Abstract

For conformal maps defined in the unit disk one can define a certain Poisson bracket that involves the harmonic moments of the image domain. When this bracket is applied to the conformal map itself together with its conformally reflected map the result is identically one. This is called the string equation, and it is closely connected to the governing equation, the Polubarinova–Galin equation, for the evolution of a Hele-Shaw blob of a viscous fluid (or, by another name, Laplacian growth). In the present paper we show that the string equation makes sense and holds for general polynomials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper is inspired by 15 years of collaboration with Alexander Vasil’ev. It gives some details related to a talk given at the conference “ICAMI 2017 at San Andrés Island, Colombia”, November 26–December 1, 2017, partly in honor of Alexander Vasilév.

My collaboration with Alexander Vasilév started with some specific questions concerning Hele-Shaw flow and evolved over time into various areas of modern mathematical physics. The governing equation for the Hele-Shaw flow moving boundary problem we were studying is called the Polubarinova–Galin equation, after the two Russian mathematicians Polubarinova-Kochina and Galin who formulated this equation around 1945. Shortly later, in 1948, Vinogradov and Kufarev were able to prove local existence of solutions of the appropriate initial value problem, under the necessary analyticity conditions.

Much later, around 2000, another group of Russian mathematicians, or mathematical physicists, led by Mineev-Weinstein, Wiegmann, Zabrodin, considered the Hele-Shaw problem from the point of view of integrable systems, and the corresponding equation then reappears under the name “string equation”. See for example [11, 12, 14, 25]. The integrable system approach appears as a consequence of the discovery 1972 by Richardson [15] that the Hele-Shaw problem has a complete set of conserved quantities, namely the harmonic moments. See [24] for the history of the Hele-Shaw problem in general. It is not clear whether the name “string equation” really refers to string theory, but it is known that the subject as a whole has connections to, for example, 2D quantum gravity, and hence is at least indirectly related to string theory. In any case, these matters have been a source of inspiration for Alexander Vasilév and myself, and in our first book [8] one of the chapters has the title “Hele-Shaw evolution and strings”.

The string equation is deceptively simple and beautiful. It reads

in terms of a special Poisson bracket referring to harmonic moments and with f any normalized conformal map from some reference domain, in our case the unit disk, to the fluid domain for the Hele-Shaw flow. The main question for this paper now is: if such a beautiful equation as (1) holds for all univalent functions, shouldn’t it also hold for non-univalent functions?

The answer is that the Poisson bracket does not (always) make sense in the non-univalent case, but that one can extend its meaning, actually in several different ways, and after such a step the string equation indeed holds. Thus the problem is not that the string equation is particularly difficult to prove, the problem is that the meaning of the string equation is ambiguous in the non-univalent case. In this paper we focus on polynomial mappings, and show that the string equation has a natural meaning, and holds, in this case. In a companion paper [3] (see also [2]) we treat certain kinds of rational mappings related to quadrature Riemann surfaces.

2 The string equation for univalent conformal maps

We consider analytic functions \(f(\zeta )\) defined in a neighborhood of the closed unit disk and normalized by \(f(0)=0\), \(f'(0)>0\). In addition, we always assume that \(f'\) has no zeros on the unit circle. It will be convenient to write the Taylor expansion around the origin on the form

If f is univalent it maps \({\mathbb D}=\{\zeta \in {\mathbb C}: |\zeta |<1\}\) onto a domain \(\Omega =f({\mathbb D})\). The harmonic moments for this domain are

The integral here can be pulled back to the unit disk and pushed to the boundary there. This gives

where

denotes the holomorphic reflection of f in the unit circle. In the form in (2) the moments make sense also when f is not univalent.

Computing the last integral in (2) by residues gives Richardson’s formula [15] for the moments:

This is a highly nonlinear relationship between the coefficients of f and the moments, and even if f is a polynomial of low degree it is virtually impossible to invert it, to obtain \(a_k=a_k(M_0, M_1, \ldots )\), as would be desirable in many situations. Still there is, quite remarkably, an explicit expressions for the Jacobi determinant of the change \((a_0,a_1,\ldots )\mapsto (M_0,M_1,\ldots )\) when f restricted to the class of polynomials of a fixed degree. This formula, which was proved by to Kuznetsova and Tkachev [13, 21] after an initial conjecture of Ullemar [22], will be discussed in depth below, and it is the major tool for the main result of this paper, Theorem 1.

