Abstract

Management of women with a pelvic mass is a very common scenario for gynecologists. Often these are benign masses that can either be observed or managed with straightforward laparoscopic surgery, but complex, potentially malignant masses require careful consideration and triaging for appropriate care. This article aims to outline the presentation, management, and triage guidelines for women presenting with an ovarian cyst or pelvic mass. We discuss data surrounding the use of triage guidelines, as well as the role of promising biomarkers that can assist in better predicting benign versus malignant pathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Up to 300,000 women are hospitalized each year in the United States for evaluation of a pelvic mass, and the majority undergo surgery for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Most of these women have benign disease, but epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is diagnosed in up to 20% [1, 2]. Multiple studies have demonstrated that women with EOC have decreased morbidity and improved survival when their surgeries are performed by surgeons experienced in the management of EOC in specialized centers [3–7]. Therefore, it is crucial that management of pelvic masses by gynecologists includes not only evaluation of the differential diagnosis and appropriate operative interventions, but also emphasizes preoperative discrimination between benign and malignant masses so that appropriate referrals to gynecologic oncologists can be made. This review discusses the differential diagnosis of pelvic masses, available tools to assist gynecologists in assessing the risk of malignancy preoperatively, and special considerations when managing pelvic masses.

Differential Diagnoses

The differential diagnosis of a new pelvic mass is broad and depends upon the patient’s age. In premenopausal women, the most common adnexal finding is a functional or corpus luteal cyst, both of which typically resolve without intervention. However, the differential diagnosis also includes benign ovarian neoplasms, endometriomas, leiomyomata, tubo-ovarian abscesses, and ectopic pregnancies. Therefore, assessment for pregnancy and risk factors for sexually transmitted infections are an important part of the evaluation of pelvic masses in this age group. Malignancies are less common but must be considered. They include germ cell, sex-cord, or stromal tumors, in addition to the remote risk of EOC.

Among postmenopausal women, malignancy is more common, though the majority of women with pelvic masses have benign disease. In addition to the possibilities listed above, nongynecologic conditions such as diverticular abscesses and metastases from other primary cancers must be considered [8, 9]. Consideration for surgical intervention is based upon the patient’s symptoms and the risk of malignancy.

Tools for Distinguishing Benign From Malignant Masses

History and Physical Examination

Careful attention should be paid to addressing symptoms associated with ovarian cancer. The presentation is often vague, but Goff et al. [10] have established a list of symptoms commonly associated with the diagnosis of EOC, which typically are present for less than a year and more than 12 days a month. They are pelvic or abdominal pain, urinary urgency or frequency, increased abdominal size or bloating, and difficulty eating or early satiety [10].

When evaluating a woman with a pelvic mass, it is important to identify risk factors for malignancy. The most important risk factor for ovarian cancer is age, as rates increase rapidly after menopause and the median age of diagnosis is 63 years. Family history of breast or ovarian cancer also increases risk, but the degree of risk for women without an identified gene mutation is unknown. BRCA1 carriers have a 60-fold increased risk, whereas BRCA2 carriers have a 30-fold increased risk compared with the general population [11]. Women with mutations in the mismatch repair genes that cause the hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndrome (also known as Lynch syndrome) have a 13-fold risk of developing ovarian cancer compared with the general population [12]. Additional risk factors for EOC include nulliparity, primary infertility, and a history of endometriosis [13].

The physical examination is an important part of the evaluation of women with pelvic masses. As obesity becomes more common, however, the role of the physical exam becomes more limited. Even under anesthesia, physical examination is a poor predictor of the etiology of pelvic masses [14].

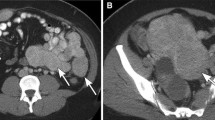

Imaging

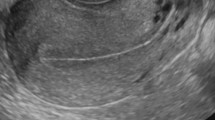

Pelvic ultrasound (US) is the modality most commonly used to evaluate pelvic anatomy in women, and the finding of a cystic pelvic mass is common. In October 2009, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound developed an evidence-based consensus statement defining recommendations for monitoring these findings if surgical intervention is not pursued [15•]. Simple cysts less than 10 cm in size are almost always benign. In premenopausal women, simple ovarian cysts measuring 5 cm or less do not need follow-up imaging. Simple cysts between 5 cm and 7 cm should be followed with yearly US, and those larger than 7 cm should have further imaging with MRI or surgical excision. In postmenopausal women, a simple cyst between 1 cm and 7 cm in size should be followed with yearly US, with the option to decrease frequency once stability or a decrease in size is documented. Cysts larger than 7 cm should be managed as in the premenopausal patient [15•].

