Abstract

In spite of the widely accepted need for language-responsive subject-matter teaching, few teachers are prepared for this challenge due to the lack of empirically founded subject-specific professional development (PD) programs for language-responsive classrooms. The design research study presented in this article pursues the dual aim of (a) promoting teachers’ expertise in language-responsive mathematics teaching using PD courses and (b) investigating teachers’ developing expertise in qualitative case studies. Both aims are pursued based on a conceptual framework for teacher expertise in language-responsive mathematics teaching, starting from typical situational demands that teachers face in language-responsive mathematics teaching and the orientations, categories, and pedagogical tools they need to cope with these situational demands, especially the demand to identify mathematically relevant language demands. For language-responsive teaching, the interplay of categories for mathematical goals and language goals turns out to be of high relevance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

For nearly 40 years, research has pointed to challenges in linguistically diverse classrooms (Austin and Howson 1979; Ellerton and Clarkson 1996). Until now, language proficiency in school academic language has been a crucial factor with a high impact on mathematics achievement (Secada 1992; Haag et al. 2013; Marshman et al. 2015). The language gap exists not only for multilingual students but also for monolingual students from socially underprivileged families, and mainly refers to conceptual understanding rather than procedures (Prediger et al. 2018; Meaney et al. 2012).

Due to the relevance of language proficiency for achieving mathematical conceptual understanding, subject-matter teachers are requested to arrange their classrooms in language-responsive ways. This requires teaching approaches that not only reduce language demands but also support language learners to develop language proficiency that is relevant to the subject matter being learned (Thürmann et al. 2010; Echevarria, Vogt and Short 2010). Hence, the improvement of teachers’ expertise in language-responsive teaching is an important goal in pre-service and in-service teacher education throughout all subjects (Lucas and Villegas 2013), especially in mathematics (Adler 1995).

However, subject-matter teachers still face a profound lack of opportunity to learn and develop the required expertise (Adler 1995; Essien et al. 2016). Although some language education programs address not only language teachers but also mathematics teachers (Short 2017; Lucas and Villegas 2013), the designs of most professional development (PD) programs have not yet been specific enough to meet the language demands of a specific subject (Hajer 2006). In particular, this subject specificity comprises the necessary knowledge and practices for integrating mathematics and language learning in a mathematics-specific way (Hajer 2006; Essien et al. 2016).

The intent of the project presented in this article is to contribute to filling this gap by developing and investigating PD opportunities for mathematics teachers with a focus on integrating mathematics and language learning. The project was conducted using the methodological framework of content-specific design research for teachers (Prediger et al. 2016, following Cobb et al. 2003) and PD content covering language-responsive mathematics teaching. The project pursues a two-part question on PD design and PD research: what are teachers’ knowledge bases for coping with the demands of language-responsive teaching in the beginning of their PD courses, and what PD activities can enrich these knowledge bases?

The “Theoretical framework: conceptualizing teacher expertise for language-responsive mathematics teaching” section presents the conceptual framework for structuring content-specific teacher expertise and for designing PD courses aiming at disentangling its components. The methodological framework of design research is outlined in the “Methodology and methods of design research for teachers” section, together with the concrete methods of data gathering and data analysis for the case studies analysed in this article. The “Results: empirical insights into teachers’ learning pathways towards language-responsive mathematics teaching” section presents one case from the first design experiment cycle, the consequences that were iteratively drawn for the PD design for the example of one PD activity, and further case studies of teachers working in this activity . The “Discussion and conclusion” section summarises the main results and embeds them in the literature. The study shows that teachers require categories for connecting procedural and conceptual knowledge with different discourse practices and different vocabularies to be able to integrate content and language learning. The study also shows how these can be developed.

Theoretical framework: conceptualising teacher expertise for language-responsive mathematics teaching

In this section, a theoretical framework is presented detailing exactly what teachers need to learn in PD courses for language-responsive mathematics teaching. The section provides the general framework for conceptualising teacher expertise for specific PD content, and the section applies this framework in order to specify the necessary teacher expertise for language-responsive mathematics teaching.

Conceptual framework for content-specific teacher expertise

According to Shulman’s (1986) classical distinction, teacher knowledge comprises content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge. In the case of language-responsive teaching, content knowledge refers to mathematics and language, and pedagogical content knowledge to the role of language for teaching and learning of mathematics (Bunch 2013).

As the research review by Depaepe et al. (2013) has outlined, pedagogical content knowledge has most often been conceptualised in cognitive perspectives of knowledge and orientations (e.g. Kunter et al. 2013). Recently, increasing attention has been given to situated perspectives on teachers’ classroom practices, in addition to knowledge and orientations. Rather than emphasising the differences between cognitive and situated perspectives, Depaepe et al. (2013) and Blömeke et al. (2015) suggest considering knowledge and practices as complimentary in a continuum from disposition to performance.

One conceptualisation that originally addressed both dispositions and performances was Weinert’s (2001) influential definition of competence as the personal capacity to cope with specific, work-related situational demands:

The theoretical construct of action competence comprehensively combines those intellectual abilities, content-specific knowledge, cognitive skills, domain-specific strategies, routines and subroutines, motivational tendencies, volitional control systems, personal value orientations, and social behaviors into a complex system. Together, this system specifies the prerequisites required to fulfill the demands of a particular professional position. (Weinert 2001, p. 51)

Whereas Weinert (2001) originally addressed both dispositions and performances, most empirical research in psychological assessment referring to his work has mainly focused on knowledge and attitudes and not practices (Blömeke et al. 2015). In line with Weinert’s original intentions is Bromme’s (1992, 2001) construct of teacher expertise, which relates teachers’ practices for coping with situational demands to the categories and orientations they refer to. In this construct, Bromme anticipated Blömeke et al.’s (2015) and Depaepe et al.’s (2013) call for combining cognitive and situated perspectives and provided a theoretical background for capturing their relation to each other.

Based on these early ideas of Bromme (1992), the research presented here relies on a framework for conceptualising content-specific teacher expertise (Prediger 2019) by considering teachers’ situated practices to cope with situational demands in real or simulated classroom situations and their interplay with the underlying orientations, categories, and concrete pedagogical tools. More precisely, the five constructs of the framework for content-specific teacher expertise are defined as follows:

-

Jobs are defined as the typical, often complex situational demands of subject-matter teaching that are most relevant to the PD content in view.

-

Practices are defined as the recurrent patterns of teachers’ utterances and actions for coping with these jobs. Teacher practices can be characterised by the underlying categories, pedagogical tools, and orientations upon which the teachers’ actions implicitly or explicitly draw.

-

Pedagogical tools are the concrete, visible tools applied to coping with the job (e.g. tasks, facilitation moves, activity structures, and didactical artefacts).

-

Orientations refer to content-related and more general beliefs that implicitly or explicitly guide the teachers’ perceptions and prioritisations of jobs (e.g. beliefs about the content or students’ learning processes; see Schoenfeld 2010, p. 29).

-

Categories are conceptual (i.e. non-propositional) knowledge elements that filter and focus the categorical perception and the thinking of the teacher that usually stem from knowledge on the classroom content, pedagogical content knowledge (e.g. knowledge about learning processes) or from generic pedagogical knowledge. Although propositional knowledge might also be relevant, we follow Bromme in focusing knowledge to non-propositional conceptual knowledge, i.e. teachers’ categories for thinking and noticing.

