Abstract

A fairly simple yet efficient quantitative protocol was developed to investigate plant composition using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), through biomass analysis arising from the whole shoot system of Cardoon (Cynara cardunculus L.), Cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.) and Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.). An analytical compositional report of the biomasses, serving as a standard method to identify the different chemical groups present, was compared with relevant FTIR spectra and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) thermographs. In order to interpret the highly convoluted absorption spectra, not only a series of reference materials were examined but also extraction protocols were implemented to sequentially isolate the compositional units allowing a spectroscopic monitoring of their progressive removal from the biomass. This approach enabled the assignment and distinction of a series of vibrational peaks and regions identified in the lower wavenumber region. These peaks/regions, were found to be capable of quantitating different chemical units, such as lignin, fats and lipids, even in the case of structural polysaccharides, like cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin, which are the primary constituents of plant cells. Fats and lipids were easily detected at the 3050–2800 cm−1 region, with their concentration determined by the isolated 720 cm−1 and the 728 cm−1 peaks, when present. Lignin concentration was determined via the 1508 cm−1 peak. Hemicellulose is contributing to the 1640, 1245 cm−1 as well as the 1740 cm−1 peak, with its concentration determined in the 850–750 cm−1 region. Cellulose content was quantified via the 895 cm−1 peak, while pectin appeared at the 915 cm−1 peak and also contributed to the 1640 cm−1 signal. Consequently, a better understanding of the vibrational convolution could thus be achieved when studying plant cells where multiple structural units contribute to the spectra. It is therefore expected that plant cellular composition can be adequately revealed with a single FTIR spectrum, without the need for intensive analysis methods, offering a faster and more efficient approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Plant biomass is emerging as a key resource in biotechnology for the production of renewable energy and high added-value chemicals. The abundancy and renewability of this biomass seems to be a great alternative to the depleting and harmful for the environment traditional fossil fuels, as well as their derivatives. By that, a wide variety of biomass is now being utilized as a starting point for the production of biodiesel and bioethanol [1]; nanocellulose is also emerging as a promising biobased reinforcing nanomaterial [2, 3]. Pectin (a polysaccharide based on galacturonic acid) and other polysaccharides comprising hemicellulose, such as xylan or mannan-based polymers, have attracted attention regarding their use in the food industry and even in packaging applications [4,5,6,7]. The main and most crucial factor determining the efficiency of these biotechnological processes is the composition of the biomasses itself, that is, the different chemical constituents of the cells and their concentration. Therefore, a deep understanding of biomass composition is of significant importance for any bioprocess commercialization.

The majority of wet analytical methods for the determination of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin that are standardized by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) or the Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry (TAPPI) rely on destructive extraction followed by isolation. Even though these methods are typical and of high precision, they are destructive, labor-intensive, expensive, and require the use of hazardous chemicals that generate a large amount of waste. Thus, novel procedures that offer fast, yet comparable, accuracy are constantly in pursuit.

A fast, efficient but also environmentally friendly alternative is presented in the current work by using high resolution analytical instruments. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), combined with standard deconvolution techniques, can quantitatively analyze complex mixtures because of the distinct thermal decomposition temperatures of each component. In that manner, the pyrolytic decomposition in inert atmospheres occurs at lower temperatures for the biomasses comprised of hemicellulose (250–300 °C) then by cellulose (300–350 °C) and finally by lignin (300–500 °C) [8]. As a result, calculations on these three components have been previously attained [9, 10]. However, the irregular pyrolytic behavior of these structural units, coupled with the overlapping of thermal events in these temperature regions, requires delicate/precise fittings using multiple pseudo components, which may lead to inaccuracies if not properly performed.

The study of biomaterials using infrared spectroscopy has also been a great alternative to the traditional wet chemistry methods [11]. Near Infrared Reflectance (NIR), provides a certified technique for compositional analysis and derivation of nutritional value of plant materials, such as crude fat, protein, carbohydrate and crude fibers [12,13,14]. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) is another well-established characterization technique based on the absorption in the Mid Infrared Region (MIR). By embedding the materials into salt matrices that do not absorb infrared radiation (such as NaCl or KBr), absorbance, transmittance or reflectance spectra can be acquired. Using direct contact accessory, reflected evanescent wave (ATR) can be collected, even with micro-setup configurations [15, 16]. The former method (IR) provides better and more representative spectra but requires the analyte to be in powder or a thin film form. In contrast, the latter method (ATR) allows materials to be measured directly as received/obtained. Till now, relevant studies have been previously attempted using the above techniques to determine the constitution and structural arrangement of wood or plant biomass [17, 18], foodstuff [19] and even biological entities [20]. In fact, multivariate analysis and software packages, have enabled highly accurate predictions of lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose using FTIR [21, 22]. However, biomass fibrous structures are more complex and many other structural units exist, which are crucial for plant viability and of significant value to humans as well, such as pectic polysaccharides, fats – lipids and proteins. These components often exhibit overlapping absorption bands as well vibrational couplings making identification and quantification of related species particularly difficult. To address this, a detailed and comprehensive examination of the entire FTIR spectrum is proposed in the current study which includes spectral regions that were not examined before. Generally, extraction protocols are employed to isolate specific components within the biomass [17, 23,24,25,26] and FTIR analysis of these extracts provides further verification, as repeating units of these structural entities can vary significantly. By identifying these spectral regions and analyzing their absorbance, quantitative predictions of various structural units of the plant biomasses were achieved using FTIR.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Raw, reference materials and chemicals used

A two-year (2021–2022) field experiment was conducted to investigate the effects of different cultivation practices on three lignocellulosic crops (Cynara cardunculus L., Panicum virgatum L., Cannabis sativa L.) that produce high biomass yield, in a typical Mediterranean soil and climate. The agricultural practices followed, regardless of the cultivation, involved assessing the impact of irrigation—specifically, comparing reduced irrigation levels to full irrigation concerning evapotranspiration—and varying nitrogen fertilization rates. These practices were analyzed to identify the optimal cultivation conditions that maximize crop yield while minimizing production costs. This research was conducted at the experimental farm of the University of Thessaly, located in Thessaly plain of Greece (coordinates: 39°30′45″ N, 22°28′03.1″ E, altitude 170 m).

