Abstract

Actinic keratosis (AK) is an intraepithelial condition characterized by the development of scaly, erythematous lesions after repeated exposure to ultraviolet radiation. Significant immunosuppression is a risk factor for the development of AK and subsequent lesion progression to squamous cell carcinoma. Immunocompromised patients (ICPs), particularly organ transplant recipients, often have more advanced or complex AK presentations and an increased risk of skin carcinomas versus non-ICPs with AK, making lesions more difficult to treat and resulting in worse treatment outcomes. The recent “Personalising Actinic Keratosis Treatment” (PAKT) consensus reported that delivering patient-centric care may play a role in supporting better clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction with treatments for chronic dermatologic conditions such as AK, which require repeated cycles of treatment. Additionally, currently published guidance and recommendations were considered by the PAKT panel to be overly broad for managing ICPs with their unique and complex needs. Therefore, the “Personalising Actinic Keratosis Treatment for Immunocompromised Patients” (IM-PAKT) panel was established to build upon general recommendations from the PAKT consensus. The panel identified current gaps in guidance for AK care in ICPs, offered practical care approaches based on typical ICP scenarios, and highlighted the need to adapt AK management to optimize care and improve treatment outcomes in ICPs. In particular, dermatologists should establish collaborative and transparent relationships with patients’ multidisciplinary teams to enhance overall care for patients’ comorbidities: given their increased risk of progression to malignancy, earlier assessments/interventions and frequent follow-ups are vital.

The panel also developed a novel “triage” tool outlining effective treatment follow-up and disease surveillance plans tailored to patients’ risk profiles, guided by current clinical presentation and relevant medical history. Additionally, we present the panel’s expert opinion on three fictional ICP scenarios to explain their decision-making process for assessing and managing typical ICPs that they may encounter in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is a need to tailor management recommendations for immunocompromised patients (ICP) with actinic keratosis (AK), as they have a significantly increased risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma versus non-ICPs with AK. |

The “Personalising Actinic Keratosis Treatment for Immunocompromised Patients” (IM-PAKT) panel has provided their expert opinion on management recommendations for three fictional ICP scenarios to highlight specific aspects that should be addressed when treating typical ICPs with AK. |

Updated management recommendations for ICPs with AK should include guidance on risk stratification for ICP subgroups, information to be communicated to patients during consultations, and treatment options that are compatible with factors specific to ICPs (e.g., immunosuppressive regimens). |

Dermatologists should promptly assess ICP cases by individual risk factors and ensure open communication with patients’ wider multidisciplinary teams to personalize management strategies and remain informed about overall care plans. |

Introduction

An actinic keratosis (AK) is a scaly, erythematous, intraepithelial lesion that can develop after chronic, repeated exposure of the skin to ultraviolet (UV) radiation [1,2,3]. The development of AK lesions is often associated with keratinocyte carcinoma (KC) diagnosis, particularly invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) [4,5,6]. Immunocompromised patients (ICPs)—including those with an autoimmune or oncological condition, or those receiving chemotherapy or chronic immunosuppressive medication for organ transplantation—have a significantly increased risk of developing SCC versus the general population [3, 4]. In particular, organ transplant recipients (OTRs) have a 65–250-fold increased incidence of SCC [7, 8]; SCC metastasis occurs in 8% of cases, which contributes to 5% of mortality among OTRs [9]. AK lesions in ICPs can be more difficult to manage as they are often aggressive, complex, and more likely to progress to cutaneous malignancies [10]. Furthermore, conventional AK treatments that target either individual lesions or multiple AKs in a surrounding area of photodamaged skin (the “field of cancerization”) are less effective in ICPs compared with immunocompetent patients [3, 11, 12]. The challenges of managing more severe and hard-to-treat disease, and the increased risk of ICPs with AK developing KCs versus the general population may heavily impact patients’ quality of life. This may be because of greater physical disease symptoms (e.g., chronic itching and burning), more extensive side effects from repeated rounds of treatment, a greater psychological burden arising from increased fear of skin cancer development, or worse cosmetic outcomes [2, 13].

Delivering patient-centric care may play a role in supporting better clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction with treatments [2], especially for chronic dermatological conditions such as AK, which require repeated cycles of treatment [14, 15]. The recent “Personalising Actinic Keratosis Treatment” (PAKT) consensus developed expert recommendations and a novel clinical tool for the optimal, personalized care of general AK patients, emphasizing the need for shared decision-making between physicians and patients throughout the AK journey [16]. It aimed to improve education on the chronic, recurrent nature of AK and the necessity for long-term treatment follow-up and disease surveillance [16]. The PAKT project has put forward some consensus recommendations pertinent to ICPs; however, a need persists for more tailored and comprehensive insights, such as recommendations of factors to consider when selecting treatments for this patient population. Further understanding of how to improve personalized care approaches for ICPs would help reduce the elevated risk of AK progression to SCC and address the high disease burden.

