Abstract

Introduction

Keloids are lesions characterized by the growth of dense fibrous tissue extending beyond original wound boundaries. Research into the natural history of keloids and potential differences by sociodemographic factors in the USA is limited. This real-world, retrospective cohort study aimed to characterize a population of patients with keloids compared with matched dermatology and general cohorts.

Methods

Patients with ≥ 2 International Classification of Diseases codes for keloid ≥ 30 days apart and a confirmed keloid diagnosis from clinical notes enrolled in the OM1 Real-World Data Cloud between 1 January 2013 and 18 March 2022 were age- and sex-matched 1:1:1 to patients without keloids who visited dermatologists (“dermatology cohort”) and those who did not (“general cohort”). Results are presented using descriptive statistics and analysis stratified by cohort, race, ethnicity, household income, and education.

Results

Overall, 24,453 patients with keloids were matched to 23,936 dermatology and 24,088 general patients. A numerically higher proportion of patients with keloids were Asian or Black. Among available data for patients with keloids, 67.7% had 1 keloid lesion, and 68.3% had keloids sized 0.5 to < 3 cm. Black patients tended to have larger keloids. Asian and Black patients more frequently had > 1 keloid than did white patients (30.6% vs. 32.5% vs. 20.5%). Among all patients with keloids who had available data, 56.4% had major keloid severity, with major severity more frequent in Black patients. Progression was not significantly associated with race, ethnicity, income, or education level; 29%, 25%, and 20% of the dermatology, keloid, and general cohorts were in the highest income bracket (≥ US$75,000). The proportion of patients with income below the federal poverty line (< US$22,000) and patterns of education level were similar across cohorts.

Conclusion

A large population of patients in the USA with keloids was identified and characterized using structured/unstructured sources. A numerically higher proportion of patients with keloids were non-white; Black patients had larger, more severe keloids at diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Research into the natural history of keloids and potential differences by sociodemographic factors in the USA is limited. |

This real-world, retrospective cohort study aimed to use structured and unstructured secondary data sources of a large US-based cohort to characterize a population of patients with keloids and matched dermatology and general cohorts, including descriptions of the severity and progression, with an emphasis on understanding any differences by sociodemographic factors. |

What was learned from the study? |

A large population of patients in the USA with keloids was identified and characterized using structured/unstructured sources, and a numerically higher proportion of patients with keloids were non-white. |

Within the keloid cohort, the most common comorbidities were hypertension, acne, depression, and anxiety; Black patients had larger and more severe keloids at diagnosis than other racial groups. Keloid progression was not linked to race, ethnicity, or household income level. This information provided in this study may guide research toward new effective or curative treatments, which remain an unmet medical need. |

Introduction

Keloids are lesions characterized by the growth of dense fibrous tissue extending beyond the boundaries of the original wound [1, 2]. These lesions may manifest on the skin of any body part but most commonly affect the shoulders, chest, upper back, and ears [3]. Keloids are often raised and firm and can frequently cause pain or pruritus [2]. Compared with hypertrophic scars, which are usually confined to the borders of the initial injury and flatten with time, keloids rarely spontaneously regress [3, 4]. While some keloids remain stable over time, severe keloids can continue to grow and spread, extending several centimeters [5].

Keloids can affect people of all races; however, prior studies have indicated that keloids disproportionately occur in certain subgroups of patients. There is limited evidence that younger patients are more susceptible to keloid formation. One study of 1000 patients in South India found that patients aged 10–30 years were most often affected [6], while another study of 120 patients in Nigeria found that young adults were primarily affected [7]. Darker skin pigmentation may also carry greater risk for keloids [8]. The prevalence of keloids reported in various studies has varied widely by country, with estimates of 0.09% in England [9], 8.5% in Kenya [10], 0.1% in Japan [11], and 16% in Zaire [12]. One study of 402 patients living in Ghana, Australia, Canada, and England found that the prevalence of keloids was higher in the Ghanaian population [13], while another study evaluating 175 patients of Chinese, Malaysian, or Indian descent found a higher rate of keloids in patients of Chinese descent [14]. A UK-based study examining the prevalence of excessive scarring in a heterogeneous cohort of 972 patients found the prevalence to be 1.1%, 2.4%, and 0.4% for Asian, Black, and white patients, respectively [15]. Within the same study, female sex, hypertension, and atopic eczema were associated with scarring compared with 229 control patients; however, no distinction between keloids or hypertrophic scars was made in the study [15]. Socioeconomic status may also affect keloid formation. In a study of 89 Chinese patients, low or middle family income was associated with the formation of severe keloids (odds ratio [OR] 13.44; P = 0.005) [5].

