Abstract

Intraperitoneal prophylactic drain (IPD) use in pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is still controversial. A survey was designed to investigate surgeons’ use of IPD in PD patients through 23 questions and one clinical vignette. For the clinical scenario, respondents were asked to report their regret of omission and commission regarding the use of IPD elicited on a scale between 0 (no regret) and 100 (maximum regret). The threshold model and a multilevel mixed regression were applied. One hundred three (97.2%) respondents confirmed using at least two IPDs. The median regret due to the omission of IPD was 84 (67–100, IQR). The median regret due to the commission of IPD was 10 (3.5–20, IQR). The CR-POPF probability threshold at which drainage omission was the less regrettable choice was 3% (1–50, IQR). The threshold was lower for those surgeons who performed minimally invasive PD (P = 0.048), adopted late removal (P = 0.002), perceived FRS able to predict the risk (P = 0.006), and IPD able to avoid relaparotomy P = 0.036). Drain management policies after PD remain heterogeneous among surgeons. The regret model suggested that IPD omission could be performed in low-risk patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) represents the major problem of pancreatic resections, increasing patient morbidity and mortality [1]. For decades, the use of intraperitoneal prophylactic drain (IPD) has been considered by pancreatic surgeons as one of the most important strategies to mitigate the negative effect of clinically relevant POPF (CR-POPF) [2]. The IPD could allow early recognition of POPF and POPF-related complications [3], such as post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH) [4]. Moreover, IPD could mitigate the negative consequences of CR-POPF by evacuating pancreatic, biliary, enteric juice, and blood from the peritoneal cavity early [3]. However, several issues about IPD use and management remain under debate. Indeed, the dogma of routine IPD use was challenged, especially in low-risk pancreatic remnants, and several randomized studies reported similar complication rates when IPD was omitted [5,6,7,8]. Second, the timing of removal was recently investigated, hypothesizing that early removal could be safe [9,10,11,12,13]. Third, the use of active suction was recently investigated, suggesting that the type of drainage system does not influence the development of POPF [14]. Despite the availability of high-quality evidence, the use and management of IPD drain remain heterogeneous, even in high-volume centers [15]. Indeed, it seems that the adoption of modern drain policies, such as IPD omission or early removal, has been very slow by pancreatic surgeons despite the results of RCTs [15]. The present survey was designed to investigate the attitude of pancreatic surgeons in the Italian community toward the use of IPD. Additionally, the regret-based decision model was applied. Regret models were beneficial when medical choices could produce uncertain outcomes. Using the physician's emotional intelligence (“anticipated regret”) elicited by one or more clinical scenarios, it is possible to optimize decision-making by adopting the therapeutic strategy, which implies lesser regret in case of a wrong choice.

Materials and methods

Survey

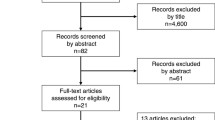

An online survey designed using the online platform Survey Planet® was sent in June 2022 to the Italian community of pancreatic surgeons. Particularly, surgeons affiliated with the Italian Association for the Study of the Pancreas (AISP) and the Italian Association of Hepato-biliary-pancreatic Surgery (AICEP) were contacted. A link to the survey was forwarded using the official email address, the official Twitter and Facebook accounts of AISP, and the official WhatsApp channel of AICEP.

The survey was anonymous, but participants were asked to send an e-mail confirming their participation. All responses were mandatory, and each answer could not be subsequently modified to avoid bias. A selected panel of expert pancreatic surgeons from the Surgical Taskforce of Italian Association for the Study of the Pancreas prepared 23 queries about the use of drainage in PD: 14 multiple choice, 4 visual analog scales, and three open questions (Supplementary file). We collected general information about the participants (gender, age) and their professional level (resident, fellow, or expert surgeon). Also, information about the clinical practice setting was collected: country, institutional volume of pancreatic resection, and, if present, other types of institutional surgical activities (colorectal resection, liver resection, upper gastro-intestinal, or others). Subsequently, we asked the following questions: (i) routine use of Fistula Risk Score (FRS) according to Callery [15]; (ii) number and type of drains used; (iii) timing and indications for drain removal; and iv) motivations behind individual choices using a visual analogue scale (0–10). The study followed the COREQ standards for reporting qualitative research [16]. Ethical approval was not sought for the present study because of its survey nature.

