Abstract

Based on clinical trials of systemic treatments in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) reported between 2014 and 2023, we used linear regression to investigate relationships between baseline Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores and (1) study start date, (2) EASI response, and (3) rescue medication rates. Analysis 1 was conducted with all patients from monotherapy and combination therapy trials; analyses 2 and 3 used monotherapy trial placebo arms. Across 32 trials with a baseline inclusion criterion of EASI ≥ 16, baseline mean EASI scores decreased with study start date. The lowest and highest baseline mean EASI scores were 25.1 and 33.6 (median 21.1 and 30.5), reported for the WW001 Phase 2 trial of rademikibart (formerly CBP-201; start date, July 2020) and the SOLO1 Phase 3 trial of dupilumab (start date, December 2014), respectively. In placebo arms, lower baseline EASI scores tended to be associated with greater percent reductions in EASI scores at Week 16 and less rescue medication usage. The WW001 trial placebo arm had the lowest baseline EASI score (mean 25.2; median 22.1), lowest rescue medication rate (14.3%), and a large reduction in least squares mean EASI scores (− 39.7%) at Week 16. In summary, baseline mean EASI scores have decreased across clinical trials conducted during the last decade. Less severe AD at baseline tended to be associated with greater placebo response and less use of rescue medications in placebo arms. Intertrial differences in variables, such as baseline AD severity, limit the validity of indirectly comparing clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In atopic dermatitis (AD) clinical trials, baseline mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores have decreased across clinical trials conducted during the last decade. |

Less severe AD at baseline tended to be associated with greater placebo response and less use of rescue medications in placebo arms. |

Care must be used when comparing across trials or using meta-analysis techniques as intertrial differences in variables, such as baseline AD severity, limit the validity of indirectly comparing clinical trials. |

Introduction

Many clinical trials of biologic and small-molecule systemic therapies for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) are either in progress or have been completed in the last decade, with approvals granted or expected for several medications including dupilumab, tralokinumab, lebrikizumab, abrocitinib, and upadacitinib in the US [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Other medications that show promise as systemic treatments for moderate-to-severe AD include rademikibart (formerly CBP-201), amlitelimab, spesolimab, and baricitinib [9,10,11,12,13,14].

Indirect comparisons of AD trials are complicated by differences in various aspects of study design, conduct, and statistical analyses [15], and few AD medications were investigated in head-to-head clinical trials [7, 16, 17]. Efforts are ongoing to standardize the design and reporting of future AD clinical trials [18].

Silverberg et al. [15] recently used their experience as expert clinical trialists to identify and rank 22 key study design parameters based on the likely impact of each parameter on the efficacy outcomes of AD clinical trials. Three of the most important study design parameters were “inclusion criteria such as disease severity,” for example baseline Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores, “rules for rescue treatment,” and “missing data handling” [15].

In this review paper, we compare key variables in recent AD trials of systemic biologic and small molecule therapies and discuss their potential impact on efficacy outcomes. In particular, we investigated whether relationships exist between baseline AD severity (as judged by EASI scores) and study start date, placebo response, and use of rescue medication. In doing so, we aim to address the validity of indirectly comparing the efficacy outcomes of AD trials.

Methods

This narrative review article is based on recently completed and ongoing clinical trials, available on PubMed. We included randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, international, Phase 2/2b or 3 clinical trials in adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD reported between July 2014 and March 2023.

