Abstract

Contemporary ethics is currently ramifying into different sub-ethics specific to each type of technology. Although this trend has been very timely and rightly called into question by Sætra and Danaher, both these authors and their critics Llorca Albareda and Rueda leave the matter unsolved from a discipline point of view. In this commentary, we clarify the statute of the ethics of technology, which corresponds to that of a subsidiary applied ethics, and show how it is precisely that, what renders the creation of an ethics for each technology inappropriate. We thus provide a disciplinary reason to support Sætra and Danaher’s concern on tech ethics proliferation and to refute Llorca Albareda and Rueda’s relativization of it. In turn, we conclude by drawing some guidelines for tech ethics in practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

After the “applied turn” of ethics (Cortina, 2003) and the “empirical turn” of philosophy of technology (Verbeek, 2010) in the 20th century, contemporary ethics seems to have become disoriented in its disciplinary configuration around technology. A symptom of this is the proliferation of tech ethics, that is, the emergence of specific ethics for each type of technologyFootnote 1. But perhaps even more indicative of this disorientation are the discussions that have arisen on this tendency, which prove to share some of the very same disciplinary ambiguities and misunderstandings that gave rise to the current scenario of tech ethics proliferation in the first place and which thereby compromise the validity of the arguments that have so far been provided against or for it. This is the case of Sætra and Danaher (2022), who although rightly calling into question the creation of an ethics for each technology do however overlook what we consider is the most fundamental reason against it, namely: that such proliferation is improper of the statute of the ethics of technology.

Through a laudable critical revision of the main subbranches of the ethics of (computer-based) technology, Sætra and Danaher (2022) aim to prove that tech ethics proliferation is, as a general rule, unnecessary, as well as counterproductive. Unnecessary, since the issues tackled in each of the subdomains of ethical inquiry are rarely new nor exclusive to a certain technological field and can be thus mostly addressed from a genus- and not a species-ethics, i.e., a “high-level” rather than “low-level” ethics (Llorca Albareda & Rueda, 2023). Counterproductive, in that it unduly compartmentalizes ethical reflection, negatively affecting the efficiency and quality of its practical endeavor around technology. By easily fostering monadic and high-ethics uprooted approaches to issues that are not only of common concern to the different tech domains but also related to historical philosophical themes, proliferation dooms ethical inquiry to an inconsistent, repetitive and philosophically shallow work –which, we could add, ends up addressing moral anecdotes rather than ethical problems strictly speaking.

The argumentative inconsistency it implies to prescriptively stand against tech ethics proliferation on the basis of the flaws of the current way of doing it has not gone unnoticed by the first critics Llorca Albareda and Rueda (2023), who do contrarily not condemn the creation of sub-ethics of technology. Still, there is a prior and more essential reason why Sætra and Danaher (2022) response is unsatisfactory, which has to do with a generalized conceptualization of tech ethics as an applied ethics that they uncritically embrace, alongside a poor understanding of the statute and method of this (applied) form of moral philosophy. While Llorca Albareda and Rueda (2023) have rightly tackled the latter shortcoming, they do unfortunately miss the former problem mainly because they do likewise: they misapprehend the statute of the ethics of technology, inasmuch as they share the same wrong presumption of technology as the primary locus of application of ethical reflection. This presumption, that underlies tech ethics proliferation, conflicts with the disciplinary articulation of the ethics of technology, which, as we shall argue, is proper of a subsidiary applied ethics.

By unfolding this, and considering that this is part of what it means to “take ethics seriously” (Sætra & Danaher, 2022, p.2), in this commentary we will justify why we should not create an ethics for each technology from a discipline point of view, thus providing a fundamental reason to support Sætra and Danaher’s (2022) concern –and so opposing to Llorca Albareda and Rueda’s (2023) relativisation of it–. In turn, we will discuss some key insights of both of their stances on tech ethics proliferation and draw some guidelines for tech ethics in practice.

2 On the Statute of Technology Ethics: A Disciplinary Clarification

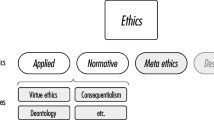

The ethics of technology is commonly deemed as an applied ethics (Franssen et al., 2023) (Gordon & Nyholm, 2024), and this is also the conceptualization that Sætra and Danaher (2022) uncritically subscribe in their paper. While there are reasons why ethical reflection on technology is taken as a task belonging to applied ethics, it is however not proper to speak of tech ethics as an applied ethics. To clarify this, it is necessary to briefly review what applied ethics is and what technology as an object of ethics significance is.

