Abstract

Key message

We assessed the narrow-sense heredity and genetic gains of multiple traits obtained using the indirect selection method for progeny of Cryptomeria japonica D. Don by artificial crossing. Using stress wave velocity and Pilodyn penetration depth as indicative parameters, wood properties could be improved in future generations of C. japonica plus trees and forest breeding programs will become more efficient.

Context

To advance generations of C. japonica D. Don breeding populations, the narrow-sense heredity and genetic gain of traits of progenies are required to assess the practical genetic performance of parental trees and improve traits.

Aims

We assessed the genetic gains in both growth characteristics and wood properties by indirect selection using full-sib progenies of C. japonica plus trees produced through artificial crosses.

Methods

In 18-year-old progenies of 549 trees, we assessed growth characteristics, dynamic modulus of elasticity, basic density, stress wave velocity, and Pilodyn penetration depth. Genetic parameters were calculated using a mixed model and the breedR package.

Results

The genetic correlation between growth characteristics and wood properties was low. The efficiencies of indirect selection for dynamic modulus of elasticity by stress wave velocity and for basic densities by Pilodyn penetration depth were higher than those for growth characteristics by stress wave velocity and Pilodyn penetration depth, respectively. Strong correlations were found between the parental clonal values and breeding values of parental trees predicted from progeny using stress wave velocity and Pilodyn penetration depth.

Conclusion

Using stress wave velocity and Pilodyn penetration depth as indicative parameters, future generations of C. japonica plus trees could produce superior wood properties. Growth characteristics and wood properties are independent; thus, both traits could be genetically improved compatibly.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Wood property traits are of particular importance in forest tree breeding programs (Zobel and van Buijtenen 1989) because they are highly relevant to the physical and mechanical performance of wood products (Cown et al. 1995; Fujisawa 1998; Wessels et al. 2011). Modulus of elasticity (MOE) and wood density are the major traits that represent these mechanical properties. For example, MOE is strongly correlated with the breaking strength of wood (Castéra et al. 1996; Kijidani et al. 2010), whereas wood density is related to wood stiffness (Cown et al. 1995; Burdon et al. 2001). The latter also strongly affects tree carbon sequestration (Roderick and Berry 2001; Profft et al. 2009; Skovsgaard et al. 2011).

In most forest tree breeding programs, research that is aimed at simultaneously improving multiple traits, such as growth characteristics and wood properties, is ongoing (White et al. 2007). Improving multiple traits requires an understanding of both within- and among-tree variation for each trait as well as the genetic correlations among the traits of interest. Although good estimates of genetic parameters likely require a few hundred samples (Schimleck et al. 2019), wood property traits have generally been evaluated using surveys of felled trees, which is labor-intensive, expensive, and time-consuming. In addition, when using the standard destructive procedure that accompanies tree felling, it is difficult to obtain a sufficient number of samples from progeny or clonal tests because felling makes it difficult to continue the testing thereafter. Therefore, in many countries, nondestructive methods for investigating the traits of standing tree have been evaluated in major plantation tree species (Isik et al. 2011; Isik and Li 2003; Jones et al. 2005; Li et al. 2017; Pot et al. 2002; Raymond 2002; Schimleck et al. 2019; Wang et al. 1999; Wessels et al. 2011), and various nondestructive tools are now used in tree breeding programs and wood property breeding studies around the world (Apiolaza 2009; Schimleck et al. 2019).

Japanese cedar, Cryptomeria japonica D. Don, is one of the most important plantation tree species in Japan. Through the national forest tree breeding program, about 3700 first-generation plus trees have been selected from natural forests and artificial plantations with a focus on stem volume and stem form. The selection of second-generation plus trees, which are superior progenies of the first-generation plus tree clones, is ongoing. Pollination among selected second-generation plus tree clones will be conducted to set up a new breeding population and select for the third-generation plus trees in the future. In the second-generation plus tree selection criteria, both growth characteristics and wood property traits are major breeding targets. Evaluation of wood property traits in second-generation plus tree clones is performed using nondestructive procedures. The narrow-sense heritability of each trait and the genetic correlation among traits must be clarified if the improvement of multiple traits is to be optimized as generations of the breeding population advance. In addition, to advance wood property-focused breeding using nondestructive tools, it remains necessary to verify the usefulness of the nondestructive evaluation method based on full-sib progenies of the plus tree clones. Furthermore, it is not currently clear whether clonal values can be used as the proxy of the parental genetic abilities when selecting parents for controlled pollination among plus tree clones. The higher the ratio of additive effect over non-additive effect in wood property, the clonal value would well positively correlate with the breeding value. If this were the case, a large amount of data on the clonal wood properties of plus tree clones, which is often obtained in advance, could be utilized for the wood property breeding.

