Abstract

Introduction

Skin pain (described as discomfort or soreness) is increasingly recognized as a symptom of atopic dermatitis which impacts patient quality of life. This analysis examined the effect of baricitinib on skin pain in atopic dermatitis in three phase 3 studies (BREEZE-AD1, -AD2, and -AD7).

Methods

Patients were randomly assigned 2:1:1:1 to receive once-daily placebo, baricitinib 1 mg, 2 mg, or 4 mg in BREEZE-AD1 (N = 624) and -AD2 (N = 615) and 1:1:1 to receive once-daily placebo, baricitinib 2 mg, or 4 mg, with topical corticosteroids, in BREEZE-AD7 (N = 329) for 16 weeks. Patients recorded their skin pain severity using the Skin Pain Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) via an electronic daily diary. Data were analyzed by study as least squares mean change from baseline in daily scores for the randomly assigned patients using mixed model repeated measures analysis. Analysis of Skin Pain NRS response was done using logistic regression using non-responder imputation.

Results

Baricitinib produced significant percentage change from baseline compared with placebo in patient-reported skin pain severity by day 2 in BREEZE-AD1 (baricitinib 4 mg − 11.9%, p < 0.001; baricitinib 2 mg − 6.4%, p = 0.016; baricitinib 1 mg − 6.2%, p = 0.016), -AD2 (baricitinib 4 mg − 12.6%, p < 0.001; baricitinib 2 mg − 5.6%, p = 0.036; baricitinib 1 mg − 6.9%, p = 0.011), and -AD7 (baricitinib 4 mg − 6.9%, p = 0.04; baricitinib 2 mg − 7.9%, p = 0.018). A greater proportion of patients treated with baricitinib reported at least a 4-point reduction in Skin Pain NRS score at week 16 (Skin Pain NRS responders) in BREEZE-AD1 (baricitinib 4 mg 25.3%, p < 0.001), -AD2 (baricitinib 4 mg 20.0%, p < 0.001; baricitinib 2 mg 19.0%, p < 0.001), and -AD7 (baricitinib 4 mg 48.8%, p < 0.001; baricitinib 2 mg 45.2%, p = 0.004) compared to placebo. A significantly higher proportion of Skin Pain NRS responders also achieved at least a 4-point improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index at week 16 when compared with Skin Pain NRS non-responders in BREEZE-AD1 (89.2%, p < 0.0001), -AD2 (92.5%, p < 0.0001), and -AD7 (88.3%, p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Baricitinib improved patient-reported skin pain severity as early as day 2.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers

BREEZE-AD1, NCT03334396; BREEZE-AD2, NCT03334422; BREEZE-AD7, NCT03733301.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Skin pain (which is described by patients using terms such as discomfort or soreness) is an important symptom in atopic dermatitis (AD) which is not widely recognized by dermatologists or treatment guidelines, despite being one of the most frequently reported symptoms of AD after itch. |

Skin pain can have a substantial impact on patient quality of life but may not be adequately addressed by current treatments. |

This work examined the effect of baricitinib on skin pain severity in AD in three phase 3 studies (BREEZE-AD1, -AD2, and -AD7). |

What was learned from the study? |

Treatment with baricitinib resulted in rapid improvement in patient-reported skin pain severity in AD as early as the first day after first dose administration, i.e., day 2. |

Patients who achieved meaningful improvements in skin pain also demonstrated improvements in Dermatology Life Quality Index, indicating an association between skin pain and quality of life. |

Daily assessment of patient symptoms allows for early detection of treatment effects. |

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic, relapsing, inflammatory skin disease which is characterized by itch (pruritus), erythema, dry and lichenified skin, and papules accompanied by increased risk of cutaneous infection [1,2,3]. A recent study estimated that the prevalence of AD in adults ranges from 2.1% to 4.9% globally [1]; however many people who meet diagnostic criteria for AD may not be formally diagnosed or treated [3]. AD causes a significant burden for patients by impacting mood, sleep, and work productivity, and reducing quality of life, both physical and emotional. Current treatment includes maintenance therapy focusing on the restoration of disrupted barrier function using emollients, the avoidance of triggers, and reactive or proactive use of topical corticosteroids (TCS) and topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) [2, 4]. Moderate-to-severe AD may be treated with immunomodulatory agents such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, or azathioprine. Dupilumab and baricitinib are new treatments that can be used for long-term treatment of moderate-to-severe AD [5, 6].

