Abstract

Mining employment in Australia can be cyclical and volatile. Since the gold rush in the 1850s, Australia has experienced two major mining booms. The first was in the 1970s and the second (i.e., the mineral boom) was in the mid-2000s and so it is important to have a discussion about trends in the Australian mining industry and about employment during mining cycles. This study employs Australian mining industry data to investigate sectoral labor mobility (moving from one industry to another) when the business cycles have changed. This research has used quarterly data from 1950q1 to 2018q4 for several industries such as mining, the building and construction industry, rental, hiring and real estate services, transport, postal and warehousing, agriculture, forestry and fishing, and manufacturing to conduct an empirical analysis. The findings of this study provide evidence that the sectoral shift of mining employment in Australia’s mineral and resource industry is highly correlated and dependent on the world economic circumstances. What happens in the world economies has an important bearing on how shocks are transmitted to the Australian mining industry and other sectors. The study also shows that displaced mining workers move around from one industry to another. In particular, the building and construction, agricultural, fishing and forestry, manufacturing, and real estate industries are found to be highly affected by the movement of labor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The mining sector offers important economic benefits for citizens and communities of the Australian resource-rich states and is most notable in the form of employment opportunities, improved wages, developed infrastructure and tax revenues (Ejdemo 2013). In the resources sector, mining employment is categorized into three types: exploration, construction, and operation. These three types are based on the development stages of the mineral production cycle and are identified as being the main areas of employment in the resource and energy industry. In a notable address entitled Mining Booms and the Australian Economy, Battellino (2010) argues that the distinguishing feature of a mining boom is the substantial increase in mining investment in which reinvigorated wage demands and/or mining of the high demand mineral resources from emerging economies go on to have important macroeconomic impacts. These macroeconomic consequences are mainly caused by global events e.g., changes in the relative prices of commodities and the emergence of powerful new trading partners such as China and other Asian economies. An economic impact resulting from the mining boom was to strengthen the Australian economy. The mining boom increased investment in mining, improved income from mining activities and accelerated the need for increased infrastructure to service mining sites. Also, the mining boom accelerated population growth, which has added to the economic momentum. Assessing the macroeconomic impacts of labor mobility is, therefore, an important exercise. This is because the resource investment boom can be associated with a substantial adjustment in the labor market because strong demand for labor and the high wage rates on offer in the resources sector lures workers from other industries.

A surge in Australian mining investment from the mid-2000s until 2012 significantly boosted resources in sector-related employment. Large numbers of mining workers were required to build new mining facilities, particularly in the remote regional areas of the state of Western Australia (WA). During the mining boom, employment in mining increased sharply (with a 13.6% annual growth) between May 2005 and May 2012. The resource industry, therefore, represented one of the fastest growing industries in Australia over this period (NAB Group Economics 2016). According to the NAB (National Australia Bank) Group Economics (2016), the employment trends during the three main mining development stages created at least 122,000 mining construction jobs between the beginning of the mining boom (2004–2005) and its peak (2012–2013), compared with 34,000 operational jobs and 13,000 exploration-related jobs.

Labor mobility is an important aspect of the success of the mineral and resource industry (Mineral Council of Australia 2013). It plays a role in reallocating workers between jobs and is crucial in helping the economic flexibility that facilitates adjustment to economic shocks and structural change. Movement within the labor market allows workers to be matched with a suitable job that fits their interests and be economically productive (D'Arcy et al. 2012). In the Australian mineral and resource sector, Long Distance Commuting (LDC) or Fly-in/Fly-out (FIFO) plays a critical role in the economy by providing an alternative to permanent relocation that enables mining workers to take advantage of stronger labor market conditions without incurring all the costs of LDC. The advantage of the LDC is to solve the labor issue by helping mining companies meet their labor requirements by using mining workers who are reluctant to move permanently to remote areas (Mineral Council of Australia 2013).

Given the extent of the downturn in mining investment in the current economic climate, mining employment in Australia has been relatively resilient. A study conducted by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has shown that mining investment and employment in the resource and energy sectors grew rapidly in 2013 but are expected to fall in the coming years due to the significant decline in commodity prices that began in 2014 (Kent 2016). In particular, resource construction activity in mining is expected to decline as a result of current mining projects reaching completion.

Towards the end of the mining boom and the larger-than-expected declines in iron ore prices, it was predicted that 46,000 mining jobs would be shed between the peaks in 2012–2013 and 2014–2015. Economists have also estimated that another 50,000 mining-related jobs will be cut in WA and Queensland (Qld) (NAB Group Economics 2016). In particular, mining workers in WA are the most likely to encounter job losses. This is because total mining investment and employment cycles in WA are currently less developed. Western Australia accounts for a large proportion of the total mining investment employment in Australia and the labor intensity of commodity projects is lower during the operational phase in WA. This downturn has obliged mining companies to review their business strategies and contemplate laying off workers and closing down their least profitable mining sites (Cordes et al. 2016).

The bust in the resource sector has caused significant turbulence in Australia and is expected to continue gradually over the next few years. However, the change in mining employment activities at the national level should still be manageable. More specifically, the remote regional areas and specialized skill groups will be disproportionately affected due to structural mismatches.

Australia has experienced two major mining booms. The first was in the 1970s and the second (i.e., the mineral boom) was in the mid-2000s. In particular, the resources boom over the first decade of the 2000s underscores the spatial and temporal complexities and contrasts of contemporary globalization. To meet the demand for mineral resources for the growing markets in India and China, mining companies have utilized spatially expansive and capital-intensive mining technologies to mine purely fixed mineral ore bodies and reserves in remote regional countries’ towns. This remarkable resource and mining boom has been leveraged by near-frictionless capital movements and because the mining sector is serviced by highly mobile non-local mining workers (Robertson and Argent 2016). These services such as accommodation, social interaction, entertainment and food had been well established by State Governments and mining companies in post period of the 1980s in order to meet the day-to-day mining workers daily essential needs while working on-site. This includes State Governments’ attempts to ‘pin down’ investment capital, and mining, resource and service sector labor in planned township sites to create long-term, and socially and economically sustainable mining communities in remote mining sites. These arrangements have been preferred by mining companies (Storey 2001; McKenzie et al. 2014).

In mineral and mining research, most of the literature has discussed the township adjacent to, or within close proximity, to mine sites (Robertson and Argent 2016). The mobility of labor is not necessarily seen in a positive light. Rampellini and Veenendaal (2016) suggest that the majority of research studies into labor force mobility in the mining and resource sector emphasize economic and social factors. Labor mobility, especially the subject of jobs and skills in the context of the resource industry, has been paid much attention. However, the question concerning how many and what types of jobs the resource industry can offer to local communities remains unresolved (Dietsche 2020). The Australian economy, during its different cycles, often experiences both labor and skill shortages (Atkinson and Hargreaves 2014). Therefore, this present study examines labor mobility and its structural changes that are linked to Australian business cycles in the resource sector. Importantly, this paper provides an in-depth analysis about Australian labor movement between sectors when the business cycles change and how retrenched mining workers use their skills to transfer from one sector to another.

