Abstract

Introduction

Effectively engaging people with type 2 diabetes (T2D) earlier in their health journeys is critical to prevent downstream complications. Digitally based diabetes programs are a growing component of care delivery that have the potential to engage individuals outside of traditional clinic-based settings and use personalized data to pair people to tailored diabetes self-management interventions. Knowing an individuals’ diabetes empowerment and health-related motivation can help drive appropriate recommendations for personalized interventions. We aimed to characterize diabetes empowerment and motivation towards changing health behaviors among participants in Level2, a T2D specialty care organization in the USA that combines wearable technology with personalized clinical support.

Methods

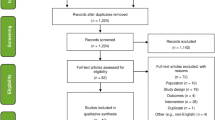

A cross-sectional online survey was conducted among people enrolled in Level2 (February–March 2021). Distributions of respondent-reported diabetes empowerment and health motivation were analyzed using Motivation and Attitudes Toward Changing Health (MATCH) and Diabetes Empowerment Scale Short Form (DES-SF) scales, respectively. Associations between MATCH and DES-SF scores with Level2 engagement measures and glycemic control were analyzed.

Results

The final analysis included 1258 respondents with T2D (mean age 55.7 ± 8.4 years). Respondents had high average MATCH (4.19/5) and DES-SF (4.02/5) scores. The average MATCH subscores for willingness (4.43/5) and worthwhileness (4.39/5) were higher than the average ability subscore (3.73/5). Both MATCH and DES-SF scores showed very weak correlations with Level2 engagement measures and glycemic control (ρ = − 0.18–0.19).

Conclusions

Level2 survey respondents had high average motivation and diabetes empowerment scores. Further research is needed to validate sensitivity of these scales to detect changes in motivation and empowerment over time and to determine whether differences in scores can be used to pair people to personalized interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Virtual or digitally based diabetes programs can deliver diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES) in more real time, to more geographically diverse populations than traditional care settings |

These digitally based programs have the potential to facilitate improved diabetes self-management behaviors by using personalized data to pair individuals to tailored interventions |

One opportunity to deliver personalized care at scale for people with T2D is to assess an individual’s baseline empowerment and readiness to engage in self-management techniques, using this to pair individuals to suitable personalized interventions |

This study aimed to better understand diabetes empowerment and health motivation among participants in Level2, a diabetes specialty care organization that combines wearable technology and personalized clinical support in the US |

What was learned from the study? |

Participants reported high average motivation and diabetes empowerment scores. The study provided insights about distribution of health motivation and empowerment |

Our study findings suggest that either MATCH or DES-SF may serve as useful tools for future studies or program evaluations |

Introduction

Treatment guidelines for type 2 diabetes (T2D) recommend a holistic, patient-centered approach to optimize glycemic control, manage weight, and mitigate cardiovascular/renal disease [1, 2]. Early glycemic control is the key to prevent downstream diabetes-related complications [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. However, persisting therapeutic inertia contributes to poor achievement of glycemic and cardiometabolic therapeutic goals [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes is an important component of diabetes care delivery, but successful implementation of T2D treatment recommendations remains a challenge in clinic-based settings [11,12,13]. Diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES) is a patient-centered model that focuses on improving patients’ knowledge, skill, and diabetes self-management ability [1, 7, 14, 15]. Although early use of DSMES has been shown to improve outcomes, evidence suggests that only 5–7% of people with T2D access DSMES offerings within 12 months of their diagnosis [16,17,18]. Furthermore, two-thirds of non-metropolitan counties in the USA do not have DSMES programs, limiting access for people with T2D [19].

A recent wave of virtual or digitally based diabetes programs now provides more real-time and geographically diverse access to DSMES-like interventions outside of clinic-based settings. These often include access to other facets of diabetes care, like no-cost blood glucose meters and individualized coaching using mobile medical applications and in, some cases, no-cost continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and care providers [12, 15, 20,21,22,23]. Digitally based DSMES-like interventions delivered at scale across large populations have the potential to offer personalized interventions that could improve diabetes self-management and even start to become a standard offering to people with diabetes [21, 24]. Therefore, it is critical that assessment of these programs occurs with a focus on the ability to tailor future diabetes care to meet this aspirational direction.

