Abstract

The attractiveness of mineral investments across countries and regions worldwide can be judged through various measures, each with its strengths and weaknesses. The purpose of this paper is to scrutinize the Fraser Institute’s ranking of mining jurisdictions, which builds on eliciting the perceptions of industry representatives around the world through an annual survey. The analysis takes stock in the growing scholarship on country performance indicators and concludes that due to the low response rate and the lack of clear definitions of some of the underlying concepts (e.g., political stability), there are reasons to question both the reliability and the validity of this survey. There could also exist incentives among exploration companies to “game” the rankings. For these reasons, the ranking outcomes do not constitute a meaningful scorecard that countries can employ to improve their mining-related policies. However, despite these deficiencies, the Fraser Institute’s survey often enjoys relatively uncritical media attention. It even sets in motion a political “rankings game” in which the mining companies, governments, and other organized groups choose to participate. There is an urgent need for a more reliable and unbiased survey approach, including the consideration of alternative—complementing—measures for assessing investment attractiveness in the mining industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Countries that wish to attract private investors to identify and exploit their mineral resources must compete for the available investment and expertise. In this context, the relative ranking of mining jurisdictions (i.e., countries, provinces, states) can be relevant from a competitiveness point of view. For each jurisdiction, there is no absolute benchmark to aim for in terms of, for instance, policy design and regulations; what matters is how the jurisdiction performs compared to others. This paper provides a critical scrutiny of the most visible and widely quoted ranking of countries in terms of their attractiveness for mineral investment, the Fraser Institute’s annual mining survey.

Each year, the Canadian-based think-tank calls on mining executives from around the world to assess the attractiveness of global mining jurisdictions in terms of both mineral potential and a broad range of mining policies and regulations (see Mejía and Aliakbari (2023) for the 2022 ranking). The results from this annual survey are regularly quoted in—not least—business media but also in various political arenas (see below for examples). The final ranking is typically taken at face value and presented in the context of an international popularity contest.Footnote 1

Previous research shows that both geological potential (mineral endowments) and government policy—e.g., mineral taxation and regulatory regimes, quality of government and public service as well as political stability—explain why some countries and regions attract more investments to sustain exploration and mining activities than others (Vásquez and Prialé Zevallos 2021; Khindanova 2011, 2015; Jara 2017; Tole and Koop 2011; Otto 2006, Peck et al. 1992). This thus supports the Fraser Institute’s focus on these two factors as the primary drivers of investments in the global mining industry. Still, most previous work builds on data on actual mining investments, e.g., exploration expenditures, rather than survey data, thus relying on the actual behavior of market participants rather than on any self-reported perceptions. This raises questions about the drawbacks, e.g., lack of reliability and validity, of the survey approach, but also about the pros and cons of alternative measures of investment attractiveness (Jara et al. 2008) as well as of global benchmarking initiatives in general (Doshi et al. 2019).

The objective of the paper is to scrutinize the Fraser Institute’s ranking of mining jurisdictions, which builds on eliciting the perceptions of industry representatives through an annual survey. The paper takes stock in the growing scholarship on country performance indicators and global benchmarking (e.g., Beaumont and Towns 2021; Doshi et al. 2019; Kelley and Simmons 2019), which has highlighted several difficulties with such cross-country comparisons. These include concerns about data reliability and validity, negative side-effects of the ranking (e.g., attempts to influence the design and the results of the survey), and the fact that rankings tend to downplay difficult political issues and trade-offs. However, despite these shortcomings, there are often vested economic interests and social relations that tend to maintain a continued interest in the various country performance indicators (Beaumont and Towns 2021).

Our assessment builds on a scrutiny of the annual reports of the Fraser Institute and focuses on both methodological choices and the data reported (with a focus on the published reports from the last two decades). We also consult several articles in various digital and printed business media outlets. These provide empirical illustrations of how the findings of the mining survey are covered, commented on, and employed by various actors (e.g., mining companies, industry organizations, government agencies, and other organized groups). Finally, the assessment also builds on reflections on the Fraser Institute’s mining survey received in 17 personal interviews conducted during the spring of 2023.

The interviewees represent mining organizations, junior and larger mining companies, public authorities and individual commentators, and analysts. These individuals were asked about their views on the Fraser Institute’s annual mining survey—its strengths and its weaknesses. The ambition with these interviews was not to provide a representative sample of the views of these groups, but rather to ensure that important aspects of the survey were not overlooked in the assessment. Moreover, among these respondents, we find both those who are critical of this survey (e.g., arguing it to “present biased results” and being “open to misuse”) as well as those who express that it is reasonably useful and valid (e.g., expressing that the survey responses tend to “reflect the reality” and “something of the underlying situation in a country”).

By achieving the above, the paper contributes to the existing literature by (a) providing an in-depth scrutiny of the most influential survey-based approach to assessing mining investment attractiveness worldwide, thereby also adding to the scholarly debate about the pros and cons of various indicators of the global investment climate in this industry (Jara et al. 2008); and (b) adding yet another case study of how country performance indicators are generated and used.

The paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, we briefly review existing research on the practice and politics of global benchmarking, while a following section introduces the Fraser Institute’s annual mining survey and how this results in a ranking of mining jurisdictions in the world. The paper then scrutinizes various aspects of this survey, i.e., addressing concerns about the reliability and the validity of the results, but also how these results, despite any concerns, inspire a “political rankings game” in which governments, mining companies and executives, and additional organized groups appear keen to participate. The main findings are discussed in a separate section, which also comments on alternative measures of investment attractiveness. The paper ends with some concluding remarks and avenues for future research.

The practice and politics of global benchmarking

Over the last decades, the number of international rankings and country performance indicators has increased rapidly (Kelley and Simmons 2019). Such indicators could provide interesting cross-country evaluations, a better understanding of best practices (e.g., in terms of government regulations, ease of doing business), and in this way supporting evidence-based policymaking as well as increasing the accountability of public officials. Previous research shows how country performance indicators, e.g., the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business (EBI) index (Doshi et al. 2019), have induced policy reforms and shaped the perceptions of investment opportunities.

At the same time, though, there is also growing research raising concerns about methodological weaknesses and various problematic side effects of the development and practice of country performance indicators, including the depoliticization of the important underlying issues (e.g., Broome et al. 2018; Freistein 2016; Van der Vleuten and Verloo 2012). Specifically, the existing literature has contested the practice of country performance indicators on two central grounds (Beaumont and Towns 2021).

First, country performance indicators are often criticized for lacking methodological veracity (e.g., Firchow and Ginty 2017). While the organizations that produce these indicators market them as “score cards” that governments can employ to improve policy, there may be concerns about both the reliability and validity of these scores. Clearly, in the case of indicators that are based on surveys, the reliability could be questioned if the response rate is low and/or if there is evidence of sample selection and/or response bias. Equally important is the lack of validity of various indicators. Most country performance indicators represent attempts to operationalize—often expediently rather than rigorously—concepts that are far from straightforward, e.g., equality, freedom, investment climate, and democracy (e.g., Broome and Quirk 2015).

This also involves difficulties in separating related concepts from each other. For instance, in this paper, we observe that one question in the Fraser Institute’s annual mining survey is an attempt to measure the “pure” geological potential of the different jurisdictions, in other words ignoring existing institutions and policies (see further next section). Nevertheless, the responses given may not necessarily reflect this ambition; there is a risk that company representatives do—consciously or unconsciously—incorporate also other features of geological attractiveness in their responses, including policy and regulations (see also Keen 2015).

