Abstract

Amidst growing societal tensions, social media platforms become hubs of heated intergroup exchanges. According to social identity theory, group membership and the value we assign to it drive the expression of intergroup bias. Within the blooming scholarship on social and political polarization online, little attention has been paid to interreligious deliberations, despite the well-established relationship between religion and intergroup grievances. The present studies are designed to address the void in the scholarship of social identity and online religion by examining how religious identities, or the lack thereof, affect intergroup biases in the form of identity-specific topic preferences and topic-sentiment polarization. Drawing from social identity theory, five hypotheses were tested. The data for the study, a product of a natural experiment, are YouTube commentary sections featuring videos on two cases of interreligious debates between (1) Christian and Muslim or (2) Christian and atheist speakers. Using topic-sentiment analysis, a multistage method of topic modeling with latent semantic analysis and sentiment analysis, 24,179 comments, for the Christian–Muslim debates, and 52,607 comments, for the Christian–atheist debates, were analyzed. The results demonstrate normative content and identity-specific instances of topic-sentiment polarization. In terms of content, Christian–Muslim and Christian–atheist discussions are nearly completely preoccupied with theological or intellectual concepts. While interreligious polarization is robust in both debates, it appears more normative among Christians–Muslims and deeper among Christians–atheists, possibly indicating the higher stakes in the battle for moral authority. Interreligious debates on YouTube serve to uplift and defend the in-group and to delegitimize the outgroup in a broader battle for moral authority. Regardless of group affiliation, these debaters were concerned with ‘big picture’ questions of meaning and how best to address them. Stereotyping and cultural altercations appear mostly as a reaction to challenged identity characteristics, suggesting that issue-based social differences and cultural incompatibilities, often emphasized in self-report research, may be evoked as rationalizations of interreligious prejudice. Last, the successful application of topic-sentiment analysis lends support for the more systematic utilization of this method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Identity-work and its relationship with intergroup behavior have received extensive attention within the academic community. Social identity theory (SIT) argues that our social memberships are instrumental for the emergence of social identities and structure how we understand ourselves, what we believe, and how we interact with others who belong to the in-group or not (Brown 2000; Hogg et al. 1995; Tajfel and Turner 1979). Due to the inherent evaluative components of one’s social identity (Tajfel 1979; Ysseldyk et al. 2010), individuals tend to exhibit intergroup bias (Hogg and Terry 2000; Tajfel and Turner 1979).

Despite the extensive research in the context of SIT, the effect of religious membership as a social identity has been rather neglected (see Hogg et al. 2010; Ysseldyk et al. 2010). Surprising, if we consider the normative power of religion (Hogg et al. 2010; Hunsberger and Jackson 2005; Silberman 2005) and the well-established relationship with phenomena such as prejudice (Laythe et al. 2002), stereotyping (Bain et al. 2013; Edgell et al. 2016), bigotry (Eisinga, Konig, and Scheepers 1995), and intergroup conflict (Neuberg et al. 2014).

The present study seeks to contribute to research related to social identity theory and online religion by examining how (ir)religious identities contribute to online interreligious polarization. Using topic-sentiment analysis, a multistage method of topic modeling with latent semantic analysis (LSA) and sentiment analysis, YouTube commentaries for two cases of interreligious communications—(1) Christian–Muslim and (2) Christian–atheist debates—were analyzed. Provided a considerable lack of research on social identity in real-world interactions, this study takes a step forward by taking advantage of big data techniques and social media data.

Social Identity Theory

Social identity theory (SIT) emerged through the work of Tajfel (1979) and Tajfel and Turner (1979) with applications to a broad range of intergroup phenomena. SIT argues that the social categories we belong give rise to social identities, defined as “the individual’s knowledge that he belongs to certain social groups together with some emotional and value significance to him of his group membership” (Tajfel 1972: 292 in Turner 1975: 7). In turn, social identities reflect and determine members’ characteristics, practices, and behaviors (Hogg et al. 1995).

Intergroup distinctions trigger the development and establishment of social identities. In-group identification is barely feasible in the absence of an outgroup, which provides the necessary reference for what the in-group stands for and what it is not (Yuki 2003). The processes of social categorization and social comparison are key here. Categorization takes place when the in-group is rather homogeneous in distinctive aspects and, once achieved, it reproduces in-group similarity and sharpens intergroup boundaries (Hogg and Terry 2000; Turner et al. 1987; Yuki 2003). By highlighting the shared qualities and treating the members as interchangeable, certain convictions, views, ways of conduct, etc. assume prototypical value (Fiske and Taylor 2013) and give rise to normative conduct, stereotyping, concerted action, group norms, and reciprocal influence, among others (Hogg and Terry 2000; Hogg et al. 1995).

Social categorization keeps groups separate, but social comparisons ensure they are not equal. Comparisons establish the value of one’s membership over others and compel individuals to compete for favorable assessments that would deem their group as more prestigious (Hogg et al. 1995) and will grant a favorable social identity and higher self-esteem (Brown 2000; Hogg and Terry 2000; Hornsey 2008). This mechanism is often associated with intergroup antagonism as individuals are vested in earning an advantageous image by praising the in-group or denigrating the out-group (Rabbie, Schot, and Visser 1989). Studies following the “minimal group paradigm” and its variations revealed that the simple assignment of individuals into different groups prompts the emergence of positive in-group (Tajfel et al. 1971) and negative outgroup bias (Hewstone et al. 1981).

While mere categorization has some effects on intergroup bias, it does not suffice for the development of group-related normative behavior. Research on group formation and normalization processes indicates that group norms are internalized in stages, typically through socialization and cycles of social reinforcement, sanctions, and validation (van Kleef et al. 2019; Peek 2005). Authoritative texts, symbols, ritualistic practices, and common history aid the development of shared narratives (Werczberger and Azulay 2011). Additionally, intra-group interaction and group discussions are means through which individuals can negotiate viewpoints and reach explicit, agreed upon, collective norms about intergroup exchanges (Moor and Kanji 2019; Smith and Postmes 2009). Taking all the above into account, it is arguable that recently emerged social groups, which lack contexts for regular interaction among members lag in in-group processes of normalization and the development of shared narratives compared with long-established, culturally close-knit groups.

With the advent of technology, SIT finds considerable applications in the context of computer-mediated communications. An extension of SIT, known as the social identity model of deindividuation effects (SIDE) (Postmes et al. 1998; Spears and Lea 1994) purports that the conditions of anonymity and group visibility, often found in online settings, tend to promote conformity to group norms (Lea and Spears 1991; Reicher et al. 1998) and increase intergroup bias (Lea et al. 2001; Postmes et al. 1998).

Online Religion

The internet revolution brought about rapid changes on how people socialize, communicate, experience and engage with traditional social institutions. Within this booming field of research, the study of the online manifestations of religion has gotten relatively little, but important attention (Campbell 2013; Dawson and Cowan 2013). Online religion is used to denote platforms that allow microblogging and relatively unmoderated interactions among users as opposed to religion online, meaning websites sharing religious information in a top-down format (Helland 2005).

Not surprisingly, issues of identity and community have come at the forefront of online religion. Researchers have used internet data to investigate identity construction among the youth (Lövheim 2013), meaning negotiation (Campbell 2005), underrepresented religious groups (Cheong and Poon 2009), and transnational community ties (Cheong et al. 2009), among others. While online spaces offer opportunities for more fluidity in the development of identities (Lövheim 2013) and the emergence of diverse religious interpretations (Anderson 2003), the embedded uncertainty often compels individuals to lean back on traditional religious accounts (Campbell 2013). Also, it is not unusual for religious users to engage in apologetics or participate in religious debates, among other faith-affirming behaviors (Campbell 2010; Cheong et al. 2008).