During the harvest sampling, the plants were promptly weighed in the field, and a sub-sample was collected for subsequent laboratory analysis. These sub-samples were then placed in a hot air dryer set to a temperature of ≤ 59 °C until they achieved a stable weight, corresponding to a dry weight with a moisture content of 4–5%, to guarantee accurate measurements.

Microcrystalline Cellulose and Alkali treated Lignin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, while Wheat Arabinoxylan (Medium Viscosity) was purchased from Megazyme. Citrus Peel pectin was also used in this study, with its extraction procedure described earlier [27]. Finally, for the progressive extraction methodology, chloroform (CHCl3, HPLC grade) was acquired from Thermo Fisher Scientific, methanol (MeOH, HPLC grade) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, ACS reagent grade) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, while hydrochloric acid (HCl, Analytical reagent grade), potassium chloride (KCl, ACS reagent grade), phosphoric acid (H3PO4, ACS reagent grade) and citric acid (Citr. Ac., ACS reagent grade) were sourced from Fluka. All chemicals were used as received.

2.2 Analytical methods of biomass composition

After air drying the biomass at a temperature of ≤ 59 °C, the dried samples, which included the complete plant comprising stems, leaves, flowers, and seeds, were processed by crushing and chopping them for laboratory analysis. Each plant (Cynara cardunculus L., Panicum virgatum L. and Cannabis sativa L.) was analyzed separately as individual sample.

To quantify fat/lipid content, the different pre-weighed dry biomasses (~ 3.0 g) were treated for at least 6 h within a Soxhlet apparatus with 200 ml n-hexane as organic solvent. Hexane is mainly used due to its low cost, efficiency, and recyclability [28] A similar study utilised hexane as solvent for fats/lipids extraction on lignocellulosic biomass such as Cannabis [29]. Pectin content was determined as galacturonic acid equivalents (GalA) according to the m-hydroxydiphenyl method of Melton and Smith [30].

Cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin were quantified using the analytical protocols of Sluiter et al. [31] after the extraction of water- and ethanol-soluble components within a Soxhlet apparatus. Briefly, 300 mg of extractives-free (water- and ethanol-soluble components) biomass was treated with 3.0 mL 72% (w/w) H2SO4 for 1 h at 30 °C. The acid was then diluted to 4% (w/w) by adding 84 g of deionized water and the mixture underwent a second hydrolysis step at 121 °C for 1 h. To estimate sugar losses caused by degradation during the second hydrolysis, standard solutions of glucose, xylose, arabinose, mannose, and galactose were used. The hydrolyzed samples were vacuum filtered, and both solid and liquid fractions were analysed. To simplify the design process, in this wet chemical analysis it was assumed that hemicellulose does not contain any glucan. Therefore, in this context, hemicellulose was defined as the total of xylan, arabinan, galactan, and mannan while cellulose was defined as glucan [32]. It should be noted here however, that 4-o-methyl glucuronic acid, (a constituent of eudicots’ hemicellulose that will be discussed later) during the acid hydrolysis could be demethylated and decarboxylated [33] to some extent and contribute to glucan. In the current study, these phenomena are omitted. The amounts of cellulose and hemicellulose were ultimately calculated using correction factors of 0.90 for hexoses and 0.88 for pentoses. Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen method was used for protein content of approximately 0.5 g of biomass (weighted with an accuracy of four decimal places) using the factor 6.25 for all substrates. Soluble sugars composition was determined following three consecutive aqueous extractions (1:10 w/v) and characterised using a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). The recovery step was conducted at 40 °C in a 2-h duration under continuous agitation (180 rpm) on a hotplate stirrer (Witeg Labortechnik GmbH, Germany). The HPLC system was equipped with a Shodex SP0810 column and an RI detector (Shimadzu, Japan). The mobile phase was HPLC grade water at 0.5 mL/min flow rate, whereas the temperature of the column was set at 65 °C. Ash content was determined by placing 1.0 g of the dried biomasses on pre-weighed porcelain crucibles in a muffle furnace at 575 °C for a 6 h.

All analyses were performed in triplicate, and results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Analysis of variance and Pearson’s linear correlation (95% confidence interval) were performed using Statgraphics (Statgraphics Technologies, Inc., the Plains, VA, USA) to determine statistically significant differences between the biomasses’ composition.

2.3 Extraction protocols sequence performed in the biomasses

To support and highlight the capability of the analytical methods, extraction protocols were implemented to favor as much as possible the isolation of by-products and their consequent vibrational-infrared identification; relevant flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

2.3.1 DF treatment

For the extraction of fat and lipid tissue, 2.5 g of each different plant biomass (S1) was submerged in a mixture of chloroform/methanol (CHCl3/MeOH 1:1 v/v) with a liquid to solid ratio of 15/1. The mixture was vortexed for 5 min at 1600 rpm and left in the fridge overnight. Next, the biomass was filtered out using a Whatman filter paper and washed with ethanol (S3). The filtrate was mixed with 1 M KCl and 0.2 M H3PO4 to create a phase separation (as described in [34]). Afterwards, the bottom organic phase (chloroform) was isolated by pipetting and the fat-lipid tissue was extracted by evaporation of the solvent (S2). Acetic acid was not used, despite being indicated in [34], to avoid additional removal of the structural polysaccharides that would thus be promoted.

Afterwards, two separated extraction/removal protocols for hemicellulose and pectin, respectively, were conducted to the remaining mass of each plant’s DF treated biomass (fats and lipids free) solid residue (S3).

2.3.2 Hemicellulose extraction via LHCR1 and LHCR2 treatments

An alkaline hydrolysis step was applied to DF treated biomass solid residue in order to break the hydrogen bonds associated with cellulose and the covalent linkage with lignin [35]. In this context, part of the DF treated biomass was poured into an alkaline NaOH (10% w/v) solution at 50/1 (liquid/solid ratio) and stirred at 300 rpm for 2 h at 50 °C (LHCR1 treatment). This temperature (of 50 °C) is lower to the typical cooking temperature conditions (of 80 °C) and it was thus selected in order to avoid extra deacetylation on the afterwards obtained hemicellulose and generally to slow down the hydrolysis reaction.

