Abstract

Surgery is known to be a craft profession requiring individuals with specific innate aptitude for manipulative skills, and visuospatial and psychomotor abilities. The present-day selection process of surgical trainees does not include aptitude testing for the psychomotor and manual manipulative skills of candidates for required abilities. We aimed to scrutinize the significance of innate aptitudes in surgical practice and impact of training on skills by systematically reviewing their significance on the surgical task performance. A systematic review was performed in compliance with PRISMA guidelines. An initial search was carried out on PubMed/Medline for English language articles published over 20 years from January 2001 to January 2021. Search strategy and terms to be used included ‘aptitude for surgery’, ‘innate aptitude and surgical skills, ‘manipulative abilities and surgery’, and ‘psychomotor skills and surgery’. MERSQI score was applied to assess the quality of quantitatively researched citations. The results of the present searches provided a total of 1142 studies. Twenty-one studies met the inclusion criteria out of which six citations reached high quality and rejected our three null hypothesis. Consequently, the result specified that all medical students cannot reach proficiency in skills necessary for pursuing a career in surgery; moreover, playing video games and/or musical instruments does not promote skills for surgery, and finally, there may be a valid test with predictive value for novices aspiring for a surgical career. MERSQI mean score was 11.07 (SD = 0.98; range 9.25–12.75). The significant findings indicated that medical students with low innate aptitude cannot reach skills necessary for a competent career in surgery. Training does not compensate for pictorial-skill deficiency, and a skill is needed in laparoscopy. Video-gaming and musical instrument playing did not significantly promote aptitude for microsurgery. The space-relation test has predictive value for a good laparoscopic surgical virtual-reality performance. The selection process for candidates suitable for a career in surgery requests performance in a simulated surgical environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Traditionally, the selection of surgical trainees has mainly been based on academic achievements and subjective assessments obtained from non-structured interviews [1, 2]. While surgery is known to be a craft profession requiring individuals with specific innate aptitude for manipulative skills, the present-day selection process of surgical trainees in most countries does not include aptitude testing for the visuospatial, psychomotor, and manual manipulative skills of candidates. Consequently, we focused on innate aptitudes in the selection process of suitable candidates for surgery and we defined ‘innate aptitude’ as an ‘inborn or congenital skill, talent, or inclination to perform and complete a task with or without training.

Some researchers quantified the size of medical students’ innate psychomotor skills and recommended to recruit technically gifted candidates for surgery [3], while others concluded that laparoscopy aptitude tests constitute valuable additions to the assessment of candidates for medical specialties that require laparoscopic skills [4].

We aimed to scrutinize the significance of innate aptitude in surgical practice and training by systematically reviewing its significance on the surgical task performance. We also reviewed innate aptitude along with other non-surgical skills, for example, playing video games or musical instruments, while skills in these non-domain-specific areas have been thought to facilitate the learning of aptitudes needed for surgical task performance. In addition, the predictors for innate aptitude for surgical skills were reviewed.

Methods

Protocol

A systematic review was performed in compliance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) guidelines [5].

Search strategy and criteria

A search covering 20 years was carried out by means of PubMed/Medline for English language articles published from January 2001 to January 2021. Search strategy and terms to be used included ‘aptitude for surgery’, ‘innate aptitude and surgical skills, ‘manipulative abilities and surgery’, and ‘psychomotor skills and surgery’.

Only publications related to innate aptitude for surgery were included across all surgical specialties with the exception of veterinary surgery. Surgical tasks in surgical training programs and surgical performance in experimental surgical studies were included. Based on the requirements of the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) to assess the quality of citations, quantitatively researched citations were included [6]. Qualitative papers, reviews, conference abstracts, letters, editorials and commentaries, protocols, and non-English publications were excluded.

The retrieved citations were read in full text for further assessment for eligibility. Risk of bias was assessed across studies.

