Abstract

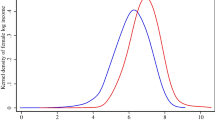

Mothers in the United States use a combination of employment, public transfers, and private safety nets to cushion the economic losses of romantic union dissolution, but changes in maternal labor force participation, government transfer programs, and private social networks may have altered the economic impact of union dissolution over time. Using nationally representative panels from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) from 1984 to 2007, we show that the economic consequences of divorce have declined since the 1980s owing to the growth in married women’s earnings and their receipt of child support and income from personal networks. In contrast, the economic consequences of cohabitation dissolution were modest in the 1980s but have worsened over time. Cohabiting mothers’ income losses associated with union dissolution now closely resemble those of divorced mothers. These trends imply that changes in marital stability have not contributed to rising income instability among families with children, but trends in the extent and economic costs of cohabitation have likely contributed to rising income instability for less-advantaged children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We exclude the 2008 panel of the SIPP because it covers the recession; an analysis of how the costs of union dissolution changed during the recession is important but beyond the scope of the current article, which focuses on long-term trends.

The trade-off is that each panel of the SIPP is relatively short, and we observe households for only several years (as opposed to decades), so we can assess only short-term economic consequences of union dissolution, not long-term consequences that might unfold decades after dissolution.

Thus, our sample does not include households with children who are not the children of the household reference person or his/her spouse, such as children of other adult relatives in the household. For households that contain two or more children at some point during the panel, we randomly select one child in the household so that the household is represented in the sample only once.

About one-half of households that experienced a dissolution were not observed for the full 12 months before and after the dissolution. As a robustness check, we also estimated our models with a balanced panel that included only households with observations for the full period. The results were statistically and substantively the same, so we retained the larger unbalanced panel for the analyses.

A growing number of children live in father-only families or in shared-custody arrangements, and it would be interesting to examine the economic consequences of dissolution for them as well. Unfortunately, their numbers in the SIPP are too small to provide reliable estimates of trends over time, so we exclude them from the analysis.

In a tiny fraction of cases (<2 %), more than one household member meets the POSSLQ criteria. In these cases, we select the POSSLQ person who was closest in age to the household reference person. Adjusted POSSLQ tends to overstate the extent of cohabitation because it counts romantic partners as well as opposite-sex roommates. However, because the extent of this overcounting has remained relatively constant over time (Casper and Cohen 2000), it will not bias our conclusions about trends over time. In supplemental analyses, we created an adjusted POSSLQ measure for the post-1996 panels as well; the results we present herein are robust to either the POSSLQ or the unmarried partner definition of cohabitation.

We do not rely on the retrospective date of divorce survey questions, for which the SIPP has been criticized because of high rates of imputation (Kennedy and Ruggles 2014); we observe the divorces as they happen.

Because there is no direct question about whether a cohabiting romantic relationship ended, cohabitation dissolution is inferred based on whether the person still lives in the household (not the romantic status of the relationship).

For a small sample of cases, we observe multiple marriages or cohabitations during a SIPP panel; for these cases, we include only the first observed marriage or cohabitation in our sample. We capture information about subsequent relationships and partners in our measures of postdissolution social network income.

The SIPP topcodes each income measure to preserve confidentiality; see Westat (2001: appendix B) for more information on specific topcode values for each measure.

If we do not observe a household for a full tax year prior to the first observation of a February, we estimate annual income based on the average monthly earned income during the portion of the year that we do observe them. Our approach assumes a 100 % take-up rate of the EITC, which overstates actual receipt, but take-up rates of the EITC are quite high—more than 80 %—relative to other transfer programs (Berube 2005).

Ideally, we would have liked to include the cash value of subsidized medical assistance from Medicaid and other sources, but the appropriate way to assign a cash value to medical benefits is hotly debated, with no agreed-upon convention (see, e.g., Wolfe 1998).

FMR rates are published by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) every calendar year and vary based on the number of bedrooms. We estimate the number of bedrooms for which a family is eligible using HUD guidelines for eligibility that are based on the number and sex of adult and child family members. FMR values are released for each metropolitan area, but the metropolitan locations of households are not publically available in the SIPP. The SIPP does report the state of residence, however; thus, we estimate a state-level FMR by calculating a population-weighted average FMR based on the FMRs and population sizes of all metropolitan areas in the state. In a small number of cases, the SIPP does not release the exact state of residence but groups several states into clusters for confidentiality purposes. In these cases, we construct an FMR for the state cluster rather than for an individual state. If the implicit cash value of the subsidy is negative (which occurs if 30 % of the household’s income is greater than the FMR), we assign the cash value of the subsidy to be 0.

