Abstract

Guselkumab is an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody that is approved for plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. We present a case of a 28-year-old female patient with acute onset of guttate psoriasis after a blistering sunburn. She had no personal or family history of psoriasis or chronic inflammatory skin disease. The guttate psoriasis was refractory to topical treatment. After the first dose of guselkumab (100 mg subcutaneous injection), the patient experienced near-clearance of her guttate psoriasis, with continued improvement and drug-free remission 8 months after cessation of treatment. Dermatologists could consider guselkumab as a treatment option for patients with guttate psoriasis. Future studies should examine the potential for guselkumab to induce drug-free remissions in guttate psoriasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Guselkumab is an anti-interleukin (IL)-23 monoclonal antibody that is approved for plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis but not guttate psoriasis |

To date, the research on the use of biologics in the treatment of guttate psoriasis has been limited |

This report highlights a case of guttate psoriasis induced by a sunburn that improved significantly after a single dose of guselkumab |

Dermatologists could consider guselkumab as a treatment option for patients with guttate psoriasis and further research should be conducted to examine the impact of IL-23 inhibitors on inducing of remission in guttate psoriasis |

Introduction

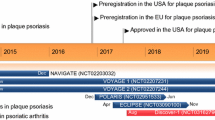

Guselkumab is a human immunoglobulin G (IgG) monoclonal antibody that binds with high specificity and affinity to p19 subunit of interleukin (IL)-23. Guselkumab blocks IL-23 signaling and subsequent release of additional pro-inflammatory cytokines by IL-23 receptor-expressing T cells [1]. This biologic medication was the first in its class to be approved for moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis as well as psoriatic arthritis. Guselkumab is currently being evaluated for the treatment of other psoriasis subtypes, such as palmoplantar and pustular psoriasis [2]. Here, we present a case of acute onset guttate psoriasis after a severe sunburn in an adult female patient, whose guttate psoriasis nearly cleared after her first dose of guselkumab and who has maintained skin remission 8 months after cessation of treatment.

Case Report

A 28-year-old female patient with no personal or family history of psoriasis or chronic inflammatory skin conditions presented at a telemedicine primary care visit with small, circular, pink raised papules of 1 month duration over her trunk and extremities. These lesions began developing 1 week after a severe sunburn that only involved her chest (Fig. 1). At the initial telemedicine visit, she was prescribed an unknown cream that did not improve the appearance, pruritis, or pain attributed to these lesions. She was then seen by a community dermatologist who performed a biopsy and confirmed the diagnosis of guttate psoriasis. Topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% was prescribed. However, she stated that this regimen was difficult to adhere to due to the numerous generalized spots. She also reported skin-thinning on a few areas of her thighs after 3 months of topical steroid use without improvement in her disease. On presentation to our dermatology clinic, she had numerous 2–4 mm well-demarcated papules and small plaques with scale on her trunk and upper and lower extremities, with a psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) of 6.7 (Figs. 2a, 3). The patient reported that the guttate lesions were worse on posterior thighs bilaterally. After discussing treatment options, the patient expressed interest in either phototherapy or biologic medication options. However, due to her high copay for phototherapy, she elected to participate in a clinical trial investigating the effect of guselkumab on guttate psoriasis (UCSF IRB approval protocol: 20-32273). At weeks 0, 4, 12, 20, 28, and 36, guselkumab 100 mg was administered. She achieved rapid clearance and remission including after cessation of guselkumab. After receiving the first 100 mg subcutaneous guselkumab injection, the patient noticed significant improvement after 1 month with a PASI of 0.4 (Figs. 2b, 3), and 8 months after last guselkumab injection, she showed complete remission with a PASI of 0 (Figs. 2c, 3). In addition, our patient’s physician global assessment (PGA) for psoriasis improved from moderate to severe, scored as 3 (with a maximum of 5), to almost clear/minimal, scored as 1, 1 month after her first guselkumab injection. After 8 months off therapy, PGA scored as 0 (clear).

