Abstract

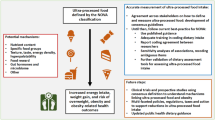

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a debilitating chronic inflammatory skin condition affecting hair follicles in flexural sites. Obesity is considered to be a risk factor for HS occurrence and thought to be associated with increased severity of HS symptoms. Here, we review the literature examining the impact of dietary factors on HS. Moreover, we propose potential mechanistic links between dietary factors and HS pathogenesis, incorporating evidence from both clinical and basic science studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition of the hair follicles. |

HS pathogenesis can be affected by multiple dietary factors, including vitamins, minerals, high fat, and carbohydrates. |

Dietary factors can affect HS by modulating inflammation. |

There is no widely accepted HS diet, but certain foods can worsen or improve inflammation in patients with HS. |

Although no dietary guidelines exist for HS, increasing understanding of dietary impacts in HS can improve patient counseling. |

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), also known as acne inversa, is a chronic autoinflammatory skin condition driven by the occlusion and subsequent rupture of the terminal hair follicle (Fig. 1). This condition is typified by painful nodules and draining abscesses that often progress to the development of dermal sinus tracts and scarring. HS lesions develop in flexural sites, including axillae, inframammary folds, and perineal sites. In addition to its painful physical manifestations, HS also places a significant burden on psychosocial functioning and quality of life, with depression, anxiety, body image, and financial strain as strong drivers of poor health-related quality of life [1]. The overall estimated prevalence of HS varies but has been reported to be as high as 4% [2, 3]. Notably, there is an increased incidence of HS in women, particularly women of color [4]. The etiology of HS is unknown; however, epigenetic factors influencing keratinocyte differentiation [5], in addition to a combination of genetic, environmental, hormonal, and lifestyle factors have been proposed to underlie the pathogenesis of HS [6].

HS also has a strong epidemiologic association with other disorders that play an important role in disease progression, namely the metabolic syndrome (MetS) and its individual constituents, such as obesity [7]. Obesity and MetS result in a basal level of chronic, systemic inflammation, often termed ‘meta-inflammation,’ that appear to be related to HS progression. While it is possible that MetS-induced inflammation drives HS [7, 8], evidence also suggests that inflammation caused by HS can contribute towards poor metabolic characteristics independent of adiposity [9].

Since MetS and HS are closely linked, weight loss represents a key lifestyle alteration that can improve HS symptoms, of which both exercise and diet are important aspects [7]. Notably, dietary factors represent key modifiable components that can control both MetS-induced inflammation and general inflammation associated with HS. Here, we review key dietary factors associated with HS progression and highlight potential mechanistic links behind diet induced inflammation and HS pathogenesis.

Materials and Methods

In this review, two authors (AS and JJ) performed independent literature searches of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science utilizing the following search terms: “hidradenitis suppurativa” OR “HS” OR “acne inversa,” AND one of the following: “diet” OR “optimal diet” OR “dietary modifications” OR “dairy” OR “high fat diet” OR “vitamin D” OR “carbohydrates OR “supplements.” Any duplicate article identified independently by these two authors was removed. While no date ranges were used, emphasis was placed on more recent studies (within the last 5 years). Only clinical studies were incorporated in the initial search. The third author (MLK) appraised the final literature selection to ensure that all included articles were directly clinically relevant to HS and diet. A total of 18 published studies describing HS and various dietary factors were included in the review (Table 1). Only articles written in English were included. All articles were synthesized into a narrative review summarizing the available evidence on dietary influences on HS while also focusing on the potential immune mediated mechanisms that underlie such influences.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Is There an Optimal Diet for HS?

Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet (MD) emphasizes the benefits of complex carbohydrates and healthy fats and has previously demonstrated important anti-inflammatory effects [10]. Two cross-sectional studies suggest the utilization of the MD for controlling HS disease activity due to the lower adherence of HS patients versus control subjects to the MD [11] and the association between MD adherence and decreased HS severity [12]. In a survey-based study, 89/744 participants identified HS symptom-alleviating foods, with vegetables, fruits, and fish comprising 78.7%, 56.2% and 42.7% of these foods, respectively [13]. Despite these results, a recent case–control study of Sardinian HS patients found no association with MD adherence and HS severity [14], demonstrating that the complex relationship between diet and HS extends beyond just a single dietary intervention.

The MD emphasizes the consumption of fruits, vegetables, fish, nuts, and healthy oils concomitantly with a low consumption of red meats, dairy and alcohol. Thus, proper adherence to the MD can promote weight loss and decrease the risk of MetS which reduces chronic systemic inflammation. Additionally, decreased simple carbohydrate intake reduces mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling and subsequent cellular proliferation in the follicular epithelium, thereby preventing the follicular occlusion cascade (described in more detail in section Low Carbohydrate/Low Dairy Diet) [12].

Low Carbohydrate/Low Dairy Diet

Reduced intake of carbohydrates and dairy have consistently been associated with HS symptom improvement. A retrospective study of 40 HS patients identified considerable improvement in Hurley stage among seven patients who were placed on a low dairy/low carbohydrate diet [15]. In another study, compared to a non-diet-restricted control group, clinical improvement was observed in 83% of 47 HS patients on a dairy-free diet [16]. Further, foods exacerbating symptoms were identified in 237/728 HS patients in a survey-based study. Of the exacerbating foods, 67.9% were sweets, 51.1% were bread/pasta, and 50.6% were dairy products [13].

Diets high in simple carbohydrates and dairy products have been proposed to affect the initial stages of HS pathogenesis, namely, the occlusion and rupture of hair follicles. One hypothesis postulates that simple carbohydrates and the breakdown products of dairy, e.g. casein and whey, increase insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) production. This results in the activation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway, and downstream androgen receptor stimulation resulting in hyperkeratinization contributing to follicular occlusion [17] (Fig. 2). Elevated mTOR signaling in lesional skin of patients with HS, compared with non-lesional skin, has been described [18]. Furthermore, mTOR signaling regulates the differentiation of T helper 17 (Th17) cells [19], an important pro-inflammatory subset of T helper cells involved in the recruitment of inflammatory neutrophils that have been found to drive HS progression. Interestingly, metformin has been shown to be associated with improved clinical responses in a subset of HS patients [20], possibly by ameliorating insulin resistance and reducing mTOR signaling [21].

Mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling in hidradenitis suppurativa. Simple carbohydrates and breakdown products of dairy (casein & whey) increase insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels. This in turn activates both mTOR signaling and androgen receptor signaling. Androgen receptor activation stimulates hyper-keratinization and follicular occlusion; mTOR pathway activation stimulates T helper cell 17 (Th17) cell recruitment and worsening of inflammation

High Fat Diet

A high fat diet has also been reported to exacerbate HS symptoms, with 42.2% of 237 HS patients reporting exacerbated symptoms when eating high fat foods [13]. High fat diets can induce gut dysbiosis, resulting in a reduction in antimicrobial peptides and an increase in inflammatory cytokines, e.g. TNF-a, IL-1B, and IL-6 [22]. These cytokines recruit inflammatory neutrophils and monocytes, which produce matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). MMPs have been implicated in the worsening of HS because of the remodeling of the extracellular matrix that allows for eventual sinus tract development. Additionally, other studies [23] demonstrate that a high fat diet can contribute to neutrophilic folliculitis by promoting hyperkeratosis and neutrophilic infiltration of hair follicles.

