Abstract

Pancreatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (pSPN) is a rare exocrine neoplasm, which generally occurs in young women. This study analyses the clinical characteristics of pSPN in male patients through a systematic review of the literature, adding three new cases from our institution. We reviewed our experience in Pspns, and we performed a systematic review of pSPN of all articles published in English in PubMed and SCOPUS from 1980. Using the final included articles, we evaluated clinic-pathological features, surgical treatment and prognosis of male patients affected by pSPN. From the literature review and our cases, we collected 246 male patients with a proven pSPN. Mean age was 34.3 (range 4–78) years, with 26.2% patients younger than 18 years. Patients were asymptomatic in 35.9% of cases, despite a mean tumour size of 6.3 cm. In 63.7% of cases, the pSPN was located in the body–tail region. Distant metastases were reported at diagnosis in only 10 (4.1%) patients. A correct pre-operative diagnosis (including cytopathology) was provided in 53.6% of patients, with only 40 fine-needle aspiration/biopsy performed. Standard pancreatic resections represented 90.4% of surgical procedures. Beta-catenin and progesterone receptors were positive at immunostaining in 100% and 77.8% of cases, respectively. Fourteen (7.2%) patients relapsed after a mean disease-free survival of 43.1 months. After a mean follow-up of 47 (range 4–180) months, 89.5% of patients were alive and disease-free. Although rare, when dealing with a solid-cystic pancreatic mass, even in asymptomatic male patients, a pSPN should be considered as a possible diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 1959, the pathologist Virginia Kneeland Frantz firstly described a solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) of the pancreas in a 2-year-old male patient [1]. It is a low-grade malignant tumour lacking a specific line of pancreatic epithelial differentiation [2], accounting for 1–3% of all pancreatic tumours [3]. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm is known for its strong female preponderance (F:M = 10:1); in fact, it affects women less than 30 years old in 85% of cases [4], while men are rarely affected. About 20–25% of SPNs occur in patients younger than 18 years [4].

The clinical presentation is usually non-specific. The most frequent symptoms are abdominal pain or discomfort, a palpable mass, and compression of the stomach, duodenum, or main biliary duct related to the large size of the tumour [5]. Some patients are completely asymptomatic, and the SPN may be detected incidentally by imaging studies, or by routine physical examination. Laboratory tests are normal, hormonal activity is absent and tumour markers are generally unremarkable [5].

A complete surgical excision is curative in patients with a SPN limited to the pancreas. Up to 10–15% of SPNs show malignant behaviour and distant metastases, usually to the liver and peritoneum [6]. Nevertheless, SPN is generally associated with an excellent long-term prognosis, with a reported 10-year disease-specific survival rate of 96% [7], even when including the resection of distant metastases [8]. Currently, no specific chemotherapy regimens are available.

In recent years, the reported number of SPNs in the English literature has increased sevenfold since 2000 [9]. The knowledge of this rare pancreatic tumour has become better than before, and the quality and use of cross-sectional imaging has improved [9]. The interest in this disease is increasing, especially in those rare SPNs that develop in male patients. In this specific field, the available literature is limited. We report three new cases of pancreatic SPN in male patients, and we performed a review of the English literature of pancreatic SPN in males from 1980, evaluating their clinic-pathological features, surgical treatment and outcome.

Patients and methods

Literature search

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines were followed when performing and reporting this systematic review [10]. PubMed and SCOPUS were queried from January 1, 1980 to May 12, 2020, using predetermined search strings (Appendix 1). Because of the various definitions associated with SPN of the pancreas, according to the WHO classification of tumours 2019 [2], the related terminology was used in the search strategy, that included the terms “pancreas”, “pseudopapillary”, “solid cystic” and “papillary cystic” tumour.