One opportunity for virtual or digitally based DSMES-like programs to deliver personalization at scale is to accurately assess an individual’s baseline empowerment (individuals having self-awareness to manage their diabetes and improve quality of life) and readiness to engage in self-management techniques and then pair individuals to suitable personalized interventions [15, 21, 23, 25,26,27]. Examples of matching DSMES interventions include identifying patient characteristics or preferences (learning style, literacy, numeracy, language, culture, physical challenges, scheduling challenges, social determinants of health, and financial concerns) and then offering individualized programs tailored to their unique needs [23].

Two validated questionnaires, Diabetes Empowerment Scale Short Form (DES-SF), which is a measure of diabetes-related psychosocial self-efficacy, and Motivations and Attitudes Toward Changing Health (MATCH), can provide insight into an individual’s self-reported empowerment and motivation [28, 29]. The DES-SF has been used in cross-sectional surveys and clinical studies to measure the impact of interventions on diabetes empowerment [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. While DES-SF is specific to diabetes, MATCH is designed to assess general attitudes towards changing health behaviors, regardless of clinical condition [28, 29]. The MATCH scale includes nine questions across three subscales related to components of change and consists of a comprehensive score and three subscores for perceived willingness, worthwhileness, and ability [28]. Willingness reflects the intention of patients towards making changes, worthwhileness measures their perceived worthiness of the expected outcomes, and ability reflects self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control [28].

This study aimed to characterize the distributions of MATCH and DES-SF scores among participants with T2D enrolled in Level2, a diabetes specialty care organization that combines wearable technology and personalized clinical support in the US [46]. It also aimed to characterize the associations between MATCH and DES-SF scores with clinical features and Level2 engagement features to better understand health motivation and diabetes empowerment of participants. People with T2D who opt into Level2 for their diabetes management represent a digitally engaged group [46]. Engagement includes the use of wearable devices and viewing data insights and leveraging tools within the Level2 app. In addition, Level2 participants can engage virtually with coaches and/or clinicians and receive personalized activity recommendations. Recruiting from this population enabled the study of MATCH and DES-SF in the context of a digitally based DSMES-like program, where patients can engage with lesser burden than in a typical clinic-based setting. This enabled assessment of MATCH and DES-SF scores in a virtual context as potential tools for digital health program evaluations as well as DSMES content personalization.

Methods

Study Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted in partnership with Level2, a T2D specialty care organization that is part of UnitedHealth Group (UHG) [46]. Level2 offers an optional program to people with T2D aged ≥ 18 years who meet certain clinical eligibility requirements and have an eligible insurance plan across the US. Participants who are invited, have given consent, and have activated wearable devices have the ongoing opportunity to wear a no-cost CGM and/or fitness tracker. Participants enrolled in the Level2 program can: view data insights and leverage tools within the Level2 app; engage virtually with coaches and/or clinicians; and receive personalized activity recommendations to help manage their diabetes. All enrollees in Level2 who met the eligibility criteria were sent an invitation via email to participate in a one-time online survey (February–March 2021). The survey link was available to each participant for up to 2 weeks, and the estimated time for participants to respond to the survey questions was ≤ 10 min. The survey included an informational page and consent page to join the study, followed by the nine MATCH scale questions and eight DES-SF questions [28, 29]. The consent and study procedures followed the International Conference of Harmonization’s (ICH) and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines. This study was reviewed and determined to qualify for exemption by authorized regulatory representatives on behalf of the UHG Institutional Review Board (UHG OHRA Certificate of Action #2021-0020). This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Study Participants

Participants were recruited from a population of people with T2D from across the US who were already enrolled in Level2. To ensure a diverse sample of Level2 participants for this survey, the selection criteria were broad with no exclusions based on program engagement or clinical features. Adults with T2D enrolled in Level2 who had provided an email address for Level2 outreach were considered eligible for the survey and were invited to participate. Participants then self-selected into the opportunity to consent, enroll, and provide survey answers in English. Employees of UHG were not eligible to participate in the survey.

Study Outcomes

The primary objective was to characterize the distributions of MATCH and DES-SF scores among Level2 participants. The secondary objectives were to describe the associations between MATCH and DES-SF scores with Level2 program enrollment duration, duration of T2D, measures of Level2 engagement (CGM wear, days of available CGM data, number of coaching interactions, and number of Level2 healthy activities completed), and glycemic control [time in range (TIR), glucose management indicator (GMI), and self-reported HbA1c]. The demographic profile of the survey participants was also summarized.