Quality measurement

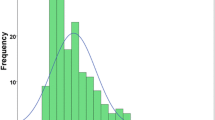

The Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) was applied to assess the quality of quantitatively researched citations [6]. The MERSQI contains ten items that reflect six domains of study quality including study design, sampling, type of data, validity of evaluation instrument, data analysis, and outcomes. The maximum score for each domain was three with a potential range from 5 to 18. The MERSQI score represents the mean of two independent assessors’ quality estimations of each citation. For the currently included 21 citations, the quality mean was 11.07 (SD = 0.98) scores and the scores ranged from 9.25 to 12.75. Scores < 9 would have revealed insufficient quality but were not present. Scores from 9 to 10.25 represented low quality, scores from 10.50 to 11.75 revealed moderate quality, and ≤ 12 scores indicated high quality. The distribution of aptitude scores was found to be normal when computed by one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (two-tailed p = 0.062 > 0.05; Lilliefors corrected).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

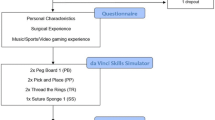

The results of the present searches over 20 years provided a total of 1142 studies. These studies were screened and assessed for eligibility. After the inspection of the titles and abstracts, these elements were systematically reviewed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 113 papers were retrieved out of which 87 papers were excluded (Fig. 1). After administration of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 21 articles remained in this review. Search items were studied from the nature of the article, date of publication, forum of publication, aim and main findings in relation to the effect of innate aptitude on the surgical performance, as well as quality scores in agreement with the MERSQI protocol.

Results of individual studies

The definitions and tests of various forms of innate aptitudes are shown in Table 1. Tabular analysis of the revealed citations is presented in Table 2. Out of the 21 citations, 11 benefited from virtual reality simulators (VRS) and ten from dry lab. No significant difference between quality scores was found between these two groups VRS M 10.98 [SD 0.96] vs. M 11.20 [SD 0.99]; p = n.s.). Medical students and surgical novices participated in 18 citations, trainees in three citations, and they were compared to expert surgeons in four citations.

Out of the 21 citations, six reached high quality through MERSQI ratings and our three null hypotheses were rejected based on the findings from these high-quality citations (Table 3) which significantly overridden the other citations. The difference between high-quality papers and medium/low quality was significant (M 12.13 [SD 0.32] > M 16.65 [SD 0.82], t [19] = 4.221, p < 0.0005 two-tailed).

The first null hypothesis

‘Regardless of level of innate aptitude, all medical students can reach proficiency in skills necessary for pursuing a career in surgery’ was rejected, while aptitude plays a key role in learning advanced skills necessary for laparoscopy [13, 24]. Namely, Buckley et al. tested innate aptitude by scoring surgical novices. Group A (n = 10) included students with a high level of innate aptitude and another group B (n = 10) comprised students with low level of innate aptitude in visual spatiality, depth perception, and psychomotor skills [24]. The results indicated that group A with novices with high aptitude achieved proficiency after a mean of seven attempts (range 4–10). In group B with novices with low aptitude altogether 30% achieved proficiency after a mean of 14 attempts (range 10–16). In group B, 40% demonstrated improvement but did not attain proficiency, and a total of 30% failed to progress. In other words, aptitude plays a significant role in learning advanced skills as candidates with low innate ability were unable to reach proficiency despite repeated training.

Gallagher et al. suggested that perceptual skills connected to recovery of data about depth from pictures are applicable to changes in laparoscopic routine [13]. The ability to recover depth from pictures develops progressively during childhood, and the skill improves with operating laparoscopically. While no differences between experienced surgeons and other groups regarding PicSOr were observed, it seems probable that the skill is fixed in adulthood. Therefore, preselection for pictorial skills is reasonable, while training does not compensate for pictorial-skill deficiency. Gallagher et al. recommend that a relevant battery of tests could and should include measures of perceptual skills related to recovering information about depth from pictures. PicSOr provides a simple measure of talent in that area. As such, it offers a possible way of assessing which trainees have the fundamental visuospatial and depth perception aptitudes to eventually learn Minimal Access Surgery (i.e., natural aptitude). Yet, both Buckley et al. and Gallagher et al. supported the use of objective selection processes based on innate aptitude to choose suitable trainees who are likely to succeed in surgery, if selected [13, 24].

