Abstract

Subsistent beekeeping has been an established tradition in Tigray, northern Ethiopia. In the last two decades, extension efforts tried to transform it into improved apiculture, which led to development of colony marketing. Here, we assessed the progress in beekeeping, colony marketing, and population differentiation with a hypothesis that the extension might have supported both production and genetic conservation in accordance with the national apiculture proclamation. Progress in beekeeping was analyzed based on official annual reports from 2004 to 2020. In addition, colony market survey was conducted in one of the central markets to analyze spatial and agro-ecological zone (AEZ) distributions of the honey bees, driving factors, and implications by interviewing 120 sellers and buyers. Moreover, highland and lowland honey bee population differentiation was compared in two areas (not-) involved in marketing using a nuclear marker known for elevational adaptation. The regional beekeeping progressed substantially: frame hives grew from 1 to 23%, annual honey production tripled, managed colonies increased by 90%. Frame hives provided significantly (F = 88.8, P < 0.001) higher honey yield than local hives. Colonies were exchanged between actors with significant differences in spatial (X2 = 104.56, P < 0.01) and AEZ (X2 = 6.27, P = 0.044) distributions. Colonies originate mainly from highland areas of two districts and were re-distributed to broader areas. Most buyers showed preferences for colony color (73.3%) and AEZ of origin (88.3%), which led to a one-way flow. Consequently, no genetic differentiation was detected between two contrasting elevations in the involving district compared to a not involving area (FST = 0.22). Overall, the regional apiculture progressed significantly, but there is no evidence that the extension contributed to conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The honey bee Apis mellifera is known to be one of the most useful insects because of its crucial roles in the global food production, household income, employment, and ecosystem service through its pollination and beekeeping products (Bradbear 2003; Jones et al. 2016). According to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES 2016), pollinator-dependent crops contribute to 35% of the total crop production world-wide. Apis mellifera plays major contribution to the production of important crops such as coffee and several edible fruits (Geeraert et al. 2020; Porto et al. 2020). Overall, the honey bee is socially, economically, and environmentally beneficial insect which is ranked as the second most economically important livestock species with an estimated annual contribution of USD 180 Billion (Jacobs et al. 2006). The honey bee is the most widespread managed pollinator in the world, where an estimated 81 million colonies produce 1.6 million tons of honey annually (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services [IPBES] 2016).

In Ethiopia, the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) (CSA 2021) reported about seven million managed colonies distributed throughout different agro-ecological zones (AEZs). Beekeeping plays important roles to the livelihood of smallholder farmers in the country (Girma and Gardebroek 2015; Tarekegn and Ayele 2020; Gratzer et al. 2021). There has been a close relationship between the honey bees and human beings, in which traditional beehives are often installed inside the walls of residential houses and backyards throughout the rural areas of Ethiopia (Bogale 2009; Hailu and Tesfay 2012). Beekeeping products, mainly honey and beeswax, are highly valued and have been used in the country since ancient times (Gratzer et al. 2021). Honey-wine (mead, locally miyes), which is a fermented product of crude honey harvested from traditional beehives, has remained to be among the main beverages in many areas of Ethiopia such as Tigray (Bahiru et al. 2001; Dhyani et al. 2019).

Nonetheless, the productivity of Ethiopian beekeeping had been marginal. For example, annual honey yield was estimated at 8.3 kg per hive in 2018 (FAO 2018) in contrast to a 35–45-kg estimated potential (Jacobs et al. 2006). Hence, the potential of apiculture for addressing socio-economic challenges (Bradbear 2003) is under-utilized. To change this situation, there have been efforts of apicultural development extension aiming at improving production through capacity building and introducing movable frame beehives and accessories (Abebe et al. 2008; Tarekegn and Ayele 2020), with a focus to integrate young people into beekeeping. Movable frame hives such as the Langstroth were reported to provide higher yield of honey compared to the traditional system in Tigray (Yirga and Gidey 2010) because they allow better management of colonies (Langstroth 1852). The promotion of beekeeping created increased demand for honey bee colonies and subsequently, colony marketing developed as an important means of earning income for some beekeepers and traders in northern Ethiopia, particularly Tigray (Nuru 2002; Teweldemedhn and Yayneshet 2014b) and Amhara regional states (Dessalegn et al. 2010). In Tigray, there are central market places such as Nebelet, Maikinetal, and Enticho towns, which are used as the main sources of colony in the region. Colony transportation that involves wide distances could be detrimental to the genetic diversity and health of the local honey bees. It is well documented that trade of honey bee queens and migratory beekeeping had severe impacts on the health and genetic diversity in north America and Europe (De La Rúa et al. 2009; Meixner et al. 2010). A recent study indicated an extensive gene flow across AEZs among the honey bees of Tigray (Hailu et al. 2021). In light of the importance of beekeeping and the need to conserve the honey bees, Ethiopia enacted a proclamation entitled “Apiculture Resources Development and Protection” (Federal Parliament 2009), which aims to develop and protect the honey bees.

Overall, it can be hypothesized that the apicultural extension could be promoting both beekeeping and conservation in accordance with the national proclamation. Therefore, the marketing of honey bee colonies in Tigray may not lead to significant impact on the genetic diversity. The alternative hypothesis would be that the extension might have focused on apicultural development without attention to the honey bee conservation and the risks of colony marketing or transportation. Assessing the trends in apicultural development based on long-term average yields of the traditional and improved production systems, their proportions, and relationships with genetic diversity and gene flow in the local honey bee A. m. simensis subspecies (Meixner et al. 2011; Hailu et al. 2020) would contribute to setup sustainable development strategies for the sub-sector.

