Abstract

Modern geotechnical monitoring is based on a variety of surface-based and integrated sensors. This article discusses the potential but also the limitations of total stations and laser scanners in monitoring of civil infrastructure and natural phenomena. We report about our experiences gained in long-term monitoring projects and discuss the impact of the setup location, the signal travel path, and the target. Although modern instruments are capable of measurements with accuracies of a few millimetres or better, neglecting error sources like temperature dependence of the tilt sensor, orientation of the used prism, obstructions and reflections of the measurement beam, and atmospheric refraction can easily cause errors of several millimetres or even centimetres.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The task of geotechnical engineering is to build structures like tunnels within the ground or to provide solid foundations for structures above the ground. Geotechnical monitoring is used to assess the behaviour of these structures during construction and in the long term. Objects under consideration are manmade structures like tunnels, dams, piles, retaining walls or pipelines, and natural objects like rock faces, slopes, or caves. Geotechnical monitoring is also important for the early warning of natural hazards such as landslides, rock falls, sinkholes, and debris flows. Deformations of the surface of a structure like a landslide can be depicted with a variety of sensors. Current methods are, for instance, airborne and terrestrial laser scanning (ALS and TLS), measurements to prisms with robotic total stations (RTS), GNSS measurements, and ground or satellite-based interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR), see Fig. 1.

The accuracy of contactless measurements with total stations and terrestrial laser scanners always depends on the three components: setup point, measurement path, and measurement target. The setup point includes the instrument itself, the stability of the support, and the objects in the vicinity of the instrument. The measurement path is influenced by the atmospheric conditions which have an impact on the travel speed of the signal. Furthermore, temperature gradients can cause a curvature of the measurement path. The final critical component is the target. The achievable accuracy depends on the target type, e.g., prism or rock, the inclination angle of the measurement path with respect to the target and the target material. In the following, we discuss the possible degradation of the measurement accuracy under different circumstances.

2 Robotic total station measurements

2.1 Impact of the setup point

Modern robotic total stations (RTS) can automatically find and track prism targets. RTS are commonly used for the monitoring during tunnel construction and to assess the stability of water dams, landslides, and rock faces. The instruments are often placed in a measurement chamber (Fig. 2) and thus protected from adverse environmental conditions.

However, the glass window also has an impact on the measurement accuracy. In case of a homogenous glass with parallel faces, the sighting axis is shifted parallel. The amount of this shift depends on the incident angle of the sighting axis φ, the thickness of the glass window d, the refractive index of the glass n glass, and the refractive index of the air n air. The impact of this shift on the horizontal angle measurements Hz can be calculated by

The glass window has also an impact on the distance measurement due to the lower speed of light within glass. The measured distances will, therefore, be too long. The refractive of glass n glass is approximately 1.5, whereas the refractive index of the n air is just slightly above 1. In case of orthogonal measurements through a glass window, the introduced distance error ΔD

is half the thickness of the glass window. This impact increases for inclined measurements because of a longer path distance within glass. This effect can be calculated by

An example of this effect is given in Fig. 3. A very thin glass window (thickness 1.75 mm) was placed in front of the RTS. The instrument measured through this window to a prism. During the experiment, the glass window was slowly turned and thus different incident angles were achieved. The impact on the distance measurements was calculated theoretically (Fig. 3 left) and verified experimentally (Fig. 3 right). It can be seen that already with the very thin glass window distance, deviations of several tenths of a millimetre occur.

In deformation analysis, this impact can often be neglected as deformation measurements always refer to a first measurement epoch and thus constant impacts cancel out. Nevertheless, care has to be taken, in case a window glass is being replaced [1].

What is more critical in deformation measurements are direct reflections from the glass back into the telescope of the instrument. An RTS sends out a laser beam for the distance measurement and illuminates the measurement scenery with infrared light for the automated detection and measurement of targets. The electronic distance measurement (EDM) sensor as well as the targeting sensor are influenced if the signals are not only reflected by the prism but also by the glass window. Therefore, measurements orthogonal to the glass window have to be circumvented. The critical angle in which useful measurements cannot be performed depends on the beam divergence of the transmitted beams, the acceptance angle of the sensors, the distance of the glass window to the instrument, and of course on the angle between glass window and sighting axis. Figure 4 shows examples of measurement situation which should be avoided.

