Abstract

The D-residues are crucial to biological function of D-amino acid containing peptides (DAACPs). Previous ion mobility mass spectrometry (IM-MS) studies revealing oligomerization patterns of amyloid cascade demonstrated conversion from native soluble unstructured assembly to fibril ß-sheet oligomers, which has been implicated in amyloid diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes. Although neuropeptides are typically present at very low concentrations in circulation, their local concentrations could be much higher in large dense core vesicles, forming dimers or oligomers. We studied the oligomerization of protonated and metal-adducted achatin I and dermorphin peptide isomers with IM-MS. Our results suggested that dimerization, oligomerization, and metal adduction augment the structural differences between D/L peptide isomers compared to protonated monomers. Dimers and oligomers enhanced the structural differences between D/L peptide isomers in both aqueous and organic solvent system. Furthermore, some oligomer forms were only observed for either D- or L-isomers, indicating the importance of chiral center in oligomerization process. The oligomerization patterns of D/L isomers appear to be similar. Potassium adducts were detected to enlarge the structural differences between D/L isomers.

ᅟ

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

D-amino acid containing peptides (DAACPs) are diastereomers with significant biological functions. Every amino acid (except glycine) can occur in two isomeric forms because of their ability to form stereoisomers around the central α-carbon atom. The DAACP and its corresponding L-form isomer constitute peptide epimers. Before the first DAACP, dermorphin, was isolated in 1981 [1], it was believed that all proteins and peptides were comprised of only L-amino acids. To date, more than 30 endogenous DAACPs have been found in living organisms [2], including crustaceans [3, 4], snails [5–7], spiders [8], frogs [9–11], and even mammals [12, 13]. For example, the spider-venom agatoxins [14], a crustacean hormone [15], and sheep crystallin proteins [16], all contain DAACPs. The D-amino acid residues produced by post-translational isomerization have been proven to be crucial to the biological activities of DAACPs. For example, the DAACP cardioactive peptide (NdWFamide) significantly enhances the beating amplitude of an Aplysia heart at nM level, whereas the L-isomer has little effect even at μM level [7, 17]. Achatin I, which contains D-phenylalanine, can excite muscles of the snail, but its L-isomer does not have this function [5]. These observations and reports raise a series of intriguing questions. For example, why are the activities of D/L isomers so different? How much do D/L isomers differ in conformation? Which factors may enhance the differences of these isomers? The first step towards answering these intriguing questions is to develop methods that characterize these structural isomers.

D/L isomer separation is challenging for mass spectrometry (MS) as the isomerization does not change the elemental composition, molecular formula, or mass of the peptide. However, the gas-phase basicities of the diastereomers can be differentiated when they break apart into fragments [18] and thus can be manifested as different branching ratios among product ions [19]. As a result, MS has become a powerful tool to study DAACPs [20–22]. Fragmentation patterns generated during MS/MS sequencing were used to probe the thermochemical difference between peptide diastereomers during collision-induced dissociation (CID) [20], electron capture dissociation [21], or radical-directed dissociation (RDD) [22]. Although excellent differentiation and quantitation between D/L peptide isomers can be accomplished by these strategies, localization of D-amino acid in peptides is still difficult, as measurement of fragment ion intensities cannot provide accurate positional information of D-amino acids. Our previous study introduced a novel ion mobility mass spectrometry (IM-MS) based strategy enabling site-specific characterization of DAACP isomers to localize D-amino acids [23].

The folding of peptide monomers and oligomers, including conformational changes and oligomerization patterns, have been investigated by IM-MS [24–27]. In neurodegenerative diseases, amyloid cascades transform the native unstructured peptide into ß-sheet oligomers forming insoluble plaques [28–30]. The Bowers group studied this conformational conversion with IM-MS. Their study revealed that the unstructured soluble peptide assemblies and insoluble amyloid plaque followed different oligomerization patterns, as shown by different distribution trends of collision cross-section as a function of aggregation state [24]. Although neuropeptides and neurotransmitters are typically present at very low concentrations throughout the nervous system, their concentrations could be much higher in neuronal organelle. For example, the concentration of a neuropeptide in a large dense-core vesicle is 3–10 mM [31], the concentration of acetylcholine (ACh) in synaptic vesicles is ~260 mM [32], the vesicular concentration of catecholamine in chromaffin cells is 190–300 mM [33], and that of dopamine in midbrain neurons is ~300 mM [34]. This paradox prompted an interesting question whether concentrated DAACPs could also form oligomers and, if so, what kind of biomedical consequences the DAACP oligomerization might have. Elucidating the oligomerization pattern and structural changes is important for understanding the activities of DAACPs. Therefore, we set out to study the conformational differences of monomer, dimers, and oligomers, using T-Wave IM-MS.

