Abstract

Neonatal diabetes mellitus is a rare disorder of glucose metabolism with onset within the first 6 months of life. The initial treatment is based on insulin infusion. The technologies for diabetes treatment can be very helpful, even if guidelines are still lacking. The current study aimed to provide a comprehensive review of the literature about the safety and efficacy of insulin treatment with technology for diabetes to support clinicians in the management of infants with neonatal diabetes mellitus. A total of 22 papers were included, most of them case reports or case series. The first infants with neonatal diabetes mellitus treated with insulin pumps were described nearly two decades ago. Over the years, continuous glucose monitoring systems were added to treat these individuals, allowing for a better customization of insulin administration. Insulin was diluted in some cases to further minimize the doses. Improvement in technology for diabetes prompted clinicians to use new devices and algorithms for insulin delivery in infants with neonatal diabetes as well. These systems are safe and effective, may shorten hospital stay, and help clinicians weaning insulin during the remission phase in the transient forms or switching from insulin to sulfonylurea when suggested by the molecular diagnosis. New technologies for insulin delivery in infants with neonatal diabetes can be used safely and closed-loop algorithms can work properly in these situations, optimizing blood glucose control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Technology for insulin delivery in individuals with diabetes is suggested irrespective of age. |

Insulin pumps, and more recently automated insulin delivery systems, are safe and effective even in infants with neonatal diabetes mellitus. |

Technologies for insulin delivery may shorten hospital stay and support clinicians in insulin dosing and in switching from insulin to oral hypoglycemic agents when suggested. |

Automated insulin delivery systems with closed-loop algorithms can be the gold standard for treating infants with neonatal diabetes mellitus. |

Introduction

Neonatal diabetes mellitus (NDM) is a rare disease defined by the presence of severe hyperglycemia requiring treatment mainly before 6 months of age and less frequently between 6 months and 1 year [1]. NDM incidence is between 1:21,000 and 1:350,000 live births, with the highest incidence in those countries with high rates of consanguinity [2,3,4,5]. It can be classified into transient NDM (TNDM) and permanent NDM (PNDM) [6, 7] and insulin therapy must be started if necessary. Genetic testing is suggested in all patients and a switch from insulin to sulfonylureas is recommended for carriers of KCNJ11 and ABCC8 abnormalities [1, 8, 9].

Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) should be taken into consideration in these patients, as it permits the administration of very small insulin doses and avoids severe hypoglycemic episodes due to the unpredictable feeding patterns of neonates [10, 11]. Technology for insulin delivery is recommended and appropriate for youth with diabetes, regardless of age. Indeed, standard insulin pump therapy is recommended for all youth with diabetes if access to more advanced diabetes technologies, including sensor-augmented pump therapy (SAP), low glucose suspend (LGS) or predicted low glucose suspend (PLGS) system, and automated insulin delivery (AID), is limited [12].

This paper presents a systematic review of the significant literature on the use of technology for insulin treatment in patients with NDM.

Materials and Methods

The literature search was carried out according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13] and provides a review of the current literature about technologies for insulin delivery in the management of NDM. The search for eligible studies was performed from inception to 20 July 2024 in the PubMed database. The keywords used for the query strings were “Neonatal diabetes mellitus” AND “insulin pump” and “Neonatal diabetes mellitus” AND “Closed loop”. Only “insulin pump” is indexed in the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) thesaurus, while “Neonatal diabetes mellitus” is indexed as supplementary concept in association with other terms (permanent, hypothyroidism, and so on).

Non-English language papers were excluded. To be as comprehensive as possible, only guidelines and review papers were not included in the Literature Review section. Commentaries and editorials were taken into consideration only if they reported original data. Additional studies were searched from the reference lists of the selected papers. The literature search was carried out by two authors (R.P. and V.C.) and identified 162 manuscripts with the first query string and 23 with the second. Once the criteria had been applied, most of them were excluded for not meeting the predefined criteria and 25 papers were selected from the first search. Only 1 paper was added from the second search, and thus 26 papers were retrieved to assess for eligibility, five articles were excluded either for not meeting the prespecified study treatment or due to the inconsistency of the study population (i.e., other than neonates). Thus, 21 articles were elected for this review and underwent a review of the full text (PRISMA flowchart; Fig. 1). One additional paper was added because it reported the insulin treatment of an infant with NDM with advanced hybrid closed loop (AHCL) even if not retrieved by the literature search [14]. A final number of 22 papers were included in this review paper. The papers were considered irrespective of study setting (hospital or home), subtype of NDM, duration of insulin requirement, and genetic defect. The Population, Intervention, Professions, Outcomes and Healthcare system (PIPOH) summary of this review is presented in Table 1.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Data regarding the treatment of NDM with technologies for diabetes are available from observational studies, case reports, and case series. The main features of selected studies are summarized in Table 2.