The pulped biomass was then separated from the filtrate using a glass fiber filter. The filtrate was adjusted to a pH of 5 with 6 M HCl, followed by the addition of three volumes of ethanol and was left overnight for the precipitation of hemicellulose (LHC1/S4). The biomass residue was thoroughly washed with triple distilled water (TDW) until the pulp was no longer blackish but retained a yellowish color; it was then oven dried at 50 °C, grinded again and a sample was collected for analysis (S5). For possible additional progress of alkaline hydrolysis, the same methodology was further applied to the previously (LHCR1) hydrolyzed (yellowish) biomass using the same NaOH concentration, L/S ratio, mixing and temperature, but this time for 3 h (LHCR2 treatment). The same washing and grinding procedures were applied to the collected biomass after this step and a sample was collected as well (S7). The overnight precipitated hemicellulose from LCHR2, along with the one from LHCR1, were filtered using a 5-μm PVDF membrane filter (Millipore, Merck), washed with 70% ethanol and oven-dried (S6).

2.3.3 Pectin extraction via PCTR treatment

It is typically conducted under acidic conditions and at higher temperatures in order to hydrolyze protopectin (the insoluble polysaccharide present in plant cells). As is commonly known, mineral or organic acids effectively prove to facilitate hydrolysis and subsequent solubilization of pectin polysaccharides [7]. Therefore, the acid hydrolysis was performed on another part of the DF treated biomass using citric acid (C = 2 g/L, 10.4 mM) at pH = 2 for 2 h at 50 °C (PCTR treatment). After filtration with a glass fiber filter, three volumes of ethanol were poured into the filtrate so as to precipitate pectin that was filtered out, washed with 70% ethanol and oven-dried (S8). The remaining biomass residue was washed with TDW and ethanol, then dried, grinded and a sample was collected for analysis (S9).

2.4 Biomass and extracts characterization

All infrared spectra were recorded on a FTIR spectrophotometer Alpha II (Bruker Optics GmbH Ettinger, Germany). Samples were prepared by mixing 5 mg of analyte (grinded by a 400 W multiblender) and 100 mg of ground KBr and pressing them in a die, forming a pellet. Two or three pellets were prepared for each sample for replication. Background spectrum was collected each time with a pure KBr pellet while spectral acquisition with a resolution of 2 cm−1 and 64 scans was conducted. ATR spectra with the same experimental conditions (i.e., resolution: 2 cm−1 scans: 64) were also acquired for the isolated fats-lipids, when a pellet could not be formed. Regarding the data treatment, the noted baseline removal methodology in the FTIR spectra was performed with an Origin software (Origin2023Sr0H). During this, baseline points at 940, 850, 750 and 650 cm−1 were selected in the lower wavenumber region (940–650 cm−1) connected with the B-spline function.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) of the selected biomasses, and the reference materials were carried out by recording their mass loss using a TGA 55 (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). Samples were placed in platinum crucible and the pyrolysis experiments were performed from 25 to 700 °C with 10 °C/min heating rate under Nitrogen atmosphere (N5.0 N2 purity and of 25 mL/min). TRIOS software (TA Instruments) was used to obtain the temperature derivatives of mass loss (DTG) graphs for further component evaluation. Lastly, data analysis, peak fittings, deconvolutions and baselines were performed also with the Origin software.

1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Ascend 600 (Bruker BioSpin GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) spectrometer operating at a 1H Larmor frequency of 600.13 MHz. The studied samples (10 mg) were properly dissolved in 1 mL of D2O (Deutero GmbH) and were heated at 50 °C. The spectra were collected at 25 °C temperature. Spectral integration, phase and baseline corrections were performed using TopSpin 3.6.5 (Bruker BioSpin GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Differentiation of chemical units composing the biomass

3.1.1 Chemical analysis of the different biomasses

The chemical analysis of the different biomasses studied is presented in Table 1. Switchgrass, Cannabis and Cardoon were rich in cellulose (33.4%, 45.5% and 35.1%), hemicellulose (29.2%, 17.5% and 18.6%), and lignin (12.2, 9.3 and 9.7%), while the main component of hemicellulose was xylan (85.3, 53.1 and 68.3% of hemicellulose), following by mannan (9.9, 27.4, 19.9% of hemicellulose). The composition of soluble sugars and ash was 2.7, 1.9 and 0.7% and 3.2, 5.9 and 3.5%, respectively. Switchgrass composition is similar to that reported in the literature. However, the composition of the crop is closely related to the crop variety and especially to the cultivation conditions such as harvest time [36]. The composition of Cannabis is strongly connected with the different parts of the plants (flowers, seeds and stalks) [37]. In the present work, Cannabis was rich in protein (10.4%) and fat/lipids (5.8%) due to the present of seeds in the studied biomass. Cardoon was rich in lignocellulosic fraction and bioactive compounds such as pectin. Pectic polysaccharides constitute a large fraction of the Cardoon biomass (i.e. > 20%) and they are widely considered as a high value product from such crops [38, 39].

3.1.2 The three main components (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin)

To validate the above chemical analysis, thermogravimetric measurements were performed on the materials of the plant biomasses and are presented in Fig. 2a. The pyrolytic decomposition of hemicellulose occurs in the thermal range of 225–275 °C, while that of cellulose is between 275 and 350 °C. Lignin decomposes over a wider temperature range exhibiting a maximum at a higher temperature. The region at lower temperatures, between 150 and 225 °C, is mainly attributed to other (so indicated) structural components, such as fats–lipids and pectin polysaccharides, whose thermal response appears to overlap, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1.

After their removal-separation from the original biomasses, a clearer image of the three main components emerges as is depicted in Fig. 2b of DF-treated biomasses. The hemicellulose content is different in the three DF-treated biomasses being the lowest for Cannabis, relatively higher for Cardoon and even higher for Switchgrass. Additionally, the lignin is comparable across the samples, supporting the chemical analyses. Calculation-wise, after DF treatment, a three phase modeled remaining biomass is assumed as lignin, hemicellulose and cellulose remain. In fact, a large portion of pectin is also subtracted in the chloroform/methanol organic phase as it will be shown later. Based on Table 1, by normalizing to their sum both the phases’ concentrations (i.e. lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose) and the TGA Weibull fittings, a correlation graph is created with the findings mentioned above presented in Supplementary Fig. 2.

