Abstract

Purpose of Review

The increase in wildfire prevalence and severity has generated alarm as wildfire air pollution is associated with significant respiratory morbidity. We aim to summarize the pathophysiology of wildfire air pollution causing lung disease, current knowledge of pulmonary health effects, and precautionary guidance to the public. We also propose specific guidance for high-risk patients during wildfires.

Recent Findings

Health effects of wildfire air pollution have been difficult to evaluate; however, respiratory morbidity has been firmly established including exacerbation of known pulmonary disease and increased hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and dispensation of reliever medications. Public health agencies and officials provide wildfire preparation recommendations and active updates to the public during a wildfire event but fail to address specific needs of chronic lung disease patients considered high-risk for pulmonary complications. To fill this void, it is increasingly important for pulmonary physicians to understand wildfire-related pulmonary morbidity and provide specific guidance to their patients.

Summary

This review summarizes the health effects of wildfire air pollution and provides guidance for the management of high-risk patients during wildfires.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The escalation of enlarging and prolonged wildfires is alarming in recent years. Air pollution caused by wildfires leads to a multitude of pulmonary complications. Presently, preventative guidance stems from national health organizations and agencies; however, there is a greater call for physicians to be actively involved in preemptive counseling of high-risk patients. Physicians must be prepared to manage high-risk and previously healthy patients following exposure to wildfires [1, 2]. We summarize current knowledge of wildfires pertinent to pulmonary health and propose an approach toward mitigation and treatment of pulmonary complications.

An increase in wildfire destruction is noted both nationally and globally [3]. In the USA, the National Interagency Coordination Center reports firefighting suppression costs soaring to over 2.2 trillion dollars and an increase to nearly 10 million acres burned per year representing a tenfold increase in acreage since the 1980s [4]. Internationally, there are 3 to 6 million kilometers burned per year [5] with an estimated 339,000 annual deaths worldwide attributable to wildfires [6].

Wildfires are in part a natural phenomenon for the renewal of some ecosystems [2, 5], but climate change and human influence are increasing the frequency, size, pace of spread, and destruction of wildfires [7, 8]. Climate change alters natural conditions causing drought, strong winds, and higher temperatures which contribute to an environment conducive for ignitions [3] effectively causing a longer fire season and leading to wildfires in atypical areas [7]. Loss of forest and production of greenhouse gas during wildfires further perpetuate climate change [3]. Most alarming is that human-driven climate change alone accounts for nearly half of all acres burned from 1979 to 2015 [9]. Further, human ignitions pose a greater risk than natural lightning-related ignitions by causing fires in atypical, high moisture areas outside of fire season and often causing large-scale fires responsible for greater destruction [7].

Smoke Toxicology

Wildfires not only cause immediate danger due to flames but also produce air pollution in the form of particulate matter (PM) and hazardous gases which may spread over thousands of miles. When produced by human activities, these pollutants are regulated under the Clean Air Act due to their ill effects [1, 10]. The PM and hazardous gas content from wildfires is highly variable which creates a challenging landscape for researchers to clearly define adverse health effects from wildfires. Air pollution is dependent on fuel type ranging from natural vegetation to man-made materials such as plastic, glass, cement, asbestos, and other substances which are prevalent along the expanding rural urban interface experiencing greater incidence of wildfires. Factors such as moisture content, fire temperature, wind conditions, and topography also play a role in wildfire air pollution composition and spread [5].

PM has been the primary focus of research for wildfire health effects [3]. PM is a term for small particles and droplets released by chemical reactions. PM may occur from both natural processes such as volcanoes and fires and human activities such as industrial processes or vehicle emissions. PM is categorized by size from < 10 μm (PM10) or “coarse,” < 2.5 μm (PM2.5) or “fine,” and < 0.1 μm (PM0.1) or “ultrafine” [10]. Health effects of PM are studied based on size rather than composition due to highly variable content and lack of data linking specific PM composition to health outcomes [5]. Ninety percent of PM produced from wildfires is PM2.5 which is the most dangerous PM type due to its ability to be inhaled to all areas of the respiratory tract and even translocate into the circulatory system [11]. Wildfires are well-known to cause a significant transient increase in PM2.5 for greater than 2 days which has been termed as a “smoke wave” [12].

