Abstract

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a debilitating inflammatory disorder of the skin, characterized by a fluctuating natural history, a complex mechanism of action, and a significant burden on patients, including effect on quality of life, development of psychosocial disorders, and a range of comorbidities. Recent international guidelines recommend a therapeutic approach of first-line treatment with second generation H1-antihistamines and second-line treatment with the biologic omalizumab. Here, the salient aspects of CSU and current status of data for omalizumab for patients with CSU are reviewed, with a focus on mechanism of action, efficacy and real-world effectiveness (including patient outcomes, response, relapse, and remission), and safety (including consideration of the risk of anaphylaxis). The review also considers recent data on COVID-19, CSU, and omalizumab and presents our perspective on future needs. Overall, the data suggest that omalizumab is an effective and well-tolerated treatment for patients with CSU that provides benefits for a wide range of patients.

Plain Language Summary

Chronic spontaneous urticaria is a skin condition that causes raised red itchy bumps (known as hives) that appear on the skin on most days for 6 weeks or longer. The hives may be big or small, may be warm to touch, may come and go, and may affect a person’s quality of life. Omalizumab is a treatment for people living with chronic spontaneous urticaria that can stop the appearance of hives. This article summarizes all the information that we know about omalizumab for chronic spontaneous urticaria, such as how it works, how successful it is at improving hives, how long it takes to work, how it makes patients feel, and how safe it is. The information in this article shows that omalizumab is helpful for many people with chronic spontaneous urticaria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This review article presents a summary of the current evidence for the biologic omalizumab as a treatment for patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). |

Omalizumab is a beneficial treatment for appropriate patients with CSU as it improves both itch and wheals and quality of life, is supported by a well-established safety profile, and provides an opportunity for self-administration. |

Given this information is now easily accessible for clinicians, this review may improve treatment for patients with CSU. |

What is CSU?

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU, previously chronic idiopathic urticaria [CIU]) is a debilitating inflammatory disorder of the skin characterized by the occurrence of itchy wheals (hives) and/or angioedema for more than 6 weeks with no specific trigger [1] (and recently reviewed by Lang [2] and Kolkhir et al. [3]). CSU affects approximately 1–3% of individuals (lifetime prevalence) [4,5,6], is twice as prevalent in women than men [5, 6], more prevalent among patients aged 40–59 years than for other ages [5] (although prevalence is similar across childhood [7]), and there is limited evidence of racial or ethnic differences worldwide [8].

Accurate diagnosis of CSU is important, especially as wheals and angioedema also occur in patients with other diseases, and includes factors such as exclusion of differential diagnoses, identification of underlying causes, and identification of conditions that may modify disease activity [9]. Once diagnosed, clinicians find a variable natural history of the disease: CSU is a fluctuating condition marked by spontaneous remissions and relapses that requires frequent re-evaluation. For example, a small study (N = 72) found the duration of CSU ranged from 2 to 204 months, with 31% with relapsing/remitting disease [10], and a review of the literature found the proportion of patients achieving remission within 5 years ranged from 29% to 71% [11]. The presence or absence of angioedema also complicates CSU as angioedema is reported in approximately 50% of patients and leads to more severe and prolonged disease [10, 12, 13], and is an isolated finding in around 10% of cases [14]. In addition, prognosis in terms of duration and activity is predicted by certain factors: an observational study (N = 549) found worse prognosis is associated with multiple episodes of CSU, late-onset, concomitant chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU), and serum autoreactivity [15].

Given the complexity of CSU, many factors need to be considered before, during, and after treatment. Here, we review the salient aspects of CSU and highlight treatment with the primary (and only) biologic option, omalizumab.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of CSU is complicated and not completely understood. However, the driving process of mast cell activation has been elucidated and reviewed recently by Dobrican et al. [16], Hide and Kaplan [17], and Kaplan et al. [18], and briefly summarized herein. In most patients with CSU, mast cell activation and degranulation are driven by autoimmunity—either immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated type I autoimmunity (or autoallergy) or type IIb autoimmunity by IgG autoantibodies to IgE and/or the IgE receptor FcεRI on mast cells [19] (and reviewed by Hennino et al. [20] and Kolkhir et al. [21] and considered in recent articles [22, 23]). Mast cells may also be activated by other non-immunologic pathways including complement, stem cell factor, Toll-like receptors, Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor X2, and pathogen-associated and damage-associated molecular patterns; this aspect has been reviewed by Ansotegui et al. [24].

Regardless of the mechanism of mast cell degranulation, intracellular signaling triggers the release of multiple immunological mediators, including histamine, platelet activating factor, proteases, lipid metabolites, cytokines, and chemokines (tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin [IL]-1, IL-4, IL-6, IL-13, and platelet activating factor) [24, 25]. Vascular permeability is increased via the activation of endothelial cells, leading to wheals and angioedema [25]. Of note, the pathogenic role of infiltrating cells, such as neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, and monocytes, remains unclear, but has recently been considered by Giménez-Arnau et al. [26], and other mediators reviewed by Nettis et al. may also play a role [25]. For example, substance P action through the G protein-coupled receptor MRGPRX2 may release histamine in a subset of patients with CSU [27].

Patient Burden

CSU places a substantial burden on the patient, compromising quality of life (QoL) [8, 28] and interfering with activities of daily living including sleep, work productivity, and social functioning. For example, pruritus, painful and unsightly wheals, angioedema, and reduced sleep quality all contribute to diminished QoL [29,30,31]. In addition, sexual functioning of women may be impaired by CSU [32]. With regard to overall patient burden, the 2016 Global Burden of Disease Study found that the disability-adjusted life years rate for urticaria was 55.5/100,000 people in the general population, which ranked fourth among dermatological conditions, but the rate varied by geography, sex, and age [33]. Furthermore, the economic burden of CSU is substantial, and includes productivity loss because of absence from work and reduced work performance: in the ASSURE-CSU observational study (N = 673), mean (SD) overall work productivity loss was 43.6% (28.4%) in patients with more disease activity versus 11.9% (21.6%) in those with less disease activity, mostly because of presenteeism [34].

Of importance, patients with CSU are predisposed to develop psychosocial disorders. A systematic analysis of 114 studies found a prevalence estimate of 46% for psychosocial factors in patients with symptomatic CSU [35]. Patients with CSU experience higher rates of anxiety and depression relative to healthy controls [36, 37], which is linked to emotional distress [38] and increased impairment in QoL [39]. As an explanation, a mediation model proposed that anxiety and depression develop because itching associated with CSU leads to sleep disturbance [40], which is associated with risk of depression [41] and anxiety [42].

