Abstract

Plaque psoriasis is an immune-mediated inflammatory skin disease associated with the dysregulation of cytokines, especially those involved in the interleukin (IL)-23/IL-17 pathways. In recent years, there has been growing interest in developing biologic therapies that target these pathways. However, inhibition of the cytokines of the IL-23/IL-17 pathways may increase patients’ risk of developing fungal infections, particularly oral candidiasis. Therefore, it is important that dermatology practitioners can effectively diagnose and treat oral candidiasis. In this review, we examine the role of the IL-23/IL-17 pathways in antifungal host defense, and provide a practical guide to the diagnosis and treatment of oral candidiasis in patients with psoriasis. Overall, while treatment with anti-IL-17 medications leads to an increased incidence of oral candidiasis in patients with psoriasis, these cases are typically mild or moderate in severity and can be managed with standard antifungal therapy without discontinuing treatment for psoriasis. If applicable, patients with psoriasis should also be advised to practice good oral hygiene and manage or control co-existing diabetes, and should be provided with information on smoking cessation to prevent oral candidiasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

The interleukin-23/interleukin-17 pathways, which are central to the pathogenesis of plaque psoriasis, are also involved in host defense against oral candidiasis. |

Given the increased risk of oral candidiasis in patients with psoriasis receiving anti-interleukin-17 therapies, dermatologists should be attentive to clinical signs of oral candidiasis and aware of how to manage cases appropriately. |

This review provides a practical guide to the diagnosis and treatment of oral candidiasis in patients with psoriasis being treated with anti-interleukin-17 biological therapies. |

What was learned from this study? |

Oral candidiasis in patients with psoriasis is typically mild to moderate in severity. In our clinical experience, cases can be managed with standard antifungal treatment without discontinuing biologic psoriasis therapies. |

To prevent recurrence of oral candidiasis, patients should be advised to practice good oral hygiene and be provided with information on smoking cessation, if applicable. |

Introduction

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated inflammatory skin disease associated with dysregulation of inflammatory cytokines that affects approximately 41 million people worldwide [1, 2]. The cytokines of the interleukin (IL)-23/IL-17 pathways have been identified as key mediators of psoriasis pathogenesis [3]. Subsequently, there has been growing interest in developing biologic therapies that target these pathways [4, 5]. However, as a result of the roles of IL-17 and IL-23 in antifungal host defense at the oral mucosa, targeting these cytokines may increase patients’ risk of developing fungal infections, particularly oral candidiasis [6].

Here, we provide an overview of the role of the IL-23/IL-17 pathways in antifungal host defense, as well as a practical guide to the treatment of oral candidiasis in patients with psoriatic disease.

This review article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors

The IL-23/IL-17 Pathways and Immunity

Overview and Role in Psoriasis

The main producers of IL-17, along with T cytotoxic 17 (Tc17) cells, are T-helper (Th)17 cells—a subset of Th cells that differentiate from naïve CD4+ T cells upon exposure to proinflammatory cytokines [7, 8]. The IL-17 family consists of six ligands (IL-17A to IL-17F) that bind to receptors (IL-17R) expressed ubiquitously throughout the body [9,10,11,12,13]. IL-17A and IL-17F share the closest homology and can exist as homodimers or heterodimers [5]. While not required for the induction of the Th17 and Tc17 lineages, IL-23 is required for the stabilization and proliferation of these cells [7, 8].

Although the etiology of psoriasis is not fully understood, genetic and environmental factors appear to contribute to atypical activation of the immune system, resulting in disease [14, 15]. The cytokines IL-17A and IL-17F in particular have been identified as key upregulated proinflammatory cytokines in psoriatic lesions; they are thought to recruit immune cells to psoriatic skin, stimulating the hyperproliferation of keratinocytes [16, 17].

Role in Host Defense Against Candida

One of the major roles of the IL-23/IL-17 pathways is host defense against fungal infections [18]. The most common species involved, Candida albicans, is usually commensal; however, upon conversion to a hyphal state it can cause mucocutaneous candidiasis [19].

The key role of IL-17 signaling in host defense against Candida is supported by observations from patients with primary immunodeficiencies leading to defects in the Th17 pathway, who present with a form of chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC) termed CMC disease (CMCD) [20]. These patients are prone to recurrent oral and esophageal candidiasis, suggesting a pivotal role of IL-17 in defense against candidiasis in the mucosa of the upper digestive tract [20]. However, these patients are not prone to systemic or vulvovaginal candidiasis, leading to an emerging consensus that the IL-23/IL-17 pathways are not essential to immune defense against these infections [19, 21,22,23]. These patients also rarely display any other severe diseases [24].