Peptide oligomers that form different assemblies in solution have been characterized [35–37]. The growth of the oligomers was monitored with IM-MS by measuring collision cross-section (CCS). The correlation function between CCS (Y) and oligomer size (n) is different depending on the assembly types [24]. For example, in spatially isotropic self-assembly, the relation is Y = Ymon * n2/3, where Ymon is the monomer CCS; whereas in fibrillary self-assembly, Y = a * n + k, where a and k are constants. Thus, the types of self-assembly could be distinguished via the correlation function between CCS and oligomer size, referred to as oligomerization pattern hereafter. In this study, we investigated the oligomerization patterns and conformational changes induced by metal binding and other factors. According to our study, dimerization, oligomerization, and metal adduct formation augment the structural differences of D/L peptide isomers and thus improving the separation and resolution of these important epimers in IM-MS.

Methods

Chemicals and Biological Samples

Methanol was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Optima grade water, acetonitrile (ACN), acetic acid (HAc), and ammonium acetate (certified ACS) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Peptide standards were purchased from American Peptide Company. [D-Ala]-dermorphin (Y(D/L)AFGYPS), [D-Phe]-achatin-I (G(D/L)FAD), and their all-L forms were synthesized in Biotechnology Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

CCS Calibration and Measurement

The CCS calibration strategy is similar to that described by Bush et al. [38], but we used a drift-time/CCS power relationship instead of a quadratic relationship [39]. Since T-Wave IM-MS utilizes non-uniform, dynamic electric field to push ions through a buffer gas [40], the Mason-Schamp equation was empirically modified as Equation 1. The variable Ω is the CCS, z is the ion charge state, e is the fundamental charge, Kb is Boltzmann’s constant, T is temperature, m is the mass of the analyte, M is the mass of the drift gas, P is the pressure, N is the buffer gas number density, and tD is the ion’s drift time or arrival time. The constants A and B result from the non-uniformity of the electric field and must be determined by calibration. The CCS can be normalized by reduced mass and charge state (Ω′), and all other variables can be collapsed into a single term (A′) in Equation 2. A′ and B will be determined by using polyalanine as calibration standard.

Polyalanine was suspended in 50% ACN, 1% HAc at 0.1 mg mL–1, and acquired under six different T-Wave IM wave velocity (WV)/wave height (WH) ratios (m s–1 V–1): 500/30, 500/35, 600/35, 600/40, 700/35, and 800/40. WH refers to the magnitude of the sequential voltage pulses that make up the traveling wave, and WV refers to the propagation speed of those pulses. Instrument parameters were optimized to minimize ion heating during transmission. These parameters include the spray voltage (nano ESI capillary voltage), cone voltage, extraction cone voltage (orthogonal skimmer cone), trap bias (energy for injection into helium cell), and helium cell DC (energy for injection into IM cell) set to 2.0 kV, 30 V, 4 V, 35 V, and 15 V, respectively. The source temperature was set to 70 oC. Data processing was conducted using MassLynx 4.1 and DriftScope 2.1. The measured drift time profiles were calibrated into absolute CCS with a home-built software package.