The second null hypothesis

Playing video games and/or musical instruments promote skills for microscopic surgery through transfer from gaming and playing instruments. The null hypothesis was rejected based on findings in two high-quality studies [26, 30].

Osborn et al. determined whether video gaming or musical instrument playing would predict aptitude for a microsurgical task [26]. Altogether 46 students performed a microsurgical task using a novel simulator and their performance was assessed by blinded raters. There was no correlation between video gaming and improved microsurgical performance. Most students played a musical instrument. Within this group, the highest scores were obtained by musicians who began playing before the age of 6. However, musicians did not obtain higher scores than non-musicians, regardless of their age of commencement. Thus, no improvement in microsurgical aptitude was seen neither in students who had a history of video gaming nor from musical instrument playing.

Moglia et al. studied a volunteer sample of 155 medical students and the large majority (83.2%) of the participants was found to possess average aptitude for surgery [30]. Out of nine top performers, five had experienced both video-gaming and musical instrument playing, but Spearman rho correlation both with video-gaming and musical instrument playing was non-significant. Seventeen students underperformed, eight with skills in video games and musical instrument, three with experience in video-gaming; and five with musical instrument playing but Spearman rho correlation with video games and musical instruments was non-significant. Also, the 129 subjects with average performances had no significant Spearman rho neither with video games nor with musical instruments.

The third null hypothesis

There are no tests with predictive value for novices aspiring for a surgical career. The null hypothesis was rejected based on findings by Francis et al. and Schijven et al. [11, 14]. Francis et al. administered The Space Relations Test (SRT) to 20 master endoscopic surgeons (age median 47; range 38–57) compared to 20 medical students (age median 21; range 18–28) with no previous experience in surgery [11]. The researchers found that if the age norm for this test is followed, SRT is a valuable test for surgical aspirants. Francis et al. claimed that because of a possible age factor effect, it would be unwise to dismiss tests of visuospatial ability in aptitude assessments for selection of surgical trainees. The test’s age norm is based on an analysis of 236 adults (mean age 30.25 years) receiving career guidance in the United States with varied educational background. SRT is a subtest of the Technical Abilities Battery of the Differential Aptitude Tests (Psychological Corporation Ltd.). It evaluates the aptitude to reconstruct a three-dimensional object from a two-dimensional pattern as well as the ability to conceptualize the object when rotated in space. The test consists of 50 tasks. For each task, there is one unfolded test diagram and four optional folded patterns, one of which results in the correct folded diagram. The novice aspiring for a surgical career must identify the appropriate alternative [9].

Schijven et al. [14] found that SRT had a predictive and selective value in identifying people who achieve good laparoscopic surgical act on the Xitact simulator. SRT is highly correlated with The Abstract Reasoning Test (ART) [11]. Partakers scoring > 45 on the SRT and > 35 on ART are unlikely to be unsuccessful on the Xitact simulator. Yet, a “good” surgeon is more than accumulated knowledge and psychomotor abilities. Personality traits, i.e., interest, endurance, empathy, stress-resistance, and decision-making abilities, are necessary for becoming a good surgeon.

Risk of bias within and across studies

The Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) was designed to evaluate the methodological quality of medical education research [6]. While the MERSQI has been demonstrated to be a reliable and valid instrument for measuring methodological quality in medical education research, we applied it in our systematic review. The risk of bias within studies consisted of the small groups of participants, which fact always is accompanied with bigger SD making it more difficult to get significant results. It was claimed that MERSQI is not limited to intervention studies only, but is appropriate for all quantitative studies [32]. This constitutes the risk of bias across the present study as we had to exclude qualitative and review studies. The MERSQI scale was found to be somewhat robust and clumsy as well as demanded discussions between raters for the final inter-rater consensus about citations’ quality scores. The maximum scores of MERSQI was 18, but no citation came close to that number.