Relationships were assessed between baseline EASI scores and (1) study start date, (2) percent reduction in EASI score, and (3) rescue medication usage rates. If available in published literature or on clinicaltrials.gov, mean EASI scores from each study were included in the analyses; if means were unavailable, median EASI scores were to be included. Analysis 1 was conducted with all patients from monotherapy and combination therapy AD trials conducted in international settings. Clinical trials were included in Analysis 1 if they had the inclusion criterion of EASI score ≥ 16 at baseline; sensitivity analyses were also conducted, in which trials with baseline EASI score inclusion criteria < or > 16 were also eligible. Analyses 2 and 3 were conducted using the placebo arms in AD trials of systemic monotherapies.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Statistics

All relationships were analyzed by simple linear regression in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline EASI Scores Versus Study Start Date in the Overall Populations of AD Clinical Trials

Thirty-three Phase 2 and 3 clinical trials of systemic mono or combination therapies, each with baseline inclusion criterion of EASI score ≥ 16, were eligible for the analysis of mean baseline EASI scores versus study start date [1,2,3, 5,6,7,8,9, 11, 16, 17, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Each clinical trial began between the years 2013 and 2020 and was published between 2014 and 2023. The estimated pooled mean EASI score across the 32 trials was 29.9.

Across the 32 trials, lower baseline mean EASI scores were associated with more recent study start dates (Fig. 1). The lowest and highest baseline mean EASI scores were 25.1 (median 21.1) and 33.6 (median 30.5), reported for the WW001 Phase 2 trial of rademikibart monotherapy, which began in July 2020, and SOLO1, a Phase 3 trial of dupilumab, which began in December 2014.

Baseline mean EASI scores for the overall populations in AD clinical trials with an EASI inclusion criterion of ≥ 16 at baseline. If mean values and study start dates were not available in published papers, they were obtained from clinicaltrials.gov. Abro abrocitinib, Ast astegolimab, AD atopic dermatitis, Bar baricitinib, Combo combination therapy, CS topical corticosteroid, Dupi dupilumab, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, Etra etrasimod; Lebri, lebrikizumab, Mono monotherapy, Nemo nemolizumab, Ph phase, Rade rademikibart, Ris risankizumab, Roca rocatinlimab, Tez Tezepelumab, Tralo tralokinumab, Upa upadacitinib

Seven trials were excluded from the main analysis because their baseline EASI score inclusion criterion was higher (two trials [4, 35]) or lower (five trials [36,37,38,39,40]) than 16. As in the main analysis (Fig. 1), inclusion of these seven trials in three sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Figs. 1–3) did not affect the overall finding of a reduction in baseline EASI scores across the trials.

Baseline EASI Scores Versus Percent Reductions in EASI Scores at Week 16 in the Placebo Arms of Monotherapy Trials

Based on 23 eligible AD monotherapy trials [1,2,3, 5, 8, 11, 20, 23, 24, 26,27,28,29, 31, 32, 41,42,43], lower baseline EASI scores in the placebo arms tended to be associated with higher placebo response in EASI scores at Week 16 (Fig. 2). The WW001 Phase 2 trial of rademikibart, the study with the lowest baseline EASI score (mean 25.2; median 22.1) in its placebo arm, reported least squares mean (LSM) reduction from baseline in EASI score at Week 16 of 39.7% for placebo. The Phase 2 trial of dupilumab reported a baseline mean EASI score of 32.9 and LSM reduction from baseline in EASI score at Week 16 of only 18.1% for placebo. Although an association was observed between baseline EASI score and placebo response (Fig. 2), it should be note that SOLO1 and SOLO2 (the two trials with the highest baseline mean EASI scores in their placebo arms; 34.5 and 33.6) reported sizable reductions in EASI score of 37.6% and 30.9% in these arms. This is compatible with the potential for numerous factors other than baseline EASI scores to also influence efficacy findings [15, 44,45,46].

EASI scores at baseline vs percent reductions in EASI scores at Week 16 in placebo arms in AD clinical trials of systemic monotherapies. If mean values were not available in published papers, they were obtained from clinicaltrials.gov. Ast astegolimab, AD atopic dermatitis, Bar baricitinib, Dupi dupilumab, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, Lebri lebrikizumab, Nemo nemolizumab, Ph phase, Rade rademikibart, Tez tezepelumab, Tralo tralokinumab, Upa upadacitinib

Of the 23 trials in the analysis of baseline EASI scores vs response in the placebo arms (Fig. 2), 17 studies were for injectables. The relationship of lower baseline EASI scores being associated with greater percent change in EASI scores was also observed for the 17 trials with injected placebo and, although limited to just six trials, also for oral placebo.