This general conceptual framework raises the methodological question of how to determine which categories and orientations are required for teachers. Bromme (1992) suggests a powerful “heuristic to search for the ‘natural’ categories in expert knowledge” (p. 88) by analysing the situational demands with respect to the relevant practices and their underlying categories and orientations. This methodological approach resonates with the job analysis that Ma (1999) and Bass and Ball (2004) presented for determining the necessary mathematical knowledge for teaching. Whereas these researchers focus on the mathematical knowledge to be specified by a job analysis, this paper focuses on the pedagogical content knowledge necessary for PD content language-responsive mathematics teaching. A similar framework has been developed by Grossman et al. (1999) for English language teachers. Based on activity theory, they also placed teachers’ practices (activities) in the centre of their conceptualisation and tried to identify the necessary conceptual tools and pedagogical tools for enacting these practices. Within this framework, they conceptualised teacher professionalisation as appropriation of practices, and conceptual and pedagogical tools. The framework of this article borrows the construct of pedagogical tools from their framework, and comprises, for example, task formats or activity structures that a teacher applies.

Whereas Bromme (1992) and Grossman et al. (1999) conducted epistemological analyses of practices in order to specify the necessary conceptual and pedagogical tools of a generic, ideal teacher, Vergnaud’s (1998) conceptualisation also offers a theoretical foundation for empirically investigating teachers’ practices. In his brief sketch on teachers, Vergnaud (1998) extends his learning theory of conceptual fields to teacher expertise. Vergnaud (1996) describes it as “a fruitful and comprehensive framework for studying complex cognitive competences and activities and their development” (p. 219). He assumes that for each situation, every individual and every community develops certain schemes of action to cope with these situations. These schemes are, implicitly or explicitly, guided by so-called situational invariants, including theorems- and concepts-in-action, the latter are relevant for the study of this article. Vergnaud defines concepts-in-action as “categories ... that enable the subject to cut the world into distinct … aspects and pick up the most adequate selection of information” (p. 219). Here, for example, categories distinguishing the word level (i.e. referring to vocabulary aspects) and discourse level of language (i.e. referring to discourse practices such as arguing and explaining). Thus, Vergnaud’s concepts-in-action can methodologically underpin Bromme’s (1992) construct of categorical perception and Grossman et al.’s (1999) conceptual tools.

This article applies Vergnaud’s methodology to refine Bass and Ball’s (2004) and Bromme’s (1992) job analysis on the microlevel of teachers’ individual or shared practices. According to Vergnaud’s methodology, individual and recurring concepts-in-action can be reconstructed as the internal mental backgrounds of teachers’ actions or utterances even if they are still implicit for the teacher. This methodology has proven to reveal a powerful methodological approach for capturing students’ learning pathways (e.g. in Prediger and Zindel 2017) and is now shifted to the level of teacher. Vergnaud (1998) himself has suggested applying the framework to teachers in order to overcome the conceptual divide between theory and practice.

To sum up, this paper conceptualises teachers’ professional content-specific expertise as the personal capacity to cope with situational demands called jobs. The content in view is language-responsive mathematics teaching. The pathway from the current to the intended expertise can be unpacked by specifying the necessary orientations for teachers’ (current and intended) practices to cope with the jobs and by empirically reconstructing the underlying categories that should or do guide their practices.

Disentangling teacher expertise for language-responsive mathematics teaching

A large body of design research and observations studies on the classroom level have provided empirical findings on effective language-responsive mathematics teaching and its theoretical backgrounds (overview in Moschkovich 2013; Planas and Schütte 2018). They show that language-responsiveness cannot be restricted to the communicative function of language, but must take into account its epistemic function as a tool for thinking and knowledge acquisition (Pimm 1987; Prediger and Zindel 2017). When differences between the students’ everyday-language resources and the academic-language demands in classrooms are identified, these encompass not only the word level of unknown vocabulary but also differences on the sentence level of more complex syntactical structures and on the level of more complex and abstract discourse practices such as explaining or arguing (Meaney et al. 2012; Snow and Uccelli 2009). From a functional linguistic perspective, the word level (with its lexical features) and sentence level (with its syntactical features) are subordinated as the language means required for participating in discourse practices (Schleppegrell 2007; Snow and Uccelli 2009). Among all discourse practices, describing general patterns and explaining meanings have turned out to be most relevant for language learners: language learners can develop procedural knowledge without rich discourse practices, but little conceptual knowledge is developed unless they succeed in participating in the discourse practice of explaining meanings (Adler 1995; Moschkovich 2013; Prediger 2019). However, language-responsive classrooms have often been criticised for an isolated focus on vocabulary work as an end in itself (Moschkovich 2013; Schleppegrell 2007).

Although these findings are well known, they do not yet clarify what teachers need to learn for language-responsive mathematics teaching. As Hajer and Norén (2017) have emphasised, disentangling the possible PD contents for language-sensitive mathematics teaching is a complex endeavour that requires taking into account research results on both learning and teaching.

According to the framework developed in the “Conceptual framework for content-specific teacher expertise” section, this article conceptualises teacher expertise by specifying the situational demands (jobs) as well as selected orientations, categories and tools required for mathematics teachers to meet these demands. The first step of specification of jobs, orientations and categories is informed by a systematic literature search (starting from the review in Bunch 2013 and approaches in Hajer and Norén 2017 and Lucas and Villegas 2013, as well as previous empirical studies in Prediger 2019 and Prediger et al. 2018a).

Jobs in language-responsive mathematics teaching

From the cited literature and studies, five jobs for teachers in language-responsive mainstream mathematics classrooms can be inferred (throughout the article, the jobs will be marked in capital letters for easier recognition).

-

NOTICING language resources and further learning needs in students’ utterances and written products (e.g. with pedagogical tools for formative assessment)

-

DEMANDING language in cognitively and discursively rich learning situations (e.g. by the pedagogical tools of writing tasks asking for explaining or of activity structures initiating student talk)

-

SUPPORTING language so that students can fulfil demands slightly above their current proficiency level (e.g. by the pedagogical tools of word banks or micro-scaffolding moves)

-

DEVELOPING language of students from a longer-term perspective (e.g. by connecting everyday language to school academic language and technical language and constantly working towards further development)

-

IDENTIFYING mathematically relevant language demands so that the noticing and supporting can focus on crucial rather than peripheral demands.

DEMANDING and SUPPORTING language are important jobs for all language learning (e.g. Smit et al. 2016). Gibbons (2002) has shown that high demands and high support result in the highest language-learning effects. For the demands and the support to be adaptive for each student, NOTICING is relevant to all teaching (Empson and Jacobs 2008). The longer-term perspective on successively DEVELOPING language builds upon the first three jobs, but additionally requires longer term planning beyond the single lesson to provide language learning trajectories over a teaching unit or a year (Echevarria et al. 2010; Gibbons 2002; Lucas and Villegas 2013).

Although the fifth job of IDENTIFYING language demands is often neglected by subject-independent conceptualisations of teacher expertise, previous research has shown its high relevance for achieving an integration of language and content learning (Hajer 2006; Prediger 2019), as it underlies the four other jobs: as long as teachers NOTICE, DEMAND, and SUPPORT only language features that are not central to mathematics learning (as often observed in classroom studies, e.g. Moschkovich 2013, for a summary), the language learning cannot sufficiently support the mathematics learning.