Inclusion criteria

Full-text studies published in English language after 1980 were included. In 1981, the use of computed tomography (CT) scan was first reported for SPN diagnosis [11], increasing the diagnostic accuracy for pre-operative diagnosis, and in 1981 Klöppel et al. [12] described the SPN as a well-defined pancreatic cystic tumour. After deduplication of common reports between PubMed and SCOPUS, all publications related to pancreatic SPNs (histologically or cytologically confirmed), which included male patients and reported a description of patient and tumour characteristics (demographics, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome) were considered for the eligibility phase.

Studies selection and data extraction

Two investigators (A.G.Z. and A.D.) independently reviewed all the records left after the screening phase. In case of disagreement, a third investigator (A.C.M.) resolved the conflict. We excluded full texts not found from the available resources. Case series including female patients with aggregate clinical data were excluded. To avoid duplication of cases, the clinical data reported were cross-referenced by the country of origin, and then by the centre from which the case originated. Variables that were recorded included: patient age and symptoms; tumour features (size, location, and presence of distant metastases); pre-operative diagnosis (imaging studies, fine-needle aspiration-FNA or biopsy); type of surgery; immunohistochemical data (β-catenin, alpha1-antitrypsin, vimentin, progesterone receptor, CD10, and CD56); time of follow-up; complementary treatment performed at diagnosis or after disease recurrence (i.e. chemotherapy/systemic treatment, loco-regional treatment); and final outcome (disease recurrence, disease-free survival and status). If some data of the selected studies were reported as aggregate with that of female patients, these were considered as “not available”. When data were reported for some but not all patients, we presumed that the finding was present in the patients reported and absent in the others.

Institution data search and case presentation

Male patients who underwent surgery for a pancreatic SPN from January 1986 to December 2017 in the study centre were enrolled. Their clinical records were retrieved, and retrospectively evaluated from clinical charts. The same data collected from the literature search were analysed for the cases from our institution, and in addition, we reported pancreatic tumour markers, and mitotic index and/or Ki-67 labelling index. All the patients had a regular follow-up, with clinical evaluation and imaging studies (CT scan, and/or magnetic resonance imaging-MRI). Follow-up closed in December 2019. The status of patients was defined at the last follow-up visit by medical reports.

Results

Literature selection and systematic review

The literature search generated 3145 reports, and after deduplication and screening, 292 full-text articles met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Twelve studies were excluded because they reported on common cases from the same institutions. Six articles with English full text not available and 43 full texts not found from the available sources were also excluded. Other 109 articles reporting aggregate male and female patients’ data were not eligible for the review. Finally, 122 studies were included in the systematic review for qualitative synthesis (Appendix 2). These included 49 (40.2%) case reports and 73 (59.8%) case series of female and male patients. Most studies (107) were published after 2000, with only 15 studies published between 1980 and 2000. We reviewed 243 cases of pancreatic SPN in male patients.

Presentation of our cases

From 1986 to 2017, 19 patients with pancreatic SPNs were operated in our Surgical Unit. Three of them (15.8%) were male patients (Table 1).

Case 1

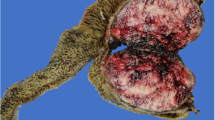

In 2010, an asymptomatic 75-year-old man was incidentally diagnosed at the abdominal ultrasound (US) with a solid lesion close to the splenic hilum. The CT scan confirmed a 4.5 cm, hypodense, solid mass with a minor cystic component, localised at the tail of the pancreas. A partially cystic signal intensity with peripheral dishomogeneous enhancement and multiple septa within the cystic component was evident at MRI. The 18F- fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)-CT showed no abnormal tracer uptake, and CA19.9 was within the normal range. The radiologist suspected a large serous cystadenoma, but due to the uncommon prevalent solid component, the surgeon considered safer to resect it and the patient underwent distal pancreatectomy. Pathology showed a pancreatic SPN, with a central haemorrhagic area. Mitotic index was 0/10 HPF, and immunohistochemistry was positive for β-catenin (Fig. 2) and progesterone receptors. The post-operative course was uneventful. The patient was alive without disease 115 months after surgery.

