Abstract

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic skin condition that significantly impacts patients’ quality of life. HS is often challenging to treat. In this review, we discuss the unique characteristics of HS in four special populations: children, the elderly, pregnant individuals, and breastfeeding mothers. In children, diagnosis may be delayed due to atypical and early HS disease presentations. HS management plans must take into consideration the lack of rigorous efficacy and safety data of HS treatments in this population. However, it is important to weigh the risk of treatments against the risk of untreated HS and the morbidity and mortality risk that having HS confers. Pregnancy poses unique challenges for women with HS, with their condition possibly worsening during pregnancy and increased risk of fetal death. Management strategies during pregnancy must consider both maternal and fetal safety. Similarly, breastfeeding mothers require thoughtful medication selection to balance symptom management with infant safety. In the elderly, HS may present more severely and is often complicated by comorbidities. Treating HS in this population should safely accommodate patients’ additional health conditions. Furthermore, this review highlights the overall paucity of primary literature addressing management in these populations, underscoring the need for further research to optimize HS care across all stages of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic skin condition that can have a profound negative impact on patients’ quality of life. Although most prevalent among people in their twenties and thirties, HS can present in adolescence or late adulthood. |

There is currently a lack of population-specific treatment guidelines for HS in children, pregnant and breastfeeding women, and the elderly. |

Management of HS in the pediatric population is largely modeled after adult guidelines and includes treatments such as topical agents, systemic antibiotics, hormonal and metabolic therapies, supplements, retinoids, biologics, small molecule inhibitors, and procedures. |

Although some HS medications should be avoided during pregnancy and lactation, there are medical and procedural treatment modalities that can be safely or cautiously used in these patients. |

Treatment of HS in the elderly should take into consideration the patient’s overall health, comorbidities, potential drug–drug interactions, and goals of care. |

Introduction

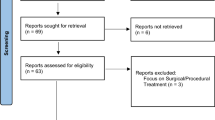

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, inflammatory disorder characterized by recurrent and painful nodules, abscesses, tunnels, and scarring that typically involve intertriginous areas [1]. Prevalence of HS is reported to be 0.1% in the USA [2] but is likely more common given frequent underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of this condition. Due to its chronic and debilitating nature, HS can profoundly negatively impact multiple aspects of a patient’s life. Patients with HS experience higher rates of unemployment, disability, pain, substance use, and mental health disparities [1, 3]. Timely diagnosis and intervention are critical in minimizing the burden of disease. Therefore, it is important that clinicians are prepared to diagnose and manage HS in all stages of life. Although HS has been found to be most prevalent among people in their twenties and thirties, up to 50% of patients with HS show symptoms between the ages of 10 and 21 years [4], emphasizing the need for improved early diagnosis of HS in the pediatric population. For a subset of patients, symptoms may manifest in late adulthood. Patients with HS have been found to have a lower life expectancy and higher all-cause mortality; chronic systemic inflammation may play a role [5,6,7]. Aggressive control of disease is essential, and consequences of untreated HS must be carefully weighed against risks of therapeutic interventions. There is a paucity of data on optimal management of HS in children, pregnant and breastfeeding women, and the elderly. This review discusses HS treatment strategies for the aforementioned special populations. Treatment strategies discussed are based on extrapolation from general HS literature as well as population-specific efficacy data wherever available. HS-specific drug safety data regarding use in these special populations is currently limited, thus safety conclusions also leverage existing literature regarding individual treatments used in these special populations for conditions other than HS. Herein, we aim to update clinicians on a practical approach to management of HS in these patients.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

HS in Children

HS affects approximately 28 out of 100,000 children and adolescents in the USA. When broken down, HS is quite rare under the age of 10 years and uncommon between ages 10 and 14 years. Of pediatric patients with HS, 72.4% are between the ages of 15 and 17 years [8], though underdiagnosis of HS in younger patients may skew prevalence data. Clinical presentation of HS in children can vary, leading to misdiagnosis and undertreatment of symptoms. Pediatric patients may present with subtle findings such as comedones, papules, pustules, and isolated cysts or abscesses [9]. As such, early disease is often misdiagnosed as acne, folliculitis, or infection. The chronic and recurrent nature of the skin lesions and their tendency to appear in intertriginous regions can help steer clinicians toward a diagnosis of HS. Average time from symptom onset to HS diagnosis is 2.5 years in the pediatric population [9], and up to 7 years in adults [10]. This lag time may contribute to worsening of symptoms and subsequent formation of irreversible skin damage. Clinicians should also assess for co-morbidities including psychiatric conditions (i.e. depression and anxiety), metabolic conditions (i.e. obesity, diabetes), polycystic ovarian syndrome, acne, atopic disease, asthma, and Crohn’s disease [11, 12]. Importantly, it is recommended to screen all patients with Down syndrome for HS given the increased risk of HS in this patient population [13].

Management of HS in the pediatric population is largely modeled after treatment guidelines for adults. There are currently no pediatric-specific HS treatment guidelines, and most systemic treatments are used off label in children, highlighting the need for further work in this area. Commonly utilized medications are listed in Table 1.

Approach to pediatric dosing can be challenging and has historically been determined by using one of the following methods: (1) age-based categories, (2) weight-based dosing, (3) use of body surface area, and (4) an allometric scaling method where physiological function is related to body size [14]. The Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy group recommends that weight-based dosing be utilized in patients under the age of 18 years who are less than 40 kg. Weight-based dosing should also be used in patients ≥ 40 kg, unless standard recommend adult dosing is surpassed [15]. Over 70% of pediatric patients with HS are 15–17 years of age [8], and thus are likely to require adult dosing for many medications. Of note, there is rising incidence of childhood obesity that can further complicate pediatric medication dosing, as it has been postulated that obese individuals may have decreased hepatic clearance and larger volume of distribution for lipophilic medications. Collaboration with a clinical pharmacist and pharmacokinetic analysis may be considered for overweight children to ensure safe and therapeutic dosing [15].

