Abstract

This purely descriptive note discusses various aspects of world trade in minerals. It is not aimed at specialist mineral economists who may extract any detailed trade figures they require from the United Nations’ Comtrade database. Rather it is directed to all those who might use readily available aggregate data on minerals trade for broad analyses of the minerals industry. It starts from the most commonly quoted estimates of minerals trade before looking at some of the issues surrounding those measures and highlighting some of the pitfalls involved. It then examines both the product composition and geographical origins of minerals trade and how it has developed over the past half century. The concluding sections turn to a discussion of the merits and demerits of various measures of mineral dependence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Comtrade database allows the analysis of trade data on two bases, the Harmonised System and the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC). This note is based on the SITC, but there are common pitfalls in defining the scope of the minerals industry whichever basis is used. The next section delves into the data in some detail, as such burrowing is necessary to an understanding of the meaning and relevance of the aggregate measures. It is in no way a criticism of the World Bank or other providers of aggregate trade data, but rather an explanation of the data. The devil, as always, is in the detail. That may be well understood by specialist researchers into the minerals industry, but such rare individuals are not the target audience for this note.

Perhaps the most widely quoted broad measure of minerals trade in general discussion is that of the World Bank, as published, for example, in its World Development Indicators. This covers total exports in divisions 27 (crude fertilisers, minerals not elsewhere specified), 28 (metalliferous ores and scrap) and 68 (non-ferrous metals) of Revision 4 of the SITC. The first column of the upper portion of Table 1 shows the figures for 2016,Footnote 1 as recorded in the United Nations’ Statistical Division’s Comtrade.

The total of $525.2 billion excludes the exports of a number of mineral producing countries, such as Papua New Guinea and the Democratic Republic of Congo, for which Comtrade has no data.

Some commentators (for example, Ericcson and Lӧf 2017) widen the definition of mineral trade to include pearls, precious stones and non-monetary gold (divisions 667 and 971 of SITC Rev.4). The totals for these are substantial, as shown in the lower portion of Table 1 and their inclusion greatly increases the value of mineral exports to $985 billion in 2016.

An important caveat about using total exports as a measure is that they embrace re-exports as well as domestic exports. Re-exports are relatively insignificant for the narrower definition, accounting for little more than 2% of the published global total exports. They are far more important for precious stones and non-monetary gold, making up almost 20% of the total exports of these products. That means that re-exports account for just over 10% of the overall total shown in Table 1. In practice, re-exports are probably much greater than shown because many countries do not separately distinguish them. Looking beyond global figures, re-exports are important for some individual countries so that their inclusion can distort inter-country comparisons of export dependence. Domestic exports, as shown in the third column of Table 1, are a much cleaner measure, both for inter-country and for temporal comparisons.

The product composition of mineral exports

More importantly, the definition of minerals trade shown in Table 1, whether on the narrow or broader basis, includes a range of products that are not normally regarded as being produced by the minerals industry and excludes some significant products that clearly are. Table 2 shows the composition of the exports of ores and metals covered in divisions 27, 28 and 68, excluding the 2015 figures for the three countries given in Table 1. The upper portion of the table, with the items contained in subtotal A, gives the products of the mineral industry, and the lower portion, with subtotal B, other mineral products.

Whereas trade in iron and steel is not treated as coming from the minerals industry, the total of Table 1 rather illogically includes significant trade in ferrous waste and scrap. Trade in other forms of metalliferous waste and scrap, which is mainly engendered in minerals consuming rather than producing countries, is also included. Total exports of waste and scrap (divisions 282, 288 and 2892) amounted to $59.8 billion in 2016, and domestic exports to $59 billion. These exports are major sources of raw materials in some countries, often competing with virgin materials, but their inclusion can distort the data as indications of the contributions to economic activity from mining.

Division 68 of the SITC includes semi manufactures as well as primary metals. By far the greater share of these is produced in minerals consuming countries, and they are not normally treated as part of the mining and metals industry. This is most relevant for copper as semi manufactures make up 46% of the exports included in division 682. Aluminium (division 684), which accounts for 20% of the total domestic exports in the table, is a manufactured product based on the raw materials included in division 285. Its economics depend not just on mining but predominantly on the availability of low-cost energy. There is no more justification for including it than there would be for iron and steel and it is illogical that the former is included but the latter is not.