In this study, we aimed to provide insights into the apicultural development, and the honey bee gene flow in the context of a unique colony marketing practice in Tigray regional state, a major beekeeping area in northern Ethiopia. The region is characterized by largely semi-arid climate, high density of human population and fragmented landholding. It had been recently trying to transform its deep-rooted traditional beekeeping that uses fixed-comb hives to movable-frame hives with a goal of contributing to food security, employment, and overall poverty alleviation efforts. The interventions increased demand for colony management, which created an opportunity for some beekeepers to generate income through marketing.

2 Material and methods

This study was conducted to get insights into the apicultural development progress achieved and its relations with the honey bee colony marketing and gene flow in Tigray — a major beekeeping area in Ethiopia. Tigray is a regional state located in northern Ethiopia; bordering with Eritrea in the north and Sudan in the west (Figure 1c). The region is selected for this study based on its beekeeping potential, pronounced apicultural transformation over the last decades (CSA 2020), existence of colony marketing practice (Teweldemedhn and Yayneshet 2014b) and logistics. The study has two parts: analyses on the progress of apicultural development and honey bee colony market survey.

Percentages of honey bee colonies in Enticho market by districts of origin and destination; and location maps. a Three districts of origin of honey bee colonies collected into Enticho market place of Tigray region. b Eight districts of destination of honey bee colonies bought in the market place. c Map of Ethiopian regional states — displaying Tigray marked in the northern part. d Districts map of Tigray — showing the location of districts of honey bee colony origin and destination as well as the colony marketplace of Enticho town. The maps are produced using ArcMap 10.6.

2.1 Beekeeping progress assessment

Three beekeeping systems are officially recognized in Ethiopia as traditional (fixed-comb), transitional (top-bar) and modern (movable frame); of which the traditional is dominant and the transitional constitute the least. Apicultural development initiatives had been focusing on the introduction of movable frame hives with the aim of improving productivity which led to increased beekeeping and colony marketing mainly in Tigray region.

Therefore, we assessed the beekeeping progress in Tigray achieved over the last 16 years based on official data from the annual reports of the national central statistical agency (CSA) covering the production years 2004 to 2020 to get insights into the productivity of the two main beekeeping systems and colony population growth. CSA conducts an annual agricultural survey among private peasant holdings including livestock and livestock characteristics. Out of these, the number and type of beehives and honey production summarized, and yield as well as rates of annual growth analyzed. Moreover, honey yield was compared between the local traditional hives and movable frame hives using one-way ANOVA after confirming normal distribution of the data.

2.2 Honey bee colony market survey and population genetic analysis

The honey bee colony market survey was conducted in Enticho, which is a town located in Central zone of Tigray regional state. Honey bee colony marketing is organized on weekly basis every year during the rainy season where colony exchange takes place between sellers and buyers. This market was selected based on its size and proximity to honey bee sampling sites for previously completed molecular and morphological components of this project (Hailu et al. 2020, 2021). The survey data were collected by interviewing 120 honey bee colony sellers (60) and buyers (60)—selected using stratified random sampling—using semi-structured questionnaires during five market days between 27 July 2019 and 24 August 2019. The sample covered about 10% of the population in each market day based on previous information from similar markets in the region (Teweldemedhn and Yayneshet 2014a). Interviewees responded to questions on different variables including beekeeping experience, extension services received, geographic location (districts representing for spatial distribution), and means of transport. The number of colonies purchased per person, purpose of buying (honey, colony), type of hive to be used, preferred AEZ of origin (highland, midland, lowland), and color of honey bees (black, golden, hybrid), and reasons for buying in the market were studied based on the buyers’ responses. In addition, information on the number of colonies sold per person, method of acquiring (trapping, swarming, splitting, trade), were gathered from the sellers.

The data were summarized using descriptive statistics and significance tests conducted. Beekeeping experience, extension services received, spatial and AEZ (origin and destination) of colony distributions were included as factors whereas market actors’ role, preferences for color and AEZ of origin, purpose of production, type of hive planned to be used, method of acquiring colonies supplied to the market, and means of transport were analyzed as response variables using chi-square (X2). Statistical analysis was performed using JMP® Pro 15 (SAS, USA).

Furthermore, highland (≥ 2468 m above sea level) and lowland honey bee population differentiation by means of FST, a measurement for genetic differentiation, (Wright 1951) was analyzed and compared in areas (not-)involved in marketing using a nuclear marker from a published sequence data (Hailu et al. 2021). This marker is located within the gene octopamine receptor beta-2R (LOC412896) on chromosome seven near a potential chromosomal breakpoint and was hypothesized to provide genetic basis of local adaptation to habitat elevation in East African honey bees (Wallberg et al. 2017).

