Abstract

A tumour-positive proximal margin (PPM) after extended gastrectomy for oesophagogastric junction (OGJ) adenocarcinoma is observed in approximately 2–20% of patients. Although a PPM is an unfavourable prognostic factor, the clinical relevance remains unclear as it may reflect poor tumour biology. This narrative review analyses the most relevant literature on PPM after gastrectomy for OGJ cancers. Awareness of the risk factors and possible measures that can be taken to reduce the risk of PPM are important. In patients with a PPM, surgical and non-surgical treatments are available but the effectiveness remains unclear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The incidence of oesophagogastric junction (OGJ) adenocarcinoma has been gradually increasing both in Western and Asian countries [1, 2]. OGJ cancer involves subcardial, cardia and lower oesophageal adenocarcinomas. The Siewert classification is most often used to classify OGJ cancer. Three types are distinguished to facilitate interpretation of studies on OGJ cancer [3]. However, molecular subtyping of OGJ cancer has identified different subtypes which do not always correlate with the anatomical partition or patterns of nodal dissemination [4]. Hence, the optimal management of OGJ cancer remains uncertain [5].

Most surgeons would agree that the preferred surgical treatment for type I (lower oesophageal adenocarcinoma) is oesophagectomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection. For type III cancers (subcardial adenocarcinoma), total gastrectomy with partial oesophagectomy is performed [6]. For type II cancers (cardia cancer), both surgical approaches may be valid [7]. According to a survey extended to surgeons worldwide between 2013 and 2014, while Asian and South American centres seemed to perform extended total gastrectomy more often, European centres showed a more balanced proportion of the two approaches for Siewert II cancers [8]. Total gastrectomy facilitates a more complete abdominal (D2) lymphadenectomy, avoids postoperative morbidity related to a transthoracic approach and may result in less postoperative functional problems [9,10,11]. The downside of extended gastrectomy for type II cancer is the risk of an incomplete microscopic surgical resection (R1) at the proximal margin (oesophageal margin) [12]. On the other hand, oesophagectomy with gastric tube reconstruction via the transthoracic approach enables an extended two-field lymphadenectomy (abdominal and thoracic) and nearly eliminates the risk of a positive proximal margin. However, this approach is associated with a higher rate of respiratory complications and poorer functional outcomes [9, 10].

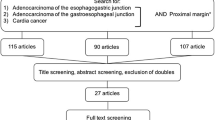

The main goal of any surgical treatment with curative intention is to achieve a complete resection of the tumour. However, the prevalence of a (microscopic) positive resection margin––proximal, distal or circumferential––after extended total gastrectomy for OGJ and gastric cancer ranges from 2.8 to 20% [13]. Here, in this narrative review, we discuss the risk factors, preventive strategies and (postoperative) treatments for positive proximal margin (PPM) after gastrectomy for OGJ cancer.

Causes

A PPM is often only diagnosed on definitive histopathological examination of the resection specimen. This is generally due to an underestimation of the proximal extension of the tumour intraoperatively by the surgeon, often within the submucosal layer. It is therefore important to have a rigorous preoperative assessment by endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). Three endoscopically visible landmarks should be assessed: the Z-line, gastric folds and the diaphragmatic pinch. Submucosal extension of the tumour makes it particularly difficult to judge the degree of oesophageal involvement. In this instance, EUS can be helpful. Furthermore, a minimum length of macroscopic oesophageal safety margin should be respected during surgical resection [14], although most guidelines do not report specifically on the required margin for OGJ cancer (Table 1).

In some patients, the possibility of a PPM is accepted by the surgeon during the operation. For example, if the patient is considered too frail to undergo a more extensive resection. However, one should always consider the need to change the surgical approach and take this into account when selecting patients for total gastrectomy for OGJ cancer.

Distal gastrectomy may treat cancer-related symptoms (e.g., gastric outlet obstruction, bleeding) that are difficult to palliate with other modalities. In selected patients, this approach improves quality of life even when an incomplete tumour resection has been performed [23]. Total gastrectomy is associated with greater morbidity. Hence, many judge palliative total gastrectomy as too aggressive, also given the findings from the REGATTA trial that surgery does not prolong survival compared to chemotherapy alone [6, 24].