In our sample, the estimated EITC and housing subsidies accounted for about 3.6 % of household income, on average, and 17.2 % of total government transfer income.

We identify the presence of a new partner either when a person identified as a spouse of the householder enters the household or when a person identified as an unmarried partner (post-1996) or as a POSSLQ (pre-1996) entered the household after the dissolution of the focal (i.e., first) union. This measure also includes income from former spouses/partners if the couple separates and later reunites. This occurs in only a small number of cases and is not sufficiently large to analyze as a separate category. About 4.4 % of married mothers had repartnered by 12 months after the dissolution (4.2 % in 1980s, 5.1 % in 1990s, and 3.2 % in 2000s). About 12.0 % of cohabiting mothers had repartnered by 12 months after the dissolution (9.3 % in 1980s, 11.6 % in 1990s, and 15.0 % in 2000s).

We do not know how resources are pooled among the adults who share a household, so we cannot determine exactly how the other adults pool their income with the householder and her children.

The decision to use a 12-month window before and after the dissolution is the result of a trade-off. The longer we require this window to be, the more cases we exclude because we observe the dissolution too soon or too late in the panel to observe 12 months on either side of it. If we require a shorter window, we can include more cases that meet the criteria, but we do not get as clear a sense of the time trend. Our sample sizes and the precision of our estimates change if we use a longer or shorter time window, but the substantive results are not sensitive to the decision to use a 12-month time frame and do not change if we use a balanced or an unbalanced panel.

We include household size as a control variable rather than using size-adjusted household income as the dependent variable because using a constructed ratio as a dependent variable in a regression analysis implies interactions between the ratio denominator and all the independent variables in the analysis (Smock 1993).

In supplemental analyses, we estimated separate equations for each SIPP panel and found that our conclusions about trends over time were not driven by any single panel.

After 500 repetitions, the standard error values did not change appreciably in different iterations, so we present results for bootstrapped standard errors estimated with 500 repetitions.

Many government transfer programs do not count cohabiting partners’ incomes (or they are not reported even if they should be), so many cohabiting mothers are eligible for cash or in-kind assistance in the form of the EITC, food stamps, and housing assistance, for example. Married mothers are less likely to qualify for such programs because husbands’ incomes are counted in benefit eligibility and are more likely to be reported; as a result, married women become eligible for cash transfer programs upon divorcing, and the expansion of government cash transfer programs, like the EITC, has made this more likely over time.

References

Amato, P. R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 1269–1287.

Andersson, G. (2002). Children’s experience of family disruption and family formation: Evidence from 16 FFS countries. Demographic Research, 7(article 7), 343–364. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2002.7.7

Avellar, S., & Smock, P. J. (2005). The economic consequences of the dissolution of cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 315–327.

Beck, R. W., & Beck, S. H. (1989). The incidence of extended households among middle-aged black and white women: Estimates from a 5-year panel study. Journal of Family Issues, 10, 147–168.

Berube, A. (2005). Earned Income Credit participation—What we (don’t) know. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Bianchi, S. M., & McArthur, E. (1991). Family disruption and economic hardship: The short-run picture for children. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Bianchi, S. M., Subaiya, L., & Kahn, J. R. (1999). The gender gap in the economic well-being of nonresident fathers and custodial mothers. Demography, 36, 195–203.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2007). Changes in the labor supply behavior of married women: 1980–2000. Journal of Labor Economics, 25, 393–438.

Bramlett, M. D., & Mosher, W. D. (2002). Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States (Vital and Health Statistics, Series 23). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Bumpass, L., & Lu, H.-H. (2000). Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies, 54, 29–41.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2013). Women in the labor force: A databook (BLS Report No. 1049). Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Cancian, M., & Meyer, D. R. (1996). Changing policy, changing practice: Mothers’ incomes and child support orders. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 618–627.

Casper, L., & Cohen, P. (2000). How does POSSLQ measure up? Historical estimates of cohabitation. Demography, 37, 237–245.

Cohen, P. N., & Bianchi, S. M. (1999). Marriage, children, and women’s employment: What do we know? Monthly Labor Review, 122(12), 22–31.

Daly, M., & Burkhauser, R. V. (2003). The Supplemental Security Income Program. In P. Moffitt (Ed.), Means-tested transfer programs in the United States (pp. 79–140). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Desai, S., Chase-Lansdale, P. L., & Michael, R. T. (1989). Mother or market? Effects of maternal employment on the intellectual ability of 4-year-old children. Demography, 26, 545–561.