Brewer’s Yeast-Free Diet

Evidence also suggests a role for brewer’s yeast in worsening HS symptoms. Among post-operative HS patients with a specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) reaction to brewer’s yeast, those who stayed on a brewer’s yeast-free diet for 12 months achieved stabilization of symptoms and regression of lesions. Recurrence only occurred after consumption of brewer’s yeast products, such as beer [24]. In another study, among 37 patients following a yeast exclusion diet, 70% reported an improvement in HS symptoms, with 87% of patients experiencing a recurrence of skin lesions in under 1 week following resumption of yeast consumption [25].

Thus, ingestion of yeast products may worsen HS symptomatology, especially in patients with an immune sensitivity to yeast due to anti-Saccharyomyces cervisiae IgG (ASCA). Associations between ASCAs and systemic inflammation as measured by C-reactive protein (CRP) have also been reported [26], pointing towards the immunogenic nature of yeast products. Thus, the stimulation of both the local and systemic immune response following yeast ingestion, especially in individuals with yeast sensitivities, may subsequently worsen HS symptomatology.

Is There a Role for Supplementation with Zinc, Vitamin D, or Vitamin B12?

Zinc

Zinc supplementation has also been associated with a reduction in HS symptoms. One pilot study of 22 Hurley stage I and II HS patients who were treated with 90 mg of zinc gluconate per day resulted in eight complete remissions (CR) and 14 partial remissions (PR) at an average follow-up of 23.7 months [27]. A reduction in zinc dosage to 30–60 mg resulted in disease relapse in those patients with CR, but recurrences disappeared upon increasing the zinc dosage. This result indicates a possible suppressive, rather than curative, nature of zinc on HS.

A separate retrospective study identified that the combination 90 mg/day zinc gluconate and topical triclosan 2% twice daily for 3 months significantly reduced disease severity, erythema, and inflammatory nodules in 66 Hurley stage I and II HS patients [28]. Additionally, in a case–control study of 122 HS patients and 122 controls, low serum zinc levels were found to be more prevalent in HS patients (odds ratio [OR]adjusted = 6.7, p < 0.001), with low serum zinc being associated with severe Hurley stage III HS (ORadjusted = 4.4, p < 0.001) and number of affected sites ≥ 3 (ORadjusted = 2.4, p = 0.042). This result indicates that a low serum zinc level is not only associated with HS but may also be a marker of disease severity [29]. Finally, a study investigating the utility of zinc and nicotinamide as maintenance therapy in patients with mild to moderate HS who had been previously treated with oral tetracyclines found that treated patients experienced a significant reduction in acute flares, and had a significantly longer disease-free survival compared to controls [30].

The mechanistic role of zinc in improving HS symptoms may be related to its effects in immune system modulation. Zinc deficiency has been linked to an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS), a key mediator of oxidative stress and inflammation, and to matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), in addition to inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [31], which are commonly implicated in the inflammatory cascade of HS. Additionally, zinc supplementation can reduce inflammatory Th17 responses and neutrophil recruitment while inducing immune suppression through regulatory T cell (T-reg) recruitment [32,33,34].

Vitamin D

Vitamin D has an established role in maintaining and regulating the physiological properties of the skin, from barrier integrity to immune modulation. Evidence has emerged regarding vitamin D deficiency and HS [35, 36], with one study demonstrating that vitamin D deficiency was associated with HS severity: in a pilot of 14 HS patients, supplementation with vitamin D improved symptoms, significantly reducing the number of nodules at 6 months (p = 0.011) [36]. Thus, an inverse correlation between serum vitamin D levels (25-hydroxycholecalciferol) and HS disease severity may exist. Further, a case–control study conducted in Jordan found that patients with HS were more likely to have vitamin D deficiency compared to healthy controls [37]. Finally, a study using whole-exome sequencing identified that genetic dysfunctions in vitamin D metabolism are key aspects in the pathogenesis of HS and other neutrophilic dermatoses [38].

