Abstract

Combinatorial approaches comprised of combinatorial magnetron co-sputtering deposition and fast screening methods are introduced to study color as a function of composition in Au-based alloys. The microstructures of the thin films and bulk alloys are identified by X-ray diffraction, and their colors of the alloys are characterized by optical reflectivity. The results reveal that when comparing microstructures and reflectivity, thin films are similar to bulk alloys. In Au-Ag-Cu solid solutions, the color of the ternary alloy follows the rule of mixture. For colors resulting from AuAl2 intermetallic, the color of an alloy scales with the percentage of the intermetallic phase and the deviation from its ideal binary composition. In the Au-Al-Cu library, we found a ∼90 % AuAl2 area fraction compositional window where copper addition can be tuned to improve mechanical properties while keeping purple color, even though Al and CuAl2 phases exist. Moreover, when comparing the color in Au-Cu-Si-Ag amorphous and crystalline state solid solution for the same composition, the colors are essentially identical.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Color is ubiquitous and plays an important role in our daily life [1]. Although there are various mechanisms underlying the generation of color, for gold(Au) and copper(Cu), it is their electron configurations that are responsible for the significant variation in absorption and reflection of light over the visible part of the spectrum. This leads to their yellow and red appearance [1]. Because of their unique colors compared with other metals, gold and its alloys have been used dating back to early human civilizations for decoration, jewelry, dentistry, and a wide variety of tools [2]. Since gold is soft, other elements, such as copper, silver, and nickel, are added to improve mechanical properties. However, the addition of alloying elements into gold also results in variation of color, depending on how the electron configuration changes with composition. Dramatic changes in color as a function of composition exist in systems which form intermetallic phases, such as gold(Au)-aluminum(Al). In order to improve their workability, variable of additions into Au–Al binary system are developed, such as cobalt, nickel, palladium, and copper [3]. For instance, the Au-Al-Cu system exhibits a wide range of colors, including reddish, yellow, apricot, silver, and pink, among which the pink color mainly originates from the formation of purple AuAl2 phase [4, 5]. AuAl2 is the most thermally stable phase in this system and mechanically brittle [2, 6]. This unique color of AuAl2 is due to the interband transitions between the valence and the conduction bands, leading to a dip in the reflectivity spectrum at ∼2.2 eV, corresponding to a wavelength of 563 nm [7–9]. Because of this green light absorption, the combination of reflected blue and red light of higher energy results in the intense purple hue exhibited by AuAl2. In addition, the low energy bulk plasma frequency may also contribute to the purple color of AuAl2 [10]. Au-based alloys also exist in an amorphous form [11–14]. These metallic glasses have been discovered in Au-Si and extended to more practical Au-Ag-Pd-Cu-Si alloys [15]. For Au-Ag-Pd-Cu-Si alloys, the color and variation of color with composition have been studied by measuring yellowness index after tarnishing [15]. Such tarnishing mechanism lies in the internal oxidation. Therefore, whether color change happens upon crystallization without oxidation is not known.

Despite the wide use of some colored Au alloys, a systematical investigation on the change of color with composition and thus phase formation is essential to gain a fundamental understanding of the color-microstructure relationship and therefore better control over these properties. Conventionally, the investigation of colored gold alloys relies on the sequential casting technique [4, 5], which is extremely slow and also discontinuous.

In the present study, we use magnetron co-sputtering to create compositional libraries that represent large fractions of the phase space with a continuous compositional gradient [12, 16, 17]. The material libraries can be categorized into three different groups based on phases formed: solid solution, intermetallics, and amorphous state. We explore how color varies with composition and phase formation by using systematic compositional, structural, and optical mappings, which reveal the dominant factors controlling the color of the alloys.

Experimental

Figure 1 illustrates our experimental strategy to study color in gold-based alloys. We use magnetron co-sputtered deposition to create material libraries in the form of films. A fully automated energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) mapping technique was used to quantify the compositional spread of the libraries. The structure and phase formation were characterized by using rapid scanning X-ray diffraction (XRD) mapping. We measured the reflectivity of the library within the visible spectrum to quantitatively characterize their color. To summarize the colors in a standardized manner, we converted the reflectivity data into coordinates for the chromaticity diagram.