Pedagogical tools for coping with jobs in language-responsive mathematics teaching

Teachers’ practices for mastering the jobs can be mediated by pedagogical tools such as formative assessment tools for NOTICING language, discursively activating tasks and activity structures such as jigsaw structure or writing tasks for DEMANDING language, formats for scaffolding such as phrase lists or cloze formats for SUPPORTING students’ language production and longer-term word banks for DEVELOPING language during a teaching unit (Echeverria et al. 2010; Gibbons 2002).

Orientations guiding the coping with jobs in language-responsive mathematics teaching

One general orientation has often been emphasised as an important prerequisite before teachers engage in language-responsive teaching practices and apply pedagogical tools, namely accepting and valuing language diversity (e.g. Byrnes et al. 1997; Essien et al. 2016). Although Byrnes et al. (1997) prioritise this orientation as “positive language attitudes” and investigate the connection to previous experiences within language diverse classrooms, this orientation alone is not sufficient to cope with the jobs listed above as it gives no sufficiently clear directions for teachers’ practices. Three further orientations can guide the teachers’ practices for coping with the five situational demands more directly:

-

Assuming responsibility for students’ language learning: Mathematics teachers need to acknowledge the language diversity of their students and assume their responsibility for language as a learning goal in their mathematics classrooms (Adler 1995; Lucas and Villegas 2013; Lyon 2013; McLeman et al. 2012).

-

Striving for pushing instead of reducing language: Whereas some teachers tend to react to diverse language proficiencies by constantly reducing the language demands (Lyon 2013), researchers have emphasised the relevance of the general attitude that language production should be pushed in order to enable students’ language development with language demands in the zone of their proximal development (Austin and Howson 1979; Gibbons 2002; Moschkovich 2013). Teachers holding this orientation have been shown to take more effective actions (Lyon 2013).

-

Integrative instead of additive: Language learning should not be considered as an additum in mathematics classrooms. Instead, teachers should hold the general orientation that content and language learning can be integrated in order to reach mathematical content goals (Moschkovich 2002; Schleppegrell 2007; Smit and van Eerde 2011), starting from identifying the language demands in concrete mathematical learning situations. Teacher practices oriented towards this attitude have been shown to be effective (Short 2017; Zahner et al. 2012).

As the first case study in the empirical section of this article will again confirm, the first two orientations underlie the four jobs that focus on how language learning can be fostered, the third orientation can only be realised by combining these four jobs with the fifth job, which focuses the subject-related what question: asking what students should learn in language-responsive mathematics classrooms.

Categories for coping with jobs in language-responsive mathematics teaching

Whereas various pedagogical tools, and a short list of general orientations, have been identified to be relevant for language-responsive teaching along the jobs, the specific knowledge or categories that teachers need to activate for meeting these demands and realising these orientations has not yet been selected from the too-huge body of potentially relevant knowledge and approaches (Lucas and Villegas 2013; Planas and Schütte 2018). Zahner et al. (2012) give some indications for selection as they investigate what knowledge expert teachers activate when successfully fostering their language learners’ mathematics learning. The difference between conceptual and procedural mathematical knowledge turns out to be a crucial category, as the language learners’ conceptual knowledge should be the main mathematical goal. In order to reach this goal, expert teachers focus on demanding rich discourse practices rather than on vocabulary at the word level. Hence, from the study of Zahner et al. (2012), the categories ||conceptual versus procedural knowledge|| and ||discourse practices|| can be identified as relevant (in this article, categories are marked with “||...||” for easier recognition). Whereas the investigated expert teachers seemed to combine a rich network of different tools and categories, more research is required to identify the most important categories for teachers, beginning with language-responsive teaching for their first steps of teachers’ learning trajectories.

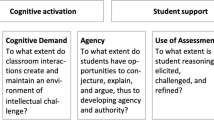

To sum up, Fig. 1 lists the jobs, pedagogical tools, orientations and some first categories for language-responsive mathematics teaching. Whereas the pedagogical tools mainly belong to a single job, the categories and orientations are linked to several jobs, so the figure should not be read as a matrix: The job of IDENTIFYING is based on all four other jobs. The figure also illustrates the research gap in the relevant categories. This article intends to contribute to close this gap and to show how the categories are connected to each other. For this purpose, the article focuses on the jobs of SUPPORTING language and IDENTIFYING language demands after DEMANDING rich discourse practices.

From the classroom research on language-responsive mathematics classrooms, these sketched jobs, tools, categories and orientations can be inferred as crucial for promoting language learners’ learning in a content- and language-integrated learning environment. The presented conceptualisation of teacher expertise for language-responsive mathematics teaching has been developed with respect to the jobs and orientations while observing teachers’ professionalisation processes; thus, it includes typical difficulties on this pathway (Prediger 2019). In the empirical part of this paper, the interplay of jobs and orientations with the categories will be examined more thoroughly while tracing teachers’ learning pathways through this specified PD content in order to empirically support the selection of relevant categories.

Design principles for the PD design

Starting from the presented conceptualisation of teacher expertise as the ability to activate a complex interplay of content-related orientations, pedagogical tools, and underlying categories for fulfilling typical jobs, the design of the PD program is structured around the joint exploration of different jobs. Following approaches of situated learning (Brown et al. 1989; Bromme 1992), the main activities in the PD refer to these jobs and thereby simulate typical classroom situations. In continuous PD (CPD) of 4–6 sequential PD sessions during 1–2 years, teachers experiment with the jobs in their classrooms between the PD sessions (e.g. by exploring writing tasks or new language-responsive activity structures or experimenting with written scaffolds). They then bring classroom documents back to the PD to reflect on their experiences with respect to their potential to enhance conceptual understanding. Reflection phases are crucial for connecting some (partly new) categories and pedagogical tools with the jobs, starting from the teachers’ resources and then extending them by shifts of attention (Vergnaud 1998). This design is in line with design principles that were shown to be effective for PD, especially case relatedness, participant orientation starting from teachers’ resources, inquiry cycles, and promoting collective reflection (Timperley et al. 2007).

In order for well-prepared facilitators to strengthen participant orientation, however, more systematic knowledge on teachers’ typical starting points, learning pathways and obstacles is necessary (Goldsmith et al. 2014). On the level of categories, this knowledge is to be generated by empirically studying teachers’ pathways on two selected jobs: SUPPORTING language and IDENTIFYING language demands.

Refined research questions

The theoretical framework provides the base to articulate the research questions in a more elaborate way, here with a focus on two jobs and the relevant categories:

-

Which categories do teachers activate in the beginning of a PD course for fulfilling the jobs of SUPPORTING language and IDENTIFYING language demands?

-

How can teachers’ repertoires of activated categories be enriched, connected and made explicit by PD activities?