There are examples of different simply connected domains having the same harmonic moments, see for example [17, 18, 26]. Restricting to domains having analytic boundary the harmonic moments are however sensitive for at least small variations of the domain. This can easily be proved by potential theoretic methods. Indeed, arguing on an intuitive level, an infinitesimal perturbation of the boundary can be represented by a signed measure sitting on the boundary (this measure representing the speed of infinitesimal motion). The logarithmic potential of that measure is a continuous function in the complex plane, and if the harmonic moments were insensitive for the perturbation then the exterior part of this potential would vanish. At the same time the interior potential is a harmonic function, and the only way all these conditions can be satisfied is that the potential vanishes identically, hence also that the measure on the boundary vanishes. On a more rigorous level, in the polynomial case the above mentioned Jacobi determinant is indeed nonzero. Compare also discussions in [16].

The conformal map, with its normalization, is uniquely determined by the image domain \(\Omega \) and, as indicated above, the domain is locally encoded in the sequence the moments \(M_0, M_1, M_2,\ldots \). Thus the harmonic moments can be viewed as local coordinates in the space of univalent functions, and we may write

In particular, the derivatives \({\partial f}/{\partial M_k}\) make sense. Now we are in position to define the Poisson bracket.

Definition 1

For any two functions \(f(\zeta )=f(\zeta ; M_0, M_1, M_2,\ldots )\), \(g(\zeta )=g(\zeta ; M_0, M_1, M_2,\ldots )\) which are analytic in a neighborhood of the unit circle and are parametrized by the moments we define

This is again a function analytic in a neighborhood of the unit circle and parametrized by the moments.

The Schwarz function [1, 20] of an analytic curve \(\Gamma \) is the unique holomorphic function defined in a neighborhood of \(\Gamma \) and satisfying

When \(\Gamma =f(\partial {\mathbb D})\), f analytic in a neighborhood of \(\partial {\mathbb D}\), the defining property of S(z) becomes

holding identically in a neighborhood of the unit circle. Notice that \(f^*\) and S depend on the moments \(M_0, M_1, M_2\ldots \), like f. The string equation asserts that

in a neighborhood of the unit circle, provided f is univalent in a neighborhood of the closed unit disk. This result was first formulated and proved in [25] for the case of conformal maps onto an exterior domain (containing the point of infinity). For conformal maps to bounded domains a proof based on somewhat different ideas and involving explicitly the Schwarz function was given in [5]. For convenience we briefly recall the proof below.

Writing (6) more explicitly as

and using the chain rule when computing \(\frac{\partial f^*}{\partial M_0}\) gives, after simplification,

Next one notices that the harmonic moments are exactly the coefficients in the expansion of a certain Cauchy integral at infinity:

Combining this with the fact that the jump of this Cauchy integral across \(\partial \Omega \) is \(\bar{z}\) it follows that S(z) equals the difference between the analytic continuations of the exterior (\(z\in \Omega ^e\)) and interior (\(z\in \Omega \)) functions defined by the Cauchy integral. Therefore

and so, since \(M_0, M_1,\ldots \) are independent variables,

Inserting this into (8) one finds that \(\{f,f^*\}\) is holomorphic in \({\mathbb D}\). Since the Poisson bracket is invariant under holomorphic reflection in the unit circle it follows that \(\{f,f^*\}\) is holomorphic in the exterior of \({\mathbb D}\) (including the point of infinity) as well, hence it must be constant. And this constant is found to be one, proving (7).

We wish to extend the above to allow non-univalent analytic functions in the string equation. Then the basic ideas in the above proof still work, but what may happen is that f and S are not determined by the moments \(M_0, M_1,\ldots \) alone. Since \(\partial f/\partial M_0\) is a partial derivative one has to specify all other independent variables in order to give a meaning to it. So there may be more variables, say

Then the meaning of the string equation depends on the choice of these extra variables. Natural choices turn out to be locations of branch points, i.e., one takes \(B_j =f(\omega _j)\), where the \(\omega _j\in {\mathbb D}\) denote the zeros of \(f'\) inside \({\mathbb D}\). One good thing with choosing the branch points as additional variables is that keeping these fixed, as is implicit in the notation \(\partial /\partial M_0\), means that f in this case can be viewed as a conformal map into a fixed Riemann surface, which will be a branched covering over the complex plane.

