Abstract

Introduction

Pediatric atopic dermatitis (AD) leads to a considerable reduction in quality of life for patients and their families. Therapeutic options for pediatric patients with moderate-to-severe disease are limited and treatment is challenging. As little is understood about physician perceptions of pediatric AD in countries with emerging healthcare, we conducted a questionnaire-based study to identify treatment patterns and gaps.

Methods

Physicians treating children (aged 6–11 years) and adolescents (aged 12–17 years) with AD in 11 emerging economy countries were interviewed regarding their beliefs and behaviors relating to the disease. Physicians gave an initial assessment of patient disease severity and control, which was then compared with patient records and pre-specified criteria to assess concordance and discordance between physician perception and recorded patient presentation.

Results

A total of 574 physicians completed the study, with an assessment of 1719 patients. Only 51% of patients whose disease criteria matched ‘severe disease’ to pre-specified criteria and SCORing Atopic Dermatitis scores (SCORAD) were also initially identified by physicians as having severe disease. Patients with moderate-to-severe disease experienced flares for an average of 263 days in the preceding year. Ninety and 74% of patients experienced chronic flares and unpredictable flares, respectively. Control of flares could only be achieved within 7 days in 14% (n = 153) of patients. Most physicians listed elimination of skin symptoms as their primary treatment goal, and for moderate and severe cases, 59% and 33% of physicians reported that they were able to achieve this respectively. Nearly 24% and 40% of physicians were slightly dissatisfied with the treatment options for moderate disease and severe disease and severe disease, respectively.

Conclusions

AD severity of children (aged 6–11 years) and adolescents (aged 12–17 years) appears to be underestimated by physicians in emerging economy countries. Practical, easy-to-use, and validated objective measures for assessment of disease severity and control, as well as effective use of novel therapies, are essential to ensure that patients are appropriately managed.

Plain Language Summary

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common childhood disease that occurs in up to 30% of individuals under 18 years of age. Although most forms are mild, more severe disease forms of AD including symptoms such as pruritus, xerosis, lichenification, and excoriation of the skin can cause significant problems, such as lack of sleep, lack of productivity, poor self-image, and mental health disorders among patients. It also places a burden on patients’ families, which affects home, school, and work life. In children with moderate-to-severe disease, treatment options are limited especially since doctors may not be keen to prescribe high-dose treatments to children such as potent and super-potent topical corticoid steroids and progress to systemic therapies. Relatively little is understood about how doctors determine whether the disease is mild, moderate, or severe and what they consider to be the best treatment options for patients. Therefore, we conducted a series of interviews with doctors in 11 countries with emerging healthcare to better understand their beliefs and behaviors about treating childhood AD. Our results indicated that doctors tended to underestimate the severity of a patient’s disease. Additionally, 59% of doctors felt that they were able to successfully eliminate itching and skin syndrome frequently (that is, in 70% or more of their patients) in patients with moderate disease and 33% of doctors for their patients with severe disease. These results suggest that there are many unmet needs in the treatment of children and adolescents with AD in emerging economies, whose treatment could be further optimized. Improving how doctors measure the severity of a patient’s disease should help them select the most appropriate and effective treatments for their patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Children and adolescents with atopic dermatitis have a high burden of disease and many unmet needs |

Little is known about how physicians in emerging economies perceive disease severity, disease control, and treatment outcomes in relation to their pediatric and adolescent patients with atopic dermatitis |

What did the study ask? |

Physicians were interviewed about disease severity, control, and treatment in their children and adolescents with atopic dermatitis; responses were compared with patient report forms supplied by the physicians |

What has been learned from the study? |

Physicians tended to underestimate disease severity and control in children and adolescents atopic dermatitis |

The use of objective, validated disease severity scores in atopic dermatitis is an important guide for disease assessment and management |

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory systemic disease that typically presents in the early years of life, with a childhood prevalence of approximately 10–30% [1]. Although most cases resolve during childhood, some cases persist through adolescence and into adulthood [2]. It has been estimated that the disease persists through adolescence in 10–20% of children with AD, with prevalence estimates ranging from 0.9 to 21.1% [3].