While many prior studies have evaluated keloids in a real-world context, most of these studies have been small, conducted among patients in populations with less diversity, or focused on treatment options [16]. The objective of this analysis was to use structured and unstructured secondary data of a large US-based cohort to characterize a population of patients with keloids, including descriptions of the severity and progression of these lesions, with an emphasis on understanding any differences by sociodemographic factors.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

This was a retrospective, longitudinal cohort study of patients diagnosed with keloids in the USA. Results were derived using data within the Real-World Data Cloud (RWDC; OM1 Inc, Boston, MA, USA) from 1 January 2013 to 18 March 2022. The RWDC is a multisource data set derived from deterministically linked, deidentified, individual-level healthcare claims; electronic medical records (EMRs), including dermatology and otolaryngology specialty EMRs; and an insurance underwriting real-world data source with broad coverage of the US population. As keloids and hypertrophic scars are classified using the same International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, unstructured data sourced from EMRs were used to distinguish keloid from hypertrophic scar diagnoses. Unstructured EMR data were also used to identify the location, type, severity, and progression of keloids.

The study was conducted in accordance with legal and regulatory requirements, as well as with scientific purpose, value, and rigor and follows generally accepted research practices described in Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices issued by the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology, the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research guidance, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. All database records were deidentified in compliance with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA); therefore, informed consent from patients was not needed or obtained, and approval from an institutional review board was not required.

Patient Population

To meet inclusion criteria in the keloid group, patients had to have ≥ 2 ICD diagnosis codes for keloid or hypertrophic scar ≥ 30 days apart (ICD-9 code 701.4; ICD-10 code L91.0) and confirmed diagnosis of keloid scarring from unstructured data. Patients with hypertrophic scars were excluded from the keloid cohort. The index date was either the date of keloid diagnosis as reported in the clinical notes or the date of the first relevant ICD code in the structured data, whichever was earlier. Additional inclusion criteria for individual study objectives included ≥ 12 months of baseline data prior to the index date, based on evidence of an encounter in EMR or claims data; new diagnosis of keloids as defined by ≥ 12 months of data available prior to the index date and no prior diagnosis codes or diagnosis of keloids in the clinical notes; severity data within 90 days on or after index date available from unstructured data; and progression data available from unstructured data.

The population seeking medical care for keloids may differ from the overall population with keloids. To characterize the extent of potential selection bias, each keloid cohort patient was age- and sex-matched to one patient from a “dermatology comparator” cohort and one patient from a “general comparator” cohort. Inclusion criteria for the dermatology comparator cohort included an encounter with a dermatologist during the study period and an encounter date within 30 days of a matched keloid cohort patient’s index date. Exclusion criteria for the dermatology comparator cohort included a diagnosis code (ICD-9 701.4; ICD-10 L91.0) of keloid/hypertrophic scarring in the structured data recorded during the study period. Inclusion criteria for the general comparator cohort included an EMR encounter during the study period and an encounter date within 30 days of a matched keloid cohort patient’s index date. Exclusion criteria for the general comparator cohort included a diagnosis code (ICD-9 code 701.4; ICD-10 code L91.0) of keloid/hypertrophic scarring in the structured data recorded during the study period or an encounter with a dermatologist.

Study Variables and Outcomes

Structured data recorded at the index date included age, age category, sex, race, ethnicity, geographic region of the USA, insurance type, household income, highest education level achieved, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score and category. For patients with race and ethnicity recorded, the OM1 RWDC implements definitions for those terms consistent with those used by the US Census. The term “Asian” was used to describe a person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent including, for example, India, China, the Philippine Islands, Japan, Korea, or Vietnam. It includes people who indicate their race as “Asian Indian,” “Chinese,” “Filipino,” “Korean,” “Japanese,” “Vietnamese,” and “Other Asian” or provide other detailed responses such as Pakistani, Cambodian, Hmong, Thai, Bengali, Mien, etc. [17]. The term “Black” was used to describe a person having origins in any of the Black racial groups of Africa, including people who indicate their race as “Black or African American,” or report responses such as African American, Jamaican, Haitian, Nigerian, Ethiopian, or Somali. The category also includes groups such as Ghanaian, South African, Barbadian, Kenyan, Liberian, and Bahamian, among others [17].