Methodology and methods of design research for teachers

Methodological framework: design research for teachers

The dual aim of promoting and investigating teachers’ pathways towards expertise in language-responsive mathematics teaching calls for a design research methodology. Design research is a widely established research methodology for enhancing and investigating student learning. The methodology is especially strong when two aims are to be combined: (1) designing learning arrangements for classrooms and (2) investigating the initiated learning processes and contributing to local instruction theories (Cobb et al. 2003; Plomp and Nieveen 2013). Here, design research is extended from students’ learning to teachers’ PD. Content-specific design research for teachers’ aims at robust designs for PD courses, including empirical insights into possible challenges of the content to be learned and typical professionalisation processes (Prediger et al. 2016). This methodology resonates with the call by Goldsmith et al. (2014) for an empirical focus on teachers’ professionalisation processes rather than only on quantitatively measurable effects. As the research gap is even bigger for content-specific professionalisation processes, it is a major aim of the approach presented here to provide fine-grained insights into teachers’ processes of professionalisation in a specific PD content area.

Figure 2 shows the four working areas that are iteratively connected in the design and research process. The four working areas comprise (a) specifying and structuring PD goals and contents in hypothetical intended professionalisation trajectories (in this article: disentangling teacher expertise for language-responsive mathematics teaching; see the “Disentangling teacher expertise” section and the research questions), (b) developing the specific PD design (see the “Design principles” section and the design consequences for a concrete activity in the empirical section “case of Martin Schreiber”), (c) conducting and analysing design experiments in PD settings, and (d) developing contributions to local theories on professionalisation processes (in this study specifically by completing the list of relevant categories and by hypothesising on typical starting points and pathways). The areas are intertwined in the sense that each cycle builds upon results of previous cycles across the areas.

Working areas of design research for teachers with a content-specific focus (Prediger et al. 2016)

Corresponding to the dual aims, design results and research results are equally important; the design results comprise the PD course settings and their backgrounds, a specified and structured PD content, and refined design principles. Research results include contributions to local theories, developed to underpin the concrete products and to be generalised by accumulation over several projects.

Methods of data gathering

Language context

All participating teachers in the study were volunteers in the PD courses and mostly monolingual Germans. At the time of the study, they taught secondary mathematics classes which often include more than 60% immigrants (under 2% newly arrived immigrants) and many mono- or multilingual students with limited academic language proficiency, but fluency in everyday German language (Prediger et al. 2018). German was the language of instruction; students’ home languages were usually permitted in group work.

Research context of the overarching project

The design research study is part of an overarching design research project in four design experiment cycles (see overview in Table 1).

Data gathering for the case studies in this article

The concrete case studies presented in this paper stem from the cycles with in-service teachers (Cycles 1, 2, and 4) and focus on one specific activity in the first PD session in which the design researcher was the facilitator herself.

The data corpus for the first case consists of students’ written products from one teachers’ classroom and the researchers’ diary from the PD session. Data for the other cases were collected in Cycles 2 and 4 by gathering teachers’ (n = 65) written products from a PD activity, by observing some teachers’ classrooms, and by video-recording teachers’ small-group and whole-group discussions during and after this activity in Cycle 4. Eight video-recorded small-group discussions of 25–50 min each were analysed for this article. The cases selected in this article were ones for which classroom observations were also available so that the interpretations could be triangulated.

Methods of data analysis for the concrete case studies

The teachers’ written products and transcribed small-group discussions were qualitatively analysed with respect to teachers’ activated categories while working on an activity for the jobs of SUPPORTING and IDENTIFYING language. The qualitative data analysis procedure followed three steps of inductive category-formation methods (Mayring 2015):

-

In Step 1, each teacher’s utterance was analysed using Vergnaud’s (1996, 1998) methodology for identifying individual and shared concepts-in-actions.

-

In Step 2, the identified concepts-in-action were systematically compared within and across individuals in order to inductively systematise them in a coherent language of categories. All categories are marked by “||…||” in order to outline their character as conceptual tools. Systematic comparison of cases revealed a landscape of potentially relevant categories in which the teachers’ learning pathways could be located. The categorical scheme that was inductively developed in cycle 1 was then used to deductively analyse in cycles 2 and 4 in order to capture what the teachers referred to and which connections and distinctions they made.

-

In Step 3, the 65 analysed written products were systematically compared and classified in order to identify typical cases to be presented in this article. There turned out to be five clearly distinguishable types of case under which all cases could by subsumed.

Results: empirical insights into teachers’ learning pathways towards language-responsive mathematics teaching

In order to provide empirical insights into teachers’ learning pathways, the section starts with a case study from Cycle 1 showing an example of absence of relevant categories. This case formed the base for a PD activity in later cycles, and also provided an occasion to investigate other teachers’ starting points on the jobs of SUPPORTING language and IDENTIFYING relevant language demands. The section identifies teachers’ typical categorical starting points for these jobs, and the section traces the learning pathway of one group of teachers.

Need for connecting jobs and introducing categories: the case of Martin Schreiber from Cycle 1

One case study from cycle 1 is briefly presented in order to show the importance of the job of IDENTIFYING language demands relevant for mathematics, a typical challenge that teachers face when introducing language responsiveness into their classrooms:

Reporting the case

Martin Schreiber (pseudonym), a monolingual middle school mathematics teacher, chose to participate in the CPD as he recognised the need to respond to the language diversity of his classes. By the second CPD session, he had adopted all intended orientations (see the “Disentangling teacher expertise for language-responsive mathematics teaching” section: He assumed responsibility for students’ diverse language learning, strived for pushing instead of reducing language, and tried to adopt integrative rather than additive strategies).

In order to realise them in his classrooms, Martin Schreiber experimented with the two jobs of DEMANDING and SUPPORTING language. After a teaching unit on the equivalence of fractions (see Fig. 3, 1st step), he posed a writing task with scaffolds in a list of useful phrases (Fig. 3, 2nd step). After conducting writing conferences in small groups, one model text was jointly developed in a whole-class discussion (3rd step) and then transferred to the second procedure of simplifying fractions in seatwork (4th step). He considered his teaching unit successful since all children could formulate a text similar to the one shown in Fig. 3 (4th step).

Martin Schreiber brought this experience and his students’ written products to the third PD session and asked his colleagues to NOTICE the students’ language in the written products. In the first minutes, the group (including Martin) assessed the texts only according to orthography, grammar errors (errors not translated to English in Fig. 3, 2nd step), and use of technical terms. The discussion did not assess whether the content goals had been achieved.

When the PD facilitator asked what the students’ products can tell about their conceptual understanding of equivalence of fractions, one teacher realised, “They do not write about it, only about how to calculate it”. Subsequently, the teachers started to reconsider the texts and articulate that most students only refer to the procedures. Now, other teachers recognised that the third text was an explanation: “‘Divide the fraction’ is not the right word, but the perfect idea for explaining the finer structure of the shaded amount”. It was only after this moment that the discussing teachers realised that the phrase list was only instrumental to reporting on formal procedures, but no help in explaining meanings. With the facilitators’ support, they started to collect other meaning-related phrases such as “finer partitioning of the rectangle.”

Analysing the case with respect to activated categories

The analysis of individually activated concepts-in-actions reveals an explanative account for the situation: in the first step, Martin Schreiber activates the two categories ||procedural knowledge|| and ||conceptual knowledge|| during the introduction of equivalence. Also, when DEMANDING language in the second step, he refers to both forms of knowledge in the writing task and asks for two ||discourse practices||, namely ||reporting procedures||, and ||explaining meanings|| of equivalence. However, in his scaffolding phrase list, he only offers words that support ||reporting procedures||. Consequently, the students only show ||reporting procedures||, and this reduction is maintained through the third and fourth step.