Topical Agents

Topical treatments may be considered first-line in milder disease states. Antiseptic washes such as chlorhexidine or benzoyl peroxide can be recommended for use in affected areas to help decrease bacterial load [12, 16]. Clindamycin 1% is the topical antibiotic of choice and can be used once to twice daily to active areas [17]. Resorcinol, a compounded topical keratolytic agent, may also be utilized as spot treatment twice daily to active lesions in pediatric patients with HS on the basis of promising efficacy in adults [18, 19].

Systemic Antibiotics

Systemic antibiotics may be utilized to address acute flares or as a bridge to more sustainable long-term therapeutics across all Hurley stages. Limited literature suggests that response rate to systemic antibiotics among pediatric patients is high [20]. Tetracyclines, such as doxycycline, can be utilized in patients over 8 years of age. They are generally not recommended in children under 8 years due to concerns for dental staining; however, more recent studies suggest that this age limit should be reconsidered if there may be substantial benefit to doxycycline use [21]. The combination of oral clindamycin and rifampin has been shown to be clinically effective in treating HS in pediatric populations [22]. Other systemic antibiotics that can be considered include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin, erythromycin, and metronidazole. Dapsone has been shown to improve disease in 9 out of 24 adults with HS, hypothetically due to its anti-inflammatory effects, but data on its use in pediatric patients with HS are limited [23]. Similarly, ertapenem, an intravenous beta-lactam antibiotic, has been efficacious as rescue treatment of adult HS, with little data on pediatric patients’ response [24].

Hormonal, Metabolic, and Supplement Therapies

Hormones likely play a role in HS pathogenesis, given onset of HS commonly occurs after puberty and for women; HS symptoms often flare with menses [25]. Modulating hormonal factors in adolescent patients, especially those undergoing puberty, can be helpful in managing HS symptoms across all severity levels. Finasteride, a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor, has been shown to reduce the frequency and severity of HS flares in female children in a few cases [26]. It is generally recommended to avoid finasteride use in males until after puberty. For post-menarche females over the age of 14 years, a combined oral contraceptive pill (OCP) or spironolactone may be used [27,28,29,30]. Pediatric female patients of childbearing age who are sexually active should undergo contraceptive counseling and adjunctive OCP if on finasteride or spironolactone, as these agents should be avoided during pregnancy. Metformin can be considered in pediatric patients with HS with milder disease or as an adjunct agent, particularly in patients with concomitant metabolic conditions such as obesity, type II diabetes mellitus, or insulin resistance. Several studies report improvement of pediatric HS on metformin, and a systemic review found metformin use to be relatively safe for managing obesity in children [20, 31, 32]. Additionally, oral zinc supplementation (90 mg/day) can be a useful and safe adjunctive therapy [33]. Low-dose copper should be co-administered, as zinc may deplete copper stores [34].

Retinoids

Consistent data suggesting efficacy of retinoids for HS is lacking; thus, they are only recommended as second- or third-line agents to consider for HS. Oral retinoids are best considered in patients with HS who have widespread comedones, a scarring folliculitis phenotype [35], or concomitant nodulocystic acne. Although the efficacy of isotretinoin has been inconsistent, younger age has been found to be associated with an improved response to isotretinoin [1, 36]. Two case reports suggest improvement of HS with acitretin use in adolescent boys with HS [37, 38].

Biologics

Adalimumab, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha inhibitor, is currently the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved biologic for pediatric HS in patients 12 years and older with moderate-to-severe disease. Secukinumab is an IL-17 inhibitor currently FDA-approved for treatment of moderate-to-severe HS in adults; however, it is approved for pediatric psoriatic arthritis down to the age of 2 years of age. Thus, it is reasonable to discuss secukinumab as a first- or second-line off-label treatment for pediatric HS on the basis of efficacy in adult clinical trials [39]. Dosing is weight dependent and typically lower than standard adult dosing. Infliximab, an intravenous TNF-alpha inhibitor, can be considered for severe or recalcitrant disease and is currently approved for treatment of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in patients aged 6 years and older. Several case studies demonstrate complete resolution or improvement of HS symptoms in adolescent patients while on infliximab therapy [40, 41]. A case series of 12 pediatric patients studied the efficacy of adalimumab, infliximab, and anakinra (an IL-1 antagonist) in treating HS. Results showed that 6 out of 7 patients who trialed infliximab, 4 out of 7 who trialed adalimumab, and the single patient who trialed anakinra achieved HS clinical response (HiSCR) after at least 4 months of treatment [41]. Ustekinumab, an anti-IL-12/IL-23 monoclonal antibody, is also recommended as a second-line agent in the North American Management Guidelines for HS [16]. One study of biologic use in children found that two patients treated with ustekinumab achieved complete resolution of HS symptoms without relapse within less than 12 months of therapy [42]. Ustekinumab is approved down to the age of 6 years for pediatric psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Anakinra, currently FDA-approved for treatment of IL-1 receptor antagonist deficiency, achieved HiSCR in a 15-year-old patient who had previously failed adalimumab and infliximab [41]. Although data on anakinra use for HS specifically in pediatric patients are limited, IL-1 inhibition may be considered as an alternative to those who have failed TNF and IL-17 inhibition.

Small Molecule Inhibitors

Oral small molecule inhibitors may be considered, especially for children who are unable to tolerate biologic injections. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, has been shown to improve HS abscess and nodule count in adults [43]. Although apremilast does not currently have an FDA indication for use in children, no new safety signals were identified when studied in pediatric patients with plaque psoriasis [44]. Upadacitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK) 1 inhibitor, is FDA-approved for atopic dermatitis in children down to the age of 12 years and phase 3 adult HS trials are currently underway [45, 46].

Procedures for HS

Surgical management of HS should be considered when patients present with HS flares or persistent HS lesions despite medical management. Surgical interventions can be implemented in conjunction with medical management, but patients’ age, tolerance for in-office procedures, and parental comfort should be considered. A systematic review of procedural treatments across 81 pediatric HS had showed favorable response. Reported procedures included as incision and drainage (I&D), deroofing, excisions, photodynamic therapy, botulinum toxin, laser treatments, hyperbaric oxygen, negative pressure wound therapy, and cryoinsufflation [47]. I&D can be performed to relieve acutely painful abscesses [18, 48]. Intralesional steroid injections have been found to be effective in treating acutely painful nodular lesions in patients with HS; strategies such as dilution with lidocaine 1% or application of topical lidocaine with distraction techniques should be implemented to help decrease anxiety regarding injections [12]. Surgical deroofing, excisions, and laser therapy have also been used for pediatric patients [18, 49].