Comorbidities or surgical procedures were reported if present prior to the index date, with either two ICD diagnosis codes ≥ 30 days apart (for comorbidities) or ≥ 1 procedure code (for surgical procedures). Unstructured data variables included index date; confirmed diagnosis of keloid; newly diagnosed or recurrent scar (identified within 90 days of index date); keloid severity (identified within 90 days of index date); number per patient, size, location, and type; and keloid progression ≤ 24 months post diagnosis. Keloid severity was categorized as major (defined as either physician assessment of moderate, severe, or major in the clinical notes or ≥ 1 of the following: size ≥ 0.5 cm; symptomatic; widespread; cosmetically sensitive location; or treatment with triamcinolone acetonide ≥ 20 mg within 90 days of the index date), minor (defined as either physician assessment of mild or asymptomatic in the clinical notes or ≥ 1 of the following: size < 0.5 cm; no symptoms; noncosmetically sensitive area; or minimally raised/flat within 90 days of the index date), or unknown. Keloid progression was assessed within 24 months post diagnosis and categorized as improved (described as improving; softer; becoming smaller; responding positively to treatment; improvement in symptoms [i.e., pain, itch, tenderness, unspecified]; vanishing; or regressing/regression), stable/no change (described as stable; not changing; same; or not improving), worsening (defined as not responding to treatment; becoming worse/worsening; larger; higher; wider; painful; tender; erosions; infection; or marked post-treatment hypopigmentation), or unknown.

Statistical Analysis

For identification of patients with confirmed keloid diagnoses, structured query language searches for term combinations including the word “keloid” were conducted [18]. Clinical notes containing the word “keloid” were reviewed by two researchers—a physician and an epidemiologist for surrounding language confirming the diagnosis, with guidance by a dermatologist. All other variables sourced from unstructured data were extracted from keloid cohort clinical notes through technology-assisted abstraction. Terms of interest were automatically highlighted and reviewed by a trained medical abstractor.

Given the lack of prior published evidence to support specific hypotheses, this was a descriptive, exploratory study intended to be hypothesis generating. As such, analyses primarily used descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were summarized by mean (standard deviation [SD]), and categorical variables were summarized by count and percentage. ORs and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values from ordinal logistic regression models were used to describe the progression of disease. Data analysis was performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), v9.4. A post hoc sensitivity analysis was conducted on baseline clinical characteristics, limited to patients with linked claims data.

The associations between risk factors and progression of keloids were examined using an ordinal logistic regression model that included progression (categorical variable: improving, stable, worsening) of keloids within 24 months of diagnosis as the dependent variable. Risk factors included in the model were selected based on clinical relevance as well as univariate analyses of the candidate variable. Risk factors included in the model a priori included race, ethnicity, household income level, and type of initial treatment. Interactions between initial treatment and other risk factors were also considered, as well as other variables hypothesized to be associated with progression (keloid severity, location, size, type, and number of keloids). The unit of analysis for this model was the patient.

Results

Patients and Baseline Demographics

The RWDC contained data on 305,713,424 patients, with demographic characteristics generally similar to those of the US population [19] by sex and geographic region (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] Table S1). A total of 24,453 patients with keloids met the main inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The dermatology comparator and general comparator cohorts consisted of 23,936 and 24,088 age- and sex-matched patients, respectively.

Cohort selection. aClinical notes in the RWDC are sourced from the DataDerm registry, the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery RegENT registry, and other general and specialty EMR sources. bThe index date is the first date a keloid was mentioned in the note or date of first ICD code; the definition of newly diagnosed patients is equivalent to having ≥ 12 months of data. Thus, the starting population for all objectives is the same. EMR Electronic medical record, ENT, Ear, nose, and throat, ICD International Classification of Diseases, RWDC Real-World Data Cloud

Patient demographics for the three cohorts are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 42.5–42.6 years, and 65.9–66.4% were female. Race varied across cohorts: in the keloid cohort, 4.9%, 18.8%, and 52.1% of patients were Asian, Black, and white, respectively, whereas these proportions were 1.9%, 4.5%, and 74.7% in the dermatology cohort and 1.8%, 8.8%, and 61.2% in the general cohort. Overall, Hispanic/Latino patients comprised 5.4%, 3.4%, and 7.4% of the keloid, dermatology comparator, and general comparator cohorts, respectively.

Information on household income was available for 11,554 adult patients across all cohorts; 25.1% of patients in the keloid cohort, 29.0% in the dermatology cohort, and 20.2% in the general cohort had household income ≥ US$75,000. The proportion of patients with income below the federal poverty level (US$22,000) was 1.4%, 1.0%, and 1.4% in the keloid, dermatology, and general cohorts, respectively.

Data on maximum education level achieved were available for 11,325 adult patients across all cohorts. Within the keloid cohort, the most common education levels attained were bachelor’s degree (21.6%) and high school graduate (15.6%). Similar patterns in education levels were seen for the dermatology and general comparator cohorts. Within the keloid cohort, 38.6% of patients had commercial insurance, 7.6% had Medicare, and 2.6% had Medicaid. Within the dermatology comparator cohort, 36.3% had commercial insurance, 7.0% had Medicare, and 1.3% had Medicaid. Within the general comparator cohort, 27.9% of patients had commercial insurance, 11.0% had Medicare, and 5.2% had Medicaid. The proportion of patients from each US region was comparable across cohorts.