When first discussing the students’ products in the PD session, the teachers (including Martin) only activate categories for the surface of language, namely ||orthography||, ||grammar errors|| and the use of ||technical terms||. These activated categories do not enable them to assess whether the content goals have been achieved, as they cannot yet IDENTIFY the mathematically relevant language demands.

It is the PD facilitator’s question about students’ conceptual understanding of equivalence that prompts the teachers to shift from the surface level of language to the relevant ||discourse practices||. When they assess the students’ texts with respect to the categories of ||discourse practices||, they start to distinguish the two content goals of ||procedural knowledge|| on how to expand fractions and the ||conceptual knowledge|| about the meaning of equivalence of fractions. At this point, other teachers recognise that the third text shows ||explaining meaning||, which is relevant for the content goal of consolidating ||conceptual knowledge||. When the facilitator guides them back to the vocabulary, they start to see the vocabulary in its tight connection to the discourse practices, not as an end in itself but as ||lexical means|| for the ||discourse practices||.

From this analysis, it can be inferred that although Martin Schreiber has treated ||procedural and conceptual knowledge|| before the writing task, his language efforts are restricted to the ||discourse practice of reporting procedures||, for which he provides ||formal vocabulary|| support and which he optimises in the joint discussion. In contrast, addressing the ||conceptual knowledge|| requires the ||discourse practice of explaining meanings||, and this could have only been supported with more meaning-related phrases such as “the same share” and “structuring in a finer way.” But these meaning-related discourse practices and lexical means were not immediately IDENTIFIED as relevant and—although DEMANDED in the writing task—neither SUPPORTED nor NOTICED by the discussing teachers.

The brief analysis of this first case study shows how the different jobs are intertwined: teachers can only NOTICE and SUPPORT the language features that they have IDENTIFIED; for these jobs, they need adequate categories. Otherwise, they stay on the surface level of language (Prediger et al. 2018a). Several similar episodes during Cycle 1 led the researcher to include not only ||discourse level|| as relevant category in the PD, but to explicitly introduce the ||interplay of content goal and discursive practice|| and the ||interplay of discursive practice and lexical means||, as also emphasised by Short (2017). Figure 4 illustrates these identified categories and their connections, with the interplay between categories shown as horizontal arrows.

Design consequences: designing an activity for the PD courses in Cycle 2

With the permission of Martin Schreiber, his classroom documents were used in Cycle 2 of the design experiment to design an activity for further PD sessions in which other teachers could discover the strong connection between the different jobs and the relevance of ||discourse practices|| as the crucial category for IDENTIFYING mathematically relevant language demands and to construct the relevant connections between categories as indicated in Fig. 4. Figure 5 shows the designed activity in its final form (iteratively refined during five mini-cycles in Cycle 2).

The goal of the activity is to enhance teachers’ awareness of the necessary job of IDENTIFYING relevant language demands before SUPPORTING the writing task. Task 1 (in Fig. 5) asks the teachers to write a “dream text” on their own; the intent of this is to focus on the discourse practices and on a better choice of supporting phrases, drawn from the text for Task 2. Task 3 then asks the teachers to contrast their own supporting phrases with the pre-given ones (not yet visible in Tasks 1 and 2). This provides an occasion for teachers to experience a contrast between the pre-given, formal phrases and their own phrases that are hopefully more meaning related. On this base, they can discuss in which way students’ texts are influenced by teachers’ support.

As teachers often articulate their ideas in quite intuitive ways, a whole-group reflection in the end is necessary to connect their first intuitive articulations to the systematic categories of ||content goals||, ||discourse practices|| and ||lexical means|| and make explicit the necessary distinctions and interplays in a graphical organiser such as the one shown in Fig. 4. The necessary distinction of categories is symbolised by the vertical arrows between the lines and the interplays by the horizontal arrows between the columns.

Teachers’ typical starting points in the activity: comparing cases from Cycles 2 and 4

The later cycles were used to investigate teachers’ typical starting points while working on the job of IDENTIFYING language demands and SUPPORTING language in the PD activity in Fig. 5. For this, teachers’ (n = 65) written dream texts and supporting phrases were analysed and systematically compared in order to condense them to typical cases. As a result of this analysis, five typical cases are presented here to exemplify the differences found for the 65 teachers.

Reporting the cases

Figure 6 shows five typical teacher writings for the PD activity in Fig. 5 (all teacher names are pseudonyms, and all were monolingual teachers in multilingual classrooms with some years of teaching experience, and the teachers’ classroom practices in these classrooms were also observed). The left column shows their original writings (translated from German).

Analysis of cases

The right column of Fig. 6 shows the condensed results of the analysis, with the activated categories and interplays in each case mapped onto the landscape of Fig. 4 (in black letters and arrows). The navigation in the landscape then enables the researcher to infer a possible next step in the teacher’s mutual learning pathway for each case (in green letters and arrows).

Case 1: Tom Taylor’s immediate phrase list

Although Tom Taylor was asked to write an explanation, as he expected the students to do, he skipped this step and immediately collected technical terms for the phrase list: “numerator, denominator, expanding, multiply”. Like Martin Schreiber in the and many other teachers, he focused only on the ||word level|| and the ||formal vocabulary||, without taking into account other categories. The rationality behind this approach was extrapolated from many discussions: His supporting phrases comprised the terms on which he had focused in the last decades, i.e. the unfamiliar technical terms that the students need to be encouraged to use. A possible next step in the teachers’ learning pathway refers to the ||interplay of discourse practices and lexical means|| and then later the extension to ||meaning-related vocabulary||.

Case 2: Selma Zellers’ exclusive focus on procedures

Whereas Tom Taylor had not thought about discourse practices and the content goal when collecting the supporting phrases, Selma Zeller deliberately wrote a ||report on the procedure|| and chose corresponding support phrases only from the ||formal vocabulary||. The possible next step in her learning pathway should extend the content goals to ||conceptual knowledge|| and then the ||interplay to the discourse practices||. (For cases such as Selma and Tom, the students’ written text examples were complemented by an explanation of meaning in the activity sheet in Fig. 5.)

Case 3: Olivia Urk’s inconsistency

In contrast, Olivia formulated a comprehensive ||explanation of meaning|| (see Fig. 6). Interestingly, her support phrases still remained on the ||formal level|| and contained phrases that do not appear in her text. Although she connected the explanation to the conceptual learning goal, the support phrases were independent from this. Thus, the possible next step of her learning pathway should address the ||interplay between discourse practices and lexical means|| and the ||distinctions between meaning-related and formal vocabulary||.

Case 4: Sibylle Niehaus’s struggle with articulating explanations

Sibylle was very concerned with ||conceptual understanding|| (and often focuses on it in her classrooms by extensively working with visual models and graphical representations, as seen in classroom video-recordings). However, when asked to write an explanation, she struggled and said, “This task really brings me to my limit”. Like Sibylle, many of the deepest thinking teachers in our sample became aware that they had no specific goal in mind in terms of how they want their students to formulate explanations. They realised their own “speechlessness” and took it as a starting point for the next step in the learning pathway by reflecting independently on making the ||interplay of the discourse practice of explaining meanings and the underlying lexical means|| explicit to students by compared it to ||interplay of reporting procedures and the formal vocabulary||.

