Abstract

The metaverse is equivocal. It is a science-fictional concept from the past; it is the present’s rough implementations; and it is the Promised Cyberland, expected to manifest some time in the future. The metaverse first emerged as a techno-capitalist network in a 1992 science fiction novel by Neal Stephenson. Our article thus marks the metaverse’s thirtieth anniversary. We revisit Stephenson’s original concept plus three sophisticated antecedents from 1972 to 1984: Jean Baudrillard’s simulation, Sherry Turkle’s networked identities, and Jacques Lacan’s schema of suggestible consumers hooked up to a Matrix-like capitalist network. We gauge the relevance of these three antecedents following Meta’s recent promise to deliver a metaverse for the mainstream and the emergence of blockchain-oriented metaverse projects. We examine empirical data from 2021 and 2022, sourced from journalistic and social media (BuzzSumo, Google Trends, Reddit, and Twitter) as well as the United States Patent and Trademark Office. This latest chapter of the metaverse’s convoluted history reveals a focus not on virtual reality goggles but rather on techno-capitalist notions like digital wallets, crypto-assets, and targeted advertisements. The metaverse’s wallet-holders collect status symbols like limited-edition profile pictures, fashion items for avatars, tradable pets and companions, and real estate. Motivated by the metaverse’s sophisticated antecedents and our empirical findings, we propose a subtle conceptual re-orientation that respects the metaverse’s equivocal nature and rejects sanitised solutionism. Do not let the phantasmagorical goggles distract you too much: Big Meta is watching you, and it expects you to become a wallet-holder. Blockchain proponents want this as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The metaverse emerged in 1992 as a parodic, techno-capitalist concept from a science fiction novel: Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson. The novel’s antecedents include sophisticated conceptual texts from the 1970s and 1980s about simulation, networked identities, and capitalist networks by Jean Baudrillard, Sherry Turkle, and Jacques Lacan. Business and engineering researchers typically discuss the metaverse not as a parodic, science-fictional concept but as an earnest, actual thing (Dincelli & Yayla, 2022; Dwivedi et al., 2022; Kliestik et al., 2022)—an immersive virtual world, populated with avatars. This “thing” of theirs, however, does not enjoy mainstream adoption, since “the implemented applications are mainly at the prototype level” (Narin, 2021, p. 23). Hence, the latest cast of metaverse developers discuss their metaverse—the one expected to captivate consumers and social media users—as a future telos, perhaps ten years out of reach (Clegg, 2022; Floridi, 2022).

Already, one can observe that the metaverse is split in three: past, present, and future. There is the past’s parodic, science-fictional concept (Stephenson, 1992). There are earnest, prototypical implementations from the present that are reputedly “boring” (Zuckerman, 2021), “sad, lonely, expensive” and resemblant of “a cartoony wasteland” (Manjoo, 2022). Last but not least, there is the Promised Cyberland—an awesome, captivating metaverse that is yet to arrive (Clegg, 2022; Elmasry et al., 2022).

Literature scholars often interpret the metaverse’s origin, Snow Crash (Stephenson, 1992), as a parody, a self-parody, or a satire. This is not surprising: the novel’s mock-heroic, computer hacker protagonist is named Hiro Protagonist, and the metaverse’s full-time inhabitants are goggle-wearers nicknamed gargoyles. Gargoyles are “embarrassing” creatures that “wear their computers on their bodies, broken up into separate modules that hang on the waist, on the back, on the headset. They serve as human surveillance devices, recording everything that happens around them” (Stephenson, 1992, ch. 15). Heuser (2003, p. 171) interpreted Stephenson’s metaverse as a parody of the “cyberpunk plot device of virtual reality”, which was “already stale” in the 1990s. Swanstrom (2010, p. 54) characterised Snow Crash as “a scathing satire of social fragmentation” with a focus on techno-capitalist networks’ “rules of isolation” and atomised individuality. Morttiz (2013, p. 109) later read Snow Crash as a parody of techno-capitalism’s beneficiaries. According to her, the novel “questions the so-called ‘development’ in postmodern societies, more specifically, the North American one, through its parody” and its hyperbolic degeneracy.

In 2021, Mark Zuckerberg neglected the metaverse’s parodic origin. He tried to depict the metaverse as something bizarrely earnest. This is how the metaverse became a cause of speculation, just before its thirtieth anniversary (Fig. 1): Facebook, Inc. renamed itself Meta Platforms, Inc. and proclaimed the metaverse its future (Zuckerberg, 2021). Meta’s earnest metaverse attracted oracular, fiscal pronouncements (Elmasry et al., 2022; Ghose et al., 2022; Moy & Gadgil, 2022; Weking et al., 2023); yet, at the same time, it suffered satirical comparisons with the Matrix (from the eponymous science fiction film) on social media platforms (Clegg, 2022). We thus encounter an equivocation: the metaverse is potentially profitable and utopian, and the metaverse is extractive and dystopian.

A dystopian/utopian, ugly/beautiful, horror/comic ambivalence is present in Snow Crash (Morttiz, 2013; Stephenson, 1992; Swanstrom, 2010). Ethan Zuckerman (2021)—a sardonic, early metaverse developer, and a former director of MIT’s Center for Civic Media—interpreted the “beautiful virtual world” from Snow Crash as a comic-pathetic alternative to the physical world. “The outside world had become so shitty”, Zuckerman noted, “that no one wanted to live in it”. The Acceleration Studies Foundation discussed this same notion, albeit in earnest, in 2007. In their imagined future, people “might live increasingly Spartan lives in the physical world, and rich, exotic lives in virtual space—lives they perceive as more empowering, creative and ‘real’ than their physical existence, in the ways that count most” (Smart et al., 2007). As an escapist enterprise, “a virtual space beyond (meta-) our fractured and hurtful reality” (Žižek, 2022a), or an “architecture of exit” (Smith and Burrows, 2021), the metaverse could become just another reboot of “Plato’s shadows on a cave wall” (Zuckerman, 2021).

The Lacanian-Hegelian philosopher, Slavoj Žižek (2022a), interpreted the metaverse equivocally as the Matrix and as Mark Zuckerberg’s “neo-feudal manifesto”. According to Žižek (2022a), the metaverse is conditioned not by goggles, gadgets, and computer-generated graphics. It is conditioned, rather, by extra-rational profit—Marxian Mehrwert, Lacanian plus-de-jouir—derived from the equivocal enjoyment/suffering of its human subjects. This is a key theme from the Matrix film series: as long as humans are hooked up to it, the Matrix network is indifferent to distinctions between enjoyment and suffering, just as it is indifferent to distinctions between “virtual reality” and “real reality” (Baudrillard, 1994 [1981]; Chalmers, 2016; Žižek, 2022a). The equivocality is crucial (Berente et al., 2011; Rolla et al., 2022; Weick, 1990).

Our approach to the metaverse respects its equivocal nature and rejects sanitised solutionism (Baudrillard, 2003 [2000]). Although we are tempted by the pun, we do not examine the metaverse from a meta- position, as would a metaphysician. Likewise, we do not offer a cosmology of the metaverse that details phenomena from Meta’s Horizon Worlds or the Bored Ape Yacht Club’s Otherside. We instead examine contemporary discourse about the metaverse in parallel with the metaverse’s sophisticated antecedents, conceived by Baudrillard (1994 [1981]), Turkle (2004 [1984]), and Lacan (1978 [1972]). These are as follows: simulation,Footnote 1 networked identities, and suggestible consumers hooked up to a Matrix-like capitalist network. This parallel (para-) position, true to Stephenson’s Snow Crash (1992), entails parody (Nobus and Quinn, 2005), and—thanks to the Big Other of online surveillance (Khader, 2022; Zuboff, 2015)—a modest touch of paranoia as well.

Following a review of texts by Baudrillard, Turkle, and Lacan that predate Snow Crash (Stephenson, 1992), as well as an empirical inquiry, we propose a subtle conceptual re-orientation (Fig. 7). We also contribute a didactic, reduced schema of the techno-capitalist metaverse (Fig. 8) and a series of hermeneutic twists. According to our reading, the metaverse is Meta’s promised future, yet it is also an old idea. (To paraphrase Madonna, we already live in an artificial-material world, and we are its artificial-material girls.) Meta expects its users to become crypto-asset wallet-holders, not just Oculus goggle-wearers (Pupolizio, 2021; Zuckerberg & Bilyeu, 2022); Oculus’s viewer is the viewed (or the surveilled) (Meta, 2022a); the consumer chooses (a plethora of tokenised goods) and is chosen (by targeted advertisements) (Murphy, 2022); and finally, the avatar’s interactions entail both self-expression and an affected self-impression (Riches et al., 2020; Wiederhold, 2021).

We encourage fellow academics to attend to the metaverse’s techno-political, pathematic, and parodic notions—not only the techno-optimistic, the taxonomic, and the earnest (Elmasry et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2021; Smart et al., 2007).