3.1.3 Extractives and the progressive chemical isolation of the different cellular components

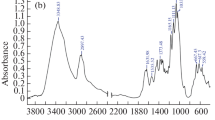

A typical FTIR spectrum of a biological entity displays heavy convolution and is generally difficult to interpret, mostly due to the various structural entities and plant cells. However, chemical methods for the subsequent removal of each component could in fact alleviate this problem, while revealing a more comprehensible spectrum. Series of such spectra are presented in Fig. 3 for the Cannabis plant biomass.

In this context, after acquiring FTIR spectra of the air-dried biomass (S1), the DF treatment was performed, and spectrum of the collected sample (S3) was subsequently measured. Spectral differences are mainly observed in the high wavenumber region (Region I, 3050–2800 cm−1), where CH stretching peaks are mainly absorbing. This type of chemical bonds that appear on the aliphatic lipid structures are absent in the spectrum of DF treated biomass and assert their successful removal. Additionally, the peak at 720 cm−1 in the insert graph (of S1), could be also attributed to such aliphatic (lipid) units. In Switchgrass, the extracted lipids similarly displayed a pertinent peak at 728 cm−1 peak that is then also removed from the biomass spectra (Supplementary Fig. 3). In the isolation protocol, after the phase separation, the proteins were confined to a middle layer and hinted to their supplementary extraction from the biomass solubilized in the CHCl3/MeOH mixture. Their removal is evident from the lower absorbance in the 1550 cm−1 area of all DF treated samples, which is associated with vibrational modes related to proteins.

Subsequently, hemicellulose extraction protocols, namely LHCR1 and LHCR2, were performed on the previously defatted samples. The main findings are that the whole 1800–1550 cm−1 spectral region (Region II) is mostly associated with the structural hemicellulosic polymers. This comes by the fact that, in the dark grey spectra (S5), when compared to the DF light orange sample (S3), the peaks at 1740 and 1245 cm−1 are completely absent, while 1640 cm−1 also decreases. Α peak at 1740 cm−1 is associated to ester bonds and is attributed to acetylated groups present in (hemicellulosic) xylan containing biomass. The disappearance of the other peak (1245 cm−1, Region III) is more perplexed as neither S5 (LHCR1) nor S7 (LHCR2) show this peak but it is present (thought at reduced intensity) in hemicellulose isolated S4 (LHC1) and the one extracted in the second protocol S6 (LHC2), as shown in Fig. 4. That is oddly also the case with the ester carbonyl peak (1740 cm−1) which is present in both extracted hemicellulose but it disappears completely from the biomass in LHCR1 protocol (S3). Additionally, during LHCR1 (S3) and LHCR2 (S5), there is a progressive decrease in IR absorbance in the 850 to 750 cm−1 (Region IV), as shown on the insert. This suggests that these peaks are, in fact, hemicellulose-based and decrease in parallel with the peak at 1640 cm−1. After the subsequent removal protocols, it is then reasonable to observe that the LHCR2 (S5) spectra resemble those of Alkali Lignin and Microcrystalline cellulose. This progressive extraction methodology was also implemented to the other two plant biomasses and the results are presented in the Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5.

The FTIR spectra of LHC1 and LHC2 hemicelluloses (also shown on Fig. 4) suggest that, in fact, xylan-based polymers are isolated as evidenced by their close resemblance with wheat extracted arabinoxylan, which serves as a reference material. The 1043 cm−1 vibrational peak is assigned to C–OH stretching of xylose containing polymers [40] while the 1740 cm−1 is a sign of acetyl groups forming ester bonds [41]. These data suggest that LHCR treatments at 50 °C can effectively preserve the acetyl groups in plant extracted hemicelluloses.

3.1.4 The case of pectin

Fruits and vegetables are commonly studied with IR techniques to investigate their high pectin content; however, literature regarding its direct observation in vegetative biomasses is scarce because only in some of them is it, as pectic polysaccharides, in a noticeable concentration.

In order to reveal any FTIR absorbance contribution correlated to pectin, the DF and PCTR protocols were applied to the Cardoon biomass (Fig. 5), that is, the one with the most significant pectin content according to the chemical analyzes (Table 1). Relevant spectral evidence should be marginally present in the FTIR spectrum of Switchgrass and not at all in that of Cannabis due to its low concentration there, as again noted by the chemical analyzes. Following DF treatment, an intensity reduction was observed not only in the high wavenumber lipid region (3050–2850 cm−1) but also in the Region II (1800–1550 cm−1), particularly in the 1640 cm−1 peak, with a greater extent in the Cardoon biomass relative to the corresponding of Switchgrass and particularly that of Cannabis. However, due to the high IR absorbance convolution contributed by many components, no strong conclusions can be drawn regarding pectin’s contribution via spectral region II. However, significant differences were observed at lower wavenumbers (Region IV 935–650 cm−1), with the peak at 915 cm−1 being almost if not completely absent in Switchgrass and certainly absent in the IR spectrum of Cannabis (Fig. 8). After the PCTR treatment (pectin extraction, S9), this peak disappeared (Fig. 5 and inset) and pectic polysaccharides were isolated (corresponding absorbance spectra are shown in Fig. 6 and inset), indicating that this peak could potentially serve as a marker for pectin determination. It is also worth mentioning that the pectin concentration decreases during the DF protocols, as shown in the FTIR spectra in Fig. 5 and inset, and its release should be monitored when its isolation is of concern.

Further investigation was also conducted regarding the state of the pectic polysaccharides within the biomass and the degree of esterification (DoE) of the isolated products. As shown in Fig. 6 in Region II, the 915 cm−1 peak found in the biomass spectra is also evident in both highly esterified pectin (citrus peel pectin) and the isolated pectin from Cardoon (PCT/S8).

