Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is rapidly reaching epidemic status among a burgeoning aging population. Much evidence suggests the toxicity of this amyloid disease is most influenced by the formation of soluble oligomeric forms of amyloid β-protein, particularly the 42-residue alloform (Aβ42). Developing potential therapeutics in a directed, streamlined approach to treating this disease is necessary. Here we utilize the joint pharmacophore space (JPS) model to design a new molecule [AC0107] incorporating structural characteristics of known Aβ inhibitors, blood-brain barrier permeability, and limited toxicity. To test the molecule’s efficacy experimentally, we employed ion mobility mass spectrometry (IM-MS) to discover [AC0107] inhibits the formation of the toxic Aβ42 dodecamer at both high (1:10) and equimolar concentrations of inhibitor. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) experiments reveal that [AC0107] prevents further aggregation of Aβ42, destabilizes preformed fibrils, and reverses Aβ42 aggregation. This trend continues for long-term interaction times of 2 days until only small aggregates remain with virtually no fibrils or higher order oligomers surviving. Pairing JPS with IM-MS and AFM presents a powerful and effective first step for AD drug development.

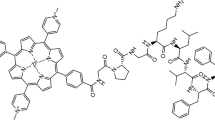

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disorder. The economic cost of care in the USA is projected to be $1.1 trillion per year by 2050, which is nearly a 4-fold increase over estimates for 2017 [1], and this cost does not include the millions of voluntary caregivers. The cause of AD is not fully understood and there is neither a cure nor therapy to slow the progress of the disease.

AD is correlated unequivocally post-mortem by the presence of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau protein as well as extracellular amyloid plaques in the brain. These plaques are composed of proteinaceous fragments of the neuronal transmembrane amyloid precursor protein (APP). There is increasing evidence that these fragments, collectively referred to as amyloid-beta (Aβ), are central to AD pathology, including inducing aberrant tau morphology [2,3,4]. Aβ is formed when APP is proteolytically cleaved by a series of secretases, leaving behind peptides primarily 40 and 42 residues in length, Aβ40 and Aβ42, respectively [5, 6]. Both alloforms self-associate in the extracellular space and form soluble oligomers that aggregate into insoluble amyloid fibrils. Interestingly, Aβ42 is ten times less prevalent in the brain than Aβ40, but is more fibrillogenic, much more toxic, and makes up the bulk of the amyloid plaques observed with AD [7,8,9,10,11,12]. A study of transgenic 3xTg-AD mice noted that significant extracellular accumulation of β-sheet-rich Aβ corresponded to appreciable intracellular uptake of Aβ along with cognitive deficits [12]. A neuroblastoma cell study of Aβ42 aggregation on the plasma membrane produced an analogous observation of increased cytotoxicity with internalization of Aβ42 aggregates in the intracellular domain [13]. Although large assemblies could be responsible, in part, to neurodegeneration in later stages of AD, a high plaque burden in the brain does not directly correlate with greater cognitive deficits [14,15,16]. Aβ fibrils may indeed be a kind of neuroprotective sink in the aggregation pathway compared to the penultimate, toxic soluble oligomers [17, 18].

Fibril morphology and aggregation mechanisms are quite different for Aβ40 and Aβ42, despite both having identical sequences save for Aβ42’s two additional C-terminal residues as shown in Scheme 1.

Aβ40 aggregation has been shown to terminate at tetramer, before going on to slowly form fibrils, but Aβ42 has growth out to dodecamer [19, 20]. A 56-kDA Aβ assembly linked to memory deficits in transgenic mice, and isolated in human cerebrospinal fluid, corresponds to the molecular weight of the Aβ42 dodecamer [9, 10, 17]. While the fibrils of Aβ42 are a significant neuropathological event in AD, atomic force microscopy (AFM) experiments showed the dodecamer of Aβ42 is vital for the initiation and seeding of fibril growth [21]. Hence, the dodecamer of Aβ42 plays a central role in AD and the inhibition of this soluble dodecamer species is key in preventing its inherent toxicity as well as subsequent pathological aspects of AD downstream.

Efforts to develop therapeutics to decrease or stop overall Aβ production by limiting secretase activity have proven unmanageable. As is typical for proteins, γ-secretase has important biological functions other than forming the C-terminus of Aβ, so altering its activity leads to reduction of neuronal calcium signaling, a decrease in lymphocyte production, and affects intestinal goblet cell differentiation [22,23,24]. β-Secretase, which cleaves APP to form the N-terminus of Aβ, has a large catalytic pocket that would require an inhibitor too large to effectively pass the blood-brain barrier [25]. Another strategy has been to upregulate Aβ clearance mechanisms through immunotherapy, but the development of meningoencephalitis, Aβ antibody-induced cerebral hemorrhages in transgenic mice and human trials [26,27,28], small population datasets, and very few completed phase III drug studies for immunotherapeutics has prevented significant progress [29]. Further, removing Aβ could impair neuroprotective properties of Aβ40 and inherent amounts of Aβ in the hippocampus [30,31,32,33], suggesting that oligomeric forms of Aβ are a more amenable target for AD therapeutics.