The burden on patients with CSU is also complicated by the association of CSU with a wide range of comorbidities. Comorbidities that are overrepresented among patients with CSU include atopic diseases such as allergic rhinitis and asthma, thyroid disease, rheumatic diseases, and inflammatory diseases [8], and there is a correlation between the frequency of comorbidities and the duration of urticaria [43]. In addition, patients with CSU (especially adult female patients and those with a positive family history) have an increased risk of autoimmune diseases, particularly vitiligo, pernicious anemia, and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis [44].

Overall, patients provide a very negative perspective of living with CSU. A non-interventional qualitative study found that patients with CSU commonly experienced anxiety, frustration, helplessness, and powerlessness, and reported feelings of loss of normalcy and identity, social stigmatization, shame, and distress [45].

Unmet Needs

Physicians often underestimate the true impact of CSU as it is fluctuating and non-life-threatening. However, the impact of CSU on health-related QoL is similar to that experienced by patients with other severe, disabling dermatological diseases such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis [46, 47] and patients with coronary artery disease [29]. Furthermore, CSU is often underdiagnosed. For example, a self-report survey (N = 1037) found that patients suffered from urticaria symptoms for around 3 years before diagnosis [48], and time to diagnosis is highly variable—even a small study (N = 25) found that time to diagnosis ranged from 1 week to 15 years [45]. Diagnosis is also complicated by the presence/absence of angioedema, which is often underreported [12]. Finally, CSU is often undertreated. For example, in an observational study, only 57.6% of patients diagnosed with H1-antihistamine-refractory CSU (N = 1539) were receiving pharmacological treatment [49], and a self-report survey (N = 1037) reported that 60.3% of patients were not currently receiving any treatment [48]. Maurer et al. [49] concluded that “the majority of CSU patients were undertreated, had uncontrolled urticaria and moderately or largely affected QoL [and there was a] need for improved patient care and adherence to the latest treatment guidelines.” However, although guidelines are available for the management of CSU, not all physicians are aware or follow the recommended path [50].

Guidelines for Treatment of CSU

An update to the international EAACI/GA2LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria was published in 2021 [1] (and recently reviewed by Zuberbier et al. [51]). The guidelines recommend that the therapeutic approach for CSU should aim for a complete response (complete control and normalization of QoL) and include elimination of possible underlying causes, avoidance of eliciting factors, tolerance induction, and the use of pharmacological treatment. The recommended first-line treatment is a second-generation H1-antihistamine. The recommended second-line treatment for patients who do not show benefit from H1-antihistamines is the biologic therapy omalizumab (300 mg every 4 weeks, independent of IgE levels) [1]. For patients with severe CSU, refractory to any dose of antihistamine or omalizumab, cyclosporin (3.5–5.0 mg/day) may be given.

As the only biologic approved and recommended for treatment of patients with CSU, a review of the current status of omalizumab data is warranted. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Omalizumab

Our review of omalizumab will focus on the mechanism of action, efficacy, and real-world effectiveness, including patient outcomes, response, relapse, and remission, and safety, for treatment of patients with CSU.

Of note, omalizumab is also beneficial (although not currently approved in the USA) for patients with CIndU, including cholinergic urticaria, cold urticaria, solar urticaria, heat urticaria, symptomatic dermographism, and delayed pressure urticaria [1, 52, 53]. This is likely because expression of FcεRI receptors on basophils and serum IgE levels are both elevated in patients with CindU, similar to CSU and independent of subtype [54].

Omalizumab is indicated for CSU “in adults and adolescents 12 years of age and older who remain symptomatic despite H1-antihistamine treatment” [55].

Mechanism of Action

Omalizumab is a humanized, recombinant, monoclonal anti-IgE antibody, originally developed for the treatment of allergic respiratory disorders such as asthma. The antibody binds to free IgE at the site of FcεRI binding [56], thus blocking free IgE from binding to FcεRI on mast cells (principally) and thereby preventing the immunological cascade. The potential of omalizumab to treat CSU associated with autoimmunity was proposed as early as 2005 [57], as the role of autoantibodies to FcεRI or IgE in CSU became clear [58]. The efficacy of omalizumab for auto-allergic CSU was confirmed in phase II efficacy studies in patients with CSU and IgE autoantibodies to thyroperoxidase [59].

The mechanism of action of omalizumab for CSU is not completely understood. In patients with CSU omalizumab not only reduces free IgE levels but also downregulates the expression of FcεRI on skin cells in the dermis of both lesional and non-lesional skin, and on basophils [60]. However, these pathways do not fully explain the clinical effects of omalizumab. Potential mechanisms of action that contribute to efficacy have been considered by Kaplan et al. [61] and include changes in mast cells, IgG and IgE autoantibodies, coagulation abnormalities, and a recent study found a possible link to vasoactive intestinal protein [62]. In addition, cross talk between mast cells and other immune cells creates complex systems in the microenvironment [63], which may further explain the action of omalizumab. Another clue to the mechanism of action is that patients with type IIb autoimmunity with IgG and IgM antibodies directed against IgE receptors on mast cells have more severe and prolonged CSU and a poorer response to omalizumab [64]. However, regardless of the intricacies of omalizumab action, the antibody is both efficacious and effective for many patients with CSU.

Efficacy and Effectiveness

The strength of evidence for omalizumab in CSU comes from the pivotal phase III studies ASTERIA I, ASTERIA II, and GLACIAL [65,66,67]. These phase III studies, as well as proof-of-concept and phase II studies, were reviewed by Giménez-Arnau [68]. All studies confirmed the efficacy of omalizumab versus placebo (by reduction of urticaria activity scores and itch severity score) in patients 12–75 years of age with H1-antihistamine-refractory moderate-severe CSU [68]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials (N = 1312) found that omalizumab significantly reduced itch and wheal scores compared with placebo, with the strongest reduction at 300 mg every 4 weeks, and significantly improved rates of complete response (relative risk 4.55) [69]. Of note, in patients from the phase III clinical trials, omalizumab was also able to increase the proportion of angioedema-free days [13].