Case 2

In 2017, a 20-year-old man presented with upper abdominal discomfort and weight loss since 1 year. A CT scan revealed a dishomogeneous mass of 5.7 cm in the pancreatic tail, with a fluid appearance with a dense component, and a complete encasement of the splenic vein. The MRI confirmed a 5.0 cm mass with a dishomogeneous fluid content, and a peripheral anterior solid component. At the 18F-FDG PET-MRI, the pancreatic mass showed a hypermetabolic border (SUVmax 6.5) and a hypometabolic core. Tumour markers were negative. The patient underwent distal pancreatectomy for suspected SPN. Histology reported a SPN with large necrotic areas, infiltration of the pseudocapsule and perineural invasion. Immunohistochemistry was positive for β-catenin, progesterone receptors and NSE. The patient had an uneventful post-operative course. He had no evidence of disease recurrence 34 months after surgery.

Case 3

In 2017, a 14-year-old boy underwent abdominal US, which revealed a 3 cm in size mass of the pancreatic head with hyperechoic spots. He had an episode of acute pancreatitis in the history, and since 1 year, he complained of a fever of unknown origin. The 18F-FDG PET-MRI confirmed the presence of a 2.9 cm mass in the pancreatic head, with an intense tracer uptake (SUVmax 4.8) (Fig. 3). Serum tumour markers were unremarkable. An Endoscopic US (EUS) with FNA-biopsy was also performed, and histology confirmed the suspect of SPN with a positive immunostaining for β-catenin. He underwent pancreatico-duodenectomy. Histology of the specimen showed a SPN without perivascular/perineural invasion. Mitotic index was 0–1/10 HPF, and immunostaining was positive for progesterone receptors, alpha-1-antichymotrypsin, alpha-1-antitrypsin and neuron-specific enolase. The patient developed a pancreatic biochemical leak in the post-operative course. He was alive without disease 25 months after surgery.

Clinical features and preoperative diagnosis

The three cases from our institution were included in the systematic review. Clinic-pathological features, surgical treatment and outcome are summarised in Table 2. There were 246 male patients with a pancreatic SPN, and mean age at presentation was 34.3 (range 4–78) years. Only 58 (26.2%) patients were younger than 18 years old. They mostly presented with abdominal pain or discomfort, but more than one-third (35.9%) were asymptomatic. The SPN was located in the body–tail region of the pancreas in 63.7% of cases, and mean tumour size was 6.3 (range 0.5–26) cm. Ten (4.1%) patients presented with distant (mostly liver) metastases. In 12 (5.5%) patients, pre-operative imaging studies included 18F-FDG PET-CT, and SPNs showed an intense tracer uptake in 80% of cases. In 40 (19.1%) patients, FNA was performed, resulting in a correct identification of SPNs in 82.5% of cases. When considered together, pre-operative imaging studies and cytopathological examination allowed a correct pre-operative diagnosis in 53.6% of patients, whereas other pancreatic neoplasms (i.e. ductal or acinar adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine neoplasm-NEN, unspecified pancreatic neoplasm), or a pseudocyst represented the alternative diagnoses leading the patients to surgery.

Surgical treatment and pathological features

The vast majority (97.2%) of patients underwent pancreatic resection. Surgery consisted mostly in standard pancreatic resections (pancreatico-duodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, and total pancreatectomy) performed in 90.4% of patients, and in 19 (9.6%) limited pancreatic resections (central pancreatectomy, duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection, and enucleation). Among 10 patients presenting with distant metastases, 2 patients had adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery, 2 patients underwent surgical resection only, and 3 patients received only chemotherapy (i.e. gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil) and/or trans-arterial embolization (TAE) of liver metastases; four of them died of disease after a mean follow-up of 6.7 months. Seventy-six studies reported on immunohistochemistry, excluding case series with aggregate male/female data. Beta-catenin resulted positive in all cases available, as well as CD56, while progesterone receptors were positive in 77.8% of cases.