Skin pain (which is described by patients using terms such as discomfort or soreness) is an important symptom in AD which until recently was not widely recognized by dermatologists or treatment guidelines [7], despite being one of the most frequently reported symptoms of AD after itch [8]. Skin pain can be linked to the severity of AD and itching [9], but it may also be experienced independent of itch and the itch–scratch cycle [10, 11]. There is evidence to suggest that skin pain is a distinct symptom in AD. Patients with AD show exaggerated responses to both itch- and pain-evoking stimuli in lesional and non-lesional skin [12]; the overlap of sensory neurons for itch and pain means that peripheral sensitization associated with itch may also increase sensitivity to pain [7]. The body area affected also influences the level of pain, as higher skin pain scores have been reported in plantar, chest, and palmar areas [13]. Surveys of patients with AD tend to describe their skin pain using neuropathic terms, such as burning, stinging, stabbing, or pinprick-like [7, 9, 14]. Additionally, skin pain, which may not be adequately addressed by current treatments, can have a substantial impact on the quality of life (QoL) of patients [9].

Baricitinib is an oral selective inhibitor of Janus kinase (JAK)1 and JAK2 which is indicated in the European Union and Japan, and being evaluated in the USA and other countries, for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy. The phase 3 randomized, controlled monotherapy studies of baricitinib, BREEZE-AD1 and BREEZE-AD2, and the combination study of baricitinib with TCS, BREEZE-AD7, have shown that baricitinib improved signs and symptoms of AD, and was well tolerated [6, 15].

Baricitinib has been shown to have a rapid effect on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) such as itch and sleep [16]. This analysis shows that a rapid improvement can also be achieved in skin pain and associated QoL measures reported through patient diaries in the studies BREEZE-AD1, BREEZE-AD2, and BREEZE-AD7.

Methods

Study Design

The study designs, patients, assessments, randomization and masking methods, procedures, and outcomes for BREEZE-AD1, BREEZE-AD2, and BREEZE-AD7 have been published previously [6, 15].

Briefly, all three studies included patients with moderate-to-severe AD who had inadequate responses to existing topical therapies. In BREEZE-AD1 (N = 624) and BREEZE-AD2 (N = 615), patients were randomly assigned 2:1:1:1 to placebo, baricitinib 1 mg, 2 mg, or 4 mg once-daily for 16 weeks. In BREEZE-AD7 (N = 329), patients were randomly assigned 1:1:1 to placebo, baricitinib 2 mg, or 4 mg once-daily for 16-weeks and background low-to-moderate potency TCS were allowed for active lesions.

The studies were approved by all institutions involved. Details of the institutions and their ethics committees have been published previously [6, 15]. The studies were performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and its later amendments. All subjects provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

An electronic daily diary was used to record patient symptoms over the previous 24 h. Patients completed the Skin Pain Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), describing their worst skin pain (e.g., discomfort or soreness) in the past 24 h, where 0 = no pain and 10 = worst pain imaginable [14]. QoL was measured using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), a 10-item questionnaire covering six domains with scores ranging from 0 to 30 (higher scores indicating greater impairment of QoL) [17], where patients recorded impact over the previous week.

Statistical Analysis

In this planned exploratory analysis, skin pain data were analyzed by study to compare treatment difference with least squares means (LSM) of change from baseline in Skin Pain NRS scores for weeks 1–16, in which the baseline value was the mean of the seven daily assessments prior to the first dose of study drug. The daily diary Skin Pain NRS scores were used to calculate weekly averages. Mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) analysis was used to analyze change from baseline values. This model used a restricted maximum likelihood estimation, and included treatment, region, baseline disease severity (Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis, vIGA-AD), visit, and treatment-by-visit interaction as fixed categorical effects, and baseline and baseline-by-visit interaction as fixed continuous effects. For daily diary skin pain assessments, the model for analyses up to week 16 included all weekly assessments. Logistic regression was used to analyze the non-responder imputation (NRI) data, with region, baseline disease severity (vIGA-AD), baseline value, and treatment group in the model. Data after any rescue therapy or discontinuation were considered missing from the analysis. Patients who had achieved at least a 4-point improvement in Skin Pain NRS at week 16 were considered to be Skin Pain NRS responders.

The LSM percentage change from baseline in Skin Pain NRS was calculated for daily scores in the first week of treatment (day 1–day 7). The treatment comparisons reported as LSM percentage change from baseline were derived as follows: (LSM change from baseline obtained from the MMRM analysis/overall mean at baseline) × 100. p values for treatment comparisons were not controlled by multiplicity.

All data were analyzed with SAS Version 9.4.

