Abstract

Oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery (OBCS) is increasingly used to treat breast cancer with the dual purpose of performing a radical oncological resection while minimizing the risk of post-operative deformities. The aim of the study was to evaluate the patient outcomes after Level II OBCS as regards oncological safety and patient satisfaction. Between 2015 and 2020, a cohort of 109 women consecutively underwent treatment for breast cancer with bilateral oncoplastic breast-conserving volume displacement surgery; patient satisfaction was measured with BREAST-Q questionnaire. The 5-year overall survival and disease-free survival were 97% (95%CI 92, 100) and 94% (95%CI 90, 99), respectively. In two patients (1.8%), mastectomy was finally performed due to margin involvement. The median patient-reported score for “satisfaction with breast” (BREAST-Q) was 74/100. Factors associated with a lower aesthetic satisfaction index included: location of tumour in central quadrant (p = 0.007); triple negative breast cancer (p = 0.045), and re-intervention (p = 0.044). OBCS represents a valid option in terms of oncological outcomes for patients otherwise candidate to more extensive breast conserving surgery; the high satisfaction index also suggests a superiority in terms of aesthetic outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast cancer surgical techniques have evolved in patient recovery, oncological safety, and cosmetics toward less invasive approaches [1, 2]. However, although indications for Breast Conserving Surgery (BCS) are more and more increasing, aesthetic results show a great variability with up to 30% of patients reporting unsatisfactory results requiring further surgical correction [3,4,5,6]. Several oncological procedures have been developed from pure plastic cosmetic procedures by means of oncoplastic breast conserving surgery (OBCS) with the aim of improving aesthetic results thanks to immediate breast re-shaping. Another key aspect of oncoplastic surgery is the possibility of reducing the rate of positive margins as well as the need of re-excision or mastectomy due to larger excision volumes of lumpectomy [7,8,9].

Notwithstanding the wide adoption of OBCS procedures, the oncological and cosmetic benefit have not yet been validated in robust studies, mostly as regards their oncologic safety as well as their satisfaction index [1, 10,11,12,13]. On these grounds, the oncologic safety as regards local control, disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were assessed in a cohort of 109 consecutive patient undergoing Wide Local Excision (WLE) and Level II volume displacement reconstruction and immediate contralateral breast symmetrisation. Moreover, patient’s satisfaction index was assessed by means of the BREAST-Q patient reported outcome (PRO) and the association between tumour’s or patient’s features and the aesthetic result were computed [14, 15].

Methods

Between February 2015 and November 2020, a retrospective cohort study was undertaken in patients undergoing OBCS. All patients were consecutively submitted to WLE for breast cancer Level II volume displacement reconstruction and immediate contralateral breast symmetrisation.

Oncoplastic technique was determined by tumour location, tumour size to breast volume ratio, patient’s anatomy, and individual preference. Preoperative drawings were done on the day before surgery to provide guidance to the oncologic procedure thus avoiding any undue skin or glandular excision. According to Clough classification Level II OBCS was chosen since 20–50% of breast volume was to be excised [7]. An intra-operative margin evaluation was always performed; free excision margins required a clear margin according to the rule “no ink on tumor” for invasive cancer, or 2 mm for DCIS. Clips were routinely placed at the cardinal points of the tumour bed before gland re-modelling [16].

Clinico-pathological data including demographic information, tumour, treatment and follow-up were recorded into a standardized institutional database. Adjuvant treatment, as well as neo-adjuvant treatment protocol were defined according to evidence-based guidelines of Breast Cancer management edited by the Italian Association of Medical Oncology (AIOM); each case was weekly discussed at the Institutional Breast Disease Management Team. Patients were checked by annual clinical examination, laboratory, and imaging. Local recurrence was defined as histologically proven recurrent tumour occurring within the same breast or skin envelope.

The patient’s satisfaction index was assessed by means of the validated BREAST-Q questionnaire post-operative reconstruction module; it is a patient reported outcome tool developed to assess satisfaction index and health-related quality of life after different breast cancer surgical procedures. The questionnaire was administered at least one year after surgery and it was scored by means of Q-Score software developed using the Rasch model that gives a score on a 0 to 100 scale, with higher values indicating a greater satisfaction index [14, 15].