Duncan, G. J., & Hoffman, S. D. (1985). A reconsideration of the economic consequences of marital dissolution. Demography, 22, 485–497.

Dye, J. (2008). Participation of mothers in government assistance programs: 2004 (Current Population Reports, P70–116). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Edin, K., & Lein, L. (1997). Making ends meet: How single mothers survive welfare and low-wage work. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Feenberg, D., & Coutts, E. (1993). An introduction to the TAXSIM model. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 12, 189–194.

Freeman, R., & Waldfogel, J. (2001). Dunning delinquent dads: The effect of child support enforcement policy on child support receipt by never married women. Journal of Human Resources, 36, 207–225.

Galarneau, D., & Sturrock, J. (1997). Family income after separation. Perspectives on Labour and Income, 9(2), 18–28.

Garfinkel, I., Huang, C.-C., McLanahan, S. S., & Gaylin, D. S. (2003). The roles of child support enforcement and welfare in non-marital childbearing. Journal of Population Economics, 16, 55–70.

Goldstein, J. (1999). The leveling of divorce in the United States. Demography, 36, 409–414.

Harknett, K. (2006). The relationship between private safety nets and economic outcomes among single mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 172–191.

Henly, J. R. (2002). Informal support networks and the maintenance of low-wage jobs. In F. Munger (Ed.), Laboring below the line: The new ethnography of poverty, low-wage work, and survival in the global economy (pp. 179–203). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Henly, J. R., Danziger, S. K., & Offer, S. (2005). The contribution of social support to the material well-being of low-income families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 122–140.

Hoffman, S. (1977). Marital instability and the economic status of women. Demography, 14, 67–76.

Holden, K. C., & Smock, P. J. (1991). The economic costs of marital dissolution: Why do women bear a disproportionate cost? Annual Review of Sociology, 17, 51–78.

Hotz, V. J., & Scholz, J. K. (2003). The Earned Income Tax Credit. In P. Moffitt (Ed.), Means-tested transfer programs in the United States (pp. 141–198). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Jayakody, R. (1998). Race differences in intergenerational financial assistance: The needs of children and the resources of parents. Journal of Family Issues, 19, 508–533.

Johnson, P. D., Renwick, T., & Short, K. (2010). Estimating the value of federal housing assistance for the supplemental poverty measure (SEHSD Working Paper #2010-13). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Kennedy, S., & Bumpass, L. L. (2011, March–April). Cohabitation and trends in the structure and stability of children’s family lives. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Washington, DC.

Kennedy, S., & Ruggles, S. (2014). Breaking up is hard to count: The rise of divorce in the United States, 1980–2010. Demography, 51, 587–598.

Kenney, C. (2004). Cohabiting couple, filing jointly? Resource pooling and U.S. poverty policies. Family Relations, 53, 237–247.

Kenworthy, L., & Smeeding, T. (2013). Growing inequalities and their impacts in the United States (GINI Project). Retrieved from http://www.gini-research.org

Killewald, A., & Bearak, J. (2014). Is the motherhood penalty larger for low-wage women? A comment on quantile regression. American Sociological Review, 79, 350–357.

Koenker, R. (2005). Quantile regression. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

LaLumia, S. (2013). The EITC, tax refunds, and unemployment spells. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 5, 188–221.

Marr, C., Charite, J., & Huang, C.-C. (2013). Earned Income Tax Credit promotes work, encourages children’s success at school, research finds. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved from http://www.cbpp.org/files/6-26-12tax.pdf

McKeever, M., & Wolfinger, N. H. (2001). Reexamining the economic costs of marital disruption for women. Social Science Quarterly, 82, 202–217.

McKeever, M., & Wolfinger, N. H. (2005). Shifting fortunes in a changing economy: Trends in the economic well-being of divorced women. In L. Kowaleski-Jones & N. H. Wolfinger (Eds.), Fragile families and the marriage agenda (pp. 127–157). New York, NY: Springer.

McLanahan, S. (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41, 607–627.

McLanahan, S., & Percheski, C. (2008). Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 257–276.

McLanahan, S., Tach, L., & Schneider, D. (2013). The causal effects of father absence. Annual Review of Sociology, 39, 399–427.

McManus, P. A., & DiPrete, T. A. (2001). Losers and winners: The financial consequences of separation and divorce for men. American Sociological Review, 66, 246–268.