Regret model

At the end of the survey, a clinical hypothetical vignette was presented to participants to measure their regret when choosing drain placement. The clinical case included a 67-year-old patient with pancreatic head adenocarcinoma, in excellent general conditions, who underwent standard PD with firm pancreatic stump and dilated main pancreatic duct (> 5 mm); intraoperative blood loss was between 400 and 700 mL. The Trudeau catalog [17] (scenario two) was used to relate the FRS (in this case, equal to 1 point) with the CR-POPF risk of 3.6%.

Based on their knowledge, experience, and preference, pancreatic surgeons were asked to elicit their personal regret due to the loss of opportunity of CR-POPF mitigation if the drain was not placed, as well as the regret following the placement of a useless IPD. Thus, the regret of omission was here represented by the regret felt by the surgeon who omitted the IPD in a patient who otherwise may have benefited from the drainage in case of CR-POPF occurrence. On the other hand, the regret of the commission referred to the regret felt by the surgeon who decided to place an IPD, resulting in useless action because the patients did not develop CR-POPF.

The regret of omission was measured through the following question: “How would you rate the level of your regret, on a scale of 0 to 100 (0 = no regret, 100 = maximum regret) if you decided NOT to place an intraperitoneal prophylactic drain and the patient developed after PD a clinically relevant POPF requiring CT-percutaneous drainage?”. Regret of the commission was elicited as follows: “How would you rate the level of your regret, on a scale of 0 to 100 (0 = no regret, 100 = maximum regret) if you decided to place an intraperitoneal prophylactic drain after PD, and the patient experienced regular postoperative course without clinically relevant POPF?”.

In the regret model, Mt represents the POPF threshold at which regret of omission equals the regret of commission: Mt = (1 / [1 + (regret of omission/regret of commission)]) × 100 [18]. In other words, Mt is the probability of clinically relevant POPF at which we are indifferent between two management strategies. If the expected CR-POPF rate is above the threshold, the regret of not placing IPD (omission) will be larger than the regret of placing them (commission). Hence, we should place IPD to minimize regret.

Statistical analysis

Frequencies and percentages were used to describe categorical data. For continuous measures, mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile (IQR) ranges were used for continuous values. Age, gender, professional level, hospital type, the main activity of the surgical unit, implementation of minimally-invasive PD (MIPD), type and number of drainage, FRS use, the timing for drain removal, tailored strategy for the low and high-risk pancreatic remnant, perceived importance of FRS, closed system, drain mobilization, drain placement in preventing POPF grade B and C were tested in predicting regret of omission, commission and CR-POPF threshold. For these analyses, multilevel multivariate mixed-effects models were used. In these models, the geographic area of the participants was considered fixed because the study was not interested in regional differences. In other words, the total regression line represents the average Italian centers, independently from geographic origin. The effect of covariates was measured, reporting the coefficient and SE. Post-estimation mean regrets and threshold were calculated for each category. A P value < 0.05 indicates a non-negligible effect on the regrets or threshold. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata (Stata Statistical Software: Release 15, StataCorp, LLC, College Station, TX).