Direct Infusion

IM-MS was performed with the nanospray source of the Synapt G2 HDMS (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) in positive ionization mode with nitrogen as IM-MS buffer gas. The average pressures (mbar) of the instrument backing, source, trap, and helium cell were 2.73, 1.22 × 10–3, 2.66 × 10–2, and 1.46 × 103, respectively. For experiments conducted with aqueous buffer, analytes were dissolved in 500 mM ammonium acetate buffer at concentrations of 1 mg/ml (~1.3 mM). For experiments conducted in organic solvent, analytes were dissolved in 50:50 water/methanol solution, and sample concentration was 1 mg/ml (~1.3 mM). The samples were directly infused into a Synapt G2 HDMS mass spectrometer equipped with a nano-ESI ion source at a rate of 0.05 μL/min. The ion of interest was isolated by the quadrupole. The CCS distributions were converted from extracted drift time distributions with a window of 0.001 Th.

Results and Discussion

Dimerization Enhances Structural Difference in Both Aqueous and 50% Methanol/water Solvents

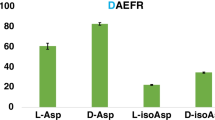

For the D/L peptide pairs we studied, dimers presented larger conformational difference compared to monomers. The drift time for monomer and dimer of achatin I and dermorphin isomers were recorded in IM-MS under six different WH/WV settings. To obtain decent IM-MS signals, we acquired data for 30–60 min for each set. Owing to a limited sample amount, the IM-MS profile of achatin I in aqueous condition was not recorded; the data was only acquired in 50% methanol/water. The profiles of dermorphin were recorded in both solvents. In both aqueous and 50% methanol/water solution, the monomers of those pairs did not differ much in mobility, but dimers exhibited much greater differences (Figure 1). We further converted the drift time into collision cross-section using polyalanine as standard calibrant. The relative CCS difference, which is the CCS difference between D-form and L-form divided by CCS of L-form, was calculated. In organic solvent, the difference increased from 0.57% for the achatin I monomer to 2.91% for the achatin I dimer. For dermorphin, the difference was null for the monomer in both aqueous and 50% methanol/water solvents, and increased to 1.2% and 1.1% for the dimer, respectively.

Dimerization enhanced structural differences of peptide isomers. (a) Achatin I (G(D/L)FAD, MW 408.41 Da) in 50% methanol/water, the relative CCS difference increased from 0.57% for the monomer to 2.91% for the dimer. (b) Dermorphin (Y(D/L)AFGYPS, MW 802.89 Da) in 50% methanol/water, the relative CCS difference increased from null for the monomer to 1.2% for the dimer. (c) Dermorphin in aqueous solution, the relative CCS difference increased from null for the monomer to 1.1% for the dimer

Although the structures of diastereomers are very different around the chiral center and in most cases could be easily separated by chiral or even normal reversed-phase HPLC, the chirality did not much affect the collision cross-section or the mobility of the molecules as was measured in IM-MS. The reason might be for short peptides (e.g., 4–7 amino acid peptide), their secondary structures were not significantly affected by isomerization, especially when measured in the gas phase. The relatively low resolution of IM-MS, or T-Wave IM-MS more specifically, could further contribute to the small differences observed. IM-MS separates gas-phase ions based on their differential mobility through a buffer gas. IM-MS gains advantages on rapid separation speed (on the millisecond timescale versus HPLC typically on the scale of seconds), and low detection limit (attomole amounts, which is a 10-fold improvement compared with HPLC) [41]. However, T-Wave IM-MS does suffer from low resolving power (R < 100 Ω/ΔΩ), meaning that an ion with Ω of 1000 Å2 can theoretically be well separated from an ion with ±10 Å2 difference in Ω [41]. As a result, although the local conformation around the chiral center of the DAACP monomers differs largely, the conformational difference we observed in IM-MS could be quite small. A benchmark study performed by the Ruotolo’s group showed the relative standard deviation values in CCS, as a function of Weight Height, for alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) tetramers demonstrating a small amount of variation, ranging from 0.1% to 0.3% [42]. The relative CCS differences of the dimers observed in our study, being 1% to 2.9%, were 10 to 30 times larger than the typical systematic variation, suggesting that the conformational differences between the D/L dimers measured in IM-MS study are rather significant. Although the measured peptides may have different conformations in organic or native solution, the overall trend in both native (aqueous) and denatured conditions suggested that dimerization enhanced conformational differences between D/L peptide isomers.