AD in childhood and adolescence is associated with considerable morbidity and comorbid conditions such as allergies, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, leading to a poor quality of life (QoL) for the patient, their caregivers, and family. Intense itch and sleep disturbance are debilitating aspects of AD, reported in 90% of infants and 69% of adolescents [1, 4]. AD persisting into adolescence typically presents with more severe disease and atopic comorbidities [5]. Patients with moderate-to-severe disease suffer a considerable reduction in QoL, with > 50% of patients reporting their disease to have a “very” or “extremely” large effect [6]. Notably, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation are significantly higher in patients with skin diseases, including AD [7, 8]. Although there is a perception that AD reduces in severity or disappears with age, this is not the case for a minority of cases (7%, late resolving AD) [2]. As a disease with a significant burden and high prevalence in childhood, effective treatment, and understanding of how best to approach treatment in these patients, is essential.

Childhood and adolescent disease presentations often require differing approaches to treatment compared to adult patients. For topical treatments, the burden is on caregivers of younger children who are responsible for topical application [9]. Adolescents also have lower adherence to prescribed skincare regimes [1, 10]. For more severe AD, many systemic therapies are only available for off-label use in patients < 18 years of age, including treatments that have been approved for use in adults, such as cyclosporine [11]. Therefore, improving these unmet treatment needs is of particular importance for children and adolescents. This situation is changing with the recent approval of biologics in the younger age groups of ≥ 6 years [13].

Inconsistencies among healthcare professionals when recommending therapies for pediatric patients may lead to suboptimal treatment [9]. One of the biggest barriers to effective shared decision-making between patients and healthcare professionals in AD is a lack of continuity in treating physicians [14], implying variation among treatment recommended by physicians. A considerable discordance has been reported between physicians’ perception of the success of prescription medicine and the perceptions of both pediatric [15] and adult [16] patients, who are less convinced of treatment effectiveness.

Hence, to improve treatment outcomes for pediatric patients with AD, it is important to understand the perception of patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals about the course of disease and management in real-world settings. This study aimed to characterize the attitudes, beliefs, and behavior of healthcare professionals toward the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD in children (aged 6–11 years) and adolescents (aged 12–17 years). Here, we present the results of the quantitative portion of the physician interviews.

Methods

Design and Study Setting

This was a two-stage study collecting patient record forms (PRFs) and conducting qualitative interviews and a quantitative (online or computer-aided personal interview) questionnaire. The participants were healthcare professionals responsible for the treatment of pediatric patients with moderate-to-severe AD in Argentina, Brazil, China, Colombia, Israel, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia (KSA), Taiwan, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Ethics committee approval was not required as this study is Market Research and as defined in Section 1 of the EphMRA Code of Conduct, Market Research does not require ethics approval.

Participating Physicians

Physicians were recruited through an independent online database of validated physicians who had consented to participate in research. All participants were practicing dermatologists, allergologists, immunologists, or pediatricians treating children or adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD per month (n ≥ 2 to > 20 patients). Physicians were also required to be responsible for initiating or modifying systemic treatments in patients with moderate-to-severe AD, aware of at least one biologic therapy, not actively avoiding prescription of biologic therapy, not employed by or affiliated with a pharmaceutical company other than for clinical trials, and willing to complete PRFs and all study questionnaires. For physicians in China, participants were required to be chief or vice-chief doctors working in a Tier 3 hospital with a capacity of > 500 patients. At least 50% of the participant sample were required to be active prescribers of biologic therapy for any disease in the prior 6 months.

All recruitment and research were conducted in accordance with the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association code of conduct [17]. Physician anonymity was maintained throughout the study, including to the study sponsor.

Interview Questionnaires and Data Collection

The initial, qualitative stage of the study aimed to identify and inform the content of the quantitative questionnaire. In each country, 12 physicians were interviewed in detail about the local treatment of moderate-to-severe pediatric AD. Responses were collated by The Research Partnership and used to develop a quantitative questionnaire suitable to enable data aggregation and comparison across all countries.

The quantitative questionnaire was designed to be completed in 60 min to establish physician caseload, attitudes, and perceived behaviors. The questionnaire was developed in English, translated into the local language, and proofread to ensure consistency and accuracy. Questionnaires for UAE, KSA, and Israel were in English. The questionnaires were programmed to ensure that questions could not be missed and were delivered and completed online. Except for KSA and the UAE, computer-aided personal interviews were conducted, where a laptop was provided containing the questionnaire and the interviewer was present, but did not interact with the participant during the interview. Each physician was asked to provide three appropriate PRFs, one each for children with severe AD, adolescents with severe AD, and adolescents with moderate AD, if possible.