Whereas ethics, as a philosophical discipline, consists in the critical-rational reflection on morality (Román Maestre, 2016), applied ethics concerns a particular level of such activity, namely: the grounding of moral action regarding specific fields of human activity Emerging from the renewal of ethics’ practical commitment (Kettner, 2003) –the historically known “applied turn” of ethics (Cortina, 2003)–, and thus responding to the need to orient human decisions and actions in real life, applied ethics is a form of moral philosophy that attends to particular moral problems and situations that appear in the different spheres of our activity, understood in terms of “practices” (MacIntyre, 2019). Hence, technology and its subfields of activity have come to be contemporarily taken as a matter of applied ethics.

Note that we refer to human activities (as practices) rather than broadly to “particular circumstances”(Sætra & Danaher, 2022, p.3) to signal the territory of applied ethics. The difference is key to a right ‘application’ of ethical reflection, which is that conforming with the “critical hermeneutics” model of applied ethics (Cortina, 1996). This is far from the traditional casuistry models (Arras, 1990) that Sætra and Danaher (2022) stick to, and that correspond to the externalist and internalist approaches against which Llorca Albareda and Rueda (2023) alert. Unlike what these methodologically imply, the applied exercise of ethics requires taking critically into account the specific ends –the “internal goods” (MacIntyre, 2019, p.234)– and values that define the human activity in relation to which the grounding of decisions and actions is undertaken. That is, reflection must be contextualised in the (revisable) particular teleological and axiological framework of the practice to which the courses of action needing moral grounding are circumscribedFootnote 2.

Now, when it comes to technology and its subdomains of activity, these ends and values will ultimately correspond to those of the practices technology aims to serve. The reason has to do with the –albeit non-neutral (Verbeek, 2005, 2011)– instrumental condition of technology, that is, in the fact that it is an activity whose internal good is of a teleologically subordinated kind. In effect, the specific end of technology –the one defining its reason of being, its ‘what for’– is external to itself (Ortega y Gasset, 2004), for it is directed at the purposes of other human activities, concerning which it is actually to be a means. So, the applied exercise of ethics signifies, for the case of technology, a critical hermeneutics of the human activities technology is due to.

In disciplinary terms, this means that the statute of the ethics of technology corresponds to that of an applied ethics subsidiary of the human activities that technology aims at serving. Therefore, it is inaccurate to define tech ethics as just an applied ethics and thus taking technology (and its subdomains of activity) as the (direct) field of ‘application’. Creating specific-domain ethics for each technological field (and its artifacts) privatively –i.e., uncorrelated to any particular practice they are ultimately to respond to–, is indicative of such an error. This is the fundamental reason why tech ethics proliferation, in which the delimitation of domains of inquiry falls within that rationale –think of AI ethics, robot ethics, information ethics or data ethics, but even of that “other subdomains” like Nanoethics (Llorca Albareda & Rueda, 2023, p.2)–, is disciplinary mistaken: it is in conflict with the kind of subsidiary application of ethics that technology requires.

3 Conclusions for the Tech Ethics in Practice

Let us now outline two main implications of this disciplinary clarification for tech ethics in practice, that is, regarding how should it be organized.

First, the demarcation of domains of technology ethics should respond not so much to the different technologies but to the human activities they are directed at.

This entails that, concerning technology, the key question to delimitate regional ethics –and the corresponding logic for “choosing tech ethics” (Sætra & Danaher, 2022, p.19) – does not rely on the novelty or exclusiveness of the ethical issues of the particular technologies, i.e., on “what makes a particular technology distinct from something already covered by an existing ethics” (Sætra & Danaher, 2022, p.6). In turn, though, neither does it sustain the postphenomenological-inspired (Rosenberger & Verbeek, 2015) objection against such criterion advanced by their critics, who appeal to technological mediation as a reason for taking each type of technology as an object of particular ethical attention (Llorca Albareda & Rueda, 2023, p.4). Taking into account technological mediation does indeed demand an ethical approach that proceeds through a critical hermeneutics of the (mediated) activities, rather than just placing the focus on the artifact itself.

Besides, a disciplinary approach to tech ethics proliferation reframes or even dissolves some problems that have been pointed out in its regard by Sætra and Danaher’s (2022) consequentialist evaluation of the matter, as the “Demarcation Problem”, which critics have directed much effort to refute by disproving the empirical assumptions behind it (Llorca Albareda & Rueda, 2023). Inasmuch the activities at which technology aims to serve can be, in a critical hermeneutical sense, well-defined, their boundaries are not a constitutive problem for the exercise of ethicsFootnote 3.