Building on the PAKT consensus, the “Personalising Actinic Keratosis Treatment for Immunocompromised Patients” (IM-PAKT) panel was established to identify current unmet needs in AK care for ICPs and develop expert opinion on practical care approaches for typical ICP scenarios. Moreover, the article will refine the PAKT clinical tool to capture key steps in the ICP journey that warrant decision-making tailored to patients’ individual preferences and profiles.

Methods

IM-PAKT Expert Panel

This European panel comprised eight expert dermatologists, with established experience of treating ICPs with AK, from Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland and the UK. Two co-chairpersons oversaw the process and were involved in panel selection.

Literature Search and Panel Meeting

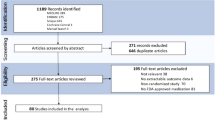

An initial literature search was conducted to review various aspects of current guidance, including tailoring AK management for ICPs (e.g., prevention and treatment of lesions and/or field cancerization), barriers to effective treatment, and reported patient goals/preferences and how these differ compared with the general population. Additionally, guidance on symptom monitoring, surveillance, and treatment adjustments following clinical review were assessed in regard to long-term AK care. PubMed was used to search MEDLINE articles published between 1 January 2010 and 7 March 2023 using terms designed to review aspects of AK management in ICPs (e.g., “immunocompromised,” “guidelines,” “prevention,” “treatment factors,” “monitor”). References were excluded if studies were performed in nonhumans/in vitro/ex vivo, they did not contribute to the research questions, or the abstract was unavailable. From the resulting 425 articles, additional searches were performed to replace secondary citations with primary sources and search recent guidelines; a total of 55 unique publications were selected. An interim hybrid panel meeting was conducted to review the results of the literature search, identify further gaps in care, and discuss potential ways to improve treatment outcomes.

Patient Scenarios

The general recommendations from PAKT were considered to be overly broad for managing ICPs with their unique and complex needs. The panel identified the need for patient scenarios to illustrate their care approaches and explain their decision-making process when managing typical ICPs that dermatologists may encounter during clinical practice. The panel were presented with three fictional yet typical ICP scenarios and asked to provide written feedback on how they would optimally manage each case.

Ethical Approval

Information presented in this article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any data from new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Expert Insights on Current Care Limitations

The panel identified several areas of limitation in current care strategies that warrant a need for updated AK management guidance [3, 10, 17,18,19,20].

ICP Classification and At-Risk Individuals

Firstly, the panel suggested a shift in mindset for the classification of ICPs; for example, not limiting classification to patients experiencing iatrogenic immunosuppression (e.g., with JAK inhibitors or chemotherapies such as hydroxyurea). The panel suggested that patients with weakened immunosurveillance because of natural causes, such as immunosenescence, should also be considered as ICPs [21]. Immunosenescence can arise because of several reasons, including thymic involution causing decreased production of new T cells, increased levels of senescent innate and adaptive immune cells that have reduced function or are inert, or persistent inflammation contributing to reduced adaptive immune response, tissue damage and age-related diseases (“inflamm-aging”) [22].

Occupations that may require an individual to spend a prolonged period of time outdoors are absent from current guideline risk factors. Exposure to UV radiation is the primary cause of AK [23], so occupations that increase this risk should be identified and cautioned against for all patients, but particularly ICPs.

ICP-Specific Factors for Effective Management

The panel noted that guidelines lack treatment recommendations that specifically address factors relevant to ICPs, such as type of immunosuppression or, for OTRs, the immunosuppressive therapy regimen. For example, immunosuppression because of long-term treatment with hydroxyurea or JAK inhibitors can lead to field carcinogenesis, which should be acknowledged and addressed in guidelines for AK management [24, 25]. Additionally, current prevention strategies are designed for the general patient population, making it difficult to tailor them specifically for ICPs. Alongside this, guidance is lacking on effective collaboration between dermatologists and other specialists such as transplant physicians or oncologists, which can be essential to ensure comprehensive and integrated care.

Systemic Barriers to ICP Care

There is also a need to address barriers related to education on managing AK and its chronicity for ICPs, their caregivers, dermatologists, and primary care physicians. To improve outcomes for this patient subgroup, it is vital to establish targeted educational programs and resources that focus on the prevention, early detection, and effective management of AK in ICPs. By ensuring that all stakeholders are well informed about the risks of prolonged UV radiation exposure, the importance of sun protection, and the need for regular clinical and self-skin examinations, treatment satisfaction and disease outcomes can be improved.

Additionally, the panel noted that a “call to action” to support optimal delivery of care for ICPs with AK should be implemented. This initiative should advocate for increased accessibility to treatment modalities, such as topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), tirbanibulin, or photodynamic therapy (PDT) that can be specifically tailored to ICPs [9, 26]. The development of new AK therapies tailored to ICPs should also be supported, for example, by advocating for future studies to include ICPs in the treated population. The panel also identified that a sequential approach to management with multiple modalities is often required, as no one treatment is deemed to be the most suitable [18]. By enhancing availability of effective treatments/combinations and incorporating these into patients’ management plans, it is hoped that current care limitations can be eliminated so ICPs can receive more effective and individualized treatment for AK.