Oligomers Were Detected for Dermorphin Isomers in Aqueous and 50% Methanol/water Solvents with Unique Conformers to D- or L-isomers Being Observed

Our IM-MS data suggested that peptide oligomerization was observed for D/L dermorphin in both aqueous and 50% methanol/water solvents. We tested our hypothesis that D/L dermorphin can form oligomers at 1 mg/mL (~1.3 mM) in aqueous and 50% methanol/water solvents. High order oligomers were detected in both D- and L-forms and in both solvents. We annotated each ion with its number of subunits and charge state, shown in Figure 2. Fewer number of different oligomer peaks were detected in aqueous solution compared with 50% methanol/water solvent, whereas more salt adducts were detected in aqueous solution. The reason could be that the ionization efficiency of the peptide oligomers in aqueous samples was poor and thus not all the oligomers were observed in IM-MS or much more nonspecific binding occurred in organic solvent and, thus. more oligomers were observed.

Oligomers of either D- or L-form assume certain conformations that were absent from the other form, indicating the importance of chiral center for oligomerization. As is shown in the representative IM-MS drift time distributions of dermorphin oligomers (Figure 3), many D/L dermorphin oligomers share similar conformations while different conformations are also present in oligomers, such as decamer at +4 charge state and docosamer at +6 charge state. We also studied the dynamic conversion of oligomer conformation by adjusting the ratio of D/L isomers among 100% D-dermorphin, 50%/50% D- and L-dermorphin, and 100% L-dermorphin. As shown in Figure 4, all conformers, which were unique to D- or L-isomers, were present in the 50/50 mixture. For example, for the 10/4 oligomer a larger percentage of the molecules existed as the more extended form in pure D form, whereas in pure L form the majority adopted the more compact conformation, and the 50/50 mixture contained both conformations.

Oligomerization Pattern

Collision cross-section (CCS) reflects the size and shape differences of different ions, and correlation between CCS and number of subunit in the molecules provides information on oligomerization type of the oligomers. We measured the mobility of D/L dermorphin at six different WH/WV settings and converted the drift time to absolute CCS using polyalanine as calibration standard. The average CCS under six settings was reported as the representative CCS value of the dermorphin oligomers. The oligomerization pattern was determined by calculating the CCS distribution versus the number of oligomer subunits. The oligomerization patterns of D/L dermorphin are likely to be similar in 50% methanol/water (Figure 5a). The distribution could be fitted into an exponential function with the form of Y = A * n ^B, where Y is the CCS value, n represents the number of subunits, and A and B are constants. The fitted equation for D-dermorphin is Y = 212.66 * n0.6311, whereas the equation for L-dermorphin is Y = 216.07 * n0.6193. Since constants A and B are close in both D/L forms, we assume that the oligomerization patterns of D/L dermorphin are likely to be very similar. Their fitted equations are close to spatially isotropic self-assembly model and it is very likely the D/L dermorphin oligomers undergo isotropic assembly. Although chirality affected oligomer conformations, it did not trigger alternative self-assembly patterns in 50% methanol/water based on the results in the current study.

(a) Oligomerization pattern of dermorphin isomers in 50% methanol/water as shown in the collision cross section versus aggregation state distribution. The oligomerization patterns of D/L dermorphin isomers appear to be similar. (b) The collision cross section difference between L- and D-dermorphin oligomers in 50% methanol/water, calculated as the CCS of L-isomers subtract the ones of the corresponding D-isomers. For monomer and oligomer with seven subunits, there was one single measurement and no error bar was obtained for these two data points

Most of the observed oligomers formed by L-form dermorphin are present in a more extended conformation compared with their D-form counterparts. For all the L-form oligomers, we compared the conformations with those of D-form counterparts by calculating the CCS difference between L- and D-form oligomers under six different sets of wave height/wave velocity measurements. The results were shown in Figure 5b, and the CCS difference was increased from null for the monomer to 1~4 Å2 for different oligomers. L-form oligomers exhibited larger CCS, suggesting that the L-form oligomers have more extended conformation in comparison to the D-forms. It might be very possible that the trend was solvent-specific. For the limited IM-MS oligomer peaks detected in aqueous experiments, the D-forms exhibited slightly more extended conformation compared with L-form oligomers; however, the differences are relatively modest. Overall, our observation supported that the chiral center played an important role in forming oligomers and ion mobility was capable of detecting those small changes.