1.1 Apologia: Simulation and Equivocality

Reality imitated fiction on 21 June 2022, when Stephenson’s blockchain-based metaverse project, LAMINA1, co-founded the Metaverse Standards Forum together with Meta, Microsoft, NVIDIA, and others. In response to this development—the blurring of science fiction and technology in the making (Gray, 2007; Lacan, 2014 [1974]; Smith & Burrows, 2021)—we treat the metaverse as something that “generates confusion” (Floridi, 2022). The metaverse is as follows: (a) a comic-pathetic, techno-capitalist concept from 1992, (b) a Big Tech naming event from 2021, accompanied by “prototype level” implementations (Narin, 2021), and (c) a competition among developers to transform mainstream consumers and social media users into the future’s suggestible wallet-holders (with the requisite, phantasmagorical goggles).

Business and engineering communities’ taxonomic classifications and linear narratives of technological progress commonly acknowledge Snow Crash as the origin of the metaverse (Dincelli & Yayla, 2022; Elmasry et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2021). They identify elaborate and interactive gaming worlds like Second Life, World of Warcraft, and Minecraft as the Promised Cyberland’s precedents (Chaturvedi et al., 2011; Dionisio et al., 2013; Vitzthum et al., 2011), as well as the mass adoption of Internet-connected mobile devices, the Facebook company’s 2014 acquisition of Oculus VR (Egliston & Carter, 2022c; Stone, 2017), and “augmented reality” games like Pokémon GO (Paavilainen et al., 2017; Rauschnabel et al., 2017).

Taxonomies and technological progress narratives are earnest and informative, but they frequently ignore the metaverse’s equivocal nature, and they omit salacious historical details. (To paraphrase Hamlet, there are more things in the virtual Heaven and Earth than are dreamt of in business and engineering taxonomies.) Sex-driven commerce, for instance, is a fixture of the Second Life Marketplace (Brown, 2021; Zuckerman, 2021). Coupled with uncertain or illicit desires, sex-driven commerce is also present in science-fictional depictions of immersive virtual worlds: see, for example, Demolition Man (1993) and Minority Report (2002), or the “San Junipero” (2016) and “Striking Vipers” (2019) episodes from the parodic Black Mirror series. This prominent, Second Life phenomenon—or popular, science-fictional theme—is notably absent from most academic texts about the metaverse (Narin, 2021), especially texts produced by business and engineering communities (Dincelli & Yayla, 2022; Dwivedi et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2021).

In 2006, the Acceleration Studies Foundation invited earnest proponents of “Industry 4.0” (Morozov, 2019; Narin, 2021), “technological solutionism” (Morozov, 2013), and/or “technological liberalism” (Dotson, 2012) to the Metaverse Roadmap Summit. The Summit aimed to solve the virtual world’s problems and to discuss putatively serious use-cases, such as a virtual Darfur to help non-refugees “understand” the refugee experience (Zuckerman, 2021). “How might we use the various forms of the metaverse to guide our response to global warming?” the Foundation asked (Smart et al., 2007). “How might we use these systems to avert a war, improve an election, reduce crime and poverty, or put an end to human rights abuses?”

At the time, the best-known metaverse project—the Second Life Marketplace—facilitated a “thriving kink scene” and sold “digital bondage gear” (Zuckerman, 2021). There is no mention of this in the “Metaverse Roadmap”, published after the Summit by the Acceleration Studies Foundation. The “Roadmap” cites the Second Life Marketplace’s “$1.5M of daily economic transactions”, but it does not specify what is bought and sold (Smart et al., 2007). The same can be said for the recent business and engineering texts (Dincelli & Yayla, 2022; Dwivedi et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2021): they are typically earnest, wholesome, and sanitised (Baudrillard, 2003 [2000]). The mysterious “inhumanity of desire” is omitted (Hietanen et al., 2020); the homo demens—in-between fiction and rationality—is not acknowledged (Cronin & Fitchett, 2022); “the border between games and adult play” is not inspected or interrogated (Harviainen & Frank, 2018).

We are motivated, in part, by these absences and omissions; and we look to science fiction for supplements (Baudrillard, 1994 [1981]; Gray, 2007; Lacan, 2014 [1974]).Footnote 2 In a discussion of virtual reality (and Michel Houellebecq’s horrific-pathetic science fiction), Žižek (2001) acknowledged that, outside academia, “pornography is perceived as the predominant use of cyberspace”. Virtual reality therefore promises “new experiences of pleasure” as well as new “possibilities of torture”—another equivocation. A recent episode from Netflix’s You, “And They Lived Happily Ever After” (2021), parodied suburban “lifehackers” with a virtual reality pod in their garage: “The porn is spectacular”. Stephen Spielberg’s Minority Report (2002) also parodied the desires of metaverse consumers. A commercial, virtual reality parlour allowed men to experience “sex as a woman”. Women, meanwhile, could enjoy/suffer intimate relations with “their favourite soap star”. “I wanna kill my boss”, requested one eager customer. Another paid to receive compliments from people that he respects.

There is a horrific-pathetic truth to these characters’ wishes (Cronin and Fitchett, 2022; Hietanen et al., 2020), yet this is rarely acknowledged by the metaverse’s business and engineering literature (Dincelli & Yayla, 2022; Dwivedi et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2021). The virtual reality parlour from Minority Report (2002), like the parodic metaverse from Snow Crash (Stephenson, 1992), is not just technological and economical; it is an aggregate of equivocal enjoyment/suffering. This is, as Žižek (2022a) put it, a “fundamental Lacanian thesis”.

Our article respectfully sidelines the web of acronyms weaved by taxonomers, engineers, and business consultants, such as VR (virtual reality), AR (augmented reality), MR (mixed reality), XR (either xReality or extended reality), XE (expanded experience), VRE (virtual reality experience), and HCI (human-computer interaction). Our engagement with Baudrillardian simulation—instead of “virtual reality” (Milgram and Kishino, 1994; Skarbez et al., 2021), “xReality” (Rauschnabel et al., 2022), “Reality+” (Chalmers, 2022), “expanded experience” (Floridi, 2022), “extended cognition” (Smart, 2022), “virtual reality experiences” (Rolla et al., 2022), or “virtual world platforms (the predecessors to today’s metaverse applications)” (Erickson, 2022)—is very deliberate.

Baudrillardian simulation connotes not just virtual worlds; it also entails extractive techno-capitalist networks and participants’ uncritical dispositions (Baudrillard, 1994 [1981]; Deleuze & Guattari, 1994 [1991]; Turkle, 2009). Texts about Baudrillardian simulation therefore encourage a focus on the recent emergence of blockchain-oriented metaverse projects and crypto-asset wallet-holders (Belk et al., 2022; Gilbert, 2022; Martin et al., 2022). Crypto-asset wallet-holders include (but are not limited to) self-parodic “degens” (Sartoshi, 2022)—short for degenerates—and the Otherside’s affluent and uncritical “apes” (Muniz & Segall, 2022). Since the Bored Ape Yacht Club’s Otherside is one of the best-funded, blockchain-oriented metaverse projects (Jeffries, 2022), it would be unwise to dismiss “apes” as marginal or inconsequential. According to a recent, pre-registered survey of crypto-asset wallet-holders, the so-called Dark Tetrad is statistically significant. The Dark Tetrad consists of “Machiavellianism, subclinical narcissism, subclinical psychopathy, and subclinical sadism” (Martin et al., 2022). Smith and Burrows (2021) selected a similar, sombre palette for their portrayal of crypto-asset enthusiasts, creators of tradable virtual galaxies, neo-reactionary thought, and “billionaire libertarians”.

Suffice to say, Baudrillardian simulation does not confine researchers to the earnest, sanitised metaverse (Smart et al., 2007). It can also account for an uncritical, probable metaverse in which “you find yourself surrounded by zombies” and then “you kill them with the usual chainsaw” (Floridi, 2022). It remains open to another iteration of Plato’s Cave or das Opium des Volkes (Becker, 2022; Marx, 1844; Zuckerman, 2021).Footnote 3 On a broader note, simulation is a term used by MIT’s computer scientists (Turkle, 2009), media theorists (Baudrillard, 1994 [1981]; Chalmers, 2016; Žižek, 2020, 2022a), metaverse developers from the 1990s and 2000s (Smart et al., 2007; Zuckerman, 2021), metaverse researchers (Kliestik et al., 2022; Maharg & Owen, 2007; Nguyen, 2022), and Simulation Nation. The latter is a website for metaverse enthusiasts, run by a “mostly human” cyberpunk named Johnny Android and Hiro Protagonist from Snow Crash (Android & Protagonist, 2022). (The website’s description is facetious, obviously.)

Our engagement with Baudrillardian simulation provoked a shift away from earnest, open-source “virtual world platforms” (Erickson, 2022), inclusive and accessible Google Cardboard goggles (Oakley, 2017), and non-financialised gaming worlds (Smart et al., 2007). It encouraged a turn towards techno-capitalism’s latest cast of blockchain enthusiasts, wallet-holders, and self-parodic degens (Belk et al., 2022; Martin et al., 2022; Smith & Burrows, 2021). This is effectively a return to the site of Snow Crash (Stephenson, 1992).