Baseline Demographics Stratified by Race, Ethnicity, Household Income, and Education Level

In an assessment of baseline demographics of the keloid cohort stratified by race, white patients with keloids tended to be older and more frequently had Medicare insurance compared with Asian, Black, and multiple races/other patients with keloids (ESM Table S2). Overall, 0.3% of Asian patients, 2.5% of Black patients, 1.5% of white patients, and 0.8% of multiple races/other patients with keloids had incomes of < US$22,000; 26.2% of Asian patients, 16.2% of Black patients, 29.4% of white patients, and 21.8% of multiple races/other patients with keloids had household incomes of ≥ US$75,000. When stratified by ethnicity, Hispanic/Latino patients in the keloid cohort tended to be younger and more often had commercial insurance than non-Hispanic/Latino patients in the keloid cohort (mean age, 34.5 vs. 44.0 years; commercial insurance, 42.4% vs. 37.5%; EMS Table S3).

Among patients with keloids with a college degree, 3.9% were Asian, 14.2% were Black, and 62.1% were white; among those with a graduate degree, 3.5% were Asian, 12.4% were Black, and 66.0% were white (ESM Table S4). The majority of patients with a college or graduate degree were in the highest household income bracket (65.8% and 62.3%, respectively), compared with 34.7% of patients with a high school diploma.

When patients with keloids were stratified by household income, patient age tended to decrease with increasing household income (ESM Table S5); 72.9% of those with household income of < US$22,000 were aged ≥ 65 years. Black patients in the keloid cohort comprised 32.5% of the lowest income bracket and 12.2% of the highest income bracket. Nearly one-third of patients with household income < US$22,000 had Medicare insurance, compared with 18.7%, 8.8%, and 4.8% of those in the other income brackets.

The dermatology and general comparator cohorts followed similar patterns when stratified by race, ethnicity, highest education level achieved, and household income (ESM Tables S6-S13). In the dermatology comparator cohort, the distribution of race was more consistent across household income levels (ESM Table S8). In the general comparator cohort, there was less variation in mean age across race (ESM Table S10).

Clinical Characteristics

The mean (SD) CCI was 0.7 (1.4) for the keloid cohort, 0.5 (1.2) for the dermatology comparator cohort, and 1.0 (1.7) for the general comparator cohort (Table 2). The most common comorbidities within the keloid cohort were hypertension (9.4%), acne (8.0%), anxiety (3.3%), and depression (3.4%). Overall, general medical comorbidities such as hypertension and depression were more frequent in the general comparator cohort, while dermatologic comorbidities such as atopic dermatitis and acne were more frequent in the keloid and dermatology comparator cohorts.

A post hoc sensitivity analysis was conducted on patients who had claims data in addition to electronic health record data (ESM Table S14). The proportions of patients with hypertension, depression, and anxiety were numerically greater in all three cohorts among those with claims data versus those without.

Clinical Characteristics Stratified by Race, Ethnicity, Household Income, and Education Level

Black patients with keloids had hypertension more frequently than other racial groups (13.4% vs. 7.5% [Asian], 9.0% [white], and 9.9% [multiple races/other]) (ESM Table S15). In Hispanic/Latino patients compared with non-Hispanic/Latino patients in the keloid cohort, hypertension was less frequent (6.4% vs. 10.2%) and acne more frequent (11.4% vs. 8.0%; ESM Table S16). Comorbidities were consistent across patients with keloids when stratified by highest education level (ESM Table S17). Within the keloid cohort, the CCI score decreased with increasing household income bracket (1.5 vs. 1.1 vs. 0.8 vs. 0.6, respectively; ESM Table S18).

Generally, clinical characteristics within the dermatology and general comparator cohorts were comparable to those of the keloid cohort when stratified by ethnicity, education level, and household income (ESM Tables S19-S26). Hypertension was more prevalent among all races in the general comparator cohort compared with the keloid cohort (25.9% [Asian], 30.5% [Black], 18.7% [white], and 24.1% [multiple races/other]; ESM Tables S15, S23).

Keloid Characteristics

Among 7893 patients with data on number of keloids available, the most common numbers of keloids documented were 1 keloid (67.7%; Table 3) and > 1 keloid without the exact number reported (25.7%). Within the keloid cohort, size was documented for 622 lesions; the most common size was 0.5 to < 3 cm (68.3% of cohort). Anatomical location was available for 8627 lesions; among these lesions, the most common locations were the chest (25.7%), ear (24.4%), and back (10.9%). Keloid type in the 90 days after diagnosis was documented for 272 patients; among lesions with these data, 52.2% were primary and 47.8% were recurrent keloids. Keloid severity was major in 56.4% of patients and minor in 43.6%.