Discussion

We studied the effect of innate aptitude on the surgical performance. High-quality studies supported the idea that the selection of medical students to a career in surgery should be based not only on academic achievements and subjective assessments such as non-structured interviews [1, 2] but on objective measures considering the surgery’s craft-natured profession requiring individuals with specific innate aptitude for visuospatial and for manipulative skills, not only suitable for open surgery, but more so for sophisticated laparoscopic task performance.

Innate aptitude plays a major role in learning skills necessary for laparoscopy [13, 24]. High innate aptitude for surgery results in better outcomes in operating theaters. It was previously revealed that the most encouraging skills correlating with laparoscopic and arthroscopic simulator success were those of visuospatial aptitude, psychomotor skills, and perceptual talent [33]. All medical students cannot reach proficiency in some of the skills relevant for laparoscopy [34]. On the other hand, it has also been disclosed that aptitude tests can be used to predict parts of the individual differences in laparoscopic skills in forms of useful additions to simulator-based assessment [35]. A laparoscopy aptitude test could help low-aptitude students to make their right career decision. They can invest their time and energy in a specialty that more closely matches their talent.

The idea that video gaming and/or playing musical instruments would promote skills for microscopic surgery did not get support [25, 26]. Tetris is one of the leading video games in the world and has sold in more than 202 million copies. Tetris requires intelligence and skill and was speculated to benefit laparoscopic performance, although video-gaming is a non-domain aptitude. In contrast, domain-specific competence depends on genes, environment, practice, and traits in complex interactions [36]. Two previous experiments explored if expertise on Tetris transfers to measures of spatial ability [37]. Tetris-player experts surpassed non‐Tetris players on mental rotation of shapes if the shapes were identical to or almost similar to those of Tetris, but did not benefit other tests of spatial ability. All in all, the results suggested that spatial expertise is highly domain‐specific and does not transfer broadly to other domains [36].

Also, transfer from playing music to laparoscopic task performances in surgical novices does not occur [36]. The researchers studied the association between music practice and accuracy of motor timing and discovered that the relationship disappeared when controlling for genetics and shared environment. This agrees with a twin study on training of the rotary pursuit task, in which the genetic influences on performance as well as on rate of learning were disclosed [38]. In other words, the selection of medical students to a career in surgery should neither rely on student’s experience of video games nor on their experience of playing musical instruments.

It was claimed that no single test has been reported to reliably predict technical performance across the range of techniques and skills required of surgical trainees [39]. Nevertheless, visual spatial tests have demonstrated some promise, but only in predicting performance on a specific subset of surgical tasks. The SRT was used to assess visuospatial ability and can be used in aptitude assessment for selection of surgical trainees [11]. The importance of visuospatial ability in surgery has been emphasized and it has been suggested that visuospatial ability is related to competency and quality of results in complex surgery, and could be used in resident selection, career counseling, and training [40]. Furthermore, the assessment of visuospatial ability and the use of SRT for selection of surgical trainees have been previously well supported [14]. SRT has been administered to 1391 aspirants to a dental school in a study. Little correlation was found between SRT and GCE 'A' level grades, showing that SRT measured different aptitude but disclosed a strong relationship between students scoring poorly on SRT and then resigning from the course or failing to graduate on time [41].

