Abstract

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides (FMF) is an aggressive variant of mycosis fungoides (MF) characterized by infiltration of the hair follicle epithelium by neoplastic T cells. FMF demonstrates poor response rates to standard skin-directed therapies such as phototherapy and topical corticosteroids. Imiquimod, an immunomodulatory agent that stimulates the antitumor immune response, has been used successfully in treatment of early-stage MF. We report a 21-year-old patient with unilesional FMF who achieved clinical remission with imiquimod application. This case highlights a potential for use of imiquimod as a treatment option for patients with FMF and limited skin involvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common variant of cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) and is primarily characterized by the proliferation of neoplastic CD4+ T cells in the skin [1]. Early-stage MF presents as patches and plaques that may progress to a more advanced stage with tumors, blood, lymph node or visceral involvement [2]. Several skin-directed therapies (SDTs), including topical corticosteroids, phototherapy, mechlorethamine gel, and topical retinoids, are commonly used in the treatment of early-stage MF [3,4,5].

Folliculotropic MF (FMF) is an aggressive subtype of MF with distinct histopathological features demonstrating the infiltration of the pilosebaceous unit with atypical CD4+ T cells. Clinically, it has variable presentations and can frequently involve the scalp and face, areas spared in classic MF [6, 7]. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides is associated with worse prognosis than conventional MF and has a poor 5-year overall survival rate [6, 8, 9]. More importantly, it has often been difficult to treat FMF patients with the standard SDTs used in classic MF, with many patients being refractory to initial treatments and requiring systemic medications earlier [6, 8]. It is proposed that the deep extension of lymphocytes into the follicular units may limit the response to superficial therapies such as phototherapy and topical corticosteroids [8, 10].

Imiquimod, a topical immune modulator that activates toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7), has demonstrated therapeutic benefit in small case series of MF patients [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. When applied on MF lesional skin, it often creates erosions or ulcerations, presumably by triggering an exuberant immune response with significant depth [12, 14, 17]. Thus, the inflammatory response triggered by imiquimod may be of sufficient depth to target the deeper folliculotropic lymphocytes in FMF. Herein, we present the case of a young female with a single FMF lesion whom we successfully treated with topical imiquimod application. Informed consent for publication was obtained from all patients for whom identifying information is included in this article.

Case

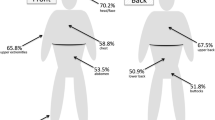

A 21-year-old female patient initially presented to our cutaneous lymphoma clinic after histopathology findings of a single persistent lesion on the breast were concerning for MF. The lesion had been present for approximately one year despite three months of treatment with topical corticosteroids; it was pruritic but not painful. Physical examination revealed a pink 1.5-cm indurated plaque with mild surrounding erythema on the left anteromedial breast. The patient had no other lesions and no lymphadenopathy. Histopathology review revealed atypical CD4+ lymphocytes infiltrating the follicular epithelium, consistent with FMF (Fig. 1a, b). Immunohistochemistry analysis showed predominantly CD3+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1c) with an increase in CD4/CD8 ratio. Peripheral blood flow cytometric analysis revealed no abnormal cell populations.

Topical steroid was discontinued, and treatment with daily topical 5% imiquimod was started. One month after therapy, the patient presented with an indurated plaque with shallow erosions and reported some application-site irritation and pruritus. After another month of treatment, shallow ulcerations developed at the site (Fig. 2a). At this visit, imiquimod therapy was discontinued. One month after imiquimod discontinuation, the plaque had completely resolved, leaving an atrophic pink patch without scale (Fig. 2b). There was no reappearance of the lesion on follow-up five months after imiquimod discontinuation.

Discussion

Unlike conventional MF, patients with FMF demonstrate poor response rates to SDTs. In Gerami et al.’s study, 13 of 43 patients with FMF received SDTs as initial therapy, including topical corticosteroids, psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA), narrow-band ultraviolet B, localized irradiation, nitrogen mustard, and topical bexarotene [6]. Only three patients demonstrated a partial response (PR) or complete response (CR), with two of these patients requiring localized irradiation to achieve this effect. More importantly, patients who showed PR or CR had limited disease with less than 3% body surface area involvement. Therefore, in cases of FMF with limited skin involvement, potent SDTs may be effective. Similarly, imiquimod therapy in our patient with limited skin involvement led to an exuberant reaction and demonstrated efficacy in FMF.

Several studies indicate that the innate and cytotoxic antitumor responses in MF are dysfunctional. This is supported by reduced T-helper type 1(Th1) activity levels and proinflammatory cytokines including interferon (IFN)-α, IFN-γ, and interleukin (IL)-12 [20, 21] and a dominant T-helper type 2 (Th2) phenotype [22, 23]. FMF is a distinct entity with a similar pathogenesis, consisting of a CD4+ lymphocytic infiltrate with a shift towards a Th2 environment [6]. Therefore, therapies that can promote immune activation and enhance the Th1 response can be beneficial in both MF and FMF. One example of such therapies that can be used topically is imiquimod.

Imiquimod is an immunomodulatory agent that induces TLR7 activity on plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Once activated, TLR7 signaling leads to release of proinflammatory cytokines including IFN-α, IFN-γ, and IL-12 that promote the innate immune response and shift the microenvironment to a Th1-dominant milieu [24, 25]. Subsequently, imiquimod enhances antigen presentation and cellular cytotoxicity, inducing an effective antitumor response [26]. It is likely that the exuberant skin reaction that occurred in our patient resulted from the release of imiquimod-induced proinflammatory cytokines. A subsequent increase in the antitumor immune response might have led to the resolution of her lymphoma lesion.