Schematic of experimental strategy to study the effect of chemical composition on color. a Magnetron co-sputter deposition from three 2-in targets which are placed in a tetrahedral symmetry to create composition gradients on a 4-in silicon substrate. b This results in continuous compositional libraries which are typically annealed to reveal the color. c High-throughput scanning XRD characterization on the library is used to determine the structures and involved phases. d The determination of the chemical composition is carried out through high-throughput automated EDX measurement which are summarized in Gibbs triangles. e Reflectivity measurement are carried out at numerous locations on the library within visible spectrum range, 380–780 nm, to quantify the color of an alloy. f Results from the reflectivity data are represented as coordinates on the chromaticity diagram

The continuous libraries were deposited on silicon substrates using magnetron co-sputter deposition from elemental targets. The three targets were placed in a tetrahedral configuration to result in compositional gradient across the substrate. The composition gradient of the library was tuned by varying the substrate-to-target orientation. The base pressure before sputtering was below 10−7 mTorr. The thickness of the film libraries were ∼200 and ∼600 nm which were controlled by deposition time based on the deposition rate measured using a quartz thickness monitor. Since sputtering causes defects in the structure, the as-sputtered films were subsequently annealed at 330 °C for 10 min to reduce defects and hence to reveal color (Fig. 2), the same parameters as Furrer et al. [18]. The thin film library composition was compared to the bulk samples. These bulk alloys were prepared by melting elements with purities better than 99.99 % in an arc melter under Ar atmosphere.

The composition of the alloys in the library was identified by EDX mapping using an Oxford EDS system with their X-Max 80 mm2 detector and INCA software. The grid spacing is 4 mm for EDS measurement. Structural characterization was conducted by using scanning XRD with a Cu Kα radiation source. The spacing between XRD scanning measurements was 2 mm. Morphologies were observed using a Zeiss SIGMA variable pressure scanning electron microscope (SEM).

To quantify the color of the libraries, reflectivity with a wavelength range from 345 to 790 nm was measured using a microreflectance setup equipped with a commercial silver reflector for calibration. Since color perception is highly subjective, CIE 1931 XYZ color space was used to quantitatively define the color differences of the alloys [19]. The reflectivity over visible light range (380 to 780 nm) was chosen to calculate the coordinates in the chromaticity diagram.

Results and discussions

Color of solid solution

The appearance of Au-Ag-Cu alloys with composition ranging from 30 % (all compositions are in atomic percentage) to 90 % for gold, 6 to 62 % for silver, and 3 to 30 % for copper, respectively, is presented in Fig. 3. As confirmed by XRD, all alloys are fcc solid solutions. Compared to the color of Au-rich alloys in the library, the color of Cu-rich alloys is reddish (Fig. 3c). This is illustrated in the shift of the plasma frequency to high wavelength, absorbing the green color component. The color of Ag-rich alloys appears white or colorless due to the higher reflectance of shorter wavelengths. Since the reflectivity spectrum of Ag-rich alloys (Au30.7Ag61.7Cu7.6) is comparable to that of pure silver, alloys with a Ag content exceeding 62 % bleach the Au–Cu color on the thin film. As summarized in the chromaticity diagram (Fig. 3d), the colors within this AuAgCu library are essentially yellow. The variation in color within this system which is comprised only of solid solutions is determined by the color of their constituents and can be essentially predicted by the weighted average of the color of their constituents, namely the rule of mixture of optical constants, refractive index n, and absorption coefficient k [20].