According to the current model of host defense against oral candidiasis, conversion of C. albicans to a hyphal state results in the activation of immune cells in response to damage [25]. These cells then produce proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-23, inducing the proliferation of Th17 cells and the release of IL-17A and IL-17F as well as IL-22. Neutrophils are then recruited to the infection site by these cytokines, inducing the secretion of antifungal proteins (Fig. 1) [19, 26]. Therefore, through the inhibition of IL-17 or its receptors, anti-IL-17 medications prescribed for psoriasis can increase the risk of oral candidiasis through inhibition of these Th17 cell-mediated antifungal pathways.

Simplified model of host defense against oral candidiasis. Colonization of the oral mucosal epithelium by Candida results in the activation of macrophages and DCs, either directly or indirectly, via alarmins such as IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-36, which are released in response to tissue damage by the peptide candidalysin. This then triggers the expression and secretion of IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-23, which induce the differentiation and proliferation of Th17 cells from naïve CD4+ T cells. These Th17 cells produce the cytokines IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22, which recruit neutrophils to the site of infection and act on epithelial cells to induce the release of antifungal β-defensins. Through the inhibition of IL-17 or its receptors, anti-IL-17 medications prescribed for psoriasis can increase the risk of oral candidiasis through inhibition of Th17 cell-mediated antifungal pathways. DC dendritic cells, IL interleukin, R receptor, Th17 T-helper cell type 17

Epidemiology of Candida Colonization and Infection in Psoriasis

There is some evidence of increased Candida colonization of the oral cavity in patients with psoriasis versus those without psoriasis. In a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of nine studies, statistically higher rates of Candida colonization of mucosal membranes were observed in patients with psoriasis [27]. For example, rates were reported as 69% versus 44% for those without psoriasis in a study conducted in Jordan [28], and 47.2% versus 19.5% in a study conducted in Germany [29]. This trend was consistent with another study where patients with psoriasis receiving systemic treatment were excluded (20.0% versus 2.8%) [30]. The reason for this association is unclear. Notably, there was considerable heterogeneity in these studies, and most measured the presence of Candida colonization rather than true candidiasis [27].

Risk of Candidiasis in Patients Receiving Biologic Treatments for Psoriasis

In recent years, several monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-17 (e.g., brodalumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab), IL-23 (e.g., guselkumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab), and IL-12/23 (e.g., ustekinumab) have been approved for treatment of psoriatic disease [4].

A systematic review of previous trials of anti-IL-17 medications in psoriatic disease found that overall incidence of candidiasis was increased in patients treated with anti-IL-17 medications versus placebo (1.7–4.0% versus 0.3%, respectively) [31]. The majority of Candida infections were oral and not vulvovaginal. Moreover, most oral candidiasis cases were mild to moderate in severity [31]. There was also no increase in the risk of esophageal or systemic candidiasis, further supported by a systematic review of all IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors [31, 32].

Bimekizumab, an anti-IL-17 medication recently authorized in Europe for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis [33], inhibits IL-17F in addition to IL-17A [34]. Dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F has demonstrated superior levels of skin clearance compared with targeting IL-17A alone with secukinumab in a head-to-head in patients with plaque psoriasis [35]. As expected, as a result of the roles of both cytokines in antifungal host defense, dual neutralization was also associated with an increased incidence of mild to moderate oral candidiasis as compared with previously approved anti-IL-17 medications [36,37,38].

Despite both bimekizumab and brodalumab inhibiting the activity of IL-17A and IL-17F, differences have been observed in the rates of oral candidiasis. This could be a consequence of the mechanistic differences between these two biologics. One hypothesis is that, as brodalumab inhibits IL-17R, it blocks the function of all additional IL-17 cytokines, including IL-17E which may indirectly suppress Th17 responses [13]. Furthermore, if IL-17R is not fully blocked at the end of a dosing cycle, it is possible that residual IL-17 may confer host protection against Candida. However, further research into this topic is needed.

Anti-IL-23 biologics do not seem to increase the risk of Candida infections as much as anti-IL-17 biologics [39]. This may be because anti-IL-23s do not block IL-23-independent sources of IL-17, such as IL-17 produced by innate lymphoid cells [3, 39]. However, IL-23-independent sources of IL-17 are increasingly thought to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, which may explain the higher efficacy of some anti-IL-17 medications compared with IL-23 blockers axial spondyloarthritis and joint outcomes in psoriatic arthritis [40, 41].