Keloid Characteristics Stratified by Race, Ethnicity, Household Income, and Education Level

Within the keloid cohort, a numerically higher proportion of white patients had only 1 keloid (74.0% vs. 62.0% [Asian], 59.6% [Black], and 65.1% [multiple races/other]; Fig. 2; Table 3). A numerically higher proportion of Black and multiple races/other patients had keloids with a size ranging from 3 to < 11 cm (35.3% [multiple races/other] vs. 31.3% [Black], 17.6% [Asian], and 15.3% [white]). Among patients with keloid location documented, the most common locations varied by race. Among Asian patients, the most common keloid locations were the chest (35.0%), ear (14.6%), and shoulder/deltoid (12.1%). For Black patients, the most common keloid locations were the ear (33.1%), chest (20.8%), and abdomen (8.3%). For white patients, the most frequent locations were the chest (27.5%), ear (19.6%), and back (14.1%). For multiple races/other patients, the most frequent locations were the chest (25.5%), ear (25.0%), and shoulder/deltoid (13.7%). A numerically higher proportion of Black patients had major keloids at diagnosis (62.5% vs. 54.2% [Asian], 53.2% [white], and 52.7% [multiple races/other]). When stratified by ethnicity, maximum education achieved, and household income, keloid characteristics followed similar distributions seen in the overall keloid cohort (ESM Tables S27-S29).

Keloid characteristics, stratified by race. a Number of keloids, b size of keloids, c keloid type, d keloid severity at diagnosis, e progression of keloids within 24 months post diagnosis. Note: Keloid severity (d) was categorized as major (defined as either physician assessment of moderate, severe, or major in the clinical notes or ≥ 1 of the following: size ≥ 0.5 cm, symptomatic, widespread, cosmetically sensitive location, or treatment with triamcinolone acetonide dosage ≥ 20 mg within 90 days of the index date), minor (defined as either physician assessment of mild or asymptomatic in the clinical notes or ≥ 1 of the following: size < 0.5 cm, no symptoms, noncosmetically sensitive area, or minimally raised/flat within 90 days of the index date), or unknown. Note: Keloid progression (e) was assessed within 24 months post diagnosis and categorized as improved (described as improving, softer, becoming smaller, responding positively to treatment, improvement in symptoms, vanishing, regressing, or regression), stable/no change (described as stable, not changing, same, or not improving), worsening (defined as not responding to treatment, becoming worse/worsening, larger, higher, wider, painful, tender, erosions, infection, or marked post-treatment hypopigmentation), or unknown

Keloid Progression

Data on keloid progression within 24 months of diagnosis were available for 2828 patients (Table 3). Among patients with progression reported, 69.7% indicated improvement, 18.4% indicated worsening, and 4.8% indicated stable keloids or no change. For 7.1% of patients, progression was mixed, meaning that some aspects of the keloid improved, while others worsened or were stable, or the patient had multiple lesions with variable outcomes.

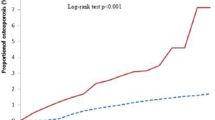

An ordinal logistic regression model was used to estimate the odds of keloid worsening compared with improving or remaining stable. Race, ethnicity, household income level, and initial treatment type were prespecified as risk factors of interest in the model. Race, ethnicity, and household income level were not significantly associated with keloid progression (Fig. 3). Compared with patients who received only medications as their initial treatment, patients who received only procedures (OR 2.1; 95% CI 1.5–3.1; P < 0.001), procedures and medications (OR 1.5; 95% CI 1.0–2.1; P = 0.03), or unknown/not reported (OR 1.8; 95% CI 1.5–2.2; P < 0.001) as their initial treatment had higher odds of worsening keloids. Other variables hypothesized to be associated with keloid progression, such as severity, location, and size, were also assessed for inclusion but were not included in the final model due to high rates of missing data.

Association between risk factors and worseninga of keloids. aKeloid progression was assessed within 24 months post diagnosis and categorized as improved (described as improving, softer, becoming smaller, responding positively to treatment, improvement in symptoms, vanishing, regressing, or regression), stable/no change (described as stable, not changing, same, or not improving), worsening (defined as not responding to treatment, becoming worse/worsening, larger, higher, wider, painful, tender, erosions, infection, or marked post-treatment hypopigmentation), or unknown. bReference: white race (n = 1170). cReference: not Hispanic/Latino (n = 1712). dReference: ≥ US$75,000 (n = 614). eReference: only medications (n = 1027)

Discussion

In this retrospective, longitudinal cohort study of patients with keloids in the USA, a majority of the patients in the keloid cohort were female, and a numerically higher proportion of patients with keloids were non-white compared with two matched comparator cohorts of patients without keloids. The most common comorbidities for the keloid cohort were hypertension, acne, depression, and anxiety. Within the keloid cohort, Black patients tended to have larger and more severe keloids at diagnosis compared with patients of other races.

