Abstract

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (FMF) is a particular subtype of mycosis fungoides (MF), characterized by an infiltration of neoplastic CD4+ T cells in the epidermis which can spread to all follicular structures, sebaceous glands, sweat glands and hair follicles. Clinically, FMF can exhibit various cutaneous symptoms. However, these symptoms often occur on the scalp, face and neck, which are rarely affected by conventional MF. We report cicatricial alopecia in a patient with FMF as alopecia lymphomatica. This peculiar symptom should be kept in mind as a critical differential diagnosis of scarring alopecia, leading to further investigation. Thus, an early diagnosis of FMF may be obtained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (FMF) is a rare, but potentially aggressive subtype of a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). It occurs particularly in men, and can frequently involve the scalp, face, and neck. One eye-catching manifestation of FMF is scarring alopecia. |

It is generally assumed that the prognosis of FMF is worse than that of classical MF. An early detection of FMF is hence generally to be pursued, since it concerns CTCL with possible serious consequences. |

In any case of alopecia, a dermoscopic examination should first be made, and if the source of scarring alopecia is still unclear, a skin biopsy is needed to clarify the cause of hair root destruction, because FMF may be hidden behind a scarring alopecia. |

The prognosis of FMF ranges from indolent localized cutaneous T-cell lymphoma to aggressive generalized tumor growth. Lifelong clinical controls are recommended. |

Introduction

Mycosis fungoides (MF), the most common cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), typically presents in its early stage as inflammatory erythematous patches or plaques. Epidermotropism is the histopathologic hallmark of the disease. The rather harmless early stage can persist for a long time before it relatively rarely turns into a tumor stage. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (FMF) is a quite rare, but aggressive subtype of MF [1, 2]. It is found more often in men, and frequently involves the scalp, face, and neck, which are usually spared in conventional MF. FMF typically comes with a wide spectrum of symptoms [3], which makes diagnosis sometimes difficult. One eye-catching manifestation is scarring alopecia, which is often accompanied by loss of eyebrow hair [4]. Keeping that in mind, in all cases of patchy hair loss, first of all differentiation of non-scarring from scarring alopecia is important, especially when symptoms other than on the scalp are discrete or non-existent. FMF has a worse prognosis than conventional MF and an unfavorable 5-year overall survival rate [5]. It remains unclear when and which MF patients will enter the aggressive tumor stage; however, at all events it is critical to diagnose FMF as early as possible.

After having obtained the patient´s permission for publication, we present the case of a male patient with scarring alopecia, a relevant clinical finding of FMF.

Case

A 59-year-old male patient with extensive hair loss on the right side of the scalp presented to our clinic for further therapy under the suspected diagnosis of alopecia areata. The hair loss had already existed for several years and was slowly worsening. The patient also reported the occasional appearance of firmly adhering scales in this area. No complaints of itching, burning or pain were made. There was also a recent history of arterial hypertension, which had been treated by oral medication.

On physical examination, we found a hairless area which involved half of the occipital and nuchal capillitium (Fig. 1). On dermoscopy a scarring alopecia with loss of the adnexal structures was visible (Fig. 2). Full body examination revealed follicular hyperkeratotic papules on both lower legs, with comedones and cysts on the abdomen (Fig. 3). Regional lymph nodes were not palpable. A full blood count, liver, kidney, and thyroid function parameters, including C-reactive protein (CRP) were all found to be in the normal range; also, an antinuclear antibody screen (ANA titer) was unremarkable.

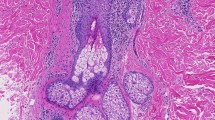

Biopsies of the capillitium, lower leg, and abdomen showed epidermotropism and folliculotropism of lymphocytes with destruction of hair follicles consistent with MF (Fig. 4). Mucin deposits were not present. Molecular histoanalysis (C. Röcken, W. Klapper, I. Oschlies, Institute of Pathology, Kiel, Germany) revealed a T-cell receptor clone with the same rearrangement pattern at all three locations of biopsies. Based on clinical findings and histopathology review, we diagnosed FMF, its leading clinical symptom being scarring alopecia. We did a chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasound, blood smear for Sézary cells, and CD4/CD8 ratio: results were normal. Ultrasound of all lymph node stations revealed enlarged inguinal and axillary lymph nodes on both sides. Referring to the WHO/EORTC [6] classification for cutaneous T cell lymphomas, at present the patient´s disease is a stage IB (T2 NX M0 B0 M0).