HS in Pregnancy

HS disproportionately affects women of childbearing age [50, 51]. Thus, clinicians must be familiar with treatment options for HS that are considered compatible with pregnancy and breastfeeding. There appears to be considerable variability in HS disease activity during pregnancy. Although some patients may see improvement of their HS, most patients may experience unchanged or worsening disease activity during pregnancy and in the post-partum period [52, 53]. Furthermore, women with HS have been found to be at higher risk of adverse maternal, and pregnancy-related and neonatal outcomes, such as preterm birth or gestational hypertension, with HS being an independent risk factor for spontaneous abortion, gestational diabetes and cesarean section [54]. Women with HS have also been found to have lower likelihood of live birth and higher odds of elective termination [55]. Therefore, it is crucial that patients maintain regular follow-up appointments with both their dermatologist and obstetrician throughout their pregnancy. Prospective, large-scale studies are needed to determine the impact of HS treatments on pregnancy outcomes.

The FDA previously categorized medications into A, B, C, D, and X, with A signifying adequate human studies showing no risk to fetus and X defined as positive evidence of human fetal risk [56]. The pregnancy letter categories were recently replaced by the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule in 2015, as many providers found the letter classification to be confusing and overly simplistic; however, they are included in this review for historical reference. HS medications that are considered compatible, can be used with caution, or contraindicated in pregnancy are listed in Table 2.

Topical Agents

Antiseptic washes such as chlorhexidine wash and benzoyl peroxide wash are generally considered to be safe during pregnancy [57, 58]. Topical clindamycin 1% (Category B) can safely be recommended for pregnant women to treat active HS lesions [58].

Systemic Antibiotics

Systemic antibiotics for HS that are commonly prescribed by HS experts and generally considered safe to use during pregnancy include clindamycin (B), cephalexin (B), cefdinir (B), amoxicillin/clavulanate (B), and metronidazole (B) [59, 60]. Amoxicillin should be restricted to use in the second and third trimesters only due to potential risk of cleft lip and palate with exposure during the first trimester [61]. Although clindamycin is typically used in combination with rifampin, clindamycin monotherapy may have similar efficacy to combo therapy and thus is a reasonable treatment consideration [62].

Rifampin (C), dapsone (C), moxifloxacin (C), and ertapenem (B) should be used with caution during pregnancy. Rifampin should be considered on a case by case basis due to teratogenicity in animal studies and few reports of maternal and infant postnatal hemorrhage when used in the weeks preceding delivery and induction [63]. Tuberculosis consensus guidelines suggest that rifampin can be administered during pregnancy, thus clinicians may exercise use with caution when potential benefits outweigh risks [64]. Dapsone has not been associated with risk of congenital defects; however, cases of dose-related neonatal hemolysis [65] and hyperbilirubinemia [66] have been reported. While it is acceptable to use during pregnancy, it should be discontinued at least a month before birth to avoid kernicterus [66]. Moxifloxacin, a fluoroquinolone, has not been associated with a statistically significant increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes [67, 68]. Although there is limited human data, animal studies suggest increased risk of quinolone-induced arthropathy [69]. Intravenous ertapenem can be considered as rescue therapy for severe, recalcitrant HS [24]. Human safety data regarding ertapenem use during pregnancy are limited; however, animal studies suggest no developmental toxicity with fetal exposure of the drug. Mice exposed to drug in utero were found to have slight decreased fetal weight and decreased average number of ossified vertebrae [70]. Ertapenem may be used cautiously in scenarios where the clinical benefits outweigh risks.

Metabolic and Supplement Therapies

Metformin (B) can be utilized as adjunct therapy for HS in pregnant patients, especially in those with gestational diabetes. It is generally considered compatible with pregnancy, and two meta-analyses have not shown associated congenital abnormalities when taken during the first trimester [71, 72]. Zinc gluconate has also been shown to have therapeutic effects on HS, and is generally safe to use during pregnancy, although safety data is limited. Patients should be supplemented with low dose copper as excess zinc can deplete copper stores [34].

Biologics

Biologic safety data for treating of HS during pregnancy are limited, but many biologics have been tested in pregnant patients for other inflammatory conditions such as psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease. Adalimumab (B) and infliximab (B) have not been associated with significant pregnancy or neonatal complications [73]. There is general consensus that adalimumab and infliximab are considered safe during the first two trimesters of pregnancy, and that, with the increased transfer of IgG antibodies across the placenta at the beginning of the third trimester, a discussion should be had regarding continuation versus discontinuation [74]. Risk of fetal drug exposure versus the potential for uncontrolled disease with medication discontinuation must be taken into consideration. If TNF-inhibition is continued through delivery, live vaccines should be avoided for at least the first 6 months of the newborn’s life [75]. Certolizumab (B), a pegylated anti-TNF-alpha agent, is considered safe to use throughout pregnancy due to limited transfer of the medication across the placenta [76]. HS-specific safety and efficacy data for certolizumab is lacking and is currently limited to a few case reports [77,78,79].

There is currently a lack of safety data to recommend use of IL-17 agents such as secukinumab (B) during pregnancy. The Novartis Global Safety Database did not identify increased risk of spontaneous abortion, congenital malformation, or safety signals among 238 exposures, though only 153 outcomes were known. Pregnancy outcome data, especially with drug exposure during the second and third trimesters, are further limited, as a vast majority of patients discontinued secukinumab during their first trimester [80]. Ustekinumab (B), an IL-12/23 antagonist, has limited data in pregnancy as well. Data from the Pregnancy Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Neonatal Outcomes (PIANO) registry did not identify increased risk of spontaneous abortion or congenital malformations across 47 exposures. [81, 82]. Due to overall limited safety data, it is recommended that secukinumab and ustekinumab be considered only if a patient has failed or has a contraindication to TNF-alpha inhibition.