Prior literature has indicated that women may be at greater risk of keloid formation. The formation of multiple keloid lesions was found to be significantly more common in women in a study of 211 Jamaican patients [20]. A case series of 1659 Japanese patients with keloids who visited a plastic surgery clinic found that 57.6% of patients were female [21]. In a UK cohort, female sex was associated with excessive scarring [15]. In the present study, the majority of patients were female. However, it is unknown whether women are more likely to develop keloids or are more likely to solicit care, due to sociological differences.

One Japanese study reported an average of 10 years between keloid onset and first medical examination for keloids, and the mean age for first medical examination of keloids was 35 years [21]. In the present study, the average age of a patient at index diagnosis within the keloid cohort was 42.5 years; however, the mean age of patients within the keloid cohort varied by race, indicating that there may be underlying differences in keloid onset or timing of first medical examination among races.

Several comorbidities were found to occur frequently in the keloid population in the current study, including hypertension, acne, depression, and anxiety. Hypertension may be a risk factor for pathological scarring [22]. One prior study examining comorbidities in 972 UK patients with keloids or hypertrophic scars compared with a matched healthy cohort found that excessive scarring was associated with hypertension in Black patients [15]. Another study from a US regional hospital found that 7.9% of 129 Black patients aged < 30 years with keloids had hypertension, compared with 0% of 65 Black patients aged < 30 years without keloids [23]. The current study found that rates of hypertension in patients with keloids varied by race, from 7.5% of Asian patients to 13.4% of Black patients. By comparison, within the matched dermatology cohort, the rates of hypertension were 1.6% of Asian patients and 8.4% of Black patients, and within the general cohort, the rates were 17.4% of Asian patients and 30.5% of Black patients. Additionally, hypertension and acne share similar pathological inflammatory pathways as keloid scarring, which may indicate a link between the comorbidities. Keloid scarring has been linked to the T helper 2 (Th2), JAK/STAT, and interleukin (IL)-17/IL-6 signaling axes, with keloid lesions displaying increased levels of IL-6 and tumor growth factor beta (TGF-β) [24, 25]. Acne vulgaris pathogenesis is linked to IL-6- and TGF-β-induced activation of T helper 17 (Th17) cells [26]; IL-6 also has shown positive correlation with acne disease severity [27]. Hypertension can lead to activation of a TGF-β signaling cascade, resulting in fibrosis [22]; such fibrosis may also affect wound healing. By comparison, an increased risk of depression and anxiety may stem from the physical disfigurement of scars or the continued growth of some keloids.

In one Chinese cohort of patients with keloids, 35.5% had severe keloids, defined as ≥ 10 keloids or size ≥ 40 cm2 [5]. In the current study, broader definitions were used, including descriptions from unstructured clinical notes, resulting in a greater prevalence; however, severity was often not recorded in clinical notes, which complicates attempts to study keloid outcomes.

Lower socioeconomic status (such as income and education level) has been linked to worse health outcomes and disease severity across many immune-mediated diseases, including multiple sclerosis [28, 29], rheumatoid arthritis [30, 31], systemic lupus erythematosus [32], and asthma [33]. In the current study, lower household income correlated with both increased patient age and higher CCI score. Within this population of patients who received dermatologist care for keloids, keloid characteristics and progression followed similar patterns when stratified by education level and household income as in the overall keloid cohort.

An ordinal logistic regression model showed that patients who only received medications as initial treatment were less likely to have keloid worsening than patients who had only procedures (such as surgical excision) or procedures and medications as initial treatment; however, race, ethnicity, and income level were not significantly associated with keloid worsening. Two prior Chinese studies on risk factors of progression to severe keloids found that hypertension, infection, low or middle family income, rheumatism, multiple keloids at multiple sites, and disease duration were significantly associated with progression from mild to severe keloids, while skin color was not associated with more severe keloids [5, 34]. Keloid formation was not examined. Our data indicated that race and ethnicity were not associated with keloid worsening.

While progression data were only available for a small subset of patients in the current study, future research could examine the impact of recurrence after treatment on reported progression. This is especially important, as there are no approved treatments for keloids at the present time. Therapy with procedures such as lasers have previously been associated with keloid worsening compared with medication only [35]. One Korean hospital examined risk factors for keloid recurrence in 203 pediatric patients [36]. Lower body or chest location and certain treatment combinations (surgical excision, skin grating, and steroid injection or surgical excision and steroid injection) were associated with keloid worsening [36]. Another Korean hospital study of recurrence of earlobe keloids in pediatric patients treated with surgical excision found no benefit of adjuvant injectable corticosteroid therapy and found no difference in recurrence with regard to race or keloid size [37].