Diagnosis and Treatment of Oral Candidiasis

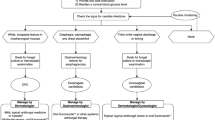

Given the increased risk of oral candidiasis in patients with psoriasis treated with anti-IL-17 medications, it is important that dermatology practitioners can effectively diagnose and treat these infections. On the basis of a review of the literature and clinical experience, we propose the diagnosis and treatment algorithm for oral candidiasis shown in Fig. 2.

Algorithm for the diagnosis and management of oral candidiasis in patients with plaque psoriasis. aIn the case that administration of anti-IL-17 treatment falls on the same day in which the antifungal treatment for oral candidiasis is initiated, administration of anti-IL-17 can be postponed for 3–4 days to prioritize resolution of oral candidiasis

Clinical Presentations of Oral Candidiasis

Pseudomembranous Candidiasis

Pseudomembranous candidiasis (or “thrush”) is sometimes referred to as the classic presentation of candidiasis [42], and in our clinical experience is most commonly identified in patients with psoriasis receiving anti-IL-17 treatment. It is characterized by the presence of white, curd-like plaques that can be dislodged with gentle scraping, revealing underlying erosions of the oral mucosa (Fig. 3A) [43,44,45,46]. Patients are often asymptomatic; however, pain, a burning sensation, and in some cases a metallic taste may be present [46].

Clinical presentations of oral candidiasis. A Pseudomembranous candidiasis in a male patient receiving anti-IL-17A treatment for plaque psoriasis; this patient was also a smoker. Patient image was provided courtesy of Dr Gisondi. B Acute erythematous candidiasis of the tongue. Patient image was borrowed from the Mount Sinai collection

Erythematous Candidiasis

Erythematous candidiasis is the most common form of oral candidiasis [46]. There are four subtypes: acute erythematous candidiasis, chronic erythematous candidiasis, angular cheilitis, and median rhomboid glossitis.

Acute erythematous candidiasis presents as painful reddened lesions which occur throughout the oral cavity (Fig. 3B) [43,44,45,46]. In chronic erythematous candidiasis (or “denture stomatitis”), these lesions are localized to the fitting surface of dentures [43,44,45,46]. Angular cheilitis, most commonly seen in elderly patients with over-closure of the jaw, is characterized by reddened lesions at the corner of the mouth [43,44,45,46]. Finally, the least common subtype, median rhomboid glossitis, presents as a rhomboid-shaped area of atrophy and erythema on the midline posterior tongue dorsum [43, 45].

Chronic Hyperplastic Candidiasis

Chronic hyperplastic candidiasis is a rare form of oral candidiasis that presents as a thickened white plaque, most frequently at the commissural region of the mouth or the dorsum of the tongue. However, unlike in pseudomembranous candidiasis, this plaque cannot be removed by gentle scraping [42,43,44,45,46,47]. Plaques may be smooth and isolated (homogeneous) or nodular and speckled (heterogeneous) [45,46,47].

Risk Factors for Oral Candidiasis

The presence of predisposing factors, other than treatment with anti-IL-17 medications, can also inform diagnosis of oral candidiasis. These factors are divided into two categories: local factors that affect the local oral environment and microflora and systemic factors that affect the host’s immune status (for a full list see Table 1) [43].

Local Predisposing Risk Factors

One of the most common local risk factors is the use of dentures, which can create a favorable environment for Candida growth, especially if denture hygiene is poor [43, 48, 49]. It is estimated that up to 75% of adults who wear dentures have some form of erythematous candidiasis, although most are unaware of it [48].

Another common local predisposing factor is the use of steroid inhalers, which may cause alterations in the oral microflora and is commonly associated with pseudomembranous candidiasis [42, 43, 49, 50]. Incidence of oral candidiasis in users of steroid inhalers generally ranges from 1% to 7% in the literature [51].

Patients who use or smoke tobacco have significantly increased oral Candida carriage levels and rates of oral candidiasis [49, 52]. Hyperplastic candidiasis is almost exclusively found in patients who smoke [47]; however, the exact underlying mechanism remains unclear [52].