Results

Participants

The survey was released on July 08, 2022, and was closed on August 31, 2022. One hundred six surgeons completed the online questionnaire. At the time of the survey, 143 surgeons were registered in AISP and AICEP. The engagement rate was 74.1%. In Table 1, the general information of respondents is shown. The median age of respondents was 46 years (36–57). 88.7% of respondents were attending surgeons, while 11.3% were residents or fellows. Most surgeons (71.7%) worked in hospitals located in Northern Italy (Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, Veneto, Piedmont Trentino South-Tyrol, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, and Liguria). The remaining 33% were located in Central (Lazio, Tuscany, and Marche) or Southern Italy (Puglia, Campania, Abruzzi, Basilicata, Calabria, and Sicily) of Italy. Most worked in public academic (51.9%) or non-academic (23.6%) hospitals. The remaining 26 participants worked in private academic (17.9%) or private non-academic (6.6%) hospitals. Most participants (66%) worked in high-volume (> 30 pancreatic resections yearly) centers, while 24.5% and 17.9% were in medium and low-volume hospitals, respectively. Regarding the main surgical activity of their division, 35.9% answered hepato-biliary, 30.2% answered pancreatic, and 5.7% answered colorectal resections. Only 28.3% declared to work in a division where all sub-specialties mentioned above were equally represented. Only 33.9% of surgeons declared to perform MIPD.

Use and management of drainage

The use and management of drains are reported in Table 2. Most surgeons (49.1%) declared using an Easy Flow or Penrose-type passive drain. The second most used drainage (33%) was a closed system (Jackson-Pratt or Blake drainage) with or without active suction. Robison drainage (i.e., silicone round drain with closed system) was used only by 15.1% of participants. Almost all respondents place two or more drains (97.2%) after PD. Only 24.5% of surgeons remove the IPD within the third POD despite the criteria for early removal being satisfied. Two-thirds of the respondents (66%) routinely use FRS. The median perceived importance of FRS in predicting CR-POPF was 2 (0–6, IQR); the median perceived importance of a closed system in predicting CR-POPF grade B was 3 (0–5, IQR); the perceived importance of drain mobilization in mitigating CR-POPF grade B was 5 (2–7, IQR); the perceived importance of drain in preventing CR-POPF grade C was 6 (3–8, IQR).

A change of strategy in low-risk pancreatic stumps was declared by 14.2% of respondents, reducing the number of drains (5.6%) or not placing any (4.7%). A change of strategy in high-risk pancreatic remnants was declared by 18.9% of respondents, increasing the number of drains (10.4%), changing the type (4.7%), or both (3.8%).

Regret analysis

Regret of omission, commission, and thresholds are reported in Fig. 1. The mean regret of omission was 73 (± 31, SD), with a median of 80 (60–100, IQR). The mean regret of the commission was 10 (± 16.8, SD) with a median of 1 (1–10). The mean CR-POPF risk probability threshold at which drainage omission was the less regrettable choice was consequently 12(± 18) % with a median of 3% (1–18%, IQR). In Fig. 2, we reported the percentage of responders who perceived IPD omission as the least regrettable choice for each value of FRS and related probability of CR-POPF.

Percentage of responders who consider the IPD omission as the least regrettable choice based on the risk of CR-POPF. The x-axis represents the Fistula Risk Score categories (FRS); the blue line reports the risk of CR-POPF related to each category of FRS according to Trudeau et al. [22]; the orange line reports the percentage of responders who perceived the IPD omission as the least regrettable choice for the related risk of CR-POPF

Multilevel effect multivariate regressions are reported in Supplementary Table 1, while the estimated mean of regrets and threshold was reported in Table 3. Age, gender, professional level, hospital type, active suction preference, custom to change strategy based on the risk, and perceived importance of drain mobilization did not affect regrets and threshold for CR-POPF. Responders working in high-volume hospitals had significantly lower mean regret of omission than those working in low-volume hospitals (77 ± 19 vs. 71 ± 18; P < 0.001).

