Abstract

Introduction

Atrophic scarring occurs throughout the course of inflammatory acne and across the spectrum of severity. This study evaluates perceptions of the general population toward individuals with clear skin and acne scars.

Methods

An online survey administered in the USA, UK, Japan, Germany, France and Brazil to respondents 18 years and over presented three facial pictures of clear skin or digitally superimposed acne scars (but no active acne lesions) in a random fashion. At least one clear and one scar picture were presented to each participant.

Results

Among the 4618 responders, 33% themselves had facial acne scars. The skin was the first thing noticed about the face by 41% when viewing pictures with scars vs 8% viewing clear skin (p < 0.05). Those with scars were less likely to be considered attractive (17% vs 25%), confident (25% vs 33%), happy (23% vs 30%), healthy (21% vs 31%) and successful (17% vs 24%), and more likely to be perceived as insecure (15% vs 8%) and shy (23% vs 14%) compared with those with clear skin (all p < 0.05). The significance of the responses obtained varied according to the acne and scar status of the respondent. Skin care was cited as the habit most in need of improvement by 59% vs 13% of respondents viewing pictures with scars vs clear skin, respectively (p < 0.05). All respondent subgroups cited skin care irrespective of their own acne and scar status (all p < 0.05 vs pictures with clear skin). Those with scars were thought less likely to have a promising future (78% vs 84%) than those with clear skin (p < 0.05). The majority of respondents reported willingness to pay money to eradicate scars.

Conclusion

The results of this multi-national survey demonstrate that facial acne scars are perceived negatively by society, confirming the importance of preventing acne scars with early treatment of inflammatory acne.

Funding

Galderma International S.A.S France.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acne is one of the most common skin diseases, affecting around 650 million of the world’s population [1]. It is a multifactorial disease encompassing comedones, papules, pustules, nodules and scars [2, 3]. Scarring can remain for life and therefore act as a prominent and visible reminder of the disease [3]. Atrophic acne scarring is more frequent than many individuals may realize, with at least 40% of active acne patients having scars [4].

Over the years, several different risk factors have been linked with scar development [5–7]. Recent data highlight that acne severity, time between acne onset and first effective treatment, and acne relapse after treatment are key factors related to scarring. Although scarring occurs most frequently in patients with severe or very severe acne, it is becoming increasingly apparent that scars can occur in patients with all severities of acne, including those who are almost clear or have mild acne [4]. Inflammation of the pilosebaceous follicle deep within the dermis is one of the main pathophysiological processes involved in acne scarring, with data showing that the type and magnitude of the inflammatory response is strongly linked with scar development [3, 5–7]. Other factors related to scar development include family history of acne, acne location and acne duration [4, 8, 9]. Acne scars are more common on the face than on the back and chest [8, 9]. The presence of clinically relevant scarring, defined as mild or greater, increases with acne duration and reaches a peak after a person has had acne for 2–3 years [9].

Acne can have a huge impact on a person’s quality of life. It can cause depression, which may result in impaired social functioning and suicidal ideation [10]. In addition, the social, psychological and emotional problems experienced by individuals with acne can be worse than those experienced by individuals with other limiting long-standing illnesses, such as asthma, epilepsy and arthritis [11].

Scarring is often the primary concern of a patient with acne [3]. It has been known for a long time that acne scarring can cause depression and is a risk factor for suicide [12]. More data are now beginning to emerge on the impact of acne scars, specifically on quality of life. Individuals want to hide or cover their scars and feel embarrassed, self-conscious and/or less self-confident. Scars are also a source of frustration, sadness, anger and/or anxiety. People who develop acne scars feel their appearance interferes with their professional relationships and chances of future employment [4]. The prevention of acne scars therefore needs to be viewed as a major goal in the treatment of inflammatory acne [7]. Early, aggressive and appropriate treatment of acne before scarring occurs is important, as it may effectively decrease the risk of acne scarring [2–5, 13].

