Abstract

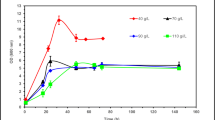

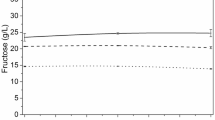

High starch sweetpotatoes (HSSPs) are renewable feedstocks with the potential to support industrially relevant chemical production. Here, three HSSP genotypes (NC-413, NCPUR06-020, and NCDM02-180) and a table-stock variety (Covington) were tested for butanol production by Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 in two process configurations, separate hydrolysis and fermentation (SHF) and simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF). Results indicated that sweetpotato genotype, preparation (fresh vs flour), and system configuration significantly affected acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE) fermentation efficiency. Particularly, conversion using the Covington variety showed the highest product yields and robust results with both preparations (0.137 and 0.094 g butanol/g initial starch for fresh and flour preparations, respectively) without requiring pre-processing for phenolic removal with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP). On the other hand, cultures with purple varieties NC-413 and NCPUR06-020, with the exception of NCPUR06-020 fresh preparations, required anthocyanin removal to achieve 0.103 g butanol/g initial starch, which represented more than a 1.6-fold increase in butanol concentration compared to purple sweetpotato hydrolysates without PVP phenolic pretreatment. Conversions with the white genotype (NCDM02-180) showed the lowest performance and largest variability under a SHF configuration (0.012 to 0.034 g butanol/g initial starch for fresh and flour, respectively), while butanol yields under SSF conditions (0.069 g butanol/g initial starch) were similar to the other genotypes examined. This study establishes the feasibility of using regionally relevant sweetpotato feedstocks (e.g., non-food-intended varieties as well as table-stock residues or culls) as a source of crude sugars for butanol fermentation and some of the key processing conditions that influence C. beijerinckii culture performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

Veza I, Muhamad Said MF, Latiff ZA (2021) Recent advances in butanol production by acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE) fermentation. Biomass Bioenerg 144:105919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2020.105919

Cao Y, Tian H, Yao K, Yuan Y (2011) Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of sweet potato powder for the production of ethanol under conditions of very high gravity. Front Chem Sci Eng 5:318–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11705-010-1026-3

Diaz JT, Chinn MS, Truong V-D (2014) Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of industrial sweetpotatoes for ethanol production and anthocyanins extraction. Ind Crops Prod 62:53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.07.032

Duvernay WH, Chinn MS, Yencho GC (2013) Hydrolysis and fermentation of sweetpotatoes for production of fermentable sugars and ethanol. Ind Crops Prod 42:527–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.06.028

Srichuwong S, Fujiwara M, Wang X et al (2009) Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF) of very high gravity (VHG) potato mash for the production of ethanol. Biomass Bioenerg 33:890–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2009.01.012

Santa-Maria M, Pecota KV, Yencho CG et al (2009) Rapid shoot regeneration in industrial “high starch” sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L.) genotypes. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 97:109–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11240-009-9504-3

Truong VD, Avula RY, Pecota K, Yencho CG (2018) Sweetpotato production, processing and nutritional quality. In: Siddiq M, Uebersax MAE (eds) Handbook of vegetables and vegetable processing, 2nd edn. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Co, Ames, pp 811–838

USDA (2022) Vegetables 2021 Summary. https://usda.library.cornell.edu/concern/publications/02870v86p?locale=en. Accessed 16 Mar 2022

Dewan A, Li Z, Han B, Karim MN (2013) Saccharification and fermentation of waste sweet potato for bioethanol production. J Food Process Eng 36:739–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpe.12042

Edmunds B, Boyette M, Clark C et al (2008) Postharvest handling of sweetpotatoes. North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service. https://plantpathology.ces.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/sweetpotatoes_postharvest-1.pdf?fwd=no. Accessed 27 Jul 2022

Ziska LH, Runion GB, Tomecek M et al (2009) An evaluation of cassava, sweet potato and field corn as potential carbohydrate sources for bioethanol production in Alabama and Maryland. Biomass Bioenerg 33:1503–1508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2009.07.014

Pugazhendhi A, Mathimani T, Varjani S et al (2019) Biobutanol as a promising liquid fuel for the future - recent updates and perspectives. Fuel 253:637–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.04.139

Wang Y, Janssen H, Blaschek HP (2014) Fermentative biobutanol production: an old topic with remarkable recent advances. In: Bisaria VS, Kondo A (eds) Bioprocessing of renewable resources to commodity bioproducts. John Wiley & Sons Inc, Hoboken, pp 227–260

Shin YA, Choi S, Han M (2021) Simultaneous fermentation of mixed sugar by a newly isolated Clostridium beijerinckii GSC1. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng 26:137–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12257-020-0183-6