1.2 Background: From Science Fiction to Visions of the Future

Snow Crash (Stephenson, 1992) depicted the metaverse as inhabited by avatars and governed by a Big Tech company named the Global Multimedia Protocol Group. Stephenson’s metaverse could be described in plain terms as an immersive digital marketplace (Kliestik et al., 2022). Much like the contemporary, blockchain-based Decentraland (Goanta, 2020), Stephenson’s metaverse offered virtual real estate. Its inhabitants, like the apes and degens of today (Belk et al., 2022; Muniz & Segall, 2022; Ryskeldiev et al., 2018), often used crypto-currencies, after the United States dollar suffered inflation and fell into disrepute.Footnote 4 On 8 June 2022 (thirty years after Snow Crash), Stephenson launched his first blockchain-based metaverse project, LAMINA1.

The techno-capitalist billionaire, Peter Thiel, named Stephenson’s fiction required reading for his employees at PayPal (Thiel & Masters, 2014). Thiel joined the Facebook company’s board of directors in 2005, then he served as a Meta director until 2022. Thiel resigned from Meta’s board in order to focus on libertarian activism and “Make America Great Again” campaigns (Murphy & Stacey, 2022; Smith & Burrows, 2021). Thiel’s favourite book from the 1990s, The Sovereign Individual (Davidson & Rees-Mogg, 1999), unironically endorsed the metaverse concept (Gilbert, 2022). Davidson and Rees-Mogg (1999) aligned the metaverse with the “cybereconomy” (p. 30) and “cybercommerce” (p. 179). They envisioned a future in which the metaverse’s wealthy “cybercommunities” can “operate their own economic havens much as free ports and free trade zones are licensed to do today” (p. 30). This political vision is—like that of Snow Crash and The Matrix—“apocalyptic” (p. 14). A class of crypto-asset holders is expected to thrive while the “cyberpoor” masses suffer hyper-inflation (pp. 42–49). Davidson and Rees-Mogg (1999) celebrated this vision, in earnest.

The metaverse conceived in the 1990s—parodically by Stephenson (1992), then enthusiastically by Davidson and Rees-Mogg (1999)—is a techno-capitalist society with impressive class divisions (Robinson, 2017). This conception remains relevant today (Egliston & Carter, 2021, 2022b, 2022c; Sadowski, 2020), as does the prospect of a super-sized “digital divide” (Floridi, 2022). According to a prediction by Citi Bank, the metaverse is destined to become a market worth $8 to $13 trillion by the year 2030 (Ghose et al., 2022). J.P. Morgan portrayed the metaverse as a $1 trillion yearly revenue opportunity (Moy & Gadgil, 2022). “Watch retailers combine sensors, computer vision, AI, augmented reality, and immersive and spatial computing”, McKinsey & Company and the World Economic Forum jointly enthused, “to wow customers with video-game-like experience designs” (Corbo et al., 2022). The Forbes Business Development Council envisioned a “business-to-avatar” model for the metaverse—a variation on the well-known business-to-consumer model (Vargo, 2022). Here, we encounter another equivocation: Forbes also described Meta as “the S&P 500’s worst performer of 2022 as losses near 75%” (Saul, 2022).

This, in short, is the business community’s predominant vision of the metaverse: simulation plus further economisation (Belk et al., 2022; Çalışkan & Callon, 2009). In concrete terms, they envision immersive virtual worlds for proprietors, retailers, advertisers, and consumers (Bourlakis et al., 2009; Kim, 2021; Kliestik et al., 2022; Weking et al., 2023). Žižek (2022a), unsurprisingly, interpreted this vision as a decision to remain “in” the Matrix, to not radically disrupt the techno-capitalist status quo. Zuckerman (2021) reflected on the year that he became a metaverse developer and stated, “Zuck’s metaverse looks pretty much like we imagined one would look like in 1994”. Zuckerman’s statement is equivocal, since it refers to both the look of Meta’s computer-generated graphics and the look of Meta’s political vision. “Facebook’s promised metaverse”, he concluded, “is about distracting us from the world it’s helped break”.

1.3 Methods and Assumptions

We do not treat the metaverse—Big Tech’s latest innovation—as a new concept (Clegg, 2022; Heuser, 2003; Kim, 2021). We instead assume that, in 2022, the metaverse does not seriously challenge conceptions of simulation, networked identities, and capitalist networks that are decades old. To tease out support (or challenges) for this assumption, we engaged with conceptual texts that predate Stephenson’s Snow Crash (1992), then we conducted an empirical inquiry. We selected sophisticated texts written by authors that engage with both literary fiction and social science: Jean Baudrillard (1990 [1979], 1994 [1981]), Sherry Turkle (1978, 2004 [1984], 2009), and Jacques Lacan (1978 [1972], 2014 [1974]). We examined recent empirical developments that pertain to the metaverse as technology “in the making” (Latour, 1987); then, we adapted the work of Baudrillard, Turkle, and Lacan to produce a didactic, reduced schema (Fig. 8) and a sequence of propositions.

Our article conforms to the “theory adaptation” template offered by Jaakkola(2020, p. 23). As is common within Science and Technology Studies (STS), the concept under investigation is an inextricable tangle of economic, social, and technical subject matter (Callon, 1986; Latour, 1987; Law, 1987; Williams and Edge, 1996). The science-fictional depictions of the metaverse add to this tangle the techno-political, the pathematic, and the parodic (Gray, 2007; Morttiz, 2013; Stephenson, 1992). A multi-disciplinary approach to the metaverse is inevitable; hence, our article is addressed to concept-driven market studies (Hietanen et al., 2022; Hirschheim, 2008; Jaakkola, 2020), Turkle’s field of STS (Borup et al., 2006; Jasanoff & Kim, 2009; Latour, 1987), and philosophical sub-fields of information systems research (Floridi, 2022; Pignot, 2016; Willcocks & Mingers, 2004).

We depart from business and engineering communities’ prominent conceptions of individuals as autonomous, network-independent agents that acquire affordances, competencies, and solutions via technology (Ahlberg et al., 2022; Dotson, 2012; Hietanen et al., 2022). We instead assume that human subjects are constituted and affected by socio-technical networks (Callon, 1986; Latour, 2005; Pignot et al., 2020). We thereby follow Turkle (1978) and Lacan (1991 [1970]), who described societies (les discours) as networks that generate expectations, fantasies, role descriptions, and identities—things that are not necessarily meaningful, satisfying, or stable.

Following Baudrillard, Turkle, and Lacan, we do not prescribe ways for engineers, business consultants, and policy-makers to make the virtual world a better place (Ahlberg et al., 2022). Our approach is not “romantically agentic” (Hietanen et al., 2022, p. 167), “solutionist” (Morozov, 2013), or faithful to “technological liberalism” (Dotson, 2012). We instead encourage the metaverse’s philosophical researchers to engage with science fiction (Gray, 2007; Lacan, 2014 [1974]), futuristic visions (Becker, 2022; Borup et al., 2006; Gray, 2020), socio-technical imaginaries (Jasanoff and Kim, 2009; Smith & Burrows, 2021), and—even if it seems senseless—the metaverse’s cartoonish phenomena (Baudrillard, 1994 [1981]; Turkle, 2004 [1984]). The senseless and the imaginary, with respect to the metaverse, are consequential (Becker, 2022; Luckey, 2022; Smith & Burrows, 2021).

Instead of proclaiming that individuals “change the world” (either real or virtual), we observe techno-capitalism’s ability to foster peculiar dreams of autonomy and control (Baudrillard, 2001 [1999]; Lacan, 1991 [1970]; Proto, 2013), as well as the production of “human” avatar-identities as tradable commodities (Heister & Yuthas, 2020; Woodbury, 2021). With respect to techno-capitalist networks like the metaverse, the so-called user is used (for monetised personal data), the viewer is viewed (to determine if advertisements capture their attention), and the consumer-subject is subjected (to an array of purchase suggestions, incentives, and nudges) (Egliston & Carter, 2021, 2022b, 2022c; Fuchs, 2019, 2021). As Rosenberg (2022) put it, the metaverse is “an environment that has the potential to act upon you more than you act upon it”.

The relation between human actors and techno-capitalist networks is knotty and complicated (Morozov, 2019; Sadowski, 2020; Žižek, 2020, 2022b). Paul Smart (2022) recently conceived the metaverse’s “hybrid cognitive circuits” as the interplay of “organismic” human bodies and “extra-organismic” goggles. With exceptional foresight, Turkle (2004 [1984], p. 173) referred to this commingling of humans and machines as “intimate” and affecting, rather than “instrumental” or utility-based. Baudrillard (1994 [1981], pp. 111–119), likewise, discussed “erotic machinery” and the “body confused with technology”—not something that is neatly distinguished as an individual user plus a useful technological tool. Decades later, Faulkner (2000, pp. 761–762) acknowledged that “intimacy with computers” and the inextricable link between identity and technology are common, social-scientific tropes. The tropes extend to “sensual and spiritual” connections as well as “emotional comfort and aesthetic pleasures”. Hence today, social relations can be conceived as “network effects” (Law, 1992, p. 379); and so, too, can identities (Turkle, 1978, 1995, 2004 [1984]).

If the network is a blockchain-based marketplace, then identities are not merely constructed and quantified (Sharon and Zandbergen, 2017); identities can be tokenised and purchased as commodities (Heister & Yuthas, 2020; Woodbury, 2021). The metaverse exemplifies these techno-capitalist notions, since permission to assume an avatar-identity (like a Bored Ape) is usually stored within a wallet (or a registered account), and the avatar-identity’s possible attributes are limited and determined by the network (Muniz & Segall, 2022; Sartoshi, 2022). Hence, one encounters the following prompt at the entrance of metaverse projects by the Shiba Inu community and the Bored Ape Yacht Club: “Connect Wallet”.