Small Molecule Inhibitors

There is limited human data on apremilast use in pregnancy. In animals, apremilast exposure during pregnancy has been associated with embryo-fetal death [83]. It is also recommended to avoid use of JAK inhibitors during pregnancy due to teratogenicity reported in animal studies [84].

Procedural Management

Major surgical procedures requiring sedation should be deferred until after delivery. However, in-office procedures including intralesional steroids and those that utilize local anesthesia are safe to perform during pregnancy. These procedures include local excision, incision and drainage, and de-roofing of sinus tracts. Local anesthesia is achieved with lidocaine (B) and is generally considered safe to use in pregnant individuals [85].

HS in Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding mothers with HS face unique challenges to both management of symptoms and safety of their child. Many patients experience postpartum flares, posing additional difficulties for these patients during a demanding time. Pain associated with HS, safety concerns regarding medications entering breastmilk, and concerns about their child coming into contact with HS can all impact a patient’s decision to breastfeed [86]. Clinicians should be familiar with the safety profile of HS therapies during lactation to minimize disruption of breastfeeding (Table 2).

Special Considerations for HS Treatment

Most medications safe to use in pregnancy are considered compatible during breastfeeding. Clindamycin is excreted into breast milk in small quantities and thus can be considered during breastfeeding; there is a small potential to disturb the gut microbiome in infants [87, 88]. Metronidazole can present in high concentrations in breast milk and should be discontinued 12–24 h prior to breastfeeding [89]. Rifampin is excreted into breast milk but has no adverse effects on infants. Therefore, it is safe to use in breastfeeding mothers with a similar caution with regards to its impact on the CYP-450 system [90]. Metformin is minimally excreted in breast milk and is generally safe to use in breastfeeding patients with HS [91]. Zinc does not enter breast milk; thus, it can be safely used [92].

Adalimumab and infliximab are both excreted in breast milk in negligible concentrations and are not well-absorbed through the gut; there have been no reported adverse effects on breastfeeding infants for either medication. Therefore, they are generally considered safe to prescribe during lactation [93]. Safety data on secukinumab and ustekinumab in breastfeeding are limited, but detection of these drugs in breast milk is expected to be low to minimal [94,95,96]. Apremilast and JAK inhibition should be avoided during lactation due to lack of human data [97].

HS in the Elderly

Geriatric HS is defined as the presence of active disease beyond the age of 65 years. The term “HS tarda” has been proposed and can be further subdivided in those with late onset and those with earlier onset and persistence into older age. The literature suggests a prevalence of 0.2% for late-onset HS and 0.8% for persistent HS in elderly individuals [98]. As in the adult population, elderly females are more commonly affected than elderly males. However, there was a higher proportion of males within the elderly HS population compared with the adult HS population (35.9% versus 22.8%) [98]. Overall, the female to male predominance is less in the older population compared with the adult population [99].

Literature suggests that HS can present more severely in elderly patients than their younger counterparts, and perhaps independent of overall disease duration [100,101,102]. Larger studies are needed to investigate for potential differences in clinical characteristics among those with late onset versus persistent HS. Elderly patients with HS are more likely to present with multiple comorbidities including hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, cardiac disease, renal disease, hepatic abnormalities, obesity, and tobacco use [98, 103, 104]. Thus, considering comorbidities is an important aspect of selecting appropriate therapies for older patients with HS.

Special Considerations for HS Treatment

Treatment of HS in the elderly population should take into consideration the overall health of the patient, as well as comorbidities, medications, and goals of care.

The topical therapies discussed in above sections are also standard of care for elderly patients with milder HS or as adjunct therapies [100, 103]. Choosing an optimal systemic antibiotic agent is contingent upon careful medication review to ensure no medication interactions, given polypharmacy is common in elderly patients [105]. Rifampin, for example, can decrease bioavailability of drugs metabolized by the cytochrome P-450 system, such as warfarin, digoxin, amiodarone, statins, β-blockers, and sulfonylureas [106].

Although there is no documentation on the efficacy of finasteride on older patients with HS, finasteride has been shown to be safe in postmenopausal women (those without a menstrual cycle for 12 consecutive months) and older men, and it may be an appropriate adjuvant therapy for HS in elderly patients. Metformin is also an option for patients with metabolic comorbidities to achieve control of both insulin resistance and HS [107]. If prescribing spironolactone to an elderly female patient, potassium levels should be closely monitored, especially in the setting of renal impairment [108]. Other medications requiring dose adjustment for patients with renal impairment include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cephalexin, ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, dapsone, ertapenem, metformin, and spironolactone [109]. Tetracyclines, azithromycin, rifampin, metformin, and acitretin should be avoided in those with severe hepatic impairment [110]. According to the American Geriatrics Society 2023 Beers Criteria, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, spironolactone, systemic estrogens, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs(NSAIDs), gabapentin, and opioids should be used with caution or avoided in the elderly [111].

Biologics including adalimumab, infliximab, secukinumab, and golimumab have been implemented as treatments for HS in the elderly [103]. TNF-inhibitors should be avoided in patients with a past medical history of class III or IV congestive heart failure [112]. There is currently limited evidence to guide clinicians on use of biologics in those with a history of malignancy. According to the joint American Academy of Dermatitis (AAD)-National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) psoriasis guidelines, TNF-inhibitors are typically contraindicated in individuals with history of lymphoreticular malignancy but can be considered in patients with a history of solid tumor malignancy who have failed other therapies [112]. The AAD-NPF psoriasis guidelines do not list history of lymphoreticular or solid organ malignancy as relative or absolute contraindications to IL-17 inhibition [112]. A retrospective study of 42 psoriasis patients with a history of prior malignancy found no increased likelihood of malignancy recurrence with IL-17 inhibition [113]. Biologic use in patients with a history of malignancy should be discussed with the patient’s oncologist, when possible, prior to initiation.