From the pectin spectra, it is also evident that the absorbance drop in the 1700–1550 cm−1 region of the Cardoon biomass is associated with the low degree of esterification extracted PCT. The DoE of both isolated pectins was calculated according to Chatzigakis et al. [42]. Their study proved that the absorbance ratio of 1740 cm−1 peak divided by the sum of 1740 and 1640 cm−1 peaks, is proportional to the DoE by using reference materials and their blends. While examining Region I, the DoE values obtained from this method were 17% for Cardoon extracted pectin and 49% for Citrus peel pectin. Both values were in accordance with literature data for Cardoon [43, 44] and Citrus extracted pectins [45].

3.2 Understanding the biomass FTIR spectra

The correct succession and monitoring with FTIR of the above extraction protocols can give the possibility of optimal assignment and identification of spectral characteristics of individual components obtained from the plant biomass. In this context, Fig. 7 presents the spectra acquired from the three starting biomasses (S1) along with some references for clarification, divided in regions.

It is obvious that Region I (3050–2700 cm−1) is primarily associated to the fats and lipids content (may also contain waxes and cutin), with peaks at 2950, 2919 and 2849 cm−1 corresponding to CH3 and CH2 stretching vibrations, while the peak at 3010 cm−1 peak is attributed to = C-H from unsaturated fatty acid derivatives [46]. A small peak at 3005 cm−1, also attributed to the same groups, is also found in lignin though its concentration is much lower compared to woody biomasses. In Region II (1800–1480 cm−1), four distinct peaks can be clearly noted at 1740, 1640, 1550 and 1508 cm−1. The 1740 cm−1 peak is attributed to the ester groups found mainly on the intact esterified hemicellulose [47] as well as in the fats and lipids triglycerides and phospholipids, as mentioned earlier. The peak at 1640 cm−1 is related to bound water [48]; however, other components of the plant biomasses contribute to its high absorbance with the predominance of hemicellulosic and pectic polysaccharides due to their COOH or COO− stretching groups found in uronic acids (i.e., glucuronic, galacturonic acid, etc.) [49]. Lignin also contributes to the 1630 cm−1 peak through the C = C stretching vibrations of the unsaturated bonds; lignin however, is clearly identified via the distinct 1508 cm−1 peak, which originates from the skeletal vibration of the aromatic group [50]. Finally, hints of proteins can be traced in the plant biomasses by the 1545 cm−1 amide II peak. In Region III (1200–1300 cm−1), the progressive alkali treatment showed that the 1250 cm−1 peak is associated with hemicellulosic polysaccharides as no equivalent is found in the spectrum on pure cellulose, while also the peak did not change even after the mild acidic treatment. This broad peak has been previously assigned to C-O and O–H stretching vibrations found on polysaccharides [22]; present data however suggest that the peak may originate from a hemicellulose to lignin ether bonding as supported by another group [51] or from the partially eliminated acetyl groups [52]. Finally, in Region IV (650–950 cm−1), the peak found on pectin containing biomass at 915 cm−1 was shown to be present in both the extracted pectic polysaccharides and in the cases of low and high esterification. Calculated vibrational spectra of pectin via DFT in partially and fully esterified pectin smaller derivatives proposed [53] that the 915 cm−1 peak of interest arises from the C–C stretching vibration regarding the C–C linkage between the sugar and the carboxylic acid group or a stretching C-O vibration probably in the acid group. Both seem reasonable to be mainly found in a galacturonic acid based polymer. The 895 cm−1 peak is typical of cellulose and is mainly assigned as C–O–C β—glycosidic linkage [26, 54]; simulated spectra also suggested some contribution from the bending of the sixth carbon (exocyclic C6-OH) forming a methanol branch [55, 56]. Absorbance bands found on the 850–750 cm−1 region of the biomass, with intensity comparable to that of 895 cm−1 may be arising from interchain and intrachain covalent linkages in the structural hemicellulose (branching substitutions of xylan). This hypothesis derives from the fact that these bonds are breaking during the alkali hydrolysis, to permit the extraction of hemicellulose, and also as shown earlier in Fig. 3 this vibrational band (i.e. 850–750 cm−1) decreases in intensity after LHCR1 and LHCR2 protocols. More discussion on this band will be performed below. Lignin presents also two peaks of similar absorbance at 855 and 815 cm−1; however, their contribution in the plant spectra is visibly minimal. Lastly, the 720 cm−1 peak is also a characteristic CH2 rocking vibrational mode found on lipids and fats [46]. The main findings noted above are concentrated in following Table 2.

3.3 Quantitative methodology on composition based on FTIR

After the above tentative assignment of the spectral characteristics of the components of plant biomasses, a methodology for the quantification of their concentration is proposed below. Peaks for each component for which there was no overlap were first selected. After baseline correction of the spectra in the low wavenumber region, Gaussian fittings were applied for lignin at the 1508 cm−1 peak, pectin at 915 cm−1, cellulose at 895 cm−1, fats and lipids at 720 cm−1 and 728 cm−1 when detectable, while for hemicellulose the whole 850–750 cm−1 region was integrated. These fittings are illustrated in Fig. 8. Afterward, the normalized concentrations \({({\varvec{T}}}_{{\varvec{x}}})\) of each component were divided by the normalized fitted areas of their respective peaks/regions \({({\varvec{A}}}_{{\varvec{x}}})\) (area of a specific fitted peak divided by the sum of all the areas fitted for each component) to create a component calibration constant \({({\varvec{C}}}_{{\varvec{x}}})\). The average value of these three (one for each plant) along with its standard deviation can be found in Table 3. The standard deviation values were also normalized to the average value resulting in a scale of 100%, with all the constants’ divergences below 25% indicating a reasonable accuracy in predicting biomass composition.

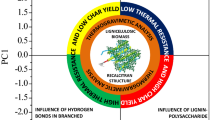

3.4 Identification of the different substitutions in hemicellulose of the biomasses arising from the IR and NMR characterization of different hemicellulosic (xylan) extracts

Based on the significant spectral differences (absorption bands in the 750–850 cm−1 window of Fig. 8) of the original biomasses in terms of the hemicellulose content of the Switchgrass versus Cardoon and cannabis, an attempt was made to further investigate the hemicellulosic substitutions, now exploiting their LHC1 xylan extracts (S4), via 1H NMR and FTIR.