To date, metaverse research has mostly focussed on virtual worlds (Dincelli & Yayla, 2022; Kliestik et al., 2022; Narin, 2021), and metaverse developers like Meta and Microsoft evidently wish to sell virtual reality goggles and other human-computer interaction devices; but these companies expect something more than virtual lurkers, loiterers, and spectators (Zuckerberg & Bilyeu, 2022). Goggles, we claim, are the red herring. Wallet-holders are the mega-shoal of Atlantic herring—perfect for the commercial trawlers. Unfettered economisation—the tokenisation of physical and digital objects, tangible and intangible assets, productive and unproductive labour, professional and even personal relations (Heister & Yuthas, 2020; Lacity & Treiblmaier, 2022; Woodbury, 2021)—parts the Red Sea. This techno-capitalist path leads not just blockchain enthusiasts to their Promised Cyberland (Becker, 2022; Belk et al., 2022). In parallel with the parodic and the pathematic, the techno-capitalist path beckons philosophical research.

2 Theory: The Metaverse’s Conceptual Antecedents

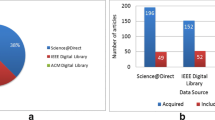

Academic texts about the metaverse, especially those produced by business and engineering communities (Narin, 2021, p. 18), prioritise simulation (virtual worlds), networked identities (avatars), and capitalist networks (“Industry 4.0”). These three concepts predate Stephenson’s Snow Crash (1992); hence, we refer to them as the metaverse’s antecedents. Figure 2 presents these three antecedents. It uses arrows to depict the academic literature’s default conceptual orientation, or the current order of priorities (Adams, 1994).

We derived an understanding of the metaverse’s conceptual antecedents from Jean Baudrillard, Sherry Turkle, and Jacques Lacan. These theorists each assumed that social networks—both physical and virtual—involve suggestibility, habituation, and day-to-day senselessness (Nobus & Quinn, 2005). This assumption achieved a special relevance in the Web 2.0 era of Facebook, Instagram, and mobile gaming, not to mention Behaviour Design and Persuasive Technology (Fogg, 2003; Hari, 2022; Turkle, 2017).

Baudrillard is “the theorist of simulation” (Merrin, 2005, p. 115). His book, Simulacra and Simulation (1994 [1981]), inspired the Matrix film series (Constable, 2013; Merrin, 2005).Footnote 5 Baudrillard’s work is well-known among researchers of techno-capitalist networks, virtual reality, gaming worlds, and other media-technological systems (Abbinnett, 2008; Bishop & Phillips, 2007; Coulter, 2007; Gane, 1991). Scholars have already acknowledged, albeit briefly, links between Baudrillardian simulation and the metaverse (Ilyina et al., 2022; Rospigliosi, 2022).

Turkle is the founding director of the MIT Initiative on Technology and Self. Like Baudrillard (1994 [1981]), Turkle (2009) wrote about the uncanny ability of simulations to substitute for reality. She dedicated her first book from 1978 to Lacanian schools in Paris and their unflattering, non-utopian conception of human subjects. Turkle’s work thereby constructs a bridge between Baudrillard and Lacan. Turkle’s best-known works about networked identities, avatars, and online profiles—namely, The Second Self (2004 [1984]), Life on the Screen (1995), and Alone Together (2017)—retain a Lacanian influence.

Turkle’s notion of intimate machines resists a clear-cut, utopian separation of technological tools and autonomous, problem-solving users. Turkle (1978, 1995, 2004 [1984]) instead treats individuals’ identities as products of social networks. This notion is explicitly relevant to the metaverse’s avatar-identities—tokenised products like Bored Apes that are registered to crypto-asset wallet-holders, or personalised avatars registered to Meta account-holders (and invited to shop at the new Meta Avatars Store). A wallet (or registered account) allows the metaverse’s inhabitants to prove who they are via what they have (Zuckerberg, 2022b)—a fundamental techno-capitalist notion (Heister and Yuthas, 2020).

Lacan’s work is, unfortunately, a frequent cause of misunderstanding among Anglophone commentators (Aoki, 1995; Nobus & Quinn, 2005), especially those that are committed to popular, utopian notions of agency, self-awareness, self-determination, self-fulfilment, self-improvement, self-ownership, or self-realisation (Dotson, 2012; Hietanen et al., 2022). Lacan is known by some metaverse commentators for le grand Autre (González-Campo et al., 2013; Khader, 2022; Žižek, 2022a)—an equivocal figure that, for paranoiac subjects, becomes the horrific “Big Other” of demand, surveillance, and control (Riches et al., 2020; Zuboff, 2015). In texts from 1970 to 1973, Lacan described how pathematic human subjects are caught up in social networks (les discours). For a putatively normal subject, the identity (ego) is impressionable: it is constituted by social networks and bound up with (dis)satisfaction and occasional senselessness (Lacan, 2005 [1976]). The subject is otherwise an insubstantial wannabe (manque à être) that drifts among status symbols (signifiants)—anything from university credit points to a stereotypical, hot-rodded car (Lacan, 1970, 1991 [1970]). Via metaverse marketplaces, these status symbols can become simulated capital, promoted to suggestible wannabes via targeted advertisements, sold and registered to crypto-asset wallets (Kim, 2021; Rosenberg, 2022; Zuckerberg, 2022b).

Lacan’s capitalist network schema (1978 [1972]) depicts consumer subjection and complicated enjoyment/suffering. It sheds light on the metaverse’s wallet-holders as suggestible, non-utopian choice-makers (Sax & Ausloos, 2021). Lacan’s work has already influenced texts about the metaverse (González-Campo et al., 2013; Khader, 2022; Žižek, 2022a), as well as recent studies of techno-capitalism’s “magical” thinking (Santisteban & Jones, 2022), virtual reality (Benjamin, 2018; Wang, 2021), the platform economy (Pignot, 2021), technology “buy-in” (Pignot et al., 2020), human-computer interaction (Žižek, 2020), crypto-currency (Bjerg, 2016), and “crisis capitalism” (Bjerg, 2014). Lacan’s work is crucial, we believe, for a nuanced and unflattering understanding of the metaverse’s goggle-wearers and wallet-holders as suggestible wannabes.

2.1 Baudrillard and Simulation

Thanks to a twist of fate, the Facebook company’s metaverse announcement coincided with hype about the fourth Matrix film from 2021 (Fig. 3). Journalists’ and bloggers’ headlines played on the coincidence: “What The Matrix reveals about our grim metaverse future”, “Metaverse: Welcome to the Matrix”, “Metaverse = Matrix?”, and so on. Academics associated the metaverse with the Matrix soon afterwards (Alcantara & Michalack, 2023; Hong, 2021; Žižek, 2022a).

In the original Matrix film, the protagonist Thomas A. Anderson hides computer disks in a book that has pages cut out. The book is labelled Simulacra and Simulation. In reality, Simulacra and Simulation is a physically small book by Baudrillard (1994 [1981]); but in the film, the book is very large. This little transgression—a lack of fidelity with respect to reality—ironically complements the book’s contents. Baudrillard’s book and The Matrix each concern a simulated, techno-capitalist realm that is indifferent to classical binary distinctions like the true and the false, the original and the duplicate, the ethical and the unethical, the moral and the immoral, the just and the unjust, the real and the virtual. Hence, Chalmers (2022) uses the phrase “simulation realism” to discuss “perfect”, artificially rendered objects that percipients are likely to accept as “real and not an illusion”. Rolla et al. (2022), likewise, approach “virtual reality experiences” not as illusions but as “allusions”: “the subject acts as if the virtual experiences are real”. Rolla et al. (2022) notably depart from “functionalism” in order to play with equivocality (illusion/allusion). From a Socratic perspective, Baudrillardian simulation is a contemporary variant of Protagoras’s homo-mensura (discussed in Plato’s Theatetus): “things are largely as we believe them to be” (Chalmers, 2022).

Baudrillard’s notion of comprehensive simulation is, like the Matrix, “founded on information, the model, the cybernetic game—total operationality” (1994 [1981], p. 121). This “total operationality” functions just as efficiently with falsehoods as it does with truths, hence its indifference to classical distinctions. There is, however, a notable difference between Baudrillard’s book and the Matrix film series. The difference pertains to the inside/outside, entrance/exit binaries, as well as the utopian possibility of escape. The Matrix film series involves characters that experience life inside the world of the Matrix plus life outside the Matrix (in the so-called real world). This distinction is explicit, and it is saturated with Hollywood meanings about escape, empowerment, resistance, and revolution. Baudrillard’s book, by contrast, does not offer an obvious, explicit, or utopian exit from simulation.

Baudrillard (1994 [1981], p. 12) cites Disneyland as the “perfect model” of simulation, since it would be foolish to attribute emancipatory meanings to the exit from Disneyland and the subsequent passage to the bare concrete parking lot. The parking lot is not Utopia. Likewise, Baudrillard does not attribute meaning to the exit from Disneyland’s parking lot to the surrounding Los Angeles area. This is not emancipatory, either. This lack of an obvious escape or path of resistance prefigures the recent diminution of confidence in techno-capitalism’s emancipatory projects (Ahlberg et al., 2022; Hietanen et al., 2022).