Moreover, the reliability and validity of country performance indicators can also be influenced by the presence of incentives to manipulate and “game” the rankings (Cooley 2015). This can occur in several ways, e.g., through directly lobbying the organization responsible for producing the indicator (e.g., arguing for alternative measures) or by providing answers to surveys that do not truly reflect the perceptions of the respondent. In this paper, we emphasize that exploration companies may have incentives to exaggerate the mining investment climate in jurisdictions in which they are currently pursuing exploration activities. There could also be “perverse” effects, such as if governments become incentivized to assign too much weight on the specific measures established by the indicators (Beaumont and Towns 2021).

The latter is related to a second strand of critique of country performance indicators. Most indicators—at least implicitly—build on some normative theory of what is good and bad, and this in turn implies that they do typically not represent objective measurements. Instead, such indicators tend to be political and power-laden (e.g., O’Neil 2017). One example is the above-mentioned EDB index, which has been criticized, e.g., by the International Labor Organization (ILO), for a strong deregulatory bias (Doshi et al. 2019).Footnote 2 Country performance indicators tend to simplify a complex regulatory reality. Scott and Light (2004) note that these indicators sweep “vast realms of legitimate public debate out of the public sphere,” thus hiding “vital politics in a series of conventions, measures, and assumptions that escape public scrutiny and dispute” (p. 199). This implies a democratic deficit, which will be particularly worrying in those cases where the indicators are used as the foundations for political reforms (Broome et al. 2018).

However, despite such deficiencies and the critique raised, there is often widespread quotes to—and reliance on—country performance indicators. Beaumont and Towns (2021) contend that this paradox must be understood based on the complex of relations among various types of actors. First, we have the producers of the indicators; these organizations, including the Fraser Institute, specify the rules of the game and essentially establish a “scorecard” upon which the country rankings can be generated (Kelley 2017). In this way, these producers act as referees while at the same time also identifying the players of the game that are government agencies inclined to play the game and treating the rankings provided as authoritative information. Even though governments do not enjoy the game and agree with its (often implicit) rules, they may nonetheless wish to acquire the economic, social, and political rewards from competing and thereby avoid the possible drawbacks of receiving a low rank (Beaumont and Towns 2021).

Furthermore, another group of players is the audience, which is interested in the game and the outcomes of it Kelley and Simmons (2019). This includes, for instance, industry representatives, non-governmental organizations, opposition parties, and members of the public who are keen to employ the rankings to pass judgements on policies and even on single politicians, as well as exert pressure on the government to change its policies. Such actors can generate attention and legitimacy for a certain indicator and thus operate as a channel through which this indicator (and its founder) could exert pressure on governments. In other words, external validation or criticism from a credible organization can become part of a strategy to bolster a broad coalition for policy reform.

Beaumont and Towns (2021) argue that since audiences need to be kept interested in the country performance indicators, the quality of a certain indicator will be influenced by the preferences of the interested actors, i.e., “the degree to which an audience demands methodological rigorous data is capable of understanding and interpreting it critically and cares about whether it is affected by any counter-productive effects of the competition it inspires” (p. 1479). In other words, there will not necessarily be any self-reinforcing mechanisms that help improve—or even maintain—the quality of the methods used to generate country performance indicators.

The Fraser Institute’s annual survey of mining companies

The Fraser Institute, established in 1974, is today one of the most influential think tanks in the world. The headquarter is in Vancouver, Canada. An important objective from start has been to provide a home for research aimed at promoting alternative, free market-oriented economic policy measures on a range of issues. The Institute has a conservative agenda and with a strong emphasis on small government and individual freedom. Its most well-known publication is the annual so-called Human Freedom Index (published jointly with the Cato Institute). This index constitutes a broad measure of human freedom, primarily understood as the absence of coercive constraints (Vásquez et al. 2022).

Since 1997, the Fraser Institute has conducted an annual survey of officials in the global mining and exploration industry to assess how mineral endowments and government policy, such as taxation and regulations, influence mining exploration investment. A voluntary opinion survey is sent to officers, managers, and additional experts with mining exploration and development companies, and their advisors. The survey responses are used to calculate an overall Investment Attractiveness Index (IAI) for each jurisdiction based on the respondents’ perception of both the geological potential (60 percent weight) and government policy (40 percent).

Specifically, the IAI is based on two separate indexes. First, the so-called Best Practices Mineral Potential Index (BPMPI) shows the mineral (geological) potential of various jurisdictions, “assuming their policies are based on “best practices,” i.e., world class regulatory environment, highly competitive taxation, no political risk or uncertainty, and a fully stable mining regime” (Yunis and Aliakbari 2022, p. 20). In other words, this index attempts to assess the perceptions about the “pure” mineral potential of the various jurisdictions.

In the survey, the respondents are asked to choose among five alternatives, i.e., whether the geological potential of each jurisdiction (a) encourages exploration investment, (b) is not a deterrent to exploration investment, (c) is a mild deterrent to exploration investment, (d) is a strong deterrent to exploration investment, or whether it implies that firms (e) cannot pursue exploration investment in the region due to this factor. The BPMPI ranks the jurisdictions based on which jurisdiction’s geology “encourages exploration investment” or is “not a deterrent to investment” and with half the weight given to the latter response. For instance, if 47 percent of the respondents have stated that the geological potential encourages investment and 28 percent have ticked the not-a-deterrent alternative, the BPMPI score becomes 61.

Second, the so-called Policy Perception Index (PPI) is a composite index that attempts to assess the opinions of managers and executives on the effects of policies in jurisdictions with which they are familiar. The Fraser mining survey includes numerous policy-related questions—i.e., regarding uncertainty about the administration, interpretation, and enforcement of the existing regulations; environmental regulations; regulatory duplication and inconsistencies; taxation; uncertainty concerning various land claims and protected areas; infrastructure; socioeconomic agreements; political stability; labor issues; geological database; and security—and all of these are employed in the calculation of the PPI. A total of 15 policy factors are addressed, and these have remained unchanged since the 2013 mining survey.Footnote 3

For each of these factors, the respondents are asked to select one of the above-mentioned five response alternatives that best describes each jurisdiction with which they are familiar. The score for each policy factor is based on all the five response categories and on how far each jurisdiction’s score is from the average. This score is then standardized: the average response is subtracted from each jurisdiction’s score on each of the policy factors and then divided by the standard deviation. The scores for each of the 15 policy variables are then added up to generate a final, standardized PPI score, which is normalized and takes a value between zero (0) and 100 (e.g., Yunis and Aliakbari 2022).

The authors of the annual mining survey emphasize that the results from the survey can improve decision-making for several categories of actors. For instance, in the 2021 report they remark:

Our purpose is to create a ‘report card’ that governments can use to improve their mining-related public policy to attract investment in their mining sector to better their economic productivity and employment. Others in the mining sector, investment sector, academia, and the media also may find the survey useful for evaluating potential investment decisions, or for assessing various risk factors in jurisdictions of interest (Mejía and Aliakbari 2023, p. 3).

It is frequently claimed that the results from the survey are indeed used for such purposes (e.g., PressProgress 2014). Clearly, though, it is difficult to provide evidence of a causal relationship between the results reported for a specific jurisdiction in the Fraser survey and any subsequent policy reforms in that same region. However, it is evident how the results from the survey are widely reported in the media, not least various business media outlets, and then used by industry to lobby for policy changes. A few examples of reactions from national mining organizations following the launch of the 2022 survey can demonstrate this point (see additional examples below):

-

Due to the low ranking of South Africa (57 out of 62 in terms of IAI), the Minerals Council of South Africa announced that it will meet with the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy to discuss the reasons behind the country’s low ranking. The Council’s CEO expresses that he will engage with government on each of the 15 policy factors of the survey to propose potential solutions (Arnoldi 2023).