One paper identified in the search (which was ineligible for inclusion in the analysis of EASI scores in placebo arms because of concomitant use of topical corticosteroids) reported post hoc analyses by baseline EASI score (< 24 and ≥ 24 subgroups) in two Phase 3 dupilumab trials (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS and LIBERTY AD CAFÉ) [47]. LSM reductions in EASI scores from baseline at Week 16 were considerably larger in the baseline EASI < 24 versus ≥ 24 subgroups (54.8% vs 38.9%, respectively) in the placebo arm, a percentage point difference of 15.9, whereas the percentage point difference between the baseline subgroups was only 2.6 in the dupilumab active treatment arm (75.9% vs 78.5%). These results suggest that baseline EASI score may impact efficacy response to a greater extent in placebo than in active treatment arms, thus affecting placebo-adjusted efficacy responses.

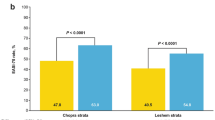

Baseline EASI Scores Versus Rescue Medication Usage at Week 16 in Monotherapy Trials

Based on 14 eligible AD monotherapy trials that allowed and reported rescue medication usage across 16 weeks of treatment [1, 3, 5, 8, 11, 20, 24, 32, 41], lower baseline EASI scores were associated with smaller proportions of patients requiring this intervention in the placebo arms (Fig. 3). In the 14 studies, at least 36% of patients were treated with rescue medication per placebo arm, except for the WW001 Phase 2 trial of rademikibart (14.3%), which also reported the lowest baseline mean EASI score (25.2) in its placebo arm.Footnote 1 The proportions of patients using rescue medication in placebo arms was particularly high in three Phase 3 dupilumab trials (> 50%) and in three Phase 3 baricitinib trials (> 64%).

EASI scores at baseline vs rescue medication usage in placebo arms in AD clinical trials of systemic monotherapies with 16-week treatment periods. If mean values were not available in published papers, they were obtained from clinicaltrials.gov. Clinical trials were included if they allowed use of rescue medication and reported rescue medication rates. AD atopic dermatitis, Bar baricitinib, Dupi dupilumab, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, Lebri lebrikizumab, Ph phase, Rade rademikibart, Tralo tralokinumab, Upa upadacitinib

Discussion

Our mini review of 32 AD clinical trials that began between 2013 and 2020, published between 2014 and 2023, demonstrates that baseline disease severity (based on mean EASI scores) varied considerably and was less severe in more recent studies. Our results also indicate that patients with less severe AD at baseline may be more likely to respond to placebo and are less likely to use rescue medication. The WW001 Phase 2 trial of rademikibart had the patient population with the least severe AD (based on EASI scores), compatible with a high placebo response rate (39.7% reduction in EASI score) and a low rate of rescue medication use in the placebo arm.

Considerable variability in baseline disease severity inclusion criteria, and use of different scales to assess severity, were previously reported in a systematic review of AD trials published up to 2016 [48]. However, in our review, even though the 32 clinical trials had the same inclusion criteria for moderate-to-severe AD (EASI score ≥ 16, IGA score ≥ 3, BSA ≥ 10%), baseline EASI scores differed markedly between the studies. A likely explanation is that approval of medications for moderate-to-severe AD in the last 6 years, notably dupilumab, reduced the patient population in need of clinical trials. An International Eczema Council (IEC) survey-based position statement suggested that patients are reluctant to participate in placebo arms, particularly given the recent availability of more effective treatments, resulting in selection bias [44]. Before their approval, physicians probably enrolled the worst affected patients in clinical trials. Now clinical trials of potential AD treatments likely include a patient population with more diverse severity, such as people who cannot afford effective medication or who are not covered adequately by medical insurance. The IEC position statement suggested that patients with milder AD, who are not reimbursed, may tolerate and respond more to placebo; this scenario is supported by our findings [44].