The primary endpoint was oncological outcome (loco-regional and/or distant disease control); DFS and OS were computed from the date of surgery. Overall survival curves were obtained by means of Kaplan–Meier method. The secondary endpoint of the study was represented by the patient’s satisfaction index after the OBCS procedure. Univariate analyses to assess the association between patient’s, tumour’s and surgery’s features and aesthetic results were performed with linear regression using the Rasch transformed Breast-Q score as dependent variable. Beta coefficients, 95% confidence interval (CI) and p values were reported. Since only a single Breast-Q measure per patient was available and the time from surgery to questionnaire administration was heterogenous between subjects, we used Spearman’s correlation coefficient to evaluate if the average aesthetic outcome had changed at the increasing of time between surgery and data collection. Two-sided p values below 0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

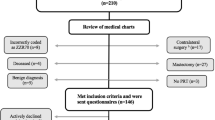

Overall, 134 patients undergoing OBCS procedures were recruited between 2015 and 2020; 19 of them were not included due to missing data. So, 115 patients were contacted by phone and were offered the Breast-Q Test but six of them refused so that the final sample included 109 patients. The mean age of patients was 57.8 years (SD = 10,59); 26 of them (24%) were smokers (Table 1). Mean operative time was 212 min (SD = 56); 79 (72.5%) patients underwent sentinel lymph-node biopsy (SLNB). Axillary lymph node dissection (ALD) was performed in 24 patients (22%) due to intraoperative diagnosis of SLNB macro-metastases; moreover, six patients (5.5%) had immediate ALD due to pre-operative histologic diagnosis of nodal metastasis. As regards the OBCS procedure, an upper pedicle was chosen for the reconstructive part in 36 patients (33,1%) and a lower pedicle in the remaining 73 patients (66,9%) with a mean resected volume equal to 324 g; the nipple-areolar complex (NAC) was amputated and grafted in 36 patients (33%). The mean length of hospitalization was 3.7 days (range: 1 to 9) (Table 2).

Margin involvement at definitive histology occurred in 3 patients (2.7%) cases; based on residual breast volume two of them underwent areola and nipple-sparing mastectomy (1.8%) while another patient was still amenable to conservative resection. Post-operative complications occurred in 19 patients (17%) but they were all managed by conservative treatment (Table 3).

As regard as multimodal treatment, 35 patients (32%) underwent preoperative neo-adjuvant therapy; based on definitive histology, 62 patients (60%) underwent adjuvant chemotherapy and 91 patients (90%) underwent radiation therapy (RT). The mean follow-up was 36 months (SD = 17.7). Local recurrence was histologically diagnosed in seven patients (6.4%). Three patients died, two of them having a previous disease relapse; 5 year OS and DFS were 97% (95%CI 92, 100) and 94% (95%CI 90, 99), respectively (Fig. 1).

The mean time elapsed between surgery and questionnaire administration was 36 months (SD = 17.7). Statistical analysis of BREAST-Q questionnaire responses gave an average patient’s satisfaction index equal to 74/100 (range: 63 to 91), the questionnaire response rate was 80%. The predictors of a negative aesthetic satisfaction index were represented by: tumour location (central quadrant) (p = 0.007); triple negative breast cancer (p = 0.045), and re-intervention (p = 0.044) (Table 4). Moreover, a direct correlation between the average satisfaction index and the length of time elapsed from surgery was observed (Spearman’s rho − 0.29; p = 0.008) (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Oncologic outcome

The paradigm of BCS is to perform a local radical excision while achieving a satisfactory breast shape; oncoplastic surgery aims at combining the principle of “free-edge” resection with the principles of reconstruction for optimizing cosmetic outcomes and minimizing post-operative complications. Oncoplastic procedures includes a wide range of techniques: from simple parenchymal re-arrangement to more complex breast reduction techniques [17, 18].