Moreover, most current healthcare systems are unable to provide optimal care to ICPs with AK, which can exacerbate the challenges associated with their specialized needs. Patient overload leads to extended waiting times for appointments with dermatologists, not only heightening anxiety for ICPs with AK, but also increasing the risk of disease progression and potential complications of treatment. The strain on healthcare resources highlights the urgent need for improvements to the system, streamlined referral processes, and enhanced collaboration between healthcare providers.

Panel Commentary on Personalized Care Strategies

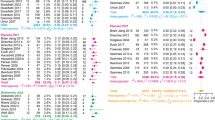

The PAKT clinical tool, as shown in Fig. 1, was developed to facilitate personalized care for the general population of patients with AK [16]. The IM-PAKT panel identified the following recommendations to build on the PAKT practical tool to support better treatment outcomes for ICPs.

Overview of the PAKT patient journey flowchart for the management of mild/moderate actinic keratosis (AK) on the face and scalp. Reprinted with permission from Morton C, et al. and MJS Publishing [16]. *Including coprescriptions and adjunctive therapies. SCC squamous cell carcinoma

When entering into the patient pathway as shown in Fig. 1, dermatologists must first establish the reasons for the patient’s immunocompromised status as this may impact how they enter the care pathway. Dermatologists should also create and maintain strong communication networks with all physicians in the patient’s wider multidisciplinary team (MDT), as understanding the motivations of the various physicians involved in the patient’s overall care is essential. For example, some practices may have dedicated transplant clinics that provide regular engagement between OTRs, their transplant team, and dermatologists within a defined care protocol. Additionally, while concerns about organ rejection, infections, and the potential onset of any cancer type typically take precedence for OTRs, it is essential that health care providers (HCPs) clearly communicate the elevated risk of AK development either before or soon after a transplant. This differs from non-OTR ICPs, who may only be referred after a diagnosis of AK or SCC, rather than at the point when they become immunocompromised. Additionally, the panel highlighted that dermatologists should always be prepared for first-time referrals of ICPs at greater risk (preexisting AK lesions and/or evidence of SCC).

The assessment and prioritization of ICPs should involve a strategic focus on effective management, especially for those at greater risk. To prevent the development of malignancy, early assessments and interventions that can facilitate a more aggressive management plan would be beneficial [8, 27]. Proactive, pretransplant dermatologist consultations for OTR patients would offer valuable insights into their initial skin condition to help determine individual risks of AK and SCC [9, 28], as well as any comorbidities that are likely to increase this risk further (e.g., cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, smoking). A patient’s risk profile should be continuously assessed at each dermatologist consultation to determine any changes that may potentially impact treatment decision-making, particularly when considering the dynamic nature of most immunosuppressive regimens.

In the treatment domain of an ICP’s journey, specific focus should be on a comprehensive review of the patient’s existing systemic medications to identify opportunities to reduce the risk of AK and SCC development. For OTRs, this may include a dose reduction of immunosuppressive medicines or a switch to medications with a demonstrated lower risk of SCC [e.g., mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors such as sirolimus or everolimus] [29, 30]. However, it is worth noting that switching to mTOR inhibitors after transplantation can be challenging because of increased risk of acute rejection during the transitional period, delayed graft functionality, or wound-healing complications [31, 32]. These changes should be made in conjunction with the patient’s wider MDT. Additionally, more aggressive treatment approaches (e.g., field-directed therapies) are likely needed to manage the increased risk of SCC development in ICPs’ follow-ups [33].

After the initial treatment phase, the panel acknowledged that regular follow-ups for all ICPs are not feasible in practice. Therefore, factors such as the number of AK lesions and evidence of SCC can guide which patients to monitor more closely. For OTRs, it is also important to assess the patient promptly after the end of the therapeutic course to determine efficacy and whether there is a need for further sequential treatment. Understanding the heightened risk of AK lesion progression to SCC in ICPs, the panel highlight the need for an “open door” policy that allows dermatologists to rapidly assess and treat developing lesions as soon as patients notice them. Subsequent monitoring and surveillance schedules should be tailored to each patient’s individual characteristics and needs [28, 34]. Additionally, monitoring (e.g., posttreatment local skin response) and clinical assessments (e.g., biopsies) should be frequent and thorough for all ICPs compared with non-ICPs. The panel recommended the Skin and Ultraviolet Neoplasia Transplant Risk Assessment Calculator (SUNTRAC) as a dynamic tool that may be used to better stratify OTRs into distinct cancer risk groups and identify high-risk patients, leading to more effective and efficient preventive measures [35, 36].