In our review, we found a tendency for lower baseline mean EASI scores to be associated with greater EASI responses in the placebo arms. Our analysis was based on trials published between 2014 and 2023, with patients diagnosed with moderate-to-severe AD. The importance of considering the potential impact of baseline disease severity on treatment response is also highlighted by a meta-analysis of 64 randomized controlled trials of AD, which were published between January 2007 and January 2018, and included patients with mild disease. Lee et al. [46] demonstrated that EASI responses in placebo arms were significantly greater when baseline EASI scores were mild to moderate. It is unclear how baseline AD severity affects EASI responses in the active treatment arms of AD clinical trials; this is an underexplored area, although a post hoc analysis of two Phase 3 trials of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS and LIBERTY AD CAFÉ) [47] suggests that baseline EASI score may not have the same magnitude of impact on responses in placebo and active treatment arms.

In addition to clinical explanations (e.g., patients with milder AD not being reimbursed, resulting in better tolerance and greater response to placebo), mathematics may also explain the tendency for lower baseline mean EASI scores to be associated with greater EASI responses in the placebo arms. If starting at a low baseline EASI score (e.g., 20 points), a small decrease in absolute EASI score (e.g., by 10 points) would result in a 50% decrease, whereas the same 10-point decrease from a baseline EASI score of 30 points would result in a smaller 33% decrease.

A tangled web of dozens of variables may complicate indirect comparisons; Silverberg et al. [15] ranked “22 key study parameters” for likely impact on efficacy outcomes. Lee et al. [46] noted associations between placebo response and sex ratio and, unsurprisingly, bias in unblinded trials; neither variable was one of the 22 study design parameters ranked by Silverberg et al. [15]. In our review, another notable factor that would affect efficacy outcomes, use of rescue medication, varied considerably across AD trials and, in the placebo arms, was associated with baseline EASI score. With placebo, use of rescue medication was particularly low in the WW001 (14.3%) and ADVISE (10.9%) Phase 2 trials of rademikibart and etrasimod, respectively, and high in the baricitinib BREEZE-AD2 Phase 3 trial (76.6%). Rescue medication use may impact efficacy outcomes in several respects, for instance: (1) in non-responder imputation (NRI) analyses, classifying these patients as non-responders would likely reduce response rates; (2) if patients are included in analyses after receiving rescue medication, this would inflate response rates [15]. The authors of the BREEZE-AD5 Phase 3 trial speculated that, compared with BREEZE-AD1/2, lower baseline AD severity and higher rescue medication rates may account for greater efficacy in BREEZE-AD5 [24].

Adding to the complication is the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which undoubtably affected the conduct of clinical trials in general [49, 50]. WW001 was the only placebo-controlled, randomized, international, AD monotherapy trial that we found to be conducted entirely during the COVID-19 pandemic. Movement restrictions in place during the pandemic may have increased discontinuations in the WW001 Phase 2 trial, although none were attributed directly to COVID-19 infection [11]. In WW001, discontinuation rates were 13%–29% across the rademikibart arms and placebo arm [11], relative to 6–19% in dupilumab monotherapy Phase 3 trials [1, 2, 41]. The effects of discontinuations on efficacy responses may depend on the analysis technique used to handle missing data (such as NRI and last observation carrier forward) [15] and reasons for discontinuations.

In the current mini review, analysis of baseline EASI scores versus percent reduction in EASI scores in the placebo arms was conducted at one time point—Week 16 of treatment. The lack of extrapolation beyond Week 16 in this analysis and lack of follow-up beyond Week 16 in the source trials are limitations as it is unclear whether percent reductions in EASI score were maximal at this time point; for instance, EASI score reductions plateaued at Week 16 in the placebo and dupilumab arms of the SOLO2 trial [1], whereas EASI responses did not plateau in any arm in the WW001 trial of rademikibart [11]. Another potential limitation is that our mini review did not follow a systematic approach; however, the methodology used was suitable to identify > 30 AD trials that were eligible for these analyses and to highlight the intertrial variability that complicates indirect comparisons.