Although the present paper aims to contribute to the broader scholarship of online religion, it departs from the current trends in this field in two main ways. First, unlike most of the studies that focus on single, geographically bound, intra-group religious phenomena, the present paper delves into intergroup exchanges and how they are shaped by the user’s (ir)religious identities. Online platforms, such as YouTube, can be used to shed unique light into an aspect of religious activity that it is difficult to be approached with conventional research data and methods. Second, given the nature of the hypothesized relationships and the data volume, a machine learning analytic approach has been employed as more fitting over typically preferred qualitative methods.

Present Research and Basic Hypotheses

Utilizing data available on YouTube, the present studies are designed to address the void in the scholarship of social identity and online religion by examining how religious identities, or the lack thereof, affect intergroup biases via two case studies of online interreligious debates. YouTube is characterized as a space of participatory culture(s) (Burgess and Green 2018). First launched in 2005, it rapidly became a leading video sharing and microblogging platform with more than 2B users per month and a high penetration rate across countries. Offering the strategic conditions of anonymity and deindividuation (Lea et al. 2001; Postmes et al. 1998), extensive YouTube comments’ sections also enhance group visibility (Reicher et al. 1998) and group size effects (Bond 2005), which contribute to conformity to group norms. Hence, this platform is receiving increasing attention for the study of phenomena such as online polarization (Abisheva et al. 2014; Bessi et al. 2016; Blitvich 2010), which often arise from group processes.

Interreligious debates tend to allure users from various faiths and beliefs. This paper only accounts for two types of identity-specific debates, those between (1) Christian and Muslim and (2) Christian and atheist users. By comparing how long-established (Christian and Muslim) and recently emerged identities (atheist) operate, we can tease out the role of normalization informing the users’ comments. Apart from a scholarly interest on these identities, these configurations were selected based on two additional criteria: relevance and availability. First, debates between Christians–Muslims and Christians–atheists are currently relevant due to the othering process undergoing each pair. Both Islam and atheism are deemed incompatible to Christian values (Edgell et al. 2016; Shadid and van Koningsveld 2001). Also, among atheists, it is not uncommon to attribute their parting from religion as a reaction to the Christian right (Catto and Eccles 2013; Cimino and Smith 2014; LeDrew 2013; Williamson and Yancey 2013). Second, as a testament of relevance, these two sets of debates seem to be the only that have captured enough attention online to generate workable, large-scale data.

Considering SIT, SIDE and online religion, I identify YouTube as a promising space for research on underexamined interreligious interactions and polarization. With topic-sentiment analysis, it becomes possible to capture topic-sentiment polarization in recorded communications. To clarify, topic-sentiment polarization refers to a variable dependency in which individuals react with polar sentiments (positive vs. negative) on a given topic based on their difference on a known factor, such as their (ir)religious identity. For this purpose, in-group bias is conceptualized as overstressing the positive attributes of one’s in-group, and outgroup bias as overemphasizing the unfavorable characteristics of the outgroup (Greene 2004), instead of differential treatment of in-group and outgroup members. It follows that, in the context of online interreligious debates,

H1

Individuals will be more likely to discuss topics associated with their own than the outgroup’s (ir)religious identity (reliance on in-group normative elements).

H2A

Individuals will be more likely to use positive language when they discuss topics associated with their own than the outgroup’s (ir)religious identity (positive in-group bias).

H2B

Individuals will be more likely to use negative language when they discuss topics associated with the (ir)religious identity of the other group than their own (negative out-group bias).

These hypotheses are being tested in both debates. However, the identity incongruence compels me to pose additional hypotheses, which will be presented in the context of each debate.

In sum, the present studies aspire to (1) expand our understanding of interreligious interactions and polarization as a function of (ir)religious belonging, (2) reveal converging and diverging patterns among established (Christians and Muslims) and emerging identities (atheists), and (3) develop the methodological application of topic-sentiment analysis.

Methods

Data

The data used constitute comments made in YouTube videos featuring interreligious debates. Two types of debates were selected: Christian versus Muslim and Christian versus atheist. The sampling technique is best described as purposive sampling and considered three criteria: (1) an explicit debate between Christian and atheist/Christian and Muslim, (2) a minimum number of views (> 20,000), and (3) a minimum number of comments (> 400).

The reference of the debating groups in the videos’ titles serves as a keyword search mechanism and a form of natural priming. Once located, the video content was verified for relevance; those featuring other faiths, partial debates, etc. were excluded. Next, cut-off points of minimum 20,000 views and 400 comments were used for the final selection of videos. The measures are rather arbitrary, yet conservative, in order to ensure that the videos appeal to the public due to the relevance of their social identities and not for idiographic reasons, e.g. their personal connection to the person behind the YouTube channel. Lowering the threshold often resulted in sections with only a handful of unique commenters, which negated the necessary conditions of anonymity and deindividuation. Without them, any talk of social identity in non-experimental settings can be on shaky grounds. On the other hand, increasing the threshold would significantly reduce the breadth of videos. Hence, these cut-off points guaranteed a happy medium of 21 videos of Christian–atheist debates and 20 videos of Christian–Muslim debates that met all three criteria.

With rare exceptions, the videos were typically uploaded by third-party YouTube channels from 2008 to 2016. Most of the featured debaters were prominent figures within their respective communities: atheist thinkers such as Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and Christopher Hitchens; Christian theologians and apologists such as Frank Turek and William Lane Craig; and Muslim preachers such as Shabir Ally and Ahmed Deedat. These figures are frequently referenced in the commentary sections of the respective videos. However, it was not uncommon to see references to them in other commentary sections, a fact that hints to the possibility that some of the users were habitual interreligious debaters.

The comments were scraped in January and February of 2017 through YouTube Comment Scraper, a free, online tool. 243,468 comments were returned from the 21 videos of Christian–atheist debates and 84,784 comments from the 20 videos of Christian–Muslim debates. Once collected, they were examined to identify the user’s religious identity.Footnote 1 (Ir)religious identity was coded based on two types of statements: (1) self-identification statements (e.g. “I am a Christian/atheist/Muslim” and its variants) and (2) statements asserting belief in the Christian or Islamic God or disbelief in deities (e.g. “Jesus is my Lord”, “God doesn’t exist”, “Islam is truth,” etc.). This resulted in 52,612 identity-coded comments for the Christian–atheist and 24,179 comments for the Christian–Muslim debates. The remaining comments were excluded from the analyses.

Interrater reliability checks were performed to evaluate the appropriateness and consistency of the coding. 6456 and 4109 comments for each debate, respectively, were randomly selected and distributed in smaller subsets to six different coders. The reliability checks returned matching coding for 99.99% of the Christian–atheist commentsFootnote 2 and 100% of the Christian–Muslim comments.

Analytic Strategy

Topic Models

Topic modeling is a text analysis method of the same logic with content analysis where (large) sets of textual data are coded into “topics” through computer-embedded algorithms (Mohr and Bogdanov 2013). While the researcher determines the number of identified topics, the algorithm assesses their distribution based on probabilistic models or linear algebra (Mohr and Bogdanov 2013; Papadouka, Evangelopoulos, and Ignatow 2016). Topics are made of specific combinations of words; therefore, one’s presence increases the likelihood of their appearance in the document (Mohr and Bogdanov 2013; Papadouka et al. 2016). Although topic extraction can be conducted through several algorithms (for a comprehensive overview, see Aggarwal and Zhai 2012), Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) is preferred here for three main reasons: (1) efficiency in the execution time; (2) reliability of the extraction outcome; and (3) closer semblance to human cognition (Evangelopoulos 2013; Ignatow et al. 2016; Landauer 2013; Papadouka et al. 2016).