Risk factors

Knowledge of the risk factors associated with a PPM could help increase the awareness of the surgical team leading to adaptation of surgical strategy or intraoperative assessment of the resection margin. The most frequently reported risk factors for a positive resection margin are shown in (Table 2). Large diameter of the tumour, advanced T classification, diffuse/mixed Lauren subtype and tumour location at the OGJ all increase the risk of a positive resection margin. In addition, Bissolati et al. found that a small macroscopic surgical margin of less than 2 cm for T1 and less than 3 cm for T2–T4 intestinal type tumours was an independent risk factor for a positive resection margin. This concurs with the recommendations of the Japanese guideline on gastrectomy for cancer [14, 15]. Van der Werf et al. also described a hospital volume of less than 20 gastrectomies per year as an independent risk factor. The benefit in high volume centres is likely to be multi-factorial encompassing staging accuracy, decision making and surgical experience [28].

Does a positive proximal margin matter?

A systematic review and meta-analysis including 19,992 patients found an association of R1 status (circumferential, proximal or distal margin) with poorer overall survival (OS). A positive resection margin was also an independent prognostic factor irrespective of tumour stage [30]. Muneoka et al. analysed 2121 patients and reported a significantly worse 5 year OS and relapse-free survival (RFS) in patients with a positive resection margin in pT2-4 tumours, even when a re-resection was performed to obtain a definite R0 [31]. A worse 5 year recurrence-free survival (RFS) was not observed in patients with pT1 tumours, and only in these early tumours additive surgical resection was of benefit. This study and others [32, 33] found that a positive resection margin is associated with more advanced and aggressive tumours, which may explain the worse 5 year RFS. It would also explain why the recurrence pattern in patients with a positive resection margin is more frequently distant and not locoregional [31, 34]. Hence, worse OS and RFS in PPM cases would be related to an already advanced and aggressive disease, which relapses at distant sites earlier than from residual tumour at the resection margin. According to this theory, resection margin status would only impact on survival in early stage cancers, in which further treatments like re-resection may be of benefit.

How to prevent a positive proximal margin?

Accurate preoperative assessment of the tumour is crucial to limit the chance of an incomplete resection. Endoscopy and computed tomography (CT), often combined with EUS, are mandatory for assessment of T status and the extent of infiltration into the oesophagus. Tumour-positive regional lymph nodes in the mediastinum may also guide the surgeon in defining the surgical approach and as a result the oesophageal resection margin [35]. The value of PET/CT scan for clinical staging of OGJ cancer is not clear but may be used to exclude distant metastases and to evaluate response after neoadjuvant therapy [36]. One of the issues is that signet ring cancers tend to be less FDG avid and so the sensitivity for PET in these high risk tumours (even for longitudinal extension) may be reduced [37].

Data about the biological nature of the tumour in addition to tumour location may be helpful, although there are no clear guidelines yet. Poorly differentiated tumours and the presence of signet ring cells should raise the suspicion of submucosal extension. Neoadjuvant therapy is indicated for locally advanced tumours. Both chemotherapy (FLOT) [38] and chemoradiotherapy (CROSS) [39] have shown improvements in locoregional control and a reduction of positive resection margin rates in OGJ cancers. Hence, neoadjuvant treatment may prevent a PPM in cardia cancer courtesy of tumour down-staging. However, surgical decision making with regard to longitudinal margins should still be guided by initial staging rather than relying on a down-staging effect. This would mandate an accurate assessment of tumour extent at the time of diagnosis.

There is no consensus about the length of macroscopic appearing normal oesophagus that should be resected [40]. Some studies suggested minimum of 2 cm [14, 41]. However, it can be challenging to resect more oesophagus via the abdomen and still leave room for a safe oesophagojejunostomy. Extension of the resection to a partial oesophagectomy or oesophagogastrectomy via a transthoracic approach (right thoracoscopy/thoracotomy or left thoracophrenolaparotomy––Sweet approach) might be needed. For such extended resections, the surgical team must have expertise.

Intraoperatively, manual palpation is helpful in open surgery but is not possible during minimally invasive procedures. Hence, the threshold for conversion (or alternative solutions) should be low if the complete resection cannot be assured by laparoscopy. Intraoperative endoscopy may help assess the proximal margin of the tumour. This could be used in minimally invasive and open approaches. Kawakatsu et al. described the systematic combination of preoperative placement of marking clips and intraoperative endoscopy to determine the surgical margin in patients who undergo laparoscopic extended gastrectomy. They achieved a success rate of 98.9% negative margins during the initial transection [42].