Table 2 shows that scrap, semimanufactures and aluminium make up two-fifths of its totals.Footnote 2 Whereas the overall trends in the two subtotals may, or may not be similar over time, measures of mineral dependency based on subtotal A are likely to differ considerably in many countries from measures based on the total of subtotals A and B.

Turning to precious stones and non-monetary gold, Table 3 shows the product composition of divisions 667 and 971. Again, these include products that are not strictly produced by the mining industry such as pearls (division 6671) and synthetic gemstones (division 6674). These are included in Table 3’s subtotal B.

Most diamonds are exported from the mining countries in unprocessed form and much of their added value comes from cutting and polishing elsewhere. The domestic exports of countries identified by the US Geological Survey as mining gem diamonds, and for which Comtrade publishes trade data, amounted to $16.2 billion.Footnote 3 The diamond exports of mining countries are separately distinguished in the top portion of Table 3. The domestic exports of the major diamond cutting countries of Belgium, India and Israel collectively account for $55.6 billion, or 81%, of the $68.5 billion of the domestic exports by remaining countries shown in the lower portion of Table 3. A further share comes from semi-manufactured stones in industrial nations. Domestic exports of other precious stones from mining countries are similarly overstated, but to nothing like the same extent as for diamonds.

The domestic exports of gold shown in Table 3 include a substantial quantity of trade in existing above-ground stocks as well as semi-manufactured forms. Switzerland, the UK, Hong Kong, Singapore and the United Arab Emirates supplied almost half the total domestic exports of $278.46 billion. After deducting the domestic exports of a further group of industrial countries without a significant gold mining industry, the exports of newly mined gold from mining countries were much nearer to $100 billion, the value separately distinguished in the top part Table 3. As a rough check, the total value of global gold production in 2016 was approximately $125 billion.Footnote 4 Some was exported in unprocessed form and is included in section 28 shown in Table 2, and some will have been retained in the producing countries.

In summary, only one-third of global domestic exports of precious stones and non-monetary gold (subtotal A in Table 3 or $121.42 billion) should be counted as exports of newly mined mineral products. That is just over 26% of the total exports of these products that are shown in Table 1.

Some significant mineral products are excluded from the definitions of mineral exports covered so far. Table 4 shows the possible contenders, of which the largest is coal. Coal, lignite and peat (divisions 321 and 322) are undeniably mineral products, with similar supply characteristics to other minerals. The inclusion of coke (division 325) is more debatable as most coke ovens are located in mineral consuming countries. Many of the chemicals of divisions 522 and 523 are the first-stage products of mining and are analogous to primary metals. So too are simple phosphatic and potassic fertilisers (divisions 5622 and 5623). Lime, building stone and cement (divisions 6611 to 6613) are also primary products of mining and quarrying, as are the manufactures of divisions 662 and 663 included in the table.

The products of division 66 are the only mineral products of many countries. The exclusion of those, as well as the other products listed in Table 4, from estimates of mineral exports used in international comparisons and in measures of dependence can bias any resulting conclusions.

Drawing the threads together, Table 5 shows the total exports of newly mined and first-stage processed mineral products. The rounded totals amount to $640 billion for all exports and $627 billion for domestic exports. These figures compare with the overall levels of $1182 billion for total exports of all the products included in Tables 2–4 inclusive, and $1081 billion of domestic exports, as shown in the last line of Table 5.

The last line of Table 5 may give an indication of the overall importance of all mineral products in world trade, but for the reasons given in the previous discussion, it tends to exaggerate the importance of export trade for mineral producing countries.

The relative importance of the different products can change dramatically over time with shifts in relative prices, although there is a broad tendency for prices of the major products to move in step in response to fluctuating business conditions.

The geographical origins of mineral exports

So much for the product composition of mineral exports in 2016. A substantial proportion of exports comes from only a few countries. This is illustrated in Table 6, which shows the leading exporters of the products listed in Tables 2–4. The top part of the table shows total exports of SITC sections 27, 28 and 68, the measure published in the World Bank’s World Development Indicators.Footnote 5 The middle portion gives the figures for subtotal A of Table 2 (i.e. excluding aluminium, semi-finished non-ferrous metals, and waste and scrap of all types), and the bottom portion contains figures for the wider definition of total mineral exports given in Table 5. This last excludes newly mined gold, because its geographical origins are unavailable.