Previous studies on wood property inheritance and nondestructive evaluation methods for standing C. japonica trees have been mainly conducted using first-generation plus tree clones (Fukatsu et al. 2011; Fujisawa et al. 1992, 1994; Miyashita et al. 2009). Indeed, few data exist on the narrow-sense heritability of each trait, the genetic correlation between nondestructive evaluation values of standing tree and growth characteristics or wood properties, and the efficiency of indirect selection based on narrow-sense heritability.

In the present study, we evaluated optimal breeding strategies for improving both growth characteristics and wood properties using full-sib progenies of C. japonica plus tree clones. The specific research objectives in the study were to estimate (1) genetic gain by direct selection of multiple traits, (2) the phenotypic and genetic correlation among the traits, and (3) genetic gain by indirect selection of wood properties with nondestructive measurements, as well as to (4) compare the parental breeding wood property values estimated based on the progenies with their clonal wood property values.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant materials

The progeny test site used in the present study was established in 1995 at the Forest Tree Breeding Center (36.69° N, 140.69° E), Forest and Forest Products Research Institute, Hitachi City, Ibaraki Prefecture. The test was designed to include unbalanced randomized complete blocks of six replications with 1.8×1.8m spacing between trees (3000 individual/ha), mainly consisting of 45 full-sib families derived from eight sets of 4×4 half-diallel crosses using 32 C. japonica plus tree clones (Table 1). The number of trees in the experiment design was 2046 before the thinning. The thinning was conducted systematically, with an orthorhombic lattice pattern without paying attention to tree size in 2012 (stand age was 18 years), and the felled 549 full-sib progenies were used as the plant materials in the present study. There was a difference in the number of samples among parameters because the samples which were difficult to measure and calculate for each parameter were excluded (Table 2).

2.2 Growth characteristics and wood properties of standing trees

In November 2012, before thinning was performed, tree height (H; 0.1 m unit) and diameter at breast height (DBH; 0.1 cm unit) were measured at ~1.3 m above ground using a Vertex III (Haglof, Sweden) and caliper, respectively. Stress wave velocity (SWV; 1 m/s unit) was measured using a TreeSonic timer (FAKOPP, Hungary); specifically, start and stop sensors were installed, parallel to the axial direction of the trunk, at upper (1.7 m above ground) and lower (0.7 m above ground) positions, respectively (setting the section length to 1.0 m). SWV was measured in two perpendicular directions on the stem of standing trees. Measurements were taken five times each in one direction and the average value of 10 measured values was used as the individual value of each tree. Pilodyn penetration (PP; 0.1 mm unit) was measured using the Pilodyn 6J Forest instrument (Proceq Co., Switzerland) with an effective measurement range length of 0–40 mm and a pin diameter of 2.5 mm. During PP measurements, the device was first set facing the side of the standing tree’s trunk in two perpendicular directions at breast height and then the pin was driven toward the pith. This PP measurement was performed once in each direction and without removing the bark, and the average of two measured values was used as the individual values for each tree.

2.3 Wood properties of logs

After measuring growth characteristics, SWV, and PP, thinning was conducted and 1.5-m-long logs were taken from the felled individuals at a height of 1.0–2.5 m above ground. The dynamic modulus of elasticity (DMOE; 0.1 GPa unit) was measured by the tapping method (Sobue 1986) using an FFT analyzer AD-3527 (A&D, Tokyo, Japan). After the DMOE was measured, 10-cm-thick disks were collected from the breast height region; these were stored in natural conditions until basic density (BD; 0.001 g/cm3 unit) was measured. Strip samples in two directions centered on the pith were prepared from each disk. The specimens (segments) used to measure BD were made from strips divided every five annual rings from the pith using a chisel. BD was calculated as the oven-dried weight divided by the green wood volume, which was measured by the water displacement method. BD1, BD2, and BD3 were defined as the basic densities of the segments containing the 1st to 5th, 6th to 10th, and 11th to 15th annual rings, respectively. BD was not measured outside of the 16th annual ring. The mean BD of the entire disk (BDmean) was calculated by the weighted average method using the area of the BD1, BD2, and BD3 segments. All BDs (i.e., BD1, BD2, BD3, and BDmean) were measured in two directions using two strips, and the mean value was used as the individual value of each BD.