1H NMR spectra were acquired from the extracted LHC1 xylan extracts of all the plants studied alongside the commercial Wheat Arabinoxylan (ArXLN) and are presented in Fig. 9A. The LHC1 spectrum of Switchgrass resembled that of ArXln regarding the 5.38, 5.28 and 5.21 ppm (A1) peaks occurring from the anomeric proton of arabinosyl units (Ara) that substitute (branch) xylan only at O- 3 and at the O- 2 and O- 3 positions respectively [57]. Other noticeable peaks that relate to these substitutions are the 4.26 ppm (A4) and 4.15 ppm (A2). It is worth mentioning that the odd peak at 5.53 ppm (A1) originates from an extra xylosyl unit linked to the O- 2 position in the arabinose branch, as enzymatic treatments in Switchgrass oligosaccharides have previously shown [58]. From the other side, Cardoon and Cannabis LHC1 s both contained the anomeric 5.28 ppm (4MG1) and the 3.45 ppm (OCH) peak found in 4-O-methyl glucuronic acid units (4MG) in O- 2 substituted xylans [59], while O- 3 arabinosyl linkages were scarse. For molar quantification, the 3.28 ppm (X2) of unsubstituted xylan was integrated along with the anomeric protons of both Ara and 4MG, with the results for the various plants’ xylans presented in Table 4. Their proposed structures are also presented in Fig. 9B. It should also be noted that the acetyl groups found on Cannabis extracted LHC1, as shown on Fig. 4, can be barely observed at 2.10 ppm, and seemed that they readily decomposed during the D2O heated dissolution. These findings are consistent with the proposed hemicellulose formation in monocots (Switchgrass) and dicots (Cannabis, Cardoon), presented in the literature [60].

In parallel, comparative FTIR spectra of both starting biomasses of the Switchgrass and the Cannabis and their corresponding extracted LHC1 s, also displayed in Fig. 9, zoomed in the relevant low wavenumber. Considering the compositional data of Table 4 via 1H NMR, it is interesting to note that, the 810 cm−1 peak of Switchgrass LHC1 resembles that of the biomass and seems absent in the other plant’s spectra. This provides evidence that the 810 cm−1 FTIR peak could be linked to the total arabinose content of the biomass, while the 780 and the 815 cm−1 peaks persistent in the other two plants link with the existence of the 4-O-methyl glucuronic acid in the biomass.

4 Conclusions

A complete chemical and analytical study was conducted on the biomasses of three seperate plants (i.e., Switchgrass, Cannabis, Cardoon). After reporting their consituents using standard wet chemical methods, a series of extraction protocols were performed to understand each constituent characteristics through thermogravimetry and mainly IR spectroscopy, allowing for qualitative verification of the results. Following defatting the samples and isolating fats, lipids and proteins, either hemicellulose or pectin were extracted and isolated. The remaining biomasses were thoroughly washed to remove unwanted byproducts and then measured again using FTIR to observe the structural changes from hydrolyses. This process allowed for a clearer understanding of the orgin of most of the IR peaks which were separated into spectral regions. Distinct peaks and regions regarding pectin (915 cm−1), cellulose (895 cm−1), hemicellulose (850−750 cm−1), lignin (1508 cm−1) and fats and lipids (720 and 728 cm−1) were extensively identified and were subjected to further mathematical analyses (peak fittings) to extract quantitative information. This quantitative methodology involved establishing calibration constants of each of the mentioned components by calculating the ratio of the normalized wet chemistry results to the fitted peak area or region. The results of this analysis yielded adequate results with a percent deviation of around 20%, proving the effectiveness of this methodology to estimate these components concentration in a biomass more quickly than traditional wet chemistry. This method could be helpful for biotechnological processes involving plant based feedstocks.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request.

References

Corma A, de la Torre O, Renz M, Villandier N (2011) Production of high-quality diesel from biomass waste products. Angew Chem Int Ed 50:2375–2378. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201007508

Penloglou G, Tissink A, Bakola V et al (2024) Efficient conversion of an underutilized low-lignin lignocellulosic biomass to cellulose nanocrystals and nanofibers via mild chemical-mechanical protocols. Bioresour Technol Rep 25:101799. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BITEB.2024.101799

Yu S, Sun J, Shi Y et al (2021) Nanocellulose from various biomass wastes: its preparation and potential usages towards the high value-added products. Environ Sci Ecotechnol 5:100077. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ESE.2020.100077

Sarafidou M, Vittou O, Psaki O et al (2024) Evaluation of alternative sugar beet pulp refining strategies for efficient pectin extraction and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) production. Biochem Eng J 208:109368. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BEJ.2024.109368

Zioga M, Tsouko E, Maina S et al (2022) Physicochemical and rheological characteristics of pectin extracted from renewable orange peel employing conventional and green technologies. Food Hydrocoll 132:107887. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODHYD.2022.107887

Rao J, Lv Z, Chen G, Peng F (2023) Hemicellulose: structure, chemical modification, and application. Prog Polym Sci 140:101675. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PROGPOLYMSCI.2023.101675

Roman-Benn A, Contador CA, Li MW et al (2023) Pectin: an overview of sources, extraction and applications in food products, biomedical, pharmaceutical and environmental issues. Food Chem Adv 2:100192. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOCHA.2023.100192

Meng A, Chen S, Zhou H et al (2015) Pyrolysis and simulation of typical components in wastes with macro-TGA. Fuel 157:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUEL.2015.04.056

Cozzani V, Lucchesi A, Stoppato G, Maschio G (1997) A new method to determine the composition of biomass by thermogravimetric analysis. Can J Chem Eng 75:127–133. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjce.5450750120

Díez D, Urueña A, Piñero R et al (2020) Determination of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin content in different types of biomasses by thermogravimetric analysis and pseudocomponent kinetic model (TGA-PKM method). Processes 8:1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8091048

Xu F, Yu J, Tesso T et al (2013) Qualitative and quantitative analysis of lignocellulosic biomass using infrared techniques: a mini-review. Appl Energy 104:801–809. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APENERGY.2012.12.019

McLellan TM, Aber JD, Martin ME et al (1991) Determination of nitrogen, lignin, and cellulose content of decomposing leaf material by near infrared reflectance spectroscopy. Can J For Res 21:1684–1688. https://doi.org/10.1139/x91-232