LSA acknowledges that meaning is an ongoing construct of human interactions (Evangelopoulos 2013; Landauer 2013). Methodologically, the algorithm follows the principles of factor analysis to uncover the latent dimensions in a body of documents (Landauer et al. 1998). For textual data, the algorithm examines the co-occurrence of words, instead of standardized survey items. Specifically, LSA employs truncated singular value decomposition to build a vector space model (VSM) in the form of a frequency matrix of terms (dimensions) by documents (vectors). Since text data of this sort tend to be voluminous and ‘noisy’, the analytic process entails consecutive steps where words with a shared root and/or meaning are tied and inconsequential terms, such as pronouns and prepositions, are filtered out. Ultimately, the coexistence of meaningful terms in the same ‘bag of words’ determines the factors within the semantic space of principal components (Evangelopoulos 2013; Evangelopoulos et al. 2012; Landauer et al. 1998). Unlike factor analysis, LSA does not offer direct dimensionality measures. To compensate for this shortcoming, Zhu and Ghodsi (2006) developed a change-point of eigenvalues detection test based on log-likelihood ratio estimation to determine the optimal number of factors.

The analysis was pursued through SAS Enterprise Text Miner 14.3 with log-entropy as a weighting method. This scheme separates the wheat from the chaff by assessing the appearance likelihood of terms across the text corpora and assigning greater weight to words that appear more frequently in smaller batches of documents against those who appear more uniformly (Chisholm and Kolda 1999; Landauer et al. 1998). A dictionary of common synonyms was created to assist with meaning consolidation. Upon extraction, the topics were labeled based on high-loading descriptive terms. When straightforward labeling failed, an interpretive examination of the comments complemented the process. Interestingly, there was only one topic per study in which straightforward labels could not be applied, both of similar discussions, i.e. identity statements.

Topic-Sentiment Analysis

Topic sentiment analysis (TSA) is a text analytics technique designed to compute the polarity of emotions across topics in sizable sets of textual data (Ignatow et al. 2016; Lin and He 2009). It combines topic modeling and sentiment analysis (SA), a technique used to examine viewpoints, evaluations, attitudes, and sentiments related to a variety of objects, subjects, and matters (Liu and Zhang 2012). Thus, it allows researchers to obtain fine grained information about controversies, convergences, and divergences.

Here, TSA consists of a multi-stage process starting with topic extraction through LSA and a lexicon-based SA (Liu et al. 2005) performed separately. Each comment is assigned a binary numerical value for each topic (1 = present, 0 = absent) and an overall sentiment score, which later corresponds to a sentiment category (positive, neutral, or negative). The end product takes the form of a correspondence analysis map. Correspondence analysis enables the graphical representation of the relationship between nominal variables on a parameter space of limited dimensionality (Greenacre and Blasius 1994). The analysis is based on a contingency table where the topics are found in rows and the sentiment categories in columns. The Chi square statistic is, then, calculated to assess whether topics and sentiment categories are independent. In this case, the Chi square statistic should resemble a Chi square distribution with (r-1)(c-1) degrees of freedom (Ignatow et al. 2016; Yelland 2010) where r represents the number of (ir)religious groups and c represents the number of sentiment categories. The dimensionality of the plot is identified by the inertia explained by each of the components (Yelland 2010).

Case Study 1: Christian–Muslim Debates

Overview

In the post 9/11 era, international relations resemble more of Huntington’s (1993) dystopian clash of civilization between the (Christian) Western societies and the Muslim World, amounting each other as notable cultural outgroups. Negative attitudes towards Islam have increased (Ogan et al. 2014; Zick et al. 2011) but, most importantly, both Christians and Muslims hold widespread intergroup biases (Henry and Hardin 2006; Hunsberger and Altemeyer 2006; Rowatt et al. 2005; Sterkens and Anthony 2008). Interreligious debates online afford insights on how these groups communicate their biases vis-à-vis one another, making the leap from opinion-based research to behavioral expressions of intergroup relations.

As long-established religious communities, it is reasonable to expect Christian and Muslim identities to inform the topic favorability (H1) and the direction of topic-sentiment polarity (H2A and H2B). Should one also expect stronger patterns for one group or the other? Based on SIT, no. Both memberships are founded upon close-knit communities with explicit cultural boundaries, frequent intra-group interaction, and deeply influential canonical texts. Surely, other parameters ought to be considered. First, notwithstanding the substantive, doctrinal differences, Islam and Christianity proclaim core concepts of universal brotherly love and understanding (see ummah, “Love one another”) that, in principle, would deter their members alike to engage in divisive behavior. Second, in alignment with SIT’s proposition of social identities as a source of self-esteem, research has shown that minorities often maintain positive self-image (Crocker and Major 1989) and seek to battle negative public perceptions (Hornsey 2008). Thus, it becomes likely for them to employ more positive terminology in their narratives. Unfortunately, while one cannot deny elements of majority-minority dynamics here, the data do not afford formally assigning majority-minority status to the groups involved. The reason being that YouTube commenters can—and substantively do—reside in virtually any part of the world, be it Christian-, Muslim-, or secular-majority country. And although it may be hard to assume that the majority of Christian or Muslim participants come from Christian-minority or Muslim-majority countries, respectively, the truth of the matter is that we cannot determine the configuration of the sample and whether the percentage of these users is below the tipping point. Third, studies on metastereotypes and metaprejudice suggest that awareness of what the outgroup believes about the ingroup can pose additional strain on intergroup relations (Putra and Wagner 2017) or, occasionally, can incentivize in-group members to present their best self (Hopkins et al. 2007). Since there is no measure available about metastereotypes and metaprejudice among the participants, their role in the study could only be speculated.

In conclusion, taking all these into account, I have no tangible or explicitly testable theoretical grounds to expect that Christian or Muslim users will drive polarizing discussions more than the other. Thus, it is further hypothesized that:

H3

Christians will tend to exhibit comparable instances of positive in-group and negative out-group bias as Muslims.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

In this study, 850 unique usernames were identified (C = 319 and M = 531). Out of the 24,179 comments they produced cumulatively, 12,729 comments belonged to Christian users (52.6%) and 11,450 comments to Muslim users (47.4%). On average, each user produced 28.41 comments (Mdn = 6, SD = 105.26) with the distribution clearly being positively skewed (skew = 15.41). A single user left the astounding number of 2427 comments. To account for this variation, the topic extraction was repeated without the comments produced by usernames who contributed more than 1000 comments in each case study. The resultsFootnote 3 suggested that despite the prolificity, this user did not inform the content of the topics substantially.

Topic Models

The change-point detection test suggested that the semantic space of Christian–Muslim comments was best represented with 7 factors. As one can see in Table 1, Christian and Muslim commenters are mainly preoccupied with theological matters, which seem to be intertwined with questions of ontology and epistemology. Regarding the ontological facet of the debate, the nature of Jesus constitutes a significant controversy (T06 Jesus’ divinity and T07 Jesus the prophet). Similarly, T01 trinity deals with the nature of God. These factors seem to represent the points of maximal intergroup doctrinal distinction, an attempt for in-group–out-group discrimination. It is worthwhile noting that by discussing God’s or Jesus’ nature, the users do not merely express theological disagreements, but they target at what they see as their feet of clay, respectively. For Muslims, a triune God logically undermines Christianity’s monotheism. “How can a God die?”, they also ask. A human Jesus, a prophet without claims of divinity sticks as a more coherent, thus superior explanation. Christians are on the defense here, and they do so sternly by noting that a complex, beyond the human cognitive faculties explanation of God’s nature is proof of transcendence and not of flaw. The deepening of intergroup boundaries further spills over on how users identify themselves religiously, often in comparative terms (T02 identity statement), where self- and hetero-definitions of each group membership are often blended with stereotyping and altercations.

How do Christians and Muslims know what they know? Religious texts are frequently employed as sources of knowledge and (in)validation. T03 scripture and T04 Islamic scripture reveal the important normative power of sacred documents. Christian and Muslim commenters make references to passages to support their arguments and beliefs but also to challenge the trustworthiness of each other’s religious texts, often suggesting the inferiority of the outgroup. Finally, T05 cross-examination emerges as a typical debating strategy for the extraction of information and clarifications from the other side, the assessment of a claim’s soundness or the exposure of logical fallacies.