Hazardous gases produced by wildfires include ozone, carbon monoxide (CO), nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, benzene, and volatile organic compounds which are difficult to measure [3]. Although a secondary focus, adverse effects such as generalized symptoms of eye or skin irritation, drowsiness, and cough are established effects for some of these pollutants [5], in addition to specific toxicities such as CO poisoning [3] or possible carcinogenic effects [5].

Proposed Mechanisms of Pulmonary Disease

PM may lead to a range of health effects through different mechanisms of disease not clearly established in the literature [1]. Zhong et al. and Kim et al. suggest an endotoxin-like effect of coarse particles, while Cascio proposes coarse particle interaction with pulmonary neural receptors; both explanations account for observed autonomic effects of increased blood pressure and heart rhythm changes upon initial smoke exposure [1, 13, 14]. Cascio further surmises that smaller, inhaled particles likely cause oxidative reactions locally at the alveolar capillary level or systemically after translocation across the alveolar membrane leading to an array of health effects [1]. Of note, animal studies have shown lower number of lung macrophages, increased inflammatory cells and cytokines, greater antioxidant depletion, and reduced lung mechanics after wildfire derived PM exposure [15].

Adverse Health Outcomes

Establishing specific health outcomes of wildfires has been difficult not only due to variable content of wildfire smoke but also due to variable characteristics of an exposed population such as duration and intensity of exposure [2]. Studies have observed firefighters [16] and local populations during wildfire events [8], but studying long-term exposure continues to be challenging [3].

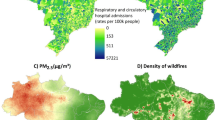

The literature supports a multitude of adverse pulmonary outcomes during wildfire events. On fire days, there is an increase in reported pulmonary symptoms such as cough and wheeze [8] with a significant increase in emergency department (ED) visits, physician visits, and hospitalizations for pulmonary complaints and an increase in dispensation of pulmonary reliever medication and oral steroids [15]. Specifically, asthma exacerbations occur more frequently on fire days with an Australian study showing a 2.4 × increase in asthma-related ED visits on fire days compared to non-fire days [8]. Asthma exacerbations are worse specifically with wildfire PM rather than ambient urban PM, possibly due to composition and intensity of the wildfire PM [3]. There is also an increase in COPD exacerbations with some requiring hospitalization [15] along with increased incidence of bronchitis and pneumonia [5, 8, 15]. Some data also supports increase in upper respiratory tract infections [17]. Data otherwise is lacking for specific pulmonary diseases, and more information is needed. Pulmonary morbidity due to wildfires is disproportionately endured by the elderly, women, and those of lower socioeconomic class [1].

Firefighters are a population that may be studied for long-term pulmonary effects from wildfire PM exposure. Unfortunately, there is no standard respiratory safety equipment for outdoor fires, and respirators are otherwise impractical and rarely used due to self-perceived health [2]. Liu et al. studied lung function in California firefighters and demonstrated declines in forced vital capacity, forced expiratory volume over 1 s, and increased airway responsiveness [18]. Navarro also predicted total PM exposure of firefighters and demonstrated a likely 8 to 43% increase in lung cancer incidence [16].

Cardiovascular (CV) outcomes are worse in the setting of urban PM; however, data on adverse CV outcomes due to wildfire PM is mixed [15]. Among positive studies, results suggest an increase in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, increase in hospitalizations for myocardial infarction [19], increase in ED visits for congestive heart failure [8], worsening hypertension, and a possible association with cerebrovascular disease and stroke [15].

Data also suggests an array of other adverse health outcomes related to wildfire PM including low birth weight of fetuses with mothers exposed to wildfire smoke in the second or third trimester [20], increased ambulance dispatches for diabetes, increased incidence of influenza [3], increased markers of systemic inflammation, changes in bone marrow content, and reported decreased physical strength and overall health [8]. Table 1 summarize adverse health outcomes from wildfire exposure.

Direct exposure to an active wildfire may also cause direct harm in the form of burns, physical injuries, dehydration, heat stroke, or death. Heavy smoke exposure can also cause eye irritation and corneal abrasions. Involvement in a catastrophic wildfire can also cause immediate and long-lasting mental health impacts [3]. Other unknown health effects may occur because of utilizing water contaminated with ash, fire retardant, and dead animals [1, 3]. There is an observed increase in all-cause mortality due to nonaccidental death on fire days, although the exact etiology is unclear [15].