As early as the 1970s, the impact of physical appearance ‘stereotypes’ on social desirability and future career prospects has been evaluated [14, 15]. More recently, numerous studies have shown that judgments and decisions are often negatively impacted by physical appearance, for example higher weight is associated with lower wages, attractiveness is an advantage when job applications are mediocre and high facial adiposity reduces the perceived leadership ability [16–19]. Dermatologists focused on acne from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne group hypothesized that the presence of acne scars would elicit negative impressions on other people’s perceptions of such individuals, which would also impact judgments made about them. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the perceptions of the general population aged 18 years and over to individuals with either clear skin or digitally superimposed acne scars, but no active acne lesions.

Methods

A survey was developed by members of the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne group (Online Appendix). The study was conducted between September 12 and September 18, 2012 using an email invitation followed by an online survey. Email addresses were obtained from individuals who had self-opted to participate in research surveys through a variety of sources. The survey was administered in six countries (USA, UK, Japan, Germany, France and Brazil) among respondents from the general population aged 18 years and over, identified from the large database of email addresses available. Quotas were set for demographic factors such as gender, region, ethnicity and age to ensure reliable and accurate representation of the entire population aged 18 and over in each country. All respondents took the survey in their native language.

As part of the survey, each respondent answered questions about facial pictures of men and women with either clear skin or digitally superimposed acne scars, but no active acne lesions (Fig. 1). A total of 12 images per country were used in the survey, comprising 50% male and 50% female with one clear and one scarred picture for six separate models. Each respondent was presented with three facial pictures in a random fashion, the only condition being that at least one clear and one scarred picture was presented to each participant. Respondents in each country saw a mix of ethnicities that represented the demographic of their nation. This design allowed the respondents to focus in-depth on specific visual stimuli and kept the survey at a reasonable length. Respondents also answered questions without seeing pictures, which included questions about their own experiences with acne and acne scars.

The data were processed using the Quantum software (Unicom Systems, Inc, Mission Hills, CA, USA) and T-tests run using a 95% confidence level/5% risk level. Only significant differences equal to or higher than the designated confidence level were reported.

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Experiences of Acne and Acne Scars Among Respondents

Responses were obtained from 4618 individuals (American: 1039; British: 714; Japanese: 701; German: 703; French: 736; Brazilian: 725) aged 18 years and over (ages 18–25: 15%; ages 26–35: 18%; ages 36–50: 30%; ages 51+: 38%). There was a similar distribution between male and female respondents (male: 49%; female: 51%).

A total of 13% of respondents presently had acne, 46% had acne previously and 41% never had acne. Among the subgroups who presently had acne or had acne previously, 29% had used prescription acne treatments (39% presently with acne vs 26% previously with acne, p < 0.05), 43% were never warned about scars that might result from their acne (34% presently with acne vs 46% previously with acne, p < 0.05) and 33% had current scars on the face as a direct result of their acne (58% presently with acne vs 25% previously with acne, p < 0.05). Approximately two-thirds (66%) of all respondents questioned from the UK and US (the only countries where this question was asked) would be more concerned about the way their face would look with scars resulting from acne, rather than the acne itself (34%).

First Impressions of Others

When provided with a list of facial features without seeing any pictures, 17% of respondents reported that they typically noticed a person’s skin first, compared with 60%, 11%, 8% and 4% for eyes, hair, mouth and nose, respectively. These results did not vary among those respondents presently with acne, previously with acne, with no acne presently/previously, with acne presently/previously without current acne scars or with acne presently/previously with current acne scars. Eyes were first noticed significantly more frequently among respondents previously with acne (60%) or with no acne presently/previously (62%) compared with respondents presently with acne (55%; both p < 0.05). Skin was first noticed significantly more frequently among respondents presently with acne (21%) compared with respondents previously with acne (17%) or with no acne presently/previously (16%; both p < 0.05). Respondents with acne presently/previously with current acne scars were less likely to notice the eyes (55% vs 61%; p < 0.05) and more likely to notice the skin (22% vs 16%; p < 0.05) compared with respondents with acne presently/previously without current acne scars.