Complex cysts are also benign most of the time. With improved technology and experience in imaging, these often can be characterized as a hemorrhagic cyst, endometrioma, or dermoid. Hemorrhagic cysts should resolve without intervention. If they are larger than 5 cm on US, the recommendation is to repeat ultrasound in 8 to 12 weeks to document resolution. Women in late menopause should not have hemorrhagic cysts, as they are a result of ovulation.

Endometriomas also appear as complex cysts and can be followed conservatively in young, asymptomatic women. Initially, short follow-up US is recommended to ensure that it is not confused with a hemorrhagic cyst. Otherwise, endometriomas managed conservatively should be followed at least yearly, with timing adjusted for age, size, and symptoms [15•]. Although about 1% of endometriomas can undergo malignant transformation, most associated malignancies occur in women older than 45 years with an endometrioma larger than 9 cm. Rapid growth or development of a solid component should raise concern [16].

For patients with the classic features of a dermoid, follow-up US every 6 to 12 months should be sufficient to ensure stability of size [15•]. Cysts with indeterminate features should be followed more closely than the guidelines outlined above, and masses with findings concerning for malignancy, including thick septations, solid elements with internal blood flow, nodularity, and focal areas of wall thickening may warrant surgical intervention.

Biomarkers and Algorithms

The use of serum biomarkers is a key component in the assessment of women with pelvic masses. They have been used alone, in combination, and with imaging findings to develop various tools for preoperative risk stratification of women with pelvic masses.

CA125 is the most commonly used biomarker in the detection and surveillance of ovarian cancer. This glycoprotein was identified as a marker for EOC when it was detected by murine monoclonal antibody (OC125) that reacted with tumor cells of patients with EOC [17]; about 80% of all women with EOC have an elevated serum level of CA125. The sensitivity for predicting EOC in women with a pelvic mass based on an elevated CA125 alone ranges from 43% to 81% [18–23], and the specificity can be limited. CA125 is an epithelial antigen that is produced by mesothelial cells that line the peritoneum, pleura, and pericardium. Benign conditions that may affect any of these surfaces may also increase serum levels of CA125. Common confounders that can increase serum CA125 in women being evaluated for pelvic masses include menses, pregnancy, fibroids, endometriosis, cirrhosis, and congestive heart failure.

Human epididymis protein 4, or HE4, is a novel serum biomarker for EOC. Comprising two whey acidic protein domains and a 4 disulfide core, it is overexpressed by EOC tumors, causing elevated serum levels [24]. The sensitivity of HE4 is similar to CA125 for detecting malignancy in women with pelvic masses, but it is less likely to be elevated falsely by benign conditions; it has been used to differentiate endometriomas from malignant ovarian tumors [19, 24]. In addition, a subset of women with EOC do not have elevated serum CA125 but do have elevated HE4 [22, 25]. This finding has led to the consideration that using CA125 and HE4 tests together may provide improved sensitivity for predicting EOC in women with pelvic masses.

In a prospective study evaluating multiple tumor markers alone and in combination among women undergoing surgery for a pelvic mass, Moore et al. [22] reported a sensitivity of 72.9% (specificity of 95%) for HE4. In the same study, CA125 had a sensitivity of 43.3% (specificity 95%). The two serum values in combination achieved a sensitivity of 76.4% at a set specificity of 95%, higher than either test alone [22]. This study led to the development of the Risk of Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA), a scoring system incorporating serum values of CA125 and HE4 in combination with menopausal status. When applied to women with an identified pelvic mass, the ROMA™ score divides women into low-risk and high-risk categories.