Oncologic safety would seem to be guaranteed by oncoplastic resection proven the basic principles of local radical resection are respected (“free-edge” resection). Although data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in OBCS procedures are still lacking, the principles of BCS are firmly rooted in solid evidence. As a matter of fact, large RCTs have confirmed that lumpectomy with post-operative RT gives a lower rate of local recurrence as compared to wide local excision alone [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Consequently, oncoplastic surgery should give a comparable if not a superior oncological outcome as compared to standard BCS thanks to breast reduction techniques that enables an even larger tumour excision whenever a less than favourable tumour to breast volume ratio does exists, without compromising cosmetics [20,21,22,23].

To assess the oncological validity of this procedure we tried, at first, to compare our positive margins rate 2.7% with conventional lumpectomy (range: 9% to 36%). Although apparently favourable, such a comparison may not be correct; in fact, the patient candidate for oncoplastic surgery has specific characteristics in tumour width and glandular volume which represent a relative contraindication for pure BCS [24]. Moreover, in agreement with the prospective series of 101 oncoplastic procedures by Clough et al. [25] at the Institute Curie, our findings confirmed that oncoplastic techniques allowed wider resections (324 g vs 222 g) which probably explains the lower number of positive margins (2.7% vs 10%). In another systematic review by De La Cruz et al. [26] regarding the outcome after oncoplastic BCS in 6,011 patients, the positive margin’s rate defined as “no-ink on tumour” was 7.8% which compares favourably with our findings, although a direct comparison is not possible due to the broad spectrum of oncoplastic techniques that were herein considered.

The management of patients with a positive margin after an oncoplastic procedure can be really challenging; as a matter of fact, the clear identification of the tumour’s site after extensive glandular re-shaping may not be so easy and this may even require mastectomy. This might explain the rather high conversion to mastectomy rate (CMR) equal to 5.9% and 6.2% that is reported in two other clinical experiences [25, 26]. Our lower CMR (1.8%) might be explained by routine placement of clips at the cardinal points into the tumour’s cavity after tumoral excision coupled with the systematic operative specimen orientation that may aid in addressing a secondary conservative procedure and avoids a more extensive cavity shaving. Finally, as regards oncological outcomes, our recurrence rate of 6.4% compares favourably with literature data (range: 3.1% to 9.4%) [9, 27]. Notably in the review by Piper et al. [28] including 1,314 patients undergoing BCS with re-shaping oncoplasty, the recurrence rate was lower (3.1% vs 6.4%) even though patients underwent a shorter follow-up (24 vs 36 months).

As for SLNB, the most relevant indication is in patients with invasive breast carcinoma; however, as recommended by NCCN guidelines, it is advisable to perform SLB whenever the primary surgical procedure precludes the biopsy at a later time. In our clinical experience, 12 patients with DCIS underwent operation but the extensive mobilization of the remaining gland as well as the location of the excised nodule would not have permitted SLNB at a later time. [29]

As regard surgical complications, our findings compare favourably with literature data; the rates of post-operative infections and NAC necrosis were similar to the findings of [30]: 2.7% vs 3.2%, and 1.8% vs 1.6%, respectively.

As compared to [26], we experienced an higher rate of axillary seromas (6.4% vs 1%) and this could be explained by the higher frequency of DLA (30/109: 27.5%); moreover, we reported a similar rate of post-operative hematomas (3.6% vs 2.5%); finally, in 3 out of 109 patients (2.7%) skin ischemia (that is, delayed wound healing without tissue necrosis, not requiring local excision) did occur, comparing favourably with literature data: 2.7% vs 2.2%, respectively.

Patient’s satisfaction index

Although local disease control is the mainstay of breast cancer surgery, it should not affect the aesthetic outcome. In this view, great care should be devoted to the patient’s perception of the result of treatment by means of validated instruments, such as the Patient Reported Outcome Questionnaires. Since its proposal in 2009, the Breast-Q has proved to be highly effective and reliable in the patient satisfaction survey; moreover, a recent consensus recommends documenting the benefits of OBCS by means of the BREAST-q [14, 31]. Efforts have been made to assess if OBCS is comparable to other standard of treatments (BCS and mastectomy with or without reconstruction) in terms of aesthetic outcomes.