Systemic Predisposing Risk Factors

The best-characterized systemic predisposing factors for oral candidiasis are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and chemotherapy and radiotherapy for cancer [49, 53, 54]. Antibiotic use is also associated with oral candidiasis, particularly acute erythematous candidiasis (commonly referred to as “antibiotic sore mouth”) [43,44,45,46, 49].

Other major systemic predisposing factors for oral candidiasis are extremes of age; both elderly patients and infants have increased risk of oral candidiasis due to lower levels of protective salivary defenses [43]. Elderly patients may also have a loss of vertical dimension of occlusion, increasing the risk of developing angular cheilitis [43].

Diabetes and poor glycemic control have also been associated with oral candidiasis; patients with poorly controlled diabetes often exhibit reduced salivary pH and increased salivary glucose levels, facilitating Candida proliferation [49, 55].

Confirmation of Diagnosis

Oral candidiasis is typically diagnosed according to the presence of clinical signs and symptoms in patients with predisposing factors [45, 56]. If there are diagnostic doubts, diagnosis can be confirmed via microbiologic examination [45, 49]. Fresh samples from the oral tissues can be taken and examined microscopically using 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) [45]. This method is useful for distinguishing erythematous manifestations of oral candidiasis from conditions with similar presentations, such as thermal traumatic lesions, lupus erythematosus, erythema multiforme, or epithelial dysplasia [57]. Alternatively, it is possible to culture samples using Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA), from which the Candida species can be identified [45, 47]. This can be useful if infection shows resistance to antifungal agents, as some rarer Candida species (e.g., Candida glabrata) may show enhanced resistance to treatment [47].

In rare cases (0.32% of otherwise healthy individuals in a retrospective single-center study of 88,125 individuals in South Korea) [58], oral Candida infections may extend to the esophagus. Esophageal candidiasis appears endoscopically as thick white plaques on the esophageal mucosa. Symptoms include difficulty or pain upon swallowing or pain behind the sternum [49, 59]. Patients presenting with these symptoms should be referred for esophagoscopy to exclude esophageal candidiasis [49, 60].

If a patient presents with clinical signs of hyperplastic candidiasis, a biopsy should be conducted because of the proposed link between this presentation and malignancy [56].

Treatment of Oral Candidiasis

Patients with psoriasis are encouraged to practice good oral and denture hygiene to prevent the occurrence of oral candidiasis. However, if oral candidiasis occurs, a number of treatments are available, with some applied topically and others administered orally [56]. Generally, as per guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the USA, and the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, initial topical antifungal treatment for 7–14 days is recommended [49, 56, 61, 62]. This can include miconazole oral gel (50 mg mucoadhesive tablet applied daily [USA], or 2.5 mL, four times daily [UK]), clotrimazole troches (10 mg, five times daily [USA]) or “swish and swallow” treatments such as nystatin suspension (100,000 U/mL, 4–6 mL [USA] or 1 mL [UK] four times daily) [61, 62]. If candidiasis does not resolve, oral fluconazole (100–200 mg once daily for 7–14 days [USA], or 50–100 mg once daily for 7 days [UK]) is recommended [49, 61, 62]. Itraconazole (200 mg once daily [USA] or 100–200 mg twice daily [UK]) can be prescribed as an alternative to fluconazole [61, 62]. As the labels of anti-IL-17 medications recommend pausing administration until an infection is resolved, if administration of anti-IL-17 treatment falls on the same day as initiation of antifungal treatment, administration of anti-IL-17 can be postponed for a few days to prioritize resolution of oral candidiasis.

Depending on local guidelines, fluconazole may be prescribed as a first-line treatment for oral candidiasis, as it is highly effective in treating fungal infections and has a simpler dosing schedule compared with topical antifungal treatments [56]. In our experience, shorter durations of fluconazole treatment (e.g., 100–200 mg daily for 3–5 days) can be an effective first-line treatment for oral candidiasis. However, any potential drug–drug interactions should be carefully considered, especially if a patient with psoriasis presents with other comorbidities. If oral candidiasis shows resistance to fluconazole, fungal characterization via SDA culture can be carried out, as previously described [45, 47]. In the case that a fluconazole-resistant Candida species is identified, alternative antifungal treatment should be prescribed.

While the majority of patients respond to these antifungal treatments with quick resolution [56], in certain cases oral candidiasis may be recurrent. If recurrent, measures should be taken to confirm adherence to antifungal treatment and correct any predisposing factors if applicable. This includes education in proper oral and denture hygiene, smoking cessation, rinsing the mouth after use of steroid inhalers, and proper management of diabetes [62]. Poor oral and denture hygiene, in particular, are key risk factors of oral candidiasis and so should be amended in order to prevent reinfection if relevant.