It is important to understand that an argumentative process takes place that flows among the subjects of discussion. Upon the outgroup’s unfavorable assessments (e.g. “Remember that the [r]eal God has no partners. If you add partners with Him that means you are polytheists”Footnote 4—T01), the ingroup defends (e.g. “it’s [a] bit hard to understand GOD with our finite brain!”—T01) and deflects to unfavorable assessments of the outgroup (e.g. “[H]ow can you trust Quran verses which Muhammad claimed, [when] Allah could not reveal himself to Muhammad…?”—T04) and outright intergroup derogation (e.g. “…[I] got the impression that our Muslim friends believe that Christianity is a ‘FALSE’ RELIGION, because we as Christians won’t let MUSLIM TERRORISTS murder us…”, “…we Muslims [are] the biggest religion in the world… if we are aggressive we can kill all Christian… but we will not [do] it [because] we Muslims mean peace, not like your religion killing and [being] racist”—T02).Footnote 5

Turning to hypothesis H1, it is expected that each religious group will be associated with factors reflecting normative elements of their faith. For instance, T01 trinity, T03 scripture, and T06 Jesus’ divinity would be more likely to emerge from the comments of Christian users, while T04 Islamic scripture and T07 Jesus the prophet in Muslims’.

The results of the Chi square analysis of independence presented in Table 2 above suggest that users tend to adhere to discursive elements of faith that shape their perceptions of belonging. Indeed, T01 trinity and T06 Jesus’ divinity are more associated with Christian than Muslim users, and vice versa for T07 Jesus the prophet. In contrast, T03 scripture and T04 Islamic scripture contradict the prediction with Muslim users relying more heavily on a broader sample of scriptural documents, whereas the latter being associated with Christian users, who identify it as the soft spot of the Islamic tradition and attack it as unreliable, violence-inducing, and repressive. When it comes to T02, Muslim commenters are more inclined to engage in identity statements in what appears to be an attempt to self-definition, defense of their tradition, and correction of negative images.

Topic-Sentiment Analysis

Topic-sentiment polarization is hypothesized to occur as Muslim and Christian users are more likely to use positively or negatively charged language for factors depending whether they are linked to their ingroup identity (H2A) or the outgroup (H2B), respectively. Once again, the results are rather in line with the predictions. Muslims appear to use more positive terms compared to Christians for T04 Islamic scripture, T07 Jesus as prophet, and T02 identity statement while Christians use more negative terminology in comparison to Muslims for the same factors (see Table 3). The pattern is reversed for T06 Jesus’ divinity, a Christian identity-specific factor.

Not surprisingly, due to overlapping religious elements, Christian and Muslim users do not exhibit statistically significant topic-sentiment polarity for T01 trinity (p = 0.249). Christians tend to use slightly more negative words than Muslims for T03 scripture, possibly because some of these religious texts (see Quran, Surah, etc.) are not revered in the Christian tradition, which allows more space for dismissive language. Christian commenters are also more inclined to use negative terminology than Muslims for T05 cross-examination.

Clearly, polarization exists among Christian and Muslim YouTube commenters. But how deep is the rift and which factors drive the way? The polarity index (PI) offers more straightforward answers. The index is based upon the premises of Chi square analysis for independence and accounts only for positive and negative sentiment values. As shown in Table 4, T04 Islamic scripture has by far the highest polarization score, followed by T06 Jesus’ divinity. For the other factors, the polarization is modest at best, while, when neutral scores are removed from the equation, T03 scripture appears to bear non-significant differences in sentiment among Christians and Muslims.

Correspondence Analysis

Correspondence analysis indicates a statistically significant topic-sentiment dependency for Christian (χ2 = 445.394, p < 0.001) and Muslim (χ2 = 415.791, p < 0.001) commenters. In Table 5, the Chi square statistic and model diagnostics suggest that the fit is good with the model explaining 3.77% of the variation. The first components used for the two-dimensional display denote 86.06% of the variation. Component 1, plotted in the x-axis, represents sentiment moving from positive (left) to negative (right), while component 2, plotted in the y-axis, represents factor preference by Muslims on the bottom quadrants and Christians on the top quadrants. Capturing 60.52% of the inertia, sentiment appears to be a more reliable predictor of topic-sentiment polarization for Christian and Muslim commenters, essentially meaning that Christians and Muslims do not differ as much on what they discuss but on how they discuss it.

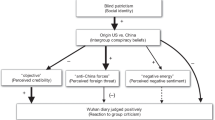

The Christian domain (QI, QII) features what can be described as otherworldly factors, ontological in nature, whereas the Muslim domain (QIII, QIV) feature this-worldly factors, of human nature (e.g. Jesus as Prophet), affairs, or creation (e.g. scripture). Interestingly, T06 Jesus’ divinity demonstrates a high association with negative sentiment (Fig. 1), partly due to the negative terms that compose the topic (see the descriptive terms “sin”, “die”, “kill” in Table 1). This could explain the unexpectedly high occurrence of negative terms among Christian users who emphasize the self-sacrifice of their religious leader for the greater good. That is, in this context, words commonly understood as negative bear positive evaluative connotations.

Discussion

The present case study sought to examine the content and level of intergroup topic-sentiment polarization among Christian and Muslim YouTube commenters. With reference to the content, the factors appeared theoretically and intuitively related to core elements of the Christian and Muslim religious traditions. Furthermore, Christian and Muslim users were found to favor predominantly factors conceptually linked with their respective religions (H1) and discuss the factors favorably (H2A) or unfavorably (H2B) depending on whether they represent their own or the outgroup’s identity, respectively. Regarding hypothesis H3, the results offer mixed support of comparable intergroup bias for Christian and Muslim users. On one hand, Christian and Muslim users exhibit the exact same instances of topic favorability. On the other hand, in terms of topic-sentiment polarization, out of the 6 topics that exhibited sentiment polarity, Christians tended to use more positive terms than Muslims in only one of them (T06 Jesus’ divinity), while they were more likely to use negative terms in comparison to Muslims for the remaining five.

The results also showed that it was not rare for commenters to fixate on subjects of discussion that were not specific to their in-group identity. For example, Christians picked on Islamic scripture more than Muslims and Muslims discussed about trinity almost as much as Christians. This is not an intuitive finding if we solely expect topic engagement based on in-group favoritism. Why would this happen? It is important to note that the discussants can choose from a large repertoire of religious arguments, concepts, and narratives. According to SIT, individuals engage in the sort of comparisons that are advantageous for their group (Hogg et al. 1995). So, when Christians interpret the Quran as a promoter of violence and oppression or when Muslims question the rational foundation of the Christian concept of God, they strategically seek to establish the type of unfavorable assessments, which would increase the feelings of ingroup superiority (Brown 2000; Hogg and Terry 2000; Hornsey 2008). In the words of a commenter, “[H]ey your religion is not the truth. [M]ine is the truth….” The battle of superiority has a clear goal: the (absolute) source of moral authority.

Case Study 2: Christian–Atheist Debates

Overview

Christians and atheists represent different forms of identity and hold antithetical views about God’s existence. Religious groups maintain a distinct sense of belonging and cohesive worldviews (Kinnvall 2004; Ysseldyk et al. 2010) regularized and legitimized through the normativeness of a divine power (Hogg et al. 2010; Hunsberger and Jackson 2005; Silberman 2005). In contrast, atheists are only recently characterized as a community on the making (Catto and Eccles 2013; Cimino and Smith 2011; Smith 2013). While previous research points to some emerging elements of the atheist identity, such as the value of reason, science, and empiricism (Caldwell-Harris et al. 2011; LeDrew 2013; Williamson and Yancey 2013; Zuckerman 2015), atheists remain largely isolated and loose as a social category (Cimino and Smith 2011).