Literature data seem to suggest the superiority of OBCS over mastectomy or mastectomy with reconstruction [32, 33]. Bazzarelli et al. [15] reported a median patient score of "satisfaction with breast" after OBCS and mastectomy equal to 75/100 and 68/100, respectively. Gardfjell et al. [34] compared a cohort of 144 patients treated with OBCS Level II volume displacement with two groups of BCS with a median patient-reported score for “satisfaction with breast” item of BREAST-q equal to 74/100, 68/100, and 66/100, respectively [35, 36]. These data compare favourably with our findings in the domain "satisfaction with breast" that was equal to 74/100.

Finally, risk factors usually associated with a lower aesthetic result were not confirmed in our experience; so, for instance, neither the focality nor the medium excised volume showed a statistically significance at univariate analysis. Conversely, quadrant involvement, triple negative biology, and re-intervention were correlated with a decreased aesthetic patient perception. The multiple logistic regression model was not performed due to the rather low number of patients in different subgroups so that further studies are required for evaluating risk factors in larger groups of patients. Worth of noting, an interesting behaviour of time-related satisfaction was observed because the satisfaction index was likely to increase as time elapsed from the procedure, with a weak but significant correlation at Spearman's rho -0.29 (p = 0.008). Since the test was given at least one year after surgery, the questionnaire may have been affected by a recall bias (Figs. 3, 4). A similar trend over time was also observed by Nelson et al. [37] who demonstrated an improvement in the aesthetic perception of patients undergoing autologous breast reconstruction over 5 years (68.25 vs 79.65). As also suggested by Acea-Nebril et al. [38], a plurality of factors contribute to the evaluation of aesthetic satisfaction: the length and psychological fatigue of the therapeutic process; the ability to adapt to a new body-image, and the interaction with the medical team. In our view, as time elapses from the conclusion of the treatment planning various factors are likely to positively concur; the physiological improvement of scars; a greater patient’s acceptance of the new physical image and, last but not least, a greater confidence in a positive oncologic outcome.

Conclusions

Oncoplastic procedures give a great advantage in the management of breast cancer patients thanks to more satisfactory aesthetic results with higher patient’s satisfaction index coupled with a more than acceptable oncological safety; as a matter of fact, a wider removal of breast tissue can be accomplished and this may reduce re-excision and mastectomy rates.

References

Rocco N, Catanuto G, Cinquini M, Audretsch W, Benson J, Criscitiello C, Di Micco R, Kovacs T, Kuerer H, Lozza L, Montagna G, Moschetti I, Nafissi N, O’Connell RL, Oliveri S, Pau L, Scaperrotta G, Thoma A, Winters Z, Nava MB (2021) Should oncoplastic breast conserving surgery be used for the treatment of early stage breast cancer? Using the GRADE approach for development of clinical recommendations. Breast 57:25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2021.02.013

Laronga C, Lewis JD, Smith PD (2012) The changing face of mastectomy: an oncologic and cosmetic perspective. Cancer Control 19(4):286–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/107327481201900405

Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER, Jeong JH, Wolmark N (2002) Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347(16):1233–1241. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa022152

Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M, Saccozzi R, Luini A, Aguilar M, Marubini E (2002) Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347(16):1227–1232. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020989

Gabka CJ, Maiwald G, Baumeister RG (1997) Erweiterung des Indikationsspektrums für die brusterhaltende Therapie des Mammakarzinoms durch onkoplastische Operationen Expanding the indications spectrum for breast saving therapy of breast carcinoma by oncoplastic operations Langenbecks Arch Chir Suppl Kongressbd. Heiddelberg

Clough KB, Cuminet J, Fitoussi A, Nos C, Mosseri V (1998) Cosmetic sequelae after conservative treatment for breast cancer: classification and results of surgical correction. Ann Plast Surg 41(5):471–481. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000637-199811000-00004

Clough KB, Kaufman GJ, Nos C, Buccimazza I, Sarfati IM (2010) Improving breast cancer surgery: a classification and quadrant per quadrant atlas for oncoplastic surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 17(5):1375–1391. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-009-0792-y