Considering this aspect, it is preferable to avoid glass windows altogether. This is a common approach in inner city monitoring installations. Two different possible solutions are shown in Fig. 5. In Fig. 5 left, the instrument is placed into a metal cage and in Fig. 5 right into a plastic cylinder. Although, no measurements through glass are made, caution is still required. In case of the setup of Fig. 5 left, obstructions due to the bars of the cage have to be avoided. In case of Fig. 5 right, the holes drilled into the cylinder have to have at least the diameter of the telescope objective.

In such a setup, the measurements are not influenced by a glass window, but the instrument experiences all environmental changes. For instance, a temperature change causes a change of the zero point of the internal tilt sensor of the instrument. This tilt sensor is used to automatically correct angle measurement of an unlevelled instrument. Figure 6 right shows the temperature dependence for different instruments. It has to be noted that an error of the tilt reading results in an error of the vertical angle of the same size. As can be seen in Fig. 6, large temperature differences can cause tilt errors of more than 80 cc. This corresponds to a height error of 8 mm of a target which is in 60 m distance. To avoid this error, the zero point of the tilt sensor should be determined in regular intervals. If measurements are made only every few hours, it is recommended to determine the zero point of the tilt sensor at the beginning of every measurement cycle.

The stability of the setup point is also critical in monitoring applications and has to be checked in regular intervals. Possible tilt changes can be detected either using the internal tilt sensor of the RTS (Fig. 7-1), using an external tilt sensor (Fig. 7-2) or by precise levelling of four surveying markers placed into the foundations of a concrete setup pillar (Fig. 7-3). Position changes of the setup point can be detected, for instance using a GNSS sensor at the position of the RTS (Fig. 7-4). To achieve the required accuracy, surveying grade GNSS equipped has to be used and relative GNSS positioning techniques have to be applied. Another approach to verify the stability of the setup position is to perform a resection by measuring directions and distances to at least two stable reference prisms (Fig. 7-5). If the stability of these reference points is not guaranteed, active reference targets can be used. These targets are prisms with a GNSS antenna attached to it (Fig. 7-6). Hence, the current position of this reference target can be determined using GNSS prior to the resection. An example for this approach is also used in the stake out of the formwork of high rise buildings [2].

2.2 Impact of the measurement path

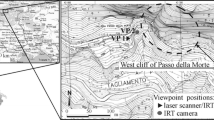

As mentioned before, the setup point is only one essential component. The second component is the measurement path. Geodetic measurements are always made through the atmosphere. Potential problems arising from inhomogeneous atmospheric conditions are discussed in the following using the monitoring of a rock face as example.

The “Biratalwand” is a rock face located next to the Danube in Austria. A public road and a train line are located just beneath the rock face. To provide a warning system, two RTS (Fig. 8) performed automated distance and angle measurements in regular intervals to prims installed in the unstable area of the rock face. Accurate coordinates can only be derived from these measurements if atmospheric effects are taken into account. The travel speed of the emitted light of the EDM unit of the RTS depends on the refractive index of the air which is mainly influenced by the mean air temperature T and the mean pressure p along the measurement path. Relative humidity h also has a noticeable impact [3]. To compensate for these impacts, atmospheric correction factors have to be applied. These are usually given as a scale factor m, and since this scale factor also depends on the laser wavelength, each manufacturer provides individual equations. Furthermore, each manufacturer has set the correction to zero at a specific combination of temperature, pressure, and humidity values. For Leica TS instruments, the correction is zero at T = 12 °C, p = 1013.3 mbar, h = 60% [4], and for Topcon PS instrument, m is zero at T = 15 °C, p = 1013 mbar, h = 50% [5]:

It has to be noted that a deviation from these zero correction situations of 1 °C or 3.6 mbar causes a scale error of 1 × 10−6. Assuming a mean air temperature of 25 °C and using a Leica instrument to measure a distance of 1 km, neglecting the atmospheric impact would result in a distance error of 10 mm which is well above the specified precision of the instrument. Hence, the current atmospheric conditions have to be taken into account. Since it is impossible to measure the temperature distribution along the whole measurement path, usual solutions are the measurement of the atmospheric conditions in the vicinity of the setup point (e.g., using a weather station) or the measurement of the atmospheric conditions at the setup point and the target location. In monitoring applications, the measurement of the atmospheric conditions at the target point is often not possible and thus other approaches like the local scale parameter method (LSPM) [6] have to be applied. In [7], it is shown that with the LSPM, the impact of atmospheric conditions on the distance measurements can be reduced to less than 0.5 mm.