Only countries with at least 2% of the relevant totals are included in the table. The 16 exporters in the top third of the table accounted for 65% of global trade, the 15 in the middle portion for 72% and the 12 in the bottom third also for 65%. Australia is by far the largest mineral exporter on any basis but the USA drops from second to seventh place between the broad and narrower definitions because it is a large exporter of aluminium and non-ferrous semi-manufactures. China’s importance increases when the wider definition of mineral trade is adopted. The inclusion of the countries for which 2016 statistics are not available would not dramatically alter the rankings. One interesting feature is the importance of countries like Germany, Japan, UK, Korea and the Netherlands whose mining industries are relatively unimportant, but which are major shippers of unwrought metals, including silver and platinum products.

Relative trends in mineral exports

The trend in world exports of ores and minerals between 1962 and 2016 is shown in money terms in Fig. 1. The underlying data are derived from the estimates of world merchandise exports, as published in World Development Indicators, multiplied by the shares of ores and metals in that trade taken from the same source.

Much of the growth from 2002 to 2012 and the subsequent decline reflected changes in prices rather than movements in the volume of trade. Attention tends to focus, however, not on trends in the absolute levels of world exports of ores and minerals but on their shares of total merchandise trade. Accordingly, Fig. 2 shows the share of exports of products in sections 27, 28 and 68 (of SITC Rev.3) in global merchandise exports, as published in the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. In the world as a whole, this was on an erratically declining trend from the late 1960s to the early 2000s. This development conditioned much analysis of, and thinking about, the role of mineral production and trade in economic development. Subsequently, the share rose in step with the surge in prices and output of the early 2000s onwards.

World exports of ores and metals as a % of total merchandise exports, 1962–2017. Source: World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TX.VAL.MMTL.ZS.UN.), derived from Comtrade database of the United Nations Statistical Division. Last updated June 26, 2018

Source: World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TX.VAL.MMTL.ZS.UN.), derived from Comtrade database of the United Nations Statistical Division. Last updated June 26, 2018.

This overall picture masks substantial variations in the experiences of individual exporting countries. Moreover, it relates exports of minerals to merchandise exports from all countries, regardless of whether or not they have any mineral exports. Figure 3 demonstrates the variety of experience with the trends in shares of the six major mineral exporting countries that collectively accounted for 49% of the total on the narrower definition of subtotal A of Table 2. The data for South Africa are incomplete.

Exports of ores and metals as a % of total merchandise exports of selected countries, 1962–2017. Source: World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TX.VAL.MMTL.ZS.UN.), derived from Comtrade database of the United Nations Statistical Division. Last updated June 26, 2018

Source: World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TX.VAL.MMTL.ZS.UN.), derived from Comtrade database of the United Nations Statistical Division. Last updated June 26, 2018.

None displayed exactly the same trend as the global average, although Chile’s trend is similar and several experienced rising shares from the early 2000s.

Moving from trends to cross-country comparisons, Fig. 4 shows the percentage shares of minerals in total domestic merchandise exports on the broad definition of total mineral exports from Table 5, but without the contribution of gold. It covers all the countries for which 2016 data are available whose mineral share exceeded 5%. Zambia, Guinea, New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea and the DRC also rank amongst the most mineral-dependent countries, but their data for 2016 are not available.

In many instances, the shares shown in Fig. 4 differ considerably from those published by the World Bank in World Development Indicators. This reflects both their different coverage of mineral trade and the use of different measures of total trade. The World Bank uses total exports whereas Fig. 3 is based on domestic exports, net of re-exports. Moreover, the World Bank uses an earlier classification of trade (SITC 3) than this paper (SITC 4). Table 7 compares the two measures for all countries whose shares of minerals exceeded 10% on the measure used in this paper.

In most, but not all, instances, the dependence on minerals is greater on the basis used in Fig. 4 than on the World Bank basis. Yet, although the share of minerals in total exports is widely used as an indicator of a country’s dependence on the mining industry, neither series may be the best measure. That is because the importance of trade varies considerably between countries. One may have a very high share of minerals in its exports but a low dependence on international trade, whereas another’s economy may rely heavily on trade as well as having a large share of mineral products in its exports. Accordingly, Fig. 5 shows the share of mineral exports, on the Fig. 4 basis, in gross domestic product (GDP) for the countries where the share exceeded 1.75% in 2016, and for which the data are available. Table 8 compares the two measures for the countries included in Fig. 4.

In general, the countries with the highest dependence of trade on minerals have a similarly high dependence for GDP; Botswana and Mongolia head both measures. The ordering changes, however, for many other countries. For example, Jamaican and Australian exports are heavily biased towards minerals, whereas their GDP is far less dependent on mineral exports.