Importantly, omalizumab is well tolerated and effective in a range of patients with CSU, including children [70, 71], adolescents [72, 73], and older people [74]. Moreover, despite higher CSU prevalence in female individuals, response to omalizumab is similar in both sexes although relapse is most common in male patients [75]. Omalizumab is also efficacious in patients in the East Asian population—the phase III POLARIS study found significant decreases in itch severity score for omalizumab versus placebo [76], and in patients with comorbid CIndU [77]. However, there is little or no information on omalizumab treatment in patients with CSU who are pregnant [78], have a malignancy, or are being treated with other systemic or biologic therapies for a comorbid condition [79].

Patient Outcomes

Omalizumab clinical trial results are supported by the phase IV SUNRISE study (N = 136), which found that by week 12 most patients on omalizumab achieved disease control (74.6%, by Urticaria Control Test score) and well-controlled disease (67.7%, by 7-day Urticaria Activity Score) [80]. Furthermore, omalizumab improves QoL, sleep, sexual function, anxiety, and work-related productivity in patients with CSU. For example, post hoc analyses of phase III clinical trials found that omalizumab improved Dermatology Life Quality Index versus placebo and provided initial and ongoing improvements in sleep [81,82,83], and a retrospective chart review found that omalizumab may play a role in enhancing sexual function [84]. In the phase IV EXTEND-CIU study, improvements following omalizumab initiation were observed at week 12 (first reported measurement) and were sustained for the study duration (48 weeks), and occurred in a range of patient-reported outcomes, including the perception of skin disease and control, sleep, work productivity, and anxiety [85, 86]. Overall, these findings highlight the ability of omalizumab to improve QoL outcomes in addition to urticarial lesions and pruritus.

Omalizumab also improves QoL in patients with CSU with angioedema. The X-ACT study (N = 91) found that by week 28, omalizumab was superior to placebo for improvement in Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire scores, and also improved angioedema-burdened days/week, median time to first recurrence of angioedema, and angioedema-specific quality of life [87]. However, to date, few studies have specifically assessed whether omalizumab is effective for patients with CSU with isolated angioedema, even though there is some evidence of effectiveness from case reports [79] and one small placebo-controlled trial [88]—this should be a focus of future work.

Patients completing a qualitative questionnaire describe that omalizumab treatment led to dramatic changes in multiple aspects of their QoL [89]. Quotes from the participants in response to the question “Please can you kindly tell us how your life has changed since starting your omalizumab treatment for urticaria/angio-oedema?” included “My life has become normal again… I think this treatment saved my life” and “It has given me my life back… for me this was a hugely beneficial and life-transforming treatment.”

Response, Relapse, and Remission

Response to omalizumab may vary and requires an individualized approach to maximize the potential for response and to prevent relapse. The time to response to omalizumab is an important consideration for clinicians: studies suggest that there are “early” and “late” responders to omalizumab, and many patients require multiple doses to achieve a response [90, 91]. For example, Kaplan et al. found that, although the median time to complete response was 8–10 weeks (300 mg omalizumab), some patients responded after the first injection, some patients achieved complete response before week 4, and some patients continued to achieve a complete response up to week 24 [90]. Indeed, about half of patients who were non-responders at week 12 had a response by week 24 [90]. The mechanism of action responsible for this differential response is unknown; however, early responders show a rapid decrease in IgE and basophil FcεRI receptor levels [90].

Therapeutic strategy may be guided by the initial response to omalizumab, e.g., non-responders and partial responders may require up-dosing and re-evaluation after 3 months, whereas good and complete responders may benefit from lower dosing after 3–6 months [92]. Metz et al. [93] reviewed real-world evidence for up-dosing of omalizumab and found that up-dosing (by increases in dose [to 450 mg then 600 mg] and/or frequency [to 2 weeks]) for refractory patients was safe and effective in up to 60% of patients. Up-dosing may be most valuable for patients with clinical factors such as angioedema, basophil activation, high body mass index, previously treated with cyclosporin A, older age, lower Urticaria Control Test score, or lower IgE levels [93, 94].

Although about 50% of patients with CSU enter long-term (> 4 years) remission following one to two courses of omalizumab [95], relapse may occur following discontinuation, especially in patients with high baseline Urticaria Activity Score or a slow decrease in symptoms [96]. However, a prospective, open-label study (N = 314) found that of the 18% of patients re-treated with omalizumab after relapse post-withdrawal, most (88%) regained symptomatic control, suggesting that re-treatment is as effective as initial treatment [97]. Of note, a retrospective study found that gradually extending the dosing interval in patients who responded to omalizumab may facilitate omalizumab discontinuation [98].

Predictors of Response

The most reliable predictor of response to omalizumab in patients with CSU or CIndU is IgE level [99,100,101,102,103,104]. Consistent across studies, non-responders to omalizumab (generally assessed at around 12–14 weeks after initiation) have baseline total IgE levels less than 20 IU/mL (around 40 IU/mL is often used as a cutoff point). IgE levels for partial response, complete response, and early response varied across studies, but were consistently seen with an IgE level of greater than around 70 IU/mL. However, please note that assessment of responders by IgE levels is duration-dependent as the proportion of patients who respond to omalizumab will increase over time [86, 90]. Using another approach, Ertas et al. [99] found that the best predictor of response was the ratio of week 4 IgE levels to baseline IgE levels: a ratio of 1.0 was significantly associated with non-response to omalizumab and a ratio of around 4.0 was significantly associated with a partial or complete response to omalizumab.

Other markers that may predict response to omalizumab include trough concentrations of serum omalizumab [105], expression of FcεRI [100] (especially on basophils [106]), eosinopenia [107], antinuclear antibodies [108], basophil CD203c activity [109], previous immunosuppressant treatment, D-dimer, and IL-31 [100, 101]. In a retrospective study of patients with CSU from a single center, a good response to omalizumab was associated with patients who were atopic (high eosinophils, basophils, and IgE) and a poor response was associated with comorbid psychiatric disease and thyroid antibodies [110]. Predictors of relapse following omalizumab withdrawal include high IgE levels [111], baseline Urticaria Activity Score [101], and early treatment response [96].

Safety

Omalizumab has a well-established safety profile, attained over 20 years across multiple indications and doses [112], and based on clinical trials and real-world studies (such as for asthma [113]). For CSU, a meta-analysis of 67 real-world studies reported an adverse event rate of 4% with omalizumab and a safety profile similar to that observed in clinical trials [114]. Long-term safety data collected over 9 years (N = 91) in a real-world setting found that prolonged omalizumab treatment did not increase the risk of side effects [115].

