Abstract

In clinical trials, conclusions on treatment safety and efficacy depend on the selected outcomes; therefore, it is very important to choose outcomes that are able to address meaningful aspects of the disease experience. This review analyzes 54 clinical trials of psoriasis treatments that took place from January 2011 to March 2012. The majority of the primary outcomes were based exclusively on the clinician/investigator assessment. Twenty-four percent of studies had a patient-reported measure listed as primary outcome. However, of the 34 studies reporting secondary outcomes, only seven had secondary outcomes based exclusively on the clinician/investigator assessment. Although there is a trend toward an increase in trials incorporating patient-reported measures, it is necessary to improve the quality of the measures used, and to adopt more thoroughly validated and homogeneous clinical measures and times of follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The choice of outcomes in clinical trials is crucial. The results of a trial indicate the use of a treatment, as well as its safety and its efficacy. It is, thus, essential to choose the right outcomes to take into account what really matters in health care—patients’ health and well-being. However, guidelines indicating what should be measured in clinical trials are lacking. An example of systematization of measures in clinical trials is Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials (OMERACT), a network aimed at defining a common set of measures in rheumatology, which would allow comparison between trials and use in meta-analyses [1]. Such a network has not been created yet for psoriasis, and a plethora of outcomes are used in clinical trials of this disease.

Psoriasis is a disease with a strong involvement of psychosocial aspects. It is well-known that severity measures alone are not able to thoroughly depict the burden of psoriasis on patients [2••], since the same severity level may have a different impact on health-related quality of life. Concerning outcomes, something has changed over the last 20 years. Morsy et al. [3] compared outcomes in clinical trials of psoriasis from 2004 to 2005 with those analyzed by Marks et al. [4] in 1989 and observed that the main difference was the introduction of quality of life measures. However, a lack of standardization for all kinds of measures was reported. Even for the assessment of psoriasis severity—traditionally scored by the clinician on the basis of area involved, erythema, scaling, and induration—there was no homogeneity. Naldi et al. [5] found that in 171 randomized controlled trials of psoriasis from 1977 to 2000, 44 different scoring systems were used. The aim of this review is to analyze in detail the outcomes of clinical trials of psoriasis published between January 2011 and March 2012.

Methods

We performed a search for clinical trials in psoriasis using the PubMed MeSH database. We used the keyword psoriasis, the search limits type of study “phase III clinical trial,” and time period from January 1, 2011, to March 31, 2012. The search identified 123 articles. Of those articles, we selected 60 articles that directly dealt with the structured evaluation of psoriasis treatments. Of these articles, three did not concern the efficacy of treatment and one was in Chinese, one focused on arthritis and included only six out 60 patients with psoriatic arthritis, and one was a commentary on a trial. Thus, we analyzed outcomes in 54 clinical trials.

Each article was read by both authors and, when not explicitly stated, a consensus was reached about what was considered as primary outcome. For example, when the methods did not indicate the primary outcome, we referred to the results section and to the tables and figures to see which variable(s) was (were) used in the analysis. The same process applied to the secondary outcomes. We did not extract information about the variables indicated as “exploratory outcomes.” Other information that we extracted from each paper included the main interventions, the reported sample size, the presence of a reported power calculation, and the presence and the type of masking.

Table 1 provides a summary of the interventions and outcomes in the 54 studies we reviewed. We organized the studies according to the different clinical types of psoriasis: plaque, arthropathica, palmoplantar, and scalp. One study reported on chronic plaque psoriasis of the hands and feet only, so we listed it separately. As for the interventions, we included in Table 1 only information about the type of treatment, not about the doses; however, we indicated the number of different dose/treatment regimens.