Audretsch W (1987) Space-holding technic and immediate reconstruction of the female breast following subcutaneous and modified radical mastectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 241:11–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00930983

Shaitelman SF, Jeruss JS, Pusic AL (2020) Oncoplastic Surgery in the Management of Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 38(20):2246–2253. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.02795

Chen JY, Huang YJ, Zhang LL, Yang CQ, Wang K (2018) Comparison of Oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery and breast-conserving surgery alone: a meta-analysis. J Breast Cancer 21(3):321–329. https://doi.org/10.4048/jbc.2018.21.e36

Weber WP, Soysal SD, Zeindler J, Kappos EA, Babst D, Schwab F, Kurzeder C, Haug M (2017) Current standards in oncoplastic breast conserving surgery. Breast 34(1):S78–S81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2017.06.033

Schaverien MV, Doughty JC, Stallard S (2014) Quality of information reporting in studies of standard and oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery. Breast 23(2):104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2013.12.006

Sanidas EE, Fitzal F. (2018) Oncoplastic breast-concerving therapy. Breast cancer management for surgeons. A European Multidisciplinary Textbook. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG. 229–44 Doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40196-

Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Klok JA, Cordeiro PG, Cano SJ (2009) Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg 124(2):345–353. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807

Bazzarelli A, Baker L, Petrcich W, Zhang J, Arnaout A (2020) Patient satisfaction following level ii oncoplastic breast surgery: a comparison with mastectomy utililizing the Breast-Q Questionnaire will be published in Surgical Oncology. Surg Oncol 35:556–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2020.11.001

Fregatti P, Gipponi M, Atzori G, Rosa R, Diaz R, Cornacchia C, Sparavigna M, Garlaschi A, Belgioia L, Fozza A, Pitto F, Boni L, Blondeaux E, Depaoli F, Murelli F, Franchelli S, Zoppoli G, Lambertini M, Friedman D (2022) The Margins’ Challenge: risk factors of residual disease after breast conserving surgery in early-stage breast cancer. In Vivo 36(2):814–820. https://doi.org/10.21873/invivo.12768

Hamdi M (2013) Oncoplastic and reconstructive surgery of the breast. Breast 22(Suppl 2):S100–S105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2013.07.019

Rainsbury RM (2007) Surgery insight: oncoplastic breast-conserving reconstruction–indications, benefits, choices and outcomes. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 4(11):657–664. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncponc0957

Chakravorty A, Shrestha AK, Sanmugalingam N, Rapisarda F, Roche N, Querci Della Rovere G, Macneill FA (2012) How safe is oncoplastic breast conservation? Comparative analysis with standard breast conserving surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 38(5):395–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2012.02.186

Asgeirsson KS, Rasheed T, McCulley SJ, Macmillan RD (2005) Oncological and cosmetic outcomes of oncoplastic breast conserving surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol t 31(8):817–823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2005.05.010

Giacalone PL, Roger P, Dubon O, El Gareh N, Daurés JP, Laffargue F (2006) Lumpectomy vs oncoplastic surgery for breast-conserving therapy of cancer A prospective study about 99 patients. Ann Chir 131(4):256–261

Meretoja TJ, Svarvar C, Jahkola TA (2010) Outcome of oncoplastic breast surgery in 90 prospective patients. Am J Surg 200(2):224–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.09.026

Iwuchukwu OC, Harvey JR, Dordea M, Critchley AC, Drew PJ (2012) The role of oncoplastic therapeutic mammoplasty in breast cancer surgery–a review. Surg Oncol 21(2):133–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2011.01.002

Brouwer de Koning SG, VranckenPeeters MTFD, Jóźwiak K, Bhairosing PA, Ruers TJM (2018) Tumor resection margin definitions in breast-conserving surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis of the current literature. Clin Breast Cancer 18(4):595–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2018.04.004

Clough KB, Lewis JS, Couturaud B, Fitoussi A, Nos C, Falcou MC (2003) Oncoplastic techniques allow extensive resections for breast-conserving therapy of breast carcinomas. Ann Surg 237(1):26–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-200301000-00005