Risk Assessment

Public health agencies and medical organizations provide accessible online education regarding emergency preparedness and safety measures prior to wildfire events, although there is increasing expectation for direct physician guidance to patients [2]. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the American Lung Association (ALA), the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and multiple state health departments have accessible online resources for the public; however, only the EPA offers specific training online for healthcare professionals [2, 11, 21, 22].

During a wildfire event, public health officials assume the primary role of providing real-time updates and safety guidance through clearly established lines of communication. Recently, wildfire experts have been deployed to areas with ongoing fires to provide current, short-, and long-term smoke forecasts via public news casts to ensure public safety, although there is a growing need to reinforce these collaborative efforts. The public may also receive updated through AirNow which is a novel online tool that utilizes the US air quality index (AQI) to report current levels of air pollution. The AQI is a measurement of PM2.5, PM10, and ozone in a specific region which correlates to recommendations regarding outdoor activities. It is imperative to monitor AQI in the setting of a wildfire due to evolving conditions and ability of smoke to spread thousands of miles toward unsuspecting inhabitants. AirNow’s Fires: Current Conditions is intended to provide updated information in quickly changing wildfire conditions; however, updates may still lag real-time occurrences making awareness of public updates by health experts critical [2].

Safety Measures

The public is encouraged to utilize educational resources prior to a wildfire event for adequate preparation [11]. Emergency supplies should include clean water, food, medications, and emergency power sources. The public should also plan a means to receive updated wildfire information, air quality reports, and advisories [21]. Consideration may be given to upgrading heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) units for improved air filtration, purchasing a portable air cleaner with a high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter, and obtaining a particulate respirator termed “N95” or “P100” masks (Fig. 1). Review of wildfire education prior to a wildfire will also allow for preparatory actions if advisories dictate limited outdoor activity, strictly indoor activity, or even evacuation [11], represented in Fig. 2.

A particular matter respirator should be labeled as N95 or higher and include two tightly secured straps. An N95 must have a tight seal to function properly and therefore cannot be worn by men with beards or by children [11]. Patients with chronic lung or heart disease may become short of breath with use [3]

The graphics emphasizes that preemptive wildfire education, preparation, and knowledge of current information are crucial in taking appropriate action during a wildfire event. Evacuation, strictly indoor activity, or limited outdoor activity may be advised during an active wildfire pending proximity to the fire and air quality index which will be continually updated by local news sources and AirNow.gov

Limited outdoor activity may be advised if the air quality index is poor. According to the EPA, the dose of air pollution a patient is exposed to is proportional to the concentration of air pollution (best represented by the AQI), a person’s minute ventilation, and the duration of exposure. Therefore, patients may be advised to limit physical exertion to minimize minute ventilation and to spend minimal time outdoors [11]. N95 masks are also recommended while outdoors to filter harmful PM, thus reducing the concentration of air pollution. Although universally recommended, N95 masks may provide false reassurance as a tight-fitting N95 mask is required to properly filter PM and cannot be used by those with beards or by children [21], offer no protection against hazardous gases [2], and may also cause shortness of breath for those with heart or lung disease [3]. If an individual is not outdoors but driving a vehicle, it is also recommended to keep windows up and switch the air conditioning to “recirculate mode” to avoid infiltration of air pollution to the vehicle [11, 21, 22].

Strictly indoor activity may be advised if the AQI is dangerously high. Although potentially cost prohibitive, ideal interventions include preemptive inspection of the HVAC system with upgrade to a higher efficiency filter [11] and use of an air purifier equipped with a HEPA filter. Despite significant reduction in PM, the filters offer no protection against hazardous gases, so inhabitants must remain vigilant [3, 11]. The ALA and EPA also recommend designating a “clean room” where an air filter is placed, and damp towels may be placed against window and door edges for times of extreme air pollution [11, 21]. It is also recommended to refrain from vacuuming or burning anything indoors including cigarettes or candles [21].

Evacuation may be necessary in extreme conditions to avoid direct dangers of flames. Evacuation planning is paramount due to challenges such as increased cost, uncertain duration, and persistent air pollution despite significant distance from the fire. Furthermore, dense air pollution may cause poor visibility potentially causing traffic accidents. For those actively involved in extreme conditions in the immediate wildfire area such as firefighters, adequate personal protective equipment, hydration, rest, and psychological support are needed [3]. Continued use of N95s is needed even in cleanup efforts while managing wildfire ash [21].