For the ongoing management of ICPs, the panel acknowledged that there is a greater need for patient education on the benefits of sun protection, diligent sun-avoidance measures, and self-examination to mitigate against the higher risk of SCC development [37]. Patient-friendly materials such as leaflets and video guides could enhance educational delivery by emphasizing the chronicity of AK, the importance of sun protection, and the need for repeated treatment. Increased use of highly protective sun protection in combination with educational programs and behavioral changes may reduce the risk of KC development in high-risk patients [37]. Increasing the accessibility to prophylactic measures (e.g., providing free sun protection tailored for KC prevention) may support their uptake in the ICP population. Moreover, collaboration with the patient’s MDT to deliver information on prevention strategies and communicate the long-term need for dermatology consultations would be beneficial. The panel also recommended prescribing long-term systemic preventative agents, such as oral retinoids (e.g., acitretin 10–25 mg/day depending on patients’ tolerability), to support the prevention of new lesion development and relapse [38]. The use of AK therapies with limited evidence in different ICP subgroups (e.g., imiquimod) was advised against, while UVA-specific prevention strategies should be implemented for cytotoxic agents that increase photosensitivity [e.g., azathioprine (AZA)] [39]. For OTRs, treatment should be administered earlier in the treatment journey compared with non-ICPs as a secondary prevention measure to minimize the risk of further development of AK lesions and novel SCC. A study by Togsverd-Bo et al. in patients that have had a renal transplant showed that early prevention with cyclic methyl aminolevulinate + PDT (MAL-PDT) significantly reduced the number of AK lesions in treated skin compared with untreated skin (32 versus 76, P < 0.01) [40]. Additionally, the probability of AK-free skin was 22% higher for treated skin versus untreated skin at 6-year follow-up (72% versus 50%), which may reduce the likelihood and morbidity of field cancerization [40].

Personalized Follow-Up and Disease Surveillance: A Novel Triage Tool

Novel, practical tools are required to determine accurate triage surveillance schedules to help maximize efficient use of dermatologist time. During the hybrid meeting, the IM-PAKT panel contributed to the development of a novel tool designed to aid in establishing treatment follow-up and disease surveillance schedules for ICPs. These insights were incorporated into a Danish triage table originally utilized for OTR patients with non-melanoma skin cancer [41]. This novel triage tool presented in Table 1 can support the development of long-term treatment plans for ICPs with AK. The triage tool provided a systematic approach to tailor screening frequencies based on specific disease characteristics and their subsequent risk profile and was advised for use in both clinical practice by dermatologists and as an educational aid.

For very high-risk patients, characterized by the presence of several invasive SCC lesions, the triage tool suggested screening examinations every 1–3 months. Patients with a history of SCC, widespread AK, or extensive sun damage were considered high risk and screening was recommended every 3–6 months [41].

Patients with a history of former basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or AK, or individuals over 50 years old with Fitzpatrick skin phototype I–II, were considered medium risk [41]. The panel recommended that these patients have screening examinations once or twice a year [41].

For individuals with a low risk profile (patients under 50 years with no previous AK or cancerization field, and all patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototype III–IV with no AK or cancerization field), screening was recommended every 12–18 months [41].

The panel emphasized that, instead of low-risk patients growing frustrated with repeat follow-up appointments when there is no new disease progression, tailored educational resources on prevention strategies and self-examination techniques may be more beneficial for both the patients and dermatologists. Additionally, follow-up appointments could be delegated to trained nurses or assisted with new technological developments, facilitating long-term disease surveillance while allowing dermatologists more time for higher-risk patients. However, the panel acknowledged that differences and constraints within healthcare systems between countries can have a significant influence on the standard of care and appointment time that dermatologists provide to patients.

Panel Feedback on Typical Patient Scenarios

The panel’s expert opinion on the assessment and management of three typical ICP scenarios that dermatologists are likely to encounter during clinical practice are summarized below. Key risk factors and considerations identified by the panel that relate to domains of the PAKT patient journey for each patient scenario are highlighted in Tables 3, 5, and 7. These fictional clinical cases were created to gather insight into how the panel would manage a typical ICP presenting to their clinic with AK lesions. In all cases, first assessment by the dermatologist should occur within 2–3 months of referral and involve a comprehensive skin examination, discussion of treatment goals, and detailed explanation of patients’ conditions and their associated risk of malignancy. Patients should also be encouraged to self-monitor for changes and educated on reducing UV exposure through sun protection measures: a study by Ulrich et al. reported that patients prescribed daily, highly protective sun protection (n = 60) experienced no new cases of invasive SCC, compared with patients in the non-sun protection control group (n = 60) where eight new cases occurred (P < 0.01) [37].

Patient 1

Patient #1 is a 57-year-old female with chronic inflammatory bowel disease who has been on azathioprine (100–150 mg/day) for over 25 years. With considerable UV exposure, she has a history of skin cancers and AKs, primarily on her hands, face, and chest, which were previously treated with R0 excisions and diclofenac 2.5% with hyaluronic acid 1.5%, respectively. However, the patient is hesitant to use topical 5-FU because of potential side effects. The panel identified that this patient is at high risk of developing new KCs because of prior AK/BCC/SCC and long-term pharmacological immunosuppression [notably azathioprine (AZA)], as highlighted in Table 2. As a known mutagenic, AZA can cause irreversible damage in patients who are exposed to sunlight [42, 43].