De La Cruz L, Blankenship SA, Chatterjee A, Geha R, Nocera N, Czerniecki BJ, Tchou J, Fisher CS (2016) Outcomes after oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery in breast cancer patients: a systematic literature review. Ann Surg Oncol 23(10):3247–3258. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5313-1

Fitoussi AD, Berry MG, Famà F, Falcou MC, Curnier A, Couturaud B, Reyal F, Salmon RJ (2010) Oncoplastic breast surgery for cancer: analysis of 540 consecutive cases [outcomes article]. Plast Reconstr Surg 125(2):454–462. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181c82d3e

Piper ML, Esserman LJ, Sbitany H, Peled AW (2016) Outcomes following oncoplastic reduction mammoplasty: a systematic review. Ann Plast Surg 76(Suppl 3):S222–S226. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000000720

Breast Cancer V.4.2022. © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2022. All rights reserved. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. Accessed 12 Nov 2022

Losken A, Styblo TM, Carlson GW, Jones GE, Amerson BJ (2007) Management algorithm and outcome evaluation of partial mastectomy defects treated using reduction or mastopexy techniques. Ann Plast Surg 59(3):235–242. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0b013e31802ec6d1

Weber WP, Soysal SD, El-Tamer M, Sacchini V, Knauer M, Tausch C, Hauser N, Günthert A, Harder Y, Kappos EA, Schwab F, Fitzal F, Dubsky P, Bjelic-Radisic V, Reitsamer R, Koller R, Heil J, Hahn M, Blohmer JU, Hoffmann J, Solbach C, Heitmann C, Gerber B, Haug M, Kurzeder C (2017) First international consensus conference on standardization of oncoplastic breast conserving surgery. Breast Cancer Res Treat 165(1):139–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4314-5

Nanda A, Hu J, Hodgkinson S, Ali S, Rainsbury R, Roy PG (2021) Oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery for women with primary breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10(10):13658. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013658.pub2

Santosa KB, Qi J, Kim HM, Hamill JB, Wilkins EG, Pusic AL (2018) Long-term patient-reported outcomes in postmastectomy breast reconstruction. JAMA Surg 153(10):891–899. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1677

Gardfjell A, Dahlbäck C, Åhsberg K (2019) Patient satisfaction after unilateral oncoplastic volume displacement surgery for breast cancer, evaluated with the BREAST-Q™. World J Surg Oncol. 17(1):96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1640-6

Dahlbäck C, Ullmark JH, Rehn M, Ringberg A, Manjer J (2017) Aesthetic result after breast-conserving therapy is associated with quality of life several years after treatment Swedish women evaluated with BCCTcore and BREAST-Q™. Breast Cancer Res Treat 164(3):679–687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4306-5

O’Connell RL, DiMicco R, Khabra K, O’Flynn EA, deSouza N, Roche N, Barry PA, Kirby AM, Rusby JE (2016) Initial experience of the Breast-Q breast-conserving therapy module. Breast Cancer Res Treat 160(1):79–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3966-x

Nelson JA, Allen RJ Jr, Polanco T, Shamsunder M, Patel AR, McCarthy CM, Matros E, Dayan JH, Disa JJ, Cordeiro PG, Mehrara BJ, Pusic AL (2019) Long-term patient-reported outcomes following postmastectomy breast reconstruction: an 8-year examination of 3268 patients. Ann Surg 270(3):473–483. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003467

Acea-Nebril B, García-Novoa A, Cereijo-Garea C (2021) Cosmetic sequelae after oncoplastic breast surgery: long-term results of a prospective study. Breast 27(1):35–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.14142

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Genova within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was waived by the local Ethics Committee in view of the retrospective nature of the study and all the procedures being performed were part of the standard of care.

Informed consent

Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to the interview.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sparavigna, M., Gipponi, M., Carmisciano, L. et al. Oncoplastic level II volume displacement surgery for breast cancer: oncological and aesthetic outcomes. Updates Surg 75, 1289–1296 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-023-01472-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-023-01472-0