Results

The characteristics of the 54 studies selected at the end of the search and screening process are summarized in Table 1, and listed in alphabetical order by the first author for each clinical type of psoriasis. Forty-three studies were conducted on patients with plaque psoriasis, five of patients with psoriatic arthritis, three of patients with palmoplantar psoriasis, two of patients with scalp psoriasis, and one of patients with plaque psoriasis of hands and feet. Seventeen studies included a description of the power analysis/sample size calculation, whereas the others either were the continuation of previous trials (and thus based on variable principles of efficacy or inefficacy) or did not motivate the choice of the sample size. Of the studies, 25 were double-blind (one of these was quadruple-blind), seven were single-blind, and 22 were open-label or had no mention of patient or investigator blinding. Of the 16 studies with the power calculation, 11 were double-blind and two were single-blind.

Primary Outcomes

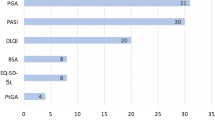

Of the 54 selected studies, 41 had a primary outcome based exclusively on the clinician/investigator assessment. The most used measures were the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) (usually PASI 75 but also Δ PASI) and the Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) (mainly with a target score of 0 or 1 corresponding to “clear” or “almost clear”). The combination of these measures—including their various modifications (eg, Psoriasis Severity Index [PSI], which excludes the area from the PASI calculation; Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis Area and Severity Index [PPPASI]) or variations in which different names are applied to the same instrument (eg, overall disease severity [ODS]; Investigator’s Global Assessment [IGA])—covers 49 of the 54 studies. One study without these clinical severity measures evaluated a treatment with narrowband UVB and used the number of treatments to clearance and/or minimal residual activity (MRA) as primary outcome.

The four studies using only patient-reported outcomes are secondary reports. Two focused on work productivity, using specific measures such as the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Specific Health Problem (WPAI-SHP) and the Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ). The other two focused on quality of life, using Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Psoriasis Disability Index (PDI), and Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ). In addition, nine studies listed patient-reported measures among their primary outcomes. Three more studies used the DLQI and another the HAQ; quality of life was also measured using the EuroQol (EQ-5D), the Skindex-16, and the Physical Functioning (PF) scale of the Medical Outcomes Study short form (SF-36). The remaining patient-reported primary outcomes included the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for itch, pain, and well-being; the Patient Global Assessment (PtGA); and the patient’s overall assessment of treatment response. Each of these measures were listed in only one study.

Secondary Outcomes

Twenty studies did not report any secondary outcome. Although this may reflect publication bias (eg, because of word-count restrictions), it still amounts to approximately 40 % of the studies considered. Ideally, an optimal analysis of such studies would include a review of the study protocols. Of the remaining 34, only seven had secondary outcomes based exclusively on the clinician/investigator assessment. Twenty-four studies listed the PASI in several of its possible forms (eg, PSI, m-PASI) and at the conventional cutoff points (eg, PASI 50, -90, -100). In addition, these PASI measures were often considered at different times and for a number of studies even at every follow-up visit. The PGA was listed in 16 studies and, as described for the PASI, different cutoff points and observation times were often used.

Of the 27 studies listing at least a patient-reported measure as secondary outcome, four had only patient-reported outcomes: one had the VAS for itch, one the HLQ for work productivity, one a mixture of quality of life and work productivity instruments, and one quality of life questionnaires and a willingness to pay assessment. Among the studies with a patient-reported outcome, 14 listed the generic dermatologic DLQI and only two the psoriasis-specific PDI. The SF-36, a questionnaire used to describe general health status, was used in five studies. The PtGA among the secondary outcomes was listed five times.

Discussion

This review analyzes the outcomes of 54 psoriasis trials published between January 2011 and March 2012. We observed that the majority of the studies had a primary outcome based exclusively on the clinician/investigator assessment. The PASI, although expressed in many different forms (eg, proportion of patients reaching PASI 75, absolute or percent change in PASI score), is still the most used measure to evaluate clinical severity of psoriasis, even though it has never been standardized or its reliability demonstrated. As Naldi suggested [6], PASI should be considered passé, and better clinimetrics of disease severity should be developed. This lack of validity and inability to catch important symptoms arising from psoriasis [7] seem to support Naldi’s view.