For comparison with the parental breeding values of PP and SWV estimated based on the progenies (mentioned below), we used respective clonal values measured by Mishima et al. (2011).

2.4 Statistical analysis

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated between traits as phenotypic correlations. The variance component and breeding value for each trait was estimated with a linear mixed model (Eq. 1) using the restricted maximum likelihood method (REML):

Here, Yijkl is a measurement value, μ is the general mean, Bi is a fixed effect of the block i, Gjkl is a random effect of the general combining ability (GCA) of an individual j for parents k and l, Skl is a random effect of the specific combining ability (SCA) of parents k and l, Bi × Skl is a random interaction effect for block i and parents k and l, and eijkl is a random residual effect. The abovementioned parameters of variances were estimated by the REML method. The random factors and individual tree breeding values were obtained by an “animal model” of best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP).

The narrow-sense heritability (h2) of each trait was estimated by Eq. 2:

Here, σ2g, σ2s, σ2bs, and σ2e are the variance components of GCA, SCA, the interaction of block × SCA, and the residual, respectively.

The genetic correlation between trait x and trait y was estimated using Eq. 3:

Here, rg(x, y) is the genetic correlation of trait x and trait y, COVg (x, y) is the covariance of trait x and trait y, and σ2g(x) and σ2g(y) are the variances of trait x and trait y, respectively. The variance components and genetic parameters, such as the narrow-sense heritability, genetic correlation, and breeding value, were calculated using the R package breedR (Munoz and Sanchez 2019) in R 3.6.1 (R Core Team 2019).

We also estimated the genetic gain obtained by direct selection and indirect selection for growth characteristics and wood properties. The genetic gain obtained by direct selection was calculated using Eq. 4:

Here, ΔGx is the genetic gain of trait x, i is the selection intensity, h2(x) is the narrow-sense heritability of trait x, and σg(x) is the standard deviation of the GCA effect at trait x. The genetic gain obtained by indirect selection was calculated with Eq. 5:

Here, ΔGx(y) is the genetic gain of trait x by selection with trait y, h2(y) is the narrow-sense heritability of trait y, and rg (x, y) is the genetic correlation between traits x and y. In both calculations, selection intensity i = 1 was applied (Falconer and Mackay 1996). The percentage of the genetic gain by direct selection from the mean of target trait x (relative genetic gain) and the efficiency of genetic gain by indirect selection compared to direct selection were calculated according to Fukatsu et al. (2015).

To examine the usefulness of evaluating parental abilities using clones, the parental breeding values obtained from the REML/BLUP procedures (described above) and the clonal values measured by Mishima et al. (2011) were correlated to calculate correlation coefficients for PP and SWV. In their study, three ramets were basically measured and used as the clonal value.

3 Results

3.1 Growth characteristics and wood properties

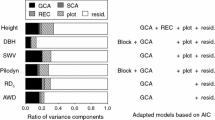

Data on growth characteristics and wood properties are given in Table 2. BD values decreased in the order of BD1, BD2, and BD3. The coefficient of variation (CV) of each wood property (8.6–19.0%) was less than the CV of each growth characteristic (20.2–27.1%). The narrow-sense heritability for each wood property (h2=0.353–0.503) was higher than that of H and DBH (h2=0.168 and 0.145, respectively). The relative genetic gains from direct selection (with selection intensity i=1) for growth characteristics and wood properties were similar (3.2–6.7%), as shown in Table 2. The ratio of variance components is shown in Fig. 1. The ratio of SCA was smaller than that of GCA for all traits.