The ROMA™ score was first evaluated as a preoperative risk stratification tool in a prospective study that enrolled 531 patients scheduled for surgery for a pelvic mass. In this study population, 93.8% of ovarian cancers were correctly classified as high-risk [26]. In a second validation study, 472 women undergoing surgery for a pelvic mass were evaluated with the ROMA score. In this multicenter prospective trial, the ROMA™ score achieved a sensitivity of 92.3% and specificity of 76% for detecting EOC in postmenopausal women, and 100% sensitivity and 74.2% specificity in premenopausal women. The negative predictive value of the ROMA™ in all women was 99% [27••]. Based on these results, the authors recommend the use of the ROMA™ score as a tool for preoperative risk stratification, and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved the ROMA™ for this indication. Women in the high-risk category should be referred to gynecologic oncologists for their surgery, to achieve improved outcomes for women with a diagnosis of ovarian cancer.

Another commonly used tool for preoperative risk stratification is the Risk of Malignancy Index (RMI), which takes into consideration serum CA125 levels, menopausal status, and US findings. When first introduced, this tool achieved a sensitivity of 95.1% with a specificity of 76.5% [28]. However, the value of sonography is variable based upon the experience of sonographers and radiologists, so these results have been difficult to replicate [29]. When compared head-to-head with RMI in a prospective multicenter trial, the ROMA™ score demonstrated a significantly higher sensitivity (94.3% vs 84.6%) at a set specificity of 75% for both EOC and tumors of low malignant potential (LMP) [27••].

Another tool approved by the FDA for use in determining the need for referral to a gynecologic oncologist is the OVA1™ test, a multivariate index biomarker assay. Utilizing the improved sensitivities of more than one serum biomarker, the test includes five immunoassays: CA 125-II, transthyretin (prealbumin), apolipoprotein A1, beta 2 microglobulin, and transferrin [30••]. The results are interpreted by proprietary software from Vermillion Inc., and Quest Diagnostics generates an OVA1 score that varies according to the patient’s menopausal status. This assay was evaluated prospectively in a multicenter trial that enrolled 590 women scheduled for surgery for an ovarian mass. When used in conjunction with physician assessment, the multivariate index assay improved sensitivity to 92% compared with 72% for physician assessment alone, but specificity decreased from 83% to 42% [30••].

Organizational Guidelines

Significant morbidity and mortality are associated with the diagnosis of EOC, and outcomes have been shown to improve when patients are triaged to gynecologic oncologists early in their care. As a result, guidelines for referring a woman with a pelvic mass to a gynecologic oncologist have been established by both the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG, Table 1) and the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists (SGO, Table 2).

These guidelines were validated by Im et al. [31], who examined 1,035 women who underwent surgical exploration at six referral centers. They found that 30.7% of the cases were primary ovarian cancers, with an additional 4.8% being metastases to the ovary. The guidelines identified 70% of the malignancies in premenopausal patients and 94% in postmenopausal women. The positive predictive value when applying the referral criteria was 33.8% for premenopausal women and 59.5% for postmenopausal women, showing possible over-referral of benign pelvic masses, though many of these patients were referred for pelvic mass and positive family history alone. The negative predictive value was 92% for premenopausal women and 91.1% for postmenopausal women [31].

These referral guidelines utilize CA125 serum levels, and as newer biomarkers and risk stratifications tools are developed, they must be considered in conjunction with published guidelines in an effort to improve the accuracy of clinical decision making when referring to specialists.

In the trial that validated the OVA1 test, the authors also compared their results with the ACOG and SGO referral guidelines in a separate publication. In their study population of 590 women, the OVA1 had a sensitivity of 94%, compared with 77% for the guidelines alone. The negative predictive value of OVA1 was 93%, compared with 87% for the guidelines. However, the guidelines had a higher specificity (68% vs 35%) and positive predictive value (52% vs 40%), so use of the OVA1 test could result in more benign surgeries being done by gynecologic oncologists [31].

Special Considerations

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Laparotomy is the standard of care for surgical staging and cytoreduction for EOC. However, minimally invasive surgery provides benefits to patients such as decreased pain and morbidity, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery. Because most women with a pelvic mass have benign disease, a minimally invasive approach is reasonable under appropriate circumstances.