Intraoperative evaluation of the proximal resection margin by performing a frozen section analysis may be the best technique to assess margin status. The accuracy lies between 93 and 99% [27, 43, 44]. False negative results do occur especially in patients with submucosal spread of the tumour, poor differentiation (diffuse or mixed tumours), preoperative neoadjuvant therapy or surgical trauma due to the stapler device. However, intraoperative frozen section analysis is a time and resource-consuming technique, and a pathologist needs to be available in real time. According to current evidence [14, 36], frozen section analysis should be used selectively in patients where the risk of infiltrated margins is high and there is the opportunity to re-resect the oesophagus. This recommendation is in line with Japanese, Italian and AUGIS gastric cancer guidelines [15, 18, 22], in which frozen section examination is considered preferable to ensure an R0 resection in OGJ cancer. Risk factors (Table 2) could help decide in which patients frozen section analysis should be performed. Kumazu et al. defined 6 risk factors for a positive resection margin: remnant gastric cancer, oesophageal invasion, tumour size, undifferentiated type, macroscopic type 4 and pT4 disease. They observed a positive resection margin in 21.3% of their patients when four risk factors were present and 85.7% when five factors were identified. This led to their recommendation to perform a frozen section analysis in patients with four or more risk factors [29].

How to manage a positive proximal margin?

When a positive proximal margin is diagnosed intraoperatively (e.g., by frozen section analysis), re-resection should follow. This may entail the need for changing the surgical approach as discussed earlier. When the proximal margin is positive at histopathological examination of the resection specimen after the operation, further treatments should be considered and tailored to tumour and patient characteristics. There is controversy regarding the benefit of performing a re-resection by a second operation. Some studies have described a lower incidence of local relapse after re-resection, but similar poor survival compared to patients that did not undergo a re-resection [27, 31]. According to Morgagni et al. a positive resection margin reflects advanced disease: regional and distant metastases are influenced by margin status and haematogenous and peritoneal metastatic relapse occurred earlier than local recurrence in patients with a positive resection margin [40]. Hence, some recommend re-resection when feasible and only for patients with N0 status or limited nodal involvement (less than 3–5 positive nodes) [13, 40, 45,46,47]. Furthermore, Bickenbach et al. suggested that only tumours with a limited depth of infiltration (≤ pT1–T2) may gain a survival benefit by re-resection [48].

Multimodal treatment with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) has also been proposed as alternative to surgery. Stiekema et al. showed in a Dutch retrospective cohort study including 409 patients with a R1 resection (proximal, distal or circumferential) that adjuvant CRT was associated with improved survival when compared to patients without adjuvant CRT treatment [49]. In another study, the same authors analysed recurrence-free survival in gastric cancer patients treated with CRT after surgery concluding that an R1 resection was not an adverse prognostic factor [50]. A limitation of both studies was the low lymph node yield in most patients (< 15 nodes) and the heterogeneous population included. The survival benefit in the adjuvant CRT group could be due to better locoregional control in patients without an adequate (D2) lymphadenectomy. In addition, the finding that R1 status was not associated with RFS indicates that other more important factors dictate prognosis. Dikken et al. found that postoperative CRT had a major impact on local recurrence in resectable gastric cancer when a D1 lymphadenectomy was performed [51]. On the contrary, in patients with a D2 lymph node resection, adjuvant CRT did not shown any difference in local recurrence when compared to patients treated with surgery alone. Moreover, Ma et al. found that most patients with positive resection margin had advanced pathologic stage and that adjuvant treatment (28% CRT, 20% chemotherapy alone, 3% radiation alone, 1% reoperation) did not improve RFS or OS. The main failure pattern they found was distant recurrence (72%), suggesting that if patients are considered for adjuvant radiotherapy, they should be carefully selected [34]. Zhou et al. concluded that adjuvant CRT improves locoregional control and that nodal status may be the most important predictor for patient selection: only patients with pN0-2 disease may benefit from additional radiotherapy after R1 resection [52].