During the questionnaire, physicians were asked for an initial, spontaneous assessment of disease severity in patients for whom a PRF had been supplied according to the pre-specified patient’s inclusion criteria; however, the assessment was based solely on the physician’s clinical opinion. The PRFs of these patients were then compared against a list of pre-defined criteria to assess concordance and discordance between physician perception and recorded patient presentation (as defined by the study sponsor, listed in Table 1). An initial physician assessment followed by an assessment of the PRF against pre-defined criteria was also requested for disease control (Table 1).

Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

A final sample of at least 30 physicians participating per country was planned. The participant sample was structured based on the advice of the sponsor’s local affiliates to best reflect the most relevant specialists in each country. With a sample size of 30–75 participants per country, 95% confidence level, and assuming a sample proportion of 50% within a normally distributed data set, the margin of error was determined to be < 20% at physician level and < 10% at PRF level.

Statistical testing, as summary statistics, was conducted via data tables in Excel: z-tests were used for distributions and t-tests for mean scores. There was no pre-specified hypothesis for this study.

Results

Participants and Patient Record Forms

A total of 574 physicians across 11 countries completed the quantitative stage of the study, supplying 1719 PRFs (Table 2). The patient demographics are shown in Table 3. The majority of patients had a family history of AD and a mean of 2.4 comorbidities with allergic rhinitis, dust allergy, and asthma being the most common.

Physician Perception of Disease Severity

Physicians in all assessed countries stated they primarily used the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) criteria, except for physicians in KSA and Taiwan (body surface area), Turkey (Hanifin and Rajka), and the UAE (Dermatology Quality of Life Index).

With the exception of Mexico and Turkey, physicians in every country underestimated the severity of AD during their initial, spontaneous assessment of their overall patient caseload when this was compared with the pre-specified definitions of severe and moderate disease (Fig. 1). Differences were also observed between physicians assessing patients as moderate or severe based on the pre-specified definitions and severity assessed by SCORAD. For children, there was an overall concordance of 47% between patients considered severe according to the provided definition and being assessed as severe using SCORAD; for adolescent patients, this concordance was 44% for severe and 54% for moderate disease.

Proportion (%) of patients adjudged to have moderate or severe disease. Physicians were asked to rate the disease severity of the patients aged 6–17 they had treated in the prior month, initially by their own assessment (left-hand bars of each pair) and then (for the same patients) using a provided definition of moderate or severe disease (right-hand bars of each pair)

For children identified as having the severe disease by both pre-specified definition and SCORAD (the combination of which implies that more indicators of severe disease were present), fewer than half of patients (~ 48%) were also assessed as having severe disease according to the physicians’ assessment. For adolescent patients categorized as severe by both pre-specified definition and SCORAD, 53% of patients were also considered to have severe disease by physician assessment. Moderate disease in adolescence was identified by the pre-specified definition and SCORAD was better matched, with 94% of patients considered to have the moderate disease by physicians.

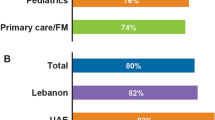

The severity of the disease was underestimated in 78% of children and 68% of adolescents with severe disease and overestimated in 19% of adolescents with the moderate disease by the physician (Fig. 2).

Physician Perception of Disease Control

Physicians considered comparable numbers of patients (42%) as uncontrolled by initial assessment versus the pre-specified definition (47%). Physicians estimated, without being supplied with a definition of flare, that the average number of days those patients had experienced flares in the preceding 12 months was 263. Days with flares were similar across age and severity (children with severe disease: 260 days; adolescent with severe disease: 271 days; adolescent with moderate disease: 260 days). Chronic flares were experienced by 90% of patients and nearly half experienced persistent symptoms (children with severe disease: 50%; adolescent with severe disease: 47%; adolescent with moderate disease: 43%); few patients had no signs or symptoms between flares (9%, 8%, and 12%, respectively). Unpredictable flares were experienced by 74% of patients (76% of children with severe disease, 74% of adolescents with severe disease, and 71% of adolescents with moderate disease).