Case 5: Elisa Erikson’s mix of discourse practices and language means

Elisa combined both the discourse practices of ||reporting procedures|| and ||explaining meanings|| in her writing and even tried ||justifying the rule||. Accordingly, she collected supporting phrases from ||meaning-related vocabulary|| and ||formal vocabulary||. The next section will show how the discussion with her discussion partner enabled her to independently discover further categories and the relevance of the distinctions and the interplays.

Summing up, the analysis of these five cases shows that most teachers can activate some relevant resources for this activity in their first PD session, but do not yet activate categories required for realising the integrative-instead-of-additive orientation. In this way, their vocabulary support does not correspond to the original mathematical goal of supporting the consolidation of conceptual knowledge. This finding of one-sided starting points was also confirmed during other activities and observations of their classroom practices (Prediger 2019).

Tracing teachers’ typical pathways through the activity: the case of Elisa, Katja, and Sanne

The following episode shows not only teachers’ starting points that are made explicit by activities such as the one in the section but also a possible learning pathway that developed during a small-group discussion of three monolingual teachers, Elisa Erikson (case 5 from the previous section), Sanne Gerster, and Katja Ludwig. To trace their learning pathways with respect to the articulation of categories, the transcripts and the analysis are presented in an alternating pattern, sequence by sequence.

Like Elisa Erikson, her colleagues Sanne Gerster and Katja Ludwig have also written rich texts in which both discourse practices appear in a mixed form. Their phrase lists are also mixed, with both formal and meaning-related vocabulary (as was Elisa’s in Fig. 6). The transcript starts with Task 3 from Fig. 4, when they compare their own phrase lists with the list provided by Martin Schreiber. This comparison initiates their process of making distinctions and connections explicit:

6 Elisa I think I would start a step earlier. What it means.

[After considering the supporting phrases from purely formal vocabulary given by the teacher in Fig. 4.]

10 Sanne Eh? Well, I would have worked much more with the figure. Structuring, in a finer way.

In turn 6, Elisa starts the discussion by activating the distinction ||procedural vs. conceptual knowledge||, which was not visible in her written text (see Fig. 6) but elicited by the communication in the small group. Sanne joins her with similar ideas (in nonprinted turns 7–9). When first approaching the teachers’ given phrase lists, Sanne transfers this distinction to the lexical means and distinguishes (in turn 10) vocabulary that can be used for explaining meanings (→ ||meaning-related vocabulary||) from ||formal vocabulary||.

Having distinguished the content goals and the lexical means, the three teachers make explicit the ||interplay of specific discourse practices and lexical means|| in specific cases each (to increase the readability of the shortened transcripts, additional words marking explicit references were added in brackets):

13 Katja For describing [procedures] this [the formal vocabulary] is quite good.

14 Sanne For describing, yes. But with it, they [the students] do not see that they [the fractions] are equivalent.

15 Katja Yes, that’s right. But this [meaning-related] strategy, making it finer anyway, but it stays the same anyway. But this is much more difficult to put into words, yes. There [for the procedure of expanding] I can construct sentences more easily … Because I can simply formulate it concretely.

In Turn 13, Katja articulates the ||interplay of reporting procedures and formal vocabulary|| for the procedural utterances and generalises to both discourse practices in turn 15. Sanne connects it to the ||interplay of content goals and discourse practices|| in Turn 14 for both discourse practices when emphasising that the discourse practice ||reporting procedures|| does not support the content goal of acquiring ||conceptual knowledge||. Some turns later, they generalise the discovered distinctions and connections:

24 Sanne It just also depends on what is intended with the question. Is its aim how to calculate? Thus how to turn the 2/6 into 6/18. Or what does it mean?

34 Sanne What else do we have [reads out loud Task (3) from the activity sheet printed in Fig. 4]. Compare this phrase list with your list and justify what you refer. We justify. I believe it really depends on how you understand the question. Well, on what you put emphasis … on procedures [or on explaining meanings].

35 Elisa [writes for Task (3)]: Here, only a supporting phrase for the procedures is given, no support for the graphical representation. That’s why we prefer our “longer” list.

Even if still somewhat contextualised and implicit, Sanne articulates the interplay of ||content goals|| and ||discourse practices|| in Turn 24 and the interplay of ||discourse practices|| and ||lexical means|| in Turn 34. Finally, Elisa writes down the distinction of ||reporting procedures vs. explaining meanings|| and the interplay of ||content goals||, ||discourse practices||, and ||lexical means||.

Finally, the plenary discussion in which the landscape (printed in Fig. 4) was explicitly written on the whiteboard enabled the teachers to articulate their ideas using the terms offered by the facilitator.

The graphical summary in Fig. 7 resumes the analysis of these teachers’ pathways through the activity in which they articulate more and more explicitly the distinctions between the procedural and the conceptual content goals, discourse practices, and lexical means and also the interplay between the three categories. Thus, teachers’ learning pathways concerning activated categories can be described as a succession of inventions, refinements and connections of categories.

The fine-grained analysis in the case of Elisa, Katja, and Sanne has provided an insight into how some teachers can develop their positions by making explicit the categories and connections on their own: when they start with some intuitive distinctions of ||procedural knowledge|| and ||conceptual knowledge||, they can discover the connection to different discourse practices and become aware of their distinctions as well as the distinctions of ||vocabulary||. Similar processes have been observed for teachers with starting points such as Sibylle’s.

In contrast, teachers with starting points such as Tom’s, Selma’s and Olivia’s require an external input for reflection before they can develop their thinking. This external input is sometimes given by the small group they work with (like in the case of Selma); if not, it is the facilitator’s job to initiate further steps in the individual learning pathways.

Discussion and conclusion

Main achievements of the design research project and their embedding

Professionalising teachers for language-responsive mathematics teaching is a major challenge for achieving equity for language learners (Meaney et al. 2012). Although classroom research has revealed many aspects to be considered for fostering the mathematics learning of language learners (Moschkovich 2002, 2013; Prediger and Zindel 2017), more research is required to provide a research base for PD courses on language-responsive mathematics teaching (Adler 1995; Hajer and Norén 2017). Whereas general design principles for PD can be transferred from other PD research (Timperley et al. 2007), selecting concrete categories treated in the PD is still in the process of investigation. This article contributes to specifying what categories teachers must learn and how they can learn them for a specific part of the PD content, namely an activity of SUPPORTING students’ language and IDENTIFYING the language demands in mathematically relevant activities.

By initiating and investigating classroom-near PD activities, the presented design research study takes into account the call for situated conceptualisations of teacher expertise as embedded in teachers’ simulated practices (Blömeke et al. 2015; Depaepe et al. 2013). Zooming in on the microlevel of one activity enables the researcher to interpretatively reconstruct the challenges for teachers to fulfil the jobs of SUPPORTING and IDENTIFYING of a language-responsive mathematics teaching, simulated in a PD session: All teachers in our PD courses in Cycles 3 and 4 were quickly committed to three intended orientations. However, realising the integrated-instead-of-additive orientation in classrooms is difficult as long as the teachers restrict themselves and students to surface categories of language rather than categories in the conceptual domain (Adler 1995) and the connection between content goals, discourse practices, and lexical means (Short 2017).