In the aforementioned 9-year real-world study, there were no reports of anaphylaxis following omalizumab administration in patients with asthma [115], which is similar to a single-center study of 22,000 doses of omalizumab [116]. Indeed, reports of anaphylaxis have been rare and inconsistent, and little information is available specifically for patients with CSU. In a comprehensive review of the literature and government databases in the USA, Canada, and Europe, Gulsen et al. found that the incidence of anaphylaxis following omalizumab ranged from 0% to 0.09%, which was lower than most other biologicals [117], and similar to clinical trials and initial post-marketing reports [55]. In an analysis of US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Events Reports, Li et al. found evidence of anaphylaxis following omalizumab, with incidence more life-threatening for patients with asthma versus urticaria [118]. Thus, although the boxed warning on the US omalizumab prescribing information provides awareness of anaphylaxis, we believe that the potential benefits outweigh the risk (although the risk should be considered for each individual and prescribing information should be adhered to, to ensure risk minimization). Others agree as self-administration of omalizumab is approved [55], and omalizumab is being considered as a preventative treatment for severe anaphylaxis, especially for people with food allergy [119].

COVID-19, CSU, and Omalizumab

Given the recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, it is relevant to consider any potential interactions between severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, CSU, and treatment with omalizumab. A global survey study found that the COVID-19 pandemic substantially impacted care of patients with CSU because of reduced referrals and clinic hours, and face-to-face consultations decreased by over 60% [120]. The study also found that, although the presence of CSU did not affect the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection, SARS-CoV-2 infection did lead to urticaria exacerbations in many patients [120].

Regarding treatment of allergic and type 2 inflammatory conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic, a European position paper recommended continued use of biologicals but noted that the potential effects of biologicals on the immune response in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection are unknown [121]. However, a recently published systematic review proposed that omalizumab may actually protect allergic patients against SARS-CoV-2 infection [122]. For treatment of CSU, the global survey study found that cyclosporine and systemic corticosteroids were used less during the pandemic, whereas use of antihistamines and omalizumab did not change [120]. Moreover, single-center studies have found no difference in SARS-CoV-2 positivity rate, or related pneumonia or hospitalizations for patients with CSU on omalizumab versus other treatments [123, 124]. Of note, a retrospective chart review study found that male patients, but not female patients, had increased urticaria activity during the COVID-19 pandemic and, as omalizumab treatment rates were similar, the authors concluded that omalizumab efficacy has decreased in male patients; however, this requires further investigation [125]. Importantly, patients on omalizumab were able to easily transition to home self-administration during the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling treatment to continue and fears regarding SARS-CoV-2 exposure to be lessened [126].

Of note, a single-center study found that 92% of patients with CSU currently on omalizumab did not show any exacerbation of urticaria following COVID-19 vaccination, and indeed acute adverse responses to the vaccine were decreased compared with patients on antihistamines [127] and anaphylactic reactions may have been prevented [128].

Clinicians’ Perspective

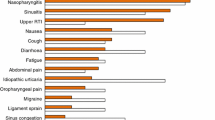

From our perspective, omalizumab is an effective and well-tolerated treatment for patients with CSU that provides benefits for a wide range of patients (see Fig. 1 for a summary). Moreover, omalizumab is approved for self-administration by appropriate patients with CSU and this has many practical and psychological benefits [129,130,131] and could contribute to improvements in QoL.

Although detailed guidelines are available for management of omalizumab [132], there are still unmet needs that should be addressed with future research. Areas that we believe could warrant more information to optimize use of omalizumab include the potential role of CSU pathogenesis in an individual (including autoallergy, anti-IgE antibodies, and angioedema) on the response to omalizumab; combination treatment (especially with other biologics [133]) for patients with comorbidities or slow responders; influence of pregnancy (by an initial analysis, pregnancy outcomes for patients with CSU treated with omalizumab were similar to patients with asthma where no increased risk was observed [134]); and the impact of race on access [135] and response.

In addition to practical implications, research and clinical experience with omalizumab has benefited the development process for new treatments, particularly for patients with CSU that is refractory to omalizumab. Research and development is constantly changing but has focused on two main avenues: (i) identification of biomarkers as predictors of response and as therapeutic targets (recently reviewed [136, 137]) and (ii) use of alternative biologics (recently reviewed [137,138,139,140]). The biologic furthest in development is the IL-4 and IL-13 antibody dupilumab. Although dupilumab reduced itch and hives in omalizumab-naïve patients (at 24 weeks), in patients refractory to omalizumab statistical significance was not reached [141], suggesting more research is needed. In addition, other potential future treatment options may have an inferior safety profile to that established for omalizumab over the past 20 years. Ultimately, new treatments for CSU are coming, but in the interim the optimization of omalizumab use is imperative.

Conclusion

Patients with CSU paint a negative picture of their lives and describe a debilitating disease with a fluctuating natural history that requires frequent re-evaluation and comes with a myriad of concomitant medical conditions. Here, we have provided a review of the current status of omalizumab—the primary and only biologic approved for treatment of CSU. In summary, omalizumab blocks free IgE and prevents the immune cascade (albeit via a complex mechanism of action), which translates to efficacy in clinical trials and effectiveness in the real world. A key feature is that the response to omalizumab varies by individual in terms of time to response, relapse after discontinuation, and remission after treatment. Importantly, we highlight a focus on patients as studies have investigated disease-specific patient outcomes, health-related QoL, patient perspectives, and the importance of self-administration. Finally, the consistent long-term safety profile of omalizumab across indications represents a positive benefit-to-risk ratio.

This review presents an opportunity to improve treatment for patients, as clinicians are now able to assess the body of evidence describing omalizumab as a therapy for patients with CSU.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Zuberbier T, Abdul Latiff AH, et al. The international EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2022;77(3):734–66.

Lang DM. Chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(9):824–31.

Kolkhir P, Gimenez-Arnau AM, Kulthanan K, Peter J, Metz M, Maurer M. Urticaria. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8(1):61.

Powell RJ, Leech SC, Till S, et al. BSACI guideline for the management of chronic urticaria and angioedema. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(3):547–65.

Wertenteil S, Strunk A, Garg A. Prevalence estimates for chronic urticaria in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):152–6.

Zuberbier T, Balke M, Worm M, Edenharter G, Maurer M. Epidemiology of urticaria: a representative cross-sectional population survey. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(8):869–73.

Balp MM, Weller K, Carboni V, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of chronic spontaneous urticaria in pediatric patients. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2018;29(6):630–6.