Follow-up and outcome

Follow-up time data were available for 141 (57.3%) patients, and mean follow-up was 47.0 (range 4–180) months. Fourteen (7.2%) patients showed a disease recurrence, after a mean disease-free survival (DFS) of 43.1 (range 6–96) months after standard pancreatic resections. Six of them received a treatment, which consisted of various chemotherapy regimens (i.e. gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil, capecitabine, docetaxel, oxaliplatin, cisplatin, and irinotecan), in four patients associated with loco-regional treatments (i.e. TAE, microwave ablation, radiotherapy) or re-do surgery. Five of these patients were alive with disease after initial surgery (range 55–180 months). Patient outcome was reported in 200 (81.3%) cases, and most (89.5%) patients were alive without disease.

Discussion

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) of the pancreas is a rare neoplasm. It mainly affects young women, suggesting a role form hormonal factors, but no association with endocrine diseases has been reported so far [2]. Its natural history is still uncertain, especially in those rare SPNs that develop in male patients. This neoplasm may derive from genital ridge-related cells [13], or pluripotent stem cells of the genital ridges [14] that become attached to the primordial pancreas during embryogenesis. Moreover, extra-pancreatic SPNs have been reported in retropancreatic tissue, ovary, and testis [2]. A systematic review on SPNs by Law et al. [9] reported of 336 SPNs in men collected up to 2012 (12% of the whole cases), as from the experience of our institution, with 15.8% of males among all patients operated for a SPN in the last 30 years. The present systematic review comprised 1052 total SPNs, with a SPN rate in males of 23.4%, resulting higher than previously reported. However, this finding is due to the article selection process, which provided for the exclusion of series including female patients only.

In male patients, SPNs show an older age at presentation when compared with that in female patients [6, 15, 16]. In the present review, the oldest patient was 78 years old, and adult patients represented 73.8% of total SPNs in males (mean age, 42.2 years). The late occurrence of SPN in males might be the result of a long-term exposure of the ectopic ovarian like stroma to normal level of female sex hormones [16], since normal levels of both progesterone and estrogen were detected in male patients [16]. When comparing young (less than 18 years old) and adult male patients with SPNs, the former showed a slightly larger mean tumour size than the latter (7.0 cm vs. 5.7 cm), as Bender et al. reported of a mean SPN size of 8.2 cm in young patients [17]. Regarding tumour site, adult male patients showed a SPN located in the body–tail region of the pancreas in the majority (65.8%) of cases, whereas in young males, SPNs may be located in the pancreatic head and body–tail in 41.4% and 56.9% of cases, respectively. This finding may suggest that distal pancreatic lesions, which are less likely symptomatic, may be detected only later in life, irrespective of their time of onset.

The clinical presentation of SPN usually consists of non-specific symptoms (i.e. abdominal pain or abdominal discomfort), and patients may be even asymptomatic. The number of incidentally detected SPNs has grown, accounting for about 40% of all SPN cases (irrespective of gender) [9], and in our systematic review 35.9% of patients were asymptomatic at diagnosis. No tumour markers or routine laboratory parameters have been identified for the diagnosis of SPNs, thus pre-operative diagnosis is based on imaging studies and cytopathological examination of FNA samples. Pre-operative diagnosis of SPNs may be challenging, especially in male patients for whom this type of exocrine neoplasm is less often suspected. In these patients, the main alternative diagnosis may be a pancreatic NEN. The introduction of CT scan in the 1980s has increased the pre-operative diagnostic accuracy for SPNs. Ultrasound, CT scan and MRI typically show a large well-circumscribed, heterogeneous mass with varying solid and cystic components [18], demarcated by peripheral contrast enhancement corresponding to a fibrous pseudocapsule, and occasional calcifications. Recently, Wang et al. [19] reported that calcifications and enhanced solid components within the unenhanced cystic components (defined “floating cloud” sign) are useful features in discriminating SPNs from hypodense pancreatic NENs at CT scan [19].