But there are also other possibilities of giving a meaning to the string equation, for example by restricting f to the class of polynomials of a fixed degree, as we shall do in this paper. Then one must allow the branch points to move, so this gives a different meaning to \(\partial /\partial M_0\).

3 Intuition and physical interpretation in the non-univalent case

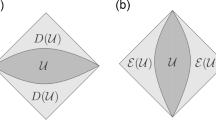

We shall consider also non-univalent analytic functions as conformal maps, then into Riemann surfaces above \({\mathbb C}\). In general these Riemann surfaces will be branched covering surfaces, and the non-univalence is then absorbed in the covering projection. It is easy to understand that such a Riemann surface, or the corresponding conformal map, will in general not be determined by the moments \(M_0, M_1, M_2, \ldots \) alone.

As a simple example, consider an oriented curve \(\Gamma \) in the complex plane encircling the origin twice (say). In terms of the winding number, or index,

this means that \(\nu _\Gamma (0)=2\). Points far away from the origin have index zero, and some other points may have index one (for example). Having only the curve \(\Gamma \) available it is natural to define the harmonic moments for the multiply covered (with multiplicities \(\nu _\Gamma \)) set inside \(\Gamma \) as

It is tempting to think of this integer weighted set as a Riemann surface over (part of) the complex plane. However, without further information this is not possible. Indeed, since some points have index \(\ge 2\) such a covering surface will have to have branch points, and these have to be specified in order to make the set into a Riemann surface. And only after that it is possible to speak about a conformal map f. Thus f is in general not determined by the moments alone. In the simplest non-univalent cases f will be (locally) determined by the harmonic moments together with the location of the branch points.

In principle these branch points can be moved freely within regions a constant values (\(\ge 2\)) of \(\nu _\Gamma \). However, if we restrict f to belong to some restricted class of functions, like polynomials of a fixed degree, it may be that the branch points cannot move that freely. Thus restricting the structure of f can be an alternative to adding new parameters \(B_1, B_2,\ldots \) as in (9). This is a way to understand our main result, Theorem 1 below.

In the following two examples, the first illustrates a completely freely moving branch point, while in the second example the branch point is still free, but moving it forces also the boundary curve \(f(\partial {\mathbb D})\) to move.

Example 1

Let

where \(|a|>1\). This function maps \({\mathbb D}\) onto \({\mathbb D}\) covered twice, so the above index function is \(\nu =2 \chi _{\mathbb D}\). Thus the corresponding moments are

independent of the choice of a, which hence is a free parameter which does not affect the moments. The same is true for the branch point

where

is the zero of \(f'\) in \({\mathbb D}\). Thus this example confirms the above idea that the branch point can be moved freely without this affecting the image curve \(f({\partial {\mathbb D}})\) or the moments, while the conformal map itself does depend on the choice of branch point.

Example 2

A related example is given by

still with \(|a|>1\). The derivative of this function is

which vanishes at \(\zeta =1/\bar{a}\). The branch point is \(B=f(1/\bar{a})=ac/|a|^4\).

Also in this case there is only one nonzero moment, but now for a different reason. What happens in this case is that the zero of \(f'\) in \({\mathbb D}\) coincides with a pole of the holomorphically reflected function \(f^*\), and therefore annihilates that pole in the appropriate residue calculation. (In the previous example the reason was that both poles of \(f^*\) were mapped by f onto the same point, namely the origin.) The calculation goes as follows: for any analytic function g in \({\mathbb D}\), integrable with respect to \(|f'|^2\), we have

where \(A= \bar{a}^2(2|a|^2-1)B^2\). Applied to the moments, i.e. with \(g(\zeta )=f(\zeta )^k\), this gives

Clearly we can vary either a or B freely while keeping \(M_0= \bar{a}^2(2|a|^2-1)B^2\) fixed, so there is again two free real parameters in f for a fixed set of moments.

We remark that this example has been considered in a similar context by Sakai [19], and that \(f'(\zeta )\) is a contractive zero divisor in the sense of Hedenmalm [9, 10]. One way to interpret the example is to say that \(f({\mathbb D})\) represents a Hele-Shaw fluid region caused by a unit source at the origin when this has spread on the Riemann surface of \(\sqrt{z-B}\). See Examples 5.2 and 5.3 in [4].