Au-Ag-Cu compositional spread and reflectivity measured on Cu-rich, Ag-rich, and Au-rich on thin film, characterized in chromaticity diagram. a Sputtered Au-Ag-Cu library on 4-in silicon substrate. b In Au-Ag-Cu library, gold composition varies between 30.4 and 90.0 %, silver between 6.0 and 61.7 %, and copper between 2.6 and 29.7 %. c Reflectivity of Cu-rich, Ag-rich, and Au-rich on thin film, compared with that of the corresponding pure elements. d Chromaticity coordinates of Au-rich, Ag-rich, Cu-rich part, and Au65.6Ag 25.7Cu8.7 which locates at the center on AuAgCu library marked in chromaticity diagram and their location and composition marked in Fig. 3a, b, respectively

Color of intermetallics

Figure 4a shows the library appearance and microstructures of the intermetallics forming Au-Al-Cu system. A color line with bright and intense purple hue follows the composition line of aluminum of 70∼75 at%, and another short color line follows the composition line of gold of 30∼35 at% and copper of less than 5 %. Compositions on both these two color lines are marked as pink data points, serving as a practical composition library for jewelry manufacture. In order to rule out film thickness effects on the color, we fabricate Au-Cu-Al thin films with ∼200 and ∼600 nm thickness. No recognizable difference in color was observed between films of different thickness, indicating that the color originates from intrinsic material property. Figure 4 summarizes the SEM images, composition, XRD spectrum, and reflectance spectrum for four points along the color transition direction, respectively. The selected compositions are Au12.4Cu7.4Al80.2, Au14.4Cu8.4Al77.2, Au16.5Cu9.3Al74.2, and Au18.7Cu10.6Al70.7.

Microstructures, compositions, XRD spectrum, and reflectance spectrum for Au12.4Cu7.4Al80.2, Au14.4Cu8.4Al77.2, Au16.5Cu9.3Al74.2, and Au18.7Cu10.6Al70.7, respectively. The compositions are chosen at equidistantly alloys along the color transition in the copper rich part of the film. a Physical locations of the selected points and their microstructures. b Composition range covered in the library and colored compositions marked as pink dots. c XRD spectrum of the selected alloys. d Reflectance spectrum of the selected alloys

The four selected compositions are marked at their corresponding positions on the thin film library. The color along this compositional line gradually changes from colorless to light purple. From the perspective of the reflectance spectrum, the addition of Au causes a reflectance decrease in the short and mid-wavelength range, resulting in a light purple and pink hue. This results in the shift of the minimum which moves to lower wavelength from 598 to 545 nm, corresponding to 2.3 eV in energy. This value is close to the dip in reflectivity at 2.2 eV in AuAl2. The XRD spectrum (Fig. 4c) reveals that the Al phase disappears with increasing Au.

A detailed microstructure investigation is shown in Fig. 5 where more alloy compositions are studied along this highly colored gradient line. AuAl2 phase percentage drops from 100 % to eventually under ∼10 % with increasing Al% constituents (Fig. 5a), while the overall alloy appears silver as the distance of the CIE coordinates approaching white point (Fig. 5c). For alloys identified in the 100 % AuAl2 phase region, the peak shifts of (2,2,0) and (3,1,1) planes, for examples, result from the solubility of Cu into Au (Fig. 5b).

AuAl2 phase percentage change, peak shifts for crystal planes, and color transition along highly colored gradient line (Fig. 4a) with composition transection of increasing Al% but decreasing Au% and Cu%. a The corresponding AuAl2 phase percentage drops from 100 % to under ∼10 % with increasing percent Al. b For alloys identified as 100 % AuAl2 phase region, the peak shifts of (2,2,0) and (3,1,1) planes as examples are shown with decreasing to lower degrees as increasing Cu% constituent, indicating a solid solution of Cu into Au. c Distance of CIE coordinates to white point of several corresponding alloys compared to that of bulk AuAl2 alloy