We initiated a combination therapy of topical class III steroids and PUVA. After 3 months of treatment, progression had stopped and some improvement of symptoms on trunk and limbs could be observed.

Discussion

It is generally assumed that the prognosis of FMF is worse than that of classical MF [5]. The infiltration of deeper structures, a poor response to topical therapy and a delayed diagnosis are reasons for that. FMF is clinically characterized by patches, perifollicular papules and discrete plaques; and histologically by a low infiltration of a few small neoplastic lymphocytes. It frequently involves the scalp, face, and neck. With MF, most patients remain in the early patch and plaque stage for life. It still remains unclear when and which patients will enter into the aggressive tumor stage.

Histopathologically, FMF shows an infiltration of neoplastic CD4+ T cells in the epidermis and its adnexa. Keratinocytes loosened up by mucin deposition is typical and characteristic of discrete clinical plaques, but in the early stages this may be absent. The own entity of an alopecia mucinosa, follicular papules and plaques with hair loss and histological evidence of epithelial mucin, is subject of scientific discussion. Böer et al. [7] distinguish an epithelial mucinosis and FMF with mucin deposition. In the latter, mucin deposition results from the infiltration of neoplastic cells which, in early stages, may be absent. Its prognosis is similar to that of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Our patient presented with the conspicuous symptom of a circumscribed alopecia. More often than MF the subtype FMF involves the scalp, face, and neck. Although a case of alopecia universalis has been described associated with cutaneous T cell lymphoma [8]. The patchy hair loss of our patient at first glance had been diagnosed as alopecia areata.

A valuable means of differentiating alopecia areata from scarring alopecia is dermoscopy [9]. The outstanding dermoscopic feature of alopecia areata—a non-scarring alopecia—is yellow dots, which means visible follicular openings with hyperkeratotic plugs [10]. In our patient, however, dermoscopic examination did not reveal any follicular openings in the hairless areas confirming a scarring alopecia. Although the literature is sparse, numerous dermoscopic features have been described in patients with FMF: a white halo around the follicle, comedo-like openings, white structureless areas, dotted/fine linear vessels, and dilatation of follicular openings [11,12,13,14,15]. However, dermoscopic presentations in FMF are heterogeneous, which goes together with the broad clinical spectrum of the disease [16]. Therefore, the role of dermoscopy in identification of scarring alopecia, unlike alopecia areata is, for the time being, rather limited [17]. Additional studies are hence needed to further evaluate the prognostic values of dermoscopy in FMF [16, 17]. If the source of scarring alopecia remains unclear, it is most important to clarify the cause of hair root destruction by means of a biopsy [17].

Additional findings of disseminated follicular papules, comedones, and cysts were made on the abdomen and on both lower legs. However, diminished eyebrows and pruritus, typical features of FMF, were not present. Early stage FMF was finally diagnosed by histopathological investigation and subsequent molecular analysis.

According to the German S2k guideline for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [18], a combination therapy of topical class III steroids and PUVA is first-line option for FMF in the early stage. Currently, topical treatment with imiquimod 5% cream may also be helpful [19]. However, symptomatic topical treatments need, in general, to be carried out over a long period of time. If the response is inadequate and the tumor stage is advanced, systemic therapy with retinoids (e.g., bexarotene), methotrexate, or doxorubicin and, if necessary, extracorporeal photopheresis; moreover localized and whole-body radiotherapy resp. can be used. Currently, only allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can cure MF, respectively FMF, which is considered for patients with advanced stages.