When viewing the pictures presented, the proportion of respondents reporting the skin was the first thing they noticed about the person’s face increased to 25% and was significantly higher when viewing pictures of those with acne scars vs clear skin (p < 0.05, Fig. 2). When viewing pictures of those with acne scars, the results for eye, mouth and nose did not vary significantly among respondents presently with acne, previously with acne, with no acne presently/previously, with acne presently/previously without current acne scars or with acne presently/previously with current acne scars. Hair was first noticed significantly more frequently among respondents previously with acne (14%) or with no acne presently/previously (15%) compared with respondents presently with acne (11%; both p < 0.05). Among respondents presently with acne, skin was first noticed significantly more frequently (45%) compared with respondents previously with acne (41%) or with no acne presently/previously (41%; both p < 0.05). Respondents with acne presently/previously with current acne scars were less likely to notice the hair (11% vs 14%; p < 0.05) and more likely to notice the skin (44% vs 40%; p < 0.05) compared with respondents with acne presently/previously without current acne scars.

Emotional and Personal Attributes

In comparison to the pictures of those with clear skin, those with acne scars were less likely to be considered attractive, confident, happy, healthy and successful, and more likely to be perceived as insecure and shy (all p < 0.05; Table 1).

The significance of the responses obtained for these attributes varied according to the acne and scar status of the respondent (Table 2).

Just based on their appearance, respondents were less willing to be friends with acne scarred individuals than those with clear skin (62% vs 66%; p < 0.05). However, they were just as willing to introduce both groups to their close friends (24% vs 25%, respectively) and let them take care of their child/children (4% vs 3%, respectively).

Respondents felt the presence of scars would have a negative impact on an individual’s life. Those with acne scars compared to those with clear skin were perceived to be more likely to feel stressed (35% vs 26%, p < 0.05), to generally make people feel uncomfortable (30% vs 24%; p < 0.05) and to be unhappy with their life (31% vs 24%; p < 0.05). The presence of acne scarring was seen to have some impact on what individuals would be most likely to do on a typical weekend, with 17% vs 13% of respondents feeling that those with acne scars compared to those with clear skin would stay at home by themselves, respectively (p < 0.05).

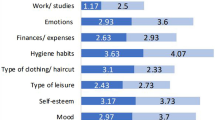

When asked which one habit (from a list provided) the individual in the picture most needed to improve, there was a 46% difference in the proportion of respondents citing skin care when viewing pictures of those with acne scars vs clear skin (59% vs 13%; p < 0.05). When viewing pictures of those with acne scars, skin care was the habit most commonly chosen to be in need of improvement (59%), whereas sleeping was most popular with clear skin at 34% (Fig. 3). Respondents with no acne presently/previously, acne presently/previously without current acne scars or acne presently/previously with current acne scars viewing pictures of those with acne scars all cited skin care as the habit most in need of improvement significantly more frequently than when viewing pictures of those with clear skin (Table 3).

Skill Set and Prospects

When provided with a list of skills, respondents were less likely to perceive those with acne scars as having skills in public speaking, sports, kissing, sex and singing (all p < 0.05, Table 4); the remainder of the skills were found not to be statistically significant. The responses obtained for these skills varied according to the acne and scar status of the respondent (Table 5). Those with scars were thought less likely to be hired for a job after a job interview (78% vs 82%; p < 0.05), to be seen as a good entrepreneur (19% vs 23%; p < 0.05) or to have a promising future (78% vs 84%; p < 0.05) than those with clear skin.

Cost Impact of Scars

Many respondents affected by acne scars reported willingness to pay at least some money to get rid of their scars forever (68% of Americans and 66% of Japanese) or to have their skin free from scars/blemishes (58% of Germans). In the UK, 71% of respondents felt acne scar sufferers would be willing to spend at least some money (an average of £1673) to permanently remove their scars. Similarly, a majority of French respondents (59%) and Brazilians (67%) would rather spend more money on products that would make their skin free from scars or blemishes than on high-end clothing or shoes.

Discussion

People often judge others and make decisions based on an individual’s physical appearance [14–19]. To our knowledge, this is the first in-depth, multi-national survey conducted to evaluate the perceptions of people (with or without acne) toward individuals with clear skin compared to those with acne scars (but no active acne lesions).