Conclusion

Total gastrectomy for cancer aims to completely remove the primary tumour including locoregional lymph nodes. This is defined as achieving negative resection margins and a D2 nodal dissection. The best surgical strategy can only be planned after a comprehensive preoperative assessment of the patient (frailty, comorbidities, patient’s wishes) and location, stage and biological behaviour of the tumour. The surgeon should be involved in every step of this process. Awareness of risk factors for a positive resection margin could help in clinical decision making but unexpected intraoperative findings may lead to adaptation of the surgical management. When a positive resection margin is involved, further treatments options, such as re-resection and/or (chemo) radiation, should be carefully considered in selected cases.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Han WH, Eom BW, Yoon HM, Reim D, Kim YW, Kim MS et al (2019) The optimal extent of lymph node dissection in gastroesophageal junctional cancer: retrospective case control study. BMC Cancer 19:719. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5922-8

Bartel M, Brahmbhatt B, Bhurwal A (2019) Incidence of gastroesophageal junction cancer continues to rise: analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database. J Clin Oncol 37(4 suppl):40–40. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2019.37.4_suppl.40

Rüdiger Siewert J, Feith M, Werner M, Stein HJ (2000) Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: results of surgical therapy based on anatomical/topographic classification in 1,002 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 232(3):353–361. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-200009000-00007

Suh YS, Na D, Lee JS et al (2020) Comprehensive molecular characterization of adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction between esophageal and gastric adenocarcinomas. Ann Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004303

Lin D, Khan U, Goetze TO, Reizine N, Goodman KA, Shah MA et al (2019) Gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: is there an optimal management? Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 39:e88–e95. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_236827

Mariette C, Piessen G, Briez N, Gronnier C, Triboulet JP (2011) Oesophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma: which therapeutic approach? Lancet Oncol 12(3):296–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70125-X

Lutz MP, Zalcberg JR, Ducreux M, Ajani JA, Allum W, Aust D et al (2012) First St Gallen EORTC gastrointestinal cancer conference 2012 expert panel. Highlights of the EORTC St. Gallen international expert consensus on the primary therapy of gastric, gastroesophageal and oesophageal cancer - differential treatment strategies for subtypes of early gastroesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer 48(16):2941–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.07.029

Haverkamp L, Seesing MF, Ruurda JP, Boone J, Hillegersberg VR (2017) Worldwide trends in surgical techniques in the treatment of esophageal and gastroesophageal junction cancer. Dis Esophagus 30(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/dote.12480

Haverkamp L, Ruurda JP, van Leeuwen MS, Siersema PD, van Hillegersberg R (2014) Systematic review of the surgical strategies of adenocarcinomas of the gastroesophageal junction. Surg Oncol 23(4):222–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2014.10.004

Fuchs H, Hölscher AH, Leers J, Bludau M, Brinkmann S, Schröder W et al (2016) Long-term quality of life after surgery for adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: extended gastrectomy or transthoracic esophagectomy? Gastric Cancer 19(1):312–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-015-0466-3

Brown AM, Giugliano DN, Berger AC, Pucci MJ, Palazzo F (2017) Surgical approaches to adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction: the Siewert II conundrum. Langenbecks Arch Surg 402(8):1153–1158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-017-1610-9 (Epub 2017 Aug 12)

Imamura Y, Watanabe M, Oki E, Morita M, Baba H (2020) Esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma shares characteristics with gastric adenocarcinoma: literature review and retrospective multicenter cohort study. Ann Gastroenterol Surg 5(1):46–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/ags3.12406

Cho BC, Jeung HC, Choi HJ, Rha SY, Hyung WJ, Cheong JH et al (2007) Prognostic impact of resection margin involvement after extended (D2/D3) gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a 15-year experience at a single institute. J Surg Oncol 95(6):461–468. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.20731

Bissolati M, Desio M, Rosa F, Rausei S, Marrelli D, Baiocchi GL et al (2017) Risk factor analysis for involvement of resection margins in gastric and esophagogastric junction cancer: an Italian multicenter study. Gastric Cancer 20(1):70–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-015-0589-6

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (2021) Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition). Gastric Cancer 24(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-020-01042-y

Waddell T, Verheij M, Allum W, Cunningham D, Cervantes A, Arnold D (2014) Gastric cancer: ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol 40(5):584–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2013.09.020

Ajani JA, Barthel JS, Bekaii-Saab T, Bentrem DJ, D’Amico TA, Das P et al (2010) NCCN gastric cancer panel. Gastric Cancer J Natl Compr Canc Netw 8(4):378–409. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2010.0030

Allum WH, Blazeby JM, Griffin SM, Cunningham D, Jankowski JA, Wong R (2011) Association of upper gastrointestinal surgeons of great britain and Ireland, the British society of gastroenterology and the British association of surgical oncology. Guidelines for the management of oesophageal and gastric cancer. Gut 60(11):1449–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.228254

