors or tumor-like lesions originating from the surface of cortical bone, for example periosteal chondroma, fractured osteochondroma, periosteal osteoblastoma, myositis ossificans, florid reactive periostitis, bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation, avulsive cortical irregularity syndrome, or Pellegrini–Stieda disease. Because of continuous and uncontrollable pain despite the medication with analgesics, surgical excision was subsequently performed. Histologic examination of the resected specimen revealed the tumor was mainly composed of irregular trabeculae of osteoid, rimmed by mature-looking active osteoblasts with little polymorphism. The stroma was rather loose, with many capillaries and small spindle-shaped cells. Osteoclasts were scattered in the stroma and at the surface of the trabeculae (Fig. 4). On the basis of the clinical, radiological and histological findings, we diagnosed the lesion as periosteal osteoblastoma. Preoperative symptoms immediately disappeared after surgery and the patient’s postoperative course was uneventful. Her postoperative range of motion at the knee joint became normal. Sixteen months after the surgery, she was asymptomatic and no local recurrence was evident. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her family.

The tumor is mainly composed of irregular trabeculae of osteoid rimmed by mature-looking active osteoblasts with little polymorphism (H&E ×40). The stroma was rather loose, with many capillaries and small spindle-shaped cells. Osteoclasts were scattered in the stroma and at the surface of the trabeculae (inset ×400)

Discussion

Osteoblastoma is an uncommon benign bone tumor that was first described by Lichtenstein and Jaffe in 1956 [8]. It accounts for approximately 1% of all primary bone tumors and usually affects young adults before the age of 30 years [9]. Osteoblastoma frequently affects the posterior elements of vertebral column followed by the femur, mandible, tibia, and fibula [1]. These are usually forms of intramedullary or, occasionally, intracortical lesions and periosteal involvement is extremely rare [13]. Lichtenstein and Sawyer [8] first described the periosteal subtype of osteoblastoma in 1964 and only 33 cases (including our case) have been reported in the English literature (Table 1) [4–22].

Osteoblastoma usually occurs in the second and third decades of life, with cases reported from 6 months to 75 years of age [2, 3]. Osteoblastoma occurs most often in males (male to female ratio 2:1) [1, 18]. Most patients with osteoblastoma present with pain and/or tenderness and occasionally with swelling [2, 3, 23]. The duration of pain ranges from a few months to several years and the pain from osteoblastoma may become severe at night and may not respond to aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [23, 24]. As mentioned above, osteoblastoma occurs most often in the posterior elements of vertebral column and the diaphysis or metaphysis of long tubular bones of the appendicular skeleton (32% in the vertebral column, 12% in the femur, and 10% in the tibia) [2].

The 33 previously reported cases of periosteal osteoblastoma are summarized, with their demographics, in Table 1. Periosteal osteoblastoma has male preponderance, with male to female ratio, 18:7 [4–22]. The mean age of reported cases was 25 (range from 7 to 66) years [4–22]. The most frequent sites of involvement were the femur in 10, followed by the craniofacial bones in 8, the humerus in 4, the tibia and the rib in 3, the fibula in 2 [4–22]. It affects long tubular bone more frequently (20/32, 64%) than vertebral bone unlike the conventional type of osteoblastoma. When the tumors occur in the long tubular bones, the metaphysis and the diaphysis are most often involved [4–22]. The most common first manifestation was pain and/or swellings. Unlike our case, severe night pain, which is typical of osteoid osteoma, is not common for periosteal osteoblastoma or conventional osteoblastoma.

There have been several reports of radiographic findings for periosteal osteoblastoma. These typically reveal mildly increased soft tissue density and intralesional mineralization close to the cortex of the diaphysis or metaphysis of a long tubular bone [11]. Cortical erosion (with or without cortical thickening) and periosteal reactive bone formation can be seen [6, 11], however, cortical destruction with extensive invasion of the intramedullary space is unusual. The radiographic findings in our case are almost consistent with previous reports.

Periosteal osteoblastoma should be differentiated radiologically from other bone surface lesions including both benign and malignant processes. Such benign lesions include osteochondroma, periosteal chondroma, periosteal osteoblastoma, myositis ossificans, florid reactive periostitis, bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation, and avulsive cortical irregularity syndrome. In our case, Pellegrini–Stieda disease, known as ossification around the medial femoral condyle, was included in the differential diagnosis because of the site of the tumor. Malignant lesions include periosteal osteosarcoma, parosteal osteosarcoma, and high-grade surface osteosarcoma. Differentiating periosteal osteoblastoma from such malignant tumors is quite critical, because the treatment approach is different. In our case we evaluated the lesion as benign on the basis of the indolent course; in retrospect, however, it is thought to be difficult to diagnose this lesion as periosteal osteoblastoma from the clinical findings and the radiographic features only. The diagnostic difficulty may be attributed to the relatively non-specific radiographic findings and its extremely rare incidence.