Data Sources and Study Variables

In addition to the survey response data, Level2 program data (including enrollment, engagement, self-reported duration of diabetes, self-reported HbA1c, and CGM-derived glucose measures: TIR and GMI) and participants’ historical administrative medical and pharmacy claims data were available. Datasets were secured by Optum Labs and complied with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) guidelines.

The observed variables were Level2 enrollment duration, number of coaching visits, number of completed recommended healthy activities reported, self-reported T2D duration, and self-reported HbA1c. The number of coaching visits and completed recommended healthy activities (e.g., walking after a meal or replacing a sugary beverage with a zero-calorie option) spanned from August 1, 2020, to April 1, 2021. HbA1c reports occurred between December 2019 and August 2021 and were not temporally aligned with each other across individuals. CGM variables were defined using an individual’s total available CGM data from January 1, 2021, to March 31, 2021, and included the presence or absence of CGM data, number of days of CGM data, TIR, and GMI. Historical medication use was obtained from pharmacy claims data between January 1, 2021, and March 31, 2021.

Scoring for MATCH and DES-SF Scales

Total MATCH score was calculated based on the mean of the three MATCH subscores (willingness, ability, and worthwhileness). If any of the subscores were missing, then the MATCH score was not calculated. Each MATCH subscore was calculated as mean of three questions and was not calculated if a respondent skipped two or more questions in any subscore section. Both surveys were graded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The total DES-SF score was summarized as the mean of all completed DES-SF components.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective did not involve hypothesis tests as it was descriptive in nature. As such, the sample size was not set to a pre-specified power calculation. Adjustments for multiplicity were not made. Therefore, any p values to accompany study correlations would be regarded as exploratory and thus were not reported in the results or tables to prevent overinterpretation. The a priori goal for the study was to recruit around 500 participants or approximately 10% of the eligible Level2 respondent population.

Means and standard deviations were used to describe the distributions of MATCH and DES-SF scores. The t test was used to compare the mean MATCH scores and mean DES-SF scores of the two groups, where one group was composed of the respondents with available CGM data and the other group was respondents with no associated CGM data. Cohen’s d (effect size) was used to present the standardized mean differences of MATCH and DES-SF scores between respondents with and those without CGM data. Spearman’s correlation coefficient (ρ) along with the 95% confidence interval (CI) was used for continuous explanatory variables (e.g., Level2 enrollment duration and T2D duration). p values are not reported, and multiple testing corrections were not performed. All the data were analyzed using Python version 3.7.0.

Results

Respondent Demographics

Of the 1314 people who consented to the survey, 1258 (96%) had sufficient data for both MATCH and DES-SF scores to be calculated (non-completers n = 56). Supplementary Table (S1) describes the email outreach campaign for the survey. Fifty-one percent of the survey respondents were female (Table 1). Overall, the mean age of the respondents was 55.7 ± 8.4 years; 73% of the respondents were between 50 and 69 years of age (Table 1). Respondents were geographically clustered in the US South (47.0%) and Midwest (35.5%) regions and reflected the geographic distribution of the general Level2 population (Table 1). Based on claims history, the most frequently filled diabetes medication classes were metformin (62.2%), glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA; 30.1%), sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor (SGLT-2; 22.5%), long- and intermediate-acting insulins (19.9%), and sulfonylurea (18.5%) (Table 1). Most respondents had filled one or two diabetes medication classes (56.3%), while others had filled three classes (17.0%) or four or more classes (10.4%) in the 3-month period prior to and inclusive of the survey period (Table 1).

Distribution of MATCH and DES-SF Scores

The average MATCH score (4.19 out of 5) was high among the respondents who completed the survey (Fig. 1). Within the MATCH subscores, respondents scored higher in their willingness to do more to manage their health (average willingness subscore: 4.43; Table 2) and their perception that making health-related changes were worthwhile (average worthwhileness subscore: 4.39; Table 2). However, they scored lower in feeling they were able to make and sustain health-related changes (average ability subscore 3.73; Table 2). Similar to the MATCH score, the average DES-SF score (4.02 out of 5) was high among the respondents who completed the survey (Fig. 1). Moderate correlations were observed between the MATCH and DES-SF scores [ρ 0.49, 95% CI (0.44,0.53); Table 2; Fig. 2].