Landelijke werkgroep Gastro-intestinale Tumoren. Richtlijn: Maagcarcinoom (2.2) - richtlijnendatabase. 2017 [cited 2022 Jan 24]. Available from: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/gerelateerde_documenten/f/16316/IKNL%20richtlijn%20Maagcarcinoom.pdf

Moehler M, Al-Batran SE, Andus T, Anthuber M, Arends J, Arnold D et al (2011) AWMF; AWMF S3-Leitlinie “Magenkarzinom” - Diagnostik und Therapie der Adenokarzinome des Magens und ösophagogastralen Übergangs (AWMF-Regist-Nr 032–009-OL) [German S3-guideline “Diagnosis and treatment of esophagogastric cancer”]. Z Gastroenterol 49(4):461–531. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1273201

Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS) and Institut National du Cancer (2011) Guide—Affection de longue durée (ALD). Tumeur maligne, affection maligne du tissue lymphatique ou hématopoiétique. Cancer de l’estomac. http://www.has-sante.fr, http://www.e-cancer.fr. Accessed date 24 Jan 2022

De Manzoni G, Marrelli D, Baiocchi GL, Morgagni P, Saragoni L, Degiuli M et al (2017) The Italian research group for gastric cancer (GIRCG) guidelines for gastric cancer staging and treatment: 2015. Gastric Cancer 20(1):20–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-016-0615-3

Hartgrink HH, Putter H, Klein Kranenbarg E, Bonenkamp JJ, van de Velde CJ (2022) Dutch gastric cancer group. Value of palliative resection in gastric cancer. Br J Surg 89(11):1438–43. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02220.x

Fujitani K, Yang HK, Mizusawa J, Kim YW, Terashima M, Han SU et al (2016) REGATTA study investigators. Gastrectomy plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric cancer with a single non-curable factor (REGATTA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 17(3):309–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00553-7

Lee JH, Ahn SH, Park Do J, Kim HH, Lee HJ, Yang HK (2012) Clinical impact of tumor infiltration at the transected surgical margin during gastric cancer surgery. J Surg Oncol 106:772–776

Kim SY, Hwang YS, Sohn TS, Oh SJ, Choi MG, Noh JH et al (2012) The predictors and clinical impact of positive resection margins on frozen section in gastric cancer surgery. J Gastric Cancer 12:113–119

Squires MH 3rd, Kooby DA, Pawlik TM, Weber SM, Poultsides G, Schmidt C et al (2014) Utility of the proximal margin frozen section for resection of gastric adenocarcinoma: a 7-institution study of the US gastric cancer collaborative. Ann Surg Oncol 21(13):4202–4210. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-3834-z

van der Werf LR, Cords C, Arntz I, Belt EJT, Cherepanin IM, Coene PLO et al (2019) Population-based study on risk factors for tumor-positive resection margins in patients with gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 26(7):2222–2233. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07381-0

Kumazu Y, Hayashi T, Yoshikawa T, Yamada T, Hara K, Shimoda Y et al (2020) Risk factors analysis and stratification for microscopically positive resection margin in gastric cancer patients. BMC Surg 20(1):95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00744-5

Jiang Z, Liu C, Cai Z, Shen C, Yin Y, Yin X et al (2021) Impact of surgical margin status on survival in gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Control. https://doi.org/10.1177/10732748211043665

Muneoka Y, Ohashi M, Ishizuka N, Hayami M, Makuuchi R, Ida S et al (2021) Risk factors and oncological impact of positive resection margins in gastrectomy for cancer: are they salvaged by an additional resection? Gastric Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-021-01238-w

Stiekema J, Cats A, Kuijpers A, van Coevorden F, Boot H, Jansen EP et al (2013) Surgical treatment results of intestinal and diffuse type gastric cancer. Implications for a differentiated therapeutic approach? Eur J Surg Oncol 39(7):686–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2013.02.026

Blackham AU, Swords DS, Levine EA, Fino NF, Squires MH, Poultsides G et al (2016) Is linitis plastica a contraindication for surgical resection: a multi-institution study of the U.S. gastric cancer collaborative. Ann Surg Oncol 23(4):1203–11. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4947-8