Many compounds are known to inhibit Aβ oligomeric growth and fibril formation [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] but finding a potential therapeutic drug with biological efficacy is extremely challenging. Currently, only a handful of drugs are FDA approved to treat AD and even fewer to treat all stages of it. One underlying factor slowing the development of therapeutics is that the detailed mechanism of AD pathology is not known. Consequently most efforts only aim to address symptoms of the disease to make it more manageable. Three immediate concerns with prospective anti-amyloid therapeutics are the compounds’ ability to pass the blood-brain barrier, toxicity to other bodily systems, and Aβ42 specificity. It is therefore of keen interest to find a directed approach for screening potential inhibitors of pre-fibril amyloid aggregation that also incorporate these concerns before the long and expensive processes of drug trials are initiated.

Utilization of the joint pharmacophore space (JPS) model [47, 48] to find potential therapeutics provides an in silico, first step in the drug discovery process. By accessing data on millions of compounds from cell-based assays, a database can be constructed for any attribute of a compound and then overlap those results with any number of other qualities from other assays. A machine-learning algorithm then constructs a list of compounds ranked by probabilistic methods for the most positive hits for all the qualities desired. Because the detailed mechanism of AD is not understood, it is important to emphasize that this approach does not single out one particular biological target. It takes into account a compound’s overall geometry of functional groups relative to other structural characteristics that have satisfied blood-brain permeability, low toxicity, and interaction with Aβ42 with no specific target in mind. Using these criteria, JPS can design new compounds that are more likely to have a directed impact on pathological aspects of AD.

To test this process experimentally, we have employed ion mobility mass spectrometry (IM-MS) and AFM to study the effect one high-scoring JPS generated compound [AC0107] (Scheme 2) has on Aβ42 assembly as well as its ability to remodel pre-formed Aβ42 fibrils.

Methods

Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry Experiments

Aβ42 wild-type peptides were synthesized by FMOC chemistry, purified by reverse-phase HPLC, verified through mass spectrometry and amino acid analysis as previously described [49], and lyophilized. Bulk peptides were subsequently dissolved in hexafluoroisopropanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis), aliquoted to individual vials, lyophilized again, and stored at − 20 °C. Prior to ion mobility experiments, peptides were solvated with 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 7.4) to a final peptide concentration of 10 μM. To prevent rapid aggregation and to increase ion signal, samples were kept on ice for the duration of the study. To study the effect of the inhibitor on Aβ42 assembly, mass spectra and arrival time distributions (ATDs) were collected first of Aβ42 alone and then inhibitor ([AC0107] provided by Acelot, Inc.) was added to the same solution to form a 1:10 peptide:inhibitor concentration ratio and the data was collected again. The same recovery experiment was carried out for a 1:1 concentration ratio as well. Incubation times indicate the time after solvation of Aβ42 at which signal was acquired during repeat experiments.

All ion mobility and mass spectrometry experiments were performed on a home-built electrospray ionization ion mobility mass spectrometer [50]. To acquire a mass spectrum, ions are generated via an applied potential difference between a gold-coated nanoelectrospray glass capillary tip and the capillary inlet of the mass spectrometer. The ions then travel through an ion funnel and are then injected into a 4.503-cm drift cell filled with ~ 3.5 Torr helium. Upon leaving the drift cell, ions are mass analyzed by a quadrupole mass filter and detected by a conversion dynode and channel electron multiplier.

For mobility experiments, ions are stored in the ion funnel and then pulsed at regular intervals into the drift cell at low energy. Once inside, ions travel through a helium buffer gas under the influence of a weak, homogeneous electric field, E. The ions quickly come to thermal equilibrium and reach a constant drift velocity, vd. Higher order oligomers have more charge and more compact component monomer cross-sections than those of a lower order and travel more quickly through the drift cell at constant pressure. The mobility is obtained from Eq. (1):

The ion mobility is dependent on both pressure and temperature and is converted to its reduced form:

with pressure P in Torr and temperature T in Kelvin.

The reduced mobility is determined by plotting the arrival time versus P/V ratio, where V is the voltage across the cell. The arrival time ta is given in Eq. (3):

where L is the drift cell length and t0 the time the ions spend outside the drift cell before reaching the detector.

After leaving the drift cell, ions are mass-selected and detected as a function of the arrival time to produce an arrival time distribution (ATD). An ion’s mobility is related to its collision cross-section σ as shown in Eq. (4) [51]:

where μ is the reduced mass of the ion and helium buffer gas, k the Boltzmann constant, e the charge of the ion, and N0 the buffer gas density.

AFM Experiments

Samples were prepared for AFM experiments by depositing 50 μL of 10 μM Aβ42 prepared in a 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer with the stated concentration of inhibitor onto freshly cleaved V1-grade mica (TedPella, Redding, CA) and dried in a desiccator. Tapping-mode AFM images were acquired from the dried samples in air using an MFP-3D Atomic Force Microscope (Asylum Research, Goleta, CA). High-resolution silicon probe tips with a tip radius of 1 nm, a cantilever spring constant of 7 N/m, and a resonant frequency of 155 kHz (MikroMasch USA, Lady’s Island, SC) were used to acquire the AFM images. All AFM images were collected in the repulsive force regime.

