Abstract

Intensive immunosuppression has enabled liver transplantation even in recipients with preformed donor-specific antibodies (DSA), an independent risk factor for graft rejection. However, these recipients may also be at high risk of progressive multifocal encephalopathy (PML) due to the comorbid immunosuppressed status. A 58-year-old woman presented with self-limited focal-to-bilateral tonic-clonic seizures 9 months after liver transplantation. She was desensitized using rituximab and plasma exchange before transplantation and was subsequently treated with steroids, tacrolimus, and everolimus after transplantation for her preformed DSA. Neurological examination revealed mild acalculia and agraphia. Cranial MRI showed asymmetric, cortex-sparing white matter lesions that increased over a week in the left frontal, left parietal, and right parieto-occipital lobes. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of the cerebrospinal fluid for the JC supported the diagnosis of PML. Immune reconstitution by reducing the immunosuppressant dose stopped lesion expansion, and PCR of the cerebrospinal fluid for the JC virus became negative. Graft rejection occurred 2 months after immune reconstitution, requiring readjustment of immunosuppressants. Forty-eight months after PML onset, the patient lived at home without disabling deficits. Intensive immunosuppression may predispose recipients to PML after liver transplantation with preformed DSA. Early immune reconstitution and careful monitoring of graft rejection may help improve outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is an opportunistic infection of the central nervous system caused by the John Cunningham virus (JCV) (Berger et al. 2013). Although initially described in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), PML can also occur after solid organ transplantation (Molloy and Calabrese 2009). PML is rare following liver transplantation, with a reported incidence of 0.21–0.76% (Martinez and Ahdab-Barmada 1993; Bronster et al. 1995). The prognosis of non-HIV PML is poor, with an estimated life expectancy of three months (Bloomgren et al. 2012).

Donor-specific antibodies (DSA) are antibodies against the donor-derived human leukocyte antigen (HLA) (Demetris et al. 2016). Because DSA are an independent risk factor for graft rejection, liver transplantation with preformed DSA has been discontinued (Demetris et al. 2016). Intensive immunosuppression has recently enabled liver transplantation in recipients with preformed DSA; however, PML risk remains high for recipients due to the comorbid immunosuppressed status (Akamatsu et al. 2021). We describe a case of long-term survival from PML after liver transplantation for preformed DSA. This report provides insights into this potentially manageable complication of liver transplantation with preformed DSA.

Case report

A 58-year-old, right-handed woman underwent living-donor liver transplantation for decompensated alcoholic liver cirrhosis. She had performed DSA, was desensitized with rituximab, and had undergone plasma exchange before transplantation. The patient received methylprednisolone (4 mg/day), tacrolimus (3 mg/day), and everolimus (1.5 mg/day).

Nine months after liver transplantation, she was admitted to our hospital with self-limited focal-to-bilateral tonic-clonic seizures. On admission, a neurological examination revealed mild acalculia and agraphia. She had no history of headache, fever, infection, or vaccination. CD4-positive and CD8-positive T cell counts were 185/μL and 1383/μL, respectively.

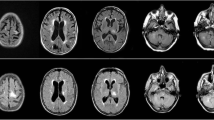

T2-weighted cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed asymmetric, cortex-sparing white matter lesions in the left frontal, left parietal, and right parieto-occipital lobes, with weekly enlargements. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted image showed partial enhancement in these brain lesions (Fig. 1A–C). Electroencephalography revealed repetitive spikes localized in the right parietal region (P4 max). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed no cells, a protein concentration of 33 mg/dL, an IgG index of 0.40, and positive oligoclonal IgG bands. JCV DNA was detected in the CSF using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (166 copies/mL) at the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (Tokyo, Japan). Epstein–Barr virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and varicella zoster virus were not detected by PCR. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid tests for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Cryptococcus, syphilis, and HIV were also negative.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the head. T2WI indicates T2-weigted image; T1-Gd, gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted image. T2-weighted image at the onset of progressive multifocal encephalopathy (PML) shows asymmetric, cortex-sparing white matter lesions in the left frontal and right parieto-occipital lobes (A). Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted image shows partial enhancement in these brain lesions (B). The lesions enlarge weekly, with a confluent pattern (C, 1 week after initial imaging; D, 3 weeks after initial imaging)