Certain populations are at higher risk for health complications because of exposure to air pollution from wildfires. These at-risk populations include outdoor workers, children, elderly persons, pregnant women, and patients with chronic lung disease, and CV disease [1], and diabetes [23]. These sensitive groups are advised to strictly adhere to public advisories and consider physician consultation prior to a wildfire due to potential exacerbations of underlying disease [11, 21]. Physicians may educate patients regarding exacerbation symptoms and medication to have immediately available for emergency use [11]. It remains critically important that all healthcare professionals including physicians, nurses, and health educators deliver a consistent message of strict adherence to public advisories during wildfires and recommended at-home interventions [2]. At-risk populations should also be excluded in cleanup activities particularly in areas where hazardous waste may be burned [21].

Actions for Physicians

Although generalized information is readily available for the public, little is published regarding preemptive counseling or post-exposure treatment for patients with specific pulmonary diseases aside from avoiding, preparing for, and treating exacerbations. Furthermore, there are no current recommendations regarding surveillance imaging or pulmonary function testing for individuals with high intensity or recurrent exposure to wildfire air pollution despite evidence for increased incidence of lung cancer or decreased lung function [2]. Table 2 summarizes current recommendations for physicians supported by national health organizations and medical societies.

Conclusion

Worsening wildfires pose a persistent risk to human health. Public policy to address climate change is needed as projections indicate that small reductions in global temperature may positively impact mortality, morbidity, environmental impact, and overall cost savings [3]. Further investigations of effective public interventions to minimize climate impact are needed. Meanwhile, ongoing research is also necessary to learn how composition of wildfire smoke and duration of exposure impact long-term health outcomes, particularly for those with chronic lung disease. This research may be translated to actionable public health interventions and physician-based approaches during wildfire events [2]. From a global perspective, more information on wildfire smoke exposure and subsequent health impacts are greatly needed to study populations in developing areas frequently facing wildfire such as Africa and Southeast Asia which are underrepresented in current literature [1] and experience a disproportionate wildfire-related mortality [6].

The growing threat of wildfires is creating alarm within the medical community leading to publications in high-impact journals such as NEJM in 2020 and published workshop proceedings by the ATS in 2021. Further, climate change is a widely accepted cause of worsening wildfires; however, Abatzoglou and Williams in 2016 demonstrated that human-driven climate change is responsible for nearly half of all acres burned in recent decades. As clinicians caring for patients with lung disease, it is critical to remain informed of newly surfacing research findings, prevention strategies, management recommendations, and evolving legislation that can highly impact our patients.

Abbreviations

- ALA :

-

American Lung Association

- ATS :

-

American Thoracic Society

- CO :

-

Carbon monoxide

- CV :

-

Cardiovascular

- ED :

-

Emergency department

- EPA :

-

Environmental Protection Agency

- HVAC :

-

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning

- HEPA :

-

High efficiency particulate air

- PM:

-

Particulate matter

- USA:

-

Unites States

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Cascio WE. Wildland fire smoke and human health. Sci Total Environ. 2018;624:586–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.086.

Rice MB, Henderson SB, Lambert AA, Cromar KR, Hall JA, Cascio WE, Smith PG, Marsh BJ, Coefield S, Balmes JR, Kamal A. Respiratory impacts of wildland fire smoke: Future challenges and policy opportunities. An official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021 Jun;18(6):921-30. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202102-148ST. This paper describes the proceedings from an American Thoracic Society workshop involving an expert panel on wildland fires and describes the science of wildland fires, health effects, management strategies, and future actions needed.

Xu R, Yu P, Abramson MJ, Johnston FH, Samet JM, Bell ML, Haines A, Ebi KL, Li S, Guo Y. Wildfires, global climate change, and human health. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(22):2173-81. This high impact review article in the New England Journal of Medicine comprehensively describes safety precautions during wildfires, potential morbidity and mortality associated with wildfires, and factors contributing to worsening wildfires across the globe.

Ahrens M, Evarts B. Fire loss in the United States during 2020 (NFPA ® ) Key Findings. 2021.

Youssouf H, et al. Quantifying wildfires exposure for investigating health-related events. Atmos Environ. 2014;97C:239–51.