The physical interpretation of the string equation is most easily explained with reference to general variations of analytic functions in the unit disk. Consider an arbitrary smooth variation \(f(\zeta )=f(\zeta ,t)\), depending on a real parameter t. We always keep the normalization \(f(0,t)=0\), \(f'(0,t)>0\), and f is assumed to be analytic in a full neighborhood of the closed unit disk, with \(f'\ne 0\) on \(\partial {\mathbb D}\). Then one may define a corresponding Poisson bracket written with a subscript t:

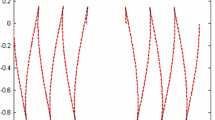

This Poisson bracket is itself an analytic function in a neighborhood of \(\partial {\mathbb D}\). It is determined by its values on \(\partial {\mathbb D}\), where we have

The classical Hele-Shaw flow moving boundary problem, or Laplacian growth, is a particular evolution, characterized (in the univalent case) by the harmonic moments being conserved, except for the first one which increases linearly with time, say as \(M_0= 2t+\mathrm{constant}\). This means that \(\dot{f}=2\partial f/\partial M_0\), which makes \(\{f,f^*\}_t=2\{f,f^*\}\) and identifies the string Eq. (7) with the Polubarinova–Galin equation

for the Hele-Shaw problem.

Dividing (13) by \(|f'|\) gives

Here the left member can be interpreted as the inner product between \(\dot{f}\) and the unit normal vector on \(\partial \Omega =f(\partial {\mathbb D})\), and the right member as the gradient of a suitably normalized Green’s function of \(\Omega =f({\mathbb D})\) with pole at the origin.

Thus (13) says that \(\partial \Omega \) moves in the normal direction with velocity \( |\nabla G_\Omega |\), and for the string equation the interpretation becomes

the subscript “normal” signifying normal component when considered as a vector on \(\partial \Omega \).

The general Poisson bracket (12) enters when differentiating the formula (2) for the moments \(M_k\) with respect to t for a given evolution. For a more general statement in this respect we may replace the function \(f(\zeta )^k\) appearing in (2) by a function \(g(\zeta ,t)\) which is analytic in \(\zeta \) and depends on t in the same way as \(h(f(\zeta ,t))\) does, where h is analytic, for example \(h(z)=z^k\). This means that \(g=g(\zeta ,t)\) has to satisfy

saying that g “flows with” f and locally can be regarded as a time independent function in the image domain of f.

We then have (cf. Lemma 4.1 in [4])

Lemma 1

Assume that \(g(\zeta ,t)\) is analytic in \(\zeta \) in a neighborhood of the closed unit disk and depends smoothly on t in such a way that (14) holds. Then

the last integrand being evaluated at \(\zeta =e^{\mathrm {i}\theta }\).

As a special case, with \(g(\zeta ,t)=h(f(\zeta ,t))\), we have

Corollary 1

If h(z) is analytic in a fixed domain containing the closure of \(f({{\mathbb D}},t)\) then

Proof

The proof of (15) is straight-forward: differentiating under the integral sign and using partial integration we have

which is the desired result. \(\square \)

4 The string equation for polynomials

We now focus on polynomials, of a fixed degree \(n+1\):

The derivative is of degree n, and we denote its coefficients by \(b_j\):

It is obvious from Definition 1 that whenever the Poisson bracket (5) makes sense (i.e., whenever \(\partial f/\partial M_0\) makes sense), it will vanish if \(f'\) has zeros at two points which are reflections of each other with respect to the unit circle. Thus the string equation cannot hold in such cases. The main result, Theorem 1, says that for polynomial maps this is the only exception: the string equation makes sense and holds whenever \(f'\) and \(f'^*\) have no common zeros.

Two polynomials having common zeros is something which can be tested by the classical resultant, which vanishes exactly in this case. Now \(f'^*\) is not really a polynomial, only a rational function, but one may work with the polynomial \(\zeta ^n f'^*(\zeta )\) instead. Alternatively, one may use the meromorphic resultant, which applies to meromorphic functions on a compact Riemann surface, in particular rational functions. Very briefly expressed, the meromorphic resultant \({\mathcal {R}}(g,h)\) between two meromorphic functions g and h is defined as the multiplicative action of one of the functions on the divisor of the other. The second member of (18) below gives an example of the multiplicative action of h on the divisor of g. See [7] for further details.