The ratio of variance components for each trait. The abbreviations for traits are listed in Table 2. Additional definitions: GCA general combining ability, SCA specific combining ability, Block × SCA interaction effect between block and SCA, Residual random residual effect

3.2 Phenotypic and genetic correlations between traits

The phenotypic and genetic correlations between traits are shown in Table 3. A strong positive phenotypic correlation was observed between SWV and DMOE (r=0.847), whereas the phenotypic correlation between PP and BDmean was strongly negative (r=−0.729). Correlations between PP and BD1, BD2, and BD3 gave coefficients of −0.429, −0.632, and−0.768, respectively; these negative correlations were stronger at the bark side and weaker at the pith side. A strong positive genetic correlation was also observed between SWV and DMOE (rg(x, y)=0.901). The genetic correlations between PP and BD values, namely BD1, BD2, BD3, and BDmean, were again negative and largely strong, especially at the bark side, −0.534, −0.730, −0.870, and−0.797, respectively. The phenotypic and genetic correlations between growth characteristics (H and DBH) and wood properties measured after felling were weaker than the respective correlations with wood properties measured from standing trees.

3.3 Efficiency of indirect selection

The efficiencies of indirect selection (with a selection intensity of i=1) for growth characteristics and wood properties are presented in Table 4. The efficiency of indirect selection for DMOE by SWV (1.10) was higher than that for each BD (0.19–0.30). On the other hand, the efficiencies of indirect selection for BDs by PP (0.60–0.97) were higher than that for DMOE (0.11). Among the BD values, BD3 had the highest indirect selection efficiency value (0.97).

The efficiencies of indirect selection for H and DBH by SWV (0.56 and 0.50) were lower than that for DMOE (1.10). Similarly, the efficiencies of indirect selection for H and DBH by PP (0.13 and 0.55) were lower than those obtained for BDs (0.60–0.97).

3.4 Relationship between parental breeding values predicted by the progenies and their clonal values

For SWV and PP, correlations between parental breeding values predicted by the progenies and clonal values were assessed. For both SWV and PP, positive correlations (r=0.75 and r=0.69, respectively Fig. 2), were found between these values.

Scatter plot of measured parental clonal values (MV) and parental breeding values estimated from standing wood properties of artificial cross family traits (PBV). a Stress wave velocity (m/s). Pearson’s correlation coefficient = 0.75 (P < 0.001). b Pilodyn penetration depth (mm). Pearson’s correlation coefficient =0.69 (P < 0.001). For both traits, measured values in the parental clone (MV) are plotted against the breeding values of the parental clone (PBV), and each value is representative of the parental clone

4 Discussion

4.1 Inheritance for each trait

In the present study, the variance component ratios were calculated for growth characteristics (H and DBH) and wood properties (DMOE, BDs, SWV, and PP). The larger ratio of variance component of GCA than that of SCA for growth characteristics and wood properties (Fig. 1) have also been reported in other coniferous species including Pinus taeda L. (Isik and Li 2003; Isik et al. 2011), Pinus radiata D. Don (Gapare et al. 2010), and Larix kaempferi (Lamb.) Carr. (Fukatsu et al. 2015). In general, these results indicated that the genetic performance of a parent is additively transmitted to its progeny (White et al. 2007). Therefore, it would be possible to select superior progenies from superior parents for both growth characteristics and wood properties in C. japonica.

Although there have been many reports of broad-sense heritability in C. japonica (Fujisawa et al. 1992, 1994; Fukatsu et al. 2011; Miyashita et al. 2009), there are few data on narrow-sense heritability for wood properties. The repeatability of wood properties such as dynamic modulus of elasticity and basic density is known to be higher than that of growth characteristics such as tree height and diameter at breast height (Fujisawa et al. 1992, 1994; Fukatsu et al. 2011; Miyashita et al. 2009). In the present study, the narrow-sense heritability of each wood property in both logs and standing trees was also higher than that for the measured growth characteristics (Table 2). Therefore, in C. japonica, the phenotypes of wood properties appear to be affected less than the growth characteristics by environmental factors. Results such as this have also been reported for other coniferous species, e.g., P. taeda (Isik and Li 2003), P. radiata (Gapare et al. 2010; Kumari et al. 2002), Pinus sylvestris L. (Hong et al. 2014), and L. kaempferi (Fukatsu et al. 2015). Taken together, these results suggested that the inheritance of wood properties observed in the present study would be common to coniferous species. Again, this shows that superior progenies from superior parents could be selected for both growth characteristics and wood properties in C. japonica.