The first description of treatment with CSII in an individual with NDM was done by Olinder et al. [15]. They reported on two infants with NDM who were treated with CSII (Minimed 507C and 508 and a Disetronic H-tron V100). No episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis, severe hypoglycemia, and technical issues were reported. Diluted Lispro insulin (10 IU/mL) was used in the infusion sets. The authors concluded that CSII was effective and safe, suggesting that it could be an alternative treatment for these individuals. The same conclusion was drawn by Park et al. [16], who treated an infant with TNDM and showed wide serum glucose fluctuation. Both groups suggested that CSII may shorten the length of hospital stays in these children. In addition to the evidence about safety and effectiveness, Tubiana-Rufi [17] described her experience over 18 years with 17 children and adolescents (8 with PNDM). She confirmed previous data and showed that CSII allows for easy adaptation of insulin dosing, more flexible based on the current feeding regimen. She suggested that very small insulin doses could be administered after insulin dilution (5–10 IU/ml).

Interestingly, Ortolani et al. [18] described the first infant with NDM treated with CSII integrated with a continuous glucose monitoring system (CGMS). In their paper, they described three patients with PNDM due to INS gene mutation, all of them treated with CSII. Insulin was not diluted, and the authors stated that both treatment strategies are feasible and safe not only in the hospital setting, but also at home. Moreover, they suggest that CSII–CGM integrated system may be superior to CSII only. The same conclusion was achieved with the use of the MiniMed 530G system, the first-generation artificial pancreas system, which allowed for fine insulin dosing with automation algorithms preventing hypoglycemia [19]. In contrast, in addition to the advantage of CSII, the CGM system could be also technically difficult, as reported in a 6q24-related TNMD with severe intrauterine growth retardation [20].

The postnatal growth and HbA1c levels in NDM were evaluated by Alyafie et al. [21] in five patients treated with a pump and in four patients treated with multiple daily injections (MDI). Even if no statistical significance was reached, the authors suggest that insulin pumps could be associated with better glucose control and catch-up growth at 24 months of age.

A Swedish study reported data from six neonates with TNDM treated with an insulin pump (Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm Real-Time and Paradigm VEO) from day of life 5–54 to day of life 17–145 [22]. The authors diluted insulin 1:10 (final concentration 10 IU/ml) as described by the manufacturer. The meal boluses represented 70–80% of the total daily dose of insulin and they were personalized for each patient on the basis of CGM values and amount of milk. The authors concluded that these devices are safe for neonates with NDM and effective in improving blood glucose control. However, they suggested that the staff should have good technical skills to use this technology properly. Support for the staff involved in NDM management comes from the video and the paper by Zanfardino et al. [23, 24], who reported technical information about the management of the insulin pump infusion set in these patients who usually present low birth weight and scarce subcutaneous adipose tissue.

A few different and interesting clinical aspects are pointed out in some case reports. Passanisi et al. concluded that both insulin pumps and long-acting insulin injections alone are effective, but proper expertise is mandatory [25]. The use of an insulin pump was reported also in very rare situations such as homozygous PTF1A enhancer mutation (two neonates) [26], GLIS3 mutation (two twins) [27], and Donohue syndrome [28]. Interestingly, Huggard et al. suggested that the decision to start an insulin pump in NDM should be shared with caregivers. Even though their patient died at 4 months, the patient’s mother declared her satisfaction with the choice of CSII with a sensor-augmented pump, since it protected her son from hyper- and hypoglycemia and improved his quality of life [28]. An insulin pump was also very helpful for two patients who switched to sulfonylurea after genetic testing, allowing for a safe and progressive decrease in the daily insulin infusion together with the introduction of sulfonylurea [29]. In all these papers, the authors confirmed that insulin pumps, with or without CGM, are safe and effective in blood glucose management.