Abo BO, Gao M, Wang Y et al (2019) Production of butanol from biomass: recent advances and future prospects. Environ Sci Pollut Res 26:20164–20182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05437-y

Sandoval-Espinola WJ (2016) A story of gases and electrons: unveiling Clostridium beijerinckii aerotolerance and its assimilation of greenhouse gas to n-butanol. Dissertation, North Carolina State University

Lee J, Blaschek HP (2001) Glucose uptake in Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 and the solvent-hyperproducing mutant BA101. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:5025–5031. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.67.11.5025

Sandoval-Espinola WJ (2013) Butanol from sweet sorghum juice by Clostridium beijerinckii SA-1 / ATCC 35702, a butanol hyper-producing strain. Theses, North Carolina State University

Sandoval-Espinola WJ, Chinn MS, Thon MR, Bruno-Bárcena JM (2017) Evidence of mixotrophic carbon-capture by n-butanol-producer Clostridium beijerinckii. Sci Rep 7:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12962-8

Badr HR, Hamdy MK (1992) Optimization of acetone-butanol production using response surface methodology. Biomass Bioenerg 3:49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/0961-9534(92)90019-M

Badr HR, Toledo R, Hamdy MK (2001) Continuous acetone – ethanol – butanol fermentation by immobilized cells of Clostridium acetobutylicum. Biomass Bioenerg 20:119–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0961-9534(00)00068-4

Yen HW, Li RJ, Ma TW (2011) The development process for a continuous acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE) fermentation by immobilized Clostridium acetobutylicum. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 42:902–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2011.05.006

Ezeji T, Qureshi N, Blaschek HP (2007) Butanol production from agricultural residues: impact of degradation products on Clostridium beijerinckii growth and butanol fermentation. Biotechnol Bioeng 97:1460–1469. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.21373

Lee S, Lee JH, Mitchell RJ (2015) Analysis of Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052’s transcriptional response to ferulic acid and its application to enhance the strain tolerance. Biotechnol Biofuels 8:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-015-0252-9

He J, Giusti MM (2010) Anthocyanins: natural colorants with health-promoting properties. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol (new 2010) 1:163–187. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.food.080708.100754

Brudzyńska P, Sionkowska A, Grisel M (2021) Plant-derived colorants for food, cosmetic and textile industries: a review. Materials (Basel) 14:1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14133484

Yencho GC, Pecota KV, Driscoll JE (2014) Industrial sweetpotato plant named NCPURO6-O2O. United States Patent 2014(0366234):P1

Zuleta-Correa A, Chinn MS, Alfaro-Córdoba M et al (2020) Use of unconventional mixed acetone-butanol-ethanol solvents for anthocyanin extraction from purple-fleshed sweetpotatoes. Food Chem 314:125959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125959

Ridley SC, Lim M, Heenan S, Bremer P (2005) Evaluation of sweet potato cultivars and heating methods for control of maltose production, viscosity and sensory quality. J Food Qual 28:191–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-4557.2005.00013.x

Diaz JT, Veal MW, Chinn MS (2014) Development of NIRS models to predict composition of enzymatically processed sweetpotato. Ind Crops Prod 59:119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.05.012

Sandoval-Espinola WJ, Chinn M, Bruno-Barcena JM (2015) Inoculum optimization of Clostridium beijerinckii for reproducible growth. FEMS Microbiol Lett 362:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnv164

Lee J, Durst RW, Wrolstad RE (2005) Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the pH differential method: Collaborative study. J AOAC Int 88:1269–1278. https://doi.org/10.5555/jaoi.2005.88.5.1269

Fazekas E, Szabó K, Kandra L, Gyémánt G (2013) Biochimica et Biophysica Acta Unexpected mode of action of sweet potato β -amylase on maltooligomer substrates. BBA - Proteins Proteomics 1834:1976–1981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.06.017

Lareo C, Ferrari MD, Guigou M et al (2013) Evaluation of sweet potato for fuel bioethanol production: hydrolysis and fermentation. Springerplus 2:493. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-493

Arantes V, Saddler JN (2011) Cellulose accessibility limits the effectiveness of minimum cellulase loading on the efficient hydrolysis of pretreated lignocellulosic substrates. Biotechnol Biofuels 4:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1754-6834-4-3

Jönsson LJ, Alriksson B, Nilvebrant N (2013) New developments in microwave histoprocessing. Biotechnol Biofuels 6:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1754-6834-6-16

Woo KS, Kim HY, Hwang IG et al (2015) Characteristics of the thermal degradation of glucose and maltose solutions. Prev Nutr Food Sci 20:102–109. https://doi.org/10.3746/pnf.2015.20.2.102