The patient fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for definite PML (Berger et al. 2013). Immune reconstitution was initiated before confirming the PCR findings. Tacrolimus was discontinued, and the methylprednisolone and everolimus doses were gradually tapered. There was no neurological deterioration, and the JCV DNA titer was reduced from 166 to 18 copies/mL 1 week after initiating immune reconstitution. As the lesions enlarged, the treatment was switched from prednisolone and everolimus to cyclosporine alone (50 mg/day) (Fig. 1D). Mirtazapine (15 mg/day) and mefloquine (275 mg/week) were administered after approval from the institutional ethics committee. Three weeks after initiating immune reconstitution, lesion expansion ceased. Monthly tests for JCV DNA in the CSF were also negative. There was no evidence of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

Two months after initiating immune reconstitution, aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels increased to 40–60 IU/L. Liver biopsy revealed portal inflammation with lymphocytes and eosinophils, bile duct damage, and endothelialitis with bile ductular proliferation. C4d immunohistochemical staining was positive in the portal veins. Acute cellular and antibody-mediated rejection was suspected. Her immunosuppressant dose was gradually increased to 2 mg/day methylprednisolone, 1.5 mg/day everolimus, and 75 mg/day cyclosporine, with close monitoring of neurological symptoms and MRI. Subsequently, her AST and ALT levels normalized with no PML relapse.

Forty-eight months after PML onset, she lived at home with an Expanded Disability Status Scale score of 1.5. MRI performed every 6 months showed no lesion enlargement. She remained negative on PCR for CSF JCV for over 3 years and 7 months (16 PCR tests). Graft dysfunction was not observed.

Discussion

We describe a case of long-term survival following PML in a liver transplant recipient with preformed DSA. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of preformed DSA among post-liver transplant patients with PML in the PubMed database (Table 1).

In Japan, liver transplantations from brain-dead donors remain low. The alternative option is living-donor liver transplantation, often with organs donated by their relatives. However, due to HLA similarity, the recipient is likely to have DSA and be at high risk of rejection (Yoshizawa et al. 2013). Intensive immunosuppression mitigates the risk of rejection, but it may also increase the risk of PML due to the comorbid immunosuppressed status (Yoshizawa et al. 2013). Among immunosuppressants, rituximab remains high-risk factor for PML (Clifford et al. 2011). Patients with liver cirrhosis without overt immunosuppression may develop PML (Gheuens et al. 2010). Desensitization in renal transplants is not associated with JCV viremia (Toyoda et al. 2015). However, they did not evaluate CSF, and the results may not be extrapolated to liver transplantation. PML should be considered a neurological complication in liver transplant recipients with DSA.

Long-term survival of patients with PML after liver transplantation has rarely been reported. Eighty percent of patients with post-liver transplant PML died within a median time of 5 months from diagnosis to death (interquartile range, 2–23 months) (Table 1). In non-HIV-PML, immune reconstitution in the early phase is linked to favorable outcomes (Amend et al. 2010). However, tapering immunosuppressant poses a dilemma for graft rejection in patients with PML after organ transplantation. Since the initial immunosuppressive dose reduction alone was not sufficient to stop the lesion expansion completely, we tried mirtazapine and mefloquine. It should be noted, however, that there is no evidence for the efficacy of these drugs, and there is an opposing viewpoint that they may only expose the patient to unnecessary side effects (Clifford et al. 2013). In post-liver transplant PML, rejection may be more likely to occur in DSA-positive cases than in DSA-negative cases, among which rejection occurred in 20% of the patients during PML treatment (Table 1).

In conclusion, intensive immunosuppression by preformed DSA may predispose recipients to PML after liver transplantation. Early immune reconstitution and careful monitoring of graft rejection may improve outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Akamatsu N, Hasegawa K, Sakamoto S, Ohdan H, Nakagawa K, Egawa H (2021) Rituximab desensitization in liver transplant recipients with preformed donor-specific HLA antibodies: a Japanese nationwide survey. Transplant Direct 7:e729. https://doi.org/10.1097/TXD.0000000000001180

Amend KL, Turnbull B, Foskett N, Napalkov P, Kurth T, Seeger J (2010) Incidence of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients without HIV. Neurology 75:1326–1332. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f73600

Berger JR, Aksamit AJ, Clifford DB, Davis L, Koralnik IJ, Sejvar JJ, Bartt R, Major EO, Nath A (2013) PML diagnostic criteria: consensus statement from the AAN Neuroinfectious Disease Section. Neurology 80:1430–1438. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828c2fa1