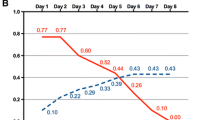

Consistent support to start insulin pumps in neonates with NDM is provided by Kapellen et al. [11]. In their large cohort of 67 neonates treated with a pump, they report data about the insulin requirement, but no information about gene mutation and transient/permanent form is provided. The median insulin dose at pump start was 0.74 IU/kg (median age 1.8 weeks), with a median basal insulin requirement of 0.56 IU/kg and a median requirement of pre-meal insulin of 0.4 IU/10 g of carbohydrates (I:C ratio 1:25 IU/g of CHO). The dose was adjusted on the basis of blood glucose values, and it was 0.64 IU/kg at discharge (basal insulin requirement 0.43 IU/kg in 63 patients). At the follow-up visit, 35 weeks later, the median insulin requirement was 0.52 IU/kg (median basal insulin requirement was 0.38 IU/kg in 51 patients). The median age at follow-up visit (44 weeks) suggests that most of them had a PNDM. Some data about insulin requirements had been reported previously, but the cohorts were small.

Sensor-augmented pump (SAP) therapy with the MiniMed™ 640G system was described in three patients [30]. The SmartGuard Technology embedded in this system was reported as particularly useful for these infants to prevent hypoglycemia, to manage insulin delivery more accurately, and to reduce the burden of diabetes for the caregivers. Confirmatory data were shown by Sakai et al. in a small for gestational age infant with TNDM [31]. He was treated with continuous intravenous insulin infusion initiated on day of life 4. At 39 days, SAP was started successfully without any hypoglycemia. After discontinuation of insulin at 58 days of age, the infant was discharged. The authors suggested that CGM may help physicians to decide when discontinue insulin in SAP therapy.

The usefulness of patient monitoring technologies was described in a proband with NDM due to the beta cell potassium ATP channel gene KCNJ11 mutation. CGM and insulin pumps with automated insulin delivery (AID) and remote monitoring technologies allowed for an easy switch from insulin to oral sulfonylurea [32]. This report further supports the safety and effectiveness of technologies for infants with diabetes. Similar data and conclusions about switching from insulin to sulfonylurea under CGM were reported in two cases by Mancioppi et al. [33]. They described a 51-day-old infant started on CSII therapy (MiniMedTM 780G) and CGM (Guardian Sensor 4) with only PLGS function on. Insulin dilution was not necessary. After the detection of a de novo heterozygous pathogenic mutation in the KCNJ11 gene, insulin administration was safely and progressively reduced, with a simultaneous switch to glibenclamide. The safety and effectiveness of AID systems in infants with NDM were also confirmed by Wanaguru et al. [34]. In their case series of four patients younger than 2 years of age, one infant was genetically confirmed to have 6q24 TND on day of life 23. Due to a very low insulin dose (0.8 IU/day), he commenced on AHCL with SmartGuard technology (blood glucose target 6.7 mmol/l with 0.9% normal saline and auto-corrections turned on) on day of life 26 with 1:10 diluted Aspart, and after 18 days he went into complete remission. We reported similar findings in an infant with 6q24-related TNDM treated. He started on MiniMed™ 780G and CGM with only PLGS function on and insulin Lispro 100 IU/ml. The patient was discharged home, he did not experience any hypoglycemia, and discontinued insulin treatment safely when he went into remission [14].