This study included some limitations. First, as confirmed diagnoses of keloid lesions originated primarily as clinical notes from dermatologist and otolaryngologist encounters, there is the potential for patients to be misclassified with respect to keloid diagnosis in the absence of gold standard diagnosis confirmation based on lesion images. Second, due to different source databases from which the keloid, dermatology, and general cohorts were derived, differences in baseline comorbidities may not accurately represent the true extent of comorbidities among the cohorts. Third, due to differences in note-taking practices and a lack of established gold standard guidelines, outcomes data (such as keloid size, type, progression, severity at diagnosis, etc.) were not consistently available for all patients at all visits. Due to the missingness of outcomes data, the association between keloid severity and progression could not be assessed. Patient characteristics associated with unequal access to certain types of specialty healthcare providers may also be linked to the quality or accuracy of information captured in clinical notes. Finally, it is important to note that because this study was conducted as an exploratory, hypothesis-generating study, statistical testing of the differences between cohorts with regard to patient characteristics and comorbidities was not done, and results should be interpreted accordingly.

Regardless of these limitations, this study leveraged available clinical notes from a database broadly representative of the US population to identify a large population of patients with keloids, which could not be identified using typical diagnosis code–based methods. Additionally using clinical notes, information concerning keloid location, number, size, severity, and progression was obtained, which has not been previously reported in a cohort this large.

Conclusions

In this retrospective, longitudinal cohort study of US patients with keloids, a numerically higher proportion of patients with keloids were non-white compared with a dermatology patient cohort and a general patient cohort. The most common comorbidities for the keloid cohort were hypertension, acne, depression, and anxiety. Within the keloid cohort, Black patients tended to have larger and more severe keloids at diagnosis compared with patients of other races. Keloid progression was not linked to race, ethnicity, or household income level. These results may inform greater understanding of the burden of disease, and this burden may vary across patient demographic characteristics. Future research is needed to investigate keloid severity and progression in a larger cohort of patients.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the confidential and proprietary nature of the data sets.

References

Lee HJ, Jang YJ. Recent understandings of biology, prophylaxis and treatment strategies for hypertrophic scars and keloids. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(3):711.

Betarbet U, Blalock TW. Keloids: a review of etiology, prevention, and treatment. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(2):33–43.

Chike-Obi CJ, Cole PD, Brissett AE. Keloids: pathogenesis, clinical features, and management. Semin Plast Surg. 2009;23(3):178–84.

Ghazawi FM, Zargham R, Gilardino MS, Sasseville D, Jafarian F. Insights into the pathophysiology of hypertrophic scars and keloids: how do they differ? Adv Skin Wound Care. 2018;31(1):582–95.

Liu R, Xiao H, Wang R, Li W, Deng K, Cen Y, et al. Risk factors associated with the progression from keloids to severe keloids. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022;135(7):828–36.

Halim AS, Emami A, Salahshourifar I, Kannan TP. Keloid scarring: understanding the genetic basis, advances, and prospects. Arch Plast Surg. 2012;39(3):184–9.

Alo AG, Akinboro AO, Ajani AA, Olanrewaju FO, Oripelaye MM, Olasode OA. Keloids in darkly pigmented skin: clinical pattern and presentation at a tertiary health facility, southwest Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2022;39(8):829–35.

Bakhtyar N, Amini-Nik S, Jeschke MG. OMICS approaches evaluating keloid and hypertrophic scars. Int J Inflam. 2022;2022:1490492.

Kelly AP. Keloids. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6(3):413–24.

Kiprono SK, Chaula BM, Masenga JE, Muchunu JW, Mavura DR, Moehrle M. Epidemiology of keloids in normally pigmented Africans and African people with albinism: population-based cross-sectional survey. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(3):852–4.

Téot L, Mustoe TA, Middelkoop E, Gauglitz GG. Textbook on scar management: state of the art management and emerging technologies. New York: Springer; 2020.

Louw L. Keloids in rural black South Africans. Part 1: general overview and essential fatty acid hypotheses for keloid formation and prevention. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2000;63(5):237–45.

Stanley GHM, Pitt ER, Lim D, et al. Prevalence exposure and the public knowledge of keloids on four continents. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2023;77:359–70.

Alhady SM, Sivanantharajah K. Keloids in various races. A review of 175 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;44(6):564–6.

Ung CY, Warwick A, Onoufriadis A, et al. Comorbidities of keloid and hypertrophic scars among participants in UK Biobank. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159(2):172–81.

Aggarwal A, Ravikumar BC, Vinay KN, Raghukumar S, Yashovardhana DP. A comparative study of various modalities in the treatment of keloids. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(10):1192–200.

US Census Bureau. Race. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/note/US/RHI625222. Accessed 2 Oct 2023.