As already mentioned, research on the ‘minimal group paradigm’ and beyond (see Hunsberger and Altemeyer 2006) offers grounds to expect that atheists will exhibit intergroup biases in the form of topic favorability (H1) and topic sentiment polarization (H2A and H2B). However, it is questionable whether their narratives will reflect this to a comparable extent to Christian users, or more. There are two main reasons for this, directly or indirectly linked to their recent social membership: the lack of authoritative texts, symbols, ritualistic practices, and common history (Werczberger and Azulay 2011) and regular intra-group interaction that aid the development of group norms (Moor and Kanji 2019; Smith and Postmes 2009). It follows that:

H4

Atheists will tend to exhibit fewer instances of in-group and out-group bias than Christians.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

52,607 comments were entered in the analysis, produced by 2834 unique usernames (C = 1391 and A = 1443). The comments by username ranged from 1 to 1820 (M = 18.56, Mdn = 3, SD = 70.37, skew = 14.75) with a few users leaving more than 1000 comments.Footnote 6 Nevertheless, the number of comments by social identity is almost evenly distributed with 26,670 comments made by Christian users (50.7%) and 25,937 comments by atheist users (49.3%).

Topic Models

The change point detection test indicated that the semantic space of Christian and atheist comments was best represented by the extraction of 10 factors (Table 6). Once again, the commenters are preoccupied with the ontological question. Through discussions of T02 Jesus the savior, T03 identity statement, T05 morality, T06 belief, and T10 truth claims, users argue about the nature of entities and the essence of abstract objects and subjects, while negotiating what is and what is not. T10 truth claims can be described as the fundamentalist topic due to the users’ insistence that they are the ones holding the (one and only) truth (e.g. “Is what you say true? What is truth? Without God you only have your opinion.”, “I can prove evolution is true, you can’t prove [G]od is true”). Atheist and Christian users also engage in epistemological arguments to explain how they know what they know and which method of knowing is more reliable. T01 burden of proof, T09 creation (e.g. “What do you think created the Big Bang? Why not [G]od? Where did the particles that caused the Big Bang come from?”), T08 Bible, and T04 scientific theories (e.g. “No, it’s NOT still a theory. The Big Bang HAPPENED. It’s [a] FACT, just like evolution is no longer a theory. It’s [a] FACT”) represent such reasoning. Afresh, the discussions for each factor is not isolated and independent of the rest. Instead, a dialectic takes place indicating an inner line of reasoning and a process of attack, defense, and deflection.

Next, a Chi square analysis of independence was performed to test H1. Based on common knowledge and/or empirical findings, factors such as T02 Jesus the savior, T05 morality, T08 Bible, T09 creation, and T10 truth claims would be expected to be more prevalent among Christian than atheist users, and vice versa for T04 scientific theories.

As Table 7 shows, the results suggest only partial support. Christian users are indeed more likely to discuss topics T02 Jesus the savior, T05 morality, T08 Bible, T09 creation, T10 truth claims in comparison to atheist users. Yet, atheists tend to be associated with T04 scientific theories as much as Christians (p = 0.261). Only T01 burden of proof exhibits higher occurrence among atheist users who seem to use this argument as their thesis statement in the debate. In general, the pattern suggests that for not Christian identity-specific factors, the participation in their discussion is rather split among Christian and atheist commenters.

Topic-Sentiment Analysis

The topic-sentiment analysis was performed to assess whether Christian and atheist YouTube commenters’ polarization emerges as a function of identity-specific intergroup biases (H2A and H2B). The results in Table 8 indicate that polarization clearly exists but, unlike the nuanced predictions, it appears that Christians tend to use more positive terms across all factors, while atheist users are inclined to employ a rather negative terminology. The only aberration in the pattern is T04 scientific theories since positive and negative usage does not vary for Christians and atheists (p = 0.106). Science as a topic of discussion is approached intellectually and, therefore, elicits smaller sentiment variation. At the same time, the prevalence of positive emotional terms by Christians and atheists indicates that Christian users do not treat science and religion as necessarily antagonistic entities negating atheists’ attempt to appropriate the value of science as a distinctive characteristic of their identity. Coupling this finding with T09 creation, it becomes apparent that creationism and intelligent design not only meet their purpose to provide Christians with plausible constructs to counter well-known scientific theories (see evolution and the big bang), but also conciliate religion and science in a way that the latter can be integrated to their Christian identity.

The topic-sentiment polarization between Christian and atheist commenters seems to be mainly informed from each group’s relationship with religion. Christians affirm faith whereas atheists negate it, thus using more positive and negative terms respectively. While this fundamental difference blurs the expression of intergroup bias, one can notice that three out of the four most polarizing factors (Table 9), namely T09 creation, T02 Jesus the savior, and T08 Bible, are identity-specific topics of the Christian faith. This suggests that the intergroup polarization is not singularly driven by the positive–negative nature of their beliefs but also by context-specific intergroup dynamics. It also becomes apparent that, by comparison, symbols of the Christian faith are more polarizing in the Christian–atheist debates than the Christian–Muslim debates.

Turning to H4, atheists were expected to be associated with fewer instances of intergroup bias than Christians. Once again, the results offer only partial support. Indeed, atheists exhibit no instances of positive in-group bias, but considerably more negative bias compared to Christians. It can be argued that, in this stage of identity development, atheist users find it easier to define themselves as what they are not than what they are.

Correspondence Analysis

A topic-sentiment map (Fig. 2) was produced based on a topic-by-sentiment contingency table of the data from the Christian-atheist commentaries and the subsequent Chi square distances. The graph is plotted symmetrically and the distances among topics and sentiment levels indicate the degree of their association.

The results affirm the topic-sentiment dependency for Christian (χ2 = 877.388, p < 0.001) and atheist (χ2 = 1065.585, p < 0.001) commenters. Table 10 shows that component 1, topic preference, drives the association capturing 75.84% of the variation. Note that, between the two components, sentiment was more reliable predictor for Christian–Muslim debates. The first component, plotted along the x-axis, represents the factor favorability by Christian (left) and atheist (right) users. Similarly, the second component, plotted along the y-axis, represents sentiment flows from negative (QIII, QIV) to neutral/positive (QI, QII).

A close examination of the map suggests that quadrant II constitutes the space of Christian in-group favorability: factors predominantly discussed by Christian users in positive terms (Christian values). Similarly, quadrant I represents the space of atheist in-group topic-sentiment favorability (atheist values). Left and right quadrants seem to exemplify the classic distinction between the sacred and the mundane. Quadrant IV represents the factors associated with negative terminology by atheists. Unsurprisingly, factors such as T06 belief and T03 identity statement land here. Both reflect the rejective way atheist users define themselves against God, religion, and Christians, a negation of theism. Lastly, quadrant III reflects the factor that Christians define negatively. Why would Christians attribute negative connotations to morality? It appears that they emphasize the constraining qualities of God-driven morality in their commentaries: morality is framed as a force that prevents someone from wrongdoing (e.g. “If morals are subjective, murder would be neither moral [n]or immoral”) rather than endorsing benevolent acts, as possible positive language would indicate.

Discussion

The present case study sought to examine the content and level of intergroup topic-sentiment polarization among Christian and atheist YouTube users. While SIT accurately predicts the topic preferences of Christian users (H1), it seems harder to do so for atheist users. This can be happening due to several reasons. First, although atheism is not a new walk of life, it has been largely construed as an individual instead of social identity. The sense of groupness and intra-group interactions that are required to forge social belonging are a recent advent (Cimino and Smith 2011, 2014; Smith 2013). Therefore, the establishment of collective norms regarding the group’s beliefs, attitudes, and narratives does not seem complete yet. Second, atheists often report to value individuality and independence of thought (Hunsberger and Altemeyer 2006; Smith 2013) which may deter them from aligning with any popular rhetoric. Note, however, that these values are not necessarily antithetical to the expression of normative behavior. Indeed, some constituents of individualism have been found to be normative (Dubois and Beauvois 2005). A case in point is atheists’ approach to morality (e.g. “We don’t need [G]od to be able to understand what is right or wrong”), which predominantly invokes the norm of internality. Third, despite evidence suggesting otherwise for members of atheist organizations (see Smith 2013), it may still be the case that, for a number of atheists, atheism is organized around unbelief in God and the rejection of religion.