This study uses the real business cycle models to investigate the cyclical change in the mining industry. Real business models express the idea that aggregate economic variables are the outcomes of the decisions made by mining companies or individual agents acting to maximize their utilities subject to production possibilities and resource constraints (Plosser 1989). The decisions made by mining firms following a change in macroeconomic fluctuations can affect mining companies’ productivity and their workers. As a small open economy with free capital flows, the linkages (e.g., the effect of changes in world demand on commodity prices) can affect the Australian economy (Downes et al. 1997). Downes et al. 1997 argue that changes in labor market activities played a critical role in the Australian business cycles, especially the labor movement in the 1980s and 1990s, and are included in this present research on how business cycles can influence labor mobility in the Australian mineral resource sector. The predictions based on research into the sectoral labor market in North America and Europe are very similar. For example, these sectoral labor market studies in North America and Europe indicate that the dispersion of the sectoral employment growth rate (σ) is positively correlated with the unemployment rate.

The Lilian index has been used to analyze sectoral labor mobility of mining workers moving from one sector to another. This index allows for measuring the sectoral shifts of employment activities among sectoral industries. In this study, the researchers employed quarterly data for six major Australian industries from 1950q1 to 2018q4 to investigate the relationship between sectoral industry workers’ turnover and the structural movement of employment from the mining industry to other sectors. To compute the index, the authors followed the method used in Ansari et al. (2013).Footnote 1 To compare with the previous literature that has applied the index, we use Australia’s aggregate data to examine the sectoral shift in labor mobility. By contrast, other mainstream literature has included a country’s geographical area or region to compute the index.

Since Australia has experienced two major mining booms since the gold rush in the 1850s, the Australian mining industry is now experiencing a highly volatile situation concerning its commodity exports. This is a critical issue currently faced by the Australian economy because how mining contributes to job opportunities has become increasingly important in mining states such as WA and Qld (Grudnoff 2012). More specifically, while a boom in one sector such as the resources industry of the economy can improve national income, not every sector or individual is certain to gain (Anderson 2018). The following questions are asked and answered in the empirical analysis: Is the Australian economy strongly dependent on the resource industry? If so, can labor shortages result from the mining cycles?

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The “Australia’s mining employment cycle: an overview” section presents an overview of the Australian mining employment cycle. The “The economic impact of Australia’s mining cycle” section demonstrates the economic impact of mining employment both before and after the resource boom in Australia. This is followed by the research methodology in the “Research methodology” section. The “Descriptions of data sources” section discusses the sources of data and is followed by the empirical analysis in the “Analysis of empirical results” section. Finally, the “Conclusions” section provides concluding remarks.

Australia’s mining employment cycle: an overview

The Australian labor market could be considered a unified whole between World War II and 1970. On average, in different business cycles, income per capita grows by approximately 2% per annum and, in one way or another, almost everyone shares in the growth (Gregory 2012). China-led growth has had a significant effect on the Australian economy. The resource boom in the 2000s has led Australia to bypass the most serious global economic downturn since the Great Depression of the 1930s. During the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the Australian government implemented the second-largest stimulus package in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to prevent a significant rise in the unemployment rate that was forecast to peak at 8.5% (Australian Treasury 2009).

Two years after the GFC, the Australian economy boomed again. During this period, there was no substantial downturn. This can mainly be attributed to the China effect, whereby rapid urbanization led to heavy demand for Australia’s mineral resources, such as iron ore. The unemployment rate increased in this period but only to a moderate level (i.e., 5.8%). According to the governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), this mining boom is the biggest resource boom since the gold rush of the 1850s because the recent resource expansion had a significant impact on Australia’s economic future.Footnote 2

There are many studies such as Haslam McKenzie (2010), Tonts (2010), Measham et al. (2013) and Haslam McKenzie (2020) to address issues concerning the current mineral boom in Australia and whether the new resource-led economy, associated with its large investment in infrastructure, will change the nature of the labor market in the resource sector. These studies are worth noting. Haslam McKenzie (2010) asserts that the resource boom in mining states such as WA has had far-reaching impacts on rural regions. The remote communities are overwhelmed by a new population connected with mining that creates a range of social and economic stresses and strains for these regional towns and communities. Tonts (2010) discusses the labor shortages in WA’s Goldfields mineral resource sector. The study by Tonts demonstrates the resource sector labor market is closely determined by mineral prices, labor supply and demand, and resource output. Importantly, the mining workers shift from firm to firm in search of higher wages and/or better conditions. Measham et al. (2013) argue that the current mining boom in Australia is remarkable for the changes it is driving in communities and one of the key features driving economic and social transition is employee mobility and the proliferation of long-distance commuting (LDC); in particular, Fly-in/fly-out (FIFO), which has accelerated throughout the recent mining boom. Haslam McKenzie (2020) explores the role of LDC as a tool for mitigating the impacts of the boom-and-bust cycles in the resource industries of WA. The research concludes that the labor demands during the mining boom were largely met by the private sector through FIFO arrangements. When the mining bust occurred, the host communities did not experience a sudden depopulation and withdrawal of services. In fact, the decreased demand for FIFO workers was moderated and the effect on WA’s Perth city was comparatively modest.

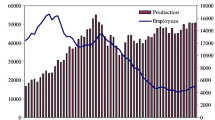

These studies indicate that a new and different labor market in the mineral sector is beginning to emerge; however, the new feature of the labor market in this sector leans more toward the phenomenon of a two-tailed economy in Australia (Gregory 2012). Figure 1 demonstrates the trend of total mining employment in Australia by comparing the decrease in demand with other sectors such as agriculture, forestry and fisheries, and the manufacturing industries. The reason we use these three sectors in the main comparison in Fig. 1 is because the Australian economy has been gradually moving away from agriculture and manufacturing toward the services industry, and the mining and resource sector is growing significantly (Connolly and Lewis 2010). Therefore, a comparison of these three industries is worthwhile to provide insights into which of the mining and resource sectors have provided a resurgence lifting the industry’s share of investment, output, and exports, and contributing a large proportion of economic revenues for the states of Qld and WA.

Source: Australia Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Catalogue number: 6291.0.55.002; ABS Catalogue number: 8412.0

Trend of mining employment in Australia. Manufacturing and Agriculture, and Forestry and Fisheries sectors are the most related sectoral industries with which to compare the trends and cycles in the mining industry

The figure shows that total employment in the resource sector increased significantly during the period of the mining boom. However, the employment trend in mining in 2012 shows a different picture as the mining boom was approaching its end. Even though the mining cycle was declining, the other two industries presented indicated no sign of recovery. Mining employment in Australia is more relative and is influenced by the international market rather than the domestic economy.Footnote 3

Australian sector economies had experienced significant structural changes from 2010 to 2016 (Hereth and Jayanthakumaran 2020). The rapid growth in the resource sector has provided a positive effect, especially on regional areas, by promoting labor demand, investments, intermediate inputs, taxes, royalties and other services. In Australia, several empirical studies have discussed changes in regional employment and regional specialization. Dixon and Freebairn (2009) found that the level of regional specialization in Australia had declined due to de-specialization in manufacturing resulting in substantial tariff reductions over the last 20 years. Hicks et al. (2014) investigated the Australian employment specialization from 2001 to 2006. Their study found that while there was little evidence of employment specialization in Australia, regions tended to have a higher level of employment specialization than metropolitan areas.