Sanchez-Borges M, Ansotegui IJ, Baiardini I, et al. The challenges of chronic urticaria part 1: epidemiology, immunopathogenesis, comorbidities, quality of life, and management. World Allergy Organ J. 2021;14(6):100533.

Metz M, Altrichter S, Buttgereit T, et al. The diagnostic workup in chronic spontaneous urticaria—what to test and why. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(6):2274–83.

Stepaniuk P, Kan M, Kanani A. Natural history, prognostic factors and patient perceived response to treatment in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2020;16:63.

Balp MM, Halliday AC, Severin T, et al. Clinical remission of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU): a targeted literature review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(1):15–27.

Sussman G, Abuzakouk M, Berard F, et al. Angioedema in chronic spontaneous urticaria is underdiagnosed and has a substantial impact: analyses from ASSURE-CSU. Allergy. 2018;73(8):1724–34.

Zazzali JL, Kaplan A, Maurer M, et al. Angioedema in the omalizumab chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria pivotal studies. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117(4):370–7 (e371).

Champion RH, Roberts SO, Carpenter RG, Roger J. Urticaria and angio-oedema. A review of 554 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81(8):588–97.

Curto-Barredo L, Archilla LR, Vives GR, Pujol RM, Gimenez-Arnau AM. Clinical features of chronic spontaneous urticaria that predict disease prognosis and refractoriness to standard treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(7):641–7.

Dobrican CT, Muntean IA, Pintea I, Petricau C, Deleanu DM, Filip GA. Immunological signature of chronic spontaneous urticaria (review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23(6):381.

Hide M, Kaplan AP. Concise update on the pathogenesis of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;150(6):1403–4.

Kaplan A, Lebwohl M, Gimenez-Arnau AM, Hide M, Armstrong AW, Maurer M. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: focus on pathophysiology to unlock treatment advances. Allergy. 2023;78(2):389–401.

Jang JH, Moon J, Yang EM, et al. Detection of serum IgG autoantibodies to FcεRIα by ELISA in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0273415.

Hennino A, Berard F, Guillot I, Saad N, Rozieres A, Nicolas JF. Pathophysiology of urticaria. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2006;30(1):3–11.

Kolkhir P, Munoz M, Asero R, et al. Autoimmune chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(6):1819–31.

Xiang YK, Kolkhir P, Scheffel J, et al. Most patients with autoimmune chronic spontaneous urticaria also have autoallergic urticaria, but not vice versa. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023:S2213-2198(2223)00184-00188.

Asero R, Ferrer M, Kocaturk E, Maurer M. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: the role and relevance of autoreactivity, autoimmunity, and autoallergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023:S2213–2198(2223)00226-X.

Ansotegui IJ, Bernstein JA, Canonica GW, et al. Insights into urticaria in pediatric and adult populations and its management with fexofenadine hydrochloride. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2022;18(1):41.

Nettis E, Foti C, Ambrifi M, et al. Urticaria: recommendations from the Italian Society of Allergology, Asthma and Clinical Immunology and the Italian Society of Allergological, Occupational and Environmental Dermatology. Clin Mol Allergy. 2020;18:8.

Giménez-Arnau AM, DeMontojoye L, Asero R, et al. The pathogenesis of chronic spontaneous urticaria: the role of infiltrating cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(6):2195–208.

Vena GA, Cassano N, Di Leo E, Calogiuri GF, Nettis E. Focus on the role of substance P in chronic urticaria. Clin Mol Allergy. 2018;16:24.

Goncalo M, Gimenez-Arnau A, Al-Ahmad M, et al. The global burden of chronic urticaria for the patient and society. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(2):226–36.

O’Donnell BF, Lawlor F, Simpson J, Morgan M, Greaves MW. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136(2):197–201.

Vietri J, Turner SJ, Tian H, Isherwood G, Balp MM, Gabriel S. Effect of chronic urticaria on US patients: analysis of the National Health and Wellness Survey. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(4):306–11.

Yun J, Katelaris CH, Weerasinghe A, Adikari DB, Ratnayake C. Impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life in Australian and Sri Lankan populations. Asia Pac Allergy. 2011;1(1):25–9.

Ertas R, Erol K, Hawro T, Yilmaz H, Maurer M. Sexual functioning is frequently and markedly impaired in female patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(3):1074–82.

Maxim E, Aksut C, Tsoi D, Dellavalle R. Global burden of urticaria: insights from the 2016 Global Burden of Disease Study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3):567–9.

Maurer M, Abuzakouk M, Berard F, et al. The burden of chronic spontaneous urticaria is substantial: real-world evidence from ASSURE-CSU. Allergy. 2017;72(12):2005–16.

Ben-Shoshan M, Blinderman I, Raz A. Psychosocial factors and chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review. Allergy. 2013;68(2):131–41.

Engin B, Uguz F, Yilmaz E, Ozdemir M, Mevlitoglu I. The levels of depression, anxiety and quality of life in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(1):36–40.

Tat TS. Higher levels of depression and anxiety in patients with chronic urticaria. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:115–20.

Staubach P, Dechene M, Metz M, et al. High prevalence of mental disorders and emotional distress in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91(5):557–61.

Staubach P, Eckhardt-Henn A, Dechene M, et al. Quality of life in patients with chronic urticaria is differentially impaired and determined by psychiatric comorbidity. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154(2):294–8.

Huang Y, Xiao Y, Jing D, et al. Association of chronic spontaneous urticaria with anxiety and depression in adolescents: a mediation analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:655802.

Li L, Wu C, Gan Y, Qu X, Lu Z. Insomnia and the risk of depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):375.

Johansson M, Jansson-Frojmark M, Norell-Clarke A, Linton S. Changes in insomnia as a risk factor for the incidence and persistence of anxiety and depression: a longitudinal community study. Sleep Sci Pract. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41606-020-00053-z.

Agondi RC, Argolo PN, Mousinho-Fernandes M, Gehlen B, Kalil J, Motta AA. Multiple comorbidities in patients with long-lasting chronic spontaneous urticaria. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98(1):93–6.

Kolkhir P, Borzova E, Grattan C, Asero R, Pogorelov D, Maurer M. Autoimmune comorbidity in chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16(12):1196–208.

Goldstein S, Eftekhari S, Mitchell L, et al. Perspectives on living with chronic spontaneous urticaria: from onset through diagnosis and disease management in the US. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99(12):1091–8.

Grob JJ, Revuz J, Ortonne JP, Auquier P, Lorette G. Comparative study of the impact of chronic urticaria, psoriasis and atopic dermatitis on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152(2):289–95.