However, the PASI score is widely used in clinical trials, and a valid alternative has not been suggested. Reasons for its widespread use may include its apparent “objective” nature, which some may perceive as comparable and interpretable. In addition, other measures of clinical severity (eg, the PGA, IGA, PSI) have been even less rigorously examined than PASI. Comparability of PASI is most likely a myth, not only because of a lack of standardized comparative studies across institutions and countries but because of the vast diversity of times at which it is assessed as an outcome. In this review, even when only considering the primary outcomes, the change in PASI score was assessed in the different studies at weeks 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 20, 25, 52, and 160. In addition, one study used it at 35 sessions of phototherapy. Taken together this adds up to 12 different criteria of evaluation of an apparently single measure and clearly limits comparability across studies, even though the same measure of clinical severity was used.

The other commonly used measure for clinical outcome was PGA. PGA is a very simple measure to use both in clinical trials and in clinical practice, and it provides an overall score indicating the degree of severity on a scale, generally from 1 to 5. It does not include the details of PASI (ie, area, erythema, desquamation, and induration); however, the final result of PASI is also a single score. No studies detail whether PASI and PGA are evaluated by the same person; however, it seems likely that the same person does both and that PGA is likely to be “driven” by PASI. In fact, in a study analysing 30 clinical trials for biologics in psoriasis, Robinson et al. [8•] showed that the correlation between PASI 75 and a score of clear or almost clear on the PGA were 0.916 at 8 to 16 weeks and 0.892 at 17 to 24 weeks. The high correlation, according to the authors, indicated that the two assessment tools are redundant and one might be enough to assess psoriasis severity.

Although the correlation between these two physician-reported measures is extremely high, we have recently observed [9] that the agreement between PGA and the equivalent patient-assessed measure, PtGA, is scarce. On a sample of over 2500 dermatologic outpatients, the overall Cohen’s κ between the two clinical severity evaluations was very low (k = 0.25), possibly further illustrating the lack of standardization and validity of PGA.

In general, the correlation between physician- and patient-reported measures in psoriasis has been shown to be low [2••]. This should be of concern because these two classes of assessments seem to measure different constructs, so what may be considered a treatment “success” by a physician may be a disappointing outcome for the patient. Despite this, in the 54 clinical trials analyzed in this review, only about one fourth included a patient-reported measure among the primary outcomes. These figures are quite similar to those of Townshend et al. [10], who, in 2003, analyzed 125 dermatologic trials and found that only 32 of them (25.6 %) mentioned participant efficacy outcomes. Another study observed that, even when information on quality of life was available [11], methods and results were not adequately reported. Of note, in our review, we observed that no power calculation was based on a patient-reported outcome.

When looking at quality of life assessment, it is somewhat surprising to observe the clear preference for generic dermatologic rather than psoriasis-specific instruments. In fact, the DLQI is listed four times as a primary outcome and 14 times as a secondary outcome, whereas the PDI is listed once among the primary and twice among the secondary outcomes. No other psoriasis-specific questionnaires are mentioned, whereas several generic nondermatologic questionnaires are reported (eg, SF-36, HAQ, EQ-5D). In no instance, the recommendations contained in an in-depth critical review of generic and dermatology-specific quality of life instruments [12••] were followed. In fact, not only was the combination of SF-36 and Skindex-29 unobserved, but the SF-36 was included only once among the primary outcomes and five times among the secondary outcomes while the Skindex-29 went unmentioned in either the primary or secondary outcomes.

Surprisingly, when considering other patient-reported outcomes, we found a very rare occurrence of PtGA. Although PtGA obviously shares the convenience of PGA, in this review it was found in only one of 54 studies as a primary outcome and in five of the 34 studies listing at least a secondary outcome. In addition, an important measure such as the patient’s overall assessment of treatment response appeared in only one study as a primary outcome. Among these other outcomes, we found that different indexes of work productivity were used in the evaluation of treatment efficacy—in two studies as a primary outcome and in two other studies as a secondary outcome.