Other techniques, such as native gel analyses, high-resolution atomic force microscopy, electron microscopy, and molecular structural modeling could be combined with IM-MS to verify peptide oligomerization in vitro. Applying native gel analyses of full-length tau and deletion constructs, the Bowers’ group demonstrated that the N-terminal region produced multiple bands, which was consistent with oligomerization [43]. High resolution atomic force microscopy was used to directly image populations of small oligomers and observe features that can be attributed to oligomers with different number of subunits [44]. By combining electron cryomicroscopy, 3D reconstruction, and integrative structural modeling methods, Schmidt and co-workers determined the molecular architecture of a fibril formed by Aβ(1–42). Their model revealed that the individual layers of the Aβ fibril were formed by peptide dimers with face-to-face packing [45]. To confirm the oligomer formation of DAACPs and their oligomerization pattern in large dense core vesicles, we are going to employ electron microscopy, high resolution atomic force microscopy, and molecular simulations to further validate our hypothesis proposed by the IM-MS study. To date, we have tested several other DAACPs, including G(D/L)FFD and Y(D)RFG, demonstrating potential applicability of the methods to other D/L pairs. Additional DAACP isomers will be investigated to reveal general trends of DAACP oligomerization.

Potassium Adducts of Dermorphin Isomers

For some of the oligomers, potassium adduct was detected to enhance the conformational differences between oligomers formed by D/L dermorphin isomers. Potassium adducts were detected in both aqueous and 50% methanol/water solvents. However, in aqueous solution, most of the adducts dissociated in the drift tube during IM-MS measurements, and we were not able to measure the CCS. For some oligomers, e.g., M + K, 3 M + H + K, L- and D-forms showed obvious difference, whereas for some other forms, e.g., 2 M + H + K and 4 M + H + K, little differences were observed (Figure 6). We further tested the conformational dynamic conversion by changing the ratio of D/L dermorphin among 100% L-form, 50/50 D- and L-forms, and 100% D-form. The 50/50 mixture contained conformations from both D- and L-forms.

The drift time profiles and their dynamic conversion of dermorphin oligomer conformations of potassium adducts in 50% methanol/water. Monomer and trimer adducts showed obvious difference between D- and L-forms, whereas the dimer and tetramer adducts did not. The conformational dynamic conversion studies with the ratio of D/L dermorphin changed among 100% L-form, 50/50 D- and L-forms, and 100% D-form showed that the 50/50 mixture preserved conformations from both D- and L-forms. For 100% D-form dermorphin M + K peak, there were two peaks, indicating the presence of at least two conformations

Conclusions

We studied dimerization, oligomerization, and metalation of the D/L peptide isomers using IM-MS. Dimers, oligomers, and metal adducts were detected in both aqueous and 50% methanol/water solutions. The relative CCS difference of the peptide isomers increased when monomers were converted into dimers, indicating that dimerization enhanced the structural difference of peptide isomers in both aqueous and 50% methanol/water solutions. In both solvent systems, oligomers were detected. The IM-MS results showed some conformers found only for D- or L-isomers, suggesting the importance of chiral center in the oligomerization process. The CCS versus aggregation state distribution of the dermorphin isomers exhibited a similar trend, whereas oligomerization enlarged the CCS difference from null for the monomer to 1~4 Å2 for different oligomers. Potassium adducts augmented the structural differences between D/L isomers, and the dynamic conversion of oligomer conformations showed 50/50 mixture presented unique conformations in either D- or L-forms. In summary, we demonstrate that IM-MS can be utilized to probe the structural differences of D/L peptide isomers at dimer, oligomer, and metalation. These differences may provide helpful molecular clues to address the intriguing question why D/L isomers differ significantly in biological activity. Further biochemical investigation and in-depth characterization of structure–function relationship of DAACPs in monomer and oligomer conditions will be needed to gain a clear mechanistic understanding of the process.