If recurrence continues within a 3-month period following initial treatment, and there is insufficient treatment response with alternative modes of psoriasis treatment, initiation of prophylaxis can be considered. In our clinical experience, this could include administration of any of the aforementioned treatment measures repeated once weekly or monthly for short or longer periods, guided by need and response.

The effectiveness of prophylaxis for the prevention of recurrent oral candidiasis has most frequently been demonstrated in patients with HIV [63]. In these patients, fluconazole prophylaxis has been shown to reduce recurrence as compared with no treatment or placebo [64,65,66,67,68]. However, there is concern that continuous treatment may lead to fluconazole resistance. Indeed, one study found decreased susceptibility of Candida isolates to fluconazole in 56% of patients who received continuous therapy. Nevertheless, the vast majority of patients in this study still showed clearance of oral candidiasis in response to fluconazole [69]. Furthermore, in another study, similar proportions of patients with HIV receiving continuous (4.1%) or episodic (4.3%) fluconazole developed fluconazole-refractory oral candidiasis [70]. For fluconazole-refractory infections, treatment with non-azole antifungals can be considered [61].

Conclusions

Given the increased risk of oral candidiasis in patients with psoriasis receiving anti-IL-17s, dermatologists should be attentive to clinical signs of oral candidiasis and aware of how to manage cases appropriately.

Oral candidiasis in patients with psoriasis is typically mild to moderate in severity. In our clinical experience, cases can be managed with standard antifungal treatment without discontinuing biologic psoriasis therapies. Furthermore, anti-IL-17 treatment is generally not associated with an increased risk of systemic candidiasis or serious infections.

To prevent recurrence of oral candidiasis, patients should be advised to practice good oral hygiene and be provided with information on smoking cessation, if applicable. Prophylaxis with antifungal agents can be considered if there is insufficient treatment response with alternative modes of psoriasis treatment.

References

Polese B, Zhang H, Thurairajah B, King IL. Innate lymphocytes in psoriasis. Front Immunol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00242.

Damiani G, Bragazzi NL, Karimkhani Aksut C, et al. The global, regional, and national burden of psoriasis: results and insights from the global burden of disease 2019 study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.743180.

Blauvelt A, Chiricozzi A. The immunologic role of IL-17 in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis pathogenesis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-018-8702-3.

Prinz I, Sandrock I, Mrowietz U. Interleukin-17 cytokines: effectors and targets in psoriasis—a breakthrough in understanding and treatment. J Exp Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20191397.

Lønnberg AS, Zachariae C, Skov L. Targeting of interleukin-17 in the treatment of psoriasis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014. https://doi.org/10.2147/ccid.S67534.

Blauvelt A, Lebwohl MG, Bissonnette R. IL-23/IL-17A dysfunction phenotypes inform possible clinical effects from anti-IL-17A therapies. J Invest Dermatol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2015.144.

Veldhoen M. Interleukin 17 is a chief orchestrator of immunity. Nat Immunol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3742.

Srenathan U, Steel K, Taams LS. IL-17+ CD8+ T cells: differentiation, phenotype and role in inflammatory disease. Immunol Lett. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imlet.2016.05.001.

Onishi RM, Gaffen SL. Interleukin-17 and its target genes: mechanisms of interleukin-17 function in disease. Immunology. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03240.x.

Matsuzaki G, Umemura M. Interleukin-17 family cytokines in protective immunity against infections: role of hematopoietic cell-derived and non-hematopoietic cell-derived interleukin-17s. Microbiol Immunol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/1348-0421.12560.

Isailovic N, Daigo K, Mantovani A, Selmi C. Interleukin-17 and innate immunity in infections and chronic inflammation. J Autoimmun. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2015.04.006.

Chen K, Kolls JK. Interluekin-17A (IL17A). Gene. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2017.01.016.

Iwakura Y, Ishigame H, Saijo S, Nakae S. Functional specialization of interleukin-17 family members. Immunity. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.012.

Bunte K, Beikler T. Th17 cells and the IL-23/IL-17 axis in the pathogenesis of periodontitis and immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20143394.

Kamiya K, Kishimoto M, Sugai J, Komine M, Ohtsuki M. Risk factors for the development of psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20184347.