Simply put, the exit from Disneyland entails a difference in degree, whereas the exit from the Matrix is a difference in kind. When one leaves Disneyland, one departs from an obvious, cartoon-based example of simulation and arrives at a less obvious example of simulation, such as Los Angeles’ shopping malls and Hollywood; but one nonetheless remains in a simulation. In the Matrix film series, by contrast, it is possible to exit the virtual world and return to the real world. This is an ancient, metaphysical, virtual/real distinction—something precluded by Baudrillard’s notion of simulation (1994 [1981]).

Decentraland and other cartoon-based metaverse projects by the Shiba Inu community and the Bored Ape Yacht Club are arguably as “perfect” as Baudrillard’s cartoon-based Disneyland example. Disneyland is restricted to ticket-holders; the “full experience” of the Shiba Inu metaverse or the Bored Ape Yacht Club’s Otherside is restricted to wallet-holders (hence the prompt, “Connect Wallet”). Disneyland accepted its own currency, Disney Dollars, from 1987 onwards; Decentraland, the Shiba Inu community, and the Bored Ape Yacht Club have their own currencies as well. Inside Disneyland, only staff members are allowed to wear copyrighted Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck costumes; Decentraland’s Fashion District sells virtual clothes that can only be worn by token-holders (Goanta, 2020). Disney characters like Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck are intellectual property; therefore, the company decides who has permission to profit from their use. Some Bored Ape characters are, likewise, purchased by companies as tokens and embroiled in intellectual property disputes (Nelson, 2022; Universal Music Group, 2022). Disneyland, finally, involves a “panoply of gadgets” (Baudrillard, 1994 [1981], p. 12); and so, too, do contemporary metaverse projects, from wallets and phantasmagorical goggles to other biometric data-extraction devices (Murphy, 2022). As Baudrillard hinted, one is not emancipated from “the simulation” when one stops playing a character in the Shiba Inu metaverse or when one removes an Oculus headset. One simply moves away from a recent and obvious example of simulation towards a more familiar and subtle example of simulation, like the everyday world of Facebook, Amazon, and other Web 2.0 platforms (Fuchs, 2021; Taplin, 2017; Vaidhyanathan, 2018). One remains in “the simulation”, hooked up to techno-capitalist networks (Morozov, 2019; Sadowski, 2020).

To avoid misunderstandings about simulation and classical representation, Baudrillard explained that a simulation does not involve presentations of original things plus their re-presentations. If a map, for example, re-presents a physical territory, then the map is not a simulation; it is a classical re-presentation. Simulation, by contrast, entails “the generation by models” of an environment that is indifferent to a physical origin or true reality (Baudrillard, 1994 [1981], p. 1); hence, simulated cartoon worlds like the Shiba Inu metaverse and the Bored Ape Yacht Club’s Otherside do not need to re-present physical territories. When Ilyina et al. (2022, p. 117) envisioned the metaverse as “online interaction which practically does not differ from the real-life experience”, this lack of substantial difference accords with Baudrillardian simulation, not classical re-presentation.

Already in the 1980s, Turkle (2009, p. 39) noticed that MIT physicists like William Malven worried about “students substituting models for reality”, students that fully believed in simulations, and students that lost interest in the reality posited by the natural sciences. Over time, as MIT’s engineers and computer scientists migrated to the natural sciences, it became increasingly difficult to delineate the natural sciences and the artificial sciences. The physical and the computer-simulated could both be accepted as scientific (Turkle, 2009). This exemplifies a key point from Baudrillard’s Seduction (1990 [1979])—a book that closely preceded Simulacra and Simulation (1994 [1981]). Baudrillard (1990 [1979], p. 11) asserted that, within a simulated realm, “the very distinction between authenticity and artifice is without foundation. Here, too, one cannot distinguish between reality and its models”. The stage is already set for “the real business of the virtual world” (Elmasry et al., 2022)—the metaverse promised by McKinsey & Company.

Baudrillard’s Seduction (1990 [1979]) aligned simulation with demand, gratification, and transactional certainty. (Seduction, unlike simulation, involves sophisticated desires, irony, secrets, ritual mysteries, and playful anti-gratification.) If transactions and profit-extraction events occur, this is sufficient for a simulated realm, because simulation is conditioned primarily by exchange. Simulation is thus “a monstrous unprincipled enterprise” (Baudrillard, 1994 [1981], pp. 15–22)—a description that is not intended as a moral denunciation or a call for action. As Baudrillard (1994 [1981], pp. 14–15) explained, “indignation, denunciation, etc.” are simply part of the show: these things work “spontaneously for the order of capital” (which is synonymous with simulation). If outrage and “moral panic”, for example, have spectacle-value, then they can sell newspapers and generate numerous other transaction-events. The outrage is not radical or transformative in the critical-interpretivist sense; the status quo is ready and waiting to market it and assimilate it. As Ahlberg et al. (2022, p. 13) put it, “capitalism readily incorporates all criticism directed to it, treating these as sources of incremental innovation to rejuvenate its ever-moving and always-mutable processes of further commodification”. Ethical problems, in short, provide opportunities for marketable solutions.

Simulation is indifferent to classical aesthetics as well. In response to the 1970s’ state-of-the-art, surround sound simulations, Baudrillard doubted the plausibility of metaphysical essences. He instead invoked engineering terms like “technical perfection”, “high fidelity”, “exactitude”, and “synthesis”, as he discussed a simulated environment that seemed “total” and fully rendered (1990 [1979]). Unlike the language of metaphysicians, the 1970s’ engineering terms do not stick out as antiquated or unusual with respect to the contemporary parlance. They are close, for example, to the terms used by Noelle Martin in 2022 to describe Meta’s strategy: “Meta aims to be able to simulate you down to every skin pore, every strand of hair, every micro-movement. The objective is to create 3D replicas of people, places and things, so hyper-realistic and tactile that they’re indistinguishable from what’s real” (Murphy, 2022).

Following Baudrillard, the philosophers Deleuze and Guattari (1994 [1991]) also observed the collapse of physical/metaphysical distinctions. They bitterly proclaimed the triumph of simulation over contemporary philosophies and acknowledged the impotence of principled critique. Deleuze and Guattari (1994 [1991]) credited the invention of simulation to the disciplines of market exchange, namely “computer science, marketing, design, and advertising”. In the era of simulation, a concept (like the metaverse, for example) becomes something that is marketed, events become ticketed (or tokenised), and principled critique is replaced with “sales promotion”. Deleuze and Guattari’s admission of defeat is banal. They depicted their rivals as “inane”. The reigning concept is not special; it may as well be “the simulation of a packet of noodles”. Mastery is reduced to the process of packaging (or, again, tokenising) “the product, commodity, or work of art”. This, in turn, “indicates a society of information services and engineering” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994 [1991], pp. 10–11)—a vision that coincides with Stephenson’s metaverse. As Hietanen et al. (2022, p. 165) recently acknowledged, Deleuze and Guattari foresaw “the emergence of a global capitalist system of deeply abstract financialisation”. So, too, did Baudrillard.

Baudrillard repeatedly returned to simulation’s science-fictional precedents. He named Crash (1973) by J. G. Ballard “the first great novel of the universe of simulation” (1994 [1981], p. 119). The setting of Crash is a human-machine traffic network, imbued with enjoyment/suffering that is equivocal, sexual, and/or fatal. The network from Crash is not the so-called information super-highway (Benjamin & Wigand, 1995); it is an ordinary, concrete highway with cars and amoral collisions. According to Baudrillard’s reading, the network from Crash “does not know dysfunction” (1994 [1981], pp. 118–19). It preempted the Facebook company’s mantra: move fast and break things (Taplin, 2017). Movement, intensity, affects, collision events, and fascination effects achieve prominence; the ethical function/dysfunction distinction is rendered, once again, untenable or insignificant. Even pain and suffering do not function as ethical deterrents; they are rather opportunities. As Ballard (1973, p. 105) put it, the network from Crash issues “units in a new currency of pain and desire”. Ballard (1973) wrote this decades before the arrival of the metaverse’s crypto-currencies (Belk et al., 2022; Gilbert, 2022; Martin et al., 2022)—the so-called “token economy” (Lacity and Treiblmaier, 2022; Sunyaev et al., 2021) or “ludic economy” (Serada et al., 2021)—as well as Palmer Luckey’s fatal NerveGear.

Luckey unveiled the first fatal NerveGear prototype on 6 November 2022. Luckey is the founder of Oculus VR—a company acquired by Facebook, Inc. in 2014 and parodied by HBO’s Silicon Valley in 2017. Luckey described NerveGear as “the incredible device that perfectly recreates reality using a direct neural interface that is also capable of killing the user”, supposedly for fun. The first NerveGear prototype is “just a piece of office art”; but Luckey is confident that “the idea of tying your real life to your virtual avatar” will fascinate others in future, since “the threat of serious consequences can make a game feel real to you and every other person in the game” (2022). This peculiar combination of technological mastery and comic-pathetic degeneracy is true to Stephenson’s Snow Crash (1992), as is the mystery regarding whether NerveGear is intended as earnest or as a joke. NerveGear plays with the equivocality.