JPS In Silico Model

To train the JPS, a collection of 30 known Aβ inhibitors [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] were used to better recognize chemical topologies necessary for Aβ inhibition. With the JPS trained, the ZINC collection [52] was screened for compounds that incorporated structures more likely to inhibit Aβ self-assembly that also exhibited blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability and minimal toxicity. A shortlist of compounds was populated and then subjected to Caco-2 and hERG assays to give preliminary BBB permeability and toxicity information. The remaining compounds were subjected to a sensitive trafficking assay [53, 54] to test their ability to inhibit membrane trafficking of Aβ. [AC0107] is the first of the JPS-generated compounds to be tested experimentally.

Results and Discussion

IM-MS Experiments

Three peaks are present in the mass spectrum for Aβ42 wt alone: an electrospray-induced, monomer charge state z/n = −4, a monomer solution state z/n = −3, and an oligomer peak at z/n = −5/2 (Figure 1a) (all monomer z/n data is provided in the Supporting Information). Upon addition of the inhibitor, the same charge states are observed, with no complex peak formation for either 1:10 or 1:1 concentrations (Figure 1b, c). Even though there is no apparent binding of the inhibitor to Aβ42 in the mass spectrum, the ATD of the −5/2 peak is very different (Figure 1d–h). Prior to addition of inhibitor, we observe the same oligomeric structures previously assigned as dimer, tetramer, hexamer, decamer, and dodecamer (n = 2, 4, 6, 10, and 12, respectively) [19, 20]. After 1 h co-incubation with 1:10 inhibitor, the decamer and dodecamer ATD features are essentially eliminated.

(a–c) Representative mass spectra for Aβ42 alone, Aβ42 + 1:10 [AC0107], and Aβ42 + 1:1 [AC0107], respectively. (d) z/n = −5/2 ATD for Aβ42 alone. (e, f) z/n = −5/2 ATDs at 1 h co-incubation with 1:10 and 1:1 [AC0107], respectively. (g, h) z/n = −5/2 ATD at 24 h co-incubation with 1:10 and 1:1 [AC0107], respectively. The injection energy for each ATD is 40 V. Each ATD has fitted structures with labels corresponding to Aβ42 dodecamer (n = 12, purple fit), decamer (n = 10, orange fit), hexamer (n = 6, green fit), tetramer (n = 4, red fit), and dimer (n = 2, blue fit). The peak fitting procedure is outlined in the Supporting Information

At 1 h, the hexamer peak is also significantly diminished with the tetramer and dimer features unchanged. At 24 h 1:10 co-incubation, the dodecamer disappears completely with oligomerization up to hexamer still present.

The same set of experiments were performed at a lower 1:1 Aβ42:[AC0107] ratio (Figure 1c, f, h). After 1 h co-incubation under these conditions, all oligomers of order n > 6 are completely inhibited. At 24 h 1:1 co-incubation, there is an increase in hexamer and decrease in dimer relative to the tetramer feature, but the dodecamer peak is still absent indicating [AC0107] prevents the dodecamer from forming.

We observe similar Aβ42 wt monomer cross-sections as previously published [19, 55, 56] both with and without the inhibitor (Table 1). This indicates that introduction of [AC0107] does not affect Aβ42 native monomer structure in our experiments (Fig. S1, S2). Interestingly, binding of the inhibitor to Aβ42 of any charge state is not observed. It is possible that the binding of the compound to full-length Aβ42 is not sustained under the conditions of the electrospray process, but clearly the disruption of cytotoxic oligomers of Aβ42 in solution is occurring.

AFM Experiments

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was utilized to study the effect of the inhibitor on the formation of larger scale aggregates and to determine the effect it may have on pre-formed aggregates and fibrils. A 50 μL aliquot of 10 μM Aβ42 solution in 10 mM ammonium acetate was removed and drop-cast onto a mica disc, dried at ambient conditions in a desiccator, and imaged. It takes approximately 5 min to prepare the peptide and for the disc to dry, making it the earliest time Aβ42 aggregation can be observed. After 5 min incubation, large globular aggregates have formed but few fibrils are observed (Figure 2a). By 30 min, fibril features emerge along with higher order oligomers (heights of 2–6 nm) (Figure 2b). After 60 min, the trend toward higher fibril content and larger oligomers continues (Figure 2c). The rapid formation of plentiful fibrils and globular aggregates is consistent with AFM studies at high concentration [57]. Particle height distributions (Fig. S3) show quantitatively what is shown visually in the AFM topography images. Over time, the ratio of higher order oligomers to lower order oligomers (particle heights less than 1 nm) increases with an overall decrease in the number of particles present. This can be attributed to smaller oligomers converting into larger ones and larger oligomers going on to form fibrils.

AFM height images for representative 10 μM Aβ42 incubated alone at room temperature in solution for (a) 5, (b) 30, and (c) 60 min. At 60 min, [AC0107] was added to the same solution of Aβ42 to a final concentration of 1:10 [AC0107] with aliquots taken and imaged at (d) 5, (e) 30, and (f) 60 min co-incubation. (g), (h), and (i) are 5, 30, and 60 min co-incubation times, respectively, for 1:1 Aβ42:[AC0107] concentration after 60 min of Aβ42 incubated alone. Each image is 2 × 2 μm in dimension. Lighter colors are taller structures with the darkest representing the mica background surface. Particle height distributions are included in the Supporting Information

Data for a 10-fold excess of inhibitor added to the same solution of pre-incubated Aβ42 are shown in Figure 2d–f. After 5 min with [AC0107], the AFM image (Figure 2d) is morphologically similar to Aβ42 alone at 60 min, but by 30 min co-incubation, there is a massive shift toward small oligomeric structures relative to large aggregates (Figure 2e) and after 60 min a peptide film is observed on the mica disc and few fibrils and distinct oligomeric features persist (Figure 2f).