The following treatment plan was recommended for this patient by the IM-PAKT panel: the patient should undergo curettage and ablative fractional laser of hyperkeratotic lesions prior to repeated, short-interval cycles of MAL-PDT. Surgical intervention may be advisable for lesions showing signs of progression to SCC. Following these treatments, all remaining skin lesions should be inspected, with particular attention to freezing or excising any high-risk lesions. Lesions on the trunk/extremities should undergo treatment with ablative lasers or a 5-FU + salicylic acid cutaneous solution; it is important to clearly explain the benefits and side effects of 5-FU to reassure the patient that it is a viable option despite her reservations. The dermatologist should also collaborate with the patient’s gastroenterologist to transition the patient’s immunosuppressive treatment from AZA to a less mutagenic alternative, such as a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, vedolizumab, or ustekinumab.

The patient is likely to undergo cyclical treatments throughout the year, requiring monitoring every 3–6 months—even after clearance of AKs—to evaluate treatment response and disease severity. Depending on response and emergence of new lesions, the follow-up frequency can be reduced after 1 year but should continue for life. The panel note that acitretin in particular are recommended for long-term use. Additionally, field-directed therapy should be repeated until a significant reduction in persisting or new AKs in respective fields is achieved, and the panel recommend a lower threshold for conducting biopsies on suspicious or nonresponding lesions.

Patient 2

Patient #2 is a 71-year-old male with Fitzpatrick phototype IV, diagnosed with asymptomatic chronic lymphatic leukemia (CLL) over 10 years ago. The patient’s medical history includes Bowen’s disease and low-grade SCCs over several years, along with disseminated AKs in various areas. He has undergone excisions for keratoacanthomas and cryotherapy for individual AKs. The patient currently presents with multiple AK lesions and field cancerization, however, is currently on a watchful-waiting approach as he expresses concerns about undergoing painful treatments. This may increase the risk of the patient not diligently self-examining for any changes or informing the dermatologist of these changes, as emphasized in Table 3.

Patients with chronic lymphatic leukemia (CLL) and cutaneous SCCs are more likely to develop multiple tumors, recurrences after treatment, and regional/distant spread of tumors, which result in worse prognoses [44]. However, this patient is likely to have a lower risk of SCC progression than Patient 1, because of his darker skin type and long intervals between Bowen and SCC development.

There should be initial negotiations between the patient’s MDT to optimize the management of CLL and discuss potential AK treatment plans. The panel noted that the watchful waiting approach should be critically reviewed, and the risk of CLL-associated, multiple and aggressive KC development be flagged to the patient’s MDT.

The following treatment plan was recommended for this patient by the IM-PAKT panel: it is important to choose topical therapies that act independently from cellular immunity and show sustainable 12-month efficacy. Therefore, first-line treatment options that were suggested include topical tirbanibulin, or artificial/natural daylight therapy (A/DL-MAL PDT) which may also reduce therapeutic discomfort. Phototoxic and antiproliferative therapies may be beneficial as they are unlikely to cause an immune reaction in this patient. However, the panel noted that the use of topical immunomodulators may be less effective in treating SCC in patients with CLL, as observed during a retrospective study that reported a 25% objective response (complete and partial responses; n = 2/8) in patients with SCC and CLL compared with a ~50% response rate in clinical trials of patients with skin cancer without blood-related malignant comorbidities [45, 46]. For thicker lesions, second-line options may include a 5-FU + salicylic acid cutaneous solution or imiquimod, although it is crucial to educate the patient on how to treat local, potentially painful, cutaneous reactions. In case of a locally advanced or metastatic spread of cutaneous SCC, immune checkpoint inhibitors that provide promising treatment results in ICPs were noted by the panel to be less effective in patients with CLL [45, 46]. Shorter intervals between treatment were recommended for successful control, with repetitive cycles likely required to prevent further invasive KC development. There should be a follow-up examination after 4 months, followed by a consultation every 6 months if no new invasive lesions develop.

Patient 3

Patient #3 is a 45-year-old male farmer (Fitzpatrick phototype I) who had kidney failure and underwent dialysis followed by a kidney transplant in 2013. He has been experiencing recurrent AKs for the past 3 years and is on posttransplant immunosuppressive therapies (tacrolimus + mycophenolate mofetil + corticosteroids). His treatment history includes laser treatment, conventional PDT (discontinued because of skin complaints), and DL-PDT. Currently, he presents with multiple AK lesions and field cancerization, and is undergoing off-label treatment with ADL-PDT, which appears to be effectively controlling his condition. As highlighted in Table 4, AKs in OTR patients represent one of the greatest risk factors for developing SCCs [7, 8], warranting higher prioritization, quick assessment and treatment, and regular follow-ups for this patient. The dermatologist should ensure that biopsies are performed on all suspicious or nonresponding lesions. Moreover, the panel emphasize that the patient should consider retirement from farming, if he has not already done so posttransplant surgery.