2.2 Turkle and Networked Identities

The NerveGear-like notion of human subjects as inseparable from socio-technical networks achieved prominence within STS in the 1980s (Callon, 1986; Latour, 1987). Turkle (1978) arrived at a similar, non-utopian notion in the 1970s via Freud and Lacan. Ballard, likewise, depicted humans stuck in socio-technical networks in his non-utopian science fiction novels from the 1970s. The traffic network from Crash (1973) upholds the name: the effects on its subjects are violent and explicit. Ballard returned to the network entanglement motif in his subsequent novel, High-Rise (1975). He conceived a proto-Thatcherite apartment building as an “attempt to colonise the sky” (p. 19)—a cloud-oriented social network for ambitious professionals and other insubstantial wannabes. “The residents moving along the corridors were the cells in a network of arteries”, Ballard wrote, “the lights in their apartments the neurones of a brain” (p. 40).

Turkle took up a similar, cyborg-like theme of networked identities in 1984. She drew inspiration from a gnomic statement uttered by a thirteen-year-old girl: “There is a little piece of your mind and now it’s a little piece of the computer’s mind”. A second, unnamed individual stated, “I become my computer”. A third fretted, “When my Palm [tablet device] crashed, it was like a death. It had my life on it.... I thought I had lost my mind” (2004 [1984], p. 5). Turkle, as noted, does not conceive technology simply as a useful tool, nor does she focus exclusively on what technology affords its users. She instead highlights the uncanny effects generated by the self-machine bond. This bond did not simply affect how individuals from Turkle’s studies perceived technology; the bond “provoked self-reflection” (2004 [1984], p. 2) and affected how individuals perceived themselves. In other words, technology does not merely facilitate self-expression; it also affects one’s self-impression (Riches et al., 2020; Wiederhold, 2021).

In contrast to Bailenson et al. (2005) and Davis et al. (2009), Turkle does not frame avatar-identities, digital twins, online profiles, or virtual characters as basic re-presentations of “users”. An avatar-identity (or online profile) is a mechanism via which individuals become used by a network (Fuchs, 2021). A so-called user can thus be conceived as something used, manipulated, nudged, and incentivised by a network; and the consequences of this extend to the physical realm. If a user is persecuted or treated like a loser in an online setting, this can affect their identity and self-esteem (Wiederhold, 2021). A virtual realm can even affect the “subjective experience of paranoia” (Riches et al., 2020, p. 337). In a blockchain-specific context, a network’s consequences can include tokenisation or “commoditisation of the self and relationships with others” (Heister and Yuthas, 2020, p. 1). To rehash Baudrillard via Turkle, the distinction between a virtual self and a physical self is trivial. In either case (virtual or physical), the self-identity is networked, it is affected by others, and its putative autonomy is riven with doubts and inconsistency (Ahlberg et al., 2022; Hietanen et al., 2020; Turkle, 2017).

Turkle’s work on networked identities and the self-machine bond was unorthodox in 1984. It followed her book from 1978, dedicated to Freudian institutes in France and Lacan’s unflattering theory of the subject. Instead of treating human subjects as network-independent agents, Turkle held to Lacan’s notion of the ego as impressionable, confused with its surroundings, and normally linked to social networks (les discours). This led her to conceive the self-machine bond as “intimate” (2004 [1984], p. 173).

Turkle’s early work also allowed her to predict the surprising ability of humans to form sentimental ties with virtual companions like Tamagotchis and Pokémon (Paavilainen et al., 2017; Rauschnabel et al., 2017). Campbell (2022) recently issued a prediction based on the same human-machine intimacy. Campbell believes that, within fifty years, the metaverse’s virtual babies will become “indistinct from those in the real world”; hence, she expects some people to cultivate identities as parents in relation to virtual babies. Campbell nicknamed these future babies the Tamagotchi generation.

Companies like Somnium Space are already working to make the Promised Cyberland a Heaven on Earth, so that people can interact with virtual replicas of deceased loved ones. Somnium Space wants to offer humans the ability to cheat death and live vicariously through avatar-identities—impeccably rendered deepfakes. The company named this the “Live Forever” mode (Floridi, 2022)—a new recipe for das Opium des Volkes (Marx, 1844), and a cloud-based Uncanny Valley (Caballar, 2022) that closely approximates “San Junipero” (2016) from the Black Mirror series.

Like Baudrillard, Turkle (2004 [1984]) noticed that the increased sophistication of simulations entailed a decline in critical reflection and knowledge of encoded rules. Successful simulations, like The Sims Online, make it difficult for high school students “to discriminate between the rules of the game and those that operate in a real city”. Even if students can tell the difference, most cannot change the rules, “design or modify the algorithms that underlie the game”. The students are assigned the roles of mere “players” (Turkle, 2004 [1984], p. 13)—or “users”, as they are typically called in the business and engineering literature (Gamble et al., 2016). Role-assigned users are not necessarily empowered (Dotson, 2012); most lack the power “to rewrite the rules”. They are “comfortable as inhabitants of simulated worlds, but most often, they are there as consumers rather than as citizens” (Turkle, 2004 [1984], p. 13).

Turkle’s assertion about role-assigned users as consumers complements Baudrillard’s texts; and like Baudrillard, Turkle witnessed evidence of simulation in the 1970s and 1980s, before its obvious expansion in the twenty-first century (Turkle, 2009). 2022’s metaverse visions, projections, and projects comprise another chapter in this same techno-capitalist narrative.

2.3 Lacan and Capitalist Networks

According to Turkle’s experiences in the 1970s, both Lacan and MIT’s computer scientists “have something to say about the degree to which we are determined by outside forces” (2004 [1984], p. 306). Lacan’s texts from 1970 to 1973 depicted consumers as non-utopian subjects, suggestible choice-makers, or duped actors. Of particular note is a didactic, reduced schema (Fig. 4) that Lacan (1978 [1972]) used to illustrate the consumer’s subjection to capitalist networks.

Lacan’s capitalist schema (Fig. 4) is loosely akin to Greimas’s well-known semiotic square (Wegner, 2009). One could interpret it as a parody of an engineer’s control system diagram (Rosenberg, 2022), since it is especially attuned to dysfunction (Lacan, 1978 [1972]), and its figurative signal flows are erroneous or interrupted (Lacan, 1970, 1973, 1991 [1970]). Lacan’s schema has four terms that occupy four places (Fig. 5).Footnote 6 The four terms are as follows: the subject ($), the object of (dis)satisfaction (a), the order or imperative (S1), and knowledge (S2). (Lacan’s $ sign bears no reference to the dollar.)

Translated descriptions of the four places (Lacan, 1991 [1970])

Lacan’s capitalist schema (Fig. 4) depicts the subject as a consumer-actor (top-left); order—the profit imperative or principle of exchange—occupies the place of belief or truth (bottom-left); productive know-how is put to work (top-right); and finally, the network manufactures a consumable object that is bound together with fleeting satisfaction or abject dissatisfaction (bottom-right). Figure 6 is our annotated version of Lacan’s schema.

Annotated capitalist schema (Lacan, 1978 [1972])

A capitalist network (Fig. 4) is an asocial variation of the four social networks (les quatre discours) that Lacan described from 1969 to 1971 (1970, 1978 [1972], 1991 [1970], 2007 [1971]).Footnote 7 Capitalist networks connect solitary subjects to objects of narcissistic satisfaction that inevitably fall short; hence, they can generate symptoms of discontent (Declercq, 2006; Turkle, 2017; Žižek, 2016). Consider, for example, the Meta Avatars Store (Meta, 2022c). Capitalist networks are transactional, demand-based, and direct rather than amorous, desirous, or mysterious (Lacan, 2011 [1972]); hence, Turkle (2017) believes that contemporary techno-capitalist networks render subjects alone together. More broadly, social media networks are sometimes labelled anti-social and accused of undermining democratic societies (Marantz, 2019; Taplin, 2017; Vaidhyanathan, 2018).

3 Empirical Inquiry

We examined data about the metaverse from 2021 to 2022, sourced from journalistic and social media, the largest self-described metaverse projects listed on the Nasdaq Stock Market and CoinMarketCap, and the United States Patent and Trademark Office. We sourced the journalistic and social media data from BuzzSumo, Reddit, and Twitter. Even though the data sources are contemporary, the findings are relevant to the crypto-financialised metaverse from Stephenson’s Snow Crash (1992). The present findings are also relevant to crypto-asset enthusiasts’ expectations and metaverse developers’ future plans. The recent data therefore contributes to our understanding of the metaverse as split in three: past, present, and future.

BuzzSumo is a commercial, online content database that is often used by media researchers; Reddit is a social discussion website that hosts a Metaverse forum (/r/metaverse, created on 17 August 2008); and Twitter is a popular micro-blogging platform. We used BuzzSumo to track the metaverse keyword’s dissemination via Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Reddit over a thirty-day period (Allcott et al., 2019). We visited Reddit’s Metaverse forum to grasp the frequent discussion topics from 2022 (Amaya et al., 2021). Thanks to MaxQDA 2020’s Import Twitter Data feature, we learnt what hashtags are frequently associated with #metaverse over two seven-day periods (Bruns and Stieglitz, 2013; He, 1999). To better understand the metaverse as technology in the making (Latour, 1987), we also examined eighteen United States patents awarded to Meta Platforms, Inc. in January 2022.Footnote 8

Following the data collection phase, we tabulated three examples of securities and three examples of tokens issued by self-described metaverse developers. We sorted the table according to market capitalisation data sourced from the Nasdaq Stock Market and CoinMarketCap.