The same AFM experiment was repeated at a lower 1:1 Aβ42:[AC0107] concentration ratio. After 5 min of co-incubation with the inhibitor, the pre-formed fibrils are still well established but by 30 min fibrils are diminished, indicating that [AC0107] is still effective at interrupting Aβ42 self-assembly at low concentrations (Figure 2h). The particle height distribution for the 30-min image results in a surprising decrease in low-order oligomers (heights less than 1 nm) relative to higher order ones. What is likely happening is the disaggregating effect of [AC0107] continues but lower order oligomers self-associate into a film with higher order structures depositing on top of them, showing an apparent decrease in lower order oligomers. These trends are sustained for the 60-min image (Figure 2i) with the continued breakup of pre-formed fibrils and the decrease in apparent number of lower order oligomers, both in support of [AC0107] as an effective inhibitor of Aβ aggregation.

Interpretation of AFM phase imaging sheds light on compositional characteristics of deposited material on the mica surface. Phase shifts of the oscillating cantilever as the AFM probe scans the features on the mica surface provide information about the energy dissipation when the probe tip interacts with the sample. When the probe interacts with particles that are hard (i.e., more structured), less energy is dissipated resulting in a phase shift toward 90° relative to the background media of the image. When the probe interacts with particles that are soft (less structured), more energy is dissipated and the phase shifts away from 90° relative to the background media of the image. We will use this rationale as a measure of the internal order of the amyloid fibrils on the mica surface. Variance in phase signal is commonplace among different samples and probes, but the observed phase shifts relative to structures within the image are consistent [58,59,60]. Figure 3a–c shows phase images of Aβ42 incubated in solution for 5, 30, and 60 min, respectively. As expected, the axes of the fibrils smoothen and are hard (i.e., ordered) relative to the background indicating fibril stability increases over time. Fewer distinct oligomeric assemblies are present as fibrils grow and lengthen (Figure 3c). Upon introduction of 1:1 inhibitor to the same solution, the fibril axis adopts a beads-on-a-string appearance, softens relative to the ordered fibrils, distinct oligomeric features become more represented, and the negative phase shift relative to the background has disappeared after the 60 min co-incubation (Figure 3d–f), similar to the peptide film observed at 1:10 [AC0107] at the same time point (Figure 2f). Through our IM-MS experiments, we verified that higher order oligomer (Aβ42 dodecamer) formation is being disrupted in the presence of [AC0107] (Figure 1). Here we observe a phase shift from harder to softer structures, and given that there is no reason to believe that monomers and lower order oligomers would normally get softer over time, it is reasonable that the internal order of the fibrils is becoming less structured due to the presence of [AC0107]. These data indicate [AC0107] destabilizes and reverses normal Aβ42 fibril assembly and encourages Aβ42 to behave more like the less cytotoxic Aβ40.

AFM phase images of 10 μM Aβ42 alone at (a) 5, (b) 30, and (c) 60 min incubation in solution. After 60 min, an equimolar 1:1 Aβ42:[AC0107] solution was achieved in the same solution and aliquots were removed and imaged at (d) 5, (e) 30, and (f) 60 min co-incubation. Relative to background media of the image, darker colors are physically harder and more structured than the surrounding material. Lighter colors are softer and less structured. Each image is 500 nm × 500 nm

To assess the steady state of Aβ42 aggregation in the presence of the [AC0107], the two were pre-mixed and incubated for 24 and 48 h and analyzed by AFM. At 24 h, there is little to no discrete oligomeric structures present (Figure 4a) though there are fully developed fibrils with 7 nm diameters, either alone or bundled together. This indicates that fibril formation is possible even in the presence of [AC0107] but it must occur by another pathway outside the dodecamer seeding mechanism [21] because dodecamer formation is completely inhibited shortly after addition of [AC0107] to Aβ42 solution as seen in our IM-MS experiments. Zooming in on both backgrounds of the 1:10 and 1:1 24 h images (Figure 4b, e, respectively), we can see a somewhat filamentous network of 1-nm tall structures, strikingly similar to what was observed with Aβ40 incubated at 30+ min [21]. At 48 h incubation with [AC0107], the fibril content is essentially zero for both 1:10 and 1:1 concentration ratios (Figure 4c, f, respectively). Interestingly, even the peptide film observed at earlier time points has broken up into discrete aggregates.

Conclusions

Aβ42 adopts a planar hexamer ring structure that stacks on another hexamer to form the toxic, stacked dodecamer species [19]. Amyloid inhibitors are thought to interrupt π-π stacking of aromatic chains that contribute to β-sheet structure as aggregation progresses [61,62,63]. It is possible [AC0107] acts this way as well. However, because no complexes of Aβ42 and [AC0107] are observed in our study, the details of the molecular interaction between Aβ42 and [AC0107] remain unclear.