Oba K, Murakami S, Uritani I (1977) Partial purification and characterization of L-lactate dehydrogenase isozymes from sweet potato roots. J Biochem 81:1193–1201

Bridgers EN, Chinn MS, Truong VD (2010) Extraction of anthocyanins from industrial purple-fleshed sweetpotatoes and enzymatic hydrolysis of residues for fermentable sugars Ind Crops Prod 32:613–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2010.07.020

Patras A, Brunton NP, O’Donnell C, Tiwari BK (2010) Effect of thermal processing on anthocyanin stability in foods; mechanisms and kinetics of degradation. Trends Food Sci Technol 21:3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2009.07.004

Diez-gonzalez F, Russell JB, Hunter JB (1997) NAD-independent lactate and butyryl-CoA dehydrogenases of Clostridium acetobutylicum P262. Curr Microbiol 34:162–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002849900162

Zhu Y, Yang S (2004) Effect of pH on metabolic pathway shift in fermentation of xylose by Clostridium tyrobutyricum. J Biotechnol 110:143–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2004.02.006

Wang S, Zhang Y, Dong H et al (2011) Formic acid triggers the “acid crash” of acetone-butanol-ethanol fermentation by Clostridium acetobutylicum. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:1674–1680. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01835-10

Ljungdahl LG (1986) The autotrophic pathway of acetate synthesis in acetogenic bacteria. Ann Rev Microbiol 40:415–50. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.mi.40.100186.002215

Ragsdale SW (2008) Enzymology of the Wood – Ljungdahl pathway of acetogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1125:129–136. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1419.015

Thauer RK, Kirchniawy FH, Jungermann KA (1972) Properties and function of the pyruvate-formate-lyase reaction in Clostridiae. Eur J Biochem 27:282–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1972.tb01837.x

Cho DH, Shin SJ, Kim YH (2012) Effects of acetic and formic acid on ABE production by Clostridium acetobutylicum and Clostridium beijerinckii. Biotechnol Bioproc E 17:270–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12257-011-0498-4

Neely GL (1946) Japanese Fuels and Lubricants, Article 3: naval research on alcohol Fuel [X-38(N)-3]. United States

He CR, Huang CL, Lai YC, Li SY (2017) The utilization of sweet potato vines as carbon sources for fermenting bio-butanol. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 79:7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2017.02.022

Luo W, Zhao Z, Pan H et al (2018) Feasibility of butanol production from wheat starch wastewater by Clostridium acetobutylicum. Energy 154:240–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.04.125

Li H, Ma Xx, Zhang Qh et al (2016) Enhanced butanol production by solvent tolerance Clostridium acetobutylicum SE25 from cassava flour in a fibrous bed bioreactor. Bioresour Technol 221:412–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.08.120

Li H, Ofosu FK, Li K et al (2014) Acetone, butanol, and ethanol production from gelatinized cassava flour by a new isolates with high butanol tolerance. Bioresour Technol 172:276–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.09.058

Liu J, Lin Q, Chai X et al (2018) Enhanced phenolic compounds tolerance response of Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 by inactivation of Cbei_3304. Microb Cell Fact 17:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-018-0884-0

Yoshimoto M, Okuno S, Yamaguchi M, Yamakawa O (2001) Antimutagenicity of deacylated anthocyanins in purple-fleshed sweetpotato. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 65:1652–1655. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.65.1652

Ferreira P, Lima C, Freitas AA et al (2005) Charge-transfer complexation as a general phenomenon in the copigmentation of anthocyanins. J Phys Chem 109:7329–7338. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp052106s

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación de Colombia (MinCiencias) and Fulbright-Colombia (grant 568-2012) for providing funding for the doctoral student Ana Zuleta-Correa. On behalf of Dr. Zuleta-Correa we would like to thank INVEMAR’s Marine Bioprospecting Line colleagues for their support during the publication and correction process (Contribution No. 1338). The authors also wish to thank Dr. Craig Yencho and Mr. Ken Pecota (Sweetpotato Breeding Program, NCSU) for supplying fresh sweetpotatoes and Dr. Matthew B. Whitfield for his assistance in HPLC analysis.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grant 568–2012 of Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación de Colombia (MinCiencias) and Fulbright-Colombia and the North Carolina Agricultural Research Service as part of Mari Chinn’s experiment station Hatch project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ana Zuleta-Correa: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing, visualization.

Mari S. Chinn: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing-review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

José M. Bruno-Bárcena: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zuleta-Correa, A., Chinn, M.S. & Bruno-Bárcena, J.M. Application of raw industrial sweetpotato hydrolysates for butanol production by Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 14, 9473–9490 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-022-03101-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-022-03101-z