In-office procedures can be safely utilized for elderly patients as in the aforementioned populations. Procedures requiring general anesthesia should be considered on a case-by-case basis and require a multidisciplinary approach and thorough pre-operative evaluation. Elderly individuals are at increased risk of perioperative complications due to reductions in physiologic reserve, functional status, and coexisting diseases [114]. Thus, benefits and risks should be weighed, and use of in-office procedures should be implemented when feasible. Post-operative use of NSAIDs and opioids should be limited whenever feasible [111].

Conclusion

HS is an oftentimes debilitating disease for patients across different stages of life. However, certain demographic groups present with distinct management challenges that require additional considerations, particularly around medication safety. More research is needed to guide optimization of HS care for pediatric, pregnant, breastfeeding, and elderly patients, as HS data specific to these populations remains limited.

References

Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1045–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090.

Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, et al. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:760–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0201.

Delany E, Gormley G, Hughes R, et al. A cross-sectional epidemiological study of hidradenitis suppurativa in an Irish population (SHIP). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:467–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14686.

Hallock KK, Mizerak MR, Dempsey A, et al. Differences between children and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1095. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2865.

Tiri H, Jokelainen J, Timonen M, et al. Substantially reduced life expectancy in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a Finnish nationwide registry study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1543–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17578.

Egeberg A, GunnarH G, Hansen PR. Risk of major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:429–34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.6264.

Riis PT, Søeby K, Saunte DM, Jemec GBE. Patients with hidradenitis suppurativa carry a higher systemic inflammatory load than other dermatological patients. Arch Dermatol Res. 2015;307:885–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-015-1596-5.

Garg A, Wertenteil S, Baltz R, et al. Prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa among children and adolescents in the United States: a gender- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Investig Dermatol. 2018;138:2152–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2018.04.001.

Liy-Wong C, Kim M, Kirkorian AY, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in the pediatric population: an international, multicenter, retrospective, cross-sectional study of 481 pediatric patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:385. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.5435.

Saunte DM, Boer J, Stratigos A, et al. Diagnostic delay in hidradenitis suppurativa is a global problem. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1546–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14038.

Chang H-C, Lin C-Y, Guo Y-C, et al. Association between hidradenitis suppurativa and atopic diseases: a multi-center, propensity-score-matched cohort study. Int J Med Sci. 2024;21:299–305. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.90086.

Cotton CH, Chen SX, Hussain SH, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in pediatric patients. Pediatrics. 2023;151: e2022061049. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-061049.

Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059.

Bartelink IH, Rademaker CMA, Schobben AFAM, van den Anker JN. Guidelines on paediatric dosing on the basis of developmental physiology and pharmacokinetic considerations. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2006;45:1077–97. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200645110-00003.

Matson KL, Horton ER, Capino AC, Advocacy Committee for the Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy Group. Medication dosage in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther JPPT Off J PPAG. 2017;22:81–3. https://doi.org/10.5863/1551-6776-22.1.81.

Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.068.

Clemmensen OJ. Topical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with clindamycin. Int J Dermatol. 1983;22:325–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4362.1983.tb02150.x.

Riis PT, Saunte DM, Sigsgaard V, et al. Clinical characteristics of pediatric hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional multicenter study of 140 patients. Arch Dermatol Res. 2020;312:715–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-020-02053-6.

Katoulis A, Efthymiou O, Liakou A, et al. Resorcinol 10% as a promising therapeutic option for mild hidradenitis suppurativa: a prospective, randomized, open study. Skin Appendage Disord. 2023;9:438–43. https://doi.org/10.1159/000531926.

Masson R, Ma E, Parvathala N, et al. Efficacy of medical treatments for pediatric hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2023;40:775–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.15404.

Pöyhönen H, Nurmi M, Peltola V, et al. Dental staining after doxycycline use in children. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:2887–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkx245.

Bettoli V, Toni G, Odorici G, et al. Oral clindamycin and rifampicin in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa–acne inversa in patients of paediatric age: a pilot prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:216–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19867.

Yazdanyar S, Boer J, Ingvarsson G, et al. Dapsone therapy for hidradenitis suppurativa: a series of 24 patients. Dermatology. 2011;222:342–6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000329023.

Nosrati A, Ch’en PY, Torpey ME, et al. Efficacy and durability of intravenous ertapenem therapy for recalcitrant hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:312–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.6201.

Von Der Werth JM, Williams HC. The natural history of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:389–92. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00087.x.

Randhawa HK, Hamilton J, Pope E. Finasteride for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa in children and adolescents. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:732–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.2874.

Horissian M, Maczuga S, Barbieri JS, Zaenglein AL. Trends in the prescribing pattern of spironolactone for acne and hidradenitis suppurativa in adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:684–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.12.005.

Huang CY, Shah SA, Cochrane M, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa disease control associated with type of hormonal contraceptive use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2024;49:375–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ced/llad385.

Masson R, Park SE, Shih T, et al. Spironolactone in hidradenitis suppurativa: a single-center. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2024;10: e135. https://doi.org/10.1097/JW9.0000000000000135.

Svoboda RM, Nawaz N, Zaenglein AL. Hormonal treatment of acne and hidradenitis suppurativa in adolescent patients. Dermatol Clin. 2022;40:167–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2021.12.004.

Masarwa R, Brunetti VC, Aloe S, et al. Efficacy and safety of metformin for obesity: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2021;147: e20201610. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-1610.

Moussa C, Wadowski L, Price H, et al. Metformin as adjunctive therapy for pediatric patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Drugs Dermatol JDD. 2020;19:1231–4. https://doi.org/10.36849/JDD.2020.5447.

Offidani A, Molinelli E, Sechi A, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in a prepubertal case series: a call for specific guidelines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV. 2019;33(Suppl 6):28–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.15827.

Duncan A, Yacoubian C, Watson N, Morrison I. The risk of copper deficiency in patients prescribed zinc supplements. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68:723–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202837.

Bouwman K, Aarts P, Dudink K, et al. Drug survival of oral retinoids in hidradenitis suppurativa: a real-life cohort study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:905–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-022-00725-9.

Huang CM, Kirchhof MG. A new perspective on isotretinoin treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective chart review of patient outcomes. Dermatol Basel Switz. 2017;233:120–5. https://doi.org/10.1159/000477207.