The comparison of typical cases of starting points shows the explanative power of well-specified PD content: mapping each of the cases on the landscape of Fig. 4 provides the means to capture crucial similarities and differences. In this way, the comparison reveals the huge diversity of teachers’ starting points, which must be taken into account in facilitator’s moderation of the reflective discussions succeeding the small-group activity. These cases give hints about typical patterns in teacher learning: sometimes, teacher learning consists of extending the repertoire of categories for shifting the focus (as in Tom’s and Selma’s cases); in other cases, the teacher learning consists of making explicit intuitions that are already in teachers’ resources. These empirical insights have informed the refinement of the PD activities during three design research cycles.

Furthermore, the analysis of one microprocess in the case of Elisa, Katja, and Sanne provides a first (not yet generalizable) indication of how teachers with strong resources can develop their thinking by successively elaborating their categories. Although further analyses of other cases are required, this case provides a first hint that the PD activity achieved its goals, even if (evidently,) these processes do not immediately imply changes of classroom practices. However, stronger connections of categories seem to be a prerequisite for later changes of practices for IDENTIFYING language demands and SUPPORTING them.

In total, the analyses show the high relevance of the integrative-instead-of-additive orientation, which can only be realised by a functional linguistic perspective that subordinates the lexical dimension under the discursive dimension by considering vocabulary as a lexical means for discourse practices required to aim at mathematical content goals. The identified map of connections (in Fig. 4) is therefore a suitable elementarisation of deep linguistic ideas (Schleppegrell 2007; Snow and Uccelli 2009). With the epistemic function of language in mind, DEMANDING and SUPPORTING discourse practices should be grounded in choosing discourse practices relevant to a specific mathematical goal. For example, developing conceptual understanding requires the discourse practice of explaining meanings.

The major theoretical contribution of this article consists of tracing teacher’s pathways towards expertise for language-responsive mathematics teaching by reconstructing the ways they address the underlying categories and their interplays. Although far from being complete, the qualitative analysis on the micro-level of one activity reveals deep insights into teachers’ typical starting points and learning pathways when connecting the jobs and categories. In this way, the article provides a first contribution to reduce the research gap in the investigation of teachers’ learning processes that was stated by Goldsmith et al. (2014).

A necessary precondition for capturing teachers’ processes on the microlevel was the rich content-related conceptualisation of teacher expertise (Fig. 1). This conceptualisation reveals an opportunity to specify the expertise in language-responsive mathematics teaching in the interplay of jobs, orientations and categories. For the one core activity in view, the even finer specified PD content with its relations between categories served as the landscape in which the teachers’ starting points and pathways could be mapped (Fig. 4). This allowed the researcher to link dispositions and performances as requested by Blömeke et al. (2015). As in other design research studies on the student level, the fine-grained specification of the learning content is a precondition for tracing learning pathways.

The practical design outcome of the overarching design research study consists of thoroughly conceived PD materials with presentations, activity sheets, videos and handouts for facilitators that are available as open educational resources to all German mathematics facilitators. As facilitators never take PD materials without adaption, the handouts present theoretical backgrounds and insights into teachers’ learning pathways in order to inform the facilitators’ adaptations. This shows how research results and design results are intertwined.

Limitations of the study and next steps on the research agenda

The case studies were used to generate insights into typical learning pathways, starting points and obstacles for teachers in their approach towards expertise in language-responsive mathematics teaching. As in all design research studies (Cobb et al. 2003; Plomp and Nieveen 2013), these findings are still local in nature: local due to rather limited samples in the qualitative study, local as they are tied to the specific learning environment of the PD activities (which cannot yet account for changes in classroom practices), and local as they refer only to the specific PD content of language-responsive mathematics teaching.

Hence, different kinds of extensions are required in the next steps of the research agenda: in the next design experiment cycles, the sample size will be increased in order to test the generated hypothesis on typical pathways, conditions of success, and effects in a larger sample, also including quantitative measures. The transfer to other PD learning environments should be investigated by studying other PD activities within the same CPD program. Additionally, future studies should further investigate whether the conceptualisation of teacher expertise in Bromme’s model (Bromme 1992) is also suitable for content other than language-responsive teaching, PD settings other than CPD with intermediate experimentation phases, and PD systems other than the German system.

References

Adler, J. (1995). Dilemmas and a paradox: Secondary mathematics teachers’ knowledge of their teaching in multilingual classrooms. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(3), 263–274.

Austin, J. L., & Howson, A. G. (1979). Language and mathematical education. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 10(3), 161–197.

Bass, H., & Ball, D. L. (2004). A practice-based theory of mathematical knowledge for teaching. In W. Jianpan & X. Binyan (Eds.), Trends and challenges in mathematics education (pp. 107–123). Shanghai: East China Normal University Press.

Blömeke, S., Gustafsson, J.-E., & Shavelson, R. J. (2015). Beyond dichotomies: Competence viewed as a continuum. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 223(1), 3–13.

Bromme, R. (1992). Der Lehrer als Experte. Bern: Huber.

Bromme, R. (2001). Teacher expertise. In N. J. Smelser & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 15459–15465). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, S. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32–42.

Bunch, G. C. (2013). Pedagogical language knowledge: Preparing mainstream teachers for English learners in the new standards era. Review of Research in Education, 37(1), 298–341.

Byrnes, D. A., Kiger, G., & Manning, M. L. (1997). Teachers’ attitudes about language diversity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 13(6), 637–644.

Cobb, P., Confrey, J., diSessa, A., Lehrer, R., & Schauble, L. (2003). Design experiments in educational research. Educational Researcher, 32(1), 9–13.

Depaepe, F., Verschaffel, L., & Kelchtermans, G. (2013). Pedagogical content knowledge: A systematic review of the way in which the concept has pervaded mathematics educational research. Teaching and Teacher Education, 34(Supplement C), 12–25.

Echevarria, J., Vogt, M. E., & Short, D. (2010). The SIOP model for teaching mathematics to English learners. Boston: Pearson.

Ellerton, N., & Clarkson, P. (1996). Language factors in mathematics teaching and learning. In A. Bishop, M. A. K. Clements, C. Keitel-Kreidt, J. Kilpatrick, & C. Laborde (Eds.), International handbook of mathematics education (pp. 987–1033). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Empson, S. B., & Jacobs, V. J. (2008). Learning to listen to children’s mathematics. In T. Wood & P. Sullivan (Eds.), International handbook of mathematics teacher education (Vol. 1, pp. 257–281). Rotterdam: Sense.

Essien, A. A., Chitera, N., & Planas, N. (2016). Language diversity in mathematics teacher education: challenges across three countries. In R. Barwell, P. Clarkson, A. Halai, M. Kazima, J. Moschkovich, N. Planas, M. Setati-Phakeng, P. Valero, & M. Villavicencio Ubillús (Eds.), Mathematics education and language diversity (pp. 103–119). Cham: Springer.

Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning. Teaching second language learners in the mainstream classroom. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Goldsmith, L., Doerr, H., & Lewis, C. (2014). Mathematics teachers’ learning: A conceptual framework and synthesis of research. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 17(1), 5–36.

Grossman, P. L., Smagorinsky, P., & Valencia, S. (1999). Appropriating tools for teaching English: A theoretical framework for research on learning to teach. American Journal of Education, 108(1), 1–29.