The atmospheric conditions can also have an impact on the angle measurements. It can be seen in Fig. 9 that the vertical angle measurements of a point on the Briatalwand rock face show daily cycles. It is obvious that the rock face does not move down and up again. Therefore, uncorrected systematic effect must be inherent in the measurement data.

A detailed investigation of the measurement data and additional experiments on site revealed that a potential cause of the impact is geodetic refraction which causes beam bending. The impact of refraction on automated angle measurements is shown in Fig. 10. At the start of every measurement epoch cycle, the instrument turns to the stored position of the target point (1). In case of no refraction and no movement of the target, the instrument points directly to the target. However, in case of refraction, the measurement path is curved and thus the instrument incorrectly assumes a movement of the target and turns until the aiming sensor detects the target again (2). When the target is found, the angle reading is stored (3) which is in fact the tangent to the curved measurement path at the instrument position.

To eliminate this impact, it is possible to use a stable target in the vicinity of the moveable area. This stable target can be used as calibration target to calculate the current impact of the refraction and apply numerical corrections to the measurements of the moveable targets. Figure 11 shows the time series of the vertical angle to the target in the unstable area after the correction. It can be seen that the daily cycles are not present anymore and that the rock was, in fact, stable within the displayed 6 days.

2.3 Impact of the target

The final component, which can have an impact on the accuracy of RTS measurements, is the target. Prisms of various sizes and shapes are commonly used targets in automated monitoring installations. Very convenient are the so-called 360° prisms, because measurements to these prisms are possible from every horizontal angle. However, it has to be noted that 360° prisms show systematic error patterns, which significantly degrade the measurement accuracy. In an optimal situation (near orthogonal measurements to a round prism), measurements can be made with an accuracy of a few tenth of a millimetre. Using a different prism or an unfavourable orientation, errors of several millimetres occur.

360° prisms have several facets which cause cyclic errors. Figure 12 shows the results for horizontal angle measurements to a Leica GRZ122 360° and a Leica GPR121 round prism. The prisms were located at a distance of 26 m and automatically turned. The GRZ122 has six facets which can be clearly identified in the error plot. The deviations cover a range of more than 2 mm. More detailed results of these and other prisms can be found in [8]. Measurements to the round prim are much more accurate if the prism is well aligned to the instrument. If this is not the case, the deviations increase rapidly. As a conclusion, 360° prisms cannot be used for measurements with highest accuracy demands and round prisms should be well aligned to the instrument.

3 Laser scanning and reflectorless RTS measurements

Laser scanning, also called light detection and ranging (LiDAR), is based on a rotating laser beam which is mounted on a stable platform like a tripod or a pillar or on a moveable platform like a car, airplane, or UAV. Modern laser scanners are capable of measuring more than 1 million points per second. Such a fast measurement rate results in huge data amounts within a short time. Today laser scanning is a valuable tool for geotechnical monitoring, because, contrary to total station measurements, it is not necessary to mount targets on the object. Figure 13 shows an example of one of our projects where we performed scanning during a slope stability experiment. A point cloud of one measurement epoch is displayed in Fig. 13 left and right indicates the result of a deformation analysis [9].

Scanned point cloud of an earth dam (left) result of deformation analysis (right) [9] (colour figure online)

Nevertheless, it is has to be noted that laser scanning is also affected by refraction. First, the travel speed of the laser beam is dependent on the atmospheric conditions. Second, beam bending does also have an impact as is indicated in Fig. 14. Contrary, to total stations, laser scanners cannot track targets. The horizontal and vertical angles are only steering angles. In case of refraction, the beam at the same steering angle curves and, therefore, a different part of the object is measured. Depending on the shape of the object, this can have a significant impact on the measured distance.

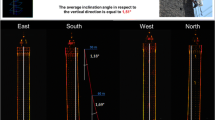

We took a closer look at this impact at the monitoring site Biratalwand. At this location, reflectorless distance measurements showed daily cycles which could not be explained by variations of the signal travel speed. Therefore, dedicated experiments were carried out. In these experiments, the atmospheric conditions were measured in detail, images of the targets were taken with an image-assisted total station, and different measurement schemes were applied [10]. Figure 15 shows an overview and close-up image of an inclined rock face of the Biratalwand. As it was discussed before, the RTS measurements were influenced by daily cycles of the vertical angle within a range of 6 mgon. As can be seen in Fig. 16, such vertical angle variations can result in distance variations of several millimetres due to the inclination of the rock face with respect to the sighting axis.