The following treatment plan was recommended for this patient by the IM-PAKT panel. Firstly, there should be intense pretreatment with curettage or ablative fractional lasers, specifically for hyperkeratotic lesions. To reduce the likelihood of progression of AK to SCC, recommended first-line treatments for facial areas would be ADL-MAL PDT every 3 months for the large cancerization field, or topical tirbanibulin, 5-FU, or imiquimod, the latter of which is thought to be effective in the management of malignancies in OTRs [47]. For extra-facial areas, the panel suggested conventional PDT with local anesthesia at regular intervals or topical 5-FU. Regular clinical and self-inspection would also monitor potential SCC progression, with freezing or excision if required. Collaborating with the patient’s MDT to discuss the immunosuppressive regimen was advised as some drugs can have a greater carcinogenic effect, with the panel highlighting that mTOR inhibitors are preferable to tacrolimus or mycophenolates.

Following initial treatment, the patient should be advised to continue treatment at home with 5-FU or imiquimod. Preventive, twice annual, cyclic MAL-PDT sessions to assess treatment response and monitor disease severity were also recommended. If no new lesions emerge, 3-monthly examinations should be increased to yearly intervals, with patient-initiated follow-ups between scheduled visits. Oral acitretin may be considered as a chemopreventive measure [48]. Exploring preventive strategies would be essential, especially considering the importance of immunosuppression for graft maintenance.

Conclusions

The IM-PAKT panel have identified multiple areas of limitation in current management strategies for AK that have a profound impact on the standard of care received by ICPs. Guidance is currently lacking on treatment options that specifically address factors relevant to ICPs (e.g., posttransplant immunosuppressive regimens), patient and physician education, and risk stratification guidance for different ICP subgroups.

To tailor the PAKT clinical tool for ICPs, the IM-PAKT panel highlighted several recommendations to support better treatment outcomes and patient satisfaction. Establishing collaborative and transparent relationships with patients’ wider MDTs would help to promote optimal care for all comorbidities and alleviate some of the burden experienced by these patients. Additionally, ICPs with AK should be given access to earlier assessments and interventions than immunocompetent individuals because of their increased risk of progression to malignancy, and frequent reviews of an ICP’s existing medications should be conducted to identify opportunities to reduce the risk of AK and SCC development. Follow-ups and disease surveillance should be more thorough in these high-risk patients, and patient-initiated follow-ups between scheduled visits should be readily available.

As part of the IM-PAKT project, the panel presented a novel triage tool designed to support long-term and tailored approaches for treatment follow-up and disease surveillance for ICPs depending on their risk profile. The panel also provided their expert opinion on management suggestions for three theoretical ICP scenarios that dermatologists are likely to encounter in clinical practice. This allowed the panel to explain their decision-making processes to highlight how they believe that management plans should be adapted for ICPs compared with immunocompetent patients.

Overall, the gaps and limitations in AK care identified by IM-PAKT can help to guide further work and research in AK management for ICPs; in particular, the development of educational materials for both patients and physicians should be encouraged to highlight how AK management must be adapted in ICPs versus immunocompetent patients. Additionally, dermatologists should aim to promptly assess ICP cases by individual risk factors and clinical presentations to establish personalized management strategies, while ensuring clear and open communication with patients’ wider MDTs to coordinate treatments and stay informed about overall care plans.

References

Balcere A, Kupfere MR, Čēma I, Krūmiņa A. Prevalence, discontinuation rate, and risk factors for severe local site reactions with topical field treatment options for actinic keratosis of the face and scalp. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55:92.

Cerio R. The importance of patient-centred care to overcome barriers in the management of actinic keratosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:17–20.

de Berker D, McGregor JM, Mohd Mustapa MF, Exton LS, Hughes BR. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the care of patients with actinic keratosis. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:20–43.

Hasan ZU, Ahmed I, Matin RN, et al. Topical treatment of actinic keratoses in organ transplant recipients: A feasibility study for SPOT (Squamous cell carcinoma Prevention in Organ transplant recipients using Topical treatments). Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:324–37.

Ratushny V, Gober MD, Hick R, Ridky TW, Seykora JT. From keratinocyte to cancer: The pathogenesis and modelling of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:464–72.

Supapannachart KJ, Kwon CW, Tushe S, Guest JL, Chen SC, Yeung H. Validation of actinic keratosis diagnosis and treatment codes among veterans living with HIV. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2022;31:998–1002.

Togsverd-Bo K, Halldin C, Sandberg C, et al. Photodynamic therapy is more effective than imiquimod for actinic keratosis in organ transplant recipients: A randomized intraindividual controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:903–9.

Lindberg MR, Kent RA, DeSimone JA. Quarterly photodynamic therapy for prevention of nonmelanoma skin cancer in organ transplant recipients: an observational prospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:463–5.

Liew YCC, De Souza NNA, Sultana RG, Oh CC. Photodynamic therapy for the prevention and treatment of actinic keratosis/squamous cell carcinoma in solid organ transplant recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:251–9.

Eisen DB, Asgari MM, Bennett DD, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:e209–33.