Johnston FH, et al. Estimated global mortality attributable to smoke from landscape fires. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(5):695–701. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104422.

Nagy RC, Fusco E, Bradley B, Abatzoglou JT, Balch J. Human-related ignitions increase the number of large wildfires across US ecoregions. Fire. 2018;1(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire1010004.

Liu JC, Pereira G, Uhl SA, Bravo MA, Bell ML. A systematic review of the physical health impacts from non-occupational exposure to wildfire smoke. Environ Res. 2015;136:120-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2014.10.015.

Abatzoglou JT, Williams AP. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(42):11770–5. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1607171113. The authors of this influential paper were the first to demonstrate that human-driven climate change accounts for nearly half of acres burned in the past several decades, suggesting a greater need for legislative action to prevent climate change.

Anderson JO, Thundiyil JG, Stolbach A. Clearing the air: a review of the effects of particulate matter air pollution on human health. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(2):166–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-011-0203-1.

Cascio W, Mirabelli M, Sacks J, Stone SL, Wayland M, Wildermann E. Wildfire smoke and your patients’ health. United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2021. This training course offered by the EPA is the only physician-specific tool for improving knowledge about wildfires and subsequent health impacts with specific advice for preventative patient counseling.

Liu JC, et al. Particulate air pollution from wildfires in the Western US under climate change. Clim Change. 2016;138(3–4):655–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1762-6.

Zhong J, et al. Endotoxin and β-1,3-d-glucan in concentrated ambient particles induce rapid increase in blood pressure in controlled human exposures. Hypertension. 2015;66(3):509–16. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05342.

Kim YH, Tong H, Daniels M, Boykin E, Krantz QT, McGee J, Hays M, Kovalcik K, Dye JA, Gilmour MI. Cardiopulmonary toxicity of peat wildfire particulate matter and the predictive utility of precision cut lung slices. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2014;11(1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8977-11-29.

Reid CE, Brauer M, Johnston FH, Jerrett M, Balmes JR, Elliott CT. Critical review of health impacts of wildfire smoke exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124(9):1334-43. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1409277.

Navarro K. Working in Smoke:: Wildfire Impacts on the Health of Firefighters and Outdoor Workers and Mitigation Strategies. Clin Chest Med. 2020;41(4):763-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2020.08.017.

Tinling MA, West JJ, Cascio WE, Kilaru V, Rappold AG. Repeating cardiopulmonary health effects in rural North Carolina population during a second large peat wildfire. Environ Health. 2016;15(1):1-2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-016-0093-4.

Liu D, Tager IB, Balmes JR, Harrison RJ. The effect of smoke inhalation on lung function and airway responsiveness in wildland fire fighters. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:1469-.

Haikerwal A, Akram M, Del Monaco A, Smith K, Sim MR, Meyer M, Tonkin AM, Abramson MJ, Dennekamp M. Impact of fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) exposure during wildfires on cardiovascular health outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(7):e001653. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.114.001653.

Holstius DM, Reid CE, Jesdale BM, Morello-Frosch R. Birth weight following pregnancy during the 2003 southern California wildfires. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(9):1340–5. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104515.

American Lung Association, “Protect your health during wildfires.” www.lung.org. Last accessed: Aug 23rd, 2022. https://www.lung.org/getmedia/695663e2-bdb8-4a61-9322-02657f530b99/protect-your-health-during-wildfires-5-29-2020-(1).pdf

Jamil S, Carlos WG, Leard L, Wang A, Santhosh L, Balmes J, Seam N, Dela Cruz CS. Wildfires disaster guidance: tips for staying healthy during wildfires. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(2):P3-4. https://airnow.gov.

Rappold AG, Reyes J, Pouliot G, Cascio WE, Diaz-Sanchez D. Community vulnerability to health impacts of wildland fire smoke exposure. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51(12):6674–82. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b06200.

Acknowledgements

We thank the West Virginia Clinical and Translation Science Institute for their assistance and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was not required because this study retrieved and synthesized data from already published studies.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Environmental and Occupational Health

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stawovy, L., Balakrishnan, B. The Threat of Wildfires and Pulmonary Complications: A Narrative Review. Curr Pulmonol Rep 11, 99–105 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13665-022-00293-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13665-022-00293-7