3 Results

3.1 Progress in beekeeping

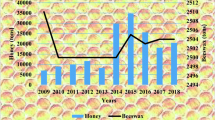

The total number of honey bee colonies in Tigray region raised from 173,948 in 2004 to 332,391 in 2020 (CSA 2004, 2021), which is an increase of about 90% and an average annual growth rate of 7%. As a result, annual honey production increased from 1377 to 4739 tons. With a 52% average annual growth, the number of movable frame hives in the region reached 75,109 in 2020 starting with 1503 in 2004. This elevated the proportion of movable frame hives from 1 to 23% during the specified period; whereas the number of traditional hives grew at an annual average of 5%. The numbers of honey bee colonies managed and annual honey production in Tigray during the study period are summarized in Figure 1. The introduced movable frame hives provided significantly higher (F = 88.8; P < 0.001) annual honey yield compared to the local traditional (fixed-comb) hives over the period 2004 to 2020. Mean yield of honey out of the movable frame beehives was 19.9 kg per hive per year. In contrast, the yield of honey from that of the local traditional hives was 10.7 kg per hive per year for the same period.

3.2 Honey bee colony marketing and genetic consequence

In association with an overall increased interest to use beekeeping for poverty alleviation through apicultural development interventions, the total number of honey bee colonies managed in Tigray showed substantial increase over the last two decades. In the meantime, honey bee colony production and trading emerged as an important commodity for smallholder beekeepers in the region. By conducting honey bee colony market survey in one of the major colony markets in Tigray, we explored the origin and destination of the colonies, beekeeping-related backgrounds of the market actors, why they chose to participate in this practice, and analyzed the genetic consequence of this practice.

3.2.1 Background of market actors

Almost all of the market actors in Enticho, a central honey bee colony market place in Tigray region of northern Ethiopia, were men with a small fraction (6%) of women participating in selling but not in buying colonies. Considering beekeeping background, most of the sellers (92%) were experienced beekeepers who produce colonies and supply to the market mainly using traditional hives (98%), which are small size fixed-comb hives locally made for this purpose. The sellers owned higher number of stock colonies managed in traditional hives (8.18 ± 5.44 per person) compared to that of the buyers. In addition, there were a few traders (8%) who supplied more colonies (16.61 ± 19.7 per season) by collecting from different villages compared to the number of colonies supplied by the producers (11.41 ± 15.7 per season) who use swarming to reproduce their own colonies. The sellers supplied an average of 3.02 ± 2.47 colonies, whereas the buyers needed 1.63 ± 0.92 colonies per person per market day. Seasonal target of the buyers was to purchase 2.23 ± 1.43 colonies per person. Majority of the buyers (70%) were beekeepers who manage fewer colonies in traditional (2.2 ± 1.3) and frame hives (1.3 ± 3.2) for honey production. Overall, the buyers of colonies composed of both experienced beekeepers and beginners, who use or planned to use both local and frame hives for honey production (Table I).

3.2.2 Spatial and agro-ecological distribution of colonies

Three districts — namely Ganta-Afeshum, Ahferom, and Gulomokeda — were identified as the sources of honey bee colonies for Enticho colony market. Most of the colonies in the market were originated from the highland areas of Ganta-Afeshum (51.7%) and Ahferom (40%) districts while Gulomokeda district contributed a small fraction (Figure 1a).

Based on mean number of colonies supplied per person from the districts, the sellers from Ganta-Afeshum district contributed the highest (3.81 ± 0.42 per day; 16.35 ± 2.77 per season) while those from Ahferom supplied the least (1.96 ± 0.48 per day; 5.83 ± 3.14 per season). Swarming of own colonies and trade by collecting colonies from beekeepers by roaming house-to-house in villages — which varied between districts (X2 = 13.16, P = 0.011) — were the only means of acquiring colonies supplied for the market. Trade accounted for majority of the colonies supplied from Gulomokeda (60%) whereas production of own colonies through reproductive swarming was the main source of colonies for sellers who came to the market from Ahferom (87.5%) and Ganta-Afeshum (54.8%) districts. Sellers from Gulomokeda and Ganta-Afeshum acquired highest number of colonies per person by means of trade (Figure 2). On the other hand, eight districts were recorded as destinations of the honey bee colonies. Adwa district was the most frequently (41.7%) mentioned address of the honey bee colony buyers. This was followed by Ahferom (20%) and Laelay-Machew (13.3%) districts (Figure 1b).

Numbers of honey bee colonies per person supplied to Enticho market place disaggregated by methods of acquiring the colonies (production of own colonies using swarming or collection of colonies roaming house-to-house in villages) by the sellers from Ahferom, Ganta-Afeshum, and Gulomokeda districts. The traders brought by far larger numbers of colonies compared to the ones who reproduce and sell their own colonies in the market, indicating a further specialization on colony trade.

Overall, the marketing involved exchange of honey bee colonies up to 135-km aerial distance (Figure 3d). Therefore, there was significant difference between the sellers (origin of colonies) and buyers (destination of colonies) in spatial (X2 = 104.56, P < 0.01) and agro-ecological zones (X2 = 6.27, P = 0.044) of (re-)distributions. Transportation of the honey bee colonies to/from the market was carried out using either personal labor who travelled on foot or public transport with minibuses; depending on road access and distance from the market. Most of the buyers (87%) used public transport vehicles while majority of the sellers (55%) traveled on foot (Figure 4). The main risks encountered when transporting on foot were breakage of honey combs and death of bees due to stress. Transportation on the roof top of minibuses driven on the asphalt roads was said to be safer as it offers fresh air to the bees through a meshed cover on the hives and shortens the duration of travel.