-

In Papua New Guinea (PNG), the country’s low ranking (54 out of 62 in terms of IAI) has led the PNG Chamber of Mines and Petroleum to call for an urgent dialogue with the national government to address problems related to regulatory uncertainty and the taxation policy (Nangoi 2023).

-

In the 2022 survey, Namibia was ranked 38 in terms of its IAI, and following the launch of this outcome, the CEO of the Chamber of Mines of Namibia has expressed that he is confident that the government will address the policy concerns cited in the report in the ongoing Minerals Bill review (Chamber of Mines of Namibia 2023).

-

Even though the Fraser survey confirms that the Australian jurisdictions continue to be perceived as highly attractive from an investment point-of-view, the Mineral Council of Australia used the launch of the survey results as an opportunity to remark that there is a need to overhaul several government processes and policies (Southway 2023).

Typically, the results from the Fraser Institute’s mining survey are often reported at face value. This is also the case in various policy evaluations relying on the rankings, i.e., with no analysis of—and/or remarks on—the reliability and validity of the rankings (e.g., Oyunchimeg 2016; Moffatt 2016). As shown below, though, there are reasons to question the quality of the survey (see also Casey, 2022; Fulp 2018; Keen 2015). This suggests that there is a clear risk that a skewed assessment of the perceptions of mining executives could have real-life policy impacts.

Evaluation

Our assessment of the Fraser Institute’s mining survey is divided into three main parts. In the first sub-section, we elaborate on one of the survey’s key problems, the low response rate. This is reason to question the reliability of the results, which will not provide a representative picture of the perceptions of the global mining industry. However, the concerns raised over the survey also relates to the validity of the results, i.e., the extent to which the survey has measured the concepts it is intended to measure. This is commented on, and exemplified, in a second sub-section. Finally, in a third sub-section, we address how the survey can provide fuel for a political game among various actor groups that have an interest in the future of the mining industry.

A low and declining response rate

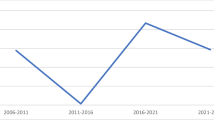

Over the last two decades, the Fraser Institute has sent out between about 2000 and 5000 surveys (in 2022, the total was 1966). Fig. 1 displays the total number of responses received as well as the total response rate (including partly completed surveys). Since 2011, the total number of responses has fallen from around 500–700 to only 180 in 2022, and the response rate has gone down from around 17–18 percent to below 10 percent over this period.Footnote 4

The low response rate has consequences for the number of jurisdictions for which rankings can be reported. In 2011, results were reported for 109 jurisdictions while the corresponding number in 2022 was only 62. The minimum threshold for inclusion has been five responses, and (since 2014), the Institute notes which jurisdictions have between 5 and 9 responses. In the 2022 survey, a total of 86 jurisdictions had to be left out of the final report, and out of the 62 included ones, the scores, and the rankings for as many as 25 jurisdictions (40 percent) were based on only 5–9 responses (Mejía and Aliakbari 2023).Footnote 5

There is thus a substantial risk that the annual survey has become nothing more than an opinion poll from a small group of individuals that are not representative of the global mining industry. The Fraser Institute claims that the survey is intended to “capture the opinions of managers and executives about the level of investment barriers in jurisdictions with which their companies are familiar” (Yunis and Aliakbari 2022, p. 6, emphasis added). However, the respondents’ knowledge about mineral potential and policy factors in each of the jurisdictions on which they choose to share their views is self-reported; they need not have ever worked or done business in the region. Given the very low number of responses for a substantial share of the jurisdictions, there is therefore an apparent risk that the survey is heavily skewed towards executives with limited knowledge of the jurisdictions outside of their own project areas (see also Fulp 2018).

One relevant example is Zambia, which in the 2022 survey only received between 5 and 9 responses. Mining for Zambia (2023) notes that despite a significant increase in investments flowing into the Zambian mining industry during the year, the 2022 survey from the Fraser Institute reported the country as now being less attractive to investors (ranked in position 58 out of 62 in terms of the IAI). This begs the question who the respondents to the survey in fact were, and what their backgrounds are.Footnote 6 Moreover, Ryan (2022) reports on the low ranking of South Africa in the 2021 survey and remarks that several members of the country’s Minerals Council were not invited to participate, and those that were invited did not participate.

Commentators have remarked how the survey tends to have a bias towards presidents and vice-presidents of mainly exploration companies (e.g., Keen 2015) in primarily Canada, the USA, and Australia (e.g., Vale and Herrmann 2004). Others have pointed out that—at least in the past—there has been a predominance of junior companies, something which begs the questions whether too much weight has then been afforded to the attitudes of gold exploration companies, and, if so, to what extent such a focus has resulted in a representative picture of the entire mining industry (Vale and Herrmann 2004). The perceptions of junior companies solely exploring for gold can differ substantially from a larger company with a robust budget and diversified focus. There is also the issue of the level of responsibility of the professional answering the survey, which, with its focus on exploration, development, and mining, demands different specialized insights. Moreover, the views of financial investors are not assessed in the survey.

In our interviews, several mining professionals confirmed that they have very few ideas about who the often-small group of respondents for a specific country are (“strange—who do they ask?”). In Sweden, our interviews confirmed that none of the existing mining companies had answered the survey during the last years. Some of these also expressed concerns about the reliability of the results: they are “biased” and “skewed and dependent on entries from those who have shown initiative and/or received an invitation to complete the survey.” Finally, a few of the mining organizations approached emphasized that they had tried in the past to develop a dialogue with the Institute to increase the number of responses received and to, for instance, make sure that the mining companies that spend most of the exploration funds are also given the opportunity to respond. Still, they remarked, neither of these organizations succeeded in establishing a stable contact with the Institute.

The validity of the survey

In this sub-section, we address some aspects of the validity of the mining survey. In a first step, some remarks on the outcome of the IAI rankings are provided, then turning to the two central components of this overall ranking: geological potential and policy.

One key topic of concern relating to the validity of the annual mining rankings provided by the Fraser Institute has been the fact that the rankings of many jurisdictions often change radically from one year to another (e.g., Keen 2015). Clearly, at the top, the results for the period 2011–2022 are relatively stable. Jurisdictions such as, e.g., Nevada, Western Australia, Saskatchewan, and Quebec are (more or less) consistently among the top ten in terms of overall investment attractiveness. This is also noted by a few of the interviewees, e.g., remarking that the responses “are not perfect but to some extent, they reflect the reality” and that “the Fraser survey reflects something of the underlying situation in a country.”

Still, we also find that during this period, a total of 28 jurisdictions have been ranked among the top ten at least once, but, at the same time, as many as ten of these have also at some point been ranked in the bottom half of the reported sample. Furthermore, 16 out of these 28 jurisdictions have witnessed a change in their overall investment attractiveness ranking by 15 spots or more from one year to another.

Evidently, the fact that the rankings of jurisdictions change over time is not a problem per se; the whole idea of generating performance indicators that allow country rankings is to be able to observe differences across jurisdictions as well as over time. Nevertheless, when digging into the details of the mining rankings provided by the Fraser Institute, questions abound. Table 1 displays, for the period 2015–2022, the results for nine jurisdictions across the world, which all at some point in time have been ranked among the top ten mining regions in terms of their IAI. It also reports the two composite rankings based on the BPMPI and the PPI, respectively.