Association of MATCH and DES-SF Scores with Level2 Engagement Variables

The mean self-reported diabetes duration was 11.0 ± 7.7 years, and the mean self-reported HbA1c was 7.1%. The average duration of enrollment in Level2 was 6.8 ± 5.9 months. On average, the respondents had 1.8 coaching encounters and self-reported completion of a recommended healthy activity of at least 58 times. A significant, albeit very weak, association was observed between the DES-SF score and duration of Level2 enrollment [ρ = 0.07, 95% CI (0.02, 0.13)] and number of coaching visits [ρ = 0.08, 95% CI (0.02, 0.13)]. A significant, albeit very weak, correlation was also observed between the number of self-reported completed healthy activities and MATCH score [ρ = 0.07, 95% CI (0.02, 0.13)] and DES-SF score [ρ = 0.11; 95% CI (0.05, 0.16)] (Table 3).

Association of MATCH and DES-SF Scores with CGM Variables

A total of 1124 respondents (89%) had associated CGM data, averaging almost 50 days of data (Table 4). The average TIR and GMI of the respondents were 76.9% and 7.0%, respectively, indicative of well-controlled diabetes. The MATCH score was positively associated with better glucose control via TIR [ρ = 0.10, 95% CI (0.04, 0.15)] and GMI [ρ = − 0.09, 95% CI (− 0.15, − 0.03)]. A higher DES-SF score was associated with more days of CGM wear [ρ = 0.08, 95% CI (0.02, 0.13)] and better glucose control via TIR [ρ = 0.19, 95% CI (0.13, 0.25)] and GMI [ρ = − 0.18, 95% CI (− 0.24, − 0.12)] (Table 4).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study of health-related motivation and diabetes empowerment among Level2 participants was conducted as part of a T2D specialty care organization which supplements traditional clinic-based diabetes care. To the authors’ knowledge, this study is the largest reported to collect both MATCH and DES-SF scores. Respondents appeared to be an engaged T2D population as indicated by active participation in Level2 (e.g., coaching and health activities), good glucose control [high TIR (~ 77%) among those with data], and high proportions of no-cost CGM wear (89.3%). High engagement was also demonstrated by an unexpectedly high proportion of respondents interested in being contacted with future research opportunities (90.1%).

The current study found high average motivation scores (4.19) among our survey respondents, which is slightly higher than a previous study of MATCH (4.00) in a population of people with T2D [28]. This may indicate that Level2 participants have slightly higher self-reported motivation than the general population with T2D. In a pattern similar to one observed in the MATCH validation study, the current study also found that the MATCH subscores for willingness (4.25) and worthwhileness (3.96) were higher than the ability score (3.81) [28]. MATCH subscore differences may serve as a useful fingerprint of an individual’s unique health-related motivational state. A lower ability score may indicate that respondents would be best matched with interventions that offer more practical assistance for making changes or that are targeted to increase self-efficacy towards self-management of T2D using interventions such as problem solving therapy [22]. Similarly, a lower willingness score might indicate motivational interviewing or that coaching could benefit that respondent [22]. However, to date, there is no published research that assesses the impact of using MATCH subscores to pair people to targeted interventions.

Participants in our study had high empowerment scores (mean DES-SF score: 4.02), consistent with previous studies including the original DES validation study (mean DES score 3.91–3.96) [29,30,31, 34,35,36, 39,40,41,42,43, 47]. Prior studies have been conducted in other settings outside of Level2, with some reporting positive associations between higher DES-SF scores and better glycemic control and older age (65–75 years; DES-SF score ≥ 4) [30,31,32]. DEF-SF scores were higher in people with active self-management behaviors, i.e., self-efficacy scores increased 1.25 times for every unit increase in DES-SF scores [33].

Additionally, prior studies in other settings found that higher DES-SF scores are associated with higher levels of social support and higher usage of a digital remote monitoring platform [34, 41]. Other clinical and real-world studies showed changes in DES scores before and after an intervention, suggesting that this could be used as an evaluation tool for DSMES programs or other interventions [39,40,41,42]. For example, in one published study, 61% of the participants had improvement in mean DES-SF scores from 3.90 (pre-intervention) to 4.30 (post-intervention) [40]. Similarly, in another study, the mean DES-SF scores improved over a 6-month period [3.4 (baseline) to 4.1 (6 months)] [43]. A clustered randomized controlled trial showed an increase in the median DES-SF score among those in a home visit intervention group from 4.0 to 4.2 [48].