Conclusions

In every case of alopecia, a dermoscopic examination should be performed. It is easily done and a valuable means of differentiating alopecia areata from scarring alopecia. In case of doubt, a skin biopsy for histopathological investigation should be done in order to further evaluate the nature of the hair loss. The observed alopecia may prove to be a scarring alopecia as a symptom of folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (FMF), a rare, difficult to diagnose [20, 21], and potentially aggressive subtype of a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). For this unique clinical finding we propose the term alopecia lymphomatica to recognize this rare but potentially dangerous form of scarring alopecia which should be clearly distinguished from other types of scarring hair loss [22].

The prognosis of FMF ranges from indolent localized CTCL to aggressive generalized tumor growth. Allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, considered for patients with advanced stages, is currently the only therapy with curative intent [23]. At present general treatment approaches remain palliative and focus on the patient’s health-related quality of life. Hence, lifelong clinical follow-ups should be recommended.

References

Gerami P, Rosen S, Kuzel T, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides: an aggressive variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(6):738–46.

Feng H, Beasley J, Meeehan S, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030.

Baykal C, Atci T, Sari SO, et al. Neglected clinical features of folliculotropic mycosis fungoides: a large clinical case series. JDDG. 2017;15:289–301.

Bi MY, Curry JL, Christiano AM, et al. The spectrum of hair loss in patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:53–63.

van Santen S, Roach RE, van Doorn R, et al. Clinical staging and prognostic factors in folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(9):992–1000.

Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105(10):3768–85.

Böer A, Guo Y, Ackerman AB. Alopecia mucinosa is mycosis fungoides. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:33–52.

Miteva M, Shabrawi-Caelen L, Fink-Puches R, et al. Alopecia universalis associated with cutaneous T Cell lymphoma. Dermatology. 2014;229:65–9.

Miteva M, Tosti A. Hair and scalp dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1040–8.

Rudnicka l, Olszewska M, Rakowska A (eds). Atlas of Trichoscopy. London: Springer; 2012.

Ghahramani GK, Goetz KE, Liu V. Dermoscopic characterization of cutaneous lymphomas: a pilot survey. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:339–43.

Toncic RJ, Drvar DL, Bradamante M, et al. Early dermoscopic sign of folliculotropism in patients with mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:328–9.

Slawinska M, Sobjanek M, Olszewska B, et al. Trichoscopic spectrum of folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:e107–e108108.

Souissi A, Bellagha I, Jendoubi F, et al. Spiky follicular mycosis fungoides: a trichoscopic feature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:e252–e253253.

Errichetti E, Piccirillo A, Chiacchio R. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides presenting as non-inflammatory scarring scalp alopecia associated with comedo-like lesions. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e37–e55.

Geller S, Rishpon A, Myskowski P. Dermoscopy in folliculotropic mycosis fungoides—a possible mimicker of follicle-based inflammatory and infectious disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:e75–e7676.

Errichetti E, Durdu M. Reply: application of dermoscopy in folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:e77–e78.

Kutane Lymphome, Reg.nummer 032–027, Klassifikation S2k. The Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e.V., AWMF). www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/032-027.html.

Shalabi D, Vadalia N, Nikbakht N. Revisiting imiquimod for treatment of folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. A case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2019;9:807–14.

Iorizzo M, Shabrawi-Caelen L, Vincenzi C, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides masquerading as alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e50–e5252.

Bidier M, Pushkarevskaya A, Enk A, et al. Mycosis fungoides with CD30-positive large-cell transformation clinically mimicking scarring alopecia. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;10:1021–3.

Pileri A, Agostinelli C, Bruni F, et al. Alopecia areata-like mycosis fungoides: lions for lambs. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:293–5.

Johnson WT, Mukherji R, Kartan S, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in advanced stage mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a concise review. Chin Clin Oncol. 2019;1:12–25.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patient for participation.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study and no Rapid Service Fee was received by the journal for the publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Katharina Kreutzer and Isaak Effendy have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the article.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12674471.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kreutzer, K.M., Effendy, I. Cicatricial Alopecia Related to Folliculotropic Mycosis Fungoides. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 10, 1175–1180 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-020-00429-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-020-00429-0