Table 1 provides evidence of how the IAI rankings tend to bounce back and forth in a relatively erratic manner, and it highlights a few examples from both developed and developing countries of such rapid changes for each of the selected jurisdictions. For instance:

-

In 2019, Botswana ranked at 45 out of 77 mining jurisdictions. The year after its ranking was as high as 11, thereafter bouncing back to the position of 66, and then, in 2022, the country managed to climb up 56 spots and reach the top ten list.

-

Chile’s ranking of 39 in 2016 improved to 7 and 9 in 2017 and 2018, respectively. The coming year, however, it dropped to rank 17, and then to 30 in 2020.

-

Finland was ranked first in 2017. In 2018, the country dropped to rank 17, but bounced back to rank 2 in 2019. Over the period 2020–2022 Finland’s ranking dropped each year and turned out as low as 29 (out of 64) in 2022.

-

Manitoba (Canada) has also experienced some notable ups and downs, not least during the period 2015–2017 during which the jurisdiction was first ranked 19 (in 2015), then 2 in 2016, and back to 17 in 2017.

Similar erratic rankings can be observed for virtually all the jurisdictions listed in Table 1, as well as for additional regions not scrutinized here. Since the IAI ranking is based on a weighted average of the BPMPI and the PPI, this volatility can be traced back to changes in these two indexes. We now proceed by commenting on these indices separately.

An interesting and—one must contend—unexpected finding is that for the countries in Table 1 changes in the BPMPI appear to have overall contributed more to the rapid ups and downs in the IAI ranking than have changes in the PPI. For instance, for Botswana, the BPMPI ranking displays even higher volatility than the IAI ranking, e.g., jumping up 43 spots between 2019 and 2020, and then back 60 (!) spots down the year after that. Similar patterns can be found in Idaho, Manitoba, Portugal, Sweden, and Turkey.Footnote 7 In the cases of Chile and Finland, it is worth noting how the PPI rankings have remained relatively stable over time (see however below on political stability), while also in these cases the rankings based on the BPMPI have jumped up and down over the period. These findings do not only apply to the selected countries in Table 1: other examples can easily be detected when consulting the annual mining survey reports of the Fraser Institute (see also Keen 2015).

The reason why these rather erratic bounces are unexpected is that the BPMPI is supposed to represent a jurisdiction’s “pure” mineral potential, since respondents are asked to assume the presence of a “best practices” policy regime (Yunis and Aliakbari 2022). However, this geological potential is essentially the result of past natural developments occurring millions of years ago. Clearly, new discoveries can alter the perceptions of this potential quite quickly, such as in the case of the discoveries of the Voisey Bay nickel deposit and the Lac de Gras deposits in Canada can illustrate (Jara et al. 2008). However, such new information can hardly explain the sudden ups and downs in the BPMPI ranking. Thus, tectonic shifts in the perceived mineral potential do defy the geological timescales involved with mineral enrichment (see also Lasley 2023).

There are likely several reasons behind the erratic results for the BPMPI. First, the low response rate can certainly play a role. A low response rate implies that the perceptions of a small number of respondents can weigh in heavily on the aggregate score, and the specific individuals that respond could diverge from one year to the other. These individuals could in turn represent various types of companies, and with an interest in different minerals. Moreover, a low response rate increases the likelihood of gaming behavior, i.e., providing answers that serve the economic interest of the respondent but that do not necessarily reflect his/her true perceptions. In the next sub-section, we briefly comment on the potential occurrence of gaming behavior, e.g., on the part of exploration companies.

Second, the uneven BPMPI ranking can potentially also be attributed to a lack of validity. Keen (2015) comments on this ranking and notes that there is a clear risk that “respondents could not help but hold onto their bias against a place, due to knowledge or perception of impediments to exploration, which is precisely what the survey asked them to leave behind” (see Lasley (2023) as well as Casey (2022) for similar lines of reasoning).Footnote 8 It is of course difficult to provide direct evidence in support of this notion.

Nevertheless, there is a risk that the way in which the response alternatives are expressed could trigger biased responses, such as when choosing between the two positive response alternatives “encourages investment” and “is not a deterrent to investment.” Choosing between these two alternatives is far from straightforward; they tend to overlap, and, even more importantly, in the BPMPI case, the reference to “encourages” signals that there is an actor (e.g., a public authority) with the agency to influence the geological potential. However, as noted above, the whole point of the BPMPI is to assess what jurisdictions hold the highest potential for mineral discovery assuming there are no impediments to exploration, i.e., regardless of what the government does to encourage (or impede) such investments.

The ambition of the PPI is to provide a score card on how attractive the policies in the various regions are from the point of view of an exploration manager (Yunis and Aliakbari 2022). Still, also in this case, there could be reason to question the validity of the results, at least in the sense that these are hard to interpret and therefore difficult to use as the starting points for policy reform. One problem relates to the distinction between perceptions, which may not be based on facts but on reputations, on the one hand and reality on the other.

The overall low response rate and the fact that we have little information about the experiences and knowledge of the respondents make it difficult to assess the validity of the PPI and its various components. Several commentators—often with quite detailed knowledge about a few specific jurisdictions—have criticized the relevance of the PPI results from the Fraser Institute’s mining survey. A few examples from the recent years can be found in Ngatjheue (2020), Casey (2022), NewZWire (2023), and Mining for Zambia (2023) (see also above). In these articles, commentators often refer to the fact that recent trends in exploration expenditures for specific countries tell another story than the Fraser ranking. This is supported by Jara et al. (2008), who also point out that from an investment climate perspective, it is necessary to distinguish between various specific metals instead of (implicitly) assuming that the investment climate is equal across all metals (see also below).

The presence of a perception-reality gap can be traced to a lack of reliable information or pure ignorance. However, it can also be linked to a lack of validity in the sense that the perceptions underlying specific survey responses may not fully concern the issues that the questions intend to measure. The construction of the PPI is associated with challenges of measuring different concepts that are quite complex: taxation and political stability represent two specific examples. In both cases, there are concerns about concept validity.

First, in studies of mining policies, taxation tends to attract most attention, in part since it relates to hard economic facts with an obvious bottom-line impact but also since its quantitative nature (e.g., measures of the tax level) facilitates comparisons across jurisdictions. Gemell et al. (2016) compare the average effective tax rateFootnote 9 for a typical gold mining investment in 10 different jurisdictions—five in South America another five in Africa. The authors contrast these findings with the perceptions of mining taxation in the respective countries as reported in the 2014 Fraser Institute mining survey (see Jackson 2015) according to which the taxation regime includes “personal, corporate, payroll, capital, and other taxes and any complexity associated with tax compliance” (Yunis and Aliakbari 2022, p. 6).

The conclusion is that the perceived attractiveness of a jurisdiction’s fiscal regime, based on the ranking provided by the Fraser Institute, does not appear to correlate with the overall fiscal burden of some countries. Notable examples are Brazil and South Africa, which both have low overall tax rates for gold mining but are nonetheless judged as having some of the worst tax regimes. Hence, either the perceptions of mining executives do not match the taxation reality of operating in these countries, or there are other aspects of the tax policies that cause problems, such as an inefficient bureaucracy (Gemell et al. 2016). Still, even if it is the latter, the survey results do not teach us much about what the mining executives have based their responses on.