Discussion

Guttate psoriasis is an uncommon form of psoriasis with a prevalence of approximately 0.6–1.2% in North America [3]. This distinct subtype of psoriasis is classically associated with streptococcal infection, including pharyngitis or perianal involvement. In addition, some cases of guttate psoriasis have been reported after infection with varicella and Pityrosporum folliculitis [2]. However, guttate lesions can also present in patients with no known recent infection. Guttate psoriasis typically occurs in a bimodal age distribution with peak onset at 20–30 years of age and 50–60 years of age, which aligns with our 28-year-old female patient’s case presentation [2]. Guttate psoriasis has been documented equally in occurrence in male and female genders [2]. Paradoxically, guttate psoriasis has also been reported after treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and certolizumab [2]. Notably, approximately 40% of patients with guttate psoriasis develop chronic plaque psoriasis over time; thus, studying whether early treatment of guttate psoriasis could help prevent the conversion to chronic plaque psoriasis is of high interest [2].

The Koebner phenomenon has been observed in plaque psoriasis, in which areas of wound healing and/or skin trauma, such as from excoriations or burns, trigger keratinocyte hyperproliferation [2]. Guttate psoriasis is not classically associated with the Koebner phenomenon. However, one case report published by Horner et al. in 2007 described the onset of guttate psoriasis in a 19-year-old female whose guttate psoriasis developed sparsely over her trunk but more prominently in and around a tattoo that was placed 7 months prior to a streptococcal infection [4]. Our patient experienced a severe sunburn on her chest and subsequently developed guttate psoriasis lesions beginning on her chest. She then developed guttate psoriasis on areas of her skin that were not sunburned, such as her bilateral upper and lower extremities.

Although the pathogenesis of plaque psoriasis has been well studied and documented, the pathogenesis of guttate psoriasis is less well understood. Both genetic and environmental factors play a role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Plaque psoriasis occurs via IL-17 cell mediated pathways, wherein IL-23 promotes Th17 stimulation, causing IL-17 and IL-22 release, leading to skin inflammation, hyperproliferation, and keratinization [5]. An important role for CD8 + IL17A/F + T cells has also been recognized in plaque psoriasis [6]. The Th17 pathway is also elevated in guttate psoriasis [7]. In addition, the HLA-C*06:02 allele is strongly associated with early onset of both plaque psoriasis and guttate psoriasis [2]. HLA B*13 and B*17 have also been strongly associated with guttate psoriasis [2].

Sunburn, in its mildest form, consists of a transient reddening or erythema of the exposed skin. With increasing intensity of ultraviolet B (UVB) exposure, sunburn is characterized by redness, pain, severe blistering, and skin necrosis. The inflammatory processes produce and secrete proinflammatory mediators including cytokines, chemokines, and prostaglandins produced mostly by keratinocytes; neutrophils then infiltrate into the irradiated site [8]. After skin injury from a sunburn, keratinocytes release cytokines including IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, colony-stimulating factors, TNF-alpha, and keratinocyte growth factors [8]. These inflammatory factors may have triggered an IL-23/IL-17 response in a genetically predisposed individual. Thus, we hypothesize that the release of these factors in response to sunburn may have played a role in our patient’s onset of guttate psoriasis.

In 2019, Hall et al. reported the complete resolution of guttate psoriasis plaques in one patient after a single administration of guselkumab [9]. Our patient presentation is the second case report of clearance of guttate psoriasis after administration of guselkumab. In 2013, Amarnani et al. published the first case report of the use of the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab for chronic, flaring guttate psoriasis [10]. In this case report, a 56-year-old woman with a 40-year history of guttate psoriasis flares associated with stress and infection as well as chronic asthma was treated with ustekinumab. Ultimately, her guttate psoriasis completely resolved. In 2017, Brummer et al. presented a case series of six patients with recalcitrant guttate psoriasis successfully treated with ustekinumab [11]. The duration of guttate psoriasis ranged in this case series ranged from 3 months to 36 months, and the number of ustekinumab injections until psoriasis clearance ranged from one to three injections [11]. Our patient had guttate psoriasis for approximately 4 months before treatment with guselkumab and had near clearance in her psoriasis after one injection. At 8 months of follow-up and six doses of guselkumab, complete clearance of disease was seen in our patient. Finally, one case series study performed by Flora and Frew et al. in 2022 reported treatment and remission of acute-onset guttate psoriasis with risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor [12]. In this case series, four patients aged 21, 24, 37, and 42 years had initial PASI scores of 12, 10.2, 8.8, and 11.4, respectively [12]. All four patients achieved complete clearance of psoriasis (PASI-100) from between 4 weeks and 12 weeks. In addition, all four patients maintained PASI-100 after follow up ranging from 12 months to 24 months [12]. These data suggest promising evidence that IL-23 inhibitors such as ustekinumab, guselkumab, and risankizumab may be used in the future for treatment of guttate psoriasis, though clinical trials with larger patient cohorts and a control group are needed to improve the power and significance of these studies.