Physicians indicated that few symptoms of flares could be controlled within 7 days of initiating treatment. For children with severe disease, physicians indicated that flares were controlled within 7 days for 11% of patients. This was 7% for adolescents with severe disease and 9% for adolescents with moderate disease. Mean treatment times to successfully treat the most recent flare were reported as 17, 22, and 20 days for severe children, severe adolescents, and moderate adolescents, respectively (Fig. 3).

Likelihood of Disease Remission

Only 19% and 18% of physicians, respectively, agreed that children and adolescents with severe disease would be disease-free by 18 years of age. More physicians agreed that their patients with moderate (35% and 26% for children and adolescents, respectively) and mild (56% and 42%, respectively) disease were expected to fully recover. Only in the UAE did the majority of physicians agree that their patients with severe disease (77% for both children and adolescents) would outgrow their disease by 18 years of age.

Burden of Disease

From the PRF analysis, AD was perceived to have an “extreme” impact on patient quality of life for 48% of children with severe disease, 58% of adolescents with severe disease, and 50% of adolescents with moderate disease. The greatest effect was perceived to be on emotional impact (78%) and social and sporting activities (77%), with less impact on learning (59%) and practical considerations, such as clothing choice (57%).

Treatment Goals and Satisfaction

Most physicians listed complete elimination of itching and skin symptoms as their primary treatment goal (56% for moderate disease and 45% for severe disease), followed by prevention of progression or relapse (25% and 27%, respectively) and reducing hospitalization (9% for severe disease) (Fig. 4a). For elimination of itching and skin syndrome, 59% and 33% of physicians reported that they were able to achieve this frequently (that is, in 70% or more of patients) in moderate and severe cases, respectively (Fig. 4b); 24% and 40% of physicians were slightly dissatisfied (or worse) with treatment options for moderate disease and severe disease, respectively.

a Treatment goal most frequently ranked first by physicians treating moderate and severe pediatric atopic dermatitis. b The extent to which physicians consider they are able to achieve complete elimination of itching and skin symptoms (among physicians considering this in their top three treatment goals)

The most commonly reported therapies used in the prior 12 months were emollients (in 92–93% of patients) followed by potent or super-potent topical corticosteroids (in 83% of children with severe disease, 91% adolescents with severe disease, and 87% of adolescents with moderate disease). Oral corticosteroids were used in 44%, 58%, and 48% of children, adolescents with severe disease, and adolescents with moderate disease, respectively, and biologics in 8%, 9%, and 7%, respectively. Physicians in all countries (except Turkey, for which biologics were not provided as an option) indicated that biologics had been prescribed (at any point) in patients under the age of 18 with AD. In severe disease, corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressants were used in 26% of children and 35% of adolescents. Adjuvant prescription antihistamines were prescribed to 77%–78% of patients. Physicians reported being “moderately” to “very concerned” about corticosteroid and immunosuppressant exposure in 68% and 73% of their patients, respectively.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in AD that compares the difference between physician perception of patient disease status with objective assessments in key emerging economies. Younger patients are of particular interest because of the limited available therapeutic options compared with adults and because of the potential reticence among physicians to prescribe more potent therapies [15]. Relatively little is understood about patient and healthcare professional perceptions of AD in emerging countries (based on the International Monetary Fund’s definition [18]), where the burden of AD is expected to increase with urbanization as these economies develop [19]. Therefore, we focused on 11 diverse nations across Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East to gain a greater understanding of AD in these countries. Notably, despite the cultural and economic differences in the countries sampled, this study confirmed that many aspects of clinical practice and patient and disease experience are consistent.

The responses from this study highlighted discordance between physicians’ perception of a patient’s disease and the recorded disease status as well as between treatment decisions and outcomes. When comparing an initial assessment of severity (based on the physician’s opinion, without comparison against a standard definition or severity scale) against the provided definition, the vast majority of patients with severe AD were assessed as having the less severe disease. Although no criteria were set, by definition, for the physician’s assessment of severity, 7 of 11 countries included in the study recommend using SCORAD as the standard assessment of AD. It could be speculated that physicians’ perceptions would (or should) be based on the tools with which they are most familiar and/or are recommended to use in their clinic. However, even where recommended, validated tools are rarely used in typical clinical practice [20], and there may be less awareness of tools than expected. A study of US physicians found the poor awareness of standard measures “surprising,” with > 30% of dermatologists unaware of SCORAD [21]. The need for effective, validated, and reliable measures have been extensively highlighted by the Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) initiative, which has recommended appropriate measures for use in both clinical trials [22] and daily clinical practice [23]. Notably, the HOME recommendation for the use of patient-oriented eczema measure (POEM) or patient-oriented (PO)-SCORAD in clinical practice is based on the instruments being “easy to use” and “free” and able to improve the “patient experience” [23].