Marzuillo P, Caiazzo R, Coppola C, et al. Polyclonal gammopathy in an adolescent affected by Dent disease 2 and hidradenitis suppurativa. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:e201–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.14789.

Chen A-W, Chen Z, Bai X-M, et al. Successful treatment of early-onset hidradenitis suppurativa with acitretin in an infant with a novel mutation in PSENEN gene. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2022;88:445. https://doi.org/10.25259/IJDVL_471_19.

Kimball AB, Jemec GBE, Alavi A, et al. Secukinumab in moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa (SUNSHINE and SUNRISE): week 16 and week 52 results of two identical, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 3 trials. Lancet Lond Engl. 2023;401:747–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00022-3.

Adams DR. Severe hidradenitis suppurativa treated with infliximab infusion. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1540. https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.139.12.1540.

Fougerousse A-C, Reguiai Z, Roussel A, Bécherel P-A. Hidradenitis suppurativa management using tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in patients younger than 18 years: a series of 12 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:199–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.071.

Sachdeva M, Kim P, Mufti A, et al. Biologic use in pediatric patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2022;26:176–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/12034754211049711.

Vossen ARJV, van Doorn MBA, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Apremilast for moderate hidradenitis suppurativa: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:80–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.046.

Fiorillo L, Becker E, de Lucas R, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast in pediatric patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: 16-week results from SPROUT, a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1232–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2023.11.068.

AbbVie. A phase 2, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study to evaluate upadacitinib in adult subjects with moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa. clinicaltrials.gov (2023).

AbbVie. A phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study to evaluate efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in adult and adolescent subjects with moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa who have failed anti-TNF therapy. clinicaltrials.gov (2024).

Masson R, Parvathala N, Ma E, et al. Efficacy of procedural treatments for pediatric hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2023;40:595–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.15331.

Lambert RA, Stein SL. Pediatric hidradenitis suppurativa: describing care patterns in the emergency department. Pediatr Dermatol. 2023;40:434–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.15231.

Leszczynska M, Diaz LZ, Peña-Robichaux V. Surgical deroofing in pediatric patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39:502–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.14955.

Cosmatos I, Matcho A, Weinstein R, et al. Analysis of patient claims data to determine the prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:412–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2012.07.027.

Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005.

Lyons AB, Peacock A, McKenzie SA, et al. Evaluation of hidradenitis suppurativa disease course during pregnancy and postpartum. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:681–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0777.

Seivright JR, Villa NM, Grogan T, et al. Impact of pregnancy on hidradenitis suppurativa disease course: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Basel Switz. 2022;238:260–6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000517283.

Fitzpatrick L, Hsiao J, Tannenbaum R, et al. Adverse pregnancy and maternal outcomes in women with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.023.

Sakya SM, Hallan DR, Maczuga SA, Kirby JS. Outcomes of pregnancy and childbirth in women with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:61–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.05.059.

Sachdeva P, Patel BG, Patel BK. Drug use in pregnancy; a point to ponder! Indian J Pharm Sci. 2009;71:1–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/0250-474X.51941.

McClure EM, Goldenberg RL, Brandes N, et al. The use of chlorhexidine to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity in low-resource settings. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;97:89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.01.014.

Kong YL, Tey HL. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs. 2013;73:779–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0.

Chien AL, Qi J, Rainer B, et al. Treatment of acne in pregnancy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29:254–62. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2016.02.150165.

Collier EK, Seivright JR, Shi VY, Hsiao JL. Pregnancy and breastfeeding in hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of medication safety. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34: e14674. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14674.

Lin KJ, Mitchell AA, Yau W-P, et al. Maternal exposure to amoxicillin and the risk of oral clefts. Epidemiol Camb Mass. 2012;23:699–705. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e318258cb05.

Caposiena Caro RD, Cannizzaro MV, Botti E, et al. Clindamycin versus clindamycin plus rifampicin in hidradenitis suppurativa treatment: clinical and ultrasound observations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1314–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.035.

Sanofi. rifadin.pdf. In: RIFADIN® Rx Rifampin Capsul. USP RIFADIN® IV Rifampin Inject. USP. https://products.sanofi.us/rifadin/rifadin.pdf (2024). Accessed 7 July 2024.

API Consensus Expert Committee. API TB consensus guidelines 2006: management of pulmonary tuberculosis, extra-pulmonary tuberculosis and tuberculosis in special situations. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:219–34.

Hocking DR. Neonatal haemolytic disease due to dapsone. Med J Aust. 1968;1:1130–1. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1968.tb29209.x.

Thornton YS, Bowe ET. Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia after treatment of maternal leprosy. South Med J. 1989;82:668. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007611-198905000-00037.

Ziv A, Masarwa R, Perlman A, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following exposure to quinolone antibiotics—a systematic-review and meta-analysis. Pharm Res. 2018;35:109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-018-2383-8.

Acar S, Keskin-Arslan E, Erol-Coskun H, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following quinolone and fluoroquinolone exposure during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Toxicol Elmsford N. 2019;85:65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2019.02.002.

Burkhardt JE, Hill MA, Carlton WW, Kesterson JW. Histologic and histochemical changes in articular cartilages of immature beagle dogs dosed with difloxacin, a fluoroquinolone. Vet Pathol. 1990;27:162–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/030098589002700303.

Merck. invanz_pi.pdf. In: INVANZ® Ertapenem Inject. https://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/i/invanz/invanz_pi.pdf (2022). Accessed 7 July 2024.

Gutzin SJ, Kozer E, Magee LA, et al. The safety of oral hypoglycemic agents in the first trimester of pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;10:179–83.

Gilbert C, Valois M, Koren G. Pregnancy outcome after first-trimester exposure to metformin: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:658–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.02.098.

Wang H, Hu Y, Chen F, Shen M. Comparative safety of infliximab and adalimumab on pregnancy outcomes of women with inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:854. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05191-z.

Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.087.

Nguyen GC, Seow CH, Maxwell C, et al. The Toronto consensus statements for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:734-757.e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.003.