In our systematic review, most of the patients underwent a CT scan, but an 18F-FDG PET-CT (or PET-MRI) was performed in only 12 (5.5%) patients. Although the intensity of 18F-FDG uptake in SPNs may vary widely due to tumour heterogeneity [20], in a previous study [21] we showed that only two (3%) out of 69 SPNs collected in the literature were PET negative. Some authors compared the CT [22,23,24] and MRI [25] imaging features of pancreatic SPNs between male and female patients. Males were significantly older than female patients, and irrespective of tumour size, SPN in males had mainly a solid component, whereas female patients had a significantly high rate of cystic lesions. The high metabolism of SPNs at FDG-PET seems to have a direct relationship with tumour cellularity [26] and with the solid (cellular) component of SPNs [26], irrespective to malignant behaviour. Thus, SPNs with a predominant solid component, as those detected in males, can be easily identified based on a marked avidity for 18F-FDG (SUVmax range 3.5–18.3) [27], and differentiated from pancreatic NENs, which usually have a poor 18F-FDG uptake and a low SUVmax value [27]. In the present review, SPNs showed an intense tracer uptake at FDG-PET in 80% of cases (mean SUVmax 5.0). In the presence of a pancreatic mass suspected for a SPN or a NEN, even in case of liver metastases, surgery would be the treatment of choice. However, a correct diagnosis may be crucial in patients not fit for surgery, giving them the chance of a correct alternative treatment (i.e. somatostatin analogues for NENs).

Some authors [28] stated that radiologic diagnosis is sufficient for SPNs, especially when planning surgery. However, obtaining a pre-operative histologic diagnosis may be sometimes advisable, and EUS-guided FNA is the most frequently used procedure and a valuable technique for its diagnostic accuracy [29,30,31]. In the present review, when considered together imaging studies and FNA allowed a correct pre-operative diagnosis in 53.6% of cases. Notably, only 40 (19.1%) patients underwent a pre-operative FNA, which resulted positive for SPN in 82.5% of cases. Since a low amount of material may be available through FNA and immunohistochemistry is mandatory for diagnosis, the correct diagnostic antibody panel should be accurately chosen [32]. In young patients, FNA may not differentiate between SPN and pancreatoblastoma [33], whereas in adults a misdiagnosis with a pancreatic NEN may be avoided detecting the highly specific patterns of E-cadherin and β-catenin staining [34].

Histologically, SPNs are characterised by solid areas alternated with a pseudopapillary pattern and cystic spaces. These features result from degenerative changes occurring in the solid neoplasm [35], without increased mitoses or cytological atypia [36, 37]. These neoplasms always show expression of β-catenin, thus positive nuclear and cytoplasmic staining for β-catenin are now considered essential diagnostic criteria [2]. Immunoreactivity for cytokeratins, synaptophysin, and CD56 can be observed in 30% to 70% of cases, whereas chromogranin is usually negative [2]. The tumour cells also express vimentin, CD10, CD99, CD56, alpha1-antitrypsin, and progesterone receptors [2]. In the present review, β-catenin was always positive when performed, whereas progesterone receptors were detected in 77.8% of cases. Tien et al. [38] found no difference in immunostaining for sex hormone-receptor proteins, or in pathological features when stratified for gender.

In the present review, 206 (97.2%) patients underwent surgery, which consisted in standard pancreatic resections in 90.4% of cases. Tumour enucleation and incomplete excision should be avoided, due to the risk of tumour dissemination and a high recurrence rate [18]. Some authors proposed extended and more radical surgery in men with SPNs, due to the high likelihood of aggressive disease [15], but no significant differences in terms of follow-up outcomes have been demonstrated between male and female patients [39]. Surgery continues to be considered the standard of care for localised SPNs, and it is accepted for metastatic disease [40]. In the present review, among 10 patients who presented with distant (mostly liver) metastases, four patients underwent surgery of the primary SPN, and two of them were still alive with disease 29 and 70 months after surgery, respectively.