As for the clinical types other than plaque psoriasis, we saw that several indexes of clinical severity in addition to PASI and PGA or their modifications were used. Such indexes included, for example, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response criteria, the 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28), the psoriatic arthritis MRI scoring system (PAMRIS), the total sign score (TSS) for scalp involvement, and the Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI). On the other hand, no specific patient-reported severity or quality of life tools such as the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE), the Scalpdex for scalp psoriasis, or the nail psoriasis quality of life scale (NPQ10) were used.

The risk of relapse/rebound during or after treatment, an important aspect of the clinical course of psoriasis, was also scarcely evaluated. Not only were follow-up times usually too short, as shown in Table 1, to measure such occurrence, but only two trials [13•, 14•] explicitly listed relapse/rebound among their primary or secondary outcomes. However, as noted previously, this may also be because of publication bias, and an analysis of the study protocols could add a useful insight in this important aspect of treatment efficacy evaluation in psoriasis.

Conclusion

Compared to previous reports, we observed an increase in patient-reported outcomes in psoriasis clinical trials. A promising trend had already been reported in 2010 [15••], when the proportion of trials incorporating a quality of life measure was 7.7 % compared to 0.4 % in 2003. Here the proportion of studies with a quality of life measure listed as primary outcome was 11 %, and such proportion was 24 % when other patient-reported measures such as PtGA or WPAI-SHP were considered.

However, we recommend that the increase in trials incorporating patient-reported measures be combined with an increase in the quality of the measures used [12••]. Also, regulatory agencies, trial registers, and medical journals should require investigators to adopt more thoroughly validated and more standardized clinical measures and times of follow-up.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Tugwell P, Boers M, Brooks P, et al. OMERACT: an international initiative to improve outcome measurement in rheumatology. Trials. 2007;8:38.

•• Sampogna F, Sera F, Abeni D. Measures of clinical severity, quality of life, and psychological distress in patients with psoriasis: a cluster analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122(3):602–7. This paper demonstrates that measures of clinical severity in psoriasis have a very scarce correlation with patient-reported measures, indicating that one class of measures cannot be used as a substitute for the other.

Morsy H, Kamp S, Jemec GB. Outcomes in randomized controlled trials in psoriasis: what has changed over the last 20 years? J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18(5):261–7.

Marks R, Barton SP, Shuttleworth D, Finlay AY. Assessment of disease progress in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125(2):235–40.

Naldi L, Svensson A, Diepgen T, et al. Randomized clinical trials for psoriasis 1977–2000: the EDEN survey. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120(5):738–41.

Naldi L. Scoring and monitoring the severity of psoriasis. What is the preferred method? What is the ideal method? Is PASI passe? Facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28(1):67–72.

Sampogna F, Gisondi P, Melchi CF, et al. Prevalence of symptoms experienced by patients with different clinical types of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(3):594–9.

• Robinson A, Kardos M, Kimball AB. Physician Global Assessment (PGA) and Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI): why do both? A systematic analysis of randomized controlled trials of biologic agents for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(3):369–75. This study shows an exceedingly high correlation between PASI and PGA, indicating that measures can be used as a substitute for the each other.

Tabolli S, Sampogna F, Pagliarello C, et al. Disease severity evaluation among dermatological out-patients: a comparison between the assessments of patients and physicians. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(2):213–8.

Townshend AP, Chen CM, Williams HC. How prominent are patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials of dermatological treatments? Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(5):1152–9.

Le Cleach L, Chassany O, Levy A, et al. Poor reporting of quality of life outcomes in dermatology randomized controlled clinical trials. Dermatology. 2008;216(1):46–55.