We shall need the meromorphic resultant only in the case of two rational functions of the form \(g(\zeta )=\sum _{j=0}^n b_j\zeta ^j \) and \(h(\zeta )=\sum _{k=0}^n c_k \zeta ^{-k}\), and in this case it is closely related to the ordinary polynomial resultant \(\mathcal {R}_\mathrm{pol}\) (see [23]) for the two polynomials \(g(\zeta )\) and \(\zeta ^n h(\zeta )\). Indeed, denoting by \(\omega _1,\ldots , \omega _n\) the zeros of g, the divisor of g is the formal sum \(1\cdot (\omega _1)+\dots +1\cdot (\omega _n)-n\cdot (\infty )\), noting that g has a pole of order n at infinity. This gives the meromorphic resultant, and its relation to the polynomial resultant, as

The main result below is an interplay between the Poisson bracket, the resultant and the Jacobi determinant between the moments and the coefficients of f in (16). The theorem is mainly due to Kuznetsova and Tkachev [13, 21], only the statement about the string equation is (possibly) new. One may argue that this string equation can actually be obtained from the string equation for univalent polynomials by “analytic continuation”, but we think that writing down an explicit proof in the non-univalent case really clarifies the nature of the string equation. In particular the proof shows that the string equation is not an entirely trivial identity.

Theorem 1

With f a polynomial as in (16), the identity

holds generally. It follows that the derivative \(\partial f/\partial M_0\) makes sense whenever \(\mathcal {R}(f',f'^*)\ne 0\), and then also the string equation

holds.

Proof

For the first statement we essentially follow the proof given in [6], but add some details which will be necessary for the second statement.\(\square \)

Using Corollary 1 we shall first investigate how the moments change under a general variation of f, i.e., we let \(f(\zeta )=f(\zeta ,t)\) depend smoothly on a real parameter t. Thus \(a_j=a_j(t)\), \(M_k=M_k(t)\), and derivatives with respect to t will often be denoted by a dot. For the Laurent series of any function \(h(\zeta )=\sum _i c_i \zeta ^i\) we denote by \(\mathrm{coeff}_i (h)\) the coefficient of \(\zeta ^i\):

By Corollary 1 we then have, for \(k\ge 0\),

Note that \(f(\zeta )^k\) contains only positive powers of \(\zeta \) and that \(\{f,f^*\}_t\) contains powers with exponents in the interval \(-n\le i\le n\) only.

In view of (16) the matrix

is upper triangular, i.e., \(v_{ki}=0\) for \(0\le i<k\), with diagonal elements being powers of \(a_0\):

Next we shall find the coefficients of the Poisson bracket. These will involve the coefficients \(b_k\) and \(\dot{a}_j\), but also their complex conjugates. For a streamlined treatment it is convenient to introduce coefficients with negative indices to represent the complex conjugated quantities. The same for the moments. Thus we define, for the purpose of this proof and the forthcoming Example 3,

Turning points are the real quantities \(M_0\) and \(a_0=b_0\).

In this notation the expansion of the Poisson bracket becomes

The last summation runs over pairs of indices \((\ell ,j)\) having opposite sign (or at least one of them being zero) and adding up to \(-i\). We presently need only to consider the case \(i\ge 0\). Eliminating \(\ell \) and letting j run over those values for which \(\ell \cdot j\le 0\) we therefore get

Here \(\delta _{ij}\) denotes the Kronecker delta. Setting, for \(i\ge 0\),

we thus have

Turning to the complex conjugated moments we have, with \(k< 0\),

Set, for \(k<0\), \(i\le 0\),

Then \(v_{ki}=0\) when \(k<i\le 0\), and \(v_{kk}=a_0^{-k}\). To achieve the counterpart of (24) we define, for \(i\le 0\),

This gives, with \(i\le 0\),

As a summary we have, from (21), (24) and from the corresponding conjugated equations,

where

We see that the full matrix \(V=(v_{ki})\) is triangular in each of the two blocks along the main diagonal and vanishes completely in the two remaining blocks. Therefore, its determinant is simply the product of the diagonal elements. More precisely this becomes

The matrix \(U=(u_{ij})\) represents the linear dependence of the bracket \(\{f,f^*\}_t\) on \(f'\) and \(f'^*\), and it acts on the column vector with components \(\dot{a}_j\), then representing the linear dependence on \(\dot{f}\) and \(\dot{f}^*\). The computation started at (23) can thus be finalized as

Returning to (25), this equation says that the matrix of partial derivatives \(\partial M_k/ \partial a_j\) equals the matrix product VU, in particular that

The first determinant was already computed above, see (26). It remains to connect \(\det U\) to the meromorphic resultant \(\mathcal {R}(f',f'^*)\).