The average number of days with a flare for patients in this study was estimated at 263 days per year. This is more than double the estimate of Zuberier et al. [24], who reported patients spending 1 in 3 days in flare, and is a significant and potentially unnecessary burden for patients whose quality of life is affected by the active disease. Furthermore, fewer than 10% of patients (including those with no flares) with the most severe disease in this study showed no signs or symptoms between flares and ~ 75% experienced unpredictable flares. Because there is no standard definition of flare, either in standard clinical practice or among trials [25, 26], it is difficult to assess how the physicians interviewed for the current study have defined flare. According to their assessments, the mean treatment time for flares ranged from 17 to 22 days, depending upon the severity, implying that “successful” treatment of flares did not result in complete resolution of flare symptoms. This further indicates an inclination to accept a baseline level on ongoing disease among physicians and the lack of an aggressive treatment strategy to completely resolve symptoms. Moreover, because control is defined as disease activity between flares, the low level of the uncontrolled disease reported in this study could be interpreted as a consequence of the relatively few flare-free days lived by patients and/or that the definition of control used in this study did not capture the true extent of the disease burden.

Few physicians agreed that their patients would be disease-free by 18 years of age, while more physicians agreed that their patients with moderate and mild disease were expected to fully recover. Childhood skin diseases are often considered relatively benign, manageable, and self-resolving [5], and although the effects of AD on quality of life are poorly understood [27, 28], they are reported to be comparable to serious chronic diseases such as cystic fibrosis [29]. Overestimates of remission may contribute to physicians actively avoiding the use of systemic therapies in younger patients, leaving them under-treated and at greater risk of comorbidities. A survey of healthcare providers in Finland indicated that 90% were confident about treating AD in children under 1 year of age, despite 56% of this population selecting inadequate therapies [30] likely to contribute to under-treatment.

Current management of childhood and adolescent AD relies on a limited number of treatments with varying effectiveness [11, 31]. Our study reported low satisfaction with available treatments. New therapeutic options are needed in this population, and those that have recently become available [13, 31] need to be effectively integrated into treatment regimens for patients with moderate-to-severe disease.

Two-thirds of physicians reported being unable to frequently completely eliminate itching and skin symptoms in patients with severe AD, and a similar number were unable to frequently prevent disease progression. This failure to reach goals is despite the use of potent or super-potent topical corticosteroids in the vast majority of patients and a high proportion of systemic corticosteroid and immunosuppressant usage. It is well established that treatment adherence is challenging in this population. Children rely on caregivers to administer systemic and apply topical therapies [9], with the challenge of low adherence [29] exacerbated by parents’ well-documented concerns about corticosteroid use [32]. Adherence among adolescents, who have greater responsibility for self-management, is also low [1, 10]. Low adherence results in poorer resolution, despite high levels of prescription of disease-modifying therapies. There may also be reticence among physicians about prescribing potent or systemic therapies for long periods, especially in patients who do not consider having severe disease. There is a growing understanding that personalized treatment strategies to achieve patient-led goals should be used to guide therapeutic choices that result in effective outcomes [22, 27, 30]. A US survey of physicians and patients under 15 years of age (or their parents) indicated that there was 95% agreement between the two groups in their perception of disease severity [15]. If similar concordance is seen in emerging nations, this would indicate that both patients and physicians underestimate severity, which, in turn, might contribute to under-treatment and/or disappointment with prescribed therapies.

The use of biologic therapy was low in this cohort, which might be due to low availability, high cost, or lack of confidence and experience in biologic use in an adolescent population. Notably, biologics were not licensed for use in the countries at the time of the study; yet the proportion of patients receiving off-label biologics was 8%. These factors combined are likely to contribute to the failure to achieve desired goals. Outcomes from real-world clinical studies support the need for greater use of more effective therapies, including biologics [33] and personalized treatment approaches to achieve the most beneficial outcomes [34]. Clear treatment models that can be followed by all specialties involved in the care of children and adolescents with AD and the need for aggressive treatment strategies, such as the AD Yardstick step-up approach recommending phototherapy, dupilumab, and systematic immunosuppressant therapy for the treatment of patients showing signs and symptoms of poorly or inadequately controlled AD despite an aggressive course of topical prescription therapy for ≥ 3 weeks, have been cited as necessary to lessen disease burden in AD [20].