Compared with colorectal surgeons, participants who work in a specialized pancreas unit had an increased mean regret of omission (72 ± 19 vs. 68 ± 21; P = 0.021). However, mean regrets of commission and the final threshold for CR-POPF remain unaffected by the prominent activity of the surgical unit. Comparing MIPD and non-MIPD surgeons, the mean final threshold for CR-POPF was 13 ± 7% vs. 12 ± 7% (P = 0.048), respectively. Surgeons who preferred Easy Flow or Penrose drains (7 ± 6) had a significantly lower (P < 0.001) mean regret of commission than those who preferred Robinson, Jackson-Pratt, or Blake (12 ± 8) drains. Participants who used a closed system had higher threshold for CR-POPF than those adopted open systems (15 ± 6% vs. 11 ± 7; P = 0.004). Obviously, the answerer who used more than two drains after PD experienced a higher regret of omission than those who placed only one or two drains (90 ± 13 vs. 67 ± 16; P = 0.004). The survey participants who used the FRS score had a lower mean regret of omission than those who did not use this prediction system (88 ± 11 vs. 66 ± 17; P = 0.001). The responders who routinely removed the drain within POD 3 had a superior mean threshold (12 ± 7 vs. 15 ± 9; P = 0.002). The higher the perceived importance of FRS in predicting CR-POPF, the lower the regret of omission (P ≤ 0.001) and CR-POPF threshold (1.1 ± 0.4; P = 0.006). On the contrary, increasing the perceived importance of FRS, the regret of the commission was slightly higher (P = 0.011). The perceived importance of the closed system in preventing Grade B CR-POPF slightly influenced the regret of the commission (P < 0.001) but not the regret of omission and CR-POPF threshold. The perceived importance of drain placement in preventing Grade C CR-POPF influenced both regrets and threshold: the higher the perceived importance, the higher the regret of omission (P < 0.001); the higher the perceived importance, the lower the regrets of commission (P < 0.001) and CR-POPF threshold (P = 0.036).

Discussion

The present survey demonstrated that Italian pancreatic surgeons routinely use IPD after PD, as 98% of participants declared placing two or more drains at the end of surgery. Only a minority of interviewed surgeons reported a change in perioperative drain strategy based on the intraoperative characteristics of the pancreatic remnant and the relative pancreatic fistula risk score, suggesting a preference for a standard and consistent drain policy rather than a selective POPF mitigation strategy. In addition, our work highlighted the large heterogeneity in drain type preference and postoperative drain management among the Italian community of pancreatic surgeons.

This survey outlines a “real-life” scenario in which the IPD is deemed as a necessary tool for safely monitoring and managing the postoperative course after PD. This attitude is confirmed by the reluctance to remove the IPD early, even when patients were clinically well, drain fluid amylase concentration was low, and the quality of the fluid was not suspicious. Indeed, only one out of four survey participants adopts an early drain removal policy in their practice. Surprisingly, more than 30% of surgeons remove the IPD very late, after POD5, even when the postoperative course was uneventful. These data are in contrast with the available evidence. In fact, a recent meta-analysis of RCTs showed that IPD omission after pancreatic resection is a safe alternative to their routine use in low-risk scenarios [2]. Moreover, at least five recent RCTs [9,10,11,12,13] supported adopting early removal in patients with low risk for CR-POPF and regular postoperative stay. Indeed, in recent recommendations from the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society for patients undergoing PD, the level of evidence in favor of selective IPD omission and early removal was moderate and high, respectively [19]. It may appear surprising that one of the cornerstones of the ERAS philosophy finds a high resistance in the pancreatic surgeon community. Still, it is no secret that surgical traditions are the most challenging to abandon.

The present survey suggested that the dogma of mandatory drainage persists, confirming the results of a previous survey by Pergolini et al. [20], including 42 expert pancreatic surgeons. However, in our survey, we also investigated the reasons for resistance to selective IPD omission using the “regret theory” approach. The regret methodology gives a scientific value to emotional intelligence: a physician making a nonrepeatable decision under uncertainty (e.g., omission or not of therapy) could experience regret in case of a negative result. This regret can be measured and used to optimize the choices [21]. Measuring the regret of omission and commission in a prespecified scenario allows us to calculate the acceptable probability threshold for a negative event, at which the omission of therapy is the least regrettable choice.