Second, in the case of “political stability,” the Fraser Institute provides no definition; it is up to the respondents to decide what this implies in practice. This can be contrasted with the World Bank’s so-called governance indicators out of which political stability is one. The World Bank states that political stability captures perceptions of the likelihood that the government will be destabilized or overthrown by unconstitutional or violent means, including politically motivated violence and terrorism (Kaufmann et al. 2010).Footnote 10 In 2020, the World Bank reported a ranking of political stability for a large number of countries, and 33 out of these also appeared in the 2020 mining survey from the Fraser Institute (Yunis and Aliakbari 2021).

This comparison shows that in some cases—e.g., Sweden, Spain, Ghana, Chile, and Papua New Guinea—there is a good match between the two rankings, but for many other countries, the results diverge a lot. For instance, Russia and Mozambique are both top ten countries (among the 33) in the Fraser ranking, while they are in the bottom third in the World Bank ranking. The positions of, for instance, Greenland, Ecuador, and Guyana are in contrast considerably more favorable in the World Bank ranking compared to the ranking of the Fraser Institute. As in the taxation case, this does not suggest that the Fraser Institute’s ranking (or the World Bank’s for that sake) is biased or false. There is however a problem of concept validity. Political stability is a concept that the science community has routinely described as “essentially contested” (e.g., Broome and Quirk 2015); the Fraser Institute does not even attempt to define it, and the survey results are therefore difficult to interpret and employ as the basis for future policy reforms.

Figure 2 provides another reason to question the validity of the political stability scores of the Fraser Institute. In this figure, we display the responses for four developed regions, which all have (at least occasionally) been ranked top ten in terms of the PPI: Sweden, Finland, Western Australia, and Saskatchewan. Just as in the case of the BPMPI, the data reveal significant ups and downs over time. For instance, the 2016 scores for Sweden display that almost 80 percent of the respondents answered that the political stability of the country “encouraged” exploration investment while only 20 percent responded that it was “not a deterrent” to such investments. After only three years, both response alternatives received an equal share of the total responses (around 50 percent). It is difficult to see what changes in the real world have led to this lower score. In the case of Finland, we find a similar—and an even more profound—response pattern. In 2021, the data for Finland show that almost 20 percent of the respondents perceived that the political stability of the country was a deterrent to exploration investment; in fact, 9 percent expressed that it was a “strong deterrent.” Similar erratic changes over time can also be found in the cases of Western Australia and Saskatchewan (see Fig. 2).

Political stability responses (frequencies) in four developed regions, 2011–2022. Note: In the survey, the respondents are confronted with five alternatives, and in the figures (a–d), “deterrent” is an aggregate of the three response alternatives “mild deterrent to exploration investment,” “strong deterrent to exploration investment,” and “would not pursue exploration investment in this region due to this factor.” Sources: the Fraser Institute annual survey of mining companies (various issues)

Just as in the case of the BPMPI, the volatility in the political stability scores can be traced to a low response rate, but also to a lack of concept validity. We simply do not know how the Fraser Institute defines political stability and what the respondents have in mind when they answer the survey. For this reason, it also becomes difficult to use the survey as the basis for future policy reforms. Finally, one can question how respondents are supposed to distinguish between a situation in which the political stability of a region “encourages investment” and one in which it (“only”) “is not a deterrent to investment.”Footnote 11

Finally, many of the policy factors addressed in the Fraser Institute’s mining survey tend to be closely related and thus overlap—e.g., uncertainty concerning environmental regulations, legal system, uncertainty concerning disputed land claims, uncertainty concerning what areas will be protected, and political stability. At the same time, however, there are policy factors that are ignored entirely. One example is the nature and the quality of what could be referred to as the mining innovation system, i.e., with indicators relating to the presence of research institutes, academic excellence, and government R&D support. Moreover, competence maintenance, i.e., relating to indicators such as access to skilled labor and the presence of mining schools, is key for modern mining activities. Presumably, it is the deregulation and free-market-oriented agenda that make the Fraser Institute to instead focus on the role of labor regulations and militancy.

The political rankings game

The Fraser Institute’s mining survey intends to provide a scorecard upon which various mining jurisdictions can be compared to each other, but the Institute is hardly a disinterested arbiter of information about the performance of governments worldwide. Commentators have pointed out the conservative and free-market-oriented agenda of the Institute (Kelpin and Johnson 2021; Osenton 2017), e.g., noting that the mining survey has been “nothing more than a content-free exercise in leveraging industry pressure for deregulation” (Keen 2015).

Regardless of outcome, the survey could provide fuel for highlighting any inadequacies of the existing mining policies. Still, there is a risk that it does not encourage a debate about difficult trade-offs. For instance, while low mining taxes will help improve the economic prospects of mining investment, they also reduce the opportunities to introduce tax-funded benefit-sharing mechanisms that in turn could improve the mining industry’s relations to the local community (Söderholm and Svahn 2015). The difficulty with mining investments does not only arise from difficult entry conditions, but also from the likelihood that the policies and the institutional conditions would be challenged by different stakeholders once an investment is successfully online (e.g., Fischer 2007; Humphreys 2000). This suggests that it is imperative to encourage a debate on the trade-offs involved in taxing and regulating mining on the one hand and aiding a more inclusive development on the other. The Fraser Institute, with its free-market-oriented agenda, therefore risks burying several vital political issues, such as domestic taxation regimes but also other issues such as indigenous rights, in a series of measures, scores, and assumptions that escape public scrutiny and dispute.

Still, despite the above, various actor groups do find it worthwhile to use the Fraser Institute’s mining survey to call for policy reforms. Governments could be influenced by the perceptions of domestic constituents, e.g., business organizations, opposition parties, non-governmental organizations, and international investors. In other words, the mining survey exerts pressure on the governments to compete in line with the values the IAI embodies. We could also note how the survey approach used by the Fraser Institute has inspired new research. One such example is Kulczycka et al. (2017), which in their assessment of the investment climate in the Polish mining industry however also does consider additional policy factors such as cooperations with research institutes as well as the qualifications and skills of the labor force.

As noted above, it is easy to find examples where mining companies and industry organizations have used the launch of the Fraser Institute’s mining survey as an opportunity to point out what they consider to be weaknesses in existing policies. For instance, the Minerals Council of South Africa (2022) reported on the poor performance of South Africa in the 2021 mining survey and remarked that this result ought to serve as an “alarming wakeup call” for the country’s mineral policy, such as dealing with a substantial backlog of mining and exploration rights applications (Minerals Council South Africa 2022). Lasley (2023) reports on how the launch of the 2022 survey has been used by the mining industry to point out how the US Environmental Protection Agency has put in place discharge bans that will make it very difficult to develop a mine at the interesting Pebble copper deposit in Alaska.

While low rankings provide fuel for criticizing a country’s mineral policies, high rankings can instead be met with skepticism by the domestic mining industry cluster. One example was when the Chamber of Mines of Namibia questioned the relatively high PPI score for Namibia in the 2019 survey of the Fraser Institute,Footnote 12 this by pointing out the low response rate for the country (between 5 and 9 responses) (Ngatjheue 2020). It is also possible to find examples of government’s seizing the opportunity to praise already decided changes in policy, such as when the Mines Minister of Ontario commented on the launch of the 2022 survey and argued that the recently launched Building More Mines Act would help to further improve the mining reputation of this Canadian province (Dufour 2023).