Owczarek W, Walecka I, Lesiak A, et al. The use of biological drugs in psoriasis patients prior to pregnancy, during pregnancy and lactation: a review of current clinical guidelines. Adv Dermatol Allergol. 2020;37:821–30. https://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2020.102089.

Holm JG, Jørgensen A-HR, Yao Y, Thomsen SF. Certolizumab pegol for hidradenitis suppurativa: case report and literature review. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33: e14494. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14494.

Repetto F, Burzi L, Ramondetta A, et al. Certolizumab pegol and its role in pregnancy-age hidradenitis suppurativa. Int J Dermatol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.15742.

Wohlmuth-Wieser I, Alhusayen R. Treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with certolizumab pegol during pregnancy. Int J Dermatol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.15286.

Warren RB, Reich K, Langley RG, et al. Secukinumab in pregnancy: outcomes in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis from the global safety database. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:1205–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16901.

Chugh R, Long MD, Jiang Y, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in vedolizumab- and ustekinumab-exposed pregnancies: results from the PIANO registry. Off J Am Coll Gastroenterol ACG. 2024;119:468. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000002553.

Meyer A, Miranda S, Drouin J, et al. Safety of vedolizumab and ustekinumab compared with anti-tnf in pregnant women with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;S1542–3565(24):00010–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2023.12.029.

US Food and Drug Administration. 205437s006lbl.pdf. In: OTEZLA® Apremilast Tablets Oral Use. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/205437s006lbl.pdf (2017). Accessed 30 June 2024.

Akiyama S, Steinberg JM, Kobayashi M, et al. Pregnancy and medications for inflammatory bowel disease: an updated narrative review. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:1730–40. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i8.1730.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 006488s074lbl.pdf. In: Xylocaine Lidocaine HCl Inject. USP. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/006488s074lbl.pdf (2010). Accessed 30 June 2024.

Westerkam L, Masson R, Hsiao J, Sayed CJ. A survey-based study evaluating breastfeeding decisions and their impact on management in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1023–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2023.12.043.

Stéen B, Rane A. Clindamycin passage into human milk. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1982;13:661–4.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Clindamycin. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501208/. Accessed 15 Feb 2021.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Metronidazole. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501315/. Accessed 15 Sep 2023.

Chellappan. Dermatologic management of hidradenitis suppurativa and impact on pregnancy and breastfeeding. Cutis. 2022. https://doi.org/10.12788/cutis.0480.

Hale TW, Kristensen JH, Hackett LP, et al. Transfer of metformin into human milk. Diabetologia. 2002;45:1509–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-002-0939-x.

Perng P, Zampella JG, Okoye GA. Management of hidradenitis suppurativa in pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:979–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.032.

Fritzsche J, Pilch A, Mury D, et al. Infliximab and adalimumab use during breastfeeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:718. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0b013e31825f2807.

Balakirski G, Gerdes S, Beissert S, et al. Therapy of psoriasis during pregnancy and breast-feeding. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges J Ger Soc Dermatol JDDG. 2022;20:653–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.14789.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Ustekinumab. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500594/. Accessed 15 July 2024.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Secukinumab. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500738/. Accessed 15 Nov 2023.

Ibarra Barrueta O, García Martín E, López Sánchez P, et al. Biological and immunosuppressive medications in pregnancy, breastfeeding and fertility in immune mediated diseases. Farm Hosp. 2023;47:39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.farma.2022.12.005.

Van Der Weijden DAY, Koerts NDK, Van Munster BC, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa tarda: defining an understudied elderly population. Br J Dermatol. 2023;190:105–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjd/ljad317.

White JM, Del Marmol V. Hidradenitis suppurativa in the elderly: new insights. Br J Dermatol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjd/ljad378.

Antonelli F, Ippoliti E, Rosi E, et al. Clinical features and response to treatment in elderly subjects affected by hidradenitis suppurativa: a cohort study. J Clin Med. 2023;12:7754. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12247754.

Jiang SW, Petty AJ, Jacobs JL, et al. Association between age at symptom onset and disease severity in older patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2023;188:555–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjd/ljac121.

Nielsen VW, Ring HC, Holgersen N, Thomsen SF. Elderly male patients with hidradenitis suppurativa have more severe disease independent of disease duration. Br J Dermatol. 2024;190:292–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjd/ljad411.

Blum FR, DeBarmore BM, Sayed CJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa in older adults. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:216. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.5390.

Wei C, Mustafa A, Strange J, et al. Association of chronic kidney disease with hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective study. JAAD Int. 2024;15:36–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdin.2023.12.005.

Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:57–65. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2013.827660.

Soraci L, Cherubini A, Paoletti L, et al. Safety and tolerability of antimicrobial agents in the older patient. Drugs Aging. 2023;40:499–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-023-01019-3.

Hambly R, Kearney N, Hughes R, et al. Metformin treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: effect on metabolic parameters, inflammation, cardiovascular risk biomarkers, and immune mediators. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:6969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24086969.

Butler JV, McAvoy H, McEnroy D, Mulkerrin EC. Spironolactone therapy in older patients—the impact of renal dysfunction. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;35:45–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-4943(01)00214-x.

Munar MY, Singh H. Drug dosing adjustments in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(10):1487–1496.

Amarapurkar DN. Prescribing medications in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Int J Hepatol. 2011;2011: 519526. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/519526.

By the 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7):2052–2081.

Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057.

Pellegrini C, Esposito M, Rossi E, et al. Secukinumab in patients with psoriasis and a personal history of malignancy: a multicenter real-life observational study. Dermatol Ther. 2022;12:2613–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00797-9.

Baquero GA, Rich MW. Perioperative care in older adults. J Geriatr Cardiol JGC. 2015;12:465–9. https://doi.org/10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2015.05.018.

US Food and Drug Administration. 018662s059lbl.pdf. In: ACCUTANE® Isotretinoin Capsul. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/018662s059lbl.pdf (2008). Accessed 7 July 2024.

Provini LE, Stellar JJ, Stetzer MN, et al. Combination hyperbaric oxygen therapy and ustekinumab for severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:381–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.13775.