Australia is endowed with the world’s second-largest stock of economically demonstrated reserves of iron ore and has the fifth-largest stock of proven reserves of black coal (Robson 2015). These endowments, a relatively free market, and its institutions (in particular, the nation’s political stability, private property rights and the rule of law) have played a significant role in helping to ensure that the resource industries have achieved a high level of production capacity and will be able to maintain innovation.

The economic impact of Australia’s mining cycle

One common phenomenon in mining analysis that causes some aspects of structural change in an open economy is what is known as ‘Dutch disease’ and also referred to as de-industrialization. The term de-industrialization is usually applied to the movement of labor away from one sector (non-flourishing sector) to another (rising sector) (Tyers and Walker 2016). Therefore, the Australian economy has been forced to cope repeatedly with structural adjustments associated with the resource movement effects and de-industrialization that attracts large scale immigration and an increased female labor force participation in the booming sector.

Standard economic analysis of the mining boom reveals a two-speed economy in Australia, which the prominent Australian economist Corden (1984), and Corden and Neary (1982), researched in depth several decades ago.Footnote 4 Their research helped to shed light on the overall macroeconomic and distributional impact of the recent Australian mining boom episode.Footnote 5 The subject has now been further researched by Tyers and Walker (2016) who examine Australia’s terms-of-trade boom since 2003.

Over the years, the Australian economy has experienced shocks. These include the current mining export boom, notably a gold rush or two, and several agricultural trade booms in wool and other commodities (especially in the 1970s), as well as earlier mining booms in the 1970s and 1980s (Banks 2011). Each of these shocks prompted a new era of structural changes in the Australian economy that has ultimately brought about adjustment or a new equilibrium.

It is important to understand the nature of cyclical employment activities. This is because the cyclical fluctuation in the labor market can explain how the Australian economy responds to changes in economic conditions both locally and internationally (Evans et al. 2019). One common phenomenon in the Australian mining industry is labor mobility, which is one of the core elements of a well-functioning labor market. Atkinson and Hargreaves (2014) suggest that labor and skill shortages are the most common features in the various cycles of Australia’s economy. They argue that labor mobility is strongly related to mining cycles. During a cycle in a slow labor market, mining workers may choose to move to more stable employment, while in a buoyant-economy cycle, mining employers use incentives to influence the mobility of mineworkers. This mining boom led to a substantial increase in the demand for labor in the resource-rich states of WA and Qld for particular type of highly skilled workers, such as engineers, as well as less-skilled laborers, such as machinery operators and laborers (Bishop 2019).

Aggregate data is used to look for insight into the Australian total mining employment and its exploration expenditures. Figure 2 explains the trend of total mining investment associated with total mining employment activities in Australia. The figure suggests that the recruitment of mining staff is dependent heavily on the investment climates of the mining firms, which are affected by the world economic activities. The figure also indicates that the employability of mining staff had declined since 2013 because of the significant decline in the total mining investment activities in Australia.

Australia’s significant expansion of commodity exports suggest that broader dimensions of industries can be vulnerable because of the resource curse that results from dependence on extractive industries, notwithstanding other factors which may ameliorate or exacerbate this vulnerability (Goodman and Worth 2008). This is particularly the case for mining states such as WA given its high concentration of mineral endowments and high reliance on the resource industry. In many perspectives, mining in WA is according to “proof of potential benefits of resource dependency,” (Goodman and Worth 2008, p. 206) and the resource industry in WA and in mining states such as Northern Territory (NT) and Qld, is positively associated with income, housing affordability, communication access, educational attainment, and employment at regional Australia (Brueckner et al. 2014). In addressing this issue, a model of mobility in mining labor, particularly mining employment, is discussed in the following section.

Research methodology

In Australia, the mining industry accounts for 2.1% of the country’s total employment (Australian Government 2021). This employment is highly concentrated in the mining states, such as the NT, WA (excluding Perth), and Qld (excluding Brisbane) (Connolly and Orsmond 2011. However, mining is very capital-intensive and, hence, the size of the labor force utilized in mining operations has remained comparatively small.Footnote 6

There have been many business cycle model studies. These studies have focused on the business cycle in the resource industry in general, as well as on the employment associated with macroeconomic fluctuations (Barsky and Kilian 2004; Cho and Cooley 1994; Debelle and Vickery 1998; Fuentes and Garcia 2016; Merz 1995). However, there is a lack of studies that specifically address mining employment in Australian business cycles. Therefore, this present study discusses the employment activities in the Australian mineral sector that are largely affected by changes in economic activity in the resource industry.

There are two strands of research about Australia’s labor demand (Mowbray et al. 2009). The first is research based on partial equilibrium elasticities. This research considers the first-round effect of changes in real wages on employment and abstracts from second-round effects. For example, changes in real wages affect the gross domestic product (GDP), which then feeds back into employment. The second group is the general equilibrium elasticities. This model aims to incorporate the first-round and second-round effects of changes in real wages on employment. As a result of this effect (using the general equilibrium elasticities method), the real-wage elasticities sourced from general equilibrium models tend to be significantly larger compared with partial equilibrium estimates.

One groundbreaking study on the resource sector and business cycle is the study conducted by Fuentes and Garcia (2016). Their study examines the mining sector against the Chilean business cycle by constructing and estimating a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium model that explicitly includes the connections between the mining sector and other production sectors in the remainder of the economy. The empirical results show that the copper price is a dominant factor in explaining the upsurge of growth in the Chilean economy. It is important to realize that the output depends on inputs largely supplied by the remainder of Chile’s economy. Therefore, a change in copper price can play a critical role in positively affecting many other industries in Chile’s economy.

Doyle (2014) studied the labor movements in Australia during the resource boom and investigated how the resources sector was able to increase employment so rapidly by considering the characteristics of workers who, in general, moved into resource construction jobs. Doyle (2014) argues that the recent peak in the resources sector in 2013 and the earlier increase in resource construction employment largely drew on workers with experience in other types of construction. The study also finds that resource construction workers are generally expected to be able to find work in other industries, such as residential and civil construction sectors, since a large number of resource construction jobs are ending.