Results

A total of 624, 615, and 329 patients were randomly assigned in BREEZE-AD1, BREEZE-AD2, and BREEZE-AD7, respectively. The baseline demographics and disease characteristics were balanced among treatment groups in all three studies (Table 1).

After 1 week of treatment with baricitinib, all treatment groups in BREEZE-AD1 (baricitinib 1 mg LSM difference − 0.5, p < 0.001; baricitinib 2 mg LSM difference − 0.5, p < 0.001; baricitinib 4 mg LSM difference − 1.0, p < 0.001), BREEZE-AD2 (baricitinib 1 mg LSM difference − 0.5, p < 0.001; baricitinib 2 mg LSM difference − 0.8, p < 0.001; baricitinib 4 mg LSM difference − 1.0, p < 0.001), and BREEZE-AD7 (baricitinib 2 mg LSM difference − 0.6, p = 0.002; baricitinib 4 mg LSM difference − 0.8, p < 0.001) reported significant changes from baseline in Skin Pain NRS when compared with placebo (Fig. 1a, b, c, respectively). This significant improvement in Skin Pain NRS was maintained across the 16-week treatment period for patients who received baricitinib 1 mg and baricitinib 4 mg in BREEZE-AD1, and patients who received baricitinib 2 mg and baricitinib 4 mg in BREEZE-AD2 and BREEZE-AD7. BREEZE-AD7 showed greater changes from baseline for all treatment groups, including placebo, owing to the concomitant use of TCS during the trial.

Least squares mean change from baseline in Skin Pain NRS during 16 weeks of treatment in BREEZE-AD1 (a), BREEZE-AD2 (b), and BREEZE-AD7 (c). *p ≤ 0.05 compared with placebo; **p ≤ 0.01 compared with placebo; ***p < 0.001 compared with placebo. Bari baricitinib, LSM least squares mean, NRS numerical rating scale, PBO placebo, SE standard error, TCS topical corticosteroids

When assessing the percentage change from baseline in daily Skin Pain NRS scores during the first week of treatment, a significant change was seen as early as the first day after first dose administration (day 2) for some treatment groups versus placebo in BREEZE-AD1 (baricitinib 4 mg LSM percentage change difference − 11.9%, p < 0.001; baricitinib 2 mg − 6.4%, p = 0.016; baricitinib 1 mg − 6.2%, p = 0.016), BREEZE-AD2 (baricitinib 4 mg LSM percentage change difference − 12.6%, p < 0.001; baricitinib 2 mg − 5.6%, p = 0.036; baricitinib 1 mg − 6.9%, p = 0.011), and BREEZE-AD7 (baricitinib 4 mg LSM percentage change difference − 6.9, p = 0.04; baricitinib 2 mg LSM percentage change difference − 7.9, p = 0.018) (Fig. 2a, b, c, respectively).

Least squares mean percentage change from baseline in Skin Pain NRS during the first week of treatment in BREEZE-AD1 (a), BREEZE-AD2 (b), and BREEZE-AD7 (c). *p ≤ 0.05 compared with placebo; **p ≤ 0.01 compared with placebo; ***p < 0.001 compared with placebo; arrows indicate the first day of treatment administration. Bari baricitinib, LSM least squares mean, NRS numerical rating scale, PBO placebo, TCS topical corticosteroids

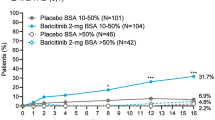

A significantly greater proportion of patients treated with baricitinib achieved a clinically meaningful response of at least a 4-point improvement in Skin Pain NRS compared to those in the placebo groups in BREEZE-AD1, BREEZE-AD2, and BREEZE-AD7. After 1 week of treatment, the baricitinib 4 mg group in BREEZE-AD1 (3.3%, p = 0.043), BREEZE-AD2 (5.3%, p = 0.028), and BREEZE-AD7 (11.6%, p = 0.027) showed significantly higher proportion of patients achieving at least a 4-point improvement in Skin Pain NRS versus placebo (Fig. 3a, b, c, respectively). This improvement in skin pain severity increases with longer treatment duration, reaching a plateau at approximately week 5 in BREEZE-AD1, week 4 in BREEZE-AD2, and week 3 in BREEZE-AD7 for the baricitinib 4 mg groups. A statistically significant proportion of patients achieving response was observed throughout the majority of the treatment duration by patients receiving baricitinib 4 mg in BREEZE-AD1, baricitinib 2 mg and 4 mg in BREEZE-AD2, and baricitinib 2 mg and 4 mg in BREEZE-AD7 when compared with placebo. At week 16, 25.3% of patients (baricitinib 4 mg; p < 0.001) in BREEZE-AD1, 20.0% (baricitinib 4 mg; p < 0.001) and 19.0% (baricitinib 2 mg; p < 0.001) of patients in BREEZE-AD2, and 48.8% (baricitinib 4 mg; p < 0.001) and 45.2% (baricitinib 2 mg; p = 0.004) of patients in BREEZE-AD7 had achieved at least a 4-point improvement in Skin Pain NRS and were considered to be Skin Pain NRS responders.