In the current survey, we asked participants to anticipate the regret, using a clinical case of a patient undergoing PD with an expected low risk of CR-POPF. By asking the responders to elicit both regrets (commission and omission) in a real-life scenario, we captured all different shades of the emotional intelligence of interviewed surgeons without imposing pre-concepts about the drain-less policy. Moreover, a low-risk scenario was chosen in intermediate and high-risk scenarios of CR-POPF; the omission of drainage is generally not accepted by pancreatic surgeons. For this reason, the drain-less approach could not reflect a real-life problem when the risk of CR-POPF is not low.

As expected, the median regret of omission was very high, while the regret of the commission was very low, confirming the pancreatic surgeons' unwillingness to accept the selective IPD omission. The median value of CR-POPF risk probability, at which the least regrettable choice was the IPD omission, was 3%. This result may appear to strengthen IPD omissions as a definitive choice in low-risk scenarios. Using the FRS catalog of Trudeau et al. [16] that reported granular data about FRS scenarios occurrence and CR-POPF risk, it is possible to estimate how many patients could be managed without drainage based on the emotional intelligence of pancreatic surgeons. In fact, it is surprising that nearly 15% of patients who underwent PD could have a risk of CR-POPF equal to or inferior to 3%. For this reason, based on regret theory, nearly one patient out of six/seven could be managed with selective IPD omission despite worldwide reluctance. We observed some interesting findings by analyzing factors related to the CR-POPF threshold and regrets. Regret of omission was reduced in centers at high volume for pancreatic surgery (> 30 pancreatic resections/year). Surgeons who work in high-volume hospitals can rely on key expertise and resources, such as interventional radiology [22] and operative endoscopy [23], that can manage peri-anastomotic fluid collections and other life-threatening complications related to POPF (i.e., post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage). At the same time, dedicated pancreatic surgeons perceived and feared, more than other surgeons, the devastating potential effects of undrained CR-POPF. Interestingly, the regret of omission was reduced in those surgeons who looked at FRS as trustworthy in predicting CR-POPF. Thus, in the presence of a well-established and valid tool to anticipate CR-POPF risk, the attitude of surgeons in adopting selective IPD omission is enhanced. In other words, the reluctance to adopt IPD omission seems more related to the lack of confidence in the risk score system to predict the CR-POPF risk than to an absolute refusal of this strategy. Indeed, when surgeons were more confident using FRS, the IPD omission represented the least regrettable choice for CR-POPF probability higher than 3%. However, the problem seems to be the overall low confidence in FRS’s ability. In fact, the median perceived importance is very low (2 out of 10 on the VAS scale) despite the amount of literature available in favor of this score [15, 16]. Also, the role of IPD in preventing reintervention is generally overestimated, and the higher the perceived importance of drainage in preventing grade C CR-POPF, the higher the regret of omission. In fact, the CR-POPF threshold, at which IPD omission is the least regrettable choice, was lower than 3% for the surgeons who overestimated the role of IPD in preventing reintervention. An interesting finding is that minimally invasive PD surgeons have a shallow CR-POPF threshold. In other words, pancreatic surgeons perceive the minimally invasive approach as a procedure more at risk for CR-POPF than open. For this reason, selective IPD omission is often considered a regrettable strategy in very low-risk scenarios. In contrast, surgeons who used a closed drain system seem to adopt IPD omission also in settings with a higher risk of CR-POPF (more than 3%). This may be explained by the theory of retrograde infection supported by those pancreatic surgeons using the closed system; in the event of a small biochemical leak, the presence and persistence of a peripancreatic drain could increase the fistula output and facilitate a retrograde infection, converting it into a CR-POPF [24, 25]. However, a recent non-inferiority trial has demonstrated that more than 60% of bacteria contaminating the drainage fluid after PD were attributable to human gut flora rather than external bacteria [2].