Numbers of beehives managed and annual honey production in Tigray during the production years of 2003/4 to 2020/21 summarized from annual reports published by the Ethiopian central statistical agency (CSA). a Total number of beehives, b local traditional (TDH) and movable frame (MFH) hives used, c annual honey produced over the specified period, d an apiary of MFH established and owned by Haleka Alem in a landscape rehabilitation (area enclosure) in Wukro, Tigray.

3.2.3 Driving factors of colony marketing

Firstly, we compared the numbers of the honey bee colony sellers and buyers based on their beekeeping status and extension supports that they received as factors. Considering beekeeping experience of the market actors, the proportion of buyers (70%) was significantly lower compared to the sellers (92%) (X2 = 9.55, P = 0.002). Further, governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) provided different support services as confirmed by a number of the buyers (23.3%) and sellers (33%). However, there was no difference between the number of sellers and buyers who received any extension service, the types of service (technical, inputs), or type of organizations who offered the services (government, NGOs).

Next, we looked into the market actors’ sentiments. As previously stated, the honey bee colony sellers were composed of both experienced beekeepers and traders who collect colonies from villages; roaming to production areas. The sellers who had beekeeping experience responded that their areas are too cold for honey production. Hence, most of them (91.5%) stated colony production and marketing as more profitable than honey production in their local areas. The beekeepers stimulate their honey bees to make reproductive swarming by overcrowding in small hives, frequently smoking with selected plants, and removing old combs. The central market place was a preferred option for selling the colonies because of low demand (91.7%) and price (6.7%) in their villages, and an interest to combine it with other marketing activities in the town (1.7%).

Similarly, the buyers justified the central market place as a better option over other alternatives. They explained that it was less probable to succeed (46.7%), time consuming (11.7%), not interesting (11.7%), and low quality of colonies as the reasons why they did not trap colonies in their local areas. Lack of supply (63.3%), low quality (8.3%), and high prices (5%) hindered them from buying colonies in their respective villages. Either they did not have necessary skill (60%) or were not interested (40%) to reproduce their own colonies although majority of them (70%) had the stock. Greater proportion of the buyers showed preferences between black, yellowish, and hybrid honey bees (73.3%) as well as highland, midland, and lowland AEZs of origin of the colonies (88.3%). A large proportion of the respondents preferred black bees originated from highland areas (Table II). They perceived that the black bees are more productive of honey but aggressive (defensive); whereas the golden (yellowish) bees were preferred for their gentle behavior. Exposure to beekeeping extension service and experience did not show significant influence on the buyers’ preferences for color and AEZ of origin of the honey bees.

Moreover, the purpose of purchasing honey bee colonies among the buyers was assessed in order to understand whether they planned to produce honey, colonies, or any other. Almost all the interviewed purchasers (95%) of colonies responded honey production as the sole purpose of buying the colonies. Majority of the purchasers planned to use local (traditional) beehives, no matter whether they received extension support or not (Figure 5). A beekeeping extension service in the region includes training and technical or financial inputs to start up or improve an existing beekeeping (Abebe et al. 2008; Yirga and Gidey 2010).

Proportion of buyers based on their plan to manage the colonies in local and frame beehives disaggregated by beekeeping extension service that they received. The beekeeping extension increases use of frame hives’ nonetheless, a vast majority of the colonies remained to be managed in local traditional beehives.

As a consequence of marketing and transportation, the honey bee colonies were flowing uni-directionally from a few mountainous areas. The practice eroded the genetic differentiation based on elevation. This was clearly observed between two contrasting elevations in one of the main marketing areas known as Mugulat, compared to a strong differentiation between Werie valley and the highland areas in this district (Table III).

4 Discussion

Apicultural development efforts achieved tremendous progress in honey production through the introduction of high yielding movable frame hives, capacity building, and increasing overall managed colonies in Tigray region (Figure 3). Frame hives provided significantly higher (19.9 kg per hive per year) honey yield than the traditional hives in the region (10.7 kg per hive per year), which agrees with previous reports (Yirga and Gidey 2010). Movable frame hives are designed to suit colony management and increase productivity with the support of comb-foundation sheets (Langstroth 1852; Bradbear 2003), but there have been concerns of bee health and sustainability associated with large size artificial comb cells (Calderón et al. 2010; Loftus et al. 2016; Blacquière et al. 2019). Based on FAOSTAT (FAOSTAT 2021), honey yield (kg/hive) ranged from 6.9 (Ethiopia), 10 (Kenya), and 10.3 (African average) in 1993 to 8.6, 12.2, and 10.9, respectively, in 2019. The figures show an improving trend but average yield in Ethiopia is lower than neighboring countries and continental average due to lower base and a dominantly traditional production system. An estimate on the potential of beekeeping in Tigray region of Ethiopia shows that up to 45 kg of honey can be harvested per hive seasonally (Jacobs et al. 2006), which indicates a long way to go in narrowing the yield gap. Development endeavors in Ethiopia in general and in Tigray in particular had been trying to improve the productivity of beekeeping by introducing improved equipment, capacity building and creating market linkage (Abebe et al. 2008; Girma and Gardebroek 2015; Tarekegn and Ayele 2020). Capacity building and awareness raising on the use of improved beehives, bee flora development, and conservation were reported to have positively influenced the rate of adoption of improved equipment and enhanced the technical efficiency of beekeepers in southern Ethiopia (Tarekegn and Ayele 2020). Moreover, a contractual organic honey production to supply for processors and exporters provided better price and improved the beekeeping income in this area (Girma and Gardebroek 2015). In northern Ethiopia, efforts were focused at integrating improved beekeeping with rehabilitation of degraded hillsides for creating livelihood opportunity to unemployed youth. Additional costs invested in frame hives can be offset by the almost double yield of honey per hive per year compared to the traditional hives analyzed in the region as an average for the study period. Previously conducted economic analyses showed that modern beekeeping system integrated with hillside area rehabilitation was viable and profitable: 50% breakeven, large positive net present value, and higher internal rate of return than local bank interest rates (Gebretinsae and Stellmacher 2018).