The goal of any surgery for a pelvic mass should be the intact removal of the mass, which can be achieved using techniques for a controlled rupture within the confines of an endoscopic specimen bag. However, tumors larger than 10 cm can be technically difficult to remove laparoscopically. Among 186 women who underwent laparoscopy for pelvic masses 10 cm or larger in size, 174 had their surgery completed laparoscopically. Surgeons converted to laparotomy for technical difficulties in 7 patients or incidental malignancies requiring staging in the other 5. However, cystic rupture and spillage occurred in 121 cases [32]. The implications of a ruptured benign cyst are negligible, but rupture of a stage I ovarian malignancy results in an increase in stage and may lead to a worse disease-free survival [33].

Women with evidence of advanced ovarian cancer and those who are otherwise in a high-risk category based on stratification tools should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for their surgery. For women in the low-risk category, the decision regarding the surgical approach will depend upon a number of factors, such as surgeon experience with laparoscopic surgery, the size of the pelvic mass, and the ability to determine malignancy intraoperatively.

Pregnancy

With the increasing use of obstetric ultrasound, asymptomatic ovarian masses are being identified more often, with published incidences as high as 1 in 81 pregnancies [34, 35]. The differential diagnosis for a pelvic mass in pregnancy is essentially the same as in nonpregnant premenopausal women; functional cysts and persistent corpus luteum are the most common findings. Malignancy is rare and is only found in 1–8% of pregnancy-associated masses [34, 35].

Most pelvic masses in pregnancy can be observed and will regress without intervention. Because CA125 can be falsely elevated in pregnancy, an elevated serum level must be considered carefully in context with the rest of the clinical scenario before pursuing surgery [36].

Surgery for pelvic masses can be considered in the second trimester based on concern for malignancy, intractable pain, or high potential for rupture or torsion. There is no standard surgical approach, but for skilled laparoscopic surgeons, the benefits of laparoscopy over laparotomy may outweigh the risks [37].

Premenarchal and Adolescent Females

Ovarian malignancies are quite rare in children, but young girls can present with pelvic masses. If surgical intervention is warranted, the standard of care calls for ovarian preservation, if at all possible. One of the most common diagnoses in a young girl with a pelvic mass is ovarian torsion, which usually can be managed with laparoscopic detorsion of the ovary. Although the ovary often appears edematous and enlarged, it is very rarely malignant, with rates of only 1–3.5% [38]. If no obvious signs of metastatic disease are seen, the ovary should be left in situ and monitored postoperatively with ultrasound.

For young women with an asymptomatic simple cyst less than 8 cm, observation is the standard of care. In the setting of pain that is not felt to be consistent with torsion, aspiration can be considered; these cysts have a low risk of recurrence [39].

In this age group, complex or solid masses raise concern about malignancy, most commonly germ cell or sex-cord stromal tumors. Accordingly, tumor markers for nonepithelial ovarian cancers should be obtained in addition to CA 125 and HE4, including total inhibin plus inhibin A&B, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alpha-fetoprotein, and beta-HCG. Because the risk of malignancy in this age group is so high, these patients should be referred to specialists for their surgery.

Fertility Preservation

Fertility-preserving surgery for pelvic masses is the standard of care for benign neoplasms. It is also standard for young women with ovarian tumors of low malignant potential (LMP), germ cell and sex-cord stromal tumors, and some patients with low-grade, stage I EOC. However, surgery for malignancies in women of reproductive age should be undertaken with a multidisciplinary approach including both oncologic and reproductive experts. Therefore, preoperative consultation by a gynecologic oncologist is crucial for young women in a high-risk category [40, 41].

Conclusions

The diagnosis of a pelvic mass is common among women, most of whom will have benign disease. For the minority of women with an ovarian malignancy, outcomes are improved when their surgery is performed by specialists in referral centers. Nevertheless, fewer than 50% of women have their initial cancer surgery performed by a gynecologic oncologist [3, 4]. Considerations of surgical intervention for a pelvic mass should therefore be based upon both symptoms and risk of malignancy.

An increasing number of tools are available to gynecologists for preoperative risk stratification of women with pelvic masses, including imaging, biomarkers and algorithms, and referral guidelines established by professional societies. When choosing which tools to use, the clinician should take into account a test’s sensitivity and specificity, cost, and availability. The ROMA™ score is a reasonable adjunct to the history, physical examination, and imaging. It provides excellent sensitivity in detecting EOC, and its superior specificity and negative predictive value allow patients with benign disease to remain in their community for their surgery.