Mendelson MH, Bernstein JA, Gabriel S, et al. Patient-reported impact of chronic urticaria compared with psoriasis in the United States. J Dermatol Treat. 2017;28(3):229–36.

Wagner N, Zink A, Hell K, et al. Patients with chronic urticaria remain largely undertreated: results from the DERMLINE online survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(3):1027–39.

Maurer M, Staubach P, Raap U, et al. H1-antihistamine-refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria: it’s worse than we thought—first results of the multicenter real-life AWARE study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47(5):684–92.

Kolkhir P, Pogorelov D, Darlenski R, et al. Management of chronic spontaneous urticaria: a worldwide perspective. World Allergy Organ J. 2018;11(1):14.

Zuberbier T, Bernstein JA, Maurer M. Chronic spontaneous urticaria guidelines: what is new? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;150(6):1249–55.

Maurer M, Metz M, Brehler R, et al. Omalizumab treatment in patients with chronic inducible urticaria: a systematic review of published evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(2):638–49.

Exposito-Serrano V, Curto-Barredo L, Aguilera Peiro P, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic inducible urticaria in 80 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(1):167–8.

Gimenez-Arnau AM, Ribas-Llaurado C, Mohammad-Porras N, Deza G, Pujol RM, Gimeno R. IgE and high-affinity IgE receptor in chronic inducible urticaria, pathogenic, and management relevance. Clin Transl Allergy. 2022;12(2): e12117.

Genentech. Xolair prescribing information. Genentech; 2021.

Presta LG, Lahr SJ, Shields RL, et al. Humanization of an antibody directed against IgE. J Immunol. 1993;151(5):2623–32.

Mankad VS, Burks AW. Omalizumab: other indications and unanswered questions. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2005;29(1):17–30.

Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria: pathogenesis and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2004;114(3):465–74.

Maurer M, Altrichter S, Bieber T, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic urticaria who exhibit IgE against thyroperoxidase. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2011;128(1):202–9 (e205).

Metz M, Staubach P, Bauer A, et al. Clinical efficacy of omalizumab in chronic spontaneous urticaria is associated with a reduction of FcepsilonRI-positive cells in the skin. Theranostics. 2017;7(5):1266–76.

Kaplan AP, Gimenez-Arnau AM, Saini SS. Mechanisms of action that contribute to efficacy of omalizumab in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy. 2017;72(4):519–33.

Ozaydin-Yavuz G, Yavuz IH, Inaloz HS, Boyvadoglu C. Omalizumab is not just an anti-immunoglobulin E. J Dermatol Treat. 2022;33:2858–61.

Zhou B, Li J, Liu R, Zhu L, Peng C. The role of crosstalk of immune cells in pathogenesis of chronic spontaneous urticaria. Front Immunol. 2022;13: 879754.

Gericke J, Metz M, Ohanyan T, et al. Serum autoreactivity predicts time to response to omalizumab therapy in chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(3):1059–61 (e1051).

Kaplan A, Ledford D, Ashby M, et al. Omalizumab in patients with symptomatic chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria despite standard combination therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(1):101–9.

Maurer M, Rosen K, Hsieh HJ, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(10):924–35.

Saini SS, Bindslev-Jensen C, Maurer M, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria who remain symptomatic on H1 antihistamines: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(3):925.

Giménez-Arnau AM. Omalizumab for treating chronic spontaneous urticaria: an expert review on efficacy and safety. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2017;17(3):375–85.

Zhao ZT, Ji CM, Yu WJ, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(6):1742–50 (e1744).

Dekkers C, Alizadeh Aghdam M, de Graaf M, et al. Safety and effectiveness of omalizumab for the treatment of chronic urticaria in pediatric patients. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021;32(4):720–6.

Ari A, Levy Y, Segal N, et al. Efficacy of omalizumab treatment for pediatric chronic spontaneous urticaria: a multi-center retrospective case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37(6):1051–4.

Ocak M, Soyer O, Buyuktiryaki B, Sekerel BE, Sahiner UM. Omalizumab treatment in adolescents with chronic spontaneous urticaria: efficacy and safety. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2020;48(4):368–73.

Song XT, Chen YD, Yu M, Liu B, Zhao ZT, Maurer M. Omalizumab in children and adolescents with chronic urticaria: a 16-week real-world study. Allergy. 2021;76(4):1271–3.

Martina E, Damiani G, Grieco T, Foti C, Pigatto PDM, Offidani A. It is never too late to treat chronic spontaneous urticaria with omalizumab: real-life data from a multicenter observational study focusing on elderly patients. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(2):e14841.

Sirufo MM, Bassino EM, De Pietro F, Ginaldi L, De Martinis M. Sex differences in the efficacy of omalizumab in the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2021;35:20587384211065870.

Hide M, Park HS, Igarashi A, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in Japanese and Korean patients with refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;87(1):70–8.

Skander D, Allenova A, Maurer M, Kolkhir P. Omalizumab is effective in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria plus multiple chronic inducible urticaria. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;53(2):91–3.

Gonzalez-Medina M, Curto-Barredo L, Labrador-Horrillo M, Gimenez-Arnau A. Omalizumab use during pregnancy for chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU): report of two cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(5):e245–6.

Turk M, Carneiro-Leao L, Kolkhir P, Bonnekoh H, Buttgereit T, Maurer M. How to treat patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria with omalizumab: questions and answers. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(1):113–24.

Berard F, Ferrier Le Bouedec MC, Bouillet L, et al. Omalizumab in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria nonresponsive to H1-antihistamine treatment: results of the phase IV open-label SUNRISE study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(1):56–66.

Finlay AY, Kaplan AP, Beck LA, et al. Omalizumab substantially improves dermatology-related quality of life in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(10):1715–21.

Gimenez-Arnau AM, Spector S, Antonova E, et al. Improvement of sleep in patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria treated with omalizumab: results of three randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Clin Transl Allergy. 2016;6:32.

Maurer M, Sofen H, Ortiz B, Kianifard F, Gabriel S, Bernstein JA. Positive impact of omalizumab on angioedema and quality of life in patients with refractory chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria: analyses according to the presence or absence of angioedema. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(6):1056–63.

Durmaz K, Ataseven A, Temiz SA, Isik B, Dursun R. Does omalizumab use in chronic spontaneous urticaria results in improvement in sexual functions? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21(10):4877–81.