Altogether, the development interventions resulted in increasing the Tigray regional beekeeping activity; raising the total number of managed honey bee colonies by 90%, proportion of movable frame hives from 1 to 23% and annual honey production more than three folds during the period 2004 to 2020 (Figure 3). Ethiopian national figures indicate 65% increase in the total number of honey bee colonies over the same period including a total of 3% frame hives in 2020 (CSA 2004, 2021). A recent review on an extended period based on FAOSTAT reported that number of colonies increased by 72% from 1993 to 2018 at national level (Gratzer et al. 2021). Following the trends in production, honey export volume continued to grow from 274 tons in 2009, to 727 tons in 2012 and 883 tons in 2013 (Girma and Gardebroek 2015). However, demands for honey bee pollination service of cultivated crops outpaced the growth in managed colony population in the country (Gratzer et al. 2021), which indicate the need to further exploit the beekeeping potential.

The overall increased interest to use beekeeping for poverty alleviation led to increased demand to manage colonies (Teweldemedhn and Yayneshet 2014b), which created an opportunity for some colony producers and traders to generate income out of this commodity (Nuru 2002). In light of the trends, the importance of the honey bee colony production and marketing would be increasing. Characterization of the market actors and the patterns of colony redistribution will help to understand the genetic and socio-economic significance of this practice.

The honey bee colony market survey of this study showed that virtually all of the market actors involved as sellers and buyers of honey bee colonies are men with a little participation of women in selling but none in buying. Previous studies indicated that women account a considerable proportion of the buyers, which implied their increasing engagement in beekeeping in different regions of Ethiopia such as Amhara (Dessalegn et al. 2010) and Tigray (Teweldemedhn and Yayneshet 2014b). However, the none-existence of any female among the buyers in this survey who aim to begin beekeeping does not support the claim. This may relate to differences among areas as previously observed in two market places in Tigray (Teweldemedhn and Yayneshet 2014a). It has been emphasized that both men and women particularly in rural areas can improve their livelihoods using beekeeping with little investment and expertise (Bradbear 2003; Jacobs et al. 2006). Beekeepers can support their livelihood and generate income by producing and selling colonies, honey, and other products (Jacobs et al. 2006; Teweldemedhn and Yayneshet 2014a; Tavonga Mazorodze 2015; Jones et al. 2016) depending on the experience, interest, and other prevailing factors.

In this study, the number of colony buyers who have beekeeping experience was significantly lower than that of sellers, which indicate an increasing interest of beginners into honey production than colony reproduction, although most of the market actors were experienced beekeepers in general (Table I). Traditional beekeepers skilled in colony production using reproductive swarming were the main suppliers of colonies for the relatively less experienced buyers who aim to start, re-stock or expand their colonies that are primarily used for honey production. A previous report indicated that reproductive swarming was the main source of colony for some market places in Tigray such as Nebelet, while others (e.g., Maikinetal) rely on trapping feral colonies (Teweldemedhn and Yayneshet 2014a). Feral colonies can be trapped using hives baited with different substances (Papachristoforou et al. 2013), but success depends on abundance. The density of feral colonies is higher in undisturbed habitats (Hinson et al. 2015) and rural areas that are covered with tick trunked woods (Oleksa et al. 2013). Tigray is characterized by high density of human population and fragmented landholding, which is worse in the highlands of the region.

Therefore, the market involved exchange of colonies between different AEZs covering broad areas. These include three districts of origin and eight districts of destination, which extend up to 135 km aerial distance with a significant difference between the sellers and buyers in spatial and ecological distributions. The colonies were originated mainly from highland areas of two districts (Figure 1a). These areas are characterized by lower temperature and flora which led the beekeepers to focus on market-oriented colony production. In contrast, the buyers are widely distributed throughout eight districts (Figure 1b) and are aimed to produce honey. Overall, the sellers and buyers were specialized in swarm and honey production, respectively, based on the potential of their local areas. As a result, there was a one-way flow of honey bee colonies from few colder and drier mountains to wide areas of higher honey production potential as previously reported (Nuru 2002; Teweldemedhn and Yayneshet 2014b). Experiences show that such apicultural activities cause reduction of genetic diversity (Meixner et al. 2010; De la Rúa et al. 2013; Coroian et al. 2014; Espregueira Themudo et al. 2020) and erode adaptation to local conditions (Büchler et al. 2014). Other challenges of marketing and transportation include concerns on queen quality (fertility), and safety of colonies (death due to stress), and desertion of worker bees in the market (Teweldemedhn and Yayneshet 2014a).