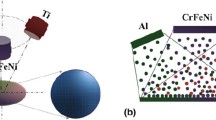

In order to evaluate if this combinatorial method can be used to draw conclusion about the bulk alloys, we compared the microstructure (Fig. 6a, b) and reflectance spectrum (Fig. 6c) for the selected composition of Au23.7Cu3.0Al73.3 in bulk and thin film. Although the bulk sample exhibits a different microstructural morphology from that of film (Fig. 6a), the dominant phase is AuAl2 in both bulk and film (Fig. 6b). According to EDS measurement, AuAl2 is the bright phase in the bulk sample (upper panel in Fig. 6a), while the darker one is a mixture of CuAl2 and Al phase (Fig. 6a). The different length scales in the microstructures of bulk and film samples originate from the different cooling rates, growth mechanisms, and growth direction. Despite these different microstructural morphologies, the reflectivity spectrum of the bulk and thin film samples are essentially identical, as shown in Fig. 6c. The calculated coordinates in chromaticity diagram indicates that these two data points locate so close in chromaticity diagram that the color variation between bulk and thin film samples is negligible. This indicates that the color of the alloys is determined by the stoichiometry-driven phase formation; the influence of their morphologies is also negligible. Therefore, the thin films can predict the color of bulk samples.

Comparisons of microstructures and reflectivity between thin film and bulk samples with same composition. a Microstructures of bulk form Au23.7Cu3.0Al73.3 (top) compared with that of the same composition on the thin film (bottom). b XRD spectrum of bulk form and thin film. c Reflectivity spectrum of Au23.7Cu3.0Al73.3 of bulk form and thin film. The calculated coordinates in the chromaticity diagram are listed

Furthermore, we fabricated bulk samples of five compositions chosen from the library along the line of high color gradient at Au–Al rich part (Fig. 7a). Their SEM images on the right column reveal that the shape of the AuAl2 phase ranged from dendritic to circular. Figure 7b illustrates the correlation between AuAl2 fractions in the SEM image and the constituent element percentage for each bulk samples. The fraction AuAl2 first increases and then decreases with the increasing Au and Al ratio. At Au29.3Cu3.2Al67.5, where the ratio of Au over Al approximates the AuAl2 phase, the AuAl2 phase has the highest area phase fraction. In this case, AuAl2 and other phases present together following the rule of mixture, meaning that the intensity of purple hue relies on the fraction of the purple phase. Here, both Au29.3Cu3.2Al67.5 and Au36.4Cu3.5Al60.1 exist a high AuAl2 area fraction over ∼90 % and define a compositional window where Cu addition can be tuned to improve mechanical properties while keeping purple color.

Microstructures of Au-Cu-Al bulk samples and their corresponding AuAl2 phase area fraction. a Arc-melted bulk alloys prepared with the same compositions along the highly color gradient line on the film (left) and their SEM images (right). b AuAl2 phase area fraction for each composition. (To determine the area fraction of AuAl2 phase in SEM images, ImageJ was used as an analyzing software.)

By measuring the reflectance spectrum of the prepared Au-Cu-Al bulk samples, we calculate and express their colors in a chromaticity diagram, as shown in Fig. 8. All alloys are located in the purple range. Because the saturation of the color can be described as the distance to the white point, AuAl2 is the most saturated. Au29.3Cu3.2Al67.5 is the most saturated in the ternary library, which is in agreement with our previous observation that the highest AuAl2 area percentage in Au29.3Cu3.2Al67.5 results in the most purple color of the alloys.

Color of amorphous alloys

Amorphous metals exhibit superior mechanical properties including high strength, hardness, elastic strain limit, corrosion resistance, and thermal plastic forming capability [21]. Due to this combination of properties and processibility, they are promising materials for applications [22]. However, whether the amorphous metals will undergo a color change upon crystallization is not well understood. Revealing that the possible color difference of amorphous and crystalline phases is important, a possible appearance change might limit their applications originated from the customers’ aesthetic preferences.