•• Both H, Essink-Bot ML, Busschbach J, Nijsten T. Critical review of generic and dermatology-specific health-related quality of life instruments. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(12):2726–39. This in-depth analysis focuses on the parameters that contribute to the validity of quality of life questionnaires in dermatology and provides recommendations for their use.

• Kimball AB, Gordon KB, Langley RG, et al. Efficacy and safety of ABT-874, a monoclonal anti-interleukin 12/23 antibody, for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: 36-week observation/retreatment and 60-week open-label extension phases of a randomized phase II trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(2):263–74. This is one of the rare studies to address the important issue of loss of efficacy of treatment, using median time to loss of PASI 75 as a primary outcome.

• Naldi L, Yawalkar N, Kaszuba A, et al. Efficacy and safety of the Betamethasone valerate 0.1% plaster in mild-to-moderate chronic plaque psoriasis: a randomized, parallel-group, active-controlled, phase III study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12(3):191–201. This is the only trial, among those selected here, that considers the relapse/rebound of psoriasis as an outcome.

•• Naldi L, Svensson A, Zenoni D, et al. Comparators, study duration, outcome measures and sponsorship in therapeutic trials of psoriasis: update of the EDEN Psoriasis Survey 2001–2006. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(2):384–9. This is a comprehensive review of clinical trials in psoriasis that takes a rigorous, evidence-based medicine point of view.

Abdallah MA, El-Khateeb EA, Abdel-Rahman SH. The influence of psoriatic plaques pretreatment with crude coal tar vs. petrolatum on the efficacy of narrow-band ultraviolet B: a half-vs.-half intra-individual double-blinded comparative study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27(5):226–30.

Bagel J. Adalimumab plus narrowband ultraviolet B light phototherapy for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(4):366–71.

Barker J, Hoffmann M, Wozel G, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab vs. methotrexate in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of an open-label, active-controlled, randomized trial (RESTORE1). Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(5):1109–17.

Calzavara-Pinton P, Rossi MT, Sala R, Venturini M. The separate daily application of tacalcitol 4 microg/g ointment and budesonide 0.25 mg/g cream is more effective than the single daily application of a two compound ointment containing calcipotriol 50 microg/g and betamethasone dipropionate 0.5 mg/g. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2011;146(4):295–9.

Chauhan PS, Kaur I, Dogra S, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B versus psoralen plus ultraviolet A therapy for severe plaque psoriasis: an Indian perspective. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36(2):169–73.

Dawe RS, Cameron HM, Yule S, et al. A randomized comparison of methods of selecting narrowband UV-B starting dose to treat chronic psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(2):168–74.

Ehsani AH, Ghaninejad H, Kiani A, et al. Comparison of topical 8-methoxypsoralen and narrowband ultraviolet B with narrowband ultraviolet B alone in treatment-resistant sites in plaque-type psoriasis: a placebo-controlled study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27(6):294–6.

el-Mofty M, el-Darouti M, Rasheed H, et al. Sulfasalazine and pentoxifylline in psoriasis: a possible safe alternative. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22(1):31–7.

Faghihi T, Radfar M, Mehrabian Z, et al. Atorvastatin for the treatment of plaque-type psoriasis. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31(11):1045–50.

Fallah Arani S, Neumann H, Hop WC, Thio HB. Fumarates vs. methotrexate in moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a multicentre prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(4):855–61.

Gambichler T, Tigges C, Scola N, et al. Etanercept plus narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy of psoriasis is more effective than etanercept monotherapy at 6 weeks. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(6):1383–6.

Gordon K, Papp K, Poulin Y, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis treated continuously over 3 years: results from an open-label extension study for patients from REVEAL. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(2):241–51.

Gordon KB, Langley RG, Gottlieb AB, et al. A phase III, randomized, controlled trial of the fully human IL-12/23 mAb briakinumab in moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(2):304–14.