Traditionally, academic achievement is a strong predictor of successful completion of training programs and success in end-of-training examinations, but does not predict clinical performance during the training program [42]. Therefore, that kind of achievement can be complemented with aptitude tests [33]. Nevertheless, motivation, perseverance, and purposeful practice were considered as greater determinants of technical performance than a score on an aptitude test [35]. Yet, the importance of testing non-technical skills for surgeons by NOTSS was stressed, but it has been claimed that the best option to select candidates suitable for a career in surgery would be assessments in a simulated surgical environment, where the artificial environment replicates the reality, and where the candidates’ skills in forms of teamwork, communication, and response to stress are assessable [43]. However, a simulated operating theater is not achievable in every hospital, and therefore, NOTTS could be used and applied for an early evaluation and training of non-technical skills for medical students aspiring to become surgeons.

Clinical implication and future direction

The role of psychological motivation for surgical activity is underestimated. The psychological motivation for a career in medical specialties of 318 medical students was studied [44]. Aspects influencing the Specialty preference (SP) were reduced by Principal Component Analysis to the components: 'working situation' (comprising extrinsic motivation), 'specialty prospect' (containing intrinsic motivation), and 'career opportunity' (including dual motivation). Males’ common SP’s were surgical specialties; females interested in surgical specialties were more career driven (i.e., liked prestige, research opportunity, career prospects, and got encouragement from family and professor). Males pursuing surgical specialties, scored higher on 'career opportunity', and they were both intrinsically and extrinsically motivated for their SP. Extrinsically motivated students looked for external sources of support, they needed external rewards for hard work. Yet, medical students were found to over- or under-estimate their factual ability in subjective self-ratings. This fact made us doubt that psychological motivation is enough to successfully pursue a career in surgery which requests complex technical skills. The role of psychological motivation for surgical activity can be the subject for future studies.

The effectiveness of admission interviews has been evaluated as a tool for predicting candidates' performance in the medical program, and it was found in the regression analysis that, for example, in year 2, that the interview scores explained only 3.9% of the variance in the performance in the selection process The selection tools altogether explained 13.5% of that variance and the tools did not correlate with each other. The result was explained in terms that the selection tools worked well alone, but they did not correlate highly with each other, or the interview process did not measure what it was supposed to measure [45].

Therefore, there is a need to evaluate the effectiveness of admission tools against a broad range of outcomes within and beyond the medical program [46]. Our review provided useful examples of selection tools for the measurement of students’ different aptitudes by testing innate aptitudes disclosing suitability for a competent career in surgery.

Conclusion

The significant findings indicated that medical students with low innate aptitude are not able to reach skills necessary for a competent career in surgery. Training does not compensate for pictorial-skill deficiency, and a skill is needed in laparoscopy. Furthermore, spatial ability does not benefit from video gaming. Also, playing music instruments does not benefit aptitude for microscopic surgery. The mentioned talents are domain-specific competences contingent on genetic factors, environmental essentials, practice, and personality traits. These aspects interact with each other in a multifaceted way. Therefore, the selection of candidates suitable for a career in surgery should ideally be assessed in a simulated surgical environment.

References

Bingham WV (1937) Aptitudes and aptitude testing. Harper and Brothers Publishers, New York

Cuschieri A (1995) Whither minimal access surgery: tribulations and expectations. Am J Surg 169:9–19

Moorthy K, Munz Y, Sarker SK, Darzi A (2003) Objective assessment of technical skills in surgery. BMJ 327(7422):1032–1037

Graham KS, Deary IJ (1991) A role for aptitude testing in surgery? J R Coll Surg Edinb 36(2):70–74

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535

Reed DA, Cook DA, Beckman TJ, Levine RB, Kern DE, Wright SM (2007) Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. JAMA 298(9):1002–1009

Cowie R (1998) Measurement and modelling of perceived slant in surfaces represented by freely viewed line drawings. Perception 27(5):505–540. https://doi.org/10.1068/p270505 (PMID: 10070553)

Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, Grant I, Temkin NR (1999) Test–retest reliability and practice effects of expanded Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 5(4):346–356

(1996) DAT for selection technical abilities battery manual, Psychological Corporation, 5th edn. Harcourt Brace, New York