Heppt MV, Leiter U, Steeb T, et al. S3 guidelines for actinic keratosis and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma – short version, part 1: Diagnosis, interventions for actinic keratoses, care structures and quality-of-care indicators. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:275–94.

Basset-Seguin N, Baumann Conzett K, Gerritsen MJP, et al. Photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis in organ transplant patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:57–66.

Tennvall GR, Norlin JM, Malmberg I, Erlendsson AM, Hædersdal M. Health related quality of life in patients with actinic keratosis—an observational study of patients treated in dermatology specialist care in Denmark. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:111.

Abbott P. Patient-centred health care for people with chronic skin conditions. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:329–30.

Eicher L, Knop M, Aszodi N, Senner S, French LE, Wollenberg A. A systematic review of factors influencing treatment adherence in chronic inflammatory skin disease – strategies for optimizing treatment outcome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:2253–63.

Morton C, Baharlou S, Basset-Sequin N, et al. Expert recommendations on facilitating personalized approaches to long-term management of actinic keratosis: The Personalizing Actinic Keratosis Treatment (PAKT) project. Acta Derm Venereol. 2023;103:adv6229.

Poulin Y, Lynde CW, Barber K, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer in Canada chapter 3: Management of actinic keratoses. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:227–38.

Werner RN, Jacobs A, Rosumeck S, Erdmann R, Sporbeck B, Nast A. Methods and results report—evidence and consensus-based (S3) guidelines for the treatment of actinic keratosis—International League of Dermatological Societies in cooperation with the European Dermatology Forum. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:e1–66.

Stratigos AJ, Garbe C, Dessinioti C, et al. European interdisciplinary guideline on invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: Part 2. Treatment Eur J Cancer. 2020;128:83–102.

Leiter U, Heppt MW, Steeb T, et al. German S3 guideline “actinic keratosis and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma” – long version of the update 2023. EJC Skin Cancer. 2023;1: 100004.

Foster AD, Sivarapatna A, Gress RE. The aging immune system and its relationship with cancer. Aging Health. 2011;7:707–18.

Fulop T, Larbi A, Dupuis G, et al. Immunosenescence and Inflamm-Aging As Two Sides of the Same Coin: Friends or Foes? Front Immunol. 2018;8:1960.

Khanna R, Bakshi A, Amir Y, Goldenberg G. Patient satisfaction and reported outcomes on the management of actinic keratosis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:179–84.

Jinna S, Khandhar PB. Hydroxyurea toxicity. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing 2024. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537209/. accessed 17 Mar 2024.

Russell MD, Stovin C, Alveyn E, et al. JAK inhibitors and the risk of malignancy: A meta-analysis across disease indications. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:1059–67.

Pellacani G, Schlesinger T, Bhatia N, et al. Efficacy and safety of tirbanibulin 1% ointment in actinic keratoses: Data from two phase-III trials and the real-life clinical practice presented at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress 2022. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:3–15.

Cohen JL. Actinic keratosis treatment as a key component of preventive strategies for nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:39–44.

Griffin L, O’Reilly P, Murphy M, et al. Photoprotection and skin cancer education: the experiences of renal transplant recipients, a qualitative study—why the ‘personal touch’ is important. Br J Dermatol. 2023;189:145–7.

De Fijter JW. Cancer and mTOR inhibitors in transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2017;101:45–55.

Kauffman HM, Cherikh WS, Cheng Y, Hanto DW, Kahan BD. Maintenance immunosuppression with target-of-rapamycin inhibitors is associated with a reduced incidence of de novo malignancies. Transplantation. 2005;80:883–9.

Tedesco-Silva H, Peddi VR, Sanchez-Fructuoso A, et al. Open-label, randomized study of transition from tacrolimus to sirolimus immunosuppression in renal allograft recipients. Transplant Direct. 2016;2: e69.

Flechner SM, Glyda M, Cockfield S, et al. The ORION study: comparison of two sirolimus-based regimens versus tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil in renal allograft recipients. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1633–44.

Huang A, Nguyen JK, Austin E, Mamalis A, Jagdeo J. Updated on treatment approaches for cutaneous field cancerization. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2019;8:122–32.

Acuna SA, Huang JW, Scott AL, et al. Cancer screening recommendations for solid organ transplant recipients: A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:103–14.

Gómez-Tomás Á, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Genders R, et al. External validation of the Skin and UV Neoplasia Transplant Risk Assessment Calculator (SUNTRAC) in a large European solid organ transplant recipient cohort. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:29–36.

Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Crow LD, Lowenstein S, et al. Predicting skin cancer in organ transplant recipients: development of the SUNTRAC screening tool using data from a multicenter cohort study. Transpl Int. 2019;32:1259–67.

Ulrich C, Jürgensen JS, Degen A, et al. Prevention of non-melanoma skin cancer in organ transplant patients by regular use of a sunscreen: a 24 months, prospective, case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:78–84.

Ramchatesingh B, Martínez Villarreal A, Arcuri D, et al. The use of retinoids for the prevention and treatment of skin cancers: An updated review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:12622.