Influences on the vertical angle can be taken into account according to the aforementioned method using stable reference points in the measurement area. However, it has to be noted that in case of reflectorless distance measurements, the corrections have to be applied already during the steering process of the instrument and not in post-processing as is the case for RTS measurements. We are currently verifying the developed approaches in another case study which focuses on the remote monitoring of retaining walls.

Further factors influencing the laser distance measurements are the target material (absorption characteristic and laser penetration depth), the surface conditions (wet and dry), the surface roughness, and the inclination angle between surface and laser beam.

Currently, we also perform laser scanning measurements at a stalactite cave. In this project, we combine airborne and terrestrial laser scanning. Airborne laser scanning is used to generate the digital surface model above the ground, whereas the cave itself is captured using terrestrial laser scanning, see Figs. 17 and 18.

4 Conclusion

High accurate measurements with total stations and laser scanners require a sound understanding of all potential error sources. In general, the three elements setup point, measurement path, and target have to be considered.

The setup point and its vicinity include the instrument, the stability of the instrument support, and possible protective housings. Measurements through glass windows are not recommended and should only be performed when the sighting axis is not orthogonal to the glass window. The zero point of the instrument’s internal tilt sensor has to be determined in regular intervals and obstructions due to a protective housing have to be avoided. Furthermore, the stability of the setup point has to be verified in regular intervals. Tilt changes can be detected with the internal tilt senor or external sensors. Position changes can be determined with external reference targets and GNSS sensors.

Obstructions along the measurement path have to be avoided and the current refraction status has to be taken into account. Distance corrections can be applied by local atmospheric measurements or using the local scale parameter method. Measurements to stable reference targets in the vicinity of the monitoring object can also be used to mitigate the impact of beam bending.

The used monitoring target, either a prism, reflective foil, or the object surface itself, has a significant impact. The highest accuracy can be achieved when using round prisms and aligning them well to the sighting axis of the instrument. When using the object surface as target, the target material, the surface conditions, the surface roughness, and the inclination angle between surface and laser beam can degrade the achievable accuracy.

References

Frukacz M, Presl R, Wieser A (2016) Pushing the sensitivity limits of TPS-based continuous deformation monitoring of an Alpine Valley, Proc. In: Joint international symposium on deformation monitoring (JISDM), Vienna, Austria

van Cranenbroeck J (2007) Advanced surveying control services for building the vertical cities, Proc. FIG Working Week 2007, Hong Kong, China

Rüeger J (1996) Electronic distance measurement, 4th edn. Springer, New York

Leica Geosystems (2010) Leica TS11/TS15 user manual, v1.0. Leica Geosystems AG, Switzerland

Topcon (2012) Instruction manual power station—PS series. Topcon Corporation, Japan

Brunner FK, Rüeger J (1992) Theory of the local scale parameter method for EDM. Bull Geod 66(1992):355–364

Brunner FK, Lienhart W (2012) Anwendung der Lokalen-Maßstab-Parameter Methode (LSPM) bei der Vermessung einer Kalibrierbasis, avn – Allgemeine Vermessungsnachrichten, 119 (2012):363–368

Lackner S, Lienhart W (2016) Impact of prism type and prism orientation on the accuracy of automated total station measurements, Proc. Joint international symposium on deformation monitoring (JISDM), Vienna, Austria

Lackner S, Lienhart W, Supp G, Marte R (2016) Geodetic and fibre optic measurements of a full-scale bi-axial compressional test. Surv Rev 48(347):86–93

Kleemaier G (2015) Untersuchungen von Fehlereinflüssen bei reflektorlosen Überwachungsmessungen von Felswänden, Master Thesis, Graz University of Technology

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Alexander Trefalt from Vermessung AVT ZT-GmbH for providing data and access to the Biratalwand and Prof. Andreas Wieser from ETH Zurich for the pre-analysis of the Biratalwand data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lienhart, W. Geotechnical monitoring using total stations and laser scanners: critical aspects and solutions. J Civil Struct Health Monit 7, 315–324 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13349-017-0228-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13349-017-0228-5