References

Recently published papers of interest have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Curtin JP. Management of the adnexal mass. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;55(3 Pt 2):S42–6.

DeFrances CJ, Hall MJ. 2005 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Adv Data. 2007;385:1–19.

Carney ME, Lancaster JM, Ford C, Tsodikov A, Wiggins CL. A population-based study of patterns of care for ovarian cancer: who is seen by a gynecologic oncologist and who is not? Gynecol Oncol. 2002;84(1):36–42.

Earle CC, Schrag D, Neville BA, Yabroff KR, Topor M, Fahey A, et al. Effect of surgeon specialty on processes of care and outcomes for ovarian cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(3):172–80.

Goff BA, Matthews BJ, Wynn M, Muntz HG, Lishner DM, Baldwin LM. Ovarian cancer: patterns of surgical care across the United States. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103(2):383–90.

McGowan L, Lesher LP, Norris HJ, Barnett M. Misstaging of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65(4):568–72.

Paulsen T, Kjaerheim K, Kaern J, Tretli S, Trope C. Improved short-term survival for advanced ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal cancer patients operated at teaching hospitals. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16 Suppl 1:11–7.

Guidelines for referral to a gynecologic oncologist: rationale and benefits. The Society of Gynecologic Oncologists. Gynecol Oncol 2000 Sep;78(3 Pt 2):S1-13.

ACOG Practice Bulletin. Management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(1):201–14.

Goff BA, Mandel LS, Drescher CW, Urban N, Gough S, Schurman KM, et al. Development of an ovarian cancer symptom index: possibilities for earlier detection. Cancer. 2007;109(2):221–7.

Finch A, Beiner M, Lubinski J, Lynch HT, Moller P, Rosen B, et al. Salpingo-oophorectomy and the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. JAMA. 2006;296(2):185–92.

Aarnio M, Sankila R, Pukkala E, Salovaara R, Aaltonen LA, de la Chapelle A, et al. Cancer risk in mutation carriers of DNA-mismatch-repair genes. Int J Cancer. 1999;81(2):214–8.

Brinton LA, Lamb EJ, Moghissi KS, Scoccia B, Althuis MD, Mabie JE, et al. Ovarian cancer risk associated with varying causes of infertility. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(2):405–14.

Padilla LA, Radosevich DM, Milad MP. Limitations of the pelvic examination for evaluation of the female pelvic organs. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88(1):84–8.

• Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, Benacerraf B, Benson CB, Brewster WR, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology 2010;256(3):943-54. This article describes the new recommendations from the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound for the management of an ovarian cyst.

Kawaguchi R, Tsuji Y, Haruta S, Kanayama S, Sakata M, Yamada Y, et al. Clinicopathologic features of ovarian cancer in patients with ovarian endometrioma. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34(5):872–7.

Bast Jr RC, Feeney M, Lazarus H, Nadler LM, Colvin RB, Knapp RC. Reactivity of a monoclonal antibody with human ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 1981;68(5):1331–7.

Einhorn N, Bast Jr RC, Knapp RC, Tjernberg B, Zurawski Jr VR. Preoperative evaluation of serum CA 125 levels in patients with primary epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67(3):414–6.

Hellstrom I, Raycraft J, Hayden-Ledbetter M, Ledbetter JA, Schummer M, McIntosh M, et al. The HE4 (WFDC2) protein is a biomarker for ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63(13):3695–700.

Maggino T, Gadducci A, D’Addario V, Pecorelli S, Lissoni A, Stella M, et al. Prospective multicenter study on CA 125 in postmenopausal pelvic masses. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;54(2):117–23.

Malkasian Jr GD, Knapp RC, Lavin PT, Zurawski Jr VR, Podratz KC, Stanhope CR, et al. Preoperative evaluation of serum CA 125 levels in premenopausal and postmenopausal patients with pelvic masses: discrimination of benign from malignant disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159(2):341–6.

Moore RG, Brown AK, Miller MC, Skates S, Allard WJ, Verch T, et al. The use of multiple novel tumor biomarkers for the detection of ovarian carcinoma in patients with a pelvic mass. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;108:402–8.