This study demonstrates that those with acne scars are perceived differently—with unfavorable attributes. Furthermore, the skin is more frequently the first facial feature noticed if an individual has acne scars vs clear skin. Taken together, the results of this survey suggest that observers infer that acne scars reflect neglectfulness of one’s health and skin care habits, as well as appearance. Interestingly, when viewing pictures with acne scars, skin care was still cited as the habit requiring most improvement irrespective of the acne and scar status of the respondent. Although individuals with acne scars believe that such scars have a negative impact on their own quality of life [4], it is worrying that other people may also judge them by the presence of such scars. This negative perception is likely to have a further impact on the burden of those with acne scars. Importantly, despite cultural differences, results were similar in all countries where the survey was carried out.

Parallels can be drawn with a previous study showing that judgments regarding personality based on physical appearance viewed through full-body photographs varied depending on posture, expression and pose [20]. More recent data highlight that facial features also impact first impressions, including approachability, youthful attractiveness and dominance to different degrees [21].

This study demonstrates that the presence of acne scars can have a negative impact on perceived skill set and future prospects. It is unclear whether people with acne scars encounter lesser social or occupational opportunities, but these results suggest that further research regarding such impediments may be of value.

Many adults have latent fears and insecurities about acne scars, as highlighted by the survey results showing that participants would be willing to pay money to rid themselves of scars forever. The survey questions on this topic differed slightly per country, in line with cultural expectations and currencies used.

A significant challenge for health-care professionals is that less than one-third (29%) of survey participants who had acne at some point in their life (either presently or previously) had used prescription acne treatments and almost half (43%) had never been warned about scars that might result from their acne. Since clinically relevant scarring increases with acne duration and a delay in starting appropriate treatment [4, 8, 9], it is important that everyone with acne is informed about the risk of scarring and is treated early and effectively to decrease this risk.

Although most respondents were more concerned about the way their face would look with scars resulting from acne rather than the acne itself, many had not used prescription acne treatments to help decrease the risk of such scars [2–5, 13]. There is a need to address this issue to gain insight into why individuals might not seek medical advice for the treatment of their acne. Since the treatment of scars remains difficult, many will have permanent scars. This persistence is another reason for informing individuals with acne and health-care professionals about scar prevention.

Parallels can be drawn between the results presented here and the data obtained in a study conducted by Ritvo et al. looking at the perceptions of teenagers with acne [22]. This study used similar methodology to the one used here and provided insights regarding the negative perception of others to individuals with acne.

The current survey has limitations because participants had to be willing to take part in the survey and able to complete it online. In addition, the survey does not address the long-term psychosocial effect of acne scarring. Further research is needed to evaluate data from different countries and ethnic groups to see if this has any impact on the results obtained. A recent publication demonstrated that 90.8% of Japanese acne patients have atrophic or hypertrophic acne scars, which have adversely impacted their quality of life [23].

The results obtained confirm the hypothesis from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne group regarding the negative perceptions surrounding acne scars and broaden our understanding of the potential impact of acne scars on an individual’s quality of life based on the perceptions of society. Increased education around risk factors associated with scar development and the long-term impact of scarring on both an individual with scars and those around them is warranted. Further consideration must also be given to the need for early and appropriate treatment to reduce the likelihood of acne scar development, so that acne patients are apprised of both the short- and long-term potential complications of acne.

Conclusion

This multi-national survey suggests that early treatment of primary acne lesions to decrease the risk of acne scarring is important in preventing acne scars, as they can be perceived negatively by society.

References

Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163–96.

Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: a report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(Suppl 1):S1–37.

Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(Suppl 5):S1–50.

Dréno B, Layton AM, Bettoli V, Torres Lozada V, Kang S on behalf of the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. Evaluation of the prevalence, risk factors, clinical characteristics, and burden of acne scars among active acne patients who have consulted a dermatologist in Brazil, France and the USA. In: Presented at: 23rd EADV Congress, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 8–12 October 2014;P024.

Goodman GJ. Management of post-acne scarring. What are the options for treatment? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:3–17.

Holland DB, Jeremy AH, Roberts SG, Seukeran DC, Layton AM, Cunliffe WJ. Inflammation in acne scarring: a comparison of the responses in lesions from patients prone and not prone to scar. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:72–81.

Kang S, Cho S, Chung JH, Hammerberg C, Fisher GJ, Voorhees JJ. Inflammation and extracellular matrix degradation mediated by activated transcription factors nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein-1 in inflammatory acne lesions in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1691–9.