4.2 Efficiency of nondestructive measurement of wood properties

Here, a nondestructive wood property measurement method was assessed for its efficiency when evaluating the additive genetic performance for next-generation breeding with the progeny of C. japonica plus tree clones. High absolute values for phenotypic correlations between SWV and DMOE and between PP and BDs (Table 3) were also reported between stress wave velocity and dynamic modulus of elasticity in C. japonica (Miyashita et al. 2009) and other coniferous spices (Chen et al. 2015; Ishiguri et al. 2008; Schimleck et al. 2019; Wessels et al. 2011, 2015). Additionally, similar relationships between Pilodyn penetration depth and basic density have been reported in C. japonica (Fukatsu et al. 2011; Miyashita et al. 2009) and other conifers (Cown 1978; Cown and Hutchison 1983; Chen et al. 2015; dos Santos et al. 2016; Ishiguri et al. 2008; Schimleck et al. 2019). Obtaining a genetic correlation between two traits is an important aspect of validating a correlated response to selection or indirect selection among traits (White et al. 2007). In the present study, genetic correlations between SWV and DMOE and between PP and BDmean were evident (Table 3). In addition, the efficiencies of indirect selection for DMOE by SWV and for BDmean by PP (Table 4) suggest that, in forest tree breeding programs, C. japonica with high dynamic modulus of elasticity or high average basic density can be selected effectively using stress wave velocity and Pilodyn penetration depth as indirect selection indices. In addition, the genetic correlation between PP and BD3 was higher than between PP and either BD1 or BD2, indicating that it is possible to evaluate outer basic density (near the bark) accurately using Pilodyn penetration depth.

For both phenotypic and genetic correlations, correlation coefficients were low between SWV and BDs and between PP and DMOE (Table 3). The lower efficiency of indirect selection for BDs selected by SWV and for DMOE selected by PP and a weak genetic correlation between DMOE and BDs could be occurred because, in a previous study of C. japonica, dynamic modulus of elasticity was more strongly correlated with the microfibril angle of the S2 layer in latewood tracheids than with wood density (Hirakawa et al. 1997); thus, it appears to be difficult to improve wood density in this species using stress wave velocity as an indirect selection criterion. On the other hand, the genetic correlation between wood density and stress wave velocity has been reported to be strong in other coniferous species such as P. radiata, Picea abies (L.) Karst., and L. kaempferi (Apiolaza 2009; Chen et al. 2015; Fukatsu et al. 2015). Additionally, a positive correlation has been reported between dynamic modulus of elasticity and wood density in L. kaempferi (Ishiguri et al. 2008; Nakada et al. 2005; Tumenjargal et al. 2020). These findings suggest that the relationship between dynamic modulus of elasticity and wood density differs depending on tree species. Therefore, appropriate procedures for wood property breeding should be chosen according to species.

4.3 Relationship between the breeding values predicted by progenies and the clonal values of parental plus trees

By evaluating the genetic performance of the parental clones that contribute to the next generation, it is possible to plan the appropriate mating designs necessary for constructing next-generation breeding populations. In the present study, for SWV and PP, positive correlations were observed between the breeding values of the parent predicted from progenies and the clonal values of the first-generation plus trees (Fig. 2). These results indicate that, based on clonal values, it is possible to select superior parents for mating and superior families from existing breeding populations, which originated from artificial crossing between plus tree clones, before performing progeny tests with high accuracy. In C. japonica, wood properties for most of the first-generation plus tree clones have already been evaluated by stress wave velocity and Pilodyn penetration depth using their ramets (e.g., Mishima et al. 2011). Given the large amount of existing data on clonal wood properties, wood property improvement can be driven forward efficiently in C. japonica breeding programs.

4.4 Relationships between growth characteristics and wood properties

The weak genetic correlations among growth characteristics and wood properties (Table 3) and the lower efficiency of indirect selection for H and DBH by SWV and PP (Table 4) suggest that individuals with superior growth characteristics and wood properties can be selected, and that it would be possible to achieve genetic improvement in both growth characteristics and wood properties simultaneously. The weak phenotypic correlations between growth characteristics and wood properties in the present study are consistent with findings of previous C. japonica studies (Fujisawa et al. 1992, 1994; Fukatsu et al. 2011; Miyashita et al. 2009).