One potential mechanism of vitamin D’s effects on HS relates to vitamin D’s effects on skin immunology. Hypovitaminosis D impacts the production of cutaneous antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), resulting in excess microbial buildup in the skin triggering inflammation [39]. Further, vitamin D induces cutaneous immunosuppression by increasing T-reg levels in skin-draining lymph nodes [40], as well as downregulating the infiltration of effector helper T cells into the skin [41]. A recent study also identified an inverse correlation between vitamin D levels and systemic inflammation, measured with CRP levels [42], lending further support towards the role of hypovitaminosis D in producing excess inflammation.

Homocysteine and Vitamin B12

One prospective case–control study described a higher prevalence of hyperhomocysteinemia in 26 HS patients (mean ± standard deviation, 16.71% ± 10.17%) compared to 26 healthy controls (12.96% ± 8.16%; p = 0.048), with a significant correlation of plasma homocysteine and increased severity of HS symptoms (p < 0.01; r = 0.55) [43]. Administration of high-dose vitamin B12, which is a critical factor in the breakdown of homocysteine to methionine, in two patients with HS and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) prevented the recurrence of suppuration [44]. Neither patient had a measurable vitamin B12 deficiency, and one of the patients experienced a dose-dependent improvement. In the same study, of an additional ten IBD patients with various suppurative dermatoses who received high-dose vitamin B12, six patients benefitted from the treatment, indicating a potential role for B12 in IBD patients with cutaneous suppurative manifestations [44].

The pro-inflammatory role of hyperhomocysteinemia [45] may explain the possible connection between elevated plasma homocysteine level and increased severity of HS symptoms. Homocysteine has been demonstrated to play a key role in the pro-inflammatory effects of cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-18, as well as MMPs [45]. Homocysteine has also been shown to increase ROS generation via NADPH oxidase stimulation, a key component in both neutrophilic function and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [46]. Since vitamin B12 regulates homocysteine levels, the beneficial effects of vitamin B12 supplementation on HS symptoms may be due to a reduction in homocysteine and its pro-inflammatory effects. It is still unclear whether vitamin B12’s effects on homocysteine are the only notable mechanism in controlling inflammation associated with HS symptoms.

Discussion

While no single diet exists for HS, research does suggest improvements in HS symptoms for some patients with certain diets (e.g. MD), and additional research continues to be conducted on other dietary patterns, such as time-restricted fasting and HS symptom improvement [47]. However, dietary factors are key contributors to HS disease progression, and dietary modifications can play an important role in alleviating disease. It is still uncertain as to the exact mechanisms behind each dietary factor, and whether they impact all HS patients the same. However, based on current evidence, there are multiple diet-induced immune dysregulations that can occur and worsen HS symptoms. Most current evidence relies on observational data and limited sample sizes, necessitating additional work through clinical trials to further our understanding of dietary influences in HS disease progression. Unfortunately, no clear-cut guidelines exist to ensure that modifications to diet occur in a systematic, personalized manner, However, healthcare providers should continue to maintain awareness of how diet impacts their HS patient’s symptoms and personalize management accordingly.

Conclusion

Current evidence suggests a role for dietary factors in affecting HS progression through the inflammatory cascade. Although no concrete guidelines exist for diet in HS, understanding the associations between diet and HS can improve patient counseling and well-being. Further research is necessary to delineate causal mechanisms between dietary factors and HS.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Weigelt MA, Milrad SF, Kirby JRS, Lev-Tov H. Psychosocial impact of hidradenitis suppurativa: a practical guide for clinicians. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(4):1861–8.

Ingram JR. The epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(6):990–8.

Nguyen TV, Damiani G, Orenstein LV, Hamzavi I, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: an update on epidemiology, phenotypes, diagnosis, pathogenesis, comorbidities and quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(1):50–61.

Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, Lin G, Strunk A. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(8):760–4.

Moltrasio C, Romagnuolo M, Marzano AV. Epigenetic mechanisms of epidermal differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;3(9):4874. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23094874.

Rosi E, Fastame MT, Scandagli I, et al. Insights into the pathogenesis of HS and therapeutical approaches. Biomedicines. 2021;9(9):1168.