Bustamante R, Earles A, Murphy JD, et al. Ascertainment of aspirin exposure using structured and unstructured large-scale electronic health record data. Med Care. 2019;57(10):e60–4.

US Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States (v2021). 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221. Accessed 2 May 2023.

Bayat A, Arscott G, Ollier WE, McGrouther DA, Ferguson MW. Keloid disease: clinical relevance of single versus multiple site scars. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58(1):28–37.

Noishiki C, Hayasaka Y, Ogawa R. Sex differences in keloidogenesis: an analysis of 1659 keloid patients in Japan. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019;9(4):747–54.

Huang C, Ogawa R. The link between hypertension and pathological scarring: does hypertension cause or promote keloid and hypertrophic scar pathogenesis? Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22(4):462–6.

Woolery-Lloyd H, Berman B. A controlled cohort study examining the onset of hypertension in black patients with keloids. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12(6):581–2.

Wu J, Del Duca E, Espino M, et al. RNA sequencing keloid transcriptome associates keloids with Th2, Th1, Th17/Th22, and JAK3-skewing. Front Immunol. 2020;11:597741.

Zhang Q, Yamaza T, Kelly AP, et al. Tumor-like stem cells derived from human keloid are governed by the inflammatory niche driven by IL-17/IL-6 axis. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(11):e7798.

Firlej E, Kowalska W, Szymaszek K, Roliński J, Bartosińska J. The role of skin immune system in acne. J Clin Med. 2022;11(6):1579.

Singh S, Khurana A, Chitkara A. Evaluation of serum levels of interleukins 6, 8, 17 and 22 in acne vulgaris: a cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol. 2023;68(2):233.

Calocer F, Ng HS, Zhu F, et al. Low socioeconomic status was associated with a higher mortality risk in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2023;29(3):466–70.

Gray-Roncal K, Fitzgerald KC, Ryerson LZ, et al. Association of disease severity and socioeconomic status in Black and white Americans with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2021;97(9):e881–9.

Yang DH, Huang JY, Chiou JY, Wei JC. Analysis of socioeconomic status in the patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(6):1194.

E.S. Group. Socioeconomic deprivation and rheumatoid disease: what lessons for the health service? ERAS Study Group. Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59(10):794–9.

Sagy I, Cohen Y, Nahum Y, Pokroy-Shapira E, Abu-Shakra M, Molad Y. Lower socioeconomic status worsens outcome of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus independently of access to healthcare. Lupus. 2022;31(5):532–40.

Håkansson KEJ, Backer V, Ulrik CS. Socioeconomic status is associated with healthcare seeking behaviour and disease burden in young adults with asthma—a nationwide cohort study. Chron Respir Dis. 2022;19:14799731221117297.

Arima J, Huang C, Rosner B, Akaishi S, Ogawa R. Hypertension: a systemic key to understanding local keloid severity. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23(2):213–21.

Ogawa R. The most current algorithms for the treatment and prevention of hypertrophic scars and keloids: a 2020 update of the algorithms published 10 years ago. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;149(1):79e–94e.

Park TH, Chang CH. Location of keloids and its treatment modality may influence the keloid recurrence in children. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26(4):1355–7.

Khan FA, Drucker NA, Larson SD, Taylor JA, Islam S. Pediatric earlobe keloids: outcomes and patterns of recurrence. J Pediatr Surg. 2020;55(3):461–4.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Third-party medical writing assistance provided by Carolyn Maskin, PhD, of Nucleus Global, Inc, was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Funding

This study and the Open Access fee were funded by Pfizer Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OJ, AS, JKP, and PG conceived and designed the study. AS participated in acquisition of the data. All authors drafted the manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual content. YJ performed statistical analysis of the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

At the time of the study, Prethibha George was an employee of Pfizer Inc and may hold stock or stock options in Pfizer Inc; Prethibha George has no current affiliation. Elena Peeva, Yuji Yamaguchi, and Oladayo Jagun are employees of and may hold stock or stock options in Pfizer Inc. Anna Swenson, Yoojin Jung, and Stefan Weiss are employees of OM1, Inc. At the time of the study, Jessica Paulus was an employee of OM1 Inc.; Jessica Paulus’ current affiliation is Ontada LLC, Boston, MA, USA. Pfizer Inc engaged and provided funding to OM1 Inc to conduct this study.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with legal and regulatory requirements, as well as with scientific purpose, value, and rigor and follows generally accepted research practices described in Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices issued by the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology, the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research guidance, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. All database records were deidentified in compliance with the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA); therefore, informed consent from patients was not needed or obtained, and approval from an institutional review board was not required.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Swenson, A., Paulus, J.K., Jung, Y. et al. Natural History of Keloids: A Sociodemographic Analysis Using Structured and Unstructured Data. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 14, 131–149 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01070-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01070-3