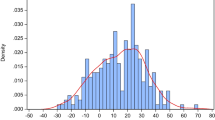

The relationship between the two indicators of dependence is summarised for all the countries for which data are available in the scatter diagram of Fig. 6. The two measures are naturally correlated, but the relationship is far from perfect, with an R2 of 0.77 in a simple linear regression.

Whilst the share of mineral exports in a country’s gross domestic product is one indicator of dependence on the mining industry, it is by no means a complete measure. First, some mineral products will be used domestically, particularly on the wider measure of minerals adopted in this paper. That means that export shares for the countries with domestic markets for their minerals will tend to understate their mineral dependence. Secondly, and probably more important for most mineral producing countries, export turnover is not a reliable guide to the value added by mining. Particularly in less developed countries, there will be various leakages through the mining industries’ imports of goods and services. Accordingly, Table 9 compares the share of mineral exports in GDP, as given in Table 8, with the percentage contributions of mining and quarrying to gross value added for selected countries in 2016.

Again, there are complications because some of the mineral products exported will be treated in National Accounts as products of manufacturing industry rather than of mining. More pertinently, mining and quarrying also embrace oil and gas production, which raises its share in some countries, like Australia, Bolivia and Peru. These qualifications aside, the table does demonstrate that the shares of exports in GDP can exaggerate the overall contribution of mining to economic activity.

Concluding remarks

This paper is merely descriptive. Its purpose has been to highlight some of the complexities involved in definitions of the minerals industry and to warn against unduly simplistic analyses of minerals trade and dependence. The mining industry embraces far more products than are included in sections 27, 28 and 68 of SITC Rev. 3, and those sections conversely include a wide range of products that are strictly beyond the purview of the mining industry. In consequence, much public debate is based on partial, and at times misleading, estimates of dependence.

There is clearly ample scope for comparative analysis of the relative merits and uses of different measures of mineral dependence. Such analysis might cover a much wider range of indicators than are included in this paper such as those used by the International Council on Mining and Metals in its Mining Contribution Index (ICMM 2010, 2014, 2016, 2018), or in the WIDER studies (Addison and Roe 2018; Roe and Dodd 2017; Ericsson and Lof 2017). Interesting though it might be, such analysis would probably be much more of academic interest than as a guide to policy. In any case, it is beyond remit of this note.

Notes

The table includes 2015 data for Guinea, New Caledonia and Zambia as their figures for 2016 have not yet (July 20, 2018) been included in the UN analyses. Their total exports amounted to $0.04 billion in division 27, $1.12 billion in division 28 and $5.17 billion in division 68.

Gem diamond production in 2015 as published in Table 11 of the gemstones chapter of the 2015 Minerals Yearbook, US Geological Survey (United States Geological Survey 2018)

Global output of 3221.6 t, and a spot price of $1248.6/ troy ounce in 2016, taken from World Metal Statistics 2018, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, Ware, 2018. There are 31,104 troy ounces in 1 t.

World Bank. 2017. World Development Indicators 2017. Washington, DC: World Bank.

References

Addison T & Roe AR (2018) Extractive industries: the management of resources as a driver of sustainable development. WIDER studies in development economics. Oxford University Press

Ericsson M & Löf O (2017) Mining’s contribution to low- and middle-income economies. WIDER Working Paper 2017/148. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER

International Council on Mining & Metals (ICMM), (2010) The role of mining in national economies, 1st edition, ICMM, London

International Council on Mining & Metals (ICMM), (2014) The role of mining in national economies, 2nd edition, ICMM, London

International Council on Mining & Metals (ICMM), (2016) The role of mining in national economies, 3rd edition, ICMM, London

International Council on Mining & Metals (ICMM), (2018) The role of mining in national economies, 4th edition, ICMM, London

Roe AR & Dodd S (2017) Dependence on extractive industries in lower-income countries: the statistical tendencies. WIDER Working Paper 2017/98. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER

United Nations National Accounts Statistics

United Nations Statistical Division, COMTRADE

United States Geological Survey (2018), Gemstones chapter of the 2015 Minerals Yearbook, US Geological Survey, Washington

World Bank (2018), World development indicators

World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TX.VAL.MMTL.ZS.UN.),

World Metal Statistics 2018 (2018), World Bureau of Metal Statistics, Ware.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Crowson, P. World minerals trade: a comment. Miner Econ 33, 183–192 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-019-00180-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-019-00180-9