McLellan TM, Martin ME, Aber JD et al (1991) Comparison of wet chemistry and near infrared reflectance measurements of carbon-fraction chemistry and nitrogen concentration of forest foliage. Can J For Res 21:1689–1693. https://doi.org/10.1139/x91-233

Kenji Ono MH, Amari M (2003) Determination of lignin, holocellulose, and organic solvent extractives in fresh leaf, litterfall, and organic material on forest floor using near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy. J For Res 8:191–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10310-003-0026-2

McCann MC, Hammouri M, Wilson R et al (1992) Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy is a new way to look at plant cell walls. Plant Physiol 100:1940–1947. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.100.4.1940

Zhu J, Wang H, Guo F et al (2021) Cell wall polymer distribution in bamboo visualized with in situ imaging FTIR. Carbohydr Polym 274:118653. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CARBPOL.2021.118653

Sene CFB, McCann MC, Wilson RH, Grinter R (1994) Fourier-transform Raman and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (an investigation of five higher plant cell walls and their components). Plant Physiol 106:1623–1631. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.106.4.1623

He Z, Liu Y, Kim HJ et al (2022) Fourier transform infrared spectral features of plant biomass components during cotton organ development and their biological implications. J Cotton Res 5:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42397-022-00117-8

Canteri MHG, Renard CMGC, Le Bourvellec C, Bureau S (2019) ATR-FTIR spectroscopy to determine cell wall composition: application on a large diversity of fruits and vegetables. Carbohydr Polym 212:186–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CARBPOL.2019.02.021

Kora E, Tsaousis PC, Andrikopoulos KS et al (2023) Production efficiency and properties of poly(3hydroxybutyrate-co-3hydroxyvalerate) generated via a robust bacterial consortium dominated by Zoogloea sp. using acidified discarded fruit juices as carbon source. Int J Biol Macromol 226:1500–1514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.11.262

Li X, Sun C, Zhou B, He Y (2015) Determination of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin in moso bamboo by near infrared spectroscopy. Sci Rep 5:17210. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17210

Javier-Astete R, Jimenez-Davalos J, Zolla G (2021) Determination of hemicellulose, cellulose, holocellulose and lignin content using FTIR in Calycophyllum spruceanum (Benth.) K. Schum. and Guazuma crinita Lam. PLoS One 16:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256559

Lehto J, Louhelainen J, Kłosińska T et al (2018) Characterization of alkali-extracted wood by FTIR-ATR spectroscopy. Biomass Convers Biorefin 8:847–855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-018-0327-5

Stewart D, Wilson HM, Hendra PJ, Morrison IM (1995) Fourier-transform infrared and Raman spectroscopic study of biochemical and chemical treatments of oak wood (Quercus rubra) and barley (Hordeum vulgare) Straw. J Agric Food Chem 43:2219–2225. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf00056a047

Ribeiro da Luz B (2006) Attenuated total reflectance spectroscopy of plant leaves: a tool for ecological and botanical studies. New Phytol 172:305–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01823.x

Ben Atitallah I, Antonopoulou G, Ntaikou I et al (2022) A comparative study of various pretreatment approaches for bio-ethanol production from willow sawdust, using co-cultures and mono-cultures of different yeast strains. Molecules 27:1344. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27041344

Tsouko E, Maina S, Ladakis D et al (2020) Integrated biorefinery development for the extraction of value-added components and bacterial cellulose production from orange peel waste streams. Renew Energy 160:944–954. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RENENE.2020.05.108

Shin H-Y, Shim S-H, Ryu Y-J et al (2018) Lipid extraction from Tetraselmis sp. microalgae for biodiesel production using hexane-based solvent mixtures. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng 23:16–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12257-017-0392-9

Setti L, Samaei SP, Maggiore I et al (2020) Comparing the effectiveness of three different biorefinery processes at recovering bioactive products from hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Byproduct. Food Bioproc Tech 13:2156–2171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-020-02550-6

Melton LD, Smith BG (2001) Determination of the uronic acid content of plant cell walls using a colorimetric assay. Curr Protoc Food Anal Chem 00:E3.3.1-E3.3.4. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142913.fae0303s00

Sluiter A (2012) Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass: laboratory analytical procedure (LAP): Issue Date, April 2008, Revision Date: August 2012 (Version 08–03–2012). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. http://www.nrel.gov/biomass/analytical_procedures.html

Filippi K, Papapostolou H, Alexandri M et al (2022) Integrated biorefinery development using winery waste streams for the production of bacterial cellulose, succinic acid and value-added fractions. Bioresour Technol 343:125989. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIORTECH.2021.125989

Chong SL, Koutaniemi S, Virkki L et al (2013) Quantitation of 4-O-methylglucuronic acid from plant cell walls. Carbohydr Polym 91:626–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CARBPOL.2012.08.078

Bengtsson JD, Wallis JG, Browse J (2021) Lipid isolation from plants. In: Bartels D, Dörmann P (eds) Plant lipids: methods and protocols. Springer, US, New York, NY, pp 3–13

Lu Y, He Q, Fan G et al (2021) Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: a review. 10:779–804. https://doi.org/10.1515/gps-2021-0065

Larnaudie V, Ferrari MD, Lareo C (2022) Switchgrass as an alternative biomass for ethanol production in a biorefinery: perspectives on technology, economics and environmental sustainability. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 158:112115. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RSER.2022.112115

Santos-Sánchez G, Álvarez-López AI, Ponce-España E et al (2022) Hempseed (Cannabis sativa) protein hydrolysates: a valuable source of bioactive peptides with pleiotropic health-promoting effects. Trends Food Sci Technol 127:303–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TIFS.2022.06.005

Mandim F, Petropoulos SA, Giannoulis KD et al (2020) Chemical composition of Cynara cardunculus L. var. altilis bracts cultivated in central Greece: the impact of harvesting time. Agronomy 10:1976. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10121976

Zayed A, Serag A, Farag MA (2020) Cynara cardunculus L.: outgoing and potential trends of phytochemical, industrial, nutritive and medicinal merits. J Funct Foods 69:103937. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFF.2020.103937

Kačuráková M, Ebringerová A, Hirsch J, Hromádková Z (1994) Infrared study of arabinoxylans. J Sci Food Agric 66:423–427. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.2740660323