For any kind of evolution, \(\{f,f^*\}_t\) vanishes whenever \(f'\) and \(f'^*\) have a common zero. The meromorphic resultant \(\mathcal {R} (f', f'^*)\) is a complex number which has the same vanishing properties as \(\{f,f^*\}_t\), and it is in a certain sense minimal with this property. From this one may expect that the determinant of U is simply a multiple of the resultant. Taking homogenieties into account the constant of proportionality should be \(b_0^{2n+1}\), times possibly some numerical factor. The precise formula in fact turns out to be

One way to prove it is to connect U to the Sylvester matrix S associated to the polynomial resultant \(\mathcal {R}_\mathrm{pol}(f'(\zeta ), \zeta ^n f'^*(\zeta ))\). This matrix is of size \(2n\times 2n\). By some operations with rows and columns (the details are given in [6], and will in addition be illustrated in the example below) one finds that

From this (28) follows, using also (18).

Now, the string equation is an assertion about a special evolution. The string equation says that \(\{f,f^*\}_t=1\) for that kind of evolution for which \(\partial /\partial t \) means \(\partial / \partial M_0\), in other words in the case that \(\dot{M}_0=1\) and \(\dot{M}_k=0\) for \(k\ne 0\). By what has already been proved, a unique such evolution exists with f kept on the form (16) as long as \(\mathcal {R} (f',f'^*)\ne 0\).

Inserting \(\dot{M}_k=\delta _{k0}\) in (25) gives

It is easy to see from the structure of the matrix \(V=(v_{ki})\) that the 0:th column of the inverse matrix \(V^{-1}\), which is sorted out when \(V^{-1}\) is applied to the right member in (29), is simply the unit vector with components \(\delta _{k0}\). Therefore (29) is equivalent to

Inserting this into (27) shows that the string equation indeed holds.

Example 3

To illustrate the above proof, and the general theory, we compute everything explicitly when \(n=2\), i.e., with

We shall keep the convention (22) in this example. Thus

for example. When the Eq. (25) is written as a matrix equation it becomes (with zeros represented by blanks)

Denoting the two \(5\times 5\) matrices by V and U respectively it follows that the corresponding Jacobi determinant is

Here U can essentially be identified with the Sylvester matrix for the resultant \( \mathcal {R}(f',f'^*)\). To be precise,

where S is the classical Sylvester matrix associated to the two polynomials \(f'(\zeta )\) and \(\zeta ^2 f'^*(\zeta )\), namely

As promised in the proof above, we shall explain in this example the column operations on U leading from U to S, and thereby proving (32) in the case \(n=2\) (the general case is similar). The matrix U appears in (31). Let \(U_{-2}\), \(U_{-1}\), \(U_{0}\), \(U_1\), \(U_2\) denote the columns of U. We make the following change of \(U_0\):

The first term makes the determinant become half as big as it was before, and the other terms do not affect the determinant at all. The new matrix is the \(5\times 5\) matrix

which has \(b_0\) in the lower left corner, with the complementary \(4\times 4\) block being exactly S above. From this (32) follows.

The string Eq. (20) becomes, in terms of coefficients and with \(\dot{a}_j\) interpreted as \(\partial a_j/\partial M_0\), the linear equation

Indeed, in view of (31) this equation characterizes the \(\dot{a}_i\) as those belonging to an evolution such that \(\dot{M}_0=1\), \(\dot{M}_k=0\) for \(k\ne 0\). As remarked in the step from (29) to (30), the first matrix, V, can actually be removed in this equation.