Skates SJ, Horick N, Yu Y, Xu FJ, Berchuck A, Havrilesky LJ, et al. Preoperative sensitivity and specificity for early-stage ovarian cancer when combining cancer antigen CA-125II, CA 15-3, CA 72-4, and macrophage colony-stimulating factor using mixtures of multivariate normal distributions. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(20):4059–66.

Drapkin R, von Horsten HH, Lin Y, Mok SC, Crum CP, Welch WR, et al. Human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) is a secreted glycoprotein that is overexpressed by serous and endometrioid ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65(6):2162–9.

Rosen DG, Wang L, Atkinson JN, Yu Y, Lu KH, Diamandis EP, et al. Potential markers that complement expression of CA125 in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99(2):267–77.

Moore RG, McMeekin DS, Brown AK, Disilvestro P, Miller MC, Allard WJ, et al. A novel multiple marker bioassay utilizing HE4 and CA125 for the prediction of ovarian cancer in patients with a pelvic mass. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(1):40–6.

•• Moore RG, Miller MC, Disilvestro P, Landrum LM, Gajewski W, Ball JJ, et al. Evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm in women with a pelvic mass. Obstet Gynecol 2011 Aug;118(2, Part 1):280-8. This article examines the use in a low-risk population of the ROMA test to assess the risk that a pelvic mass represents an ovarian malignancy. This test was recently cleared by the US FDA.

Jacobs I, Oram D, Fairbanks J, Turner J, Frost C, Grudzinskas JG. A risk of malignancy index incorporating CA 125, ultrasound and menopausal status for the accurate preoperative diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97(10):922–9.

Bailey J, Tailor A, Naik R, Lopes A, Godfrey K, Hatem HM, et al. Risk of malignancy index for referral of ovarian cancer cases to a tertiary center: Does it identify the correct cases? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16 Suppl 1:30–4.

•• Ueland FR, DeSimone CP, Seamon LG, Miller RA, Goodrich S, Podzielinski I, et al. Effectiveness of a multivariate index assay in the preoperative assessment of ovarian tumors. Obstet Gynecol 2011 Jun;117(6):1289-97. This article examines the use of a five-marker combination for determining the likelihood that a pelvic mass is malignant. This test was recently cleared by the US FDA.

Im SS, Gordon AN, Buttin BM, Leath 3rd CA, Gostout BS, Shah C, et al. Validation of referral guidelines for women with pelvic masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(1):35–41.

Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Bergamini V, Uccella S, Siesto G, Franchi M, et al. Should adnexal mass size influence surgical approach? A series of 186 laparoscopically managed large adnexal masses. BJOG. 2008;115(8):1020–7.

Bakkum-Gamez JN, Richardson DL, Seamon LG, Aletti GD, Powless CA, Keeney GL, et al. Influence of intraoperative capsule rupture on outcomes in stage I epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):11–7.

Leiserowitz GS. Managing ovarian masses during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61(7):463–70.

Whitecar MP, Turner S, Higby MK. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: a review of 130 cases undergoing surgical management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(1):19–24.

Schmeler KM, Mayo-Smith WW, Peipert JF, Weitzen S, Manuel MD, Gordinier ME. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: surgery compared with observation. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 1):1098–103.

Hoover K, Jenkins TR. Evaluation and management of adnexal mass in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 May 13.

Oltmann SC, Fischer A, Barber R, Huang R, Hicks B, Garcia N. Pediatric ovarian malignancy presenting as ovarian torsion: incidence and relevance. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(1):135–9.

Hayes-Jordan A. Surgical management of the incidentally identified ovarian mass. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2005;14(2):106–10.

Billmire DF. Malignant germ cell tumors in childhood. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2006;15(1):30–6.

Eskander RN, Randall LM, Berman ML, Tewari KS, Disaia PJ, Bristow RE. Fertility preserving options in patients with gynecologic malignancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(2):103–10.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 280: The role of the generalist obstetrician-gynecologist in the early detection of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(6):1413-6.

Disclosure

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

MacLaughlan, S., Cronin, B. & Moore, R.G. Evaluation and Management of Women Presenting with a Pelvic Mass. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep 1, 10–15 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13669-011-0003-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13669-011-0003-2