In summary, indirect comparisons are hampered by a vast array of variables that differ between recent AD clinical trials and likely affect efficacy outcomes. Efforts to standardize the design and reporting of AD clinical trials are ongoing [18]. However, in our review, even when one of these variables (disease severity inclusion criteria) was reported as being the same across the trials, actual baseline EASI scores differed, tending to be lower in more recent trials, and may have had a considerable impact on efficacy outcomes, as suggested by potential associations with placebo response and use of rescue medication. Several aspects of the WW001 trial of rademikibart hamper indirect comparisons with the other trials; the WW001 patient population had the least severe AD at baseline and low rates of rescue medication use, and conduct during the COVID-19 pandemic likely affected clinic visit attendance and discontinuations [11]. We conclude that the plethora of variables and study design parameters that can differ between the studies may greatly limit the validity of indirectly comparing the outcomes of AD clinical trials.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

Another trial (ADVISE Phase 2, etrasimod), which was excluded from this analysis because of a 12-week treatment period, also reported a low rate of rescue medication usage (10.9%) and low baseline mean EASI score (25.7) in the placebo arm.

References

Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, Cork MJ, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335–48.

Thaçi D, Simpson EL, Beck LA, Bieber T, Blauvelt A, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical treatments: a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2016;387:40–52.

Guttman-Yassky E, Blauvelt A, Eichenfield LF, Paller AS, Armstrong AW, Drew J, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab, a high-affinity interleukin 13 inhibitor, in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2b randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:411.

de Bruin-Weller M, Thaçi D, Smith CH, Reich K, Cork MJ, Radin A, et al. Dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin A or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: a placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical t. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:1083–101.

Simpson EL, Lacour J-P, Spelman L, Galimberti R, Eichenfield LF, Bissonnette R, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to topical corticosteroids: results from two randomized monotherapy phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:242–55.

Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Thyssen JP, Gooderham M, Chan G, Feeney C, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:863.

Blauvelt A, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, Costanzo A, De Bruin-Weller M, Barbarot S, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib vs dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1047.

Silverberg JI, Guttman-Yassky E, Thaçi D, Irvine AD, Stein Gold L, Blauvelt A, et al. Two phase 3 trials of lebrikizumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:1080–91.

Bieber T, Reich K, Paul C, Tsunemi Y, Augustin M, Lacour J-P, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib in combination with topical corticosteroids in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with inadequate response, intolerance or contraindication to ciclosporin: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trial (BREEZE-AD4). Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:338–52.

Weidinger S, Cork M, Reich A, Bieber T, Gilbert S, Brennan N, et al. A Phase 2a study of KY1005, a novel non-depleting anti-OX40Ligand (OX40L) mAb in patients with moderate to severe AD. EADV 2021.

Strober B, Feinstein B, Xu J, Guttman-Yassky E, Silverberg JI, Simpson E, et al. Efficacy and safety of CBP-201 in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD): a phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (CBP-201-WW001). Maui Derm 2022.

Silverberg JI, Strober B, Feinstein B, Xu J, Gutman-Yassky E, Simpson EL, et al. Efficacy and safety of rademikibart (CBP-201), a next-generation monoclonal antibody targeting IL-4Ralpha, in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 randomized trial (CBP-201-WW001). Manuscript submitted.

Wang J, White J, Sansone KJ, Spelman L, Sinclair R, Yang X, et al. Rademikibart (CBP-201), a next-generation monoclonal antibody targeting human IL-4Ralpha: two phase 1 randomized trials, in healthy individuals and patients with atopic dermatitis. Manuscript accepted for publication in Clin Transl Sci.

Bissonnette R, Abramovits W, Saint-Cyr Proulx É, Lee P, Guttman-Yassky E, Zovko E, et al. Spesolimab, an anti-interleukin-36 receptor antibody, in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Results from a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIa study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37:549–57.

Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Armstrong AW, de Bruin-Weller MS, Irvine AD, Reich K. Expert perspectives on key parameters that impact interpretation of randomized clinical trials in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:1–11.

Reich K, Thyssen JP, Blauvelt A, Eyerich K, Soong W, Rice ZP, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib versus dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400:273–82.

Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, Thaçi D, Paul C, Pink AE, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101–12.

Chalmers JR, Thomas KS, Apfelbacher C, Williams HC, Prinsen CA, Spuls PI, et al. Report from the fifth international consensus meeting to harmonize core outcome measures for atopic eczema/dermatitis clinical trials (HOME initiative). Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:e332–41.

Reich K, Kabashima K, Peris K, Silverberg JI, Eichenfield LF, Bieber T, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib combined with topical corticosteroids for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1333.

Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, Papp KA, Pangan AL, Blauvelt A, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. The Lancet. 2021;397:2151–68.

Silverberg JI, Toth D, Bieber T, Alexis AF, Elewski BE, Pink AE, et al. Tralokinumab plus topical corticosteroids for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from the double-blind, randomized, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III ECZTRA 3 trial*. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:450–63.

Simpson EL, Sinclair R, Forman S, Wollenberg A, Aschoff R, Cork M, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (JADE MONO-1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2020;396:255–66.

Guttman-Yassky E, Thaçi D, Pangan AL, Hong HC, Papp KA, Reich K, et al. Upadacitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: 16-week results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:877–84.

Simpson EL, Forman S, Silverberg JI, Zirwas M, Maverakis E, Han G, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Results from a randomized monotherapy phase 3 trial in the United States and Canada (BREEZE-AD5). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:62–70.

Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, Cather JC, Weisman J, Pariser D, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2017;389:2287–303.

Emma Guttman-Yassky. Safety and efficacy of tezepelumab in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results of a phase 2b randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. 2022.

Merola JF, Bagel J, Almgren P, Røpke MA, Lophaven KW, Vest NS, et al. Tralokinumab does not impact vaccine-induced immune responses: Results from a 30-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:71–8.

Guttman-Yassky E, Simpson EL, Reich K, Kabashima K, Igawa K, Suzuki T, et al. An anti-OX40 antibody to treat moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b study. The Lancet. 2023;401:204–14.

Maurer M, Cheung DS, Theess W, Yang X, Dolton M, Guttman A, et al. Phase 2 randomized clinical trial of astegolimab in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;150:1517–24.

Silverberg JI, Bissonnette R, Kircik L, Murrell DF, Selfridge A, Liu K, et al. Efficacy and safety of etrasimod, a sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator, in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (ADVISE). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;2:18914.

Tyring SK, Rich P, Tada Y, Beeck S, Messina I, Liu J, et al. Risankizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Dermatol Ther. 2023;13:595–608.

Wollenberg A, Blauvelt A, Guttman-Yassky E, Worm M, Lynde C, Lacour J-P, et al. Tralokinumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from two 52-week, randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III trials (ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2)*. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:437–49.

Simpson EL, Gooderham M, Wollenberg A, Weidinger S, Armstrong A, Soung J, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab in combination with topical corticosteroids in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial (ADhere). JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:182.

Silverberg JI, Pinter A, Alavi A, Lynde C, Bouaziz J-D, Wollenberg A, et al. Nemolizumab is associated with a rapid improvement in atopic dermatitis signs and symptoms: subpopulation (EASI ≥ 16) analysis of randomized phase 2B study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:1562–8.

Gutermuth J, Pink AE, Worm M, Soldbro L, Bjerregård Øland C, Weidinger S. Tralokinumab plus topical corticosteroids in adults with severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to or intolerance of ciclosporin A: a placebo-controlled, randomized, phase III clinical trial (ECZTRA 7)*. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:440–52.

Simpson EL, Flohr C, Eichenfield LF, Bieber T, Sofen H, Taïeb A, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab (an anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibody) in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical corticosteroids: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase II trial (TREBLE). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:863-871.e11.