The current study has some limitations. First, the group of survey participants was very heterogeneous, including surgeons performing pancreatic resections in low and high-volume settings in academic and non-academic institutions. Nonetheless, the survey is a snapshot of “real-life” clinical practice in Italian hospitals. Second, each respondent declared their habits based on personal and center experience, which did not necessarily reflect adequate and updated knowledge of the literature available. The third limitation is represented by the fact that we assumed that a single decision-maker is involved in the IPD omission or commission.

In conclusion, this survey demonstrated that, despite the availability of several RCTs and metanalysis about IPD use after PD, a certain reluctance from pancreatic surgeons to abandon the dogmas exists. This reluctance appears related to multiple factors: (i) the shortcomings of available risk prediction tools for CR-POPF; (ii) the uncertainty of outcomes from a minimally invasive approach in PD; (iii) the concern about an increase in the re-laparotomy rate. Generally, an interesting observation was that, despite the amount of literature available encouraging early removal [5] or drainage omission [8] in low-risk patients, the customs of Italian pancreatic surgeons remain very conservative. Nonetheless, evaluating emotional intelligence, which depends on experience and knowledge, can help surgeons understand that selective IPD omission could be the least regrettable choice when the risk of CR-POPF is low. Considering this, it seems very important an educational process to ameliorate the adoption of a tailored drain policy risk based in patients who underwent PD. On the other hand, it is important to underline that patients with intermediate or high risk of CR-POPF largely benefit from drain placement [28]. Further studies are required to achieve progress in solving this issue.

Data Availability

The data of the survey were available, on request.

References

Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M, Allen P, Andersson R, Asbun HJ, Besselink MG, Conlon K, Del Chiaro M, Falconi M, Fernandez-Cruz L, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Fingerhut A, Friess H, Gouma DJ, Hackert T, Izbicki J, Lillemoe KD, Neoptolemos JP, Olah A, Schulick R, Shrikhande SV, Takada T, Takaori K, Traverso W, Vollmer CR, Wolfgang CL, Yeo CJ, Salvia R, Buchler M, International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) (2017) The 2016 update of the international study group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery 161(3):584–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.014

Hüttner FJ, Probst P, Knebel P et al (2017) Meta-analysis of prophylactic abdominal drainage in pancreatic surgery. Br J Surg 104:660–668

van Santvoort HC (2023) Postoperative pancreatic fistula: focus should be shifted from early drain removal to early management. BJS Open 6(7):zrac156

Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C et al (2007) Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an international study group of pancreatic surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery 142:20–25

Ricci C, Grego DG, Alberici L et al (2024) Early versus late drainage removal in patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials using trial sequential analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 31:2943–2950

Conlon KC, Labow D, Leung D et al (2001) Prospective randomized clinical trial of the value of intraperitoneal drainage after pancreatic resection. Ann Surg 234:487–493

Van Buren G, Bloomston M, Hughes SJ et al (2014) A randomized prospective multicenter trial of pancreaticoduodenectomy with and without routine intraperitoneal drainage. Ann Surg 259:605–612

Witzigmann H, Diener MK, Kienkötter S et al (2016) No need for routine drainage after pancreatic head resection: the dual-center, randomized, controlled PANDRA trial (ISRCTN04937707). Ann Surg 264:528–537

Bassi C, Molinari E, Malleo G et al (2010) Early versus late drain removal after standard pancreatic resections: results of a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg 252:207–214

McMillan MT, Malleo G, Bassi C et al (2015) Drain management after pancreatoduodenectomy: reappraisal of a prospective randomized trial using risk stratification. J Am Coll Surg 221(4):798–809

Dembinski J, Mariette C, Tuech JJ et al (2019) Early removal of intraperitoneal drainage after pancreatoduodenectomy in patients without postoperative fistula at POD3: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Visc Surg 156(2):103–112