Paller AS, Ladizinski B, Mendes-Bastos P, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib treatment in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: analysis of the measure up 1, measure up 2, and AD up randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:526–35. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.0391.

Bookstaver PB, Bland CM, Griffin B, et al. A review of antibiotic use in pregnancy. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35:1052–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1649.

Vauzelle C. Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid in late pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2022;50:205–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gofs.2021.12.008.

Daniel S, Doron M, Fishman B, et al. The safety of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid use during the first trimester of pregnancy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:2856–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.14118.

Sheehy O, Santos F, Ferreira E, Bérard A. The use of metronidazole during pregnancy: a review of evidence. Curr Drug Saf. 2015. https://doi.org/10.2174/157488631002150515124548.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Cephalexin. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501487/. Accessed 18 Jan 2021.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Cefdinir. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501314/. Accessed 31 Oct 2018.

Benyamini L, Merlob P, Stahl B, et al. The safety of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and cefuroxime during lactation. Ther Drug Monit. 2005;27:499–502. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ftd.0000168294.25356.d0.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Rifampin. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501348/. Accessed 15 Oct 2023.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Ertapenem. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501585/. Accessed 18 Apr 2022.

Hyer S, Balani J, Shehata H. Metformin in pregnancy: mechanisms and clinical applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1954. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19071954.

Thatcher SS, Jackson EM. Pregnancy outcome in infertile patients with polycystic ovary syndrome who were treated with metformin. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1002–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.047.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Spironolactone. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501101/. Accessed 15 Nov 2023.

Glueck CJ, Salehi M, Sieve L, Wang P. Growth, motor, and social development in breast- and formula-fed infants of metformin-treated women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Pediatr. 2006;148:628–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.01.011.

Clowse MEB, Scheuerle AE, Chambers C, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after exposure to certolizumab pegol. Arthritis Rheumatol Hoboken NJ. 2018;70:1399–407. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40508.

Matro R, Martin CF, Wolf D, et al. Exposure concentrations of infants breastfed by women receiving biologic therapies for inflammatory bowel diseases and effects of breastfeeding on infections and development. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:696–704. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.040.

Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Katz L, et al. Adalimumab level in breast milk of a nursing mother. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:475–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2009.11.023.

Grosen A, Julsgaard M, Kelsen J, Christensen LA. Infliximab concentrations in the milk of nursing mothers with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:175–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.003.

Steen JS, Stainton-Ellis DM. Rifampicin in pregnancy. Lancet Lond Engl. 1977;2:604–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91447-7.

Padberg S, Wacker E, Meister R, et al. Observational cohort study of pregnancy outcome after first-trimester exposure to fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4392–8. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02413-14.

Sanders SW, Zone JJ, Foltz RL, et al. Hemolytic anemia induced by dapsone transmitted through breast milk. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:465–6. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-96-4-465.

Gürpinar AN, Balkan E, Kiliç N, et al. The effects of a fluoroquinolone on the growth and development of infants. J Int Med Res. 1997;25:302–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/030006059702500508.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Moxifloxacin. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501040/. Accessed 15 July 2024.

Passmore CM, McElnay JC, Rainey EA, D’Arcy PF. Metronidazole excretion in human milk and its effect on the suckling neonate. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;26:45–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.1988.tb03362.x.

Burmester GR, Landewé R, Genovese MC, et al. Adalimumab long-term safety: infections, vaccination response and pregnancy outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:414–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209322.

Saavedra MA, Romo-Rodríguez R, Gutiérrez-Ureña SR, et al. Targeted drugs in spondyloarthritis during pregnancy and lactation. Pharmacol Res. 2018;136:21–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2018.08.009.

Duran B, Gursoy S, Cetin M, et al. The oral toxicity of resorcinol during pregnancy: a case report. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2004;42:663–6. https://doi.org/10.1081/clt-200026966.

Vennila V, Madhu V, Rajesh R, et al. Tetracycline-induced discoloration of deciduous teeth: case series. J Int Oral Health JIOH. 2014;6:115–9.

Prakash O, Mathur GP, Kushwaha KP, Singh YD. Drug exposure in pregnant and lactating mothers in periurban areas. Indian Pediatr. 1990;27:1301–2.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Tetracycline. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501108/. Accessed 23 Feb 2021.

Liszewski W, Boull C. Lack of evidence for feminization of males exposed to spironolactone in utero: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1147–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.023.

BinJadeed HF, Alajlan A. Pregnancy and neonatal outcome with maternal exposure to finasteride: case series. J Dermatol Dermatol Surg. 2021;25:84. https://doi.org/10.4103/jdds.jdds_33_21.

Mother To Baby | Fact Sheets [Internet]. Brentwood (TN): Organization of Teratology Information Specialists (OTIS); 1994-. Finasteride. 2022 Oct. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK582707/.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 211675s003lbl.pdf. In: RINVOQ® Upadacitinib. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/211675s003lbl.pdf (2022). Accessed 7 July 2024.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Upadacitinib. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK561138/. Accessed 18 Jan 2021.

Lloyd ME, Carr M, Mcelhatton P, et al. The effects of methotrexate on pregnancy, fertility and lactation. QJM Int J Med. 1999;92:551–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/92.10.551.

Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Methotrexate. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501341/. Accessed 15 Dec 2023.

Acknowledgements

Author Contribution

Claire S. Chung, Sarah E. Park, Jennifer L. Hsiao, and Katrina H. Lee contributed to drafting of the manuscript. Jennifer L. Hsiao and Katrina H. Lee contributed to concept and design.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Jennifer L. Hsiao is on the Board of Directors for the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation; has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Aclaris, Boehringer Ingelheim, Incyte, Novartis, and UCB; has acted as a speaker for AbbVie, Novartis, Sanofi Regeneron, and UCB; and has served as an investigator for Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Incyte. Claire S. Chung, Sarah E. Park, and Katrina H. Lee have nothing to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, C.S., Park, S.E., Hsiao, J.L. et al. A Review of Hidradenitis Suppurativa in Special Populations: Considerations in Children, Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women, and the Elderly. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-024-01249-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-024-01249-2