Concerning employment activity in mining in Australia, some previous studies have provided support for the idea that the dispersion of sector employment growth and the sectoral unemployment rate are positively correlated (Abraham and Katz 1986; Garonna and Sica 2000; Lilien 1982; Lucas and Prescott 1974; Taiwo 2013). The positive relationship between employment growth rates and unemployment indicates that sectoral shifts in aggregate labor demand are responsible for a substantial fraction of cyclical fluctuations in unemployment. The majority of these studies have followed the groundbreaking contribution of Lilien (1982) and the Lilien Index.Footnote 7

Since the development of the Lilien Index, several key points have emerged. First, aggregate demand fluctuations can develop through different industries based on the dispersion in employment growth rates and unemployment variability. Second, the employment growth rates can be anticipated and affected by aggregate demand pressure when they are due to structural shifts at the sectoral level. Therefore, there is a belief that the Lilien index can decompose or capture aggregate demand influences; even the purged structural shifts at the sectoral level. Finally, many empirical studies have confirmed the existence of a significant Lilian effect on unemployment (Loungani et al. 1990; Bachmann and Burda 2007; Basile et al. 2011). In other words, there is a positive relationship between unemployment and sectoral labor reallocations.

In the case of the United States of America (USA), Abraham and Katz (1986) found that labor employment in the manufacturing industry grows less rapidly but tends to respond more to the business cycle. In contrast, the service industry grows more but with minimum cyclical sensitivity. Indeed, many labor market studies have supported the idea that the Lilien index (σ) moves anti-cyclically in US labor employment activity (Abraham and Katz 1986; Neelin 1987).

The model used in this present study follows the research by Garonna and Sica (2000). We can begin by using the model with a two-sector economy, where Sector One represents the mining industry, and Sector Two represents the building and construction industry. We can assume that the pace of growth of the building and construction industry is more rapid than in the mining industry and is more responsive and sensitive to cyclical movement in the GDP.Footnote 8 The researcher can apply these assumptions using the following two-equation model:

and

where 1 and 2 represent the mining and building and construction industries, respectively. E1 and E2 are employment in the two sectors; Yt is the actual GDP and \({Y}_{t}^{*}\) is the trend GDP, which can be obtained through the Hodrick-Prescott filter. \({\Gamma }_{1}\) > \({\Gamma }_{2}\) represent the fact that the building and construction sector is growing at a more rapid rate than is the mining industry, and \({\upgamma }_{1}\) < \({\gamma }_{2}\) indicates that the building and construction industry is less cyclically responsive than the mining industry.

Following the study in Neelin (1987), we again developed a model for testing the relationship between the sectoral labor movement of the resource sector and other industries using quarterly data from 1950q1 to 2018q4. We test how the technology and labor changes have caused the evolution and mobility of resource sector workers from one industry to another when the mining employment cycle has changed. We estimate the model by regressing the employment growth rates on a constant; the current and one lagged value of both capital and labor shares and a time trend. The model can be written as the following:

where \({\dot{l}}_{it}=log{l}_{t}-{logl}_{t-1}\) is the mining employment growth rate of i where i indicates the six sectors mentioned above at time t. c represents a constant employment growth rate, \({Lshare}_{t}\) denotes the labor productivity index, \({Cshare}_{t}\) represents the capital productivity index. \({Lshare}_{t-1} and {Cshare}_{t-1}\) represent as the one lagged value of the unanticipated employment growth rate. The Trend indicates a time trend.

Using dispersion in the growth rate of employment across the sectors (based on the total employment) at any point in time, the Lilien index (σ) can be developed as follows:

Based on the coefficients \({\Gamma }_{1}\), \({\Gamma }_{2}\), \({\upgamma }_{1}\), \({\gamma }_{2}\), as well as the actual and trend rates of GDP growth, the estimation of σt can be written as:

The values of the coefficients are critical. The key idea of estimating the coefficients is to enable the researchers to determine the σt and to identify how this variable moves over the business cycle. If \({\upgamma }_{1}-{\gamma }_{2}<0\), then the building and construction sector is more responsive to cyclical movement in the GDP than is the mining sector. The second term in the approximate expression for \({\sigma }_{t}\) is positive when the actual rate of GDP growth falls short of the trend rate of GDP growth (during a downturn), and it is negative when the actual rate of GDP growth exceeds the trend rate of GDP growth (during an upturn). Furthermore, the value of \({\sigma }_{t}\) increases during downturns and decreases during upturns in the Australian business cycle.

Descriptions of data sources

This study employs Australian mining industry data to determine sectoral labor mobility activity during the resource boom and bust. It is imperative that the different phases of the business cycle, which the Australian economy has experienced since the 1950s, are identified. To test the model, the authors used quarterly data from 1950q1 to 2018q4. The sectors considered are the following: mining, the building and construction industry, rental, hiring and real estate services, transport, postal and warehousing, agriculture, forestry and fishing, and manufacturing.

For the employment dataset with respect to the above mentioned six industrial sectors, these data were collected from the Australia Bureau of Statistics (ABS) catalogue number 6291.0.55.002 and data available from 1974 to the present. The labor and capital share index data were obtained from the ABS catalogue number 8412.0 available from 1985 until the present. Because of the limited availability of this dataset, the researchers decided to apply the data from 1985 onwards. For GDP data, the dataset was obtained from the ABS catalogue number 5206.0 and data available from 1959 to the present. These datasets are the aggregate datasets and are the official ones as provided by the ABS. For the dataset prior to 1974, due to limited data availability, the researchers manually collected data from the ABS past released hardcopy documents.

Before conducting the empirical analysis using models (1) to (5), an estimation of the trend of GDP and the growth rates of sectoral employment in response to fluctuations in GDP is required and mandatory for the authors’ calculations. For example, the Hodrick-Prescott filter is used to estimate the trend of the GDP. Table 1 presents the description of the data sources.

The motivation for using this quarterly data stems from the fact that during the first half of the twentieth century, Australia experienced a turbulent period (Harding 2002). The Australian economy experienced eight major recessions compared with only three major recessions in the second half of the century. The researchers believe this historical background is noteworthy when examining mining employment in depth as the Australian economy has undergone significant reforms since these periods.

Following theoretical discussion and empirical evidence in terms of the business cycle in mining labor mobility in Australia’s economy, the researchers believe the data used in the study is straightforward. Data sources are available from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the Australian Government Department of Industry and, to a lesser extent, the Australian Productivity Commission and the Google search engine. The software used for the empirical analysis in this study is Stata SE (version 16.1).

Analysis of empirical results

Mining employment in Australia can be cyclical and volatile. We used Australia, China and the United States (USA) GDP data to explain the mining trend in Australia. These GDPs can be useful in explaining how the Australian mining cycle reacted to the world economy. This figure is particularly important to evidence the trend of the Australian economy related to sectoral industries; especially the mineral, resource and mining sectors. Figure 3 indicates that mining industry employment is determined by fluctuations in the business cycles of the Australian economy and the economies of the world. The figure shows the business cycles for Australia and the other two major economies in the world. The figure also indicates that Australia’s economy is highly correlated with the world economy, particularly since the GFC. The Australian economy is more heavily reliant on Chinese business activities than those of its traditional counterpart, the USA.