Carroll JB (1993) Human cognitive abilities: a survey of factor-analytic studies (No. 1). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Francis NK, Hanna GB, Cresswell AB, Carter FJ, Cuschieri A (2001) The performance of master surgeons on standard aptitude testing. Am J Surg 182(1):30–33

Dashfield AK, Lambert AW, Campbell JK, Wilkins DC (2001) Correlation between psychometric test scores and learning tying of surgical reef knots. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 83(2):139

Gallagher AG, Cowie R, Crothers I, Jordan-Black JA, Satava RM (2003) PicSOr: an objective test of perceptual skill that predicts laparoscopic technical skill in three initial studies of laparoscopopic performance. Surg Endosc Other Interv Tech 17(9):1468–1471

Schijven MP, Jakimowicz JJ, Carter FJ (2004) How to select aspirant laparoscopic surgical trainees: establishing concurrent validity comparing Xitact LS500 index performance scores with standardized psychomotor aptitude test battery scores. J Surg Res 121(1):112–119

Hislop SJ, Hsu JH, Narins CR, Gillespie BT, Jain RA, Schippert DW et al (2006) Simulator assessment of innate endovascular aptitude versus empirically correct performance. J Vasc Surg 43(1):47–55

Rosenthal R, Gantert WA, Scheidegger D, Oertli D (2006) Can skills assessment on a virtual reality trainer predict a surgical trainee’s talent in laparoscopic surgery? Surg Endosc Other Interv Tech 20(8):1286–1290

Cope DH, Fenton-Lee D (2008) Assessment of laparoscopic psychomotor skills in interns using the MIST Virtual Reality Simulator: a prerequisite for those considering surgical training? ANZ J Surg 78(4):291–296

Nomura T, Miyashita M, Shrestha S, Makino H, Nakamura Y, Aso R et al (2008) Can interview prior to laparoscopic simulator training predict a trainee’s skills? J Surg Educ 65(5):335–339

Van Herzeele I, O’Donoghue KG, Aggarwal R, Vermassen F, Darzi A, Cheshire NJ (2010) Visuospatial and psychomotor aptitude predicts endovascular performance of inexperienced individuals on a virtual reality simulator. J Vasc Surg 51(4):1035–1042

Alvand A, Auplish S, Gill H, Rees J (2011) Innate arthroscopic skills in medical students and variation in learning curves. JBJS 93(19):e115

Kennedy AM, Boyle EM, Traynor O, Walsh T, Hill ADK (2011) Video gaming enhances psychomotor skills but not visuospatial and perceptual abilities in surgical trainees. J Surg Educ 68(5):414–420

Nugent E, Hseino H, Boyle E, Mehigan B, Ryan K, Traynor O, Neary P (2012) Assessment of the role of aptitude in the acquisition of advanced laparoscopic surgical skill sets. Int J Colorectal Dis 27(9):1207–1214

Buckley CE, Kavanagh DO, Gallagher TK, Conroy RM, Traynor OJ, Neary PC (2013) Does aptitude influence the rate at which proficiency is achieved for laparoscopic appendectomy? J Am Coll Surg 217(6):1020–1027

Buckley CE, Kavanagh DO, Nugent E, Ryan D, Traynor OJ, Neary PC (2014) The impact of aptitude on the learning curve for laparoscopic suturing. Am J Surg 207(2):263–270

Moglia A, Ferrari V, Morelli L, Melfi F, Ferrari M, Mosca F, Cuschieri A (2014) Distribution of innate ability for surgery amongst medical students assessed by an advanced virtual reality surgical simulator. Surg Endosc 28(6):1830–1837

Osborn HA, Kuthubutheen J, Yao C, Chen JM, Lin VY (2015) Predicting microsurgical aptitude. Otol Neurotol 36(7):1203–1208

Moore EJ, Price DL, Van Abel KM, Carlson ML (2015) Still under the microscope: can a surgical aptitude test predict otolaryngology resident performance? Laryngoscope 125(2):E57–E61