Discussion

NDM is a heterogeneous rare disease. Treatment may be very challenging because of the rarity of the disorder, small insulin doses, and unpredictable feeding. The development of technologies for diabetes treatment provided useful tools for clinicians involved in diabetes care management. Gene mutations can be detected in more than 80% of individuals with NDM [1, 35], less frequently in preterm (66%) than in full-term neonates (83%) [36], prompting the physician to try sulfonylurea in most cases, but even in this situation the first-line treatment remains insulin infusion. The lack of genetic testing is a good point to not try sulfonylurea treatment [1]. At hyperglycemia onset, a differential diagnosis with other causes of neonatal hyperglycemia, such as infection, low birth weight, beta-cell immaturity, parental nutrition, and hypoxia, may be very challenging overall in preterm babies, and a short course of insulin treatment may be required. If hyperglycemia disappears after a few days, NDM can be reasonably excluded from the diagnostic workup. While waiting for genetic testing results, insulin treatment is necessary to normalize blood glucose as much as possible and to allow for appropriate development and weight growth. The remission rate in newborns with TNDM is close to 100% and insulin therapy may be unnecessary if hyperglycemia is mild. On the contrary, if the initial presentation is severe, insulin treatment has to be promptly started and optimized. In infants with PNDM, the initial insulin treatment can be switched to sulfonylurea tablets once sulfonylurea-responsive KCNJ11 or ABCC8 mutations are determined, since sulfonylurea therapy may be critical to improving long-term neurocognitive and neuromuscular outcomes [37]. Management of intravenous infusion can be complicated by infections and displacement, and thus CSII may also be a plausible alternative way to manage newborns with the lowest birth weight. Data from the literature suggest that these devices allow for safer and earlier discharge of infants to home [15, 16]. There are no clinical research studies aiming to evaluate the best way to deliver insulin to infants with NDM and optimal setting. Reasonably, such trials will never be run in consideration of clinical and genetic heterogeneity, and thus our knowledge about the optimal treatment of these individuals is based on case reports and observational studies.

Given the rarity of the condition, awareness and clinical practice of such conditions can be limited, and thus a review reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesize findings from available studies. The difficulties in the management and treatment of NMD were pointed out by a recent survey of pediatricians practicing in the Arab Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes (ASPED) countries. This survey highlighted that almost all participants (93%) start insulin treatment, preferably after dilution (80%). Interestingly, basal-bolus and insulin pumps were used similarly (36% each), suggesting that the insulin pump was not the most preferred route of administration. The authors concluded that established guidelines for this condition are needed, in consideration of the inhomogeneous treatment despite the good knowledge of this condition [38]. A similar survey was recently closed by the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, and we hope that the results will be helpful for future treatment.

The advances in technology for diabetes treatment give physicians a wide range of devices and clinically relevant solutions to treat patients. The first reports about treatment with CSII in infants with NDM showed that this route of administration was safe [15,16,17]. As these papers are case reports or case series, the only data that aimed to provide clinically useful information to set the insulin pump were reported by Kapellen et al. from 67 infants with NDM [11]. They reported detailed information about insulin dose and treatment management irrespective of genetic diagnosis and clinical course, unfortunately.

A significant step toward the improvement of care was represented by the integration of CSII with CGMS [18,19,20, 29], which is helpful to avoid hypoglycemia episodes [39]. Despite technical difficulties and lack of randomized trials investigating the real benefits, the CGMS allows for 24-h monitoring with retrospective or real-time evaluation of glucose levels, avoiding blood samplings, and thus fine dosing of insulin and reduction of blood glucose fluctuations [40].

Over the last decade, technology for diabetes treatment has been greatly improved and AID systems have become more widely available [12]. In the case of very low doses, insulin dilution may be helpful in administering minimal insulin doses [18, 20, 25] and allowing the AID systems to work in automode [34]. The use of AID systems with automode function has been reported in some infants more recently [30, 31, 33, 34]. In all these papers, AHCL technology is feasible and safe, allowing for optimization of blood glucose control, early discharge of the patient to home, and supporting the clinicians both in switching from insulin to sulfonylurea and in weaning insulin during the transition to complete remission in infants with TNDM. Despite promising results, delivery of very small doses of insulin in a neonate with NDM and intrauterine growth retardation may be very challenging, and the insertion of needles for insulin infusion and glucose sensing may appear very difficult or nearly impossible. However, it should be noted that the last generation of AID systems cannot be prescribed in infants below 1 year of age and most of them cannot be used under the age of 7. Furthermore, available data suggest that technologies for insulin delivery in infants with NDM can face successfully all the critical points in clinical management, and practical suggestions to manage the infusion sites are provided to support the staff in the management of the devices [23, 24]. Furthermore, the use of an AHCL system has the pros of a lower number of injections to deliver the daily insulin. Technology for diabetes treatment allows normal feeding with normal growth [15, 16, 31], even in newborns with severe intrauterine growth retardation [17]. Finally, unanimously, these devices allow for shortened stay in the hospital, discharging the infants in safe conditions home [14, 15, 17].