Ma LX, Espin-Garcia O, Lim CH, Jiang DM, Sim HW, Natori A et al (2020) Impact of adjuvant therapy in patients with a microscopically positive margin after resection for gastric and esophageal cancers. J Gastrointest Oncol 11(2):356–365. https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo.2020.03.03

Mocellin S, Pasquali S (2015) Diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) for the preoperative locoregional staging of primary gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009944.pub2

Fuster D, Mayoral M, Rubello D, Pineda E, Fernández-Esparrach G, Pagès M et al (2015) Is there a role for PET/CT with esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma? Clin Nucl Med 40(3):e201–e207. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0000000000000661

Park K, Jang G, Baek S, Song H (2014) Usefulness of combined PET/CT to assess regional lymph node involvement in gastric cancer. Tumori 100(2):201–6. https://doi.org/10.1700/1491.16415

Al-Batran SE, Homann N, Pauligk C, Goetze TO, Meiler J, Kasper S et al (2019) Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): a randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 393(10184):1948–1957. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32557-1

Shapiro J, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof MCCM, van Hagen P, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BPL et al (2015) Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 16(9):1090–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00040-6

Morgagni P, La Barba G, Colciago E, Vittimberga G, Ercolani G (2018) Resection line involvement after gastric cancer treatment: handle with care. Updates Surg 70(2):213–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-018-0552-2

Yuan P, Yan Y, Jia Y, Wang J, Li Z, Wu Q (2021) Intraoperative gastroscopy to determine proximal resection margin during totally laparoscopic gastrectomy for patients with upper third gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol 12(1):142–152. https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-277

Kawakatsu S, Ohashi M, Hiki N, Nunobe S, Nagino M, Sano T (2017) Use of endoscopy to determine the resection margin during laparoscopic gastrectomy for cancer. Br J Surg 104(13):1829–1836. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10618

Spicer J, Benay C, Lee L, Rousseau M, Andalib A, Kushner Y et al (2014) Diagnostic accuracy and utility of intraoperative microscopic margin analysis of gastric and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 21(8):2580–2586. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-3669-7

Berlth F, Kim WH, Choi JH, Park SH, Kong SH, Lee HJ et al (2020) Prognostic impact of frozen section investigation and extent of proximal safety margin in gastric cancer resection. Ann Surg 272(5):871–878. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004266

Cascinu S, Giordani P, Catalano V, Agostinelli R, Catalano G (1999) Resection-line involvement in gastric cancer patients undergoing curative resections: implications for clinical management. Jpn J Clin Oncol 29(6):291–293. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/29.6.291

Kim SH, Karpeh MS, Klimstra DS, Leung D, Brennan MF (1999) Effect of microscopic resection line disease on gastric cancer survival. J Gastrointest Surg 3(1):24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1091-255x(99)80004-3

Aurello P, Magistri P, Nigri G, Petrucciani N, Novi L, Antolino L et al (2014) Surgical management of microscopic positive resection margin after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a systematic review of gastric R1 management. Anticancer Res 34(11):6283–6288

Bickenbach KA, Gonen M, Strong V, Brennan MF, Coit DG (2013) Association of positive transection margins with gastric cancer survival and local recurrence. Ann Surg Oncol 20(8):2663–2668. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-013-2950-5

Stiekema J, Trip AK, Jansen EP, Aarts MJ, Boot H, Cats A et al (2015) Does adjuvant chemoradiotherapy improve the prognosis of gastric cancer after an r1 resection? Results from a dutch cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol 22(2):581–588. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4032-8

Stiekema J, Trip AK, Jansen EP, Boot H, Cats A, Ponz OB et al (2014) The prognostic significance of an R1 resection in gastric cancer patients treated with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol 21(4):1107–1114. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-013-3397-4

Dikken JL, Jansen EP, Cats A, Bakker B, Hartgrink HH, Kranenbarg EM et al (2010) Impact of the extent of surgery and postoperative chemoradiotherapy on recurrence patterns in gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol 28(14):2430–2436. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9654

Zhou ML, Li GC, Yang W, Deng WJ, Hu R, Wang Y et al (2018) Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus adjuvant chemotherapy for R1 resected gastric cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Radiol 91(1089):20180276. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20180276

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Talavera-Urquijo, E., Davies, A.R. & Wijnhoven, B.P.L. Prevention and treatment of a positive proximal margin after gastrectomy for cardia cancer. Updates Surg 75, 335–341 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-022-01315-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-022-01315-4