Consequently, the transportation of colonies across AEZs and areas in Tigray eroded genetic differentiations which may threaten the adaptation potential of the honey bees (Table III). Similarly, previously conducted population studies showed that Ethiopian honey bees represent one subspecies (Meixner et al. 2011) characterized by a high rate of gene flow, and reduced morphological and genetic differentiations (Hailu et al. 2021). However, there was a conserved signature of genetic adaptation in a small area (Werieleke district), which consists of extensive land-use, where beekeepers locally collect colonies by trapping (Teweldemedhn and Yayneshet 2014b) unlike other districts in the region. As a result, diverged genetic differentiation between highland and lowland honey bees of Werieleke (FST = 0.22, Nm = 2.23) was identified by an allelic length polymorphism (Table III) within the genomic region (denoted r7-frag) of the gene octopamine receptor beta-2R (LOC412896), which modulates responses to sucrose (Blenau et al. 2002), odors (Hammer and Menzel 1998), visuals (Erber 1995), nursing (Behrends and Scheiner 2012), temperature (Armstrong and Robertson 2006; Cook et al. 2017), and hypoxia (Money et al. 2016) in insects. It is important to note that no market actor from Werieleke was encountered during the colony market survey in Enticho despite its proximity. In contrast, no differentiation could be detected between two areas of markedly different elevations (Mugulat and Adikebero) in one of the main colony producer and supplier districts (Ganta-Afeshum) in Tigray (Table III). This was due to a high level of gene flow in Ganta-Afeshum (Nm = 17.87) as opposed to Werieleke (Hailu et al. 2021). The genetic marker r7-frag selected for this study was identified to be associated with elevational adaptation in east African honey bees (Wallberg et al. 2017).

Highland beekeepers interviewed in the market survey were specialized in colony multiplication and selling because they perceived that their areas are too cold and less suitable for honey production. According to these beekeepers, colony reproduction and marketing was more viable than honey production in the highland AEZs. Whereas, the buyers were interested to purchase colonies in the central market over other alternatives including trapping swarms, buying in their villages or reproducing their own stock (Table II). This was related to their preferences for color and AEZs of origin of the colonies. Black honey bees originated from colder highland areas were perceived by the buyers to be easily adaptable in broader AEZs and more defensive than the lighter colored bees. These perceptions led to separate production of colonies and honey in the colder highland and warmer lowland AEZs, respectively. East African highland honey bees (A. m. monticola) were reported to be more friendly than their neighboring lowland honey bee populations (Ruttner 1988), in contrast to the perception of the respondents in this survey on A. m. simensis (Meixner et al. 2011; Hailu et al. 2020). Moreover, honey yield of colonies is less heritable (Brascamp et al. 2016); largely depends on environmental factors including management. A field experiment will have to validate the beekeepers’ claims and assumptions regarding the behavior, performance, and adaptation. The beekeeping research and extension in the region appeared to focus on enhancing production and productivity (Figure 3) through training and provision of technical as well as financial inputs for both honey and colony producers. However, there is no evidence that apicultural extension efforts contributed to limiting honey bee colony transportation and re-distributions through the marketing. Apart from technology transfer, agricultural research and extension should meet new demands, food security, and rural poverty alleviation (Waithaka 2001). Global experience on apicultural research shows that the focus has been evolving from improving productivity and temperament (Adam 1987) to vitality and local adaptation (Blacquière et al. 2019; Büchler et al. 2020); gearing to address massive challenges of V. destructor (Conte et al. 2020) and genetic erosion (Espregueira Themudo et al. 2020). Traditionally, beekeepers in Tigray select colonies based on colony size (strength), color, gentleness, honey yield, etc. However, the apicultural research in Ethiopia generally remained in its infant stage, and there is no feasible breeding initiative to address local challenges of sustainability in the sector, to be elaborated in a following piece.

In conclusion, the regional apiculture showed substantial progress in honey production and productivity through various development interventions, which increased the overall colony management but did not make a significant contribution in shaping colony production and marketing behavior of the beekeepers. That is, access to beekeeping extension service, type of service received and the provider organization did not influence the market actors’ roles. Lack of access to colonies at local areas with reasonable prices, beekeepers’ perception and skill limitations are the main factors driving for the marketing and transportation of colonies by reproducing in a few highland AEZs. This has caused an extensive level of gene flow and impacted the honey bee genetic diversity. Therefore, apicultural research and extension in the region should consider ensuring sustainable development of the sub-sector by providing relevant support to the beekeepers. Beekeepers in the highland AEZs need to be supported in maintaining thermal stability of their beehives and improving honey bee flora in order to be able to produce honey and other products instead of current practices of market-oriented colony production. Similarly, improving the skills on swarm production and trapping can help the buyers to create local access to colonies. Performance evaluation and a sustainable breeding strategy to meet the beekeepers’ objectives accompanied with raising awareness on risks of introducing honey bees from different AEZs can contribute to reducing transportation of colonies across the region.