The latter point can be further corroborated by the consistent negative linguistic bias that atheists express on almost any topic of discussion, and particularly the ones associated with doctrinal elements of Christianity. Of course, we need to keep in mind that the data used here are the product of unstructured religious discussions. That is, the “us” versus “them” priming of the videos and the subsequent commentaries on religion and God can generally compel atheists to activate those aspects of their identity that reflect their relationship to these subjects attributing secondary pertinence to other, more positive elements of their identity.

General Discussion

Fifty years after the internet’s birth, the explosion of social media data is not met with nearly the same enthusiasm among scholars of religion. Drawing from social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner 1979), a well-known explanatory framework for intergroup phenomena, this paper aspired to shed light on the under-researched subject of online interreligious communications and polarization. Based on the anonymity and impersonality of microblogging platforms, such as YouTube, which provide fertile ground for individuals to deindividualize and behave based on their social identities, I argued that interreligious communications will tend to rely on normative elements of group identity and normative emotional responses to in-group and outgroup identity-specific themes.

In sum, the results for the two sets of interreligious debates suggest that the interreligious discussions center around remarkably consistent identity-specific topics and topic-sentiment polarization takes place along (ir)religious lines. These findings are not so intuitive if we account for the medium that they take place. Research on online debates showcases that users soon deviate from the original topic of debate to more ‘newsworthy’ or current event-driven subjects (Yardi and Boyd 2010). With the attention fixed on ‘big picture’ religious questions, such deviations are probably too minute to form coherent factors here. Moreover, scholars have found that, while present, social and political polarization may not be as widespread as often expected (Baldassarri and Bearman 2007; Ignatow et al. 2016), a contrast that highlights the deep consequentiality of our social identification vis-à-vis God for intergroup relations and the usefulness of online, interactional data to uncover it.

Notwithstanding the inter-case commonalities, the polarization among Muslim and Christian users stands on the emotional value (ethos) they assign to theological concepts and figures of their Abrahamic tradition(s), whilst the Christian–atheist divide is a matter of the cognitive frameworks they approach questions of meaning (worldview). Moreover, the polarization is more pronounced between Christian and atheist users than Christian and Muslims. Combined with the greater general engagement (243,468 vs 84,784 comments), it supports the view that secularism may be turning to a strong contender of Christianity on the battle of moral authority (Kettell 2009). Last, the atheist identity appears almost abnormative in terms of master narratives and deeply normative in conducing intergroup polarization. Mind that explicit social categorizations suffice to generate intergroup biases (Hewstone et al. 1981; Tajfel et al. 1971), but in-group norms and narratives are the product of an iterative, long-term process (van Kleef et al. 2019; Peek 2005), yet incomplete within the newly-emergent atheist community.

All in all, this paper offers important support for the potential of topic-sentiment analysis as a statistical method. The consistency and strength of the reported patterns and their conceptual relevance to the propositions of social identity theory (SIT) suggest that topic-sentiment analysis can be added to the toolkits of social researchers who wish to take advantage of big data techniques and user-generated content. It also showcases the possibilities offered by computer-mediated communications for the examination of religious phenomena beyond the bounds of geography or membership. This comes at a methodological and inferential cost: we are often unable to identify, thus, to qualify based on geography, demographics, or denomination. Other limitations do exist and need to be addressed. Topic modeling and sentiment analysis do not account for the contextual use of words. For this reason, a more in-depth examination of the relevant comments has often complemented the analysis to help guide the interpretation of the topics.

Conclusions and Implications

In the beginning of this paper, I took issue with two paradoxes. First, despite the unique normative yield of religion in people’s lives (Hogg et al. 2010; Hunsberger and Jackson 2005; Silberman 2005) and its role in intergroup bias (Bain et al. 2013; Eisinga et al. 1995; Laythe et al. 2002), social identity research has largely neglected religious membership, or its negation, as a social identity. Here, I showcased how YouTube interreligious debates serve to uplift and defend the in-group (Hopkins et al. 2007; Hornsey 2008) and to delegitimize the outgroup in a broader battle for moral authority (Kettell 2009; Sumerau and Cragun 2016). Second, social identity and religion scholars lack enough engagement with real-world intergroup interactions. Part of this omission is justified by the historical challenges in observing group interactions in a systematic way often resorting in self-reports or ethnographic accounts of such interactions. Yet, nowadays, online spaces offer a multitude of opportunities to gain access to this coveted aspect of social life. While this research generally aligns with survey- or interview-based findings on Christians, Muslims, and atheists, as well as attitudes towards them (Bain et al. 2013; Cimino and Smith 2011; Edgell et al. 2016; Henry and Hardin 2006; Hunsberger and Altemeyer 2006; Rowatt et al. 2005; Sterkens and Anthony 2008; Sumerau and Cragun 2016; Williamson and Yancey 2013), there is a notable discrepancy: the topics clearly show a struggle on who explains the world best, who holds the truth, instead of issue-based social divisions and cultural incompatibilities. Stereotyping and cultural altercations are not absent, as the sample comments revealed, but such elements fail to form substantive, major topics indicating that they function mostly as a reaction to challenged identity characteristics. In light of this finding, it may well be that issue-based social differences and cultural incompatibilities, often emphasized in the literature, are evoked as rationalizations, not the reasons, of interreligious prejudice ensuing from an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality (Hartley 1946).

We live in a world of tensions. This paper showed how online environments, such as YouTube, become spaces of strenuous interreligious encounters. With scholars noting the interconnectedness and complementarity of online and offline religious activities (Campbell 2012; Helland 2005) and the role of negative intergroup contact in accentuating prejudice (Dixon et al. 2010), future research ought to examine how online religious encounters shape offline intergroup attitudes and courses of behavior. Last, for religious practitioners, especially those interested in promoting interreligious dialogue, the grim shadow of interreligious polarization—that this study paints—comes with a crack from which light gets in: for Christians and Muslims, reverence of shared theology; for Christian and atheists, to the surprise of all, science. Upon this thin strip of common ground, bridges can be built.

Notes

YouTube does not have a unique username policy. Alphanumeric and uncommon aliases provided a fair estimate of uniqueness. When common usernames appeared, additional criteria, e.g. (1) corresponding video ID, (2) chronological association of comments, (3) co-appearance in exchanges with similar users, and/or (4) consistency in content and arguments, were used to attribute comments to users.

Second round. First round matching was 99.97%.

Available upon request.

The quotes are often edited for clarity.

These examples are provided for illustrative purposes. This is not meant to be read that the flow of arguments is unidirectional or singular.

The topic extraction was repeated without the top commenters. The factors’ content did not differ substantially. Available upon request.

References

Abisheva, Adiya, Venkata Rama Kiran Garimella, David Garcia, and Ingmar Weber. 2014. Who Watches (and Shares) What on Youtube? And When?: Using Twitter to Understand Youtube Viewership. in Proceedings of the 7th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, 593–602. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press.

Aggarwal, Charu C., and ChengXiang Zhai (eds.). 2012. Mining Text Data. Boston, MA: Springer.

Anderson, Jon W. 2003. The Internet and Islam’s New Interpreters. In New Media in the Muslim World: The Emerging Public Sphere, ed. D.F. Eickelman and J.W. Anderson, 41–55. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Bain, Paul G., Matthew J. Hornsey, Renata Bongiorno, Yoshihisa Kashima, and Daniel Crimston. 2013. Collective Futures: How Projections About the Future of Society are Related to Actions and Attitudes Supporting Social Change. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 39(4): 523–539.

Baldassarri, Delia, and Peter Bearman. 2007. Dynamics of Political Polarization. American Sociological Review 72(5): 784–811.

Bessi, Alessandro, Fabiana Zollo, Michela Del Vicario, Michelangelo Puliga, Antonio Scala, Guido Caldarelli, Brian Uzzi, and Walter Quattrociocchi. 2016. Users Polarization on Facebook and Youtube. PLoS ONE 11(8): e0159641.