References

Davis, P.J.: The Schwarz Function and Its Applications. The Mathematical Association of America, Buffalo, NY (1974)

Gustafsson, B.: The string equation for nonunivalent functions. arXiv:1803.02030 (2018a)

Gustafsson, B.: The String Equation for Some Rational Functions. Trends in Mathematics. Birkhäuser, Basel (2018b)

Gustafsson, B., Lin, Y.-L.: Non-univalent solutions of the Polubarinova–Galin equation. arXiv:1411.1909 (2014)

Gustafsson, B., Teoderscu, R., Vasil, A.: Classical and Stochastic Laplacian Growth, Advances in Mathematical Fluid Mechanics. Birkhäuser, Basel (2014)

Gustafsson, B., Tkachev, V.: On the Jacobian of the harmonic moment map. Complex Anal. Oper. Theory 3(2), 399–417 (2009a)

Gustafsson, B., Tkachev, V.G.: The resultant on compact Riemann surfaces. Commun. Math. Phys. 286(1), 313–358 (2009b)

Gustafsson, B., Vasil, A.: Conformal and Potential Analysis in Hele-Shaw Cells. Advances in Mathematical Fluid Mechanics. Birkhäuser, Basel (2006)

Hedenmalm, H., Korenblum, B., Zhu, K.: Theory of Bergman spaces. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 199. Springer, New York (2000)

Hedenmalm, H.: A factorization theorem for square area-integrable analytic functions. J. Reine Angew. Math. 422, 45–68 (1991)

Kostov, I.K. Krichever, I., Mineev-Weinstein, M., Wiegmann, P.B., Zabrodin, A.: The \(\tau \)-function for analytic curves. Random matrix models and their applications, Math. Sci. Res. Inst. Publ., vol. 40, pp. 285–299. Cambridge Univeristy Press, Cambridge (2001)

Krichever, I., Marshakov, A., Zabrodin, A.: Integrable structure of the Dirichlet boundary problem in multiply-connected domains. Commun. Math. Phys. 259(1), 1–44 (2005)

Kuznetsova, O.S., Tkachev, O.S.: Ullemar’s formula for the Jacobian of the complex moment mapping. Complex Var. Theory Appl. 49(1), 55–72 (2004)

Mineev-Weinstein, M., Zabrodin, A.: Whitham-Toda hierarchy in the Laplacian growth problem. J. Nonlinear Math. Phys. 8(suppl), 212–218 (2001)

Richardson, S.: Hele-Shaw flows with a free boundary produced by the injection of fluid into a narrow channel. J. Fluid Mech. 56, 609–618 (1972)

Ross, J., Nyström, D.W.: The Hele-Shaw flow and moduli of holomorphic discs. Compos. Math. 151(12), 2301–2328 (2015)

Sakai, M.: A moment problem on Jordan domains. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 70(1), 35–38 (1978)

Sakai, M.: Domains having null complex moments. Complex Var. Theory Appl. 7(4), 313–319 (1987)

Sakai, M.: Finiteness of the Family of Simply Connected Quadrature Domains. Potential Theory, pp. 295–305. Plenum, New York (1988)

Shapiro, H.S.: The Schwarz Function and Its Generalization to Higher Dimensions, University of Arkansas Lecture Notes in the Mathematical Sciences, 9. Wiley, New York (1992)

Tkachev, V.G.: Ullemar’s formula for the moment map II. Linear Algebra Appl. 404, 380–388 (2005)

Ullemar, C.: Uniqueness theorem for domains satisfying a quadrature identity for analytic functions. Research Bulletin TRITA-MAT-1980-37. Royal Institute of Technology, Department of Mathematics, Stockholm (1980)

van der Waerden, B.L.: Moderne Algebra. Springer, Berlin (1940)

Vasilév, A.: From the Hele-Shaw experiment to integrable systems: a historical overview. Complex Anal. Oper. Theory 3(2), 551–585 (2009)

Wiegmann, P.B., Zabrodin, A.: Conformal maps and integrable hierarchies. Commun. Math. Phys. 213(3), 523–538 (2000)

Zalcman, L.: Some inverse problems of potential theory. Integral Geom 63, 337–350 (1987)

Acknowledgements

The author wants to thank Irina Markina, Olga Vasilieva, Pavel Gumenyuk, Mauricio Godoy Molina, Erlend Grong and several others for generous invitations in connection with the mentioned conference ICAMI 2017, and for warm friendship in general. Some of the main ideas in this paper go back to work by Olga Kuznetsova and Vladimir Tkachev, whom I also thank warmly.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

In Memory of Alexander Vasilév

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gustafsson, B. The string equation for polynomials. Anal.Math.Phys. 8, 637–653 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13324-018-0239-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13324-018-0239-3

Keywords

- String equation

- Poisson bracket

- Polubarinova–Galin equation

- Hele-Shaw flow

- Laplacian growth

- harmonic moment

- resultant