Percent response of patients achieving at least a 4-point improvement from baseline in Skin Pain NRS during 16 weeks of treatment in BREEZE-AD1 (a), BREEZE-AD2 (b), and BREEZE-AD7 (c). *p ≤ 0.05 compared with placebo; **p ≤ 0.01 compared with placebo; ***p < 0.001 compared with placebo. Bari baricitinib, CI confidence interval, NRS numerical rating scale, PBO placebo, TCS topical corticosteroids

For Skin Pain NRS responders, a significantly larger proportion of patients also achieved at least a 4-point improvement in DLQI score at week 16, when compared to the proportion of Skin Pain NRS non-responders (patients who achieved less than a 4-point improvement in Skin Pain NRS at week 16) who achieved at least a 4-point improvement in DLQI in BREEZE-AD1 (89.2% vs 17.4%, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4a), BREEZE-AD2 (92.5% vs 11.8%, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4b), and BREEZE-AD7 (88.3% vs 46.8%, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4c). This indicates that improvement in skin pain was associated with a positive impact on patient QoL.

Patients achieving at least a 4-point improvement in DLQI among Skin Pain NRS responders (at least a 4-point improvement in Skin Pain NRS) vs non-responders (less than a 4-point improvement in Skin Pain NRS) at week 16 in BREEZE-AD1 (a), BREEZE-AD2 (b), and BREEZE-AD7 (c). ***p < 0.0001. CI confidence interval, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, NRS numerical rating scale

Discussion

This analysis of patient-reported data in BREEZE-AD1, BREEZE-AD2, and BREEZE-AD7 showed that treatment with baricitinib resulted in rapid improvement in skin pain, with results seen as early as the first day after first dose administration (day 2). The effect of baricitinib on skin pain was observed throughout the 16-week treatment period in these trials, and a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with baricitinib achieved clinically meaningful improvements in Skin Pain NRS when compared to the placebo groups.

Patients who achieved meaningful improvements in skin pain also demonstrated improvements in DLQI score, indicating an association between skin pain and QoL in this analysis alongside other factors such as itch and sleep. However, the numbers of patients achieving the status of Skin Pain NRS responder in BREEZE-AD1 and BREEZE-AD2 were quite small, at N = 65 and N = 53, respectively. This may have an impact on the analysis. Owing to the concomitant use of TCS in BREEZE-AD7, a larger proportion of patients achieved the Skin Pain NRS response end point compared with the BREEZE-AD1 and BREEZE-AD2 trials (N = 103), and a larger proportion of Skin Pain NRS non-responders achieved at least a 4-point improvement in DLQI score. Despite differences in absolute Skin Pain NRS response rates, drug–placebo differences were similar across studies.

These data further support previous findings that baricitinib provides rapid and durable relief for patients with AD [6, 15]. A recent report has also shown rapid improvements in itch severity and sleep disturbance after treatment with baricitinib [16]. Similar to the improvements in skin pain, a significant reduction in itch severity is observed on the first day after first dose administration (day 2), as well as improvements seen in patients’ ability to fall asleep, waking due to itch, and ability to return to sleep after being woken by itch. This analysis, along with previously published work [18], also shows that daily assessment of patient symptoms allows for early detection of treatment effects.

The implications of this work are important for patients because of the impact that the symptom of skin pain in AD has on QoL, interfering with mental health, sleep, socializing and leisure activities, and daily living [9, 19]. Skin pain is common in AD, with up to 61% of patients reporting that they experience this symptom and 14% describing the pain as severe or very severe [9, 10]. The mean Skin Pain NRS score in BREEZE-AD1, BREEZE-AD2, and BREEZE-AD7 ranged from 5.5 to 6.8 among the different treatment groups [6, 15]. Although patients with moderate and severe AD report higher levels of skin pain than the general population irrespective of disease control, these patients do not appear to use analgesic medication to relieve this pain [13, 20]. Therefore, systemic medications for the treatment of AD such as baricitinib may fulfill an unmet need of these patients suffering from skin pain.