Several small-scale studies describe imiquimod’s efficacy in early-stage MF (Table 1) [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19, 27]. In our review of these studies, we found a total of 24 MF patients, stage IA–IIB, treated with topical imiquimod therapy. Only one patient was identified with FMF [18]. In patients who had documented clearance of treated lesions (N = 13, 54%), CR was achieved after an average of 4.3 months of imiquimod treatment. Patients who developed more severe inflammatory skin reactions were more likely to achieve clearance of their lymphoma lesions. We did not notice an association between time to CR with imiquimod and number of prior treatments or presence of simultaneous treatments. Interestingly, in one case, imiquimod treatment potentiated the patient’s response to PUVA [12]. As expected, the most commonly reported adverse events were skin reactions including erythema, erosions, and ulcerations at the site of application.

Conclusions

Our patient with FMF who failed to respond to topical steroid treatment achieved CR after 2 months of imiquimod therapy. Given the tendency of FMF to resist SDTs, the rapid response to imiquimod observed in this case supports the unique role of topical imiquimod as an early treatment agent for FMF subtype with limited skin involvement. Overall, these findings highlight the need for large-scale studies to evaluate efficacy of imiquimod in treatment of MF and FMF.

References

Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105(10):3768–85.

Scarisbrick JJ. Staging and management of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31(2):181–6.

Lindahl LM, Fenger-Gron M, Iversen L. Topical nitrogen mustard therapy in patients with mycosis fungoides or parapsoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(2):163–8.

Hoppe RT, Abel EA, Deneau DG, et al. Mycosis fungoides: management with topical nitrogen mustard. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5(11):1796–803.

Breneman D, Duvic M, Kuzel T, et al. Phase 1 and 2 trial of bexarotene gel for skin-directed treatment of patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(3):325–32.

Gerami P, Rosen S, Kuzel T, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides: an aggressive variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(6):738–46.

Lehman JS, Cook-Norris RH, Weed BR, et al. Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides: single-center study and systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(6):607–13.

van Doorn R, Scheffer E, Willemze R. Follicular mycosis fungoides, a distinct disease entity with or without associated follicular mucinosis: a clinicopathologic and follow-up study of 51 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(2):191–8.

van Santen S, Roach RE, van Doorn R, et al. Clinical staging and prognostic factors in folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. JAMA Dermatol 2016;152(9):992–1000.

Klemke CD, Dippel E, Assaf C, et al. Follicular mycosis fungoides. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141(1):137–40.

Suchin KR, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Rook AH. Treatment of stage IA cutaneous T-cell lymphoma with topical application of the immune response modifier imiquimod. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(9):1137–9.

Dummer R, Urosevic M, Kempf W, et al. Imiquimod induces complete clearance of a PUVA-resistant plaque in mycosis fungoides. Dermatology. 2003;207(1):116–8.

Chong A, Loo WJ, Banney L, et al. Imiquimod 5% cream in the treatment of mycosis fungoides—a pilot study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15(2):118–9.

Deeths MJ, Chapman JT, Dellavalle RP, et al. Treatment of patch and plaque stage mycosis fungoides with imiquimod 5% cream. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(2):275–80.

Coors EA, Schuler G, Von Den Driesch P. Topical imiquimod as treatment for different kinds of cutaneous lymphoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16(4):391–3.

Chiam LY, Chan YC. Solitary plaque mycosis fungoides on the penis responding to topical imiquimod therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(3):560–2.

Martinez-Gonzalez MC, Verea-Hernando MM, Yebra-Pimentel MT, et al. Imiquimod in mycosis fungoides. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18(2):148–52.

Gordon MC, Sluzevich JC, Jambusaria-Pahlajani A. Clearance of folliculotropic and tumor mycosis fungoides with topical 5% imiquimod. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1(6):348–50.

Lewis DJ, Byekova YA, Emge DA, et al. Complete resolution of mycosis fungoides tumors with imiquimod 5% cream: a case series. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28(6):567–9.

Rook AH, Vowels BR, Jaworsky C, et al. The immunopathogenesis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Abnormal cytokine production by Sezary T cells. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129(4):486–9.

Rook AH, Kubin M, Cassin M, et al. IL-12 reverses cytokine and immune abnormalities in Sezary syndrome. J Immunol. 1995;154(3):1491–8.

Vowels BR, Rook AH, Cassin M, et al. Expression of interleukin-4 and interleukin-5 mRNA in developing cutaneous late-phase reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96(1):92–6.

Vowels BR, Lessin SR, Cassin M, et al. Th2 cytokine mRNA expression in skin in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103(5):669–73.

Sauder DN. Immunomodulatory and pharmacologic properties of imiquimod. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1 Pt 2):S6–11.

Urosevic M, Dummer R, Conrad C, et al. Disease-independent skin recruitment and activation of plasmacytoid predendritic cells following imiquimod treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(15):1143–53.

Suzuki H, Wang B, Shivji GM, et al. Imiquimod, a topical immune response modifier, induces migration of Langerhans cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114(1):135–41.

Shalabi D, Bistline A, Alpdogan O, et al. Immune evasion and current immunotherapy strategies in mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sezary syndrome (SS). Chin Clin Oncol. 2019;8(1):11.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patient for participation.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Doaa Shalabi, Nish Vadalia and Neda Nikbakht have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

While the institutional review board approval was not required for this single case study, the patient provided consent for publication of this report. Additional informed consent was obtained from all patients for whom identifying information is included in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9104903.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Shalabi, D., Vadalia, N. & Nikbakht, N. Revisiting Imiquimod for Treatment of Folliculotropic Mycosis Fungoides: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 9, 807–814 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-019-00317-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-019-00317-2