Blitvich, Pilar Garcés-Conejos. 2010. The YouTubification of Politics, Impoliteness and Polarization. In Handbook of Research on Discourse Behavior and Digital Communication: Language Structures and Social Interaction, ed. R. Taiwo, 540–563. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Bond, Rod. 2005. Group Size and Conformity. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 8(4): 331–354.

Brown, Rupert. 2000. Social Identity Theory: Past Achievements, Current Problems and Future Challenges. European Journal of Social Psychology 30(6): 745–778.

Burgess, Jean, and Joshua Green. 2018. Youtube: Online Video and Participatory Culture, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Polity.

Caldwell-Harris, Catherine L., Angela L. Wilson, Elizabeth LoTempio, and Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi. 2011. Exploring the Atheist Personality: Well-Being, Awe, and Magical Thinking in Atheists, Buddhists, and Christians. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 14(7): 659–672.

Campbell, Heidi A. 2005. Making Space for Religion in Internet Studies. The Information Society 21: 309–315.

Campbell, Heidi A. 2010. Religious Authority and the Blogosphere. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 15(2): 251–276.

Campbell, Heidi A. 2012. Understanding the Relationship Between Religion Online and Offline in a Networked Society. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 80(1): 64–93.

Campbell, Heidi A. 2013. Religion and the Internet: A Microcosm for Studying Internet Trends and Implications. New Media & Society 15(5): 680–694.

Catto, Rebecca, and Janet Eccles. 2013. (Dis)Believing and Belonging: Investigating the Narratives of Young British Atheists. Temenos—Nordic Journal of Comparative Religion 49(1): 37–63.

Cheong, Pauline Hope, Alexander Halavais, and Kyounghee Kwon. 2008. The Chronicles of Me: Understanding Blogging as a Religious Practice. Journal of Media and Religion 7(3): 107–131.

Cheong, Pauline Hope, and Jessie P.H. Poon. 2009. Weaving Webs of Faith: Examining Internet Use and Religious Communication Among Chinese Protestant Transmigrants. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 2(3): 189–207.

Cheong, Pauline Hope, Jessie P.H. Poon, Shirlena Huang, and Irene Casas. 2009. The Internet Highway and Religious Communities: Mapping and Contesting Spaces in Religion-Online. The Information Society 25(5): 291–302.

Chisholm, E., and T. G. Kolda. 1999. New Term Weighting Formulas for the Vector Space Method in Information Retrieval. ORNL/TM-13756, 5698.

Cimino, Richard P., and Christopher Smith. 2011. The New Atheism and the Formation of the Imagined Secularist Community. Journal of Media and Religion 10(1): 24–38.

Cimino, Richard P., and Christopher Smith. 2014. Atheist Awakening: Secular Activism and Community in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Crocker, Jennifer, and Brenda Major. 1989. Social Stigma and Self-Esteem: The Self-Protective Properties of Stigma. Psychological Review 96(4): 608–630.

Dawson, Lorne L., and Douglas E. Cowan. 2013. Religion Online: Finding Faith on the Internet. Florence: Taylor and Francis.

Dixon, John, Kevin Durrheim, Colin Tredoux, Linda Tropp, Beverley Clack, and Liberty Eaton. 2010. A Paradox of Integration? Interracial Contact, Prejudice Reduction, and Perceptions of Racial Discrimination: A Paradox of Integration. Journal of Social Issues 66(2): 401–416.

Dubois, Nicole, and Jean-Léon Beauvois. 2005. Normativeness and Individualism. European Journal of Social Psychology 35(1): 123–146.

Edgell, Penny, Douglas Hartmann, Evan Stewart, and Joseph Gerteis. 2016. Atheists and Other Cultural Outsiders: Moral Boundaries and the Non-religious in the United States. Social Forces 95(2): 607–638.

Eisinga, Rob, Ruben Konig, and Peer Scheepers. 1995. Orthodox Religious Beliefs and Anti-Semitism: A Replication of Glock and Stark in the Netherlands. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34(2): 214–223.

Evangelopoulos, Nicholas E. 2013. Latent Semantic Analysis. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 4(6): 683–692.

Evangelopoulos, Nicholas, Xiaoni Zhang, and Victor R. Prybutok. 2012. Latent Semantic Analysis: Five Methodological Recommendations. European Journal of Information Systems 21(1): 70–86.

Fiske, Susan, and Shelley E. Taylor. 2013. Social Cognition: From Brains to Culture, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Greenacre, Michael J., and Jörg Blasius. 1994. Correspondence Analysis in the Social Sciences: Recent Developments and Applications. London: Academic Press.

Greene, Steven. 2004. Social Identity Theory and Party Identification. Social Science Quarterly 85(1): 136–153.

Hartley, Eugene L. 1946. Problems in Prejudice. Oxford: King’S Crown Press.

Helland, Christopher. 2005. Online Religion as Lived Religion. Methodological Issues in the Study of Religious Participation on the Internet. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet.

Henry, P.J., and Curtis D. Hardin. 2006. The Contact Hypothesis Revisited: Status Bias in the Reduction of Implicit Prejudice in the United States and Lebanon. Psychological Science (0956-7976) 17(10): 862–868.

Hewstone, Miles, Frank Fincham, and Jos Jaspars. 1981. Social Categorization and Similarity in Intergroup Behaviour: A Replication with ‘Penalties’. European Journal of Social Psychology 11(1): 101–107.

Hogg, Michael A., Janice R. Adelman, and Robert D. Blagg. 2010. Religion in the Face of Uncertainty: An Uncertainty-Identity Theory Account of Religiousness. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14(1): 72–83.

Hogg, Michael A., and Deborah J. Terry. 2000. Social Identity and Self-Categorization Processes in Organizational Contexts. The Academy of Management Review 25(1): 121.

Hogg, Michael A., Deborah J. Terry, and Katherine M. White. 1995. A Tale of Two Theories: A Critical Comparison of Identity Theory with Social Identity Theory. Social Psychology Quarterly 58(4): 255.

Hopkins, Nick, Steve Reicher, Kate Harrison, Clare Cassidy, Rebecca Bull, and Mark Levine. 2007. Helping to Improve the Group Stereotype: On the Strategic Dimension of Prosocial Behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 33(6): 776–788.

Hornsey, Matthew J. 2008. Social Identity Theory and Self-Categorization Theory: A Historical Review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2(1): 204–222.

Hunsberger, Bruce, and Bob Altemeyer. 2006. Atheists: A Groundbreaking Study of America’s Nonbelievers. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Hunsberger, Bruce, and Lynne M. Jackson. 2005. Religion, Meaning, and Prejudice. Journal of Social Issues 61(4): 807–826.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1993. The Clash of Civilizations? Foreign Affairs 72(3): 22.

Ignatow, Gabe, Nicholas Evangelopoulos, and Konstantinos Zougris. 2016. Sentiment Analysis of Polarizing Topics in Social Media: News Site Readers’ Comments on the Trayvon Martin Controversy. Communication and Information Technologies Annual (Studies in Media and Communications) 11: 259–284.

Kettell, Steve. 2009. On the Public Discourse of Religion: An Analysis of Christianity in the United Kingdom. Politics and Religion 2: 420–443.

Kinnvall, Catarina. 2004. Globalization and Religious Nationalism: Self, Identity, and the Search for Ontological Security. Political Psychology 25(5): 741–767.

Landauer, Thomas K. 2013. LSA as a Theory of Meaning. In Handbook of Latent Semantic Analysis, ed. T.K. Landauer, D.S. McNamara, S. Dennis, and W. Kintsch, 15–46. Hove: Psychology Press.

Landauer, Thomas K., Peter W. Foltz, and Darrell Laham. 1998. An Introduction to Latent Semantic Analysis. Discourse Processes 25(2–3): 259–284.

Laythe, Brian, Deborah G. Finkel, Robert G. Bringle, and Lee A. Kirkpatrick. 2002. Religious Fundamentalism as a Predictor of Prejudice: A Two-Component Model. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41(4): 623–635.