Gottlieb AB, Leonardi C, Kerdel F, et al. Efficacy and safety of briakinumab vs. etanercept and placebo in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(3):652–60.

Hudson CP, Kempers S, Menter A, et al. An open-label, multicenter study of the efficacy and safety of a weekday/weekend treatment regimen with calcitriol ointment 3 microg/g and clobetasol propionate spray 0.05 % in the management of plaque psoriasis. Cutis. 2011;88(4):201–7.

Kimball AB, Bensimon AG, Guerin A, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab among patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with co-morbidities: Subanalysis of results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12(1):51–62.

Kimball AB, Yu AP, Signorovitch J, et al. The effects of adalimumab treatment and psoriasis severity on self-reported work productivity and activity impairment for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(2):e67–76.

Kircik LH. Topical calcipotriene 0.005 % and betamethasone dipropionate 0.064 % maintains efficacy of etanercept after step-down dose in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of an open label trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(8):878–82.

Klein A, Schiffner R, Schiffner-Rohe J, et al. A randomized clinical trial in psoriasis: synchronous balneophototherapy with bathing in Dead Sea salt solution plus narrowband UVB vs. narrowband UVB alone (TOMESA-study group). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(5):570–8.

Kunynetz R, Carey W, Thomas R, et al. Quality of life in plaque psoriasis patients treated with voclosporin: a Canadian phase III, randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21(1):89–94.

Langley RG, Gupta A, Papp K, et al. Calcipotriol plus betamethasone dipropionate gel compared with tacalcitol ointment and the gel vehicle alone in patients with psoriasis vulgaris: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Dermatology. 2011;222(2):148–56.

Leonardi C, Matheson R, Zachariae C, et al. Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(13):1190–9.

Morken T, Bohov P, Skorve J, et al. Anti-inflammatory and hypolipidemic effects of the modified fatty acid tetradecylthioacetic acid in psoriasis–a pilot study. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2011;71(4):269–73.

Mortazavi H, Khezri S, Hosseini H, et al. A single blind randomized clinical study: the efficacy of isotretinoin plus narrow band ultraviolet B in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27(3):159–61.

Ortonne JP, Chimenti S, Reich K, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with psoriasis previously treated with anti-tumour necrosis factor agents: subanalysis of BELIEVE. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(9):1012–20.

Pacifico A, Leone G. Evaluation of a skin protection cream for dry skin in patients undergoing narrow band UVB phototherapy for psoriasis vulgaris. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2011;146(3):179–83.

Papp KA, Leonardi C, Menter A, et al. Brodalumab, an anti-interleukin-17-receptor antibody for psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(13):1181–9.

Papp KA, Poulin Y, Bissonnette R, et al. Assessment of the long-term safety and effectiveness of etanercept for the treatment of psoriasis in an adult population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(2):e33–45.

Patel T, Bhutani T, Busse KL, Koo J. Evaluating the efficacy and safety of calcipotriene/betamethasone ointment occluded with a hydrogel patch: a 6-week bilaterally controlled, investigator-blinded trial. Cutis. 2011;88(3):149–54.

Prinz JC, Fitzgerald O, Boggs RI, et al. Combination of skin, joint and quality of life outcomes with etanercept in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the PRESTA trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(5):559–64.

Radmanesh M, Rafiei B, Moosavi ZB, Sina N. Weekly vs. daily administration of oral methotrexate (MTX) for generalized plaque psoriasis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50(10):1291–3.

Reich K, Langley RG, Papp KA, et al. A 52-week trial comparing briakinumab with methotrexate in patients with psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(17):1586–96.

Reich K, Schenkel B, Zhao N, et al. Ustekinumab decreases work limitations, improves work productivity, and reduces work days missed in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from PHOENIX 2. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22(6):337–47.

Saurat JH, Langley RG, Reich K, et al. Relationship between methotrexate dosing and clinical response in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: subanalysis of the CHAMPION study. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(2):399–406.