The second implication of our disciplinary clarification has to do with the articulation of ethics within the technological activity, that is, with the configuration of the so-called “engineering ethics” (Sætra & Danaher, 2022), which can no longer be understood and exercised as traditionally done, that is, restrictively as an ethics of profession (Franssen et al., 2023), detached from the particular practices the engineering-activity is due to. This does not necessarily entail dismissing a lax categorization of tech ethics into sub-ethics of technologies to refer to the exercise of articulating ethics within each of the fields of technoscientific activity. However, it is fundamental to exercise engineering ethics broader as an ethics of technology that concerns engineers for being suppliers of means for specific human practices.

To conclude: from a disciplinary perspective, the ethics’ historical transition from Technology to technologies (Brey, 2010) needs now to be completed with a last turn to the technologically mediated human practices.

Notes

Among its multiple senses (Mitcham, 1994), this notion is here and in the rest of the paper broadly meant to refer to technology both as an activity and as an artifact.

This must of course be in line with the principles of civic ethics (justice and dignity) and dialogical ethics (recognition of the affected subjected as valid interlocutors) (Cortina, 2003).

Note that, in turn, this also helps clarify unsolved tensions in previous arguments, as why medical ethics has not proliferated in subfields corresponding to the different medical branches, in contraposition to technology (Sætra & Danaher, 2022, p.21): as a domain of ethics, medicine differs from technology, in that it is not teleologically subordinated.

References

Arras, J. D. (1990). Review: Common Law Morality. The Hastings Center Report, 20(4), 35–37.

Brey, P. (2010). Philosophy of technology after the empirical turn. Techné, 14(1), 36–48.

Cortina, A. (1996). El estatuto de la ética aplicada. Hermenéutica crítica de las actividades humanas. Isegoría, 13, 119–127.

Cortina, A. (2003). El quehacer público de las éticas aplicadas: ética cívica transnacional. In A. Cortina, & D. García-Marzá (Eds.), Razón pública y éticas aplicadas. Los caminos de la razón práctica en una sociedad pluralista (pp. 13–44). Tecnos.

Franssen, M., Lokhorst, G. J., & van de Poel, I. (2023). Philosophy of Technology. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition). Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (Eds.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/technology/

Gordon, J. S., & Nyholm, S. (2024). Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. In The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/ethics-of-artificial-intelligence/

Kettner, M. (2003). Tres dilemas estructurales de la ética aplicada. In A. Cortina & D. García-Marzá (Eds.), Razón pública y éticas aplicadas. Los caminos de la razón práctica en una sociedad pluralista (pp. 145–158). Tecnos.

Llorca Albareda, J., & Rueda, J. (2023). Divide and Rule? Why ethical proliferation is not so Wrong for Technology Ethics. Philosophy and Technology, 36(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-023-00609-8

MacIntyre, A. (2019). Tras la Virtud. Austral.

Mitcham, C. (1994). Thinking through Technology. The path between Engineering and Philosophy. The University of Chicago Press.

Ortega, J. (2004). Meditación de la técnica y otros ensayos sobre ciencia y filosofía (8a). Revista de Occidente en Alianza Editorial.

Román Maestre, B. (2016). Ética de los servicios sociales. Herder.

Rosenberger, R., & Verbeek, P. P. (2015). A Field Guide to Postphenomenology. In R. Rosenberger, & P. P. Verbeek (Eds.), Postphenomenological investigations: Essays on human-technology relations. Lexington Books.

Sætra, H. S., & Danaher, J. (2022). To Each Technology Its Own Ethics: The problem of Ethical Proliferation. Philosophy & Technology, 35(93), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-022-00591-7

Verbeek, P. P. (2005). What Things Do: Philosophical reflections on technology, agency, and design. The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Verbeek, P. P. (2010). Accompanying technology: Philosophy of technology after the ethical turn. Techne: Research in Philosophy and Technology, 14(1), 49–54.

Verbeek, P. P. (2011). Moralizing technology: Understanding and designing the morality of things. The University of Chicago Press.

Acknowledgements

We are greatly indebted to Dr. Begoña Román for her fruitful insights and contributions to this discussion.

Funding

This work has been partially supported by project ROBassist: Personalized and responsible robotized assistance (202450E060) funded by CSIC.

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this work. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Júlia Pareto and all authors commented on and critically revised the previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pareto, J., Torras, C. To each Technology Its Own Ethics? A Reply to Sætra & Danaher (and Their Critics). Philos. Technol. 37, 107 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-024-00798-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-024-00798-w