The empirical inquiry tests our initial assumption: contemporary, metaverse-related discussions and developments do not seriously challenge theories from the 1970s and 1980s about simulation, networked identities (avatars), and capitalist networks. We also want to find out if social media commentators, journalists, and developers align the metaverse with techno-capitalist networks and crypto-assets or else non-financialised gaming worlds and virtual reality goggles.

3.1 The Metaverse is Techno-capitalist

From a sample of 10,000 English-language tweets (dated 27 May to 3 June 2022), these are the ten most common hashtags that are associated with #metaverse:

-

1.

#NFT

-

2.

#NFTs

-

3.

#crypto

-

4.

#Web3

-

5.

#NFTcommunity

-

6.

#Bitcoin

-

7.

#p2e

-

8.

#BSC

-

9.

#blockchain

-

10.

#DeFi

These ten hashtags help render a vision of the metaverse as crypto-financialised and fixated by proprietorship (Belk et al., 2022; Ryskeldiev et al., 2018; Weking et al., 2023). They point to proprietors of unique assets (#NFT and #NFTs), communities of proprietors (#NFTcommunity), and the Web augmented by blockchain-based property registers and crypto-asset wallets (#Web3, #blockchain, #crypto, and #DeFi). They invoke popular blockchains (#Bitcoin and the Binance Smart Chain, #BSC), and gaming worlds with play-to-earn incentives (#p2e). Note that the top thirty hashtags do not indicate topics like Oculus headsets and virtual reality. The top thirty hashtags only include two game-related hashtags that are not obviously financial: #gaming and #game. The hashtag #gamefi—financialised gaming—is more frequent than both #gaming and #game.

To check these findings, we repeated the #metaverse search and extracted a second sample of 8,319 English-language tweets (dated 24 to 31 October 2022). The ten most common hashtags, once again, emphasise crypto-financial topics rather than virtual reality topics: #NFT, #crypto, #Web3, #NFTs, #blockchain, #bitcoin, #BTC (Bitcoin), #cryptocurrency, #NFTcommunity, and #Binance. Outside the top ten, #VR appears as the twenty-second most common hashtag.

Reddit’s Metaverse community offers further evidence of the crypto-financialised metaverse theme. The community is so accustomed to crypto-asset promotions, their first two rules ban posts that are primarily dedicated to “crypto” as well as posts that serve as advertisements. BuzzSumo’s data highlights the same crypto-financialised theme: as of 4 June 2022, the metaverse article with the highest growth in hits, shares, and links over a thirty-day period is entitled, “The metaverse is money and crypto is king” (Ratan & Meshi, 2022). If BuzzSumo’s list of metaverse-related articles is sorted exclusively by hits (“Total Engagement”), then the top three metaverse articles emphasise Meta’s financial troubles (Dugan, 2022; Hamilton, 2022b) and denigrate virtual reality goggles (Hamilton, 2022a).

3.2 Self-described Metaverse Developers

The crypto-financialised metaverse theme is also evident in recent projects and announcements by self-described metaverse developers. The European Parliamentary Research Service acknowledged the metaverse’s crypto trend in 2022. “Business in the metaverse”, they wrote, “is expected to be underpinned largely by crypto-currencies and non-fungible tokens” (Madiega et al., 2022, p. 1). The crypto trend emerged years after prototypical virtual reality projects or avatars from non-financialised gaming worlds (Takahashi, 2021).

In 2018, Jason Rubin—Head of Content at the Facebook company’s Oculus subsidiary—pitched his vision of the metaverse to the Internet and crypto-asset specialist, Marc Andreessen (Rodriguez, 2021). (Andreessen co-founded the venture capital firm, Andreessen Horowitz.) At the time, Andreessen sat on the Facebook company’s board of directors. Rubin contended that Oculus goggles and non-financialised gaming worlds are not sufficient to capture the interest of mainstream consumers. They only appeal to virtual reality enthusiasts and “hardcore gamers”. He then pitched “THE METAVERSE” as something that goes beyond goggles and gaming—something that consumers “expect and want”. Rubin conceived the metaverse as “a digital universe of virtual ads, filled with virtual goods that people buy” (Rodriguez, 2021). NVIDIA’s CEO, Jensen Huang, shared this same vision of the metaverse: novel crypto-assets plus mainstream-targeted goggles and avatars (Nellis, 2022; Takahashi, 2021).

The Facebook company’s executives were evidently compelled by Rubin’s vision. On 28 October 2021, they renamed the company Meta Platforms, Inc. and prioritised the metaverse (Zuckerberg, 2021). To date, Meta have invested approximately $10 billion in the metaverse (Floridi, 2022). They want “around a billion people in the metaverse doing hundreds of dollars of commerce, each buying digital goods, digital content, different things to express themselves” (Zuckerberg, 2022a). The metaverse envisioned by Meta is evolutionary, which means it is continuous with the Facebook era of social media and targeted advertisements (Clegg, 2022; Meta, 2022a, 2022d). In the first Meta Founder’s letter, Mark Zuckerberg (2021) pitched the metaverse as “the next chapter for the internet”—a chapter that involves digital proprietorship and crypto-assets like “NFT projects”. Zuckerberg (2022b) later announced the development of “a wallet for the metaverse that lets you securely manage your identity, what you own, and how you pay”—a techno-capitalist amalgamation of identity and property (Heister and Yuthas, 2020). This recent wallet announcement follows Calibra and Novi—the Facebook company’s two failed crypto-asset wallet projects from 2019 and 2021 (Pupolizio, 2021).

From mid-2022 onwards, the Meta Avatars Store sold virtual fashion items (Meta, 2022c), and Meta’s Facebook and Instagram platforms supported tradable profile pictures and digital collectibles—so-called non-fungible tokens (NFTs) (Meta, 2022b; Zuckerberg, 2021, 2022b). Other members of the Metaverse Standards Forum, such as NVIDIA and Neal Stephenson’s LAMINA1, announced crypto-asset ventures; but the Forum’s largest member, Microsoft, has not yet finalised a crypto-asset strategy (Nicolle, 2022). Outside the Metaverse Standards Forum, there are smaller, blockchain-based projects like the Bored Ape Yacht Club’s Otherside, the Sandbox, and Decentraland. These three projects attracted attention on the Nasdaq’s website in 2022. They each involve crypto-assets, avatar-identities, and cartoon worlds.

Table 1 presents the three largest metaverse developers from the Nasdaq Stock Market as well as the three largest examples from CoinMarketCap. We sorted the table by the market capitalisation of each security or token on 30 June 2022. The Nasdaq-listed examples are members of the Metaverse Standards Forum (MSF); the CoinMarketCap-listed examples are not. This split already casts doubt on the prospect of globally co-ordinated developers, united in pursuit of an “interoperable” metaverse (Floridi, 2022; Rodriguez, 2021). Table 1 also shows that the capital accrued by the three specialised blockchain projects is not neglible, even though it is less than the capital accumulated by the Big Tech companies.

Unsurprisingly, Microsoft and Meta are the Nasdaq Stock Market’s two largest metaverse developers. Microsoft’s gaming division is “looking into NFTs, crypto-currency and other emerging technologies”; but as of 26 April 2022, Microsoft “don’t yet have anything to share” (Nicolle, 2022). Meta obviously wants to compete with Microsoft and become known as “THE METAVERSE” company (Rodriguez, 2021; Zuckerberg, 2021).

Meta’s vision focuses on targeted advertisements and crypto-asset wallets more than non-financialised gaming worlds (Germain, 2022; Meta, 2022a; Pupolizio, 2021; Zuckerberg, 2022b). On 27 April 2022, Zuckerberg acknowledged that “sometimes people are critical of the ads model”; but Meta does not plan to abandon this model from the Facebook era. On the contrary, Zuckerberg wants employees who are “the people who believe in that [advertisements model] and want to see that continue to grow” (Meta, 2022d). Sir Nick Clegg (Meta’s current President of Global Affairs, and the United Kingdom’s former Deputy Prime Minister) reiterated this point: “For us, the business model in the metaverse is commerce-led. Clearly ads play a part in that” (Murphy, 2022).

In January 2022, Meta successfully patented a broad range of technologies that cover targeted advertisements, simulation, and suggestible subjects (Murphy, 2022). Their newly patented technologies can monitor face and eye movements to determine which advertisements successfully grab and maintain the viewer’s attention; they can curate media content and advertisements based on the viewer’s facial expressions and history of Facebook/Instagram “Likes”; and they can imitate physical bodies’ aesthetic properties and movements to create lifelike avatar-identities. Virtual reality goggles and wearable brain-computer interface systems allow the so-called viewer to become viewed (and better monitored) by the network (Egliston & Carter, 2022a, 2022c). In October 2022, Meta released the Quest Pro headset, which has “cameras that point inward to track your eyes and face” (Germain, 2022). They also issued an “Eye Tracking Privacy Notice” (Meta, 2022a). Meta’s eye tracking “uses cameras to estimate the direction of where your eyes are looking. This feature is used to make your avatar’s eye contact and facial expressions look more natural during your virtual interactions with other users and to improve the image quality within the area where you are looking in VR”.