Dai M, Liu Q, Xing C et al (2020) Early drain removal after major pancreatectomy reduces postoperative complications: a single-center, randomized, controlled trial. J Pancreatol 3:2

Dai M, Liu Q, Xing C et al (2022) Early drain removal is safe in patients with low or intermediate risk of pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a multicentre: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 275:e307–e314

Park LJ, Baker L, Smith H, Lemke M, Davis A, Abou-Khalil J, Martel G, Balaa FK, Bertens KA (2021) Passive versus active intra-abdominal drainage following pancreatic resection: does a superior drainage system exist? A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg 45(9):2895–2910. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-021-06158-5

Callery MP, Pratt WB, Kent TS, Chaikof EL, Vollmer CM Jr (2013) A prospectively validated clinical risk score accurately predicts pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg 216(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.09.002

Trudeau MT, Casciani F, Ecker BL, Maggino L, Seykora TF, Puri P, McMillan MT, Miller B, Pratt WB, Asbun HJ, Ball CG, Bassi C, Behrman SW, Berger AC, Bloomston MP, Callery MP, Castillo CF, Christein JD, Dillhoff ME, Dickson EJ, Dixon E, Fisher WE, House MG, Hughes SJ, Kent TS, Malleo G, Salem RR, Wolfgang CL, Zureikat AH, Vollmer CM, on the behalf of the Pancreas Fistula Study Group (2022) The fistula risk score catalog: toward precision medicine for pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 275(2):e463–e472

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19(6):349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Pauker SG, Kassirer JP (1980) The threshold approach to clinical decision making. N Engl J Med 302:1109–1117

Melloul E, Lassen K, Roulin D, Grass F, Perinel J, Adham M, Wellge EB, Kunzler F, Besselink MG, Asbun H, Scott MJ, Dejong CHC, Vrochides D, Aloia T, Izbicki JR, Demartines N (2020) Guidelines for perioperative care for pancreatoduodenectomy: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) recommendations 2019. World J Surg 44(7):2056–2084

Pergolini I, Schorn S, Goess R, Novotny AR, Ceyhan GO, Friess H, International Pancreatic Surgery Centers, Demir IE (2022) Drain use in pancreatic surgery: Results from an international survey among experts in the field. Surgery 172(1):265–272

Djulbegovic B, Hozo I, Schwartz A, McMasters KM (1999) Acceptable regret in medical decision making. Med Hypotheses 53(3):253–259

Cucchetti A, Djulbegovic B, Crippa S, Hozo I, Sbrancia M, Tsalatsanis A, Binda C, Fabbri C, Salvia R, Falconi M, Ercolani G, Reg-PanC study group (2023) Regret affects the choice between neoadjuvant therapy and upfront surgery for potentially resectable pancreatic cancer. Surgery 173(6):1421–1427

Sanjay P, Kellner M, Tait IS (2012) The role of interventional radiology in the management of surgical complications after pancreatoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford) 14(12):812–817

Woo DH, Lee JH, Park YJ, Lee WH, Song KB, Hwang DW, Kim SC (2022) Comparison of endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage and percutaneous catheter drainage of postoperative fluid collection after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 26(4):355–362

Kawai M, Tani M, Terasawa H et al (2006) Early removal of prophylactic drains reduces the risk of intra-abdominal infections in patients with pancreatic head resection: prospective study for 104 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 244:1–7

Hu Y, Zhao Y-P, Liao Q et al (2008) Relationship between the pancreatic fistulae and the bacterial culture of abdominal draining fluid after pancreatic operations. Chin J Pract Surg 1:53–55

Marchegiani G, Perri G, Pulvirenti A, Sereni E, Azzini AM, Malleo G, Salvia R, Bassi C (2018) Non-inferiority of open passive drains compared with closed suction drains in pancreatic surgery outcomes: a prospective observational study. Surgery 164(3):443–449