Figures 4 and 5 show the cyclical employment activities in Australia for the mining and construction industries. By applying the Hodrick-Prescott (HP) filter in models 1 and 2, Figs. 4 and 5 explain that the employment cycles in the Australian mining and building and construction sectors are significantly correlated. These two sectors are highly affected by domestic and international economic climates. It is evident that the resource sector has played a significant contribution to the WA, NT and Qld economies (Roarty 2010). The Australian minerals industry is also a major contributor to investment, high-wage jobs and exports and to government revenues in Australia. The industry has generated a total of 1.1 million direct and indirect jobs in the mining and related sectors (Zakharia 2020).

Australian mining employment activities are strongly connected to business cycles worldwide (Minerals Council of Australia 2021). In Fig. 4, we estimate the cycles of mining employment using the Hodrick-Prescott (HP) filter in association with the business cycles. The grey bars show the recession in each cycle using the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) cycles. Applying the NBER record cycles, Fig. 4 shows that the current trend supports the idea that the mining industry is very volatile and fluctuates based on the worldwide economic climate (e.g., the GFC in the USA and the trade war that is currently occurring between China and the USA).

Again, we construct the figure using a method similar to that mentioned above, which is the HP filter and NBER cycle in estimating business cycles and the activities in the building and construction sector as shown in Fig. 5. By contrast, Fig. 5 draws a different version of the story in the building and construction sector. This figure demonstrates that the cycles of this sector are more strongly connected to the domestic economy than to the worldwide economic climate. It appears that the volatility of mining cycles in Australia can also affect domestic industries. The employment impacts of mining are, however, far from straightforward to explain. The figure clearly shows that increases in the number of employees in the mining sector can cause changes in the number of employees in other industries. From the empirical perspective, the employability of the sector is caused by mining-related job multipliers (Moritz et al. 2017). Figure 5 illustrates that the mining industry in Australia plummeted significantly in the previous recessions (i.e., in the1970s and 2000s). However, it does not show much volatility in the building and construction industry. Indeed, the boom and bust of the mining industry only affected the mining states (e.g., Qld and WA). Other states, such as New South Wales and Victoria, are more focused on services, retail, and the property market.

The business cycles in Australia, as shown in Fig. 3, indicate that the resource industry is the major contributor to the Australian economy and provides significant inputs, such as advanced technological development, to Australian industries. The economic impact of the mining sector is important because the sector delivers economic wealth through exports, GDP, employment, government revenue and investment in infrastructure and in research and development (R&D) to Australians (Australian Government 2022). A substantial change in the mining and resource sector will affect employment activity as well as having an impact on other sectors such as the building and construction sector, financial and retail services, and transportation and storage services. Nevertheless, the business cycles (as shown in Figs. 4 and 5) are capable of reflecting employment activities in the mining industry. The figures show similarity to the research conducted by Doyle (2014), who finds that the resources sector can increase employment substantially by recruiting workers whose skills are readily transferable from other types of construction.

Since we have identified the connection between Australian business cycles and employment activity in the resource and building and construction industries, it is imperative to understand how the GDP growth is related to the employability of mining workers in the resource sectors. Sensitivity analysis using elasticities to test the model is helpful in explaining labor movement within the resource industry over different cycles. This empirical test is applied using the model to investigate labor mobility in the resource and mining industries.

The empirical test of the models (1) and (2) investigates the sectoral employment mobility in various industries related to GDP fluctuations in Australia. Table 2 demonstrates the cyclical employment of selected industries in the Australian economy. Our findings are relatively different compared to the study conducted by Garonna and Sica (2000). We found that the responsiveness of mining employment is negative (i.e., 1.315). By contrast, the responsiveness of other industries is positive. We agree that there is a major difference that characterizes the Italian and European markets compared to the Australian markets, and this accounts for an expected negative correlation between \({\sigma }_{t}\) and employment.

Table 2 also demonstrates a clear picture of Australian industries in which the mining sector plays a key role in the Australian economy by creating a job multiplier in other industries. This multiplier effect can also have an impact on the employment activities of other sectors. The table also demonstrates that the current downturn in the mining sector is connected with the significant volatility inherent in the worldwide economic climate and can significantly affect domestic industries. This is the case with the building and construction industry, agriculture, forestry and fishing, manufacturing, rental, hiring and real estate services, transport, and postal and warehousing services. Australia is similar to other nations, such as Italy, in that it also believes that employment protection legislation, the wage gap, sheltered product market conditions, subsidized lay-off programs, and other institutional arrangements are capable of minimizing the cyclical responsiveness of employment variations in the mining industry.

Table 3 presents the empirical evidence of the evolution and mobility of mining workers based on the estimation of labor and capital indexes.Footnote 9 The result illustrates statistical significance between the mobility of resource and mineral workers and the mining cycles. These mining workers do move around from one industry to another and, in particular, the labor movement is most affected in the building and construction, agricultural, fishing and forestry, manufacturing, and real estate industries. This is not surprising given that these industries are highly related to mining sectors. The empirical evidence shows that the mining sector is highly correlated with the transport industry. This is because the resource sector is a highly capital-intensive industry (Foo et al. 2018). Therefore, when the mining industry expands, demand for more transportation increases because more goods need to be moved to and from the mines.

Table 4 gives an overview of cyclical mining employment in Australia. It applies the two-factor model by comparing two major sectors in Australia: the mining sector and the building and construction industry. We found that employment in the Australian mining sector is cyclical and responsive to both domestic and international economic activity. Employment activity in the mining sector is significantly connected (as shown in the results presented in Table 2 [i.e., 0.20]) and dependent on economic growth. The cyclical changes and responsiveness of mining employment activity are also sensitive to what occurs in Australia and worldwide.Footnote 10 In other words, the study finds that the linkages between sectors (mining and the building construction industries) are closely related and heavily dependent on the world economic climate. What happens in the world economies will have an important bearing on how shocks are transmitted to the Australian resource industry and other sectors. The results provide evidence that changes in the economic trends can lead to changes in employment reallocation that affect labor mobility and flexibility.

Despite the highly cyclical nature of Australian mining employment, the employment activity in the building and construction industry presents another version of the story. As shown in Table 2 (i.e., 1.315), the results demonstrate that employment in the mining industry does have an impact on the building and construction industry. The empirical outcome of the use of elasticities is 563.934. Therefore, we strongly believe that there was no attraction of a large number of skilled mining workers to work in the building and construction industry since the mining boom drew to a close. Mining workers who become laid off or retrenched as a result of the shutdown of mining projects are more likely to move to other sectors, such as the energy, oil, and gas industry, as well as to the transport and warehousing industries.

The model in this study is based on our understanding of the current patterns of growth in mining employment in Australia in the different sectors (e.g., the building and construction industry). The empirical evidence provided in this study indicates that the movement of labor between the different sectors does occur in the Australian mining industry. Generally speaking, the movement of skilled laborers from the mining industry to other sectors can be cyclical and is more likely to occur during a downtrend in the mining cycle.