Our data indicate [AC0107] initiates a reversal of the aggregation pathway of Aβ42 over the timescale of our experiments, interrupting the formation of Aβ42 higher order oligomers. AFM experiments show Aβ42 assembly in mixtures with [AC0107] behaves like the neuroprotective alloform Aβ40. This work supports the fact that Aβ42 dodecamers are critical to the rapid fibrillization of Aβ42. These results indicate the small molecules designed by JPS are effective and set the stage for a more cost-effective and direct screening strategy to combat AD.

Change history

11 February 2019

In this issue, the citation information on the opening page of each article PDF is incorrect. It should read ?Journal of the American Society of Mass Spectrometry (2019)?,? not ?Journal of the American Society of Mass Spectrometry (2018)...?

11 February 2019

In this issue, the citation information on the opening page of each article PDF is incorrect. It should read ���Journal of the American Society of Mass Spectrometry (2019)���,��� not ���Journal of the American Society of Mass Spectrometry (2018)...���

11 February 2019

In this issue, the citation information on the opening page of each article PDF is incorrect. It should read ���Journal of the American Society of Mass Spectrometry (2019)���,��� not ���Journal of the American Society of Mass Spectrometry (2018)...���

References

2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 13 (4), 325–373

Götz, J., Chen, F., van Dorpe, J., Nitsch, R.M.: Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301L tau transgenic mice induced by Aβ42 fibrils. Science (New York, N.Y.). 293(5534), 1491 (2001)

Lewis, J., Dickson, D.W., Lin, W.-L., Chisholm, L., Corral, A., Jones, G., Yen, S.-H., Sahara, N., Skipper, L., Yager, D., Eckman, C., Hardy, J., Hutton, M., McGowan, E.: Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science (New York, N.Y.). 293(5534), 1487 (2001)

Umeda, T., Maekawa, S., Kimura, T., Takashima, A., Tomiyama, T., Mori, H.: Neurofibrillary tangle formation by introducing wild-type human tau into APP transgenic mice. Acta Neuropathol. 127(5), 685–698 (2014)

Haass, C., Schlossmacher, M.G., Hung, A.Y., Vigo-Pelfrey, C., Mellon, A., Ostaszewski, B.L., Lieberburg, I., Koo, E.H., Schenk, D., Teplow, D.B., Selkoe, D.J.: Amyloid β-peptide is produced by cultured cells during normal metabolism. Nature. 359, 322 (1992)

Takami, M., Nagashima, Y., Sano, Y., Ishihara, S., Morishima-Kawashima, M., Funamoto, S., Ihara, Y.: γ-Secretase: successive tripeptide and tetrapeptide release from the transmembrane domain of β-carboxyl terminal fragment. J. Neurosci. 29(41), 13042 (2009)

Jakob-Roetne, R., Jacobsen, H.: Alzheimer’s disease: from pathology to therapeutic approaches. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48(17), 3030–3059 (2009)

Dahlgren, K.N., Manelli, A.M., Stine, W.B., Baker, L.K., Krafft, G.A., LaDu, M.J.: Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-β peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J. Biol. Chem. 277(35), 32046–32053 (2002)

Lesné, S., Koh, M.T., Kotilinek, L., Kayed, R., Glabe, C.G., Yang, A., Gallagher, M., Ashe, K.H.: A specific amyloid-β protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 440, 352 (2006)

Cheng, I.H., Scearce-Levie, K., Legleiter, J., Palop, J.J., Gerstein, H., Bien-Ly, N., Puoliväli, J., Lesné, S., Ashe, K.H., Muchowski, P.J., Mucke, L.: Accelerating amyloid-β fibrillization reduces oligomer levels and functional deficits in Alzheimer disease mouse models. J. Biol. Chem. 282(33), 23818–23828 (2007)

Mann, D.M., Iwatsubo, T., Ihara, Y., Cairns, N.J., Lantos, P.L., Bogdanovic, N., Lannfelt, L., Winblad, B., Maat-Schieman, M.L., Rossor, M.N.: Predominant deposition of amyloid-β42(43) in plaques in cases of Alzheimer’s disease and hereditary cerebral hemorrhage associated with mutations in the amyloid precursor protein gene. Am. J. Pathol. 148(4), 1257–1266 (1996)

Billings, L.M., Oddo, S., Green, K.N., McGaugh, J.L., LaFerla, F.M.: Intraneuronal Aβ causes the onset of early Alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive deficits in transgenic mice. Neuron. 45(5), 675–688 (2005)

Jin, S., Kedia, N., Illes-Toth, E., Haralampiev, I., Prisner, S., Herrmann, A., Wanker, E.E., Bieschke, J.: Amyloid-β(1–42) aggregation initiates its cellular uptake and cytotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 291(37), 19590–19606 (2016)

Dodart, J.-C., Bales, K.R., Gannon, K.S., Greene, S.J., DeMattos, R.B., Mathis, C., DeLong, C.A., Wu, S., Wu, X., Holtzman, D.M., Paul, S.M.: Immunization reverses memory deficits without reducing brain Aβ burden in Alzheimer’s disease model. Nat. Neurosci. 5, 452 (2002)