Chang JH, Stackhouse K, Dahdaleh F, Hossain MS, Naples R, Wehrle C, Augustin T, Simon R, Joyce D, Walsh RM, Naffouje S (2023) Postoperative day 1 drain amylase after pancreatoduodenectomy: optimal level to predict pancreatic fistula. J Gastrointest Surg 27(11):2676–2683

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The survey was conducted with the endorsement of the Italian Association for the Study of the Pancreas (AISP) and in collaboration with the Italian Association of Hepato-biliary-pancreatic Surgery (AICEP). Study group for pancreatic drainages utilization (Pan-Drain), collaborators: Laura Alberici, Francesca Aleotti, Sergio Alfieri, Marco Angrisani, Alessandro Anselmo, Elisa Bannone, Matteo Barabino, Giulio Belfiori, Andrea Belli, Giulio Belli, Chiara Bonatti, Gianluca Borgia, Lucio Caccamo, Donata Campra, Damiano Caputo, Riccardo Casadei, Matteo Cescon, Davide Citterio, Ettore Colangelo, Michele Colledan, Roberto Coppola, Stefano Crippa, Tommaso Dall'Olio, Luciano De Carlis, Donato De Giorgi, Raffaele De Luca, Antonella Del Vecchio, Raffaele Della Valle, Fabrizio Di Benedetto, Armando Di Dato, Stefano Di Domenico, Giovanni Di Meo, Pierluigi Di Sebastiano, Maria Ettorre Giuseppe, Alessandro Fogliati, Antonio Frena, Francesco Gavazzi, Batignani Giacomo, Luca Giannotti, Felice Giuliante, Gianluca Grazi, Tommaso Grottola, Salvatore Gruttadauria, Carlo Ingaldi, Frigerio Isabella, Francesco Izzo, Giuliano La Barba, Serena Langella, Gabriella Lionetto, Raffaele Lombardi, Lorenzo Maganuco, Laura Maggino, Giuseppe Malleo, Lorenzo Manzini, Giovanni Marchegiani, Alessio Marchetti, Stefano Marcucci, Marco Massani, Laura Mastrangelo, Vincenzo Mazzaferro, Michele Mazzola, Riccardo Memeo, Caterina Milanetto Anna, Federico Mocchegiani, Luca Moraldi, Francesco Moro, Niccolò Napoli, Gennaro Nappo, Bruno Nardo, Alberto Pacilio Carlo, Salvatore Paiella, Davide Papis, Alberto Patriti, Damiano Patrono, Enrico Prosperi, Silvana Puglisi, Marco Ramera, Matteo Ravaioli, Aldo Rocca, Andrea Ruzzente, Luca Sacco, Grazia Scialantrone, Matteo Serenari, Domenico Tamburrino, Bruna Tatani, Roberto Troisi, Luigi Veneroni, Marco Vivarelli, Matteo Zanello, Giacomo Zanus, Costanza Zingaretti Caterina, Andrea Zironda.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Alma Mater Studiorum - Università di Bologna within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Ricci Claudio: study planning, first draft manuscript, formal analysis. Nicolò Pecorelli: study planning, first draft manuscript. Alessandro Esposito: study planning, collect the data. Stefano Partelli: study planning, collect the data. Giovanni Capretti: study planning, collect the data. Giovanni Butturini: study planning, collect the data, formal analysis. Ugo Boggi: study planning, manuscript revision. Alessandro Zerbi: manuscript revision. Roberto Salvia: manuscript revision & approval. Massimo Falconi: manuscript revision & approval. Pan-drain study groups: collaborators in the survey.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest or disclosures to report.

Research involving human participants animals and Informed consent

The study is a survey and it do not involve human or animal.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The complete details of author involved in Pan-Drain study group are given in acknowledgements.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ricci, C., Pecorelli, N., Esposito, A. et al. Intraperitoneal prophylactic drain after pancreaticoduodenectomy: an Italian survey. Updates Surg 76, 923–932 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-024-01836-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-024-01836-0