Understanding the shifts in sectoral employment between mining and other industries is important. The authors, therefore, calculate the growth rates of the six industries (mining, rental, hiring and real estate services, transport, postal and warehousing, agriculture, forestry, and fishing, and manufacturing) and then apply the growth rates them to estimate the Lilien index.Footnote 11 The study follows the Lilien index as explained in Ansari et al. (2013) to conduct an empirical analysis. The Lilien index in this study is analyzed using the periods of 1950q1–2018q4, which is different to that mentioned in the above Figs. 1–5. We believe that applying the data using the 1950s explains how the Australian economy transformed during these periods and how the employment activities shifted, especially to favor the resource and mining sectors, with the occurrence of the boom and bust cycles of Australian business.

Figure 6 depicts the sectoral employment mobility in the Australian resource and mineral industry. The figure shows the dimension of the sectoral employment for six industries in Australia since the 1950s. The shifts in sectoral labor mobility in the resource and mineral industry are reflected in the Australian labor market. This activity (the shifts of labor employment) is most likely to occur during periods of high volatility and uncertainty in the economy. Bloxham and Nash (2019) believe that the economic shocks in Australia usually come from overseas. In most cases, Australia’s post-war recessions coincided with global downturns.

In particular, our study shows that the highest sectoral shift of employment has been 8%. The findings show that the level of mobility of mining workers has been moderated and has remained at 0.352 even though the Australian economy has encountered significant turbulence from such as the GFC and foreign diplomatic conflicts (e.g., the US-China trade war and Brexit). We believe that the stability of the Australian economy could be a reason that has led to only a small percentage change in the shift of mining employment to other sectoral industries.

Moritz et al. (2017) employ data on the number of employees in selected non-mining sectors and mining sectors covering the relatively recent mining boom period (2003–2013). Their results show positive statistical relationships between increases in the number of employees in different sectors. The private sectors, including retail trade, transport, and hotels and restaurants, are most affected, while the industrial, business and government sectors also benefit from growth in mining.

By sharing the empirical analysis in Moritz et al. (2017), we argue that the growth of the mineral and resource industry in Australia can create more job opportunities for local communities, as well as for citizens across Australia. Nonetheless, changes in economic activities can also lead the sectoral shifts in mining employment activity. These findings have been shown in other similar studies (Hoffmann and Shi 2011; Mitkova and Dawid 2016; Mussida and Pastore 2012; Robson 2006).

Indeed, many mining workers and their families would rather not live in remote mining regional communities. The choice of where to live is often critical and this is a particularly important consideration for FIFO families who often prefer to live in the city; particularly once their children reach secondary school age. Other attributes, which make living in the city more attractive, include the greater diversity of employment opportunities available for young people once they finish school, more recreational and social activities, connections to other family members, and the ability to have a social life that is disconnected from the workplace.

Our study also evidences that the creation of job opportunities by mining companies because of the increase in LDC has led to changes in the governance of remote settlements. In other words, resource companies have become significant players in providing services and amenities for remote or host communities by including supporting medical and dental services, road maintenance, entertainment, school facilities such as playgrounds and reasonable housing costs. This support is important for mining companies to provide because it fills the gaps in service delivery in remote regional mining towns and ensures that towns being developed will be attractive to mining FIFO workers and their families.

We found that the empirical evidence relating to Australian mining employment is very sensitive, and there is much variability that creates turbulent results in terms of the world economy. However, the study by Abraham and Katz (1986) gave a picture of the US labor market where the job-creating sectors were more stable. Their findings demonstrate that information on job vacancies can be used to distinguish a pure sectoral shift from a pure characterization of aggregate demand.

Our study supports many of the findings of the existing literature. One such study is by Eriksson et al. (2016) who found that the presence of a strong specialization in the shipbuilding industry (similar to the mining industry) can lead to the majority of skilled workers remaining in the industry for as long as possible rather than moving to other industries, even during an industrial decline.Footnote 12 We believe that the presence of a related regional specialization (other than the mining industry), particularly at the end of a mining boom, is critical. Movement to related industries, where the skills and qualities of skilled mining workers are highly compatible, could offer another window of opportunity for those exiting the industry.

Conclusions

Using quarterly data, we have investigated the Australian labor market in the mineral industry and the mobility of mining workers that results from changing trends within the resource sector. The resource boom creates a shortage of skilled labor and leads mining companies to look for these workers from other sectors, while the high wage created by labor shortages draws these workers from across the industries in Australia through LDC arrangements such as FIFO. Additionally, recruiting resource sector workers can be challenging for mining companies who work hard to retain trained and experienced staff and our study addressed these problems encountered by many mining and resource companies. Our findings show that there is a sectoral shift in mining employment in Australia’s mineral and resource industry, particularly in the post-war period. Since then, the sectoral shifts of labor employment have remained moderate in the Australian mineral and resource industry. Therefore, this paper concludes that there is a strong indication that sectoral employment shifts between industries occur as a result of the evolution of the resource boom and bust periods.

Our empirical evidence illustrates that the resource sector or the mining industry is impacted and dominated by the world’s economic activities. The skilled labor movement between sectors can be the result of a shutdown of large-scale mining projects. New work arrangements, including new town construction and operation costs, restructuring in the minerals sector, changes in regulatory and political environments, labor supply, mobility and place preferences, have given rise to a new geography of resource development that is characterized by highly mobile workforces and a much broader spectrum of resource community types. In most cases, the workers’ transferable skills can be utilized in related industries, such as the building and construction industry, and the energy sector. Therefore, our findings conclude that it is important to recognize the existing connections between the mining industry, the regional community and the rest of the economy. A cyclical change in the mining cycle can affect the employability of its workers and related industries.

Mining represents a minor industry sector, but its social and economic contribution is strongly valued by the mining workers and by local government and community organizations. An important economic effect of LDC arrangements is that mining incomes enable mining workers, families, and businesses to remain in remote regional areas, regardless of the considerable distances from the mining activity. This evidence seems consistent with the view that cyclical labor movement between sectors is primarily related to fluctuations in the economy (e.g., GDP and other aggregate shocks). This has been seen in the mining sector and related industries, such as the building and construction industry. It has also been demonstrated that the fluctuation in business cycles is significantly correlated with employment activities in high-risk and volatile sectors. Our findings, therefore, provide useful in-depth mining labor analysis for the mining sector and government agencies in Australia, particularly in the mining states, such as Qld and WA. Additionally, these research outcomes provide clear explanations for the mining companies as well as public agencies both in the federal and states that the mobility of labor is an important element of policymaking. Since the labor mobility helps labor market adjustment — workers moving between industries and states. In other words, flexible policies help in accommodating and rehabilitating displaced workers due to economic cycles.

Notes

The data used to compute the Lilien index must be in log format.