Figure 9a, b display the appearance of Au-Cu-Si-Ag amorphous and crystalline films with identical composition ranges. The amorphous phase forming region is presented in Fig. 9a, b. Intuitively, the color is essentially the same for amorphous film (Fig. 9a) and crystalline film (Fig. 9b), indicating that the crystallization has a negligible effect on color for this library. To quantitatively reveal how the color of amorphous alloys varies with crystalline, we measured the reflectivity of three compositions in both amorphous and crystalline states. As shown in Fig. 9c, the reflectivity of the chosen amorphous alloys is nearly the same as that of crystallized ones. Furthermore, the coordinates of the amorphous alloys on the chromaticity diagram are close to those crystalline alloys, suggesting that the color difference is indistinguishable to the naked eye.

Au-Cu-Si-Ag 4-in films with same composition range sputtered on silicon substrate. a As-deposit continuous film. b Films with patches to prevent diffusion upon melting. This film was fully melted and then solidified. XRD was scanned to prove that the film was fully crystallized. c Reflectivity comparison of the same composition both on the amorphous region on as-deposit film and crystallized film. Their chromaticity diagram coordinates are also listed in corresponding color

These observations are not surprising, because the amorphous state is similar to disordered solid solution. For the current Au-Cu-Si-Ag system, the primary crystalline phases are solid solutions as well. As showed in the preceding section, the color of solid solution follows the rule of mixture, e.g., the color is a mixture of the constitute elements. Therefore, for the Au-Cu-Si-Ag alloy system, the color difference of amorphous state from crystalline state is minor proved by the similar chromaticity diagram coordinates.

Typically, processing and shaping of amorphous alloys are carried out taking advantage of their unique thermoplastic processability [23–25]. However, in this process, amorphous alloys may transform into crystalline state, especially when processing is conducted by temperature ramping to get maximum deformation [26]. Our finding that the color difference between amorphous and crystalline state is indistinguishable (Fig. 9) is encouraging, because the desired color can be reserved after processing and one is relieved from one constrain from the perspective of material selection.

Conclusions

We used combinatorial methods to study color as a function of composition in Au-based alloys. When comparing microstructures and reflectivity, thin films are similar to bulk alloys. In Au-Ag-Cu solid solutions, the color of this ternary alloy follows the rule of mixture; it is determined by the weighted average of the colors of its elements. For colors resulting from intermetallics, the alloy color scales with the phase percentage of the intermetallic phase. In the Au-Al-Cu library, we found a ∼90 % AuAl2 area fraction compositional window where Cu addition can be tuned to improve mechanical properties while keeping purple color. Moreover, the color in amorphous and crystalline state for same composition is essentially the same.

References

Nassau K (1987) The 15th causes of color—the physics and chemistry of color. Color Res Appl 12(1):4–26. doi:10.1002/col.5080120105

Cretu C, van der Lingen E (1999) Coloured gold alloys. Gold Bull 32(4):115–126

Corti CW (2004) Blue, black and purple: the special colours of gold. Proc Santa Fe Symposium Met-Chem Research Inc 121–133

Bhatia VK, Levey FC, Kealley CS, Dowd A, Cortie MB (2009) The aluminium-copper-gold ternary system. Gold Bull 42(3):201–208

Levey FC, Cortie MB, Cornish LA (2002) Hardness and colour trends along the 76 wt.% Au (18.2 carat) line of the Au-Cu-Al system. Script Mater 47(2):95–100. doi:10.1016/S1359-6462(02)00100-8

Supansomboon S, Maaroof A, Cortie MB (2008) “Purple glory”: the optical properties and technology of AuAl2 coatings. Gold Bull 41(4):296–304

Chen LY, Lynch DW (1988) The optical properties of Aual2 and Ptal2. Phys Status Solidi B 148(1):387–394. doi:10.1002/pssb.2221480136

HSU L-S (1994) Physical properties of AuAl2, AuGa2, AuIn2, and PtGa2. Modern Physics Letters B 08(21n22):1297–1318. doi: 10.1142/S0217984994001278

Fox M (2010) Optical properties of solids. Oxford master series in condensed matter physics, vol 3, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Keast VJ, Birt K, Koch CT, Supansomboon S, Cortie MB (2011) The role of plasmons and interband transitions in the color of AuAl2, AuIn2, and AuGa2. Appl Phys Lett 99(11). doi: 10.1063/1.3638061