Martins JR, Llanos JHR, Abe MM et al (2024) New blend of renewable bioplastic based on starch and acetylated xylan with high resistance to oil and water vapor. Carbohydr Res 537:109068. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CARRES.2024.109068

Chatjigakis AK, Pappas C, Proxenia N et al (1998) FT-IR spectroscopic determination of the degree of esterification of cell wall pectins from stored peaches and correlation to textural changes. Carbohydr Polym 37:395–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0144-8617(98)00057-5

Fissore EN, Domingo CS, Pujol CA et al (2014) Upgrading of residues of bracts, stems and hearts of Cynara cardunculus L. var. scolymus to functional fractions enriched in soluble fiber. Food Funct 5:463–470. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3FO60561B

Sabater C, Corzo N, Olano A, Montilla A (2018) Enzymatic extraction of pectin from artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) by-products using Celluclast®1.5L. Carbohydr Polym 190:43–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CARBPOL.2018.02.055

Singhal S, Swami Hulle NR (2022) Citrus pectins: structural properties, extraction methods, modifications and applications in food systems – a review. Appl Food Res 2:100215. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AFRES.2022.100215

Laurens LML, Wolfrum EJ (2011) Feasibility of spectroscopic characterization of algal lipids: chemometric correlation of NIR and FTIR spectra with exogenous lipids in algal biomass. Bioenergy Res 4:22–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-010-9098-y

Taşar Ş, Özer A (2022) A comparative study of hemicellulose isolation with hot water, alkaline, and delignification methods from tea leaf brewing waste. Biomass Convers Biorefin 12:2501–2514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-020-00978-6

Oh SY, Il YD, Shin Y, Seo G (2005) FTIR analysis of cellulose treated with sodium hydroxide and carbon dioxide. Carbohydr Res 340:417–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CARRES.2004.11.027

Santos EE, Amaro RC, Bustamante CCC et al (2020) Extraction of pectin from agroindustrial residue with an ecofriendly solvent: use of FTIR and chemometrics to differentiate pectins according to degree of methyl esterification. Food Hydrocoll 107:105921. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODHYD.2020.105921

Rodrigues J, Faix O, Pereira H (1998) Determination of lignin content of Eucalyptus globulus wood using FTIR spectroscopy. 52:46–50. https://doi.org/10.1515/hfsg.1998.52.1.46

Sunkar B, Bhukya B (2022) An approach to correlate chemical pretreatment to digestibility through biomass characterization by SEM, FTIR and XRD. Front Energy Res 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2022.802522

Morais de Carvalho D, Abad AM, Evtuguin DV et al (2017) Isolation and characterization of acetylated glucuronoarabinoxylan from sugarcane bagasse and straw. Carbohydr Polym 156:223–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CARBPOL.2016.09.022

Bichara LC, Alvarez PE, Fiori Bimbi MV et al (2016) Structural and spectroscopic study of a pectin isolated from citrus peel by using FTIR and FT-Raman spectra and DFT calculations. Infrared Phys Technol 76:315–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INFRARED.2016.03.009

Abidi N, Cabrales L, Haigler CH (2014) Changes in the cell wall and cellulose content of developing cotton fibers investigated by FTIR spectroscopy. Carbohydr Polym 100:9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CARBPOL.2013.01.074

Barsberg S (2010) Prediction of vibrational spectra of polysaccharides—simulated IR spectrum of cellulose based on Density Functional Theory (DFT). J Phys Chem B 114:11703–11708. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp104213z

Barsberg S, Sanadi AR, Jørgensen H (2011) A new Density Functional Theory (DFT) based method for supporting the assignment of vibrational signatures of mannan and cellulose—analysis of palm kernel cake hydrolysis by ATR-FT-IR spectroscopy as a case study. Carbohydr Polym 85:457–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CARBPOL.2011.03.012

Hoffmann RA, Geijtenbeek T, Kamerling JP, Vliegenthart JFG (1992) 1H-N.m.r. study of enzymically generated wheat-endosperm arabinoxylan oligosaccharides: structures of hepta- to tetradeca-saccharides containing two or three branched xylose residues. Carbohydr Res 223:19–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/0008-6215(92)80003-J

Bowman MJ, Dien BS, Vermillion KE, Mertens JA (2015) Isolation and characterization of unhydrolyzed oligosaccharides from switchgrass (Panicum virgatum, L.) xylan after exhaustive enzymatic treatment with commercial enzyme preparations. Carbohydr Res 407:42–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CARRES.2015.01.018

Vignon MR, Gey C (1998) Isolation, 1H and 13C NMR studies of (4-O-methyl-d-glucurono)-d-xylans from luffa fruit fibres, jute bast fibres and mucilage of quince tree seeds. Carbohydr Res 307:107–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-6215(98)00002-0

Scheller HV, Ulvskov P (2010) Hemicelluloses. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61:263–289. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112315

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece. This research has been co‐financed by the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union and Greek national funds through the Operational Program Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation, under the call RESEARCH – CREATE – INNOVATE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and Methodology: George A. Voyiatzis, Apostolos A. Koutinas, Nicholaos G. Danalatos, Panagiotis C. Tsaousis. Experimentation—data analysis: Panagiotis C. Tsaousis, Mirva Sarafidou, Dimitrios Bartzialis.Writing the original draft: Panagiotis C. Tsaousis, Mirva Sarafidou, Kyrgiakos D. Giannoulis, Dimitrios Bartzialis. Reviewing—Editing: Amaia Soto Beobide, Georgios N. Mathioudakis, Konstantinos S. Andrikopoulos. Katiana Phillipi, Kyriakos D. Giannoulis. Supervision: George A. Voyiatzis, Apostolos A. Koutinas, Nicholaos G. Danalatos.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Additional consent was obtained from all the participating individuals included in this study.

Consent to participate

Consent was obtained from all the individuals participating in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsaousis, P.C., Sarafidou, M., Soto Beobide, A. et al. Quantification of plant biomass composition via a single FTIR absorption spectrum supported by reference component extraction/isolation protocols. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 15, 25273–25288 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-025-06858-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-025-06858-1