Currently, there is no formal guidance on the treatment of skin pain in patients with AD as this symptom is often insufficiently acknowledged by treating physicians because of its perceived association with itch [9]. Emollients have not been shown to have any direct action on skin pain but may have a protective effect against the formation of painful lesions by reducing the number of flares [21], whereas TCI may induce pain hypersensitivity resulting in a burning sensation on application [22]. However, many of the treatments for AD which have been shown to have efficacy against itch have been poorly studied for their effect on skin pain [23], and some patients still experience skin pain despite otherwise controlled disease [20]. A recent position paper has proposed a new treatment algorithm for the management of both itch and skin pain in patients with AD, where common analgesics, gabapentinoids, antidepressants, JAK inhibitors, topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, and µ-opioids could be considered to treat skin pain which persists following initial AD treatments [23].

Cytokines such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), interleukin (IL)-4, IL-31, and IL-13 have been implicated in itch in AD via the histamine-independent pathway. These cytokines can stimulate the transmission of pruritic signals along C-fibers by binding to the appropriate receptor on peripheral nerve endings, causing electrical signaling, Ca2+ influx, and activation of JAK-signal transducer and activation of transcription (STAT) signaling pathways [24, 25]. JAK-STAT signaling results in the promotion of gene expression associated with impaired keratinocyte differentiation and pruritus, and chronic pruritus causes activation of STAT3 in astrocytes of the spinal dorsal horn [24, 25]. Baricitinib, by blocking the activity of JAK1 and JAK2, can prevent the pruritogenic signals of the IL-31 pathway by preventing the phosphorylation of STAT proteins and their downstream effects [25]. As the sensory neurons for itch overlap with those of pain [7], the mechanism by which baricitinib controls itch in AD may also explain the effect on skin pain in these patients.

Limitations of this work are that it was an exploratory analysis, the specific anatomical locations where the skin pain originated were not identified, and that symptoms reported by study participants may not have been reported consistently. Therefore, the data should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

Baricitinib monotherapy showed a rapid onset of action, within days of the first dose, for the clinically burdensome symptom of skin pain in patients with moderate-to-severe AD. This effect on skin pain may also influence patient QoL, as demonstrated by improvements in DLQI in the skin pain responder group. This analysis further supports the use of baricitinib in the treatment of AD.

References

Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: results from an international survey. Allergy. 2018;73:1284–93.

Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Guttman-Yassky E, Ong PY, Silverberg J, Farrar JR. Atopic dermatitis yardstick: practical recommendations for an evolving therapeutic landscape. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120:10-22e2.

Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Atopic dermatitis in US adults: from population to health care utilization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:1524–32.

Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:657–82.

Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:850–78.

Reich K, Kabashima K, Peris K, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib combined with topical corticosteroids for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1333–43.

Stander S, Simpson EL, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Clinical relevance of skin pain in atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:921–6.

Grant L, Seiding Larsen L, Trennery C, et al. Conceptual model to illustrate the symptom experience and humanistic burden associated with atopic dermatitis in adults and adolescents. Dermatitis. 2019;30:247–54.

Vakharia PP, Chopra R, Sacotte R, et al. Burden of skin pain in atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119:548-52.e3.

Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Pain is a common and burdensome symptom of atopic dermatitis in United States adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2699-706.e7.

Hong MR, Lei D, Yousaf M, Chavda R, Gabriel S, Silverberg JI. A real-world study of the longitudinal course of skin pain in adult atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.021.

Andersen HH, Elberling J, Solvsten H, Yosipovitch G, Arendt-Nielsen L. Nonhistaminergic and mechanical itch sensitization in atopic dermatitis. Pain. 2017;158:1780–91.

Thyssen JP, Halling-Sonderby AS, Wu JJ, Egeberg A. Pain severity and use of analgesic medication in adults with atopic dermatitis: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1430–6.

Newton L, DeLozier AM, Griffiths PC, et al. Exploring content and psychometric validity of newly developed assessment tools for itch and skin pain in atopic dermatitis. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2019;3:42.

Simpson EL, Lacour JP, Spelman L, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to topical corticosteroids: results from two randomized monotherapy phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:242–55.

Buhl T, Rosmarin D, Serra-Baldrich E, et al. Itch and sleep improvements with baricitinib in patients with atopic dermatitis: a post hoc analysis of 3 phase 3 studies. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-021-00534-8.

Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–6.