Haag, N., Heppt, B., Stanat, P., Kuhl, P., & Pant, H. A. (2013). Second language learners’ performance in mathematics: Disentangling the effects of academic language features. Learning and Instruction, 28(0), 24–34.

Hajer, M. (2006). Inspiring teachers to work with content-based language instruction—Stages in professional development. In I. Lindberg & K. Sandwall (Eds.), Språket och kunskapen (pp. 27–46). Gothenburg: Institutet för Svenska som Andraspråk.

Hajer, M., & Norén, E. (2017). Teachers’ knowledge about language in mathematics professional development courses: From an intended curriculum to a curriculum in action. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(7b), 4087–4114.

Kunter, M., Baumert, J., Blum, W., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., & Neubrand, M. (2013). Cognitive activation in the mathematics classroom and professional competence of teachers. Results from the COACTIV Project. New York: Springer.

Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2013). Preparing linguistically responsive teachers: Laying the foundation in preservice teacher education. Theory Into Practice, 52(2), 98–109.

Lyon, E. G. (2013). What about language while equitably assessing science? Case studies of preservice teachers' evolving expertise. Teaching and Teacher Education, 32(Supplement C), 1–11.

Ma, L. (1999). Knowing and teaching elementary mathematics. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Marshman, M., Geiger, V., & Bennison, A. (Eds.). (2015). Mathematics education in the margins (Proceedings of the 38th annual conference of the Mathematics Education Research Group of Australasia). Sunshine Coast: MERGA.

Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical background and procedures. In A. Bikner-Ahsbahs, C. Knipping, & N. Presmeg (Eds.), Approaches to qualitative research in mathematics education (pp. 365–380). Dordrecht: Springer.

McLeman, L., Fernandes, A., & McNulty, M. (2012). Regarding the mathematics education of English learners: Clustering the conceptions of preservice teachers. Journal of Urban Mathematics Education, 5(2), 112–132.

Meaney, T., Trinick, T., & Fairhall, U. (2012). Collaborating to meet language challenges in indigenous mathematics classrooms. Dordrecht: Springer.

Moschkovich, J. (2002). A situated and sociocultural perspective on bilingual mathematics learners. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 4(2&3), 189–212.

Moschkovich, J. (2013). Principles and guidelines for equitable mathematics teaching practices and materials for English language learners. Journal of Urban Mathematics Education, 6(1), 45–57.

Pimm, D. (1987). Speaking mathematically. Communication in mathematics classrooms. London: Routledge.

Planas, N., & Schütte, M. (2018). Research frameworks for the study of language in mathematics education. ZDM Mathemastics Education, 50(6), 965–974.

Plomp, T., & Nieveen, N. (2013). Educational design research: Illustrative cases. Enschede: SLO, Netherlands Institute for Curriculum Development.

Prediger, S. (2019). Design-Research in der gegenstandsspezifischen Professionalisierungsforschung. In T. Leuders, E. Christophel, M. Hemmer, F. Korneck, & P. Labudde (Eds.), Fachdidaktische Forschung zur Lehrerbildung (pp. 11.34). Münster: Waxmann.

Prediger, S., & Zindel, C. (2017). School academic language demands for understanding functional relationships: A design research project on the role of language in reading and learning. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(7b), 4157–4188.

Prediger, S., Schnell, S., & Rösike, K.-A. (2016). Design research with a focus on content-specific professionalisation processes: The case of noticing students’ potentials. In S. Zehetmeier, B. Rösken-Winter, D. Potari, & M. Ribeiro (Eds.), Proceedings of the third ERME topic conference on mathematics teaching, resources and teacher professional development (pp. 96–105). Berlin: Humboldt University/HAL Archive.

Prediger, S., Wilhelm, N., Büchter, A., Gürsoy, E., & Benholz, C. (2018). Language proficiency and mathematics achievement—Empirical study of language-induced obstacles in a high stakes test, the central exam ZP10. Journal für Mathematik-Didaktik, 39(Supp. 1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13138-018-0126-3.

Prediger, S., Şahin-Gür, D., & Zindel, C. (2018a). Are teachers’ language views connected to their diagnostic judgments on students’ explanations? In E. Bergqvist, M. Österholm, C. Granberg, & L. Sumpter (Eds.), Proceedings of the 42nd Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education (Vol. 4, pp. 11–18). Umeå: PME.

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2007). The linguistic challenges of mathematics teaching and learning: A research review. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 23(2), 139–159.

Schoenfeld, A. H. (2010). How we think. A theory of educational decision making and its educational applications. New York: Routledge.

Secada, W. G. (1992). Race, ethnicity, social class, language and achievement in mathematics. In D. A. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (pp. 623–660). New York: MacMillan.

Short, D. J. (2017). How to integrate content and language learning effectively for English language learners. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(7b), 4237–4260.

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14.

Smit, J., & van Eerde, D. (2011). A teacher’s learning process in dual design research: Learning to scaffold language in a multilingual mathematics classroom. ZDM - Mathematics Education, 43(6–7), 889–900.

Smit, J., Bakker, A., Eerde, D. v., & Kuijpers, M. (2016). Using genre pedagogy to promote student proficiency in the language required for interpreting line graphs. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 28, 457–478.

Snow, C. E., & Uccelli, P. (2009). The challenge of academic language. In D. R. Olson & N. Torrance (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of literacy (pp. 112–133). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thürmann, E., Vollmer, H. J., & Pieper, I. (2010). Language(s) of Schooling: Focusing on vulnerable learners (Vol. 2). Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., & Fung, I. (2007). Teacher professional learning. Best evidence synthesis iteration. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Vergnaud, G. (1996). The theory of conceptual fields. In L. P. Steffe & P. Nesher (Eds.), Theories of mathematical learning (pp. 219–239). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Vergnaud, G. (1998). Toward a cognitive theory of practice. In A. Sierpinska & J. Kilpatrick (Eds.), Mathematics education as a research domain: A search for identity (pp. 227–241). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Weinert, F. E. (2001). Concept of competence: A conceptual clarification. In D. S. Rychen & L. H. Saganik (Eds.), Defining and selecting key competencies (pp. 45–65). Seattle: Hogrefe & Huber.

Zahner, W., Velazquez, G., Moschkovich, J., Vahey, P., & Lara-Meloy, T. (2012). Mathematics teaching practices with technology that support conceptual understanding for Latino/a students. Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 31(4), 431–446.

Zawojewski, J. S., Chamberlin, M., Hjalmarson, M. A., & Lewis, C. (2008). Designing design studies for professional development in mathematics education. In A. E. Kelly, R. Lesh, & J. Baek (Eds.), Handbook of design research methods in education (pp. 219–245). New York: Routledge.

Acknowledgements

I thank the reviewers and Rebekka Stahnke for their constructive comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Funding

The presented design research study has been conducted within the project MuM-innovation (funded by the BMBF-research grant no. 03VP02270) in the framework of DZLM, the German Center for Mathematics Teacher Education (funded by the German Telekom Foundation), with the great support of my PhD student Dilan Şahin-Gür.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Prediger, S. Investigating and promoting teachers’ expertise for language-responsive mathematics teaching. Math Ed Res J 31, 367–392 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-019-00258-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-019-00258-1