Gandy, S., Simon, A.J., Steele, J.W., Lublin, A.L., Lah, J.J., Walker, L.C., Levey, A.I., Krafft, G.A., Levy, E., Checler, F., Glabe, C., Bilker, W.B., Abel, T., Schmeidler, J., Ehrlich, M.E.: Days to criterion as an indicator of toxicity associated with human Alzheimer amyloid-β oligomers. Ann. Neurol. 68(2), 220–230 (2010)

Erten-Lyons, D., Woltjer, R.L., Dodge, H., Nixon, R., Vorobik, R., Calvert, J.F., Leahy, M., Montine, T., Kaye, J.: Factors associated with resistance to dementia despite high Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 72(4), 354 (2009)

Lesné, S.E., Sherman, M.A., Grant, M., Kuskowski, M., Schneider, J.A., Bennett, D.A., Ashe, K.H.: Brain amyloid-β oligomers in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 136(5), 1383–1398 (2013)

Sakono, M., Zako, T.: Amyloid oligomers: formation and toxicity of Aβ oligomers. FEBS J. 277(6), 1348–1358 (2010)

Bernstein, S.L., Dupuis, N.F., Lazo, N.D., Wyttenbach, T., Condron, M.M., Bitan, G., Teplow, D.B., Shea, J.-E., Ruotolo, B.T., Robinson, C.V., Bowers, M.T.: Amyloid-β protein oligomerization and the importance of tetramers and dodecamers in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Chem. 1, 326 (2009)

Bernstein, S.L., Wyttenbach, T., Baumketner, A., Shea, J.-E., Bitan, G., Teplow, D.B., Bowers, M.T.: Amyloid β-protein: monomer structure and early aggregation states of Aβ42 and its Pro19 alloform. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127(7), 2075–2084 (2005)

Economou, N.J., Giammona, M.J., Do, T.D., Zheng, X., Teplow, D.B., Buratto, S.K., Bowers, M.T.: Amyloid β-protein assembly and Alzheimer’s disease: dodecamers of Aβ42, but not of Aβ40, seed fibril formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138(6), 1772–1775 (2016)

Leissring, M.A., Murphy, M.P., Mead, T.R., Akbari, Y., Sugarman, M.C., Jannatipour, M., Anliker, B., Müller, U., Saftig, P., De Strooper, B., Wolfe, M.S., Golde, T.E., LaFerla, F.M.: A physiologic signaling role for the γ-secretase-derived intracellular fragment of APP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99(7), 4697 (2002)

Wong, G.T., Manfra, D., Poulet, F.M., Zhang, Q., Josien, H., Bara, T., Engstrom, L., Pinzon-Ortiz, M., Fine, J.S., Lee, H.-J.J., Zhang, L., Higgins, G.A., Parker, E.M.: Chronic treatment with the γ-secretase inhibitor LY-411,575 inhibits β-amyloid peptide production and alters lymphopoiesis and intestinal cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 279(13), 12876–12882 (2004)

Milano, J., McKay, J., Dagenais, C., Foster-Brown, L., Pognan, F., Gadient, R., Jacobs, R.T., Zacco, A., Greenberg, B., Ciaccio, P.J.: Modulation of notch processing by γ-secretase inhibitors causes intestinal goblet cell metaplasia and induction of genes known to specify gut secretory lineage differentiation. Toxicol. Sci. 82(1), 341–358 (2004)

Ghosh, A.K., Osswald, H.L.: BACE1 (β-secretase) inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43(19), 6765–6813 (2014)

Wilcock, D.M., Rojiani, A., Rosenthal, A., Subbarao, S., Freeman, M.J., Gordon, M.N., Morgan, D.: Passive immunotherapy against Aβ in aged APP-transgenic mice reverses cognitive deficits and depletes parenchymal amyloid deposits in spite of increased vascular amyloid and microhemorrhage. J. Neuroinflammation. 1, 24–24 (2004)

Pfeifer, M., Boncristiano, S., Bondolfi, L., Stalder, A., Deller, T., Staufenbiel, M., Mathews, P.M., Jucker, M.: Cerebral hemorrhage after passive anti-Aβ immunotherapy. Science (New York, N.Y.). 298(5597), 1379 (2002)

Ferrer, I., Rovira, M.B., Guerra, M.L.S., Rey, M.J., Costa-Jussá, F.: Neuropathology and pathogenesis of encephalitis following amyloid β immunization in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 14, 11–20 (2004)

Gilman, S., Koller, M., Black, R.S., Jenkins, L., Griffith, S.G., Fox, N.C., Eisner, L., Kirby, L., Rovira, M.B., Forette, F., Orgogozo, J.M.: Clinical effects of Aβ immunization (AN1792) in patients with AD in an interrupted trial. Neurology. 64(9), 1553 (2005)

Puzzo, D., Privitera, L., Leznik, E., Fà, M., Staniszewski, A., Palmeri, A., Arancio, O.: Picomolar amyloid-β positively modulates synaptic plasticity and memory in hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 28(53), 14537 (2008)

Giuffrida, M.L., Caraci, F., Pignataro, B., Cataldo, S., De Bona, P., Bruno, V., Molinaro, G., Pappalardo, G., Messina, A., Palmigiano, A., Garozzo, D., Nicoletti, F., Rizzarelli, E., Copani, A.: β-Amyloid monomers are neuroprotective. J. Neurosci. 29(34), 10582 (2009)