Wilson NJ, Boniface K, Chan JR, et al. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni1497.

Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4006.

Curtis MM, Way SS. Interleukin-17 in host defence against bacterial, mycobacterial and fungal pathogens. Immunology. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03017.x.

Netea MG, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW, Kullberg BJ, van de Veerdonk FL. Immune defence against Candida fungal infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3897.

Soltész B, Tóth B, Sarkadi AK, Erdős M, Maródi L. The evolving view of IL-17-mediated immunity in defense against mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans. Int Rev Immunol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.3109/08830185.2015.1049345.

Yano J, Peters BM, Noverr MC, Fidel PL. Novel mechanism behind the immunopathogenesis of vulvovaginal candidiasis: “neutrophil anergy.” Infection Immun. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00684-17.

Jabra-Rizk MA, Kong EF, Tsui C, et al. Candida albicans pathogenesis: fitting within the host-microbe damage response framework. Infect Immun. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.00469-16.

Rosati D, Bruno M, Jaeger M, Ten Oever J, Netea MG. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: an immunological perspective. Microorganisms. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8020144.

Puel A, Cypowyj S, Maródi L, Abel L, Picard C, Casanova JL. Inborn errors of human IL-17 immunity underlie chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACI.0b013e328358cc0b.

Gaffen SL, Moutsopoulos NM. Regulation of host-microbe interactions at oral mucosal barriers by type 17 immunity. Sci Immunol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aau4594.

Verma A, Gaffen SL, Swidergall M. Innate immunity to mucosal Candida infections. J Fungi. 2017. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3040060.

Pietrzak A, Grywalska E, Socha M, et al. Prevalence and possible role of Candida species in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mediators Inflamm. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9602362.

Bedair AA, Darwazeh AM, Al-Aboosi MM. Oral Candida colonization and candidiasis in patients with psoriasis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2012.05.011.

Elsner K, Holstein J, Hilke FJ, et al. Candida colonization in psoriasis. Exp Dermatol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/exd.14263.

Lesan S, Toosi R, Aliakbarzadeh R, et al. Oral Candida colonization and plaque type psoriasis: is there any relationship? J Investig Clin Dent. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/jicd.12335.

Saunte DM, Mrowietz U, Puig L, Zachariae C. Candida infections in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treated with interleukin-17 inhibitors and their practical management. Br J Dermatol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15015.

Lee MP, Wu KK, Lee EB, Wu JJ. Risk for deep fungal infections during IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitor therapy for psoriasis. Cutis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.12788/cutis.0088.

European Medicines Agency. EMEA/H/C/005316—Bimzelx. 2021. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/bimzelx. Accessed Aug, 2021.

Adams R, Maroof A, Baker T, et al. Bimekizumab, a novel humanized IgG1 antibody that neutralizes both IL-17A and IL-17F. Front Immunol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01894.

Reich K, Warren RB, Lebwohl M, et al. Bimekizumab versus secukinumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2102383.

Gordon KB, Foley P, Krueger JG, et al. Bimekizumab efficacy and safety in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BE READY): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised withdrawal phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00126-4.

Ling Y, Puel A. IL-17 and infections. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0001-7310(14)70016-x.

Puel A, Cypowyj S, Bustamante J, et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1200439.

Yang K, Oak ASW, Elewski BE. Use of IL-23 inhibitors for the treatment of plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-020-00578-0.

Baeten D, Adamopoulos IE. IL-23 inhibition in ankylosing spondylitis: where did it go wrong? Front Immunol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.623874.

Song GG, Lee YH. Relative efficacy and safety of secukinumab and guselkumab for the treatment of active psoriatic arthritis: a network meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021. https://doi.org/10.5414/cp203906.

Hellstein JW, Marek CL. Candidiasis: red and white manifestations in the oral cavity. Head Neck Pathol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-019-01004-6.

Vila T, Sultan AS, Montelongo-Jauregui D, Jabra-Rizk MA. Oral candidiasis: a disease of opportunity. J Fungi (Basel). 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof6010015.

Lalla RV, Patton LL, Dongari-Bagtzoglou A. Oral candidiasis: pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment strategies. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2013;41:263–8.

Coronado-Castellote L, Jiménez-Soriano Y. Clinical and microbiological diagnosis of oral candidiasis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2013. https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.51242.

Giannini PJ, Shetty KV. Diagnosis and management of oral candidiasis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2010.09.010.