Bloomgren G, Richman S, Hotermans C, Subramanyam M, Goelz S, Natarajan A, Lee S, Plavina T, Scanlon JV, Sandrock A, Bozic C (2012) Risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med 366:1870–1880. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1107829

Bronster DJ, Lidov MW, Wolfe D, Schwartz ME, Miller CM (1995) Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl Surg 1:371–372. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.500010606

Clifford DB, Ances B, Costello C, Rosen-Schmidt S, Andersson M, Parks D, Perry A, Yerra R, Schmidt R, Alvarez E, Tyler KL (2011) Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol 68:1156–1164. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2011.103

Clifford DB, Nath A, Cinque P, Brew BJ, Zivadinov R, Gorelik L, Zhao Z, Duda P (2013) A study of mefloquine treatment for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: results and exploration of predictors of PML outcomes. J Neurovirol 19:351–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-013-0173-y

Demetris AJ, Bellamy C, Hübscher SG, O’Leary J, Randhawa PS, Feng S, Neil D, Colvin RB, McCaughan G, Fung JJ, Del Bello A, Reinholt FP, Haga H, Adeyi O, Czaja AJ, Schiano T, Fiel MI, Smith ML, Sebagh M, Tanigawa RY, Yilmaz F, Alexander G, Baiocchi L, Balasubramanian M, Batal I, Bhan AK, Bucuvalas J, Cerski CTS, Charlotte F, de Vera ME, ElMonayeri M, Fontes P, Furth EE, Gouw ASH, Hafezi-Bakhtiari S, Hart J, Honsova E, Ismail W, Itoh T, Jhala NC, Khettry U, Klintmalm GB, Knechtle S, Koshiba T, Kozlowski T, Lassman CR, Lerut J, Levitsky J, Licini L, Liotta R, Mazariegos G, Minervini MI, Misdraji J, Mohanakumar T, Mölne J, Nasser I, Neuberger J, O’Neil M, Pappo O, Petrovic L, Ruiz P, Sağol Ö, Sanchez Fueyo A, Sasatomi E, Shaked A, Shiller M, Shimizu T, Sis B, Sonzogni A, Stevenson HL, Thung SN, Tisone G, Tsamandas AC, Wernerson A, Wu T, Zeevi A, Zen Y (2016) 2016 comprehensive update of the Banff working group on liver allograft pathology: introduction of antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant 16:2816–2835. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.13909

Gheuens S, Pierone G, Peeters P, Koralnik IJ (2010) Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in individuals with minimal or occult immunosuppression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 81:247–254. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2009.187666

Martinez AJ, Ahdab-Barmada M (1993) The neuropathology of liver transplantation: comparison of main complications in children and adults. Mod Pathol 6:25–32

Molloy ES, Calabrese LH (2009) Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: a national estimate of frequency in systemic lupus erythematosus and other rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum 60:3761–3765. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24966

Toyoda M, Thomas D, Ahn G, Kahwaji J, Mirocha J, Chu M, Vo A, Suviolahti E, Ge S, Jordan SC (2015) JC polyomavirus viremia and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in human leukocyte antigen-sensitized kidney transplant recipients desensitized with intravenous immunoglobulin and rituximab. Transpl Infect Dis 17:838–847. https://doi.org/10.1111/tid.12465

Yoshizawa A, Egawa H, Yurugi K, Hishida R, Tsuji H, Ashihara E, Miyagawa-Hayashino A, Teramukai S, Maekawa T, Haga H, Uemoto S (2013) Significance of semiquantitative assessment of preformed donor-specific antibody using Luminex single bead assay in living related liver transplantation. Clin Dev Immunol 2013:972705. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/972705

Funding

Open access funding provided by The University of Tokyo. This work was supported by the Research Committee of Prion Disease and Slow Virus Infection, Research on Policy Planning and Evaluation for Rare and Intractable Diseases, Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants, The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan (grant nos. 20FC0201 and 23FC1007), and JSPS KAKENHI (grant no. 21K07450).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of this study. Shuhei Egashira and Risa Kotani performed material preparation, data collection, and analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Shuhei Egashira, and all authors commented on previous versions. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Egashira, S., Kubota, A., Kakumoto, T. et al. Long-term survival from progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in living-donor liver transplant recipient with preformed donor-specific antibody. J. Neurovirol. 29, 519–523 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-023-01171-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-023-01171-x