Moffitt, R., Ribar, D., & Wilhelm, M. (1998). The decline of welfare benefits in the US: The role of wage inequality. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2227–2258.

Mooney, C. Z., & Duval, R. D. (1993). Bootstrapping: A nonparametric approach to statistical inference. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Morrison, D. R., & Ritualo, A. (2000). Routes to children’s economic recovery after divorce: Are cohabitation and remarriage equivalent? American Sociological Review, 65, 560–580.

Mott, F. L., & Moore, S. F. (1978). The causes and consequences of marital breakdown. In F. L. Mott (Ed.), Women, work, and family (pp. 113–135). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Musick, K., & Michelmore, K. (2012, May). Change in the stability of marital and cohabiting unions following the birth of a child. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, San Francisco, CA.

Mykyta, L., & Macartney, S. (2011). The effects of recession on household composition: “Doubling up” and economic well-being (Social, Economic, and Household Statistics Division Working Paper 2011-04). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Nestel, G., Mercier, J., & Shaw, L. B. (1983). Economic consequences of midlife change in marital status. In L. Shaw (Ed.), Unplanned careers: The working lives of middle-aged women (pp. 109–125). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Parrott, S., & Sherman, A. (2006). TANF at 10: Program results are more mixed than often understood (CBPP report). Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved from http://www.cbpp.org/8-17-06tanf.htm

Pavetti, L. D., Finch, I., & Schott, L. (2013). TANF emerging from the downturn a weaker safety net. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Peterson, R. R. (1989). Women, work, and divorce. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Peterson, R. R. (1996). A re-evaluation of the economic consequences of divorce. American Sociological Review, 61, 528–536.

Raley, R. K., & Bumpass, L. (2003). The topography of the divorce plateau: Level and trends in union stability in the United States after 1980. Demographic Research, 8(article 8), 245–260. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2003.8.8

Roschelle, A. R. (1997). No more kin: Exploring race, class, and gender in family networks. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Schoen, R., & Canudas-Romo, V. (2006). Timing effects on divorce: 20th century experience in the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 749–758.

Seltzer, J. A. (1994). Consequences of marital disruption for children. Annual Review of Sociology, 20, 235–266.

Smock, P. J. (1993). The economic costs of marital disruption for young women over the past two decades. Demography, 30, 353–371.

Smock, P. J. (1994). Gender and the short-run economic consequences of marital disruption. Social Forces, 73, 243–262.

Smock, P. J. (2000). Cohabitation in the United States: An appraisal of research themes, findings, and implications. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 1–20.

Smock, P. J., Manning, W. D., & Gupta, S. (1999). The effect of marriage and divorce on women’s economic well-being. American Sociological Review, 64, 794–812.

Stack, C. B. (1974). All our kin: Strategies for survival in a black community. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Stirling, K. J. (1989). Women who remain divorced: The long-term consequences. Social Science Quarterly, 70, 549–561.

Teachman, J., & Paasch, K. (1994). Financial impact of divorce on children and their families. Future of Children, 4(1), 63–83.

Wamhoff, S., & Wiseman, M. (2006). The TANF/SSI connection. Retrieved from http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v66n4/v66n4p21.html

Weiss, R. S. (1984). The impact of marital dissolution on income and consumption in single-parent households. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 46, 115–127.

Weitzman, L. J. (1985). The divorce revolution. New York, NY: Free Press.

Westat. (2001). Survey of Income and Program Participation user’s guide (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/programs-surveys/sipp/methodology/SIPP_USERS_Guide_Third_Edition_2001.pdf

Western, B., Bloome, D., Sosnaud, B., & Tach, L. (2012). Economic insecurity and social stratification. Annual Review of Sociology, 38, 341–359.

Wolfe, B. (1998). Incorporating health care needs into a measure of poverty: An exploratory proposal. Focus, 19(2), 29–31.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Melissa Giangrande and Jessica Powers for superb research assistance, and Lonnie Berger, Marcia Carlson, Rebecca Glauber, Robert Haveman, Daniel Meyer, Rebecca Ryan, Christine Schwartz, Tim Smeeding, and participants at the Institute for Research on Poverty’s Emerging Scholars Conference and the Cornell Inequality Discussion Group for feedback on early drafts of the article. The research was supported by the President’s Council of Cornell Women Affinito-Stewart Grants Program and by Grant No. AE00102 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), which was awarded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of ASPE or SAMHSA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

ᅟ

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tach, L.M., Eads, A. Trends in the Economic Consequences of Marital and Cohabitation Dissolution in the United States. Demography 52, 401–432 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0374-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0374-5