References

Montecucchi, P.C., de Castiglione, R., Piani, S., Gozzini, L., Erspamer, V.: Amino acid composition and sequence of dermorphin, a novel opiate-like peptide from the skin of Phyllomedusa sauvagei. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 17, 275–283 (1981)

Bai, L., Sheeley, S., Sweedler, J.V.: Analysis of endogenous D-amino acid-containing peptides in metazoa. Bioanal. Rev. 1, 7–24 (2009)

Soyez, D., Van Herp, F., Rossier, J., Le Caer, J.P., Tensen, C.P., Lafont, R.: Evidence for a conformational polymorphism of invertebrate neurohormones. D-amino acid residue in crustacean hyperglycemic peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 18295–18298 (1994)

Yasuda, A., Yasuda, Y., Fujita, T., Naya, Y.: Characterization of crustacean hyperglycemic hormone from the crayfish (Procambarus clarkii): multiplicity of molecular forms by stereoinversion and diverse functions. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 95, 387–398 (1994)

Kamatani, Y., Minakata, H., Kenny, P.T., Iwashita, T., Watanabe, K., Funase, K., Sun, X.P., Yongsiri, A., Kim, K.H., Novales-Li, P., Novales, T.N., Lanapi, C.G., Takeuchi, H., Nomoto, K.: Achatin-I, an endogenous neuroexcitatory tetrapeptide from Achatina fulica Ferussac containing a D-amino acid residue. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 160, 1015–1020 (1989)

Yasuda-Kamatani, Y., Kobayashi, M., Yasuda, A., Fujita, T., Minakata, H., Nomoto, K., Nakamura, M., Sakiyama, F.: A novel D-amino acid-containing peptide, fulyal, coexists with fulicin gene-related peptides in Achatina atria. Peptides 18, 347–354 (1997)

Morishita, F., Nakanishi, Y., Kaku, S., Furukawa, Y., Ohta, S., Hirata, T., Ohtani, M., Fujisawa, Y., Muneoka, Y., Matsushima, O.: A novel D-amino-acid-containing peptide isolated from Aplysia heart. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 240, 354–358 (1997)

Heck, S.D., Kelbaugh, P.R., Kelly, M.E., Thadeio, P.F., Saccomano, N.A., Stroh, J.G., Volkmann, R.A.: Disulfide bond assignment of omega-Agatoxin-Ivb and Omega-Agatoxin-Ivc—Discovery of a D-serine residue in omega-Agatoxin-Ivb. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 10426–10436 (1994)

Mor, A., Delfour, A., Sagan, S., Amiche, M., Pradelles, P., Rossier, J., Nicolas, P.: Isolation of dermenkephalin from amphibian skin, a high-affinity delta-selective opioid heptapeptide containing a D-amino acid residue. FEBS Lett. 255, 269–274 (1989)

Kreil, G., Barra, D., Simmaco, M., Erspamer, V., Erspamer, G.F., Negri, L., Severini, C., Corsi, R., Melchiorri, P.: Deltorphin, a novel amphibian skin peptide with high selectivity and affinity for delta opioid receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 162, 123–128 (1989)

Barra, D., Mignogna, G., Simmaco, M., Pucci, P., Severini, C., Falconieri-Erspamer, G., Negri, L., Erspamer, V.: [D-Leu2]deltorphin, a 17 amino acid opioid peptide from the skin of the Brazilian hylid frog, Phyllomedusa burmeisteri. Peptides 15, 199–202 (1994)

Torres, A.M., Menz, I., Alewood, P.F., Bansal, P., Lahnstein, J., Gallagher, C.H., Kuchel, P.W.: D-amino acid residue in the C-type natriuretic peptide from the venom of the mammal, Ornithorhynchus anatinus, the Australian platypus. FEBS Lett. 524, 172–176 (2002)

Torres, A.M., Tsampazi, C., Geraghty, D.P., Bansal, P.S., Alewood, P.F., Kuchel, P.W.: D-amino acid residue in a defensin-like peptide from platypus venom: effect on structure and chromatographic properties. Biochem. J. 391, 215–220 (2005)