There are limitations to the current study. Fundamental to the questionnaire- and interview-based research is the selection of participants, who may or may not be representative of local practice. Additionally, spontaneous responses to questions about disease and patients rely on memory and provide no standard baseline on what constitutes severity, control, or flares. Because this research was quantitative, no qualitative follow-up questions were included to assess why particular beliefs were held or responses provided; as such, we can only speculate on the reasons for the apparent discordance between some initial responses and the PRF data. No age-matched, healthy volunteer data are included to compare or provide a baseline for comorbidities or quality of life assessments, and this physician-focused study did not collect patient data to assess concordance between physician and patient perception. Nevertheless, the large number of physicians included and general concordance of responses across countries indicate robust data that need to be considered to improve outcomes for children and adolescents with AD.

Conclusion

In conclusion, children and adolescents’ AD severity appears to be underestimated in emerging economy countries. The significant burden of disease is likely exacerbated by under-treatment and subsequent poorer outcomes for patients, including the associated psychosocial burden suffered by younger patients, their caregivers, and family. Data presented here, as well as surveys from the US and Europe [21, 30], demonstrate that the development and everyday use of practical, easy-to-use, and validated objective measures for a holistic assessment of disease severity and control are essential to ensure that patients are appropriately and effectively treated. Combined with timely guidance on the use of new treatments as they become available, accurate assessment of disease and symptom control in a patient-guided approach will improve AD management and disease control.

References

Ricci G, Bellini F, Dondi A, Patrizi A, Pession A. Atopic dermatitis in adolescence. Dermatol Rep. 2012;4(1):1.

Paternoster L, Savenije OEM, Heron J, Evans DM, Vonk JM, Brunekreef B, et al. Identification of atopic dermatitis subgroups in children from 2 longitudinal birth cohorts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(3):964–71.

Odhiambo JA, Williams HC, Clayton TO, Robertson CF, Asher MI. Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(6):1251-8.e23.

Marciniak J, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Quality of life of parents of children with atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(6):711–4.

Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Boguniewicz M, Sher L, Gooderham MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(1):44–56.

Sánchez-Pérez J, Daudén-Tello E, Mora AM, Lara SN. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life in Spanish children and adults: the PSEDA study. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104(1):44–52.

Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, Lien L, Poot F, Jemec GBE, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(4):984–91.

Yu SH, Silverberg JI. Association between atopic dermatitis and depression in US adults. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(12):3183–6.

Koster ES, Philbert D, Wagelaar KR, Galle S, Bouvy ML. Optimizing pharmaceutical care for pediatric patients with dermatitis: perspectives of parents and pharmacy staff. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(3):711–8.

Kosse RC, Bouvy ML, Daanen M, de Vries TW, Koster ES. Adolescents’ perspectives on atopic dermatitis treatment-experiences, preferences, and beliefs. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(7):824–7.

Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for the treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):850–78.

Dupixent Prescribing Information. 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761055s020lbl.pdf.

Sanofi: Dupixent® (dupilumab) approved by European Commission for adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. 2019. https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2019/2019-08-06-07-00-00.

van der Kraaij GE, Vermeulen FM, Smeets PMG, Smets EMA, Spuls PI. The current extent of and need for shared decision making in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis in the Netherlands: an online survey study amongst patients and physicians. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(11):2574–83.

Paller AS, McAlister RO, Doyle JJ, Jackson A. Perceptions of physicians and pediatric patients about atopic dermatitis, its impact, and its treatment. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2002;41(5):323–32.

McAlister RO, Tofte SJ, Doyle JJ, Jackson A, Hanifin JM. Patient and physician perspectives vary on atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2002;69(6):461–6.

European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association. EphMRA Code of Conduct. 2019. https://www.ephmra.org/media/2811/ephmra-2019-code-of-conduct-doc-f.pdf.

World Economic Outlook. Global Manufacturing Downturn, Rising Trade Barriers. 2019. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2019/10/01/world-economic-outlook-october-2019.

Xu F, Yan S, Li F, Cai M, Chai W, Wu M, et al. Prevalence of childhood atopic dermatitis: an urban and rural community-based study in Shanghai, China. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):174.

Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Guttman-Yassky E, Ong PY, Silverberg J, Farrar JR. Atopic dermatitis yardstick: Practical recommendations for an evolving therapeutic landscape. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(1):10-22.e2.

Wei W, Anderson P, Gadkari A, Blackburn S, Moon R, Piercy J, et al. Discordance between physician- and patient-reported disease severity in adults with atopic dermatitis: a US cross-sectional survey. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(6):825–35.

Schmitt J, Spuls PI, Thomas KS, Simpson E, Furue M, Deckert S, et al. The Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement to assess clinical signs of atopic eczema in trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):800–7.

Leshem YA, Chalmers JR, Apfelbacher C, Furue M, Gerbens LAA, Prinsen CAC, et al. Measuring atopic eczema symptoms in clinical practice: the first consensus statement from the Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema in clinical practice initiative. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(5):1181–6.

Zuberbier T, Orlow SJ, Paller AS, Taïeb A, Allen R, Hernanz-Hermosa JM, et al. Patient perspectives on the management of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(1):226–32.

Langan SM, Schmitt J, Williams HC, Smith S, Thomas KS. How are eczema “flares” defined? A systematic review and recommendation for future studies. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(3):548–56.

Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, Cooper KD, Silverman RA, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(6):1218–33.

Koszorú K, Borza J, Gulácsi L, Sárdy M. Quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2019;104(3):174–7.

Silverberg JI, Margolis DJ, Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Grayson MH, Ong PY, et al. Validation of five patient-reported outcomes for atopic dermatitis severity in adults. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(1):104–11.

Yang EJ, Sekhon S, Sanchez IM, Beck KM, Bhutani T. Recent developments in atopic dermatitis. Pediatrics. 2018;142:4.

Yrjänä JMS, Bloigu R, Kulmala P. Parental confusion may result when primary health care professionals show heterogeneity in their knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding infant nutrition, food allergy, and atopic dermatitis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2018;46(4):326–33.

FDA approves Dupixent® (dupilumab) for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adolescents. 2019. http://www.news.sanofi.us/2019-03-11-FDA-approves-Dupixent-R-dupilumab-for-moderate-to-severe-atopic-dermatitis-in-adolescents. Accessed Oct 2020.

Simpson EL, Bruin-Weller M, Flohr C, Ardern-Jones MR, Barbarot S, Deleuran M, et al. When does atopic dermatitis warrant systemic therapy? Recommendations from an expert panel of the International Eczema Council. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(4):623–33.

Faiz S, Giovannelli J, Podevin C, Jachiet M, Bouaziz JD, Reguiai Z, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in a real-life French multicenter adult cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):143–51.

Sicras-Mainar A, Navarro-Artieda R, Armario-Hita JC. Severe Atopic Dermatitis In Spain: A Real-Life Observational Study. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019;15:1393–401.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and Rapid Service Fee was funded by Sanofi. The market research was conducted by Research Partnership, London, UK, funded by Sanofi.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing assistance for the development of this manuscript was provided by Daniel Clarke, PhD, at Syneos Health, and funded by Sanofi and editorial support was provided by Geetika Kainthla, MSc, of Sanofi.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Mark Tang, Mohammed Fatani, Simmi Wiggins, and Jorge Maspero have contributed substantially to the concept and design of the study, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and drafting of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Mark Tang has received speaking honoraria and participated in advisory boards for LEO Pharma, Menarini, Sanofi, Regeneron, Bioderma, Hyphens, and GSK; Mohammed Fatani has received research grants from AbbVie and speaking honorarium and participated in advisory boards for Sanofi, AbbVie, and Eli Lilly; Simmi Wiggins is an employee of and may own stocks/stock options in Sanofi; Jorge Maspero has received speaker fees or research grants from or participated in advisory boards for Uriach, Menarini, Inmunotek, AstraZeneca, GSK, MSD, Sanofi, Novartis, and AbbVie.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Ethics committee approval was not required as this study is Market Research and as defined in Section 1 of the EphMRA Code of Conduct, Market Research does not require ethics approval.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, M.B.Y., Fatani, M., Wiggins, S. et al. Physician Perception of Disease Severity and Treatment Outcomes for Children and Adolescents with Atopic Dermatitis in Emerging Economies. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 12, 999–1013 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00708-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00708-y