Mintoff D, Benhadou F, Pace NP, Frew JW. Metabolic syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiological, molecular, and therapeutic aspects. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61(10):1175–86.

Ergun T. Hidradenitis suppurativa and the metabolic syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(1):41–7.

Mintoff D, Agius R, Fava S, Pace NP. Investigating adiposity-related metabolic health phenotypes in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Med. 2023;12(14):4847.

Casas R, Urpi-Sardà M, Sacanella E, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of the Mediterranean diet in the early and late stages of atheroma plaque development. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:3674390.

Barrea L, Fabbrocini G, Annunziata G, et al. Role of nutrition and adherence to the Mediterranean diet in the multidisciplinary approach of hidradenitis suppurativa: evaluation of nutritional status and its association with severity of disease. Nutrients. 2018;11(1):57.

Lorite-Fuentes I, Montero-Vilchez T, Arias-Santiago S, Molina-Leyva A. Potential benefits of the Mediterranean diet and physical activity in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study in a Spanish population. Nutrients. 2022;14(3):551.

Fernandez JM, Marr KD, Hendricks AJ, et al. Alleviating and exacerbating foods in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6): e14246.

Velluzzi F, Anedda J, Pisanu S, et al. Mediterranean diet, lifestyle and quality of life in Sardinian patients affected with Hidradenitis suppurativa. J Public Health Res. 2021;11(2):2706. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2021.2706.

Kurzen H, Kurzen M. Secondary prevention of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Rep. 2019;11(2):8243.

Danby FW. Diet in the prevention of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5, Supplement 1):S52–4.

Maarouf M, Platto JF, Shi VY. The role of nutrition in inflammatory pilosebaceous disorders: implication of the skin-gut axis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60(2):e90–8.

Monfrecola G, Balato A, Caiazzo G, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin, insulin resistance and hidradenitis suppurativa: a possible metabolic loop. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(9):1631–3.

Ren W, Yin J, Duan J, et al. mTORC1 signaling and IL-17 expression: defining pathways and possible therapeutic targets. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46(2):291–9.

Jennings L, Hambly R, Hughes R, Moriarty B, Kirby B. Metformin use in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31(3):261–3.

Amin S, Lux A, O’Callaghan F. The journey of metformin from glycaemic control to mTOR inhibition and the suppression of tumour growth. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(1):37–46.

Molnar J, Mallonee CJ, Stanisic D, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa and 1-carbon metabolism: role of gut microbiome, matrix metalloproteinases, and hyperhomocysteinemia. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1730.

Nakamizo S, Honda T, Sato T, et al. High-fat diet induces a predisposition to follicular hyperkeratosis and neutrophilic folliculitis in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(2):473-485.e10.

Cannistrà C, Finocchi V, Trivisonno A, Tambasco D. New perspectives in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: surgery and brewer’s yeast-exclusion diet. Surgery. 2013;154(5):1126–30.

Aboud C, Zamaria N, Cannistrà C. Treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: surgery and yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)-exclusion diet. Results after 6 years. Surgery. 2020;167(6):1012–5.

Assan F, Gottlieb J, Tubach F, et al. Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae IgG and IgA antibodies are associated with systemic inflammation and advanced disease in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(2):452-455.e5.

Brocard A, Knol A-C, Khammari A, Dréno B. Hidradenitis suppurativa and zinc: a new therapeutic approach. A pilot study. Dermatology. 2007;214(4):325–7.

Hessam S, Sand M, Meier NM, Gambichler T, Scholl L, Bechara FG. Combination of oral zinc gluconate and topical triclosan: an anti-inflammatory treatment modality for initial hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84(2):197–202.

Poveda I, Vilarrasa E, Martorell A, et al. Serum zinc levels in hidradenitis suppurativa: a case-control study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(5):771–7.