Data availability

Additional data can be requested from the corresponding author, TGH.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Abebe W, Puskur R, Karippai RS (2008) Adopting improved box hive in Atsbi Wemberta district of Eastern Zone, Tigray Region: determinants and financial benefits. Improving Productivity and Market Success of Ethiopian Farmers. IPMS Work. Pap. (10)

Adam (1987) Breeding the honeybee: a contribution to the science of bee-breeding. First. Mytholmroyd: Southern Bee Books

Armstrong GAB, Robertson RM (2006) A Role for Octopamine in Coordinating Thermoprotection of an Insect Nervous System 31:149–158

Bahiru B, Mehari T, Ashenafi M (2001) Chemical and nutritional properties of `tej’, an indigenous Ethiopian honey wine: variations within and between production units. J Food Technol Africa 6(3)

Behrends A, Scheiner R (2012) Octopamine improves learning in newly emerged bees but not in old foragers. 1076–83

Blacquière T, Boot W, Calis J, Moro A, Neumann P, Panziera D (2019) Darwinian black box selection for resistance to settled invasive Varroa destructor parasites in honey bees. Biol Invasions 21(8):2519–2528

Blenau W, Scheiner R, Plu S (2002) Behavioural pharmacology of octopamine, tyramine and dopamine in honey bees. 136:545–53

Bogale S (2009) Indigenous knowledge and its relevance for sustainable beekeeping development. Livest Res Rural Dev 21(11)

Bradbear N (2003) Beekeeping and sustainable livelihood. Diversification.

Brascamp EW, Willam A, Boigenzahn C, Bijma P, Veerkamp RF (2016) Heritabilities and genetic correlations for honey yield, gentleness, calmness and swarming behaviour in Austrian honey bees. Apidologie 47(6):739–748

Büchler R, Costa C, Hatjina F, Andonov S, Meixner MD et al (2014) The influence of genetic origin and its interaction with environmental effects on the survival of Apis Mellifera L. Colonies in Europe J Apic Res 53(2):205–214

Büchler R, Kovačić M, Buchegger M, Puškadija Z, Hoppe A, Brascamp EW (2020) Evaluation of traits for the selection of Apis mellifera for resistance against Varroa destructor. Insects 11(9):1–20

Calderón RA, Van Veen JW, Sommeijer MJ, Sanchez LA, Sommeijer MJ (2010) Reproductive biology of Varroa destructor in Africanized honey bees (Apis mellifera). Exp Appl Acarol 50:281–297

Cook CN, Brent CS, Breed MD (2017) Octopamine and tyramine modulate the thermoregulatory fanning response in honey bees (Apis mellifera). J Exp Biol 220(10):1925–1930

Coroian CO, Muñoz I, Schlüns EA, Paniti-Teleky OR, Erler S et al (2014) Climate rather than geography separates two European honeybee subspecies. Mol Ecol 23(9)

CSA (2004) Agricultural sample survey 2010/11 [2003 E.C.], Report on Livestock and Livestock Characteristics

CSA (2021) Agency agricultural sample survey 2020/21 [2013 E.C.] Report on Livestock and Livestock Characteristics

CSA (2020) Central statistical authority of Ethiopia: report on livestock and livestock characteristics (Private Peasant Holdings)

De La Rúa P, Jaffé R, Olio RD, Muñoz I, Serrano J (2009) Biodiversity, conservation and current threats to European honeybees. Apidologie 40(3):263–284

De la Rúa P, Jaffé R, Muñoz I, Serrano J, Moritz RF, Kraus FB (2013) Conserving genetic diversity in the honeybee: comments on Harpur et al. (2012). Mol Ecol 22(12):3208–10

Dessalegn Y, Hoekstra D, Berhe K, Derso T, Mehari Y (2010) Smallholder apiculture development in Bure, Ethiopia: experiences from IPMS project interventions

Dhyani A, Semwal KC, Gebrekidan Y, Yonas M, Yadav VK, Chaturvedi P (2019) Ethnobotanical knowledge and socioeconomic potential of honey wine in the horn of Africa. Indian J Tradit Knowl 18(2):299–303

Erber EK (1995) The modulatory effects of serotonin and octopamine in the visual system of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.). J Comp Physiol A 176:119–29

Espregueira Themudo G, Rey-Iglesia A, Robles Tascón L, Bruun Jensen A, da Fonseca RR, Campos PF (2020) Declining genetic diversity of European honeybees along the twentieth century. Sci Rep 10(1):1–12

FAO (2018) Food and agriculture data. Retrieved http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QL

FAOSTAT (2021) Food and agriculture data. Food Agric Organ United Nations. Retrieved September 20, 2021 http://www.fao.org/faostat/en

Federal Parliament (2009) A proclamation to provide for apiculture resources development and protection. Negarit Gazeta 5117–26

Gebretinsae and Stellmacher (2018) The role of cooperative beekeeping in hillside rehabilitation areas for rural livelihood improvement in northern Ethiopia. pp. 0–335 in The Role of Bees in Food Production, edited by Lukas Garibaldi et al. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Apiculture Board

Geeraert L, Aerts R, Berecha G, Daba G, De Fruyt N, D’hollander J, Helsen K, Stynen H, Honnay O (2020) Effects of landscape composition on bee communities and coffee pollination in Coffea arabica production forests in southwestern Ethiopia. Agric Ecosyst Environ 288(September 2019)

Girma and Gardebroek (2015) The impact of contracts on organic honey producers’ incomes insouthwestern Ethiopia. For Policy Econ 50:259–268

Gratzer K, Wakjira K, Fiedler S, Brodschneider R (2021) Challenges and perspectives for beekeeping in Ethiopia. Rev Agron Sustain Dev 41

Hailu TG, D’Alvise P, Hasselmann M (2021) Disentangling Ethiopian honey bee (Apis mellifera) populations based on standard morphometric and genetic analyses. Insects 12(3):193