4.5 Application to tree breeding for wood properties in C. japonica

The results of the present study suggest that the growth characteristics of C. japonica (H and DBH) and the wood properties of its logs (DMOE and BD) are genetically independent; therefore, it should be possible to select C. japonica individuals with both superior growth and wood qualities. A progeny which has both superior traits may be produced by artificially mating a parent with superior growth and a one with superior wood property. Moreover, stress wave velocity and Pilodyn penetration depth, both of which are nondestructive measurements, were shown to be effective indices for evaluating dynamic modulus of elasticity and average basic density, respectively. Currently, the selection of second-generation C. japonica plus trees from a breeding population consisting of the progenies of the first-generation plus tree clones is underway. After the conventional evaluation of superior trees based on growth characteristics, by applying stress wave velocity and Pilodyn penetration depth during selection, it may be possible to select superior second-generation plus tree candidates, in terms of growth characteristics and wood properties, efficiently, and nondestructively.

The relatively large GCA component and positive correlation between the parental breeding values predicted from progenies and clonal values suggests that the clonal value of wood properties obtained by nondestructive measurements could be used as a proxy of the breeding value, i.e., a measure of genetic performance as parent which has been conventionally obtained by the progeny test. C. japonica has already been comprehensively evaluated for clone of first-generation plus trees, and we thought that this evaluation can be effectively used for future selection and creation of the next generation. Clonal values as the parental genetic performance also suit seed production in seed orchards, in which random mating of parents is assumed. In other words, by creating a seed orchard from C. japonica second-generation plus tree clones with superior growth characteristics and wood properties, it may be possible to produce C. japonica seedlings with superior growth characteristics and wood properties.

5 Conclusions

In this study, we clarified the genetic gains in wood property by indirect selection using nondestructive measurements based on full-sib families derived from half-diallel crosses of C. japonica plus tree clones. We showed that the growth characteristics and wood properties of C. japonica could be improved independently and that stress wave velocity and Pilodyn penetration depth were effective indirect selection indices for breeding. Indeed, stress wave velocity and Pilodyn penetration depth have become indispensable indicators of wood property improvement in forest tree breeding programs. Since the relationship between growth characteristics and wood properties differs depending on tree species, genetic evaluation must be performed after selecting an appropriate indirect evaluation method according to the tree species or age.

We also showed that clonal wood property data in first-generation plus tree clones is useful for advancing the breeding of this species. Second-generation plus tree clones, which have been selected and propagated from breeding populations, are currently preserved and evaluated for growth traits. In addition, assessing the wood properties of these trees in the clonal archives using nondestructive measurements would provide further data for use when breeding the next advanced generation. Based on these nondestructive measurements and clonal wood properties data, it should be possible to advance C. japonica breeding more effectively and efficiently.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Apiolaza LA (2009) Very early selection for solid wood quality: screening for early winners. Ann For Sci 66:601. https://doi.org/10.1051/forest/2009047

Burdon RD, Britton RAJ, Walford GB (2001) Wood stiffness and bending strength in relation to density in four native provenances of Pinus radiata. New Zeal J For Sci 31:130–146

Castéra P, Faye C, El Ouadrani A (1996) Prevision of the bending strength of timber with a multivariate statistical approach. Ann For Sci 53:885–898. https://doi.org/10.1051/forest:19960407

Chen ZQ, Karlsson B, Lundqvist SO, García Gil MR, Olsson L, Wu HX (2015) Estimating solid wood properties using Pilodyn and acoustic velocity on standing trees of Norway spruce. Ann For Sci 72:499–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-015-0458-9

Cown DJ (1978) Comparison of the Pilodyn and torsiometer methods for the rapid assessment of wood density in living trees. New Zeal J For Sci 8:384–391

Cown DJ, Hutchison JD (1983) Wood density as an indicator of the bending properties of Pinus radiata poles. New Zeal J For Sci 13:87–99

Cown DJ, Walford B, Kimberley MO (1995) Cross-grain effect on tensile strength and bending stiffness of Pinus radiata structural lumber. New Zeal J For Sci 25:256–262

dos Santos GA, Nunes ACP, de Resende MDV, Silva LD, Higa A, de Assis TF (2016) An index combining volume and Pilodyn penetration to study stability and adaptability of Eucalyptus multi-species hybrids in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Aust For 79:248–255