Thus, far from undergoing scrutiny, the Fraser Institute’s mining ranking enjoys fairly uncritical reporting in business media, which appears to be happy to report upon the annual fluctuations in the ranking as an international popularity contest. Instead, media legitimizes the ranking and helps keep the relevant actors attentive; these could even have a vested interest in overlooking the methodological flaws and negative side effects of the survey. Furthermore, regardless of outcome (i.e., low or high scores, negative or positive trends over time), the launch of the survey provides an opportunity to support the own interest. The above implies therefore that the Fraser Institute sets in motion a political rankings game in which governments, mining companies and executives, and other organized groups find it useful to join.

Figure 3 provides another illustration of this. It displays how many articles in Swedish media, e.g., editorials and opinion pieces, refer to the Fraser Institute’s annual mining survey over the period 2013–2021.Footnote 13 Each article is categorized as either pro-mining or anti-mining, i.e., based on whether they employ the published rankings as an opportunity to express support for the mining industry (and, for instance, call for more rapid licensing processes), or rather oppose exploration and mining activities (e.g., by arguing for stricter land-use regulations).

The thing that stands out the most in Fig. 3 is the correlation between Sweden’s ranking in the annual mining surveys on the one hand and the orientations of the articles published on the other. During the first half of the time period—a period during which Sweden received overall high rankings in the annual mining survey (not least based on the PPI)—all the editorials and opinion pieces argue against further mining expansion in the country. One argument was that Sweden’s high ranking revealed that the environmental regulations of mining operations were too lax. During the second half of the period, though, we witness the advent of less favorable rankings for Swedish mining policy (and geology), but at the same time, opinion pieces and editorials are now rather arguing for the introduction of more mining friendly policies, not least through a reform of the permitting processes, which are claimed to be both too slow and unpredictable (see also Svemin 2021). Thus, this confirms the notion that, regardless of outcome, the launch of the Fraser Institute’s mining survey provides an opportunity for at least some involved actors to express their views and argue for change.

However, regardless of whether the articles express support for the mining industry or not, none of them questions the reliability or validity of the survey. In fact, there are even signs of false interpretations. One example is the above-mentioned concern about the (lack of) stringency of the environmental regulations in Sweden (Wirtén and Arnbom 2014). The Fraser Institute’s survey does not ask about the opinions concerning the stringency of the regions’ environmental regulations; instead, it addresses the uncertainty concerning the environmental regulations, e.g., the stability of the regulations and the consistency and timeliness of regulatory processes.Footnote 14

As noted above, the Fraser Institute’s annual mining survey helps establish a political rankings game in which different types of actors (i.e., the “audience”) are keen to participate and promote their vested interests. The Institute provides the rules of the game and assumes the role of a referee. Nevertheless, this also means that the different actors may pursue the opportunity to influence the referee and change either the outcome of the survey or the rules, so-called gaming. The extent to which such gaming occurs is difficult to determine, but we end this assessment with a few anecdotal remarks on this issue.

One possibility is that governments may have an interest in influencing the survey, e.g., which questions are asked and how they are formulated. There is scarce evidence of such behavior. One of the interviewees, though, remarked that the Fraser Institute has received feedback from at least one national geological survey on the methodological approach to assess the quality of the jurisdictions’ geological databases. Such advice from government agencies can at best help improve the quality of the annual survey, but in the worst case there is a risk that the feedback is motivated by a desire to tilt the outcome of the survey in a way that favors the competitive position of the own country.

Exploration companies that are active in one country are often keen to provide a positive picture of the investment climate in that country. For instance, even if Zimbabwe was ranked last (at spot 62) in the 2022 mining survey, companies that are active in the country have expressed the opposite view, instead praising the country’s “assets” (NewZWire 2023). Fulp (2018) argues that junior companies tend to promote jurisdictions in which their flagship projects are located, and the CEOs of these will therefore have an interest in boosting that jurisdiction’s ranking. This remark is repeated in our interviews. One respondent argued that the survey of the Fraser Institute primarily attracts “CEOs who have a vested and biased interest in the country in which their projects occur, and thus use the results as a promotional tool,” while one of the Swedish respondents stated:

Views about Sweden – in general and not necessarily communicated to Fraser – are often more positive when an exploration campaign is under way. Still, when this campaign has come to an end – without any spectacular results – the perception of Sweden tends to be less positive.

While the above merely represents anecdotal evidence, it would still be naive to conclude that gaming does not in any way distort the results presented each year by the Fraser Institute. For many countries, the number of responses is—as noted above—very low, and this increases the likelihood that individual gaming behavior will be considered worthwhile. In other words, the low response rate increases the expected payoff of striving to manipulate the results in ways that is in accordance with one’s economic interests. And, if a low response rate is expected, it is reasonable to assume that companies that have such an interest in gaming will be overrepresented in the final sample (compared to the total population of companies).

Discussion

Our scrutiny of the annual mining survey of the Fraser Institute has departed from the research in the international relations literature on country performance indicators and global rankings. This scholarship includes a large body research criticizing the methodological veracity of the various rankings (e.g., Firchow and Ginty 2017; Jerven 2013). Our findings add to this critique in the empirical context of the Fraser Institute’s mining survey and display that there are strong reasons to question both the reliability and the validity of this survey.

First, the response rate is indeed low and has declined over time, thus raising serious concerns that the results will not reflect the true views of global mining executives but instead be biased towards reflecting the perceptions of, for instance, a certain type of mining company and/or executives with limited knowledge about the countries. There can even exist incentives among exploration companies to “game” the rankings. It is worth noting that during the studied period, the global non-ferrous mining industry alone has comprised over 3000 companies (according to the S&P Global Market Intelligence and reported in Fulp (2018)). However, since 2018 the total number of responses has consistently been below 300, and in 2022, it was only 180. From a statistical point of view, this is way too low, and no meaningful rankings will be generated.

Second, there are also concerns about concept validity that is by attempting to operationalize inherently complex concepts; there is a clear risk that the results measure something different than they are intended to measure. One prominent example is political stability, which is not defined by the Fraser Institute, and could involve very different things to people in the mining industry. This lack of concept validity—in combination with a very low response rate—likely explains the rapid ups and downs from one year to another in this policy factor. Such erratic bounces have been prevalent also in the results for geological potential, something that makes one question whether the respondents in this case are really capable of ignoring the policy issues and impediments that the survey asks them to leave behind. Even in the case of mining taxation, an area in which it is possible to (at least in part) rely on objective quantitative measures, there exist notable differences between the perceptions of these taxation regimes as reported in the Fraser survey on the one hand, and the actual fiscal burden on the other.

For the above reasons, the mining ranking presented by the Fraser Institute does not constitute a meaningful scorecard that countries can employ to improve their mining-related policies. It risks measuring skewed perceptions as well as building on questions—and response alternatives—that could be misinterpreted. It could be argued that even if the perceptions of the mining executives do not accurately reflect the actual policy environment or the geological potential in a certain region, they are relevant measures since these perceptions could have real-life impacts on the decisions of potential investors. Thus, it can be argued, even skewed perceptions, i.e., those based on past reputations rather than on objective facts, can be interesting to elicit. Still, such results cannot constitute the basis for significant policy reforms, e.g., the introduction of lower taxes and/or simplified regulations. Neither are they helpful for the mining industry nor the investment sector when evaluating potential investment decisions. At best, survey results based on skewed perceptions could encourage the launch of information campaigns that help improve the reputation of the jurisdiction (see also Casey (2022) on the biased reputations about mining attractiveness in several African countries).Footnote 15

The above does not suggest that surveys of the kind that the annual mining survey of the Fraser Institute represents are biased per default; often the elicitation of expert opinions can be useful for measuring soft factors that are difficult to estimate using quantitative information but that are nevertheless important for investors. Still, in the specific case of the Fraser Institute’s annual mining survey, there is room for methodological improvements. Specifically, there is an urgent need to improve the response rate, potentially by focusing on a smaller number of policy factors (see also below). As noted above, work could be done to better target the companies (including the state-owned enterprises) that are active in the various jurisdictions and potentially also the financial investors that have an interest in the mining industry.