Hailu TG, D’ALvise P, Tofilski A, Fuchs S, Greiling J, Rosenkranz P, Hasselmann MH (2020) Insights into Ethiopian honey bee diversity based on wing geomorphometric and mitochondrial DNA analyses. Apidologie 51(6):1182–1198

Hailu TG, Tesfay Y (2012) Modern and traditional beekeeping: constraints and opportunities for promotion in highland, midland and lowland agro-ecologies. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, Saarbrücken

Hammer M, Menzel R (1998) Multiple sites of associative odor learning as revealed by local brain microinjections of octopamine in honeybees. Learn Mem 5(1):146–156

Hinson EM, Duncan M, Lim J, Arundel J, Oldroyd BP (2015) The density of feral honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies in South East Australia is greater in undisturbed than in disturbed habitats. Apidologie 46(3):403–413

IPBES (2016) The assessment report of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services on pollinators, pollination and food production. S.G. Potts, V. L. Imperatriz-Fonseca, and H. T. Ngo (Eds).

Jacobs FJ, Simoens C, de Graaf DC, Deckers J (2006) Scope for non-wood forest products income generation from rehabilitation areas: focus on beekeeping. J Drylands 1(2):171–185

Jones L, Norton L, Austin Z, Browne AL, Donovan D et al (2016) Economic valuation of pollination services: review of methods. ACI Struct J 12(January):2016

Langstroth LL (1852) Beehive. (9)

Le Conte Y, Meixner MD, Brandt A, Carreck NL, Costa C, Mondet F, Büchler R (2020) Geographical distribution and selection of European honey bees resistant to Varroa destructor

Loftus JC, Smith ML, Seeley TD (2016) How honey bee colonies survive in the wild: testing the importance of small nests and frequent swarming. PLoS ONE 11(3):1–11

Meixner MD, Costa C, Kryger P, Hatjina F, Bouga M, Ivanova E, Büchler R (2010) Conserving diversity and vitality for honey bee breeding conserving diversity and vitality for honey bee breeding. J Apic Res 49(1):85–92

Meixner MD, Leta MA, Koeniger N, Fuchs S (2011) The honey bees of Ethiopia represent a new subspecies of Apis mellifera-Apis mellifera simensis n. ssp. Apidologie 42(3):425–37

Money TGA, Sproule MKJ, Cross KP, Robertson XRM (2016) Octopamine stabilizes conduction reliability of an unmyelinated axon during hypoxic stress. J Neurophysiol 116:949–959

Nuru A (2002) Selling honeybee colonies as a source of income for subsistence beekeepers. Bees Dev 64

Oleksa A, Gawroński R, Tofilski A (2013) Rural avenues as a refuge for feral honey bee population. J Insect Conserv 17(3):465–472

Papachristoforou A, Rortais A, Bouga M, Arnold G, Garnery L (2013) Genetic characterization of the cyprian honey bee (Apis mellifera cypria) based on microsatellites and mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms. J Apic Sci

Porto RG, de Almeida RF, Cruz-Neto O, Tabarelli M, Viana BF, Peres CA, Lopes AV (2020) Pollination ecosystem services: a comprehensive review of economic values, research funding and policy actions. Food Secur 12(6):1425–1442

Ruttner F (1988) Biogeography and taxonomy of honey bees. Springer-Verlag, Berlin

Tarekegn K, Ayele A (2020) Impact of improved beehives technology adoption on honey production efficiency: empirical evidence from Southern Ethiopia. Agric Food Secur 9(1):1–13

Tavonga Mazorodze B (2015) The contribution of apiculture towards rural income in Honde Valley Zimbabwe. Natl Capacit Build Strateg Sustain Dev Poverty Alleviation Conf Am Univ Emirates, Dubai 2014:1–10

Teweldemedhn G, Yayneshet T (2014a) Honeybee colony marketing and its implications for queen rearing and beekeeping development in Tigray. Ethiopia Int J Livest Prod 5(7):117–128

Teweldemedhn G, Yayneshet T (2014b) Honeybee colony marketing practices in Werieleke district of the Tigray Region. Ethiopia Bee World 91(2):30–35

Waithaka M (2001) Agricultural extension and rural development: breaking out of traditions

Wallberg A, Schöning C, Webster MT, Hasselmann M (2017) Two extended haplotype blocks are associated with adaptation to high altitude habitats in East African honey bees. PloS Genet 13(5):e1006792

Wright S (1951) The Genetic Structure of Populations Eugenics 15:323–354

Yirga and Gidey MT (2010) Participatory technology and constraints assessment to improve the livelihood of beekeepers in Tigray Region, northern Ethiopia. Momona Ethiop J Sci 2(1):76–92

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Hadgu Hishe for producing the location maps (Figure 1c, d), and the interviewees for collaborating during the colony market survey (July–Aug 2019) in Enticho town of Tigray, northern Ethiopia. TGH is a scholarship holder of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), Funding programme/-ID 57299294.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TGH acquired and analyzed the data; all authors contributed in the conception and design of the research, and manuscript drafting and revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from the interviewees who participated in the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Manuscript editor: David Tarpy

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hailu, T.G., Rosenkranz, P. & Hasselmann, M. Rapid transformation of traditional beekeeping and colony marketing erode genetic differentiation in Apis mellifera simensis, Ethiopia. Apidologie 53, 45 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-022-00957-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-022-00957-y