Lewis MAO, Williams DW. Diagnosis and management of oral candidosis. Br Dent J. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.886.

Barbeau J, Séguin J, Goulet JP, et al. Reassessing the presence of Candida albicans in denture-related stomatitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1067/moe.2003.44.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Candida infections of the mouth, throat, and esophagus. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/thrush/index.html. Accessed Sept, 2021.

Thomas MS, Parolia A, Kundabala M, Vikram M. Asthma and oral health: a review. Aust Dent J. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01226.x.

Kennedy WA, Laurier C, Gautrin D, et al. Occurrence and risk factors of oral candidiasis treated with oral antifungals in seniors using inhaled steroids. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00191-2.

Mun M, Yap T, Alnuaimi AD, Adams GG, McCullough MJ. Oral candidal carriage in asymptomatic patients. Aust Dent J. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj.12335.

Kawashita Y, Funahara M, Yoshimatsu M, et al. A retrospective study of factors associated with the development of oral candidiasis in patients receiving radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: is topical steroid therapy a risk factor for oral candidiasis? Medicine (Baltimore). 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000013073.

Chattopadhyay A, Gray LR, Patton LL, et al. Salivary secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor and oral candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected persons. Infect Immun. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.72.4.1956-1963.2004.

Krishnan P. Fungal infections of the oral mucosa. Indian J Dent Res. 2012. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-9290.107384.

Garcia-Cuesta C, Sarrion-Pérez MG, Bagán JV. Current treatment of oral candidiasis: a literature review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2014. https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.51798.

Farah C, Lynch N, McCullough M. Oral fungal infections: an update for the general practitioner. Aust Dent J. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01198.x.

Choi JH, Lee CG, Lim YJ, Kang HW, Lim CY, Choi JS. Prevalence and risk factors of esophageal candidiasis in healthy individuals: a single center experience in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2013. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2013.54.1.160.

Hoversten P, Kamboj AK, Katzka DA. Infections of the esophagus: an update on risk factors, diagnosis, and management. Dis Esophagus. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/doy094.

Mohamed AA, Lu X-L, Mounmin FA. Diagnosis and treatment of esophageal Candidiasis: current updates. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3585136.

Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ933.

The National Institute for Healthcare Excellence (NICE). How should I manage oral candidiasis in a person aged 16 years or older who is not immunocompromised? In: CKS health topics A to Z. 2021. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/candida-oral/management/adults-young-people-not-immunocompromised/. Accessed Aug, 2021.

Pienaar ED, Young T, Holmes H. Interventions for the prevention and management of oropharyngeal candidiasis associated with HIV infection in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003940.pub3.

Leen CL, Dunbar EM, Ellis ME, Mandal BK. Once-weekly fluconazole to prevent recurrence of oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients with AIDS and AIDS-related complex: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Infect. 1990. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-4453(90)90646-p.

Stevens DA, Greene SI, Lang OS. Thrush can be prevented in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related complex. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 100-mg oral fluconazole daily. Arch Intern Med. 1991. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1991.00400120096018.

Marriott DJ, Jones PD, Hoy JF, Speed BR, Harkness JL. Fluconazole once a week as secondary prophylaxis against oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-infected patients. A double-blind placebo-controlled study. Med J Aust. 1993. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb121784.x.

Pagani JL, Chave JP, Casjka C, Glauser MP, Bille J. Efficacy, tolerability and development of resistance in HIV-positive patients treated with fluconazole for secondary prevention of oropharyngeal candidiasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkf101.

Schuman P, Capps L, Peng G, et al. Weekly fluconazole for the prevention of mucosal candidiasis in women with HIV infection. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. Ann Intern Med. 1997. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-126-9-199705010-00003.

Revankar SG, Kirkpatrick WR, McAtee RK, et al. A randomized trial of continuous or intermittent therapy with fluconazole for oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-infected patients: clinical outcomes and development of fluconazole resistance. Am J Med. 1998. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00137-5.

Goldman M, Cloud GA, Wade KD, et al. A randomized study of the use of fluconazole in continuous versus episodic therapy in patients with advanced HIV infection and a history of oropharyngeal candidiasis: AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 323/Mycoses Study Group Study 40. Clin Infect Dis. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1086/497373.

Acknowledgements

Funding

UCB funded the review and development of the manuscript and reviewed the text to ensure that from the perspective of UCB, the data presented in the publication are scientifically, technically, and medically supportable, that they do not contain any information that has the potential to damage the intellectual property of UCB, and that the publication complies with applicable laws, regulations, guidelines and good industry practice. The authors approved the final version to be published after critically revising the manuscript/publication for important intellectual content. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was also funded by UCB.