Some of the concepts used, not the least political stability, need to be defined more clearly. One should also consider revising the way in which the response alternatives are presented, referring to the fact that the Fraser survey relies on so-called ordinal response categories. These types of scales should be clearly distinguished from each other so respondents can easily place their responses along the suggested continuum. However, as noted above, it can be questioned whether this criterion is met in the case of the mining survey.

Nevertheless, despite these deficiencies, the Fraser Institute’s mining survey often enjoys rather uncritical media attention. As noted by Beaumont and Towns (2021), these types of surveys even set in motion a political “rankings game” in which a wide range of various types of actors participate. By offering comparative information using simple rankings, the Fraser Institute can alter shared information, affect third party beliefs and opinions, and convince mining countries that their reputation is at stake. In this way, the Institute exerts competitive pressure on states to deregulate and reform. This type of policy influence has been analyzed also in the empirical context of the World Bank’s so-called EDB ranking. Doshi et al. (2019) show how, in this case, the ranking influences investor perceptions and how it also has shaped domestic policy in India. In this article, we have not investigated the relationship between the results of the Institute’s ranking on the one hand and actual policy reforms on the other—we simply note that the survey is used by various actors to lobby for such reforms—but this could be an area for future studies.

Still, neither in the EDB ranking nor the Fraser Institute’s mining ranking are there attempts to acknowledge the complexity of the regulatory reality and highlight the often-difficult trade-offs involved (e.g., in raising taxes for supporting a broader economic development). In both cases, external validation, or criticism, from a third-party organization, can for many actors be part of a strategy to strengthen a broad domestic coalition for policy reform. And as long as the ranking assists in this endeavor, there will be few incentives to question the reliability and validity of the results as well as the methodological approach used to generate the results.

Again, our findings should not be interpreted as suggesting that the survey-based approach to assessing investment attractiveness is flawed; the simple point is that the survey from the Fraser Institute does not live up to the promises made. However, it is useful to also comment—if only briefly—on alternative means of assessing the investment attractiveness in the global mining industry. As noted above, the exploration expenditures is the most commonly used indicator of mining competitiveness and investment attractiveness in the literature (Vásquez and Prialé Zevallos 2021). Jara et al. (2008) conclude that exploration expenditures can indeed be a useful indicator for these purposes. Other potential approaches have important drawbacks. As noted above, surveys risk measuring perceptions—and, at worst, reputations—rather than the actual behavior of mining companies and other more objective indicators, such as a country’s share of world production, suffer from the fact that due to large sunk costs; they primarily reflect changes in a country’s investment attractiveness after a significant lapse of time.

However, Jara et al. (2008) argue that a focus on exploration expenditures needs to be narrowed down to grassroots exploration; this because a change in the investment climate will have a rather direct impact on such exploration. This is in contrast to so-called late-stage exploration, which takes place when a mineral deposit has already been discovered, as well as mine site exploration, which corresponds to exploration at and immediately around mineral deposits or mines approved for production or already in operation. Such activities would often continue even in the presence of a significant decline in the investment climate.

Moreover, exploration expenditures could be a useful early indicator of a country’s investment attractiveness if it is limited to grassroots exploration for specific mineral minerals. This refers to the fact that due to market developments, exploration companies can, for instance, shift their targets away from the important mineral commodities that a certain country hosts. This “alters its share of world exploration expenditures for reasons completely independent of its mineral investment climate” (Jara et al. 2008, p. 186). Clearly, addressing specific metals rather than total exploration could be vital also in the survey-based approach. For instance, Casey (2022) notes that during recent years, Zimbabwe has been ranked very low in terms of the IAI in the Fraser Institute’s assessment (62 out of 62 in 2021, and 84 out of 84 in 2022), but the country is nevertheless the host of significant reserves of platinum group metals and chromium ore. If, as suggested by some (e.g., Vale and Herrmann 2004), gold exploration companies are over represented in the Institute’s survey, these rich mineral assets may have been neglected.

The above illustrates that also using exploration expenditures as an early indicator of investment attractiveness comes with many challenges, and it is fair to conclude that this approach is merely a complement rather than a substitute to survey-based approaches. In this context, it is useful to also mention the indicators that focus on specific determinants of investment attractiveness, such as the components aggregated into the PPI by the Fraser Institute. Even if these factors are incomplete indicators of the overall investment climate, they can provide important information about key aspects of this climate (see, for instance, Otto et al. (2006) for a detailed comparison of mining taxation across countries).

Specific policy factors could be more important for a certain category of investors, and also in this case, it is useful to view objective—directly measurable—indicators (e.g., tax burden) and the perceptions elicited in surveys as complements rather than substitutes. Some soft factors, e.g., perceptions of risk, could be more appropriate to assess based on a survey-based approach (given that the underlying concept is well-defined and understood), while other factors can be based on direct measures. The latter may include information about, for instance, the duration of the permitting processes, number of mining students, and government R&D expenditures.Footnote 16

Conclusions and avenues for future research

The purpose of this paper was to scrutinize the Fraser Institute’s assessment of the investment attractiveness of mining jurisdictions worldwide. The resulting ranking builds on eliciting the perceptions of industry representatives around the world through an annual survey, and in the mining industry, it is the most widely quoted country performance indicator. The paper shows that due to a low response rate and a lack of clear definitions of some of the underlying concepts (e.g., political stability), there are strong reasons to question both the reliability and the validity of the Fraser Institute’s results. These problems contribute to the rapid ups and downs from one year to another in terms of the ranking of several of the jurisdictions’ geological potential and policy factors. There is also likely to exist incentives among exploration companies to “game” the rankings.

For these reasons, the ranking outcomes do not, as frequently claimed by the Institute, constitute a meaningful scorecard that countries can employ to improve their mining-related policies. Neither do the results from the survey help investors make better decisions. In spite of the above deficiencies, however, the Fraser Institute’s mining survey often enjoys a lot of fairly uncritical media attention. It even establishes a political “rankings game” in which mining companies, governments, as well as other organized groups find it useful to participate, but none of these actors appears to have an interest in seriously scrutinizing the quality of the survey. Instead, they use the Fraser Institute’s rankings strategically to gain support for their interests (regardless of whether these interests support increased mining activities or not).

Apart from stressing the need for significant improvements in the survey of the Fraser Institute, our scrutiny invites additional research on the quality and use of various country performance indicators, in general and particularly in the mining industry. This involves future work on ways to improve the quality of survey-based approaches in general aiming at assessing the investment attractiveness of mining regions and countries in the world. There should also be room for future comparative studies on other—complementing—measures available for the same purpose, e.g., by building on the work by Jara et al. (2008) on using grassroots exploration expenditures as one early indicator. Such work needs to recognize differences in the investment climate across various specific mineral commodities. Additional work on measuring individual determinants of investment attractiveness is also called for. Finally, research is needed on the extent to which mining companies and the investment sector are in fact influenced by various global rankings of investment attractiveness and, in turn, the extent to which national governments will—as a consequence—try to improve their rankings to attract further investment.

Data availability

The authors declare that all raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Notes

In 1999, the Behre Dolbear Group, an influential mineral industry advisory company, started to issue annual political risk assessments of mining countries (e.g., Behre Dolbear 2010, 2013, 2015). However, the group does no longer conduct these assessments. See Oyunchimeg (2016) for a reference to this assessment in the case of Mongolia.