Layton AM, Henderson CA, Cunliffe WJ. A clinical evaluation of acne scarring and its incidence. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:303–8.

Tan JK, Tang J, Fung K, et al. Development and validation of a Scale for Acne Scar Severity (SCAR-S) of the face and trunk. J Cutan Med Surg. 2010;14:156–60.

Halvorsen JA, Stern RS, Dalgard F, Thoresen M, Bjertness E, Lien L. Suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social impairment are increased in adolescents with acne: a population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:363–70.

Mallon E, Newton JN, Klassen A, Stewart-Brown SL, Ryan TJ, Finlay AY. The quality of life in acne: a comparison with general medical conditions using generic questionnaires. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:672–6.

Cotterill JA, Cunliffe WJ. Suicide in dermatological patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:246–50.

Layton AM. Optimal management of acne to prevent scarring and psychological sequelae. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:135–41.

Dion K, Berscheid E, Walster E. What is beautiful is good. J Person Soc Psychol. 1972;24:285–90.

Larkin JC, Pines HA. No fat persons need apply. Experimental studies of the overweight stereotype and hiring preference. Work Occup. 1979;6:312–27.

Cawley J. The impact of obesity on wages. J Hum Res. 2004;39:451–74.

Johnson SK, Podratz KE, Dipboye RL, Gibbons E. Physical attractiveness biases in ratings of employment suitability: tracking down the “beauty is beastly” effect. J Soc Psychol. 2010;150:301–18.

Re DE, Perrett DI. The effects of facial adiposity on attractiveness and perceived leadership ability. Q J Exp Psychol (Hove). 2014;67:676–86.

Watkins LM, Johnston L. Screening job applicants: the impact of physical attractiveness and application quality. Int J Select Assess. 2000;8:76–84.

Naumann LP, Vazire S, Rentfrow PJ, Gosling SD. Personality judgments based on physical appearance. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2009;35:1661–71.

Vernon RJ, Sutherland CA, Young AW, Hartley T. Modeling first impressions from highly variable facial images. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E3353–61.

Ritvo E, Del Rosso JQ, Stillman MA, La Riche C. Psychosocial judgements and perceptions of adolescents with acne vulgaris: a blinded, controlled comparison of adult and peer evaluations. Biopsychosoc Med. 2011;5:11.

Hayashi N, Miyachi Y, Kawashima M. Prevalence of scars and “mini-scars”, and their impact on quality of life in Japanese patients with acne. J Dermatol. 2015;42:690–6.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges were funded by Galderma International S.A.S France. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given final approval for the version to be published. Technical assistance with conducting the survey and analyzing the results obtained was provided by Kelton. Editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Lisa Swanson of Havas Life Medicom. Support for this assistance was funded by Galderma International S.A.S France.

Disclosures

Brigitte Dréno has served as a consultant, investigator or speaker for Galderma, Meda, Fabre and La Roche Posay. Jerry Tan has been an advisor, consultant, investigator and/or speaker for Allergan, Cipher, Dermira, Galderma, Pierre Fabre, Roche and Valeant. Sewon Kang has served as an advisory board member and investigator for Galderma. Maria José Rueda is a dermatologist and Medical Director Rx BU at Galderma Laboratories, L.P., Fort Worth, TX, USA. Vincente Torres Lozada has served as a consultant, investigator and speaker for Galderma. Vincenzo Bettoli has served as a consultant, investigator and speaker for GlaxoSmithKline, Difa Cooper, L’Oreal, Galderma, Biogena, Bioderma, Meda, Visupharma and Pierre-Fabre. Alison Layton served as an investigator, advisor, consultant and speaker for Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, MEDA, LeoPharma, Indentis, Valeant, Dermira, Pfizer, Novartis, Wyeth and L’Oreal.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

On behalf of the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. Brigitte Dréno, Jerry Tan, Sewon Kang, Vicente Torres Lozada, Vincenzo Bettoli and Alison M Layton are members of the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne.

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/94B4F0601CAA2319.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Dréno, B., Tan, J., Kang, S. et al. How People with Facial Acne Scars are Perceived in Society: an Online Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 6, 207–218 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-016-0113-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-016-0113-x