Zou, K., Gong, J.-S., Yanagisawa, K., Michikawa, M.: A novel function of monomeric amyloid β-protein serving as an antioxidant molecule against metal-induced oxidative damage. J. Neurosci. 22(12), 4833 (2002)

Kim, J., Onstead, L., Randle, S., Price, R., Smithson, L., Zwizinski, C., Dickson, D.W., Golde, T., McGowan, E.: Aβ40 inhibits amyloid deposition in vivo. J. Neurosci. 27(3), 627–633 (2007)

Härd, T., Lendel, C.: Inhibition of amyloid formation. J. Mol. Biol. 421(4), 441–465 (2012)

Scherzer-Attali, R., Farfara, D., Cooper, I., Levin, A., Ben-Romano, T., Trudler, D., Vientrov, M., Shaltiel-Karyo, R., Shalev, D.E., Segev-Amzaleg, N., Gazit, E., Segal, D., Frenkel, D.: Naphthoquinone-tyrptophan reduces neurotoxic Aβ*56 levels and improves cognition in Alzheimer’s disease animal model. Neurobiol. Dis. 46(3), 663–672 (2012)

Ryan, T.M., Roberts, B.R., McColl, G., Hare, D.J., Doble, P.A., Li, Q.-X., Lind, M., Roberts, A.M., Mertens, H.D.T., Kirby, N., Pham, C.L.L., Hinds, M.G., Adlard, P.A., Barnham, K.J., Curtain, C.C., Masters, C.L.: Stabilization of nontoxic Aβ-oligomers: insights into the mechanism of action of hydroxyquinolines in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 35(7), 2871 (2015)

Zheng, X., Liu, D., Klärner, F.-G., Schrader, T., Bitan, G., Bowers, M.T.: Amyloid β-protein assembly: the effect of molecular tweezers CLR01 and CLR03. J. Phys. Chem. B. 119(14), 4831–4841 (2015)

Lee, S., Zheng, X., Krishnamoorthy, J., Savelieff, M.G., Park, H.M., Brender, J.R., Kim, J.H., Derrick, J.S., Kochi, A., Lee, H.J., Kim, C., Ramamoorthy, A., Bowers, M.T., Lim, M.H.: Rational design of a structural framework with potential use to develop chemical reagents that target and modulate multiple facets of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136(1), 299–310 (2014)

Zheng, X., Gessel, M.M., Wisniewski, M.L., Viswanathan, K., Wright, D.L., Bahr, B.A., Bowers, M.T.: Z-Phe-ala-diazomethylketone (PADK) disrupts and remodels early oligomer states of the Alzheimer disease Aβ42 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 287(9), 6084–6088 (2012)

LeVine, H., Ding, Q., Walker, J.A., Voss, R.S., Augelli-Szafran, C.E.: Clioquinol and other hydroxyquinoline derivatives inhibit Aβ(1–42) oligomer assembly. Neurosci. Lett. 465(1), 99–103 (2009)

Rammes, G., Gravius, A., Ruitenberg, M., Wegener, N., Chambon, C., Sroka-Saidi, K., Jeggo, R., Staniaszek, L., Spanswick, D., O'Hare, E., Palmer, P., Kim, E.-M., Bywalez, W., Egger, V., Parsons, C.G.: MRZ-99030—a novel modulator of Aβ aggregation: II—reversal of Aβ oligomer-induced deficits in long-term potentiation (LTP) and cognitive performance in rats and mice. Neuropharmacology. 92, 170–182 (2015)

Arai, T., Sasaki, D., Araya, T., Sato, T., Sohma, Y., Kanai, M.: A cyclic KLVFF-derived peptide aggregation inhibitor induces the formation of less-toxic off-pathway amyloid-β oligomers. Chembiochem. 15(17), 2577–2583 (2014)

Hayden, E.Y., Yamin, G., Beroukhim, S., Chen, B., Kibalchenko, M., Jiang, L., Ho, L., Wang, J., Pasinetti, G.M., Teplow, D.B.: Inhibiting amyloid β-protein assembly: size–activity relationships among grape seed-derived polyphenols. J. Neurochem. 135(2), 416–430 (2015)

Taylor, M., Moore, S., Mayes, J., Parkin, E., Beeg, M., Canovi, M., Gobbi, M., Mann, D.M.A., Allsop, D.: Development of a proteolytically stable retro-inverso peptide inhibitor of β-amyloid oligomerization as a potential novel treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemistry. 49(15), 3261–3272 (2010)

Yamin, G., Ruchala, P., Teplow, D.B.: A peptide hairpin inhibitor of amyloid β-protein oligomerization and fibrillogenesis. Biochemistry. 48(48), 11329–11331 (2009)

Yang, F., Lim, G.P., Begum, A.N., Ubeda, O.J., Simmons, M.R., Ambegaokar, S.S., Chen, P.P., Kayed, R., Glabe, C.G., Frautschy, S.A., Cole, G.M.: Curcumin inhibits formation of amyloid β oligomers and fibrils, binds plaques, and reduces amyloid in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 280(7), 5892–5901 (2005)

Ranu, S., Singh, A.K.: Novel method for pharmacophore analysis by examining the joint pharmacophore space. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 51(5), 1106–1121 (2011)