Shikata, Y., Watanabe, T., Teramoto, T., Inoue, A., Kawakami, Y., Nishizawa, Y., Katayama, K., Kuwada, M.: Isolation and characterization of a peptide isomerase from funnel web spider venom. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 16719–16723 (1995)

Soyez, D., Vanherp, F., Rossier, J., Lecaer, J.P., Tensen, C.P., Lafont, R.: Evidence for a conformational polymorphism of invertebrate neurohormones—D-amino-acid residue in crustacean hyperglycemic peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 18295–18298 (1994)

Tao, Y., Julian, R.R.: Identification of amino acid epimerization and isomerization in crystallin proteins by tandem LC-MS. Anal. Chem. 86, 9733–9741 (2014)

Sheeley, S.A., Miao, H., Ewing, M.A., Rubakhin, S.S., Sweedler, J.V.: Measuring D-amino acid-containing neuropeptides with capillary electrophoresis. Analyst 130, 1198–1203 (2005)

Cooks, R.G., Wong, P.S.H.: Kinetic method of making thermochemical determinations: Advances and applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 31, 379–386 (1998)

Tao, W.A., Zhang, D.X., Nikolaev, E.N., Cooks, R.G.: Copper(II)-assisted enantiomeric analysis of D,L-amino acids using the kinetic method: chiral recognition and quantification in the gas phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 10598–10609 (2000)

Bai, L., Romanova, E.V., Sweedler, J.V.: Distinguishing endogenous D-amino acid-containing neuropeptides in individual neurons using tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 83, 2794–2800 (2011)

Adams, C.M., Kjeldsen, F., Zubarev, R.A., Budnik, B.A., Haselmann, K.F.: Electron capture dissociation distinguishes a single D-amino acid in a protein and probes the tertiary structure. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 15, 1087–1098 (2004)

Tao, Y., Quebbemann, N.R., Julian, R.R.: Discriminating D-amino acid-containing peptide epimers by radical-directed dissociation mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 84, 6814–6820 (2012)

Jia, C., Lietz, C.B., Yu, Q., Li, L.: Site-specific characterization of D-amino acid-containing peptide epimers by ion mobility spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 86, 2972–2981 (2014)

Bleiholder, C., Dupuis, N.F., Wyttenbach, T., Bowers, M.T.: Ion mobility-mass spectrometry reveals a conformational conversion from random assembly to β-sheet in amyloid fibril formation. Nat. Chem. 3, 172–177 (2011)

Smith, D.P., Radford, S.E., Ashcroft, A.E.: Elongated oligomers in β2-microglobulin amyloid assembly revealed by ion mobility spectrometry-mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 6794–6798 (2010)

Bernstein, S.L., Dupuis, N.F., Lazo, N.D., Wyttenbach, T., Condron, M.M., Bitan, G., Teplow, D.B., Shea, J.E., Ruotolo, B.T., Robinson, C.V., Bowers, M.T.: Amyloid-β protein oligomerization and the importance of tetramers and dodecamers in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Chem. 1, 326–331 (2009)

Wyttenbach, T., Pierson, N.A., Clemmer, D.E., Bowers, M.T.: Ion mobility analysis of molecular dynamics. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 65, 175–196 (2014)

Chiti, F., Dobson, C.M.: Amyloid formation by globular proteins under native conditions. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 15–22 (2009)

Eisenberg, D., Nelson, R., Sawaya, M.R., Balbirnie, M., Sambashivan, S., Ivanova, M.I., Madsen, A.O., Riekel, C.: The structural biology of protein aggregation diseases: fundamental questions and some answers. Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 568–575 (2006)

Haass, C., Selkoe, D.J.: Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid β-peptide. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 101–112 (2007)

Hrdina, P.D., Siegel G.J., Agranoff B.W., Albers R.W., Fisher S.K., Uhler M.D.: Basic neurochemistry: molecular, cellular, and medical aspects, 6th edition. Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia (1999) Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20385/. Accessed 21 June 2016