Silverberg JI, Paul C, Wollenberg A, et al. Onset of effect on symptoms reported in daily diaries in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with baricitinib: results from two phase 3 trials. J Cutan Med Surg. 2020;24:72S.

Maarouf M, Kromenacker B, Capozza KL, et al. Pain and itch are dual burdens in atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2018;29:278–81.

Simpson EL, Guttman-Yassky E, Margolis DJ, et al. Association of inadequately controlled disease and disease severity with patient-reported disease burden in adults with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:903–12.

Hebert AA, Rippke F, Weber TM, Nicol NH. Efficacy of nonprescription moisturizers for atopic dermatitis: an updated review of clinical evidence. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:641–55.

Pereira U, Boulais N, Lebonvallet N, Pennec JP, Dorange G, Misery L. Mechanisms of the sensory effects of tacrolimus on the skin. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:70–7.

Misery L, Belloni Fortina A, El Hachem M, et al. A position paper on the management of itch and pain in atopic dermatitis from the International Society of Atopic Dermatitis (ISAD)/Oriented Patient-Education Network in Dermatology (OPENED) task force. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:787–96.

Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1.

Paller AS, Kabashima K, Bieber T. Therapeutic pipeline for atopic dermatitis: end of the drought? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:633–43.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients, their families, the study sites, and the study personnel who participated in the BREEZE-AD1, BREEZE-AD2, and BREEZE-AD7 studies.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company, under license from Incyte Corporation. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author’s Contributions

Amy DeLozier and Marta Casillas conceived and designed the study and analysis. Timo Buhl and Pablo Fernandez-Peñas were investigators and collected the data. Sherry Chen and Na Lu conducted the statistical analyses. Jacob P. Thyssen, Kenji Kabashima, and Sonja Ständer interpreted the data. All the authors had full access to all the data reported in the study and were involved in critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Catherine Lynch, a full-time employee of Eli Lilly and Company, assisted with manuscript preparation and process support.

Disclosures

Jacob P. Thyssen has served on advisory boards, acted as a speaker, or acted as an investigator for AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi-Genzyme; and has received grants/research support from Regeneron and Sanofi-Genzyme. Timo Buhl has received honoraria for lectures and advisory boards from ALK Abello, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, MEDA, Novartis, and Sanofi; and has received research grants from Eli Lilly and Company, Kiniksa, Philips, and Thermo Fisher. Pablo Fernández-Peñas has received grants/clinical trial contracts from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BMS, CSL, Eli Lilly and Company, Eisai, Galderma, Janssen, Jiansu Hengrui, miRagen, Novartis, Oncosec, Pfizer, Sun Pharma, and UCB; received honoraria or consultation fees from AbbVie, Amgen, BI, BMS, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Leo, Merck-Serono, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, and UCB; and received compassionate supply of medication from AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, and Novartis. Kenji Kabashima has received consulting fees, honoraria, grant support, and lecturing fees from Japan Tobacco, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Ono Pharmaceutical, Procter & Gamble, Sanofi, Taiho, and Torii Pharmaceutical. Sherry Chen is a full-time employee of Tigermed. Na Lu is a consultant of IQVIA. Amy DeLozier and Marta Casillas are full-time employees, and own stock in, Eli Lilly and Company. Sonja Ständer has acted as an investigator for Dermasence, Galderma, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals, Menlo Therapeutics, Trevi Therapeutics, Novartis, Sanofi, and Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc.; and has acted as a consultant, speaker, and/or served on advisory boards for Almirall, Bayer, Beiersdorf, Bellus Health, Bionorica, Cara Therapeutics, Celgene, Clexio Biosciences, DS Biopharma, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Perrigo, and Trevi Therapeutics.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The studies were approved by all institutions. Details of the institutions and their ethics committees have been previously published [6, 15]. The studies were performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and its later amendments. All subjects provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Data Availability

Eli Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the USA and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

Prior Presentation

These data were previously presented in part at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Congress; Madrid, Spain; 9–13 October 2019 (Silverberg J, et al. EADV 2019. FC07.03) and EADV Congress, Vienna, Austria (virtual event), 28 October–1 November 2020 (Buhl T, et al. EADV 2020. Virtual Meeting. P0231).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thyssen, J.P., Buhl, T., Fernández-Peñas, P. et al. Baricitinib Rapidly Improves Skin Pain Resulting in Improved Quality of Life for Patients with Atopic Dermatitis: Analyses from BREEZE-AD1, 2, and 7. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 11, 1599–1611 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-021-00577-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-021-00577-x