Wollenberg A, Howell MD, Guttman-Yassky E, Silverberg JI, Kell C, Ranade K, et al. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with tralokinumab, an anti–IL-13 mAb. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:135–41.

Gooderham MJ, Forman SB, Bissonnette R, Beebe JS, Zhang W, Banfield C, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral Janus kinase 1 inhibitor abrocitinib for patients with atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1371.

Silverberg JI, Pinter A, Pulka G, Poulin Y, Bouaziz J-D, Wollenberg A, et al. Phase 2B randomized study of nemolizumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and severe pruritus. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:173–82.

Ruzicka T, Hanifin JM, Furue M, Pulka G, Mlynarczyk I, Wollenberg A, et al. Anti–interleukin-31 receptor a antibody for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:826–35.

Zhao Y, Wu L, Lu Q, Gao X, Zhu X, Yao X, et al. The efficacy and safety of dupilumab in Chinese patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study*. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:633–41.

Kabashima K, Matsumura T, Komazaki H, Kawashima M. Nemolizumab improves patient-reported symptoms of atopic dermatitis with pruritus: post hoc analysis of a Japanese phase III randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Ther. 2023;13:997–1011.

Laquer V, Parra V, Lacour J-P, Takahashi H, Knorr J, Okragly AJ, et al. Interleukin-33 antibody failed to demonstrate benefit in a phase II, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:599–602.

Leshem YA, Bissonnette R, Paul C, Silverberg JI, Irvine AD, Paller AS, et al. Optimization of placebo use in clinical trials with systemic treatments for atopic dermatitis: an International Eczema Council survey-based position statement. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:807–15.

Evans K, Colloca L, Pecina M, Katz N. What can be done to control the placebo response in clinical trials? A narrative review. Contemp Clin Trials. 2021;107: 106503.

Lee HH, Patel KR, Rastogi S, Singam V, Vakharia PP, Chopra R, et al. Placebo responses in randomized controlled trials for systemic therapy in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:62–71.

Offidani A, Stingeni L, Neri I, Cipriani F, Chen Z, Rossi AB, et al. Dupilumab treatment induced similar improvements in signs, symptoms, and quality of life in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with baseline Eczema Area and Severity Index Score <24 or ≥24. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2022;2:157.

Chopra R, Vakharia PP, Simpson EL, Paller AS, Silverberg JI. Severity assessments used for inclusion criteria and baseline severity evaluation in atopic dermatitis clinical trials: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1890–9.

van Dorn A. COVID-19 and readjusting clinical trials. The Lancet. 2020;396:523–4.

Sathian B, Asim M, Banerjee I, Pizarro AB, Roy B, Van Teijlingen ER, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on clinical trials and clinical research: a systematic review. Nepal J Epidemiol. 2020;10:878–87.

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Writing support was provided by Michael Jonathan Riley, PhD, Fortis Pharma Consulting.

Funding

Funding for writing support, and for the journal’s Rapid Service Fee, was provided by Connect Biopharma.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors provided substantial contributions to the conception and design of the analyses and review manuscript and contributed to drafting the manuscript by critically reviewing it for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Jonathan I. Silverberg has acted as an advisor, speaker, or consultant for AbbVie Inc., AFYX, Arena, Asana, BiomX, Bluefin, Bodewell, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene Corporation, Connect Biopharma, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoth, Incyte, Kiniksa, Leo Pharma, Luna, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer, RAPT, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Sanofi. Researcher for Galderma. Selwyn Ho and Raúl Collazo are either current or former employees or shareholders of Connect Biopharma. Selwyn Ho is now an employee of Medigene AG, Planegg/Martinsried, Germany.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Silverberg, J.I., Ho, S. & Collazo, R. A Mini Review of the Impact of Baseline Disease Severity on Clinical Outcomes: Should We Compare Atopic Dermatitis Clinical Trials?. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 13, 3019–3029 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01052-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01052-5