This paper has some limitations. First, selected papers are not homogeneous regarding the clinical course, molecular diagnosis, and devices. Second, almost all papers are case reports or case series and there is a limited number of infants. The current study presents data as clearly as possible to provide clinicians useful data for clinical practice. We cannot exclude that some papers could have been missed through our search strategy because of inappropriate keywords. However, the literature on the topic is limited, and retrieving possible papers by reading the references of each paper reduces this bias as much as possible. Finally, we think that the quality of the evidence is quite poor in most of the papers, as the metabolic outcomes are incomplete in most of them, the AID device is often not specified, and the diluent used with the insulin is often not reported.

In conclusion, the evidence from the current study suggests that AID systems with AHCL technology are helpful for the treatment of infants with NDM. Even in preterm and low birth weight infants, CGMS and insulin catheters can be inserted safely. Treatment goals should be defined with the family members or caregivers for a therapeutic alliance that can be the key to treatment success. The staff of the diabetes team and/or the neonatal intensive care unit should have good technical skills to use this technology properly. AID systems can be used to treat these infants, reducing blood glucose fluctuations and preventing hypoglycemia. In the case of a total daily dose lower than the minimal requirement for the AHCL algorithm, insulin can be diluted to start the automode functionality, otherwise, the algorithm can properly work with the PLGS function on.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Greeley SAW, Polak M, Njølstad PR, Barbetti F, Williams R, Castano L, Raile K, Chi DV, Habeb A, Hattersley AT, Codner E. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: the diagnosis and management of monogenic diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2022;23(8):1188–211.

Habeb AM, Flanagan SE, Deeb A, et al. Permanent neonatal diabetes: different etiology in Arabs compared to Europeans. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:721–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-301744.

Al-Khawaga S, Mohammed I, Saraswathi S, Haris B, Hasnah R, Saeed A, Almabrazi H, Syed N, Jithesh P, El Awwa A, Khalifa A, AlKhalaf F, Petrovski G, Abdelalim EM, Hussain K. The clinical and genetic characteristics of permanent neonatal diabetes (PNDM) in the state of Qatar. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7(10): e00753. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.753.

Iafusco D, Massa O, Pasquino B, et al. Minimal incidence of neonatal/infancy onset diabetes in Italy is 1:90,000 live births. Acta Diabetol. 2012;49:405–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-011-0331-8.

Delvecchio M, Ortolani F, Rutigliano A, Vendemiale M, Piccinno E. Epidemiology. In: Neonatal and early onset diabetes mellitus. Cham: Springer; 2023. p. 23–38.

Barbetti F, Mammì C, Liu M, Grasso V, Arvan P, Remedi M, Nichols C. Neonatal diabetes: permanent neonatal diabetes and transient neonatal diabetes. In: Barbetti F, Ghizzoni L, Guaraldi F, editors. Frontiers in diabetes diabetes associated with single gene defects and chromosomal abnormalities. Karger Publishers AG; 2017. p. 1–25.

Busiah K, Drunat S, Vaivre-Douret L, et al. Neuropsychological dysfunction and developmental defects associated with genetic changes in infants with neonatal diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study [corrected]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1(3):199–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70059-7.

Bowman P, Sulen Å, Barbetti F, Beltrand J, Svalastoga P, Codner E, Tessmann EH, Juliusson PB, Skrivarhaug T, Pearson ER, Flanagan SE, Babiker T, Thomas NJ, Shepherd MH, Ellard S, Klimes I, Szopa M, Polak M, Iafusco D, Hattersley AT, Njølstad PR, Neonatal Diabetes International Collaborative Group. Effectiveness and safety of long-term treatment with sulfonylureas in patients with neonatal diabetes due to KCNJ11 mutations: an international cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(8):637–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30106-2.

Bowman P, Mathews F, Barbetti F, Shepherd MH, Sanchez J, Piccini B, Beltrand J, Letourneau-Freiberg LR, Polak M, Greeley SAW, Rawlins E, Babiker T, Thomas NJ, De Franco E, Ellard S, Flanagan SE, Hattersley AT, Neonatal Diabetes International Collaborative Group. Long-term follow-up of glycemic and neurological outcomes in an International Series of Patients With Sulfonylurea-Treated ABCC8 permanent neonatal diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(1):35–42. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-1520.