Big Meta is watching you, closer than ever; but surveillance is not the only eye-catching topic. Even though the Facebook company’s Calibra and Novi wallet projects failed (Pupolizio, 2021), Meta still wants you to hook up a crypto-asset wallet and “express” yourself with NFT profile pictures (Meta, 2022b; Zuckerberg, 2022b; Zuckerberg & Bilyeu, 2022). The crypto-asset wallet developments should not be overlooked.

4 Discussion: A New Orientation for an Old Idea

In response to our conceptual review and empirical findings, we propose a subtle re-orientation—a turn towards the metaverse’s techno-capitalism and crypto-asset wallet-holders, before one discusses virtual worlds and goggle-wearers. Figure 7 presents the re-orientation as a subtle revision of Figure 2 with reversed arrows (Adams, 1994). Recall that Figure 2 presented the academic literature’s default order of priorities, with virtual worlds and goggles first (Narin, 2021). Figure 7 returns the reader to the site of Snow Crash (Stephenson, 1992), yet it also respects contemporary empirical data about crypto-asset wallet-holders. Incidentally, our re-orientation mimicks Jason Rubin’s turn from virtual reality goggles towards crypto-assets and targeted advertisements (Kim, 2021; Kliestik et al., 2022; Rodriguez, 2021). To reiterate, our re-orientation is literally a return, and with respect to the scholarly texts (Narin, 2021), it is also a reversion. This reversion or contrarian mimicry is faithful to the ancient meaning of parody (Janko, 1987).

The metaverse “itself” remains an equivocal knot of techno-capitalism, networked identities, and simulation, not to mention the many “buzzwords and fuzzwords” that are yet to emerge (Cornwall, 2007). We do not untie the metaverse from the past’s science-fictional depictions, the present’s rough implementations, or the future’s Promised Cyberland.

Our conceptual review trivialised the classical, metaphysical distinction between the real and the imaginary (Chalmers, 2022; Rolla et al., 2022). Baudrillard’s theoretical texts (1990 [1979], 1994 [1981]) preempted a common practical consequence of simulation: a resignation of importance attached to the physical/virtual binary (Benjamin, 2018; Turkle, 2009). In response, we did not conduct a detailed investigation of taxonomers’ acronyms: VR (virtual reality), AR (augmented reality), MR (mixed reality), XR (xReality or extended reality), and so on (Milgram & Kishino, 1994; Mystakidis, 2022; Rauschnabel et al., 2022). Baudrillard (1994 [1981]) and Turkle (2004 [1984]) held that simulations and computer-generated worlds are consistent with techno-capitalist culture. They are not radical (in the emancipatory sense) or revolutionary; they are a continuation and an intensification of advertising, marketing, information systems, and consumer-capitalist trends. From 2015 onwards, the same can be said about blockchain tokens, crypto-assets, or simulated capital (Belk et al., 2022; Smith and Burrows, 2021). Blockchain tokenisation is just another process of “economisation” (Çalışkan & Callon, 2009).

In addition to our proposed re-orientation (Fig. 7), we offer two theoretical contributions: a techno-capitalist metaverse schema (Fig. 8) and a sequence of propositions. Our techno-capitalist metaverse schema is an adaptation of Lacan’s capitalist schema (Fig. 4).

Pitched as a sequel to the Facebook era (Zuckerberg, 2021, 2022b), the metaverse connects surveilled wallet-holders (or account-holders) to a plethora of tokenised products. Our metaverse schema thus depicts the wallet-holder ($) as a consumer-subject, a non-utopian choice-maker, or a suggestible wannabe (Dotson, 2012; Sax & Ausloos, 2021). The wallet-holder engages with the metaverse marketplace (S1) to initiate an order.Footnote 9 If the order is registered on a blockchain like Ethereum, then the schema’s bottom-left place entails univocal code—not poetry, mystery, or equivocality—as well as faith-generating properties like verifiability and immutability (De Filippi et al., 2020; Heister & Yuthas, 2020; Pflueger et al., 2022). The principle of exchange, transactional demands, and faith in code are the foundations (S1) of the techno-capitalist network (Becker, 2022).

Knowledge (S2) of a wallet-holder’s history of “Likes” and transactions can be analysed and used for targeted advertisements that influence the wallet-holder’s decisions (Kim, 2021; Kliestik et al., 2022; Murphy, 2022). The network thereby subjects the wallet-holder to persuasive stimuli, much like today’s Web 2.0 platforms (Morozov, 2019; Sadowski, 2020; Zuboff, 2015) but potentially intensified (Rosenberg, 2022). Sophistic knowledge, in short, increases the network’s persuasive power (Fuchs, 2021; Hari, 2022).

The Facebook era already taught us that if an account-holder registers 300 “Likes”, then Big Data knows the account-holder better than his/her spouse does (Youyou et al., 2015). This knowledge can then be used to exacerbate and exploit the subject’s suggestibility (Zuboff, 2015). According to Hietanen et al.(2022, p. 171), personal data collection and surveillance are fundamental to contemporary marketplaces: “marketing now blossoms as surveillance through and through”. Best (2010) also noted an equivalence between surveillance and simulation, back in the Facebook era. Hence, we reiterate our belief that Meta’s vision of the metaverse is continuous with its Facebook-era strategy of targeted advertisements and surveillance. As Fuchs (2019, pp. 58–59) put it, “Big Data capitalism and algorithmic power could result in the world turning into a huge shopping mall in which humans are targeted by ads almost everywhere”—a world ruled by “commercial logic”. Our techno-capitalist metaverse schema (Fig. 8) is appropriate for scenarios like this.

Our schema also illustrates the link between the wallet-holder ($) and his/her desired avatar-identity (a). The latter is a product that must be purchased (or otherwise acquired from the network) and stored in the wallet. The avatar-identity—a virtual self, ego, role, character, or digital twin—is, we repeat, something a wallet-holder has or possesses. The avatar-identity is not a metaphysical soul-substance or a network-independent agent (Lacan, 1975 [1973]; Turkle, 1978); it is a commodity that can be tokenised and traded (Heister and Yuthas, 2020; Muniz & Segall, 2022). Transactions therefore determine what roles a wallet-holder can play or what virtual identities a suggestible wannabe can assume. Transactions also determine what items of tokenised property are associated with a given avatar-identity, such as virtual clothing purchased from the Meta Avatars Store or a showroom in Decentraland’s Fashion District (Goanta, 2020; Meta, 2022c).

We summarise our adapted schema (Fig. 8) below.

-

1.

The consumer-subject ($) chooses what to store in his/her wallet.

-

2.

The choice is registered on a blockchain (or a conventional ledger) as an order. The principle of exchange (S1) is upheld.

-

3.

Orders are aggregated and analysed over time; hence, Big Data (S2) knows how to manipulate, persuade, nudge, incentivise, and suggest.

-

4.

Tokens (a) are issued for a plethora of avatar-identities, tangible and intangible assets, or simulated capital.

-

5.

Acquired tokens (a) are stored in the consumer-subject’s wallet.

-

6.

The consumer-subject ($) becomes a digital proprietor and a suggestible wannabe that is subjected to targeted advertisements.

The consumer-subject ($), at its most basic level, chooses to purchase or not to purchase, to acquire or not to acquire. We should be cautious, however, and not make too much of the consumer-subject’s power of choice (Dotson, 2012; Hietanen et al., 2020). If a consumer-subject chooses to change their avatar-identity’s hair colour (during, for example, a paid visit to a virtual hair-dresser), the choice of colours is not infinite. The possible attributes are encoded by developers and determined by the market. In other words, the consumer-subject from Lacan’s capitalist schema (Fig. 4) and our adapted schema (Fig. 8) should not be confused with power, order, control, rule, law, or imperatives (S1). $ and S1 are separate terms, which means the consumer-subject at best feels empowered or believes herself/himself to be powerful (Ahlberg et al., 2022). As Turkle(2004 [1984], p. 14) stated, “those who write the simulations get to set the parameters”.Footnote 10 The masses of wallet-holders ($) are probably not the ones that encode the rules (S1).

We offer the following sequence of propositions and dialectical reversals as a final theoretical contribution.

-

The metaverse is a techno-capitalist network. This is the most basic interpretation from 1992 to 2022.

-

The metaverse is consistent with the techno-capitalist trends identified by Baudrillard (among others) from 1979 onwards.

-

Meta’s promised future is not a radical departure from the Facebook era. It is a continuation and a potential intensification—“the next chapter for the internet” (Zuckerberg, 2021).

-

The metaverse is associated with crypto-assets, both in 1992 and in 2022.

-

The metaverse’s inhabitants are digital proprietors. They can only assume an avatar-identity if their wallet (or registered account) holds permission. An avatar-identity is therefore something you have, not something you are. It is a product of the network. Turkle’s work is crucial here.

-