Casale TB, Murphy TR, Holden M, Rajput Y, Yoo B, Bernstein JA. Impact of omalizumab on patient-reported outcomes in chronic idiopathic urticaria: results from a randomized study (XTEND-CIU). J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(7):2487–90 (e2481).

Casale TB, Win PH, Bernstein JA, et al. Omalizumab response in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria: insights from the XTEND-CIU study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(4):793–5.

Staubach P, Metz M, Chapman-Rothe N, et al. Effect of omalizumab on angioedema in H1-antihistamine-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria patients: results from X-ACT, a randomized controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71(8):1135–44.

Goswamy VP, Lee KE, McKernan EM, Fichtinger PS, Mathur SK, Viswanathan RK. Omalizumab for treatment of idiopathic angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129(5):605–11 (e601).

Porter E, Tierney E, Byrne B, et al. “It has given me my life back”: a qualitative study exploring the lived experience of patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria on omalizumab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47(11):2032–4.

Kaplan A, Ferrer M, Bernstein JA, et al. Timing and duration of omalizumab response in patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(2):474–81.

Syrigos N, Grapsa D, Zande M, Tziotou M, Syrigou E. Treatment response to omalizumab in patients with refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(4):417–22.

Gimenez Arnau AM, Valero Santiago A, Bartra Tomas J, et al. Therapeutic strategy according to differences in response to omalizumab in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2019;29(5):338–48.

Metz M, Vadasz Z, Kocaturk E, Gimenez-Arnau AM. Omalizumab updosing in chronic spontaneous urticaria: an overview of real-world evidence. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2020;59(1):38–45.

Bras R, Costa C, Limao R, Caldeira LE, Paulino M, Pedro E. Omalizumab in CSU: real-life experience in doses/intervals adjustments and treatment discontinuation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;S2213–2198(2223):00093–4.

Di Bona D, Nettis E, Bilancia M, et al. Duration of chronic spontaneous urticaria remission after omalizumab discontinuation: a long-term observational study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(6):2482–5 (e2482).

Ferrer M, Gimenez-Arnau A, Saldana D, et al. Predicting chronic spontaneous urticaria symptom return after omalizumab treatment discontinuation: exploratory analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(4):1191–7 (e1195).

Sussman G, Hebert J, Gulliver W, et al. Omalizumab re-treatment and step-up in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: OPTIMA trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(7):2372–8 (e2375).

Salman A, Aktas M, Apti SO. Remission of chronic spontaneous urticaria following omalizumab with gradually extended dosing intervals: real-life data. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62(3):398–402.

Ertas R, Ozyurt K, Atasoy M, Hawro T, Maurer M. The clinical response to omalizumab in chronic spontaneous urticaria patients is linked to and predicted by IgE levels and their change. Allergy. 2018;73(3):705–12.

Fok JS, Kolkhir P, Church MK, Maurer M. Predictors of treatment response in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy. 2021;76(10):2965–81.

Marzano AV, Genovese G, Casazza G, et al. Predictors of response to omalizumab and relapse in chronic spontaneous urticaria: a study of 470 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(5):918–24.

Straesser MD, Oliver E, Palacios T, et al. Serum IgE as an immunological marker to predict response to omalizumab treatment in symptomatic chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(4):1386–8 (e1381).

Weller K, Ohanyan T, Hawro T, et al. Total IgE levels are linked to the response of chronic spontaneous urticaria patients to omalizumab. Allergy. 2018;73(12):2406–8.

Yu M, Terhorst-Molawi D, Altrichter S, et al. Omalizumab in chronic inducible urticaria: a real-life study of efficacy, safety, predictors of treatment outcome and time to response. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51(5):730–4.

Ghazanfar MN, Bartko EA, Arildsen NS, et al. Omalizumab serum levels predict treatment outcomes in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: a three-month prospective study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2022;52(5):715–8.

Deza G, Bertolin-Colilla M, Sanchez S, et al. Basophil FcvarepsilonRI expression is linked to time to omalizumab response in chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(6):2313–6 (e2311).

Kolkhir P, Church MK, Altrichter S, et al. Eosinopenia, in chronic spontaneous urticaria, is associated with high disease activity, autoimmunity, and poor response to treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(1):318–25 (e315).

Ertas R, Hawro T, Altrichter S, et al. Antinuclear antibodies are common and linked to poor response to omalizumab treatment in patients with CSU. Allergy. 2020;75(2):468–70.

Palacios T, Stillman L, Borish L, Lawrence M. Lack of basophil CD203c-upregulating activity as an immunological marker to predict response to treatment with omalizumab in patients with symptomatic chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(3):529–30.

Cakmak ME. Comparison of the patients with chronic urticaria who responded and did not respond to omalizumab treatment: a single-center retrospective study. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2022;183(11):1209–15.

Ertas R, Ozyurt K, Ozlu E, et al. Increased IgE levels are linked to faster relapse in patients with omalizumab-discontinued chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(6):1749–51.

Lowe PJ, Georgiou P, Canvin J. Revision of omalizumab dosing table for dosing every 4 instead of 2 weeks for specific ranges of bodyweight and baseline IgE. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015;71(1):68–77.

Normansell R, Walker S, Milan SJ, Walters EH, Nair P. Omalizumab for asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1: CD003559.

Tharp MD, Bernstein JA, Kavati A, et al. Benefits and harms of omalizumab treatment in adolescent and adult patients with chronic idiopathic (spontaneous) urticaria: a meta-analysis of “real-world” evidence. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(1):29–38.

Di Bona D, Fiorino I, Taurino M, et al. Long-term “real-life” safety of omalizumab in patients with severe uncontrolled asthma: a nine-year study. Respir Med. 2017;130:55–60.

Harrison RG, MacRae M, Karsh J, Santucci S, Yang WH. Anaphylaxis and serum sickness in patients receiving omalizumab: reviewing the data in light of clinical experience. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(1):77–8.

Gulsen A, Wedi B, Jappe U. Hypersensitivity reactions to biologics (part I): allergy as an important differential diagnosis in complex immune-derived adverse events. Allergo J Int. 2020;29(4):97–125.

Li L, Wang Z, Cui L, Xu Y, Guan K, Zhao B. Anaphylactic risk related to omalizumab, benralizumab, reslizumab, mepolizumab, and dupilumab. Clin Transl Allergy. 2021;11(4): e12038.

Tanno LK, Demoly P. Biologicals for the prevention of anaphylaxis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;21(3):303–8.