No established chemotherapy regimen is currently recommended for SPNs, but in case of metastatic disease, combined systemic and loco-regional treatments may be used with a palliative intent. Among 10 patients presenting with distant metastases, seven received a combined treatment (i.e. resective or palliative surgery, chemotherapy, and/or TAE), and three of them died of disease after a mean follow-up of 12 months. Concerning 14 patients with disease recurrence (mean DFS 43.1 months), six received a combined treatment (i.e. chemotherapy, TAE, radiotherapy, and/or re-do surgery), and five of them were alive with disease up to 180 months after surgery. Aggressive SPNs (defined as SPNs that locally invaded, recurred, or metastasised) showed a 5- and 10-year survival rate of 71.1% and 65.5%, respectively [41].

To date, a standardised follow-up protocol is not available, but a long follow-up should be performed as SPN recurrence may occur even 10 years after resection [42]. In our review, 14 (7.2%) patients showed a disease recurrence (i.e. liver, or peritoneum), after a mean DFS of 43.1 months (up to 96 months) after surgery. The vast majority (89.5%) of patients were alive with no evidence of disease after a mean follow-up of 47 (range 4–180) months. This finding confirms that SPNs may have an excellent prognosis after radical surgery [18].

Limitations of this systematic review include the variation in the extent and quality of variables collected. Moreover, many institutional series presenting aggregate data of female and male patients had to be excluded from the present review.

In conclusion, pancreatic SPN in males occur mainly (73.8%) in adult patients rather than in childhood. In case of detection of a solid-cystic pancreatic mass, a diagnosis of SPN should be taken in account even in asymptomatic males with a large tumour size. Cytopathologic examination may help the therapeutic planning, particularly in case of metastatic or non-resectable disease. A high hypermetabolism at 18F-FDG PET (CT or MRI) strongly suggests a SPN in the differential diagnosis with a pancreatic NEN. Surgery is the treatment of choice in pancreatic SPN, and a long disease-free survival up to 180 months may be achieved after radical resection. In metastatic setting, a multimodal treatment may provide a long-term survival up to 70 months.

References

Frantz VK (1959) Tumors of the pancreas. In: Bumberg CW (ed) Atlas of tumor pathology. US Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, pp 32–33

Klöppel G, Basturk O, Klimstra DS, Lam AK, Notohara K (2019) Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. In: Carneiro F, Chan JKC, Cheung NYA (eds) Digestive system tumours. WHO classification of tumors. IARC Press, Lyon, pp 340–342

Adams AL, Siegal GP, Jhala NC (2008) Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a review of salient clinical and pathological features. AdvAnatPathol 15:39–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAP.0b013e31815e5237

Papavramidis T, Papavramidis S (2005) Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: review of 718 patients reported in English literature. J Am CollSurg 200:965–972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.02.011

Tang LH, Aydin H, Brennan MF, Klimstra DS (2005) Clinically aggressive solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: a report of two cases with components of undifferentiated carcinoma and a comparative clinicopathologic analysis of 34 conventional cases. Am J SurgPathol 29:512–519. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pas.0000155159.28530.88

Hruban RH, Pitman MB, Klimstra DS (2007) Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms. In: Hruban RH, Pitman MB, Klimstra DS (eds) Atlas of tumor pathology, series 4: tumors of the pancreas. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, pp 231–250

Estrella JS, Li L, Rashid A, Wang H, Katz MH, Fleming JB, Abbruzzese JL, Wang H (2014) Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: clinicopathologic and survival analyses of 64 cases from a single institution. Am J SurgPathol 38:147–157. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000141

Jutric Z, Rozenfeld Y, Grendar J, Hammill CW, Cassera MA, Newell PH, Hansen PD, Wolf RF (2017) Analysis of 340 patients with solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: a closer look at patients with metastatic disease. Ann SurgOncol 24:2015–2022. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-5772-z