Rabbone I, Barbetti F, Gentilella R, et al. Insulin therapy in neonatal diabetes mellitus: a review of the literature. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;129:126–35.

Kapellen TM, Heidtmann B, Lilienthal E, et al. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion in neonates and infants below 1 year: analysis of initial bolus and basal rate based on the experiences from the German Working Group for Pediatric Pump Treatment. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17:872–9.

Sherr JL, Schoelwer M, Dos Santos TJ, Reddy L, Biester T, Galderisi A, van Dyk JC, Hilliard ME, Berget C, DiMeglio LA. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: diabetes technologies: insulin delivery. Pediatr Diabetes. 2022;23(8):1406–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.13421.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339: b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700.

Delvecchio M, Panza R, Schettini F, Piccinno E, Laforgia N. Safety and effectiveness of Medtronic MiniMed™ 780G in a neonate with transient neonatal diabetes mellitus: a case report. Acta Diabetol. 2024;61(4):529–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-023-02212-x.

Olinder AL, Kernell A, Smide B. Treatment with CSII in two infants with neonatal diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Diabetes. 2006;7:284–8.

Park JH, Kang JH, Lee KH, Kim NH, Yoo HW, Lee DY, Yoo EG. Insulin pump therapy in transient neonatal diabetes mellitus. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2013;18:148–51.

Tubiana-Rufi N. Insulin pump therapy in neonatal diabetes. Endocr Dev. 2007;12:67–74.

Ortolani F, Piccinno E, Grasso V, Papadia F, Panzeca R, Cortese C, Felappi B, Tummolo A, Vendemiale M, Barbetti F. Diabetes associated with dominant insulin gene mutations: outcome of 24-month, sensor-augmented insulin pump treatment. Acta Diabetol. 2016;53:499.

Marin MT, Coffey ML, Beck JK, Dasari PS, Allen R, Krishnan S. A novel approach to the management of neonatal diabetes using sensor-augmented insulin pump therapy with threshold suspend technology at diagnosis. Diabetes Spectr. 2016;29:176–9.

Fudvoye J, Farhat K, De Halleux V, Nicolescu CR. 6q24 transient neonatal diabetes—how to manage while waiting for genetic results. Front Pediatr. 2016;17(4):124. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2016.00124.

Alyafie F, Soliman AT, Sabt A, Elawwa A, Alkhalaf F, Alzyoud M, De Sanctis V. Postnatal growth of Infants with neonatal diabetes: insulin pump (CSII) versus Multiple Daily Injection (MDI) therapy. Acta Biomed. 2019;90:28–35.

Torbjörnsdotter T, Marosvari-Barna E, Henckel E, Corrias M, Norgren S, Janson A. Successful treatment of a cohort of infants with neonatal diabetes using insulin pumps including data on genetics and estimated incidence. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109:1131–7.

Zanfardino A, Piscopo A, Curto S, Schiaffini R, Rollato AS, Testa V, Miraglia Del Giudice E, Barbetti F, Iafusco D. Very low birth weight newborn with diabetes mellitus due to pancreas agenesis managed with insulin pump reservoir filled with undiluted insulin: 16-month follow-up. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2022;16: 102561.

Zanfardino A, Carpentieri M, Piscopo A, Curto S, Miraglia Del Giudice E, Inverardi A, Diplomatico M, Moschella S, Spagnuolo F, Caredda E, Montaldo P, Iafusco D. Sensor augmented pump therapy is safe and effective in very low birth weight newborns affected by neonatal diabetes mellitus, with poor subcutaneous tissue: replacement of the insulin pump infusion set on the arm, a video case report. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2022;16:254–5.

Passanisi S, Timpanaro T, Lo Presti D, Mammì C, Caruso-Nicoletti M. Treatment of transient neonatal diabetes mellitus: insulin pump or insulin glargine? Our experience. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2014;16:880–4.

Kurnaz E, Aycan Z, Yıldırım N, et al. Conventional insulin pump therapy in two neonatal diabetes patients harboring the homozygous PTF1A enhancer mutation: Need for a novel approach for the management of neonatal diabetes. Turk J Pediatr. 2017;59:458–62. https://doi.org/10.24953/turkjped.2017.04.013.