Kocaturk E, Salman A, Cherrez-Ojeda I, et al. The global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the management and course of chronic urticaria. Allergy. 2021;76(3):816–30.

Klimek L, Pfaar O, Worm M, et al. Use of biologicals in allergic and type-2 inflammatory diseases during the current COVID-19 pandemic: position paper of Arzteverband Deutscher Allergologen (AeDA)(A), Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Allergologie und Klinische Immunologie (DGAKI)(B), Gesellschaft fur Padiatrische Allergologie und Umweltmedizin (GPA)(C), Osterreichische Gesellschaft fur Allergologie und Immunologie (OGAI)(D), Luxemburgische Gesellschaft fur Allergologie und Immunologie (LGAI)(E), Osterreichische Gesellschaft fur Pneumologie (OGP)(F) in co-operation with the German, Austrian, and Swiss ARIA groups(G), and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI)(H). Allergol Select. 2020;4:53–68.

Ghiglioni DG, Cozzi EL, Castagnoli R, et al. Omalizumab may protect allergic patients against COVID-19: a systematic review. World Allergy Organ J. 2023;16(2):100741.

Atayik E, Aytekin G. The course of COVID-19 in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria receiving omalizumab treatment. Rev Fr Allergol (2009). 2022;62(8):684–8.

Bostan E, Yalici-Armagan B, Gokoz O. Chronic urticaria may not be as innocent as we think: a rare case of acquired cutis laxa following chronic urticaria. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21(7):3154–6.

Kulu H, Atasoy M, Ozyurt K, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic affects male patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria more than female patients. Front Immunol. 2021;12:722406.

King C, Cox F, Sloan A, McCrea P, Edgar JD, Conlon N. Rapid transition to home omalizumab treatment for chronic spontaneous urticaria during the COVID-19 pandemic: a patient perspective. World Allergy Organ J. 2021;14(10): 100587.

Grieco T, Ambrosio L, Trovato F, et al. Effects of vaccination against COVID-19 in chronic spontaneous and inducible urticaria (CSU/CIU) patients: a monocentric study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(7):1822.

Smola A, Samadzadeh S, Muller L, et al. Omalizumab prevents anaphylactoid reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(11):e743–5.

Denman S, Ford K, Toolan J, et al. Home self-administration of omalizumab for chronic spontaneous urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(6):1405–7.

Menzella F, Ferrari E, Ferrucci SM, et al. Self-administration of omalizumab: why not? A literature review and expert opinion. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2021;21(4):499–507.

Murphy KR, Winders T, Smith B, Millette L, Chipps B. Identifying patients for self-administration of omalizumab. Adv Ther. 2023;40(1):19–24.

Agache I, Akdis CA, Akdis M, et al. EAACI Biologicals Guidelines—Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria in adults and in the paediatric population 12–17 years old. Allergy. 2022;77(1):17–38.

Koç Yildirim S, Erbağci E, Hapa A. Omalizumab treatment in combination with any other biologics: is it really a safe duo? Australas J Dermatol. 2023;64(2):229–33.

Namazy J, Scheuerle AE, Spain V, et al. Pregnancy and infant outcomes among pregnant women with chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) treated with omalizumab: a descriptive analysis from the EXPECT pregnancy registry. Presented virtually at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology | 26 February – March 1, 2021.

Mosnaim GS, Greenhawt M, Imas P, et al. Do regional geography and race influence management of chronic spontaneous urticaria? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;150(6):1260–4 (e1267).

Zhang Y, Zhang H, Du S, Yan S, Zeng J. Advanced biomarkers: therapeutic and diagnostic targets in urticaria. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2021;182(10):917–31.

Deza G, Ricketti PA, Gimenez-Arnau AM, Casale TB. Emerging biomarkers and therapeutic pipelines for chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(4):1108–17.

Greiner B, Nicks S, Adame M, McCracken J. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of chronic spontaneous urticaria: a literature review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2022;63(3):381–9.

Maurer M, Khan DA, Elieh Ali Komi D, Kaplan AP. Biologics for the use in chronic spontaneous urticaria: when and which. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(3):1067–78.

Metz M, Maurer M. Use of biologics in chronic spontaneous urticaria—beyond omalizumab therapy? Allergol Select. 2021;5:89–95.

Sanofi. Update on ongoing Dupixent® (dupilumab) chronic spontaneous urticaria phase 3 program. 2022. https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2022/2022-02-18-06-00-00-2387700. Accessed 16 May 2023.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by Janelle Keys, PhD, CMPP of Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by Genentech, Inc., a member of the Roche Group. Envision’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice.

Funding

Funding was provided by Genentech, Inc., a member of the Roche Group. Genentech provided funding for medical writing support and rapid publication fee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection and analysis was performed by all authors. All authors reviewed and commented on all drafts of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Jonathan A. Bernstein has served as a consultant and speaker bureau member for Genentech, Inc. Thomas B. Casale has served as a consultant and speaker bureau member for Genentech, Inc., and a consultant for Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Ana Maria Giménez-Arnau is or recently was a speaker and/or advisor for and/or has received research funding from Almirall, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Avene, Celldex, Escient Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, GSK, Instituto Carlos III- FEDER, Leo Pharma, Menarini, Novartis, Sanofi–Regeneron, Servier, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Uriach Pharma/Neucor. Michael Holden is an employee of Genentech, Inc., and a stockholder in Roche. Marcus Maurer has been a speaker and/or advisor for and/or has received research funding from Allakos, Amgen, Aralez, ArgenX, AstraZeneca, Celldex, Centogene, CSL Behring, Eli Lilly, FAES, Genentech, GI Innovation, GSK, Innate Pharma, Kyowa Kirin, Leo Pharma, Menarini, Moxie, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi/Regeneron, Third Harmonic Bio, UCB Pharma, and Uriach. Torsten Zuberbier has received institutional funding for research and/or honoraria for lectures and/or consulting from AbbVie, ALK, Almirall, Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer Health Care, Bencard, Berlin Chemie, FAES, HAL, Henkel, Kryolan, Leti, L’Oreal, Meda, Menarini, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Stallergenes Greer, Takeda, Teva, UCB Pharma, and Uriach, and is a member of ARIA/WHO, DGAKI, ECARF, GA2LEN, and WAO.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Casale, T.B., Gimenez-Arnau, A.M., Bernstein, J.A. et al. Omalizumab for Patients with Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Narrative Review of Current Status. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 13, 2573–2588 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01040-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01040-9