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

The authors acknowledge Susanne Wiegratz, MSc, UCB Pharma, Monheim, Germany for publication coordination as well as Kaity McCafferty Layte, BSc, Daniel Smith, BA, and Amelia Frizell-Armitage, PhD, Costello Medical, UK, for writing and editorial assistance funded by UCB Pharma in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines. Richard B. Warren, MD, PhD, is supported by the Manchester NIHR Biomedical Research Centre.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Substantial contributions to the review conception and design: AWA, AB, UM, BS, PG, JFM, RGL, MS, ML, MGN, NNG, RBW; substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of review findings: AWA, AB, UM, BS, PG, JFM, RGL, MS, ML, MGN, NNG, RBW; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: AWA, AB, UM, BS, PG, JFM, RGL, MS, ML, MGN, NNG, RBW; final approval of the version of the article to be published: AWA, AB, UM, BS, PG, JFM, RGL, MS, ML, MGN, NNG, RBW.

Disclosures

April W. Armstrong has served as a data safety monitoring board member for Boehringer Ingelheim/Parexel; received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma; has been a research investigator without compensation for Sanofi Genzyme; has been scientific investigator for AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Modernizing Medicine, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, and Sun Pharma; has served as speaker for AbbVie, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme. Andrew Blauvelt has served as a scientific adviser and/or clinical study investigator for AbbVie, Abcentra, Aligos, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis, Arena, Aslan, Athenex, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Evommune, Forte, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Landos, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Rapt, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Sun Pharma, UCB Pharma, and Vibliome. Ulrich Mrowietz has served as advisor and/or clinical study investigator for, and/or received honoraria and/or grants from AbbVie, Almirall, Aristea, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Eli Lilly, Foamix, Formycon, Forward Pharma, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Medac, Novartis, Phi-Stone, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi Genzyme, and UCB Pharma. Bruce Strober has served as a consultant (honoraria) from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis, Arena, Aristea, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Equillium, GSK, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mindera, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Sun Pharma, and UCB Pharma; has served as speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Ortho Dermatologics; Scientific Director (consulting fee) for CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry; investigator for AbbVie, Cara Therapeutics, CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry, Dermavant, Dermira, and Novartis; Editor-in-Chief (honorarium) for Journal of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. Paolo Gisondi has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Abiogen, Almirall, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi Genzyme, and UCB Pharma. Joseph F. Merola has been a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Bayer, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Regeneron, UCB Pharma; principal investigator for Dermavant, LEO Pharma, and UCB Pharma. Richard G. Langley has been a principal investigator for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB Pharma; served on scientific advisory boards for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma; provided lectures for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer. Mona Ståhle has received honoraria for participating in advisory boards and has given lectures for AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Lipidor, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma. Mark Lebwohl is an employee of Mount Sinai and receives research funds from AbbVie, Amgen, Arcutis, Avotres, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, Ortho Dermatologics, Regeneron, and UCB Pharma and is a consultant for Aditum Bio, Almirall, AltruBio, AnaptysBio, Arcutis, Aristea Therapeutics, Arrive Technologies, Avotres Therapeutics, BiomX, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cara Therapeutics, Castle Biosciences, Corrona, Dermavant Sciences, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Evelo Biosciences, Evommune, Facilitation of International Dermatology Education, Forte Biosciences, Foundation for Research and Education in Dermatology, Helsinn Therapeutics, Hexima, LEO Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mindera, Pfizer, Seanergy, and Verrica. Mihai G. Netea is a scientific founder and shareholder for Trained Therapeutix Discovery and Lemba; has served as a consultant (honoraria) for Inflazome, Roche, and UCB Pharma. Natalie Nunez Gomez is an employee and shareholder of UCB Pharma. Richard B. Warren has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arena, Astellas, Avillion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, GSK, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, UCB Pharma; has received research grants to his institution from AbbVie, Almirall, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, UCB Pharma; honoraria from Astellas, DiCE, GSK, and Union.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Armstrong, A.W., Blauvelt, A., Mrowietz, U. et al. A Practical Guide to the Management of Oral Candidiasis in Patients with Plaque Psoriasis Receiving Treatments That Target Interleukin-17. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 12, 787–800 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00687-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00687-0