Hofbauer GFL, Attard NR, Harwood CA, et al. Reversal of UVA skin photosensitivity and DNA damage in kidney transplant recipients by replacing azathioprine. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:218–25.

Togsverd-Bo K, Sandberg C, Helsing P, et al. Cyclic photodynamic therapy delays first onset of actinic keratoses in renal transplant recipients: A 5-year randomized controlled trial with 12-month follow-up. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:e946–8.

Danske Multidisciplinære Cancer Grupper. Non-melanom hudcancer hos organtransplanterede – screening, forebyggelse, behandling og opfølgning. 2022. Available at: https://www.dmcg.dk/Kliniske-retningslinjer/kliniske-retningslinjer-opdelt-paa-dmcg/non-melanom/non-melanom-hudcancer-hos-organtransplanterede--screening-forebyggelse-behandling-og-opfolgning/. Accessed 17 Jan 2024.

Ulrich C, Stockfleth E. Azathioprine, UV light, and skin cancer in organ transplant patients—do we have an answer? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1027–9.

O’Donovan P, Perrett CM, Zhang X, et al. Azathioprine and UVA light generate mutagenic oxidative DNA damage. Science. 2005;309:1871–4.

Velez NF, Karia PS, Vartanov AR, Davids MS, Brown JR, Schmults CD. Association of advanced leukemic stage and skin cancer tumor stage with poor skin cancer outcomes in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:280–7.

Jansen P, Lodde GC, Wetter A, et al. Checkpoint immunotherapy of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in patients suffering from chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: Divergent outcomes in two men treated with PD-1 inhibitors. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:41–4.

Leiter U, Loquai C, Reinhardt L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition therapy for advanced skin cancer in patients with concomitant hematological malignancy: a retrospective multicenter DeCOG study of 84 patients. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8: e000897.

Kovach BT, Stasko T. Use of topical immunomodulators in organ transplant recipients. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:19–27.

Harwood CA, Leedham-Green M, Leigh IM, Proby CM. Low-dose retinoids in the prevention of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas in organ transplant recipients: A 16-year retrospective study. Arch Dermatol. 2015;141:456–65.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Under the direction of the authors, medical writing support was provided by Shounak De, MPharm, and Charlotte Lewis, BSc, of Ogilvy Health UK, and funded by Galderma.

Funding

Authors were invited by Galderma who funded the planning and delivery of this project. Medical writing services, provided by Ogilvy Health UK, and the Rapid Service Fee were funded by Galderma.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rolf-Markus Szeimies, Claas Ulrich, Carla Ferrándiz-Pulido, Gunther Hofbauer, John Lear, Celeste Lebbé, Stefano Piaserico, and Mereta Hædersdal participated in the hybrid meeting and drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript. Special recognition is extended to Profs. Rolf Markus Szeimies and Claas Ulrich for their significant contributions to the development of the fictional case studies. Galderma provided a formal review of the publication (reviewed for accuracy), but the authors had final authority.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Rolf Markus Szeimies has received grants from Almirall, Biofrontera, Dr. Wolff-Group, Galderma, Leo Pharma, Novartis, and Photonamic for clinical studies, has received consulting fees and speaker honoraria from Abbvie, Almirall, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, and Leo Pharma, and is Vice-President of the EURO-PDT Society. Claas Ulrich has received study grants and/or has served as speaker and advisor for AlphaTau, Almirall, Beiersdorf, BMS, Galderma, GME, Hans Karrer AG, Novartis, Philogen, Pierre Fabre, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma. Carla Ferrándiz-Pulido declares to have participated in advisory boards and/or received honoraria from Almirall, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi, and Sun Pharma. Gunther Hofbauer has received research support from the Swiss National Fund, has acted as a speaker for AbbVie, Galderma Spirig, LEO Pharma, L’Oréal, Louis Widmer, MEDA, Merck, Novartis, Permamed, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi Genzyme, and acted as a consultant for AbbVie, Almirall, Biofrontera/Louis Widmer, Galderma Spirig, Hoffmann-La Roche, LEO Pharma, MEDA, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme. John Thomas Lear has acted as an advisor and received honoraria from Almirall, Galderma, and Leo Pharma. Celeste Lebbé has served as a consultant for Bristol Myers Squibb, Galderma, Immunocore, MSD, Novartis, and Pierre Fabre. Stefano Piaserico has no conflicts of interest relating to the publication of this manuscript. Merete Hædersdal has received research grants from or acted as a consultant for Galderma, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal/La Roche-Posay, Lutronic, Procter & Gamble, and Venus Concept, has acted as a lecturer for Galderma, and has received equipment from Cherry Imaging, Cynosure, GME Medical, Lutronic, MiraDry, and Venus Concept.

Ethical Approval

Information presented in this article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any data from new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Szeimies, RM., Ulrich, C., Ferrándiz-Pulido, C. et al. The “Personalising Actinic Keratosis Treatment for Immunocompromised Patients” (IM-PAKT) Project: An Expert Panel Opinion. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-024-01215-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-024-01215-y