Lang, C.A., Ray, S.S., Liu, M., Singh, A.K., Cuny, G.D.: Discovery of LRRK2 inhibitors using sequential in silico joint pharmacophore space (JPS) and ensemble docking. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 25(13), 2713–2719 (2015)

Lomakin, A., Chung, D.S., Benedek, G.B., Kirschner, D.A., Teplow, D.B.: On the nucleation and growth of amyloid beta-protein fibrils: detection of nuclei and quantitation of rate constants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93(3), 1125–1129 (1996)

Wyttenbach, T., Kemper, P.R., Bowers, M.T.: Design of a new electrospray ion mobility mass spectrometer. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 212(1), 13–23 (2001)

Mason, E.A., McDaniel, E.W.: Transport Properties of Ions in Gases. Wiley, New York (1988)

Irwin, J.J., Shoichet, B.K.: ZINC—a free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 45(1), 177–182 (2005)

Izzo, N.J., Staniszewski, A., To, L., Fa, M., Teich, A.F., Saeed, F., Wostein, H., Walko 3rd, T., Vaswani, A., Wardius, M., Syed, Z., Ravenscroft, J., Mozzoni, K., Silky, C., Rehak, C., Yurko, R., Finn, P., Look, G., Rishton, G., Safferstein, H., Miller, M., Johanson, C., Stopa, E., Windisch, M., Hutter-Paier, B., Shamloo, M., Arancio, O., LeVine 3rd, H., Catalano, S.M.: Alzheimer’s therapeutics targeting amyloid beta 1-42 oligomers I: Abeta 42 oligomer binding to specific neuronal receptors is displaced by drug candidates that improve cognitive deficits. PLoS One. 9(11), e111898 (2014)

Izzo, N.J., Xu, J., Zeng, C., Kirk, M.J., Mozzoni, K., Silky, C., Rehak, C., Yurko, R., Look, G., Rishton, G., Safferstein, H., Cruchaga, C., Goate, A., Cahill, M.A., Arancio, O., Mach, R.H., Craven, R., Head, E., LeVine 3rd, H., Spires-Jones, T.L., Catalano, S.M.: Alzheimer’s therapeutics targeting amyloid beta 1-42 oligomers II: Sigma-2/PGRMC1 receptors mediate Abeta 42 oligomer binding and synaptotoxicity. PLoS One. 9(11), e111899 (2014)

Zheng, X., Wu, C., Liu, D., Li, H., Bitan, G., Shea, J.-E., Bowers, M.T.: Mechanism of C-terminal fragments of amyloid β-protein as Aβ inhibitors: do C-terminal interactions play a key role in their inhibitory activity? J. Phys. Chem. B. 120(8), 1615–1623 (2016)

de Almeida, N.E.C., Do, T.D., LaPointe, N.E., Tro, M., Feinstein, S.C., Shea, J.E., Bowers, M.T.: 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-galloyl-β-D-glucopyranose binds to the N-terminal metal binding region to inhibit amyloid β-protein oligomer and fibril formation. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 420, 24–34 (2017)

Mastrangelo, I.A., Ahmed, M., Sato, T., Liu, W., Wang, C., Hough, P., Smith, S.O.: High-resolution atomic force microscopy of soluble Aβ42 oligomers. J. Mol. Biol. 358(1), 106–119 (2006)

Kim, J.M., Jung, H.S., Park, J.W., Lee, H.Y., Kawai, T.: AFM phase lag mapping for protein–DNA oligonucleotide complexes. Anal. Chim. Acta. 525(2), 151–157 (2004)

Round, A.N., Miles, M.J.: Exploring the consequences of attractive and repulsive interaction regimes in tapping mode atomic force microscopy of DNA. Nanotechnology. 15(4), S176 (2004)

García, R., Magerle, R., Perez, R.: Nanoscale compositional mapping with gentle forces. Nat. Mater. 6, 405 (2007)

Gazit, E.: A possible role for π-stacking in the self-assembly of amyloid fibrils. FASEB J. 16(1), 77–83 (2002)

Marshall, K.E., Morris, K.L., Charlton, D., O’Reilly, N., Lewis, L., Walden, H., Serpell, L.C.: Hydrophobic, aromatic, and electrostatic interactions play a central role in amyloid fibril formation and stability. Biochemistry. 50(12), 2061–2071 (2011)

Bleiholder, C., Do, T.D., Wu, C., Economou, N.J., Bernstein, S.S., Buratto, S.K., Shea, J.-E., Bowers, M.T.: Ion mobility spectrometry reveals the mechanism of amyloid formation of Aβ(25–35) and its modulation by inhibitors at the molecular level: epigallocatechin gallate and scyllo-inositol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135(45), 16926–16937 (2013)

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institute of Health – National Institute of Aging under grant 1R01AG047116 (M.T.B.) and funding through MURI and DURIP programs of the U.S. Army Research Office under Grant Nos. DAAD 19-03-1-0121 and W911NF-09-1-0280 for the purchase of the AFM instrument (S.K.B.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(PDF 600 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Downey, M.A., Giammona, M.J., Lang, C.A. et al. Inhibiting and Remodeling Toxic Amyloid-Beta Oligomer Formation Using a Computationally Designed Drug Molecule That Targets Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 30, 85–93 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-018-1975-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-018-1975-1