Falconer DS, Mackay TFC (1996) Introduction to quantitative genetics, 4th editon. Prentice Hall, Harlow

Fujisawa Y (1998) Forest tree breeding systems for a forestry based on the concept of quality management considering the production of high level raw materials. Bull Tree Breed Cent 15:31–107 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Fujisawa Y, Ohta S, Nishimura K, Tajima M (1992) Wood characteristics and genetic variations in sugi (Cryptomeria japonica): clonal differences and correlations between locations of dynamic moduli of elasticity and diameter growths in plus-tree clones. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 7:638–644

Fujisawa Y, Ohta S, Nishimura K, Toda T, Tajima M (1994) Wood characteristics and genetic variations in sugi (Cryptomeria japonica). III. Estimation of variance components of the variation in dynamic modulus of elasticity with plus-trees clones. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 40:457–464

Fukatsu E, Tamura A, Takahashi M, Fukuda Y, Nakada R, Kubota M, Kurinobu S (2011) Efficiency of the indirect selection and the evaluation of the genotype by environment interaction using Pilodyn for the genetic improvement of wood density in Cryptomeria japonica. J For Res 16:128–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10310-010-0217-6

Fukatsu E, Hiraoka Y, Matsunaga K, Tsubomura M, Nakada R (2015) Genetic relationship between wood properties and growth traits in Larix kaempferi obtained from a diallel mating test. J Wood Sci 61:10–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10086-014-1436-9

Gapare WJ, Ivković M, Baltunis BS, Matheson CA, Wu HX (2010) Genetic stability of wood density and diameter in Pinus radiata D. Don plantation estate across Australia. Tree Genet Genomes 6:113–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-009-0233-x

Hirakawa Y, Yamashita K, Nakada R, Fujisawa Y (1997) The effects of S2 microfibril angles of latewood tracheids and densities on modulus of elasticity variations of sugi tree (Cryptomeria japonica) logs. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 43:717–724 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Hong Z, Fries A, Wu HX (2014) High negative genetic correlations between growth traits and wood properties suggest incorporating multiple traits selection including economic weights for the future Scots pine breeding programs. Ann For Sci 71:463–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-014-0359-3

Ishiguri F, Matsui R, Iizuka K, Yokota S, Yoshizawa N (2008) Prediction of the mechanical properties of lumber by stress-wave velocity and Pilodyn penetration of 36-year-old Japanese larch trees. Holz Roh Werkst 66:275–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-008-0251-7

Isik F, Li B (2003) Rapid assessment of wood density of live trees using the Resistograph for selection in tree improvement programs. Can J For Res 33:2426–2435. https://doi.org/10.1139/x03-176

Isik F, Mora CR, Schimleck LR (2011) Genetic variation in Pinus taeda wood properties predicted using non-destructive techniques. Ann For Sci 68:283–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-011-0035-9

Jones PD, Schimleck LR, Peter GF, Daniels RF, Clark III A (2005) Nondestructive estimation of Pinus taeda L. wood properties for samples from a wide range of sites in Georgia. Can J For Res 35:85–92

Kijidani Y, Hamazuna T, Ito S, Kitahara R, Fukuchi S, Mizoue N, Yoshida S (2010) Effect of height-to-diameter ratio on stem stiffness of sugi (Cryptomeria japonica) cultivars. J Wood Sci 56:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10086-009-1060-2

Kumari S, Jayawickrama KJS, Lee J, Lausberg M (2002) Direct and indirect measures of stiffness and strength show high heritability in a wind-pollinated radiata pine progeny test in New Zealand. Silvae Genet 51:256–261

Li Y, Suontama M, Burdon RD, Dungey HS (2017) Genotype by environment interactions in forest tree breeding: review of methodology and perspectives on research and application. Tree Genet Genomes 13:60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-017-1144-x

Mishima K, Iki T, Hiraoka Y, Miyamoto N, Watanabe A (2011) The evaluation of wood properties of standing trees in sugi (Cryptomeria japonica) plus tree clones selected in Kanto breeding region. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 57:256–264 (in Japanese with English abstract). https://doi.org/10.2488/jwrs.57.256