London S, De Franco E, Elias-Assad G, Barhoum MN, Felszer C, Paniakov M, Weiner SA, Tenenbaum-Rakover Y. Case report: neonatal diabetes mellitus caused by a Novel GLIS3 mutation in twins. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.673755.

Huggard D, Stack T, Satas S, Gorman CO. Donohue syndrome and use of continuous subcutaneous insulin pump therapy. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:5–8.

Rabbone I, Barbetti F, Marigliano M, Bonfanti R, Piccinno E, Ortolani F, Ignaccolo G, Maffeis C, Confetto S, Cerutti F, Zanfardino A, Iafusco D. Successful treatment of young infants presenting neonatal diabetes mellitus with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion before genetic diagnosis. Acta Diabetol. 2016;53:559–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-015-0828-7.

Fukuda Y, Ishii A, Kamasaki H, Fusagawa S, Terada K, Igarashi L, Kobayashi M, Suzuki S, Tsugawa T. Long-term sensor-augmented pump therapy for neonatal diabetes mellitus: a case series. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol. 2022;31:178–84.

Sakai R, Kikuchi N, Nishi D, Horiguchi H. Successful termination of insulin therapy in transient neonatal diabetes mellitus. Case Rep Pediatr. 2023;2023(11):6667330.

Lee MY, Gloyn AL, Maahs DM, Prahalad P. Management of neonatal diabetes due to a KCNJ11 mutation with automated insulin delivery system and remote patient monitoring. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2023;2023:8825724.

Mancioppi V, Pozzi E, Zanetta S, Missineo A, Savastio S, Barbetti F, Mellone S, Giordano M, Rabbone I. Case report: Better late than never, but sooner is better: switch from CSII to sulfonylureas in two patients with neonatal diabetes due to KCNJ11 variants. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1143736.

Wanaguru A, Phan P, Lim L, Verge C, Hameed S, Neville K. Advanced hybrid closed-loop use in children less than 2 years old with diluted insulin: a case series. Acta Diabetol. 2024;61(2):257–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-023-02218-5.

Rapini N, Delvecchio M, Mucciolo M, et al. The changing landscape of neonatal diabetes mellitus in Italy between 2003–2022. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109(9):2349–57. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgae095.

Besser RE, Flanagan SE, Mackay DG, et al. Prematurity and genetic testing for neonatal diabetes. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3): e20153926. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3926.

Klingensmith GJ. Use of insulin pump in neonates and toddlers. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17(12):857–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2015.0339.

Habeb AM, Deeb A, Elbarbary N, Beshyah SA. Diagnosis and management of neonatal diabetes mellitus: a survey of physicians’ perceptions and practices in ASPED countries. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;159: 107975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107975.

Chisnoiu T, Balasa AL, Mihai L, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring in transient neonatal diabetes mellitus-2 case reports and literature review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(13):2271. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13132271.

McKinlay CJD, Chase JG, Dickson J, Harris DL, Alsweiler JM, Harding JE. Continuous glucose monitoring in neonates: a review. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2017;3:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-017-0055-z.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for the publication of this article. The rapid service fee and/or open access fee were funded by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (Raffaella Panza, Valentina Cattivera, Jacopo Colella, Maria Elisabetta Baldassare, Manuela Capozza, Luca Zagaroli, Maria Laura Iezzi, Nicola Laforgia, Maurizio Delvecchio) contributed to the study conception and design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All the authors (Raffaella Panza, Valentina Cattivera, Jacopo Colella, Maria Elisabetta Baldassare, Manuela Capozza, Luca Zagaroli, Maria Laura Iezzi, Nicola Laforgia, Maurizio Delvecchio) do not declare any competing interests. Maurizio Delvecchio is an Editorial Board member of Diabetes Therapy. Maurizio Delvecchio was not involved in the selection of peer reviewers for the manuscript nor any of the subsequent editorial decisions.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Panza, R., Cattivera, V., Colella, J. et al. Insulin Delivery Technology for Treatment of Infants with Neonatal Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Ther (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-024-01653-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-024-01653-z