Klement W, Willens RH, Duwez P (1960) Non-crystalline structure in solidified gold-silicon alloys. Nature 187(4740):869–870. doi:10.1038/187869b0

Ding SY, Gregoire J, Vlassak JJ, Schroers J (2012) Solidification of Au-Cu-Si alloys investigated by a combinatorial approach. J Appl Phys 111(11). doi: 10.1063/1.4722996

Schroers J, Lohwongwatana B, Johnson WL, Peker A (2005) Gold based bulk metallic glass. Appl Phys Lett 87(6). doi: 10.1063/1.2008374

Guo H, Zhang W, Chen MW, Saotome Y, Fukuhara M, Inoue A (2011) Effect of Au content on thermal stability and mechanical properties of Au-Cu-Ag-Si bulk metallic glasses. Metall Mater Trans A 42A(6):1486–1490. doi:10.1007/s11661-010-0584-9

Eisenbart M, Klotz UE, Busch R, Gallino I (2014) A colourimetric and microstructural study of the tarnishing of gold-based bulk metallic glasses. Corros Sci 85:258–269. doi:10.1016/j.corsci.2014.04.024

Ding SY, Liu YH, Li YL, Liu Z, Sohn S, Walker FJ, Schroers J (2014) Combinatorial development of bulk metallic glasses. Nat Mater 13(5):494–500. doi:10.1038/Nmat3939

Thienhaus S, Naujoks D, Pfetzing-Micklich J, Konig D, Ludwig A (2014) Rapid Identification of areas of interest in thin film materials libraries by combining electrical, optical, X-ray diffraction, and mechanical high-throughput measurements: a case study for the system Ni-Al. ACS Comb Sci 16(12):686–694. doi:10.1021/Co5000757

Furrer A, Seita M, Spolenak R (2013) The effects of defects in purple AuAl2 thin films. Acta Mater 61(8):2874–2883. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2013.01.029

E308-13 A (2013) Standard practice for computing the colors of objects by using the CIE System. American Society for Testing and Materials, West Conshohocken, PA 1–43

Shiraishi T, Tilley RD (2014) An estimation of the reflectivity of some monophasic binary gold alloys. Gold Bull 47(1–2):75–82. doi:10.1007/s13404-013-0124-7

Kumar G, Tang HX, Schroers J (2009) Nanomoulding with amorphous metals. Nature 457(7231):868–872. doi:10.1038/Nature07718

Schroers J, Nguyen T, O’Keeffe S, Desai A (2007) Thermoplastic forming of bulk metallic glass—applications for MEMS and microstructure fabrication. Mat Sci Eng a-Struct 449:898–902. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2006.02.398

Li N, Xu XN, Zheng ZZ, Liu L (2014) Enhanced formability of a Zr-based bulk metallic glass in a supercooled liquid state by vibrational loading. Acta Mater 65:400–411. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2013.11.009

Li N, Chen Y, Jiang MQ, Li DJ, He JJ, Wu Y, Liu L (2013) A thermoplastic forming map of a Zr-based bulk metallic glass. Acta Mater 61(6):1921–1931. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2012.12.013

Liu Z, Schroers J (2015) General nanomoulding with bulk metallic glasses. Nanotechnology 26(14). doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/26/14/145301

Schroers J (2008) On the formability of bulk metallic glass in its supercooled liquid state. Acta Mater 56(3):471–478. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2007.10.008

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support from National Science Foundation (NSF) under grant no. MRSEC DMR 1119826 (CRISP). We also thank Professor Jung Han for generously providing us microreflectance setup and Cheng Zhang for training. We also thank Professor Hui Cao for informative discussion on characterization of optical properties of thin films and for providing spectrophotometer setup.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Liu, Y., Gong, P. et al. Combinatorial exploration of color in gold-based alloys. Gold Bull 48, 111–118 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13404-015-0167-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13404-015-0167-z