Miyashita H, Orita H, Handa T (2009) Evaluation of the wood quality of young Cryptomeria japonica clones. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 55:136–145 (in Japanese with English abstract). https://doi.org/10.2488/jwrs.55.136

Munoz F, Sanchez L (2019) breedR: statistical methods for forest genetic resources analysts. R package version 0.12–4. https://github.com/famuvie/breedR. Accessed 28 Aug 2020

Nakada R, Fujisawa Y, Taniguchi T (2005) Variations of wood properties between plus-tree clones in Larix kaempferi (Lamb.) Carriere. Bull Tree Breed Cent 21:85–105 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Pot D, Chantre G, Rozenberg P, Rodrigues JC, Jones GL, Pereira H, Hannrup B, Cahalan C, Plomion C (2002) Genetic control of pulp and timber properties in maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Ait.). Ann For Sci 59:563–575. https://doi.org/10.1051/forest:2002042

Profft I, Mund M, Weber GE, Weller E, Schulze ED (2009) Forest management and carbon sequestration in wood products. Eur J For Res 128:399–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-009-0283-5

R Core Team (2019) A language and environment for statistical computing. R version 3.6.1. In: R Found Stat Comput Vienna, Austria. https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/3.6.1/. Accessed 1 Sep 2019

Raymond CA (2002) Genetics of Eucalyptus wood properties. Ann For Sci 59:525–531. https://doi.org/10.1051/forest:2002037

Roderick ML, Berry SL (2001) Linking wood density with tree growth and environment: a theoretical analysis based on the motion of water. New Phytol 149:473–485. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00054.x

Schimleck L, Dahlen J, Apiolaza LA, Downes G, Emms G, Evans R, Moore J, Pâques L, van den Bulcke J, Wang X (2019) Non-destructive evaluation techniques and what they tell us about wood property variation. Forests 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10090728

Skovsgaard JP, Bald C, Nord-Larsen T (2011) Functions for biomass and basic density of stem, crown and root system of Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) in Denmark. Scand J For Res 26:3–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2011.564381

Sobue N (1986) Measurement of Young’s modulus by the transient longitudinal vibration of wooden beams using a fast Fourier transformation spectrum analyzer. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 32:744–747

Tumenjargal B, Ishiguri F, Iki T, Takahashi Y, Nezu I, Otsuka K, Ohshima J, Yokota S (2020) Clonal variations and effects of juvenile wood on lumber quality in Japanese larch. Wood Mater Sci Eng:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/17480272.2020.1779809

Wang T, Aitken SN, Rozenberg P, Carlson MR (1999) Selection for height growth and Pilodyn pin penetration in lodgepole pine: effects on growth traits, wood properties, and their relationships. Can J For Res 29:434–445. https://doi.org/10.1139/x99-012

Wessels CB, Malan FS, Rypstra T (2011) A review of measurement methods used on standing trees for the prediction of some mechanical properties of timber. Eur J For Res 130:881–893. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-011-0484-6

Wessels CB, Malan FS, Seifert T, Louw JH, Rypstra T (2015) The prediction of the flexural lumber properties from standing South African-grown Pinus patula trees. Eur J Forest Res 134:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-014-0829-z

White TL, Adams WT, Neale DB (2007) Forest genetics

Zobel BJ, van Buijtenen JP (1989) Wood variation: its causes and control

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation to all the staff of the Forest Tree Breeding Center of the Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute for their assistance in conducting this study. We would also like to express our gratitude to M. Suzuki and J. Orita for their assistances in measuring wood properties.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Ricardo Alia

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contribution of the co-authors Conceptualization: TI; Methodology: YY, TI, YT; Formal Analysis: YY, TI, YT; Investigation: TI, YT, YH; Resources: TI, YT, YH; Data curation: YY, TI, YT; Data provision: KM, Writing—original draft: YY; Writing—revising: MT, Visualization: YY; Supervision: TI, YT, MT, YH, KM.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yasuda, Y., Iki, T., Takashima, Y. et al. Genetic gains in wood property can be achieved by indirect selection and nondestructive measurements in full-sib families of Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica. D. Don) plus tree clones. Annals of Forest Science 78, 50 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-021-01064-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-021-01064-1