Molinelli E, Brisigotti V, Campanati A, et al. Efficacy of oral zinc and nicotinamide as maintenance therapy for mild/moderate hidradenitis suppurativa: a controlled retrospective clinical study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):665–7.

Wessels I, Maywald M, Rink L. Zinc as a gatekeeper of immune function. Nutrients. 2017;9(12):1286.

Rosenkranz E, Maywald M, Hilgers R-D, et al. Induction of regulatory T cells in Th1-/Th17-driven experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by zinc administration. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;29:116–23.

Rosenkranz E, Metz CHD, Maywald M, et al. Zinc supplementation induces regulatory T cells by inhibition of Sirt-1 deacetylase in mixed lymphocyte cultures. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016;60(3):661–71.

George MM, Vignesh KS, Landero Figueroa JA, Caruso JA, Deepe GS. Zinc induces dendritic cell tolerogenic phenotype and skews regulatory T cell—Th17 balance. J Immunol. 2016;197(5):1864–76.

Kelly G, Sweeney CM, Fitzgerald R, et al. Vitamin D status in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(6):1379–80.

Guillet A, Brocard A, Bach Ngohou K, et al. Verneuil’s disease, innate immunity and vitamin D: a pilot study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(7):1347–53.

Seetan K, Eldos B, Saraireh M, et al. Prevalence of low vitamin D levels in patients with Hidradenitis suppurativa in Jordan: a comparative cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2022;17(3): e0265672.

Brandao L, Moura R, Tricarico PM, et al. Altered keratinization and vitamin D metabolism may be key pathogenetic pathways in syndromic hidradenitis suppurativa: a novel whole exome sequencing approach. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;99(1):17–22.

Umar M, Sastry KS, Al Ali F, Al-Khulaifi M, Wang E, Chouchane AI. Vitamin D and the pathophysiology of inflammatory skin diseases. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2018;31(2):74–86.

Gorman S, Geldenhuys S, Judge M, Weeden CE, Waithman J, Hart PH. Dietary vitamin D increases percentages and function of regulatory T cells in the skin-draining lymph nodes and suppresses dermal inflammation. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:1426503.

Yamanaka K, Dimitroff CJ, Fuhlbrigge RC, et al. Vitamins A and D are potent inhibitors of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(1):148-157.e3.

Moltrasio C, Tricarico PM, Genovese G, Gratton R, Marzano AV, Crovella S. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D serum levels inversely correlate to disease severity and serum C-reactive protein levels in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatol. 2021;48(5):715–7.

Marasca C, Donnarumma M, Annunziata MC, Fabbrocini G. Homocysteine plasma levels in patients affected by hidradenitis suppurativa: an Italian experience. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44(3):e28–9.

Mortimore M, Florin THJ. A role for B12 in inflammatory bowel disease patients with suppurative dermatoses? An experience with high dose vitamin B12 therapy. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4(4):466–70.

Lazzerini PE, Capecchi PL, Selvi E, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia, inflammation and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;6(7):503–9.

Au-Yeung KKW, Woo CWH, Sung FL, Yip JCW, Siow YL, Karmin O. Hyperhomocysteinemia activates nuclear factor-κB in endothelial cells via oxidative stress. Circ Res. 2004;94(1):28–36.

Damiani G, Mahroum N, Pigatto PDM, et al. The safety and impact of a model of intermittent, time-restricted circadian fasting (“Ramadan Fasting”) on hidradenitis suppurativa: insights from a multicenter, observational, cross-over, pilot, exploratory study. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1781.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Articles were independently searched for and reviewed by Alan Shen and Jessica Johnson. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Alan Shen, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Project oversight was provided by Michelle Lynn Kerns. Significant edits for clinical applicability were performed by Michelle Lynn Kerns. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, A.S., Johnson, J.S. & Kerns, M.L. Dietary Factors and Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 13, 3007–3017 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01056-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01056-1