Conclusion

This report highlights a case of guttate psoriasis induced by a sunburn that improved significantly after a single dose of guselkumab. Clinicians could consider guselkumab as a treatment option for patients with guttate psoriasis that does not improve with topicals or other therapies.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Sofen H, Smith S, Matheson RT, et al. Guselkumab (an IL-23–specific mAb) demonstrates clinical and molecular response in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(4):1032–40.

Terui T, Kobayashi S, Okubo Y, Murakami M, Hirose K, Kubo H. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti–interleukin 23 monoclonal antibody, for palmoplantar pustulosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(3):309.

Saleh D, Tanner L. Saleh D, Tanner LS. Guttate Psoriasis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Horner KL, Chien AJ, Edenholm M, Hornung RL. Winnie the pooh and psoriasis too: an isomorphic response of guttate psoriasis in a tattoo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24(5):E70–2.

Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(6):1475.

Teunissen MBM, Yeremenko NG, Baeten DLP, et al. The IL-17A-producing CD8 + T-Cell population in psoriatic lesional skin comprises mucosa-associated invariant T cells and conventional T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(12):2898–907.

Ruiz-Romeu E, Ferran M, Sagristà M, et al. Streptococcus pyogenes-induced cutaneous lymphocyte antigen-positive T cell-dependent epidermal cell activation triggers TH17 responses in patients with guttate psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(2):491-499.e6.

Schwarz A, Bhardwaj R, Aragane Y, et al. Ultraviolet-B-induced apoptosis of keratinocytes: evidence for partial involvement of tumor necrosis factor-α in the formation of sunburn cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104(6):922–7.

Hall S, Haidari W, Feldman SR. Resolution of guttate psoriasis plaques after one-time administration of guselkumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(8):822–3.

Amarnani A, Rosenthal KS, Mercado JM, Brodell RT. Concurrent treatment of chronic psoriasis and asthma with ustekinumab. J Dermatol Treat. 2014;25(1):63–6.

Brummer GC, Hawkes JE, Duffin KC. Ustekinumab-induced remission of recalcitrant guttate psoriasis: a case series. JAAD Case Reports. 2017;3(5):432–5.

Flora A, Frew JW. A case series of early biologic therapy in guttate psoriasis: targeting resident memory T cell activity as a potential novel therapeutic modality. JAAD Case Reports. 2022;24:82–7.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient in this case report.

Medical writing/editorial assistance

The authors did not receive any medical writing support or editorial assistance for this paper.

Funding

The patient described here participated in an investigator-initiated clinical trial funded by Janssen Pharmaceuticals and the Rapid service fee was waived by the publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. All named authors contributed to the final paper as follows: Conceptualization: Wilson Liao; Formal analysis and investigation: Erin Bartholomew, Bo-Young Chung, Mitchell Davis, Samuel Yeroushalmi, Mimi Chung, Marwa Hakimi, Tina Bhutani, and Wilson Liao; Writing the manuscript: Erin Bartholomew, Bo Young Chung, and Wilson Liao; Supervision: Wilson Liao.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Informed consent was obtained under UCSF IRB approval protocol: 20-32273.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Wilson Liao, MD has received research funding from Abbvie, Amgen, Janssen, Leo, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, and TRex Bio. Tina Bhutani is a principal investigator for trials sponsored by Abbvie, Castle, CorEvitas, Dermavant, Galderma, Mindera, and Pfizer. She has received research grant funding from Novartis and Regeneron. She has been an advisor for Abbvie, Arcutis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Leo, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun, and UCB. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bartholomew, E., Chung, BY., Davis, M. et al. Rapid Remission of Sunburn-Induced Guttate Psoriasis with Guselkumab. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 13, 2473–2478 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01013-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-01013-y