Shintani Y, Kaneko N, Furuhashi T, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed-dose cyclosporin microemulsion (100 mg) for the treatment of psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2011;38(10):966–72.

Strober BE, Crowley JJ, Yamauchi PS, et al. Efficacy and safety results from a phase III, randomized controlled trial comparing the safety and efficacy of briakinumab with etanercept and placebo in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(3):661–8.

Strober BE, Poulin Y, Kerdel FA, et al. Switching to adalimumab for psoriasis patients with a suboptimal response to etanercept, methotrexate, or phototherapy: efficacy and safety results from an open-label study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4):671–81.

Tsai TF, Ho JC, Song M, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in Taiwanese and Korean patients (PEARL). J Dermatol Sci. 2011;63(3):154–63.

Weinstabl A, Hoff-Lesch S, Merk HF, von Felbert V. Prospective randomized study on the efficacy of blue light in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatology. 2011;223(3):251–9.

Wolf P, Weger W, Legat FJ, et al. Treatment with 311-nm ultraviolet B enhanced response of psoriatic lesions in ustekinumab-treated patients: a randomized intraindividual trial. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(1):147–53.

Yan H, Tang M, You Y, et al. Treatment of psoriasis with recombinant human LFA3-antibody fusion protein: a multi-center, randomized, double-blind trial in a Chinese population. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21(5):737–43.

Atzeni F, Boccassini L, Antivalle M, et al. Etanercept plus ciclosporin versus etanercept plus methotrexate for maintaining clinical control over psoriatic arthritis: a randomised pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(4):712–4.

Gladman DD, Bombardier C, Thorne C, et al. Effectiveness and safety of etanercept in patients with psoriatic arthritis in a Canadian clinical practice setting: the REPArE trial. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(7):1355–62.

Karanikolas GN, Koukli EM, Katsalira A, et al. Adalimumab or cyclosporine as monotherapy and in combination in severe psoriatic arthritis: results from a prospective 12-month nonrandomized unblinded clinical trial. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(11):2466–74.

McQueen F, Lloyd R, Doyle A, et al. Zoledronic acid does not reduce MRI erosive progression in PsA but may suppress bone oedema: the Zoledronic Acid in Psoriatic Arthritis (ZAPA) Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):1091–4.

Mease P, Genovese MC, Gladstein G, et al. Abatacept in the treatment of patients with psoriatic arthritis: results of a six-month, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(4):939–48.

Bissonnette R, Poulin Y, Guenther L, et al. Treatment of palmoplantar psoriasis with infliximab: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(12):1402–8.

Furuhashi T, Torii K, Kato H, et al. Efficacy of excimer light therapy (308 nm) for palmoplantar pustulosis with the induction of circulating regulatory T cells. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20(9):768–70.

Khandpur S, Sharma VK. Comparison of clobetasol propionate cream plus coal tar vs. topical psoralen and solar ultraviolet A therapy in palmoplantar psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36(6):613–6.

Jemec GB, van de Kerkhof PC, Enevold A, Ganslandt C. Significant one week efficacy of a calcipotriol plus betamethasone dipropionate scalp formulation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(1):27–32.

Sofen H, Hudson CP, Cook-Bolden FE, et al. Clobetasol propionate 0.05 % spray for the management of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis of the scalp: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(8):885–92.

Leonardi C, Langley RG, Papp K, et al. Adalimumab for treatment of moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis of the hands and feet: efficacy and safety results from REACH, a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(4):429–36.

Disclosure

F. Sampogna: payment for lectures from Abbott and Janssen, payment for manuscript preparation from Abbott, and payment for development of educational presentations from Abbott; D. Abeni: consultant to Pfizer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sampogna, F., Abeni, D. Outcomes in Psoriasis Clinical Trials from January 2011 to March 2012. Curr Derm Rep 1, 137–147 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13671-012-0019-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13671-012-0019-5