During the gold rush of the 1850s, the population of Victoria increased from 77,000 to 540,000 within a 2-year period. Additionally, the mining boom in the past century has also been associated with a large increase in the population, especially in terms of inter-state migration. However, this growth is relatively minor compared with the current population base.

The researchers’ strong belief is that sectors such as agriculture, building and construction and manufacturing industries have greater cyclical sensitivity and are highly correlated with the mining industry.

The standard Dutch disease framework assumes that there are three relevant sectors: mining and manufacturing (both of which are traded internationally), and services (which are not traded). This theory also assumes that the average price level at home and abroad is a weighted average of traded and non-traded goods.

During a mining boom, there are two effects of the Dutch disease. First, the spending effect is a process in which there is an increase in world demand for a subset of the nation’s mineral exports and, subsequently, this leads to a currency appreciation that inversely impacts other non-booming industries. Second, the resource movement effect is a process in which labor and capital in the non-booming sectors are drawn out by the booming sector, leading to a further contraction in the manufacturing and service sectors, and a smaller expansion in the resource industry.

Despite its rapid growth over the decade, mining employment increased by only 110,000 (to approximately 200,000 or 1.7% of total employment). The mining industry only represents a small share of the 2.2 million increase in employment nationally (Connolly and Orsmond 2011).

In theory, the relationship between the cyclical fluctuations of the sectoral structures, as estimated by the Lilien Index and the unemployment rate, depends on the following features: (1) the extent to which industries differ in their trend rates of growth; (2) the potential effect of aggregate demand fluctuations on employment growth dispersions; and (3) the degree of labour force homogeneity, mobility and labour market imperfection (Garonna and Sica 2000).

The North American study, as presented by Abraham and Katz (1986), uses services and manufacturing sectors to develop the two-factor model. In fact, the objective of this study is to shed light on the labour mobility between sectors. Therefore, the energy, oil and gas, and mining industries are used in this two-factor model.

The study applies the mining labor and capital productivity indexes to estimate the movement of mining workers between jobs and the benefits obtained from the productive assets held by the industry e.g., equipment, machines, structures and vehicles.

This is supported by the mining industry’s average rate of growth, which is shown as 37.453.

See Ansari et al., 2013.

Our paper emphasizes the Australian sectoral employment mobility of mining workers shifting from one sector to another and shares similar conclusions to the study conducted in Eriksson et al. 2016. However, the study in Eriksson et al. 2016 emphasized labor movement and geography of two regions (the West German and Swedish cases).

References

Abraham KG, Katz LF (1986) Cyclical unemployment: sectoral shifts or aggregate disturbances? J Political Economy 94(3):507–522. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1833046

Anderson K (2018) Mining’s impact on the competitiveness of other sectors in a resource-rich economy: Australia since the 1840s. Miner Econ 31(1):141–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-017-0133-8

Ansari RM, Mussida C, Pastore F (2013) Note on Lilien and Modified Lilien Index. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). Discus Pap No 7198:1–9

Atkinson G, Hargreaves J (2014) An exploration of labour mobility in mining and construction: who moves and why. In, Department of Industry. Adelaide: National Centre for Vocational Educational Research.

Australia Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2021a) Catalogue Number: 8412.0:Mineral and Petroleum Exploration, Australia. Canberra

Australia Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2021b) Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly Catalogue Number: 6291.0.55.003. Canberra: ABS

Australian Government (2021) Regional Industry Data. Retrieved from: https://lmip.gov.au/default.aspx?LMIP/GainInsights/IndustryInformation/Mining

Australian Government (2022) The Australian resources sector - significance and opportunities. Retrieve from https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/australias-national-resources-statement/the-australian-resources-sector-significance-and-opportunities

Australian Treasury (2009) 2009–10 Budget Papers. Canberra: Australian Government. Refrieve from https://archive.budget.gov.au/2009-10/index.htm

Bachmann R, Burda M (2007) Sectoral transformation, turbulence, and labour market dynamics in Germany. SFB 649 Discussion Paper 2007–008. Bergische Universität Wuppertal, Germany Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany Berlin

Banks G (2011) Australia's mining boom: what's the problem? Paper presented at the The Melbourne Institute and The Australian Economic and Social Outlook Conference, Melbourne

Barsky RB, Kilian L (2004) Oil and the macroeconomy since the 1970s. J Econ Perspect 18(4) 115–134. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3216795. Retrieved from: http://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/0895330042632708

Basile R, Girardi A, Mantuano M, Pastore F (2011) Sectoral shifts, diversification and regional unemployment: evidence from local labour systems in Italy IZA Discussion Paper No. 6197

Battellino, R (2010) Mining booms and the Asutralian economy. Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, March quarter, pp 63–69

Bishop J (2019) Education choices and labour supply during the mining boom. RBA Bulletin, September, pp 20–27

Bloxham P, Nash T (2019) What if? QE downunder. HSBC Global Research, vol 14

Brueckner M, Durey A, Mayes R, Pforr C (2014) Resource curse or cure?: on the sustainability of development in Western Australia. Springer, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-53873-5

Cho J-O, Cooley TF (1994) Employment and hours over the business cycle. J Econ Dyn Control 18(2):411–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1889(94)90016-7

Connolly E, Lewis C (2010) Structural change in the Australian economuy. RBA Bulletin, Septermber Quarter. Available https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2010/sep/1.html#:~:text=Over%20time%2C%20the%20structure%20of,of%20Queensland%20and%20Western%20Australia

Connolly E, Orsmond D (2011) The mining industry: from bust to boom. Reserve Bank of Australia: Research Discussion Paper RDP 2011–08, December 2011

Corden WM, JP Neary (1982) Booming sector and de-industrialisation in a small open economy. Econ J 92(368):825–848

Corden WM (1984) Booming sector and dutch disease economics: survey and consolidation. Oxford Econ Pap 36:359–380

Cordes YK, Ostensson O, Toledano P (2016) Employment from mining and agricultural investments: how much myths, how much reality? Columbia University, July, Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment and the Earth Institute, p 2016

D'Arcy P, Gustafsson L, Lewis C, Wiltshire T (2012) Labour market turnover and mobility. Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, December Quarter. Available: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2012/dec/pdf/bu-1212-1.pdf

Debelle G, Vickery J (1998) The macroeconomics of Australian unemployment. Paper presented at the Unemployment and the Australian Labour Market, Canberra

Dietsche E (2020) Jobs, skills and the extractive industries: a review and situation analysis. Miner Econ 33(3):359–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-020-00219-2

Dixon R, Freebairn J (2009) Trends in regional specialisation in Australia. Australas J Reg Stud 15(3):281–296

Downes P, Louis C, Lay C (1997) Influences on the Australian Business Cycle.