Law JK, Ahmed A, Singh VK, Akshintala VS, Olson MT, Raman SP, Ali SZ, Fishman EK, Kamel I, Canto MI, Dal Molin M, Moran RA, Khashab MA, Ahuja N, Goggins M, Hruban RH, Wolfgang CL, Lennon AM (2014) A systematic review of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms: are these rare lesions? Pancreas 43:331–337. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0000000000000061

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2010) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 8:336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007

Lingg G, Nebel G, Angelkort A, Klöppel G (1981) Computed tomography in a new type of acinar cell tumour of the pancreas: the solid acinar cell tumour with cystic degeneration. Eur J Radiol 1:232–235

Klöppel G, Morohoshi T, John HD, Oehmichen W, Opitz K, Angelkort A, Lietz H, Rückert K (1981) Solid and cystic acinar cell tumour of the pancreas. A tumour in young women with favourable prognosis. Virchows Arch APatholAnatHistol 392:171–183

Kosmahl M, Seada LS, Jänig U, Harms D, Klöppel G (2000) Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: its origin revisited. Virchows Arch 436:473–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004280050475

Terris B, Cavard C (2014) Diagnosis and molecular aspects of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas. SeminDiagnPathol 31:484–490. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semdp.2014.08.010

Machado MC, Machado MA, Bacchella T, Jukemura J, Almeida JL, Cunha JE (2008) Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: distinct patterns of onset, diagnosis, and prognosis for male versus female patients. Surgery 143:29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2007.07.030

Regi P, Salvia R, Cena C, Girelli R, Frigerio I, Bassi C (2013) Cystic “feminine” pancreatic neoplasms in men. Do any clinical alterations correlate with these uncommon entities? Int J Surg 11:157–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.12.008

Bender AM, Thompson ED, Hackam DJ, Cameron JL, Rhee DS (2018) Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas in a young pediatric patient: a case report and systematic review of the literature. Pancreas 47:1364–1368. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0000000000001183

Vassos N, Agaimy A, Klein P, Hohenberger W, Croner RS (2013) Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) of the pancreas: case series and literature review on an enigmatic entity. Int J ClinExpPathol 6:1051–1059

Wang C, Cui W, Wang J, Chen X, Tong H, Wang Z (2019) Differentiation between solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas and hypovascular pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors by using computed tomography. ActaRadiol 60:1216–1223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0284185118823343

Park M, Hwang HK, Yun M, Lee WJ, Kim H, Kang CM (2018) Metabolic characteristics of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: their relationships with high intensity (18)F-FDG PET images. Oncotarget 9:12009–12019. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.23846

Milanetto AC, Liço V, Zoccarato F, Bissoli S, Pedrazzoli S, Pasquali C (2016) 18F-FDG PET-CT in cystic tumors of the pancreas. J Cancer Res Updates 5:12–18

Hu S, Huang W, Lin X, Wang Y, Chen KM, Chai W (2014) Solid pseudopapillarytumour of the pancreas: distinct patterns of computed tomography manifestation for male versus female patients. Radiol Med 119:83–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11547-013-0327-2

Park MJ, Lee JH, Kim JK, Kim YC, Park MS, Yu JS, Kim YB, Lee D (2014) Multidetector CT imaging features of solid pseudopapillarytumours of the pancreas in male patients: distinctive imaging features with female patients. Br J Radiol 87:20130513. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20130513

Shi S, Zhou Y, Hu C (2019) Clinical manifestations and multi-slice computed tomography characteristics of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas between males and females. BMC Med Imaging 19(1):87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-019-0390-9

Sur YK, Lee JH, Kim JK, Park MJ, Kim B, Park MS, Choi JY, Kim YB, Lee D (2015) Comparison of MR imaging features of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of pancreas between male and female patients. Eur J Radiol 84:2065–2070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.07.025

Dong A, Wang Y, Dong H, Zhang J, Cheng C, Zuo C (2013) FDG PET/CT findings of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas with CT and MRI correlation. ClinNucl Med 38:e118-124. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0b013e318270868a