Lea, Martin, and Russell Spears. 1991. Computer-Mediated Communication, de-Individuation and Group Decision-Making. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies 34(2): 283–301.

Lea, Martin, Russell Spears, and Daphne de Groot. 2001. Knowing Me, Knowing You: Anonymity Effects on Social Identity Processes within Groups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 27(5): 526–537.

LeDrew, Stephen. 2013. Discovering Atheism: Heterogeneity in Trajectories to Atheist Identity and Activism. Sociology of Religion 74(4): 431–453.

Lin, Chenghua, and Yulan He. 2009. Joint Sentiment/Topic Model for Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, CIKM’09. 375–384. New York, NY, USA: ACM.

Liu, Bing, Minqing Hu, and Junsheng Cheng. 2005. Opinion Observer: Analyzing and Comparing Opinions on the Web. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on World Wide Web, WWW’05, 342–351. New York, NY, USA: ACM.

Liu, Bing, and Lei Zhang. 2012. A Survey of Opinion Mining and Sentiment Analysis. In Mining Text Data, edited by C. C. Aggarwal and C. Zhai, 415–463. Boston, MA: Springer US.

Lövheim, Mia. 2013. Young People, Religious Identity, and the Internet. In Religion Online: Finding Faith on the Internet, ed. L.L. Dawson and D.E. Cowan, 67–82. Florence: Taylor and Francis.

Mohr, John W., and Petko Bogdanov. 2013. Introduction—Topic Models: What They are and Why They Matter. Poetics 41(6): 545–569.

Moor, Liz, and Shireen Kanji. 2019. Money and Relationships Online: Communication and Norm Formation in Women’s Discussions of Couple Resource Allocation. British Journal of Sociology 70(3): 948–968.

Neuberg, Steven L., Carolyn M. Warner, Stephen A. Mistler, Anna Berlin, Eric D. Hill, Jordan D. Johnson, Gabrielle Filip-Crawford, Roger E. Millsap, George Thomas, Michael Winkelman, Benjamin J. Broome, Thomas J. Taylor, and Juliane Schober. 2014. Religion and Intergroup Conflict: Findings From the Global Group Relations Project. Psychological Science 25(1): 198–206.

Ogan, Christine, Lars Willnat, Rosemary Pennington, and Manaf Bashir. 2014. The Rise of Anti-Muslim Prejudice: Media and Islamophobia in Europe and the United States. International Communication Gazette 76(1): 27–46.

Papadouka, Maria Eirini, Nicholas Evangelopoulos, and Gabe Ignatow. 2016. Agenda Setting and Active Audiences in Online Coverage of Human Trafficking. Information, Communication & Society 19(5): 655–672.

Peek, Lori. 2005. Becoming Muslim: The Development of a Religious Identity. Sociology of Religion 66(3): 215–242.

Postmes, Tom, Russell Spears, and Martin Lea. 1998. Breaching or Building Social Boundaries?: SIDE-Effects of Computer-Mediated Communication. Communication Research 25(6): 689–715.

Putra, Idhamsyah Eka, and Wolfgang Wagner. 2017. Prejudice in Interreligious Context: The Role of Metaprejudice and Majority-Minority Status. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 27(3): 226–239.

Rabbie, Jacob M., Jan C. Schot, and Lieuwe Visser. 1989. Social Identity Theory: A Conceptual and Empirical Critique from the Perspective of a Behavioural Interaction Model. European Journal of Social Psychology 19(3): 171–202.

Reicher, S., R.M. Levine, and E. Gordijn. 1998. More on Deindividuation, Power Relations between Groups and the Expression of Social Identity: Three Studies on the Effects of Visibility to the in-Group. British Journal of Social Psychology 37(1): 15–40.

Rowatt, Wade C., Lewis M. Franklin, and Marla Cotton. 2005. Patterns and Personality Correlates of Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Toward Christians and Muslims. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 44(1): 29–43.

Shadid, Wasif, and Pieter S. van Koningsveld. 2001. The Negative Image of Islam and Muslims in the West: Causes and Solutions. In Religious Freedom and the Neutrality of the State: The Position of Islam in the European Union, ed. W. Shadid and P.S. van Koningsveld, 174–195. Leuven/Sterling, VA: Peeters.

Silberman, Israela. 2005. Religion as a Meaning System: Implications for the New Millennium. Journal of Social Issues 61(4): 641–663.

Smith, Jesse M. 2013. Creating a Godless Community: The Collective Identity Work of Contemporary American Atheists. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52(1): 80–99.

Smith, Laura G.E., and Tom Postmes. 2009. Intra-group Interaction and the Development of Norms Which Promote Inter-group Hostility. European Journal of Social Psychology 39(1): 130–144.

Spears, Russell, and Martin Lea. 1994. Panacea or Panopticon?: The Hidden Power in Computer-Mediated Communication. Communication Research 21(4): 427–459.

Sterkens, Carl, and Francis-Vincent Anthony. 2008. A Comparative Study of Religiocentrism Among Christian, Muslim and Hindu Students in Tamil Nadu, India. Journal of Empirical Theology 21(1): 32–67.

Sumerau, J.E., and Ryan T. Cragun. 2016. ‘I Think Some People Need Religion’: The Social Construction of Nonreligious Moral Identities. Sociology of Religion 77(4): 386–407.

Tajfel, Henri. 1979. Individuals and Groups in Social Psychology. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 18(2): 183–190.

Tajfel, Henri, M.G. Billig, R.P. Bundy, and Claude Flament. 1971. Social Categorization and Intergroup Behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology 1(2): 149–178.

Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 1979. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, ed. S. Worchel and W.G. Austin, 33–47. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Turner, John C. 1975. Social Comparison and Social Identity: Some Prospects for Intergroup Behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology 5(1): 1–34.

Turner, John C., Michael A. Hogg, Penelope J. Oakes, Stephen D. Reicher, and Margaret S. Wetherell. 1987. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

van Kleef, Gerben A., Michele J. Gelfand, and Jolanda Jetten. 2019. The Dynamic Nature of Social Norms: New Perspectives on Norm Development, Impact, Violation, and Enforcement. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 84: 103814.

Werczberger, Rachel, and Na’ama Azulay. 2011. The Jewish Renewal Movement in Israeli Secular Society. Contemporary Jewry 31(2): 107–128.

Williamson, David, and George A. Yancey. 2013. There is No God: Atheists in America. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.

Yardi, Sarita, and Danah Boyd. 2010. Dynamic Debates: An Analysis of Group Polarization Over Time on Twitter. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 30(5): 316–327.

Yelland, Phillip. 2010. An Introduction to Correspondence Analysis. The Mathematica Journal 12(4): 86–109.

Ysseldyk, Renate, Kimberly Matheson, and Hymie Anisman. 2010. Religiosity as Identity: Toward an Understanding of Religion From a Social Identity Perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14(1): 60–71.

Yuki, Masaki. 2003. Intergroup Comparison versus Intragroup Relationships: A Cross-Cultural Examination of Social Identity Theory in North American and East Asian Cultural Contexts. Social Psychology Quarterly 66(2): 166.

Zhu, Mu, and Ali Ghodsi. 2006. Automatic Dimensionality Selection from the Scree Plot via the Use of Profile Likelihood. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 51(2): 918–930.

Zick, Andreas, Beate Küpper, and Andreas Hövermann. 2011. Intolerance, Prejudice and Discrimination: A European Report. Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Forum Berlin.

Zuckerman, Phil. 2015. Faith No More: Why People Reject Religion. New York: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out under the supervision of Prof. George Yancey and Dr. Nicholas Evangelopoulos. Responsibility for this work is mine alone.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grigoropoulou, N. Discussing God: The Effect of (Ir)Religious Identities on Topic-Sentiment Polarization in Online Debates. Rev Relig Res 62, 533–561 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-020-00425-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-020-00425-y