Groenier M, Groenier KH, Miedema HA, Broeders IA (2015) Perceptual speed and psychomotor ability predict laparoscopic skill acquisition on a simulator. J Surg Educ 72(6):1224–1232

Siska VB, Ann L, Gunter de W, Bart N, Willy L, Marlies S, Marc M (2015) Surgical Skill: Trick or Trait? J Surg Educ 72(6):1247–1253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.05.004

Moglia A, Morelli L, Ferrari V, Ferrari M, Mosca F, Cuschieri A (2018) Distribution of innate psychomotor skills recognized as important for surgical specialization in unconditioned medical undergraduates. Surg Endosc 32(10):4087–4095

Mitchell PB, Ostby S, Mara KC, Cohen SL, Chou B, Green IC (2019) Career interest and psychomotor aptitude among medical students. J Surg Educ 76(6):1526–1533

Smith RP, Learman LA (2017) A plea for MERSQI: the medical education research study quality instrument. Obstet Gynecol 130(4):686–690

Mason EM, Deal MJ, Richey BP, Baker A, Zeini IM, Service BC, Osbahr DC (2021) Innate arthroscopic and laparoscopic surgical skills: a systematic review of predictive performance indicators within novice surgical trainees. J Surg Educ 78(1):178–200

Grantcharov TP, Funch-Jensen P (2009) Can everyone achieve proficiency with the laparoscopic technique? Learning curve patterns in technical skills acquisition. Am J Surg 197(4):447–449

Kramp KH, van Det MJ, Hoff C, Veeger NJGM, Hoedemaker HOTC, Pierie JPE (2016) The predictive value of aptitude assessment in laparoscopic surgery: a meta-analysis. Med Educ 50(4):409–427

Ullen F, Hambrick DZ, Mosing MA (2016) Rethinking expertise: A multifactorial gene–environment interaction model of expert performance. Psychol Bull 142(4):427

Sims VK, Mayer RE (2002) Domain specificity of spatial expertise: the case of video game players. Appl Cognit Psychol 16(1):97–115

Fox PW, Hershberger SL, Bouchard TJ (1996) Genetic and environmental contributions to the acquisition of a motor skill. Nature 384(6607):356–358

Louridas M, Szasz P, de Montbrun S, Harris KA, Grantcharov TP (2016) Can we predict technical aptitude? Ann Surg 263(4):673–691

Wanzel KR, Ward M, Reznick RK (2002) Teaching the surgical craft: from selection to certification. Curr Probl Surg 39(6):583–659

Smith BG (1989) A longitudinal study of the value of a spatial relations test in selecting dental students. Br Dent J 167(9):305–308

Maan ZN, Maan IN, Darzi AW, Aggarwal R (2012) Systematic review of predictors of surgical performance. Br J Surg 99(12):1610–1621

Ragonese M, Di Gianfrancesco L, Bassi P, Sacco E (2019) Psychological aptitude for surgery: the importance of non-technical skills. Urol J 86(2):45–51

Boghdady ME, Ewalds-Kvist BM, Duffy K, Hassane A, Kouli O, Ward B et al (2020) Medical students' specialty preference relative to trait emotional intelligence and general self-efficacy. Educ Med J 12(2)

Ma C, Harris P, Cole A, Jones P, Shulruf B (2016) Selection into medicine using interviews and other measures: much remains to be learned. Issues Educ Res 26(4):623–634

Shulruf B, O’Sullivan A, Velan G (2020) Selecting top candidates for medical school selection interviews-a non-compensatory approach. BMC Med Educ 20:1–8

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof Sir Alfred Cuschieri for inspiring us conducting this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El Boghdady, M., Ewalds-Kvist, B.M. The innate aptitude’s effect on the surgical task performance: a systematic review. Updates Surg 73, 2079–2093 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-021-01173-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-021-01173-6