Doyle M-A (2014) Labour movement during the resource boom Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, December Quarter. https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2014/dec/pdf/bu-1214-2.pdf

Ejdemo T (2013) Mineral development and regional employment effects in northern Sweden: a scenario-based assessment. Miner Econ 25(2):55–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-012-0023-z

Eriksson RH, Henning M, Otto A (2016) Industrial and geographical mobility of workers during industry decline: the Swedish and German shipbuilding industries 1970–2000. Geoforum 75:87–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.06.020

Evans R, Moore A, Rees DM (2019) The cyclical behaviour of the labour force participation rate in Australia. Aust Econ Rev 52(1):94–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8462.12308

Foo N, Bloch H, Salim R (2018) The optimisation rule for investment in mining projects. Resour Policy 55:123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2017.11.005

Fuentes FH, Garcia CJ (2016) The business cycle and copper mining in Chile. CEPAL Rev 118:157–181

Garonna P, Sica FGM (2000) Intersectoral labour reallocations and unemployment in Italy. Labour Econ 7(6):711–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-5371(00)00018-X

Gregory RG (2012) Dark corners in a bright economy: the lack of jobs for unskilled men. ABL 38(1):2–25

Goodman J, Worth D (2008) The mining boom and Australia’s resource curse. J Aust Polit Econ 61:201–219

Grudnoff M (2012) Job creator or job destroyer? An analysis of the mining boom in Queensland. The Australia Institute Policy Brief No. 36 March 2012 ISSN 1836–9014

Harding D (2002) The Australian business cycle: a new view. MRPA, Munich Personal RePEc Archive, MPRA Paper No. 3698

Haslam McKenzie F (2010) Fly-in fly-out: the challenges of transient populations in rural landscapes. In BR Luck G, Race D (Eds) Demographic Change in Australia's Rural Landscapes. Landscape Series, vol 12). Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9654-8_15

Haslam McKenzie F (2020) Long distance commuting: a tool to mitigate the impacts of the resources industries boom and bust cycle? Land Use Policy 93:103932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.03.045

Hereth S, Jayanthakumaran K (2020) Employment change in mining and manufacturing in Australia, 2010/11 - 2015/16: Dissecting the subnational patterns and concentrations. Faculty of Business and Law - Papers 13. http://ro.uow.edu.au/balpapers/13

Hicks J, Basu P, Sherley C (2014) The impact of employment specialisation on regional labour market outcomes in Australia. Australian Bulletin of Labour, National Institute of Labour Studies 40(1):68–90

Hoffmann F, Shi S (2011) Sectoral shift, job mobility and wage inequality. 2011 Meeting Papers 93, Society for Economic Dynamics

Kent C (2016) After the boom. Bloomberg Breakfast. Retrieved from: https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2016/sp-ag-2016-09-13.html

Lilien DM (1982) Sectoral shifts and cyclical unemployment. J Polit Econ 90(4):777–793. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1831352

Loungani P, Rush M, Tave W (1990) Stock market dispersion and unemployment. J Monet Econ 25(3):367–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(90)90059-D

Lucas RE, Prescott EC (1974) Equilibrium search and unemployment. J Econ Theory 7(2):188–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0531(74)90106-9

McKenzie F, Haslam McKenzie F, Hoath A (2014) Fly‐in/fly‐out, flexibility and the future: does becoming a regional FIFO source community present opportunity or burden?. Geogr Res 52(4):430–441

Measham TG, Haslam Mckenzie F, Moffat K, Franks DM (2013) An expanded role for the mining sector in Australian society? Rural Soc 22(2):184–194. https://doi.org/10.5172/rsj.2013.22.2.184

Merz M (1995) Search in the labor market and the real business cycle. J Monet Econ 36(2):269–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(95)01216-8

Minerals Council of Australia (2013) Georaphic labour mobility. Submission on the Productivity Commission's Issues Paper August 2013

Minerals Council of Australia (2021) Trade and investment. Retrieved from: https://www.minerals.org.au/trade-and-investment

Mitkova M, H Dawid (2016) An empirical analysis of sectoral employment shifts and the role of R&D. Innovation-Fuelled, Sustainable, Inclusive Growth ISI Growth Working Paper no. 27

Moritz T, Ejdemo T, Söderholm P, Wårell L (2017) The local employment impacts of mining: an econometric analysis of job multipliers in northern Sweden. Miner Econ 30(1):53–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-017-0103-1

Mowbray N, Rozenbes D, Wheatley T, Yuen K (2008) Changes in the Australian Labour Market over the economic cycle. Retrieved from Canberra

Mowbray N, Rozenbes D, Wheatley T, Yuen K (2009) Changes in the Australian labour market over the economic cycle. Australian FairPay Commission, Research Report no.9/09

Mussida C, Pastore F (2012) Is there a southern-sclerosis? Worker reallocation and regional unemployment in Italy. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), IZA Discussion Paper No. 6954

NAB Group Economics (2016) The evolution of mining employment. Retrieved from: http://business.nab.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Evolution-of-Mining-Employment1.pdf

Neelin J (1987) Sectoral shifts and Canadian unemployment. Rev Econ Stat 69(4):718–723. https://doi.org/10.2307/1935969

Plosser CI (1989) Understanding real business cycles. J Econ Perspect 3(3):51–77. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1942760

Rampellini K Veenendaal B (2016) Analysing the spatial distribution of changing labour force dynamics in the Pilbara. Retrieved from: http://WorldCat.org.database

Roarty M (2010) The Australian Resources Sector its contribution to the nation, and a brief review of issues and impacts. Australian Parliament House 23 September 2010

Robertson S, Argent N (2016) The potential value of lifecycle planning for resource communities and the influence of labour force mobility. In: Haslam McKenzie, F. (eds) Labour Force Mobility in the Australian Resources Industry. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2018-6_7

Robson M (2006) Sectoral shifts, employment specialization and the efficiency of matching: an analysis using UK regional data. Reg Stud 40(7):743–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400600959371

Robson A (2015) The Australian economy and economic policy during and after the mining boom. Economic Affairs 35:307–316

Storey K (2001) Fly-in/fly-out and fly-over: mining and regional development in Western Australia. Aust Geogr 32(2):133–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049180120066616

Taiwo O (2013) Employment choice and mobility in multi-sector labour markets: theoretical model and evidence from Ghana. Int Labour Rev 152(3–4):469–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1564-913X.2013.00189.x

Tonts M (2010) Labour market dynamics in resource dependent regions: an examination of the Western Australian goldfields. Geogr Res 48(2):148–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-5871.2009.00624.x

Tyers R, Walker A (2016) Quantifying Australia’s ‘three-speed’ boom. Aust Econ Rev 49(1):20–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8462.12130

Zakharia N (2020) Mining industry holds largest slice of Australian economy. Australian Mining. Available https://www.australianmining.com.au/news/mining-industry-holds-largest-slice-of-australian-economy/#:~:text=Australia%27s%20mining%20industry%20has%20delivered,The%20Australian%20Bureau%20of%20Statistics

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Foo, N., Salim, R. The evolution of mining employment during the resource boom and bust cycle in Australia. Miner Econ 35, 309–324 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-022-00320-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-022-00320-8