MR findings of periosteal osteoblastoma have been reported in 4 cases only, and little information is available regarding its characteristic features [6, 7, 11, 13]. The MR findings obtained from previous reports are summarized in Table 2. Periosteal osteoblastoma was typically isointense relative to skeletal muscle on T1-weighted images, with a mixture of low and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Low signal intensity on T2-weighted images corresponded to mineralization. After administration of contrast medium, moderate enhancement was observed. Signal characteristics and enhancement patterns were non-specific. In 2 cases, focal areas with low signal intensity in the medullary cavity on T1-weighted images were noted adjacent to the tumor [6, 11]. This finding was not present in our case. In 4 cases, characteristic marked perilesional edema, reflecting inflammation, was noted not in the medullary cavity but only in the surrounding soft tissues. The characteristic MR appearances mentioned above, i.e., surrounding soft tissue edema without intramedullary edema, would be helpful in preoperative differential diagnosis.

In summary, this report emphasizes the need for periosteal osteoblastoma to be included in the differential diagnosis of any bone-surface lesions arising from the metaphysis or the diaphysis of long bones of young adults, particularly when characteristic surrounding soft tissue edema without intramedullary edema on T2-weighted STIR images. Although it is unlikely that such a rare condition could reasonably diagnosed on the basis of MR findings alone, recognizing this extremely rare variant of osteoblastoma is nonetheless important for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.

References

Unni KK (1996) Dahlin’s bone tumors. In: General aspects and data on 11,087 cases, 5th edn. Lippincott Raven, Philadelphia

Lucas DR, Unni KK, McLeod RA et al (1994) Osteoblastoma: clinicopathologic study of 306 cases. Hum Pathol 25(2):117–134

Papagelopoulos PJ, Galanis EC, Sim FH et al (1999) Clinicopathologic features, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoblastoma. Orthopedics 22(2):244–247

Forest M, Tomeno B, Vanel D (1997) Orthopedic surgical pathology, 1st edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

Goldman RL (1971) The periosteal counterpart of benign osteoblastoma. Am J Clin Pathol 56(1):73–78

Kawaguchi K, Oda Y, Miura H et al (1998) Periosteal osteoblastoma of the distal humerus. J Orthop Sci 3(6):341–345

Kaya A, Altay T, Sezak M et al (2009) Periosteal osteoblastoma of the distal femur. Acta Orthop Belg 75(2):280–285

Lichtenstein L, Sawyer WR (1964) Benign osteoblastoma. Further observations and report of twenty additional cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 46:755–765

Mirra JM, Picci P, Gold RH (1989) Bone tumors. In: Clinical, radiological and pathologic correlation, 1st edn. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia

Mortazavi SM, Wenger D, Asadollahi S et al (2007) Periosteal osteoblastoma: report of a case with a rare histopathologic presentation and review of the literature. Skelet Radiol 36(3):259–264

Nakatani T, Yamamoto T, Akisue T et al (2004) Periosteal osteoblastoma of the distal femur. Skelet Radiol 33(2):107–111

Schajowicz F (1994) Bone-forming tumors. In: Schajowicz F (ed) Tumors and tumor-like lesions of bone, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin, pp 29–140

Sulzbacher I, Puig S, Trieb K et al (2000) Periosteal osteoblastoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Pathol Int 50(8):667–671

Tonai M, Campbell CJ, Ahn GH et al (1982) Osteoblastoma: classification and report of 16 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 167:222–235

Chatterji P, Purohit GN, Ramdeo Bikaner IN (1978) Benign osteoblastoma of the maxilla (periosteal). J Laryngol Otol 92(4):337–345

Farman AG, Nortje CJ, Grotepass F (1976) Periosteal benign osteoblastoma of the mandible. Report of a case and review of the literature pertaining to benign osteoblastic neoplasms of the jaws. Br J Oral Surg 14(1):12–22

Gentry JF, Schechter JJ, Mirra JM (1989) Case report 574. Periosteal osteoblastoma of rib. Skelet Radiol 18(7):551–555

Huvos AG (1991) Osteoblastoma. In: Huvos AG (ed) Bone tumors: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. 2nd edn. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 67–83

Lee EJ, Park CS, Song SY et al (2004) Osteoblastoma arising from the ethmoidal sinus. AJR Am J Roentgenol 182(5):1343–1344

Lin YC, Commins DL, Fedenko AN et al (2005) A rare case of periosteal osteoblastoma located in the frontal cranial bone. Arch Pathol Lab Med 129(6):787–789

Stephens L, Devaney D, Stephens M (2007) Periosteal osteoblastoma. Ir Med J 100(6):506

Tawil A, Comair Y, Nasser H et al (2008) Periosteal osteoblastoma of the calvaria mimicking a meningioma. Pathol Res Pract 204(6):413–422

Arkader A, Dormans JP (2008) Osteoblastoma in the skeletally immature. J Pediatr Orthop 28(5):555–560

Berry M, Mankin H, Gebhardt M et al (2008) Osteoblastoma: a 30-year study of 99 cases. J Surg Oncol 98(3):179–183

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Ogura, K., Ushiku, T., Shinoda, Y. et al. Periosteal osteoblastoma of the distal femur: a case report and a review of the literature with special emphasis on the MR features. Int Canc Conf J 1, 103–107 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13691-012-0020-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13691-012-0020-7