Guan ZW, Xu BX, Wang RM, Sun L, Tian JH (2013) Hyperaccumulation of 18F-FDG in order to differentiate solid pseudopapillary tumors from adenocarcinomas and from neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors and review of the literature. Hellen J Nucl Med 16:97–102. https://doi.org/10.1967/s002449910084

Kim CW, Han DJ, Kim J, Kim YH, Park JB, Kim SC (2011) Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: can malignancy be predicted? Surgery 149:625–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2010.11.005

Song JS, Yoo CW, Kwon Y, Hong EK (2012) Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm: three case reports with review of literature. Korean J Pathol 46:399–406. https://doi.org/10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2012.46.4.399

Jani N, Dewitt J, Eloubeidi M, Varadarajulu S, Appalaneni V, Hoffman B, Brugge W, Lee K, Khalid A, McGrath K (2008) Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: a multicenter experience. Endoscopy 40:200–203. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-995364

Roskell DE, Buley ID (2004) Fine needle aspiration cytology in cancer diagnosis. BMJ 329:244–245. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7460.244

La Rosa S, Bongiovanni M (2019) Pancreatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm: key pathologic and genetic features. Arch Pathol Lab Med. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2019-0473-RA

Raffel A, Cupisti K, Krausch M, Braunstein S, Trobs B, Goretzki PE, Willnow U (2004) Therapeutic strategy of papillary cystic and solid neoplasm (PCSN): a rare non-endocrine tumor of the pancreas in children. SurgOncol 13:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2003.09.003

Burford H, Baloch Z, Liu X, Jhala D, Siegal GP, Jhala N (2009) E-cadherin/beta-catenin and CD10: a limited immunohistochemical panel to distinguish pancreatic endocrine neoplasm from solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspirates of the pancreas. Am J ClinPathol 132:831–839. https://doi.org/10.1309/AJCPVT8FCLFDTZWI

Santini D, Poli F, Lega S (2006) Solid-papillary tumors of the pancreas: histopathology. J Pancreas 7:131–136

Geers C, Moulin P, Gigot JF, Weynand B, Deprez P, Rahier J, Sempoux C (2006) Solid and pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas-review and new insights into pathogenesis. Am J SurgPathol 30:1243–1249. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pas.0000213311.28682.b2

Matos JM, Grützmann R, Agaram NP, Saeger HD, Kumar HR, Lillemoe KD, Schmidt CM (2009) Solid pseudopapillary tumor neoplasms of the pancreas: a multi-institutional study of 21 patients. J Surg Res 157:137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2009.03.091

Tien YW, Ser KH, Hu RH, Lee CY, Jeng YM, Lee PH (2005) Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: is there a pathologic basis for the observed gender differences in incidence? Surgery 137:591–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2005.01.015

Cai YQ, Xie SM, Ran X, Wang X, Mai G, Liu XB (2014) Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas in male patients: report of 16 cases. World J Gastroenterol 20:6939–6945. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6939

El Nakeeb A, Abdel Wahab M, Elkashef WF, Azer M, Kandil T (2013) Solid pseudopapillarytumour of the pancreas: incidence, prognosis and outcome of surgery (single centre experience). Int J Surg 11:447–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.04.009

Hao EIU, Hwang HK, Yoon DS, Lee WJ, Kang CM (2018) Aggressiveness of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. A literature review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 97:e13147. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000013147

Tjaden C, Hassenpflug M, Hinz U, Klaiber U, Klauss M, Büchler M, Hackert T (2019) Outcome and prognosis after pancreatectomy in patients with solid pseudopapillary neoplasms. Pancreatology 19:699–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pan.2019.06.008

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Padova within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: PC, MAC. Literature search and acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data: MAC, ML, GZAL, DA. Drafting of the manuscript: MAC, ML. Critical revision of the manuscript: PC.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Milanetto, A., Gais Zürcher, AL., Macchi, L. et al. Pancreatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm in male patients: systematic review with three new cases. Updates Surg 73, 1285–1295 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-020-00905-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-020-00905-4