Independent Evaluation Group (2008) notes that the World Bank’s EDB index seeks to assess “the burden of regulation […] as seen from the private firm’s point of view” and thus not from the perspective of the net social benefits of the regulations.

In our assessment of the PPI, we focus primarily on the items that are included in the index rather than how the index is constructed, i.e., how the items are aggregated. The latter is, though, not straightforward, in part since many of the policy factors in the PPI (e.g., political stability and uncertainty about regulations) tend to overlap and also could interact in rather complex ways.

Vale and Herrmann (2004) report that the response rate was low also prior to this period, e.g., around 16 percent in the 2003 mining survey.

Relying on few responses does result in uncertain estimates. For instance, assume that one country has 20 responses from a total population of 3000 companies, and ten of these (i.e., 50 percent) state that its mineral potential is either “encouraging” or is “not a deterrent” to mineral investments. Based on this, a 95 percent confidence interval shows that between 29 and 71 percent of all companies have this positive perception, i.e., a margin of error as high as 0.21. This also implies that we cannot conclude that a corresponding share of 75 percent (18 out of 24) for another country is statistically different (at the 5 percent significance level) from the 50 percent share in the first case.

Mining for Zambia (2023) reports that the organization has asked the authors of the 2022 survey to indicate how many responses on Zambia they received in the last three years, and to share (on an anonymized basis) these respondents’ “positions” and “company focus.” Still, according to the organization, no response was provided.

Since 2021, the Fraser Institute has provided an Excel document displaying the specific responses to each of the questions posed in the annual mining survey. These illustrate, for instance, that the change in Botswana’s BPMPI ranking from spot 76 in 2021 to spot 22 in 2022 can be traced to a significant change in the underlying survey responses. Specifically, in 2021, zero (0) percent of the respondents answered that the country’s geology encouraged exploration while 62 percent answered that it was not a deterrent to such investments (and 38 percent chose some of the more negative response alternatives). In 2022, though, the corresponding responses were 59 percent and 27 percent, respectively, (now with only 14 percent choosing any of the negative responses). In both these years, Botswana received at least ten responses in the survey. This demonstrates thus that the rapid changes in the BPMPI ranking cannot be attributed to marginal changes in the underlying scores.

One should note that the quality of each jurisdiction’s geological database, including the quality and scale of maps as well as ease of access to geological information, is one of the components in the PPI and should thus not be interpreted as influencing the BPMPI.

The average effective tax rate (AETR) equals the economic rents paid to the state as a share of the entire economic rents generated over the lifetime of the mining project. The rents received by the state include corporate income tax, royalties, and any other payments required under that state’s mineral taxation policies.

This definition of political stability is highly relevant from a mineral exploration perspective. Jara et al. (2008) remark that where “internal coups, civil strife, and wars […], are likely, mineral exploration may not occur even where the geological potential is exceptional” (p. 179).

A similar problem emerges at the lower end of the scale. For the respondents, it is not straightforward to fully comprehend the distinction between “strong deterrent to investment” on the one hand, and “would not pursue investment due to this factor” on the other. One alternative could be to confront the respondents with a clearcut statement (also defining the concept), e.g., “political stability [in the form of …] is a strong deterrent to exploration investment” and then ask each respondent to what extent he/she agrees with this statement (e.g., using a fivepoint Likert scale with the end points “entirely agree” and “entirely disagree”).

In 2019, Nambia’s PPI resulted in a mineral policy ranking of 14 out of 76 jurisdictions, and in 2020, it bounced back to place 47 (out of 77) (Mejía and Aliakbari 2023).

The data have been drawn from the so-called Retriever database, which is the largest media archive in the Nordic countries that collects news from print and digital editorial media (www.retrievergroup.com). It should be noted that we have only counted original articles, i.e., many opinion pieces are published in several media outlets but these have only been counted once.

The Fraser Institute’s focus on the uncertainty—rather than the stringency—of environmental regulations makes sense. Research suggests that rather than being intimidated by strict environmental regulations, mining companies may be searching for it, or at least for the factors that the existence of such regulations represent, such as stable political and legal institutions (e.g., Tole and Koop 2011; Annandale and Taplin 2003; Söderholm et al. 2015). Furthermore, in the mining industry, differences in environmental compliance costs across countries may often be relatively unimportant since the multi-national companies tend to adopt the same technological and environmental standards independent of where they choose to operate (Peck et al. 1992; Rémy 2003). The most modern and cost-effective mining and exploration technologies are often the most environmentally friendly ones, and international mining companies are also exposed to scrutiny and pressure from the public, their shareholders, and the financial sector to pursue appropriate environmental conduct regardless of location.

The influence of reputations on the survey does result could also imply that jurisdictions which have had little past experiences of mining activities (and therefore no history of policy failures), will be ranked unjustifiably high.

It can be noted that also such “objective” indicators could be subject to gaming behavior, in such cases on the part of governments. For instance, by defining some concepts, e.g., government support to mining R&D, very generously, a government could give the impression that its policy is more investor friendly than it really is.

References

Annandale D, Taplin R (2003) Is environmental impact assessment regulation a ‘burden’ to private firms? Environ Impact Assess Rev 23(3):383–397

Arnoldi, M. (2023). Minerals Council engages anew with government over concerns raised in latest Fraser Institute Survey Creamer Media’s Mining Weekly, 5 May.

Beaumont P, Towns AE (2021) The rankings game: a relational approach to country performance indicators. Int Stud Rev 23:1467–1494

Dolbear B (2010) 2010 ranking of countries for mining investment: where “not to invest”. Behre Dolbear Group Inc., Sydney, Australia

Dolbear B (2013) 2013 ranking of countries for mining investment: where “not to invest”. Behre Dolbear Group Inc., Sydney, Australia

Dolbear B (2015) 2015 where to invest in mining. Behre Dolbear Group Inc., Sydney, Australia

Broome A, Homolar A, Kranke M (2018) Bad science: international organizations and the indirect power of global benchmarking. Eur J Int Relat 24(3):514–539

Broome A, Quirk J (2015) Governing the world at a distance: the practice of global benchmarking. Rev Int Stud 41(5):819–841

Casey JP (2022) Reputation versus resources: inside the Fraser Institute’s mining report. Min Technol (7 July)

Chamber of Mines of Namibia (2023) Chamber of Mines position on Namibia’s performance in the 2022 Fraser Institute annual survey of mining companies, Windhoek

Cooley A (2015) The emerging politics of international rankings and ratings: a framework for analysis. In: Cooley A, Snyder J (eds) Ranking the world: grading states as a tool of global governance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 60–84

Doshi R, Kelley JG, Simmons BA (2019) The power of ranking: the ease of doing business indicator and global regulatory behavior. Int Organ 73(3):611–643

Dufour A (2023) Some mining investors favor other provinces over Ontario. CBC News 7 June

Firchow P, Ginty RM (2017) Measuring peace: comparability, commensurability, and complementarity using bottom-up indicators. Int Stud Rev 19(1):6–27

Fischer C (2007) International experience with benefit-sharing. Instruments for extractive resources, Resources for the Future, Washington, DC

Freistein K (2016) Effects of indicator use: a comparison of poverty measuring instruments at the World Bank. J Comp Policy Anal: Res Pract 18(4):366–381

Fulp MS (2018) Why the Fraser mining survey is fake news. Kitco Commentaries 16 April