Kuffler, S.W., Yoshikami, D.: The number of transmitter molecules in a quantum: an estimate from iontophoretic application of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular synapse. J. Physiol. 251, 465–482 (1975)

Wightman, R.M., Jankowski, J.A., Kennedy, R.T., Kawagoe, K.T., Schroeder, T.J., Leszczyszyn, D.J., Near, J.A., Diliberto Jr., E.J., Viveros, O.H.: Temporally resolved catecholamine spikes correspond to single vesicle release from individual chromaffin cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88, 10754–10758 (1991)

Pothos, E.N., Davila, V., Sulzer, D.: Presynaptic recording of quanta from midbrain dopamine neurons and modulation of the quantal size. J. Neurosci. 18, 4106–4118 (1998)

Sawaya, M.R., Sambashivan, S., Nelson, R., Ivanova, M.I., Sievers, S.A., Apostol, M.I., Thompson, M.J., Balbirnie, M., Wiltzius, J.J., McFarlane, H.T., Madsen, A.O., Riekel, C., Eisenberg, D.: Atomic structures of amyloid cross-beta spines reveal varied steric zippers. Nature 447, 453–457 (2007)

Nelson, R., Sawaya, M.R., Balbirnie, M., Madsen, A.O., Riekel, C., Grothe, R., Eisenberg, D.: Structure of the cross-beta spine of amyloid-like fibrils. Nature 435, 773–778 (2005)

Nelson, R., Eisenberg, D.: Recent atomic models of amyloid fibril structure. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 16, 260–265 (2006)

Bush, M.F., Campuzano, I.D., Robinson, C.V.: Ion mobility mass spectrometry of peptide ions: effects of drift gas and calibration strategies. Anal. Chem. 84, 7124–7130 (2012)

Ruotolo, B.T., Benesch, J.L., Sandercock, A.M., Hyung, S.J., Robinson, C.V.: Ion mobility-mass spectrometry analysis of large protein complexes. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1139–1152 (2008)

Shvartsburg, A.A., Smith, R.D.: Fundamentals of traveling wave ion mobility spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 80, 9689–9699 (2008)

Lanucara, F., Holman, S.W., Gray, C.J., Eyers, C.E.: The power of ion mobility-mass spectrometry for structural characterization and the study of conformational dynamics. Nat. Chem. 6, 281–294 (2014)

Zhong, Y., Hyung, S.J., Ruotolo, B.T.: Characterizing the resolution and accuracy of a second-generation traveling-wave ion mobility separator for biomolecular ions. Analyst 136, 3534–3541 (2011)

Feinstein, H.E., Benbow, S.J., LaPointe, N.E., Patel, N., Ramachandran, S., Do, T.D., Gaylord, M.R., Huskey, N.E., Dressler, N., Korff, M., Quon, B., Cantrell, K.L., Bowers, M.T., Lal, R., Feinstein, S.C.: Oligomerization of the microtubule-associated protein tau is mediated by its N-terminal sequences: implications for normal and pathological tau action. J. Neurochem. 137, 939–954 (2016)

Economou, N.J., Giammona, M.J., Do, T.D., Zheng, X., Teplow, D.B., Buratto, S.K., Bowers, M.T.: Amyloid β-protein assembly and Alzheimer's disease: dodecamers of Abeta42, but not of Abeta40, seed fibril formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 1772–1775 (2016)

Schmidt, M., Rohou, A., Lasker, K., Yadav, J.K., Schiene-Fischer, C., Fandrich, M., Grigorieff, N.: Peptide dimer structure in an Abeta(1-42) fibril visualized with cryo-EM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 11858–11863 (2015)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Matthew Glover in the Li Research Group for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions. This work is supported in part by the National Science Foundation grant (CHE-1413596) and the National Institutes of Health grants (1R01DK071801 and 1R56DK071801). L.L. acknowledges a Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professorship with funding provided by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Xueqin Pang and Chenxi Jia contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pang, X., Jia, C., Chen, Z. et al. Structural Characterization of Monomers and Oligomers of D-Amino Acid-Containing Peptides Using T-Wave Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 28, 110–118 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-016-1523-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-016-1523-9