Both MATCH and DES-SF scores correlated with similar number of Level2 engagement variables. DES-SF was slightly more sensitive to establish relationships with additional variables than MATCH was, specifically duration of Level2 enrollment, number of coaching sessions, and days of CGM data. The observed correlations with Level2 variables were generally low; the associations were statistically significant but may not be clinically meaningful, particularly among a highly engaged group where the range of score distributions is narrow. This could also be attributed to psychosocial or socioeconomic factors that were not accounted for in this study, as study variables were limited to demographics, clinical features, and program engagement features. Nevertheless, the results were intuitive in demonstrating that respondents who self-reported higher motivation and empowerment had greater engagement in health-related activities (Level2 participation and CGM wear) and better glycemic control (higher TIR and lower GMI).

In general, MATCH and DES-SF provide complementary information, as DES-SF endpoints are specific to diabetes while MATCH endpoints are not. While originally validated among a population with T2D, MATCH is designed to assess general health motivations. Therefore, MATCH may offer the opportunity to explore differences in health motivation across a spectrum of conditions. The latest waves of diabetes digital health interventions and drug therapies often receive multiple indications that extend beyond glucose control and into the treatment of obesity and other cardiometabolic conditions [49, 50]. The incorporation of measurement tools beyond those specifically designed for diabetes-related endpoints may be one strategy for holistic comorbidity evaluations, particularly when assessing interventions that confer multi-factorial improvements in markers of general or cardiometabolic health.

Based on our findings for both MATCH and DES-SF scales, incorporating one or both instruments into a digital DSMES-like program provides an opportunity to leverage patient-reported data to personalize content or treatment. It can also provide insights into how different dimensions of motivation may conceptually inter-relate and ultimately contribute to behavior change. Opportunities for future research exists, such as prospectively testing how interventions impact MATCH and DES-SF scores over time, how interventions could be tailored to an individual’s baseline MATCH and DES-SF scores or unique MATCH subscore profile, and whether profile-tailored approaches are associated with enhanced engagement, persistence, and clinical benefit compared with non-tailored approaches. Similarly, such an approach could be applied to program design for DSMES-like interventions by using motivation and empowerment scores to route patients to tailored program pathways that meet their current perceived state. The consistent baseline and follow-up use of digital surveys across diabetes interventions, programs, and pathways could accelerate our understanding of how-to best pair people with T2D to the care that best works for them.

Strengths and Limitations

The survey comprised the largest population of people with T2D in the US to complete both the MATCH and DES-SF tools to the authors’ knowledge. Additionally, ease of data collection through the Level2 digital platform is noteworthy, with > 1200 survey responses collected over a period of 2 weeks, which was three times larger than the population sizes in the original MATCH and DES validation studies [28, 29]. The study included a decentralized and geographically diverse group of people across a range of ages with varying durations of T2D. The survey responses were complemented using data from multiple sources such as program engagement data, CGM data, and historical claims data. However, the study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, all findings were associative and not causal. Second, features of the study design contributed to a selection bias that shifted the responder population to a group of engaged people with T2D that may not be generalizable to a broader population. Those features included: (1) completion of consent, activation of no-cost wearable devices, and subsequent Level2 participation as primary filters for engagement; (2) an online format of the survey and email-based invitation selecting for a digitally engaged group; (3) high proportions of CGM wear (89.3%) and interest in future research (90.1%) indicative of a deviation from what would be expected in the general population. Additionally, respondents had generally well-controlled glucose, were most commonly filling two or fewer diabetes medication classes, and averaged 55.7 ± 8.4 years of age with mean self-reported duration of diabetes 11.0 ± 7.7 years, and the surveys were only distributed in English. Therefore, findings may not generalize to populations with lower glucose control (TIR/GMI), different age ranges, durations of diabetes, or insurance status, lower willingness to enroll and engage in digital-first diabetes programs, or people whose primary language is not English. Furthermore, select variables (e.g., HbA1c and duration of diabetes) were self-reported, not temporally aligned across all participants, and not available for all survey respondents. The survey was only given at a single timepoint, leaving us unable to remark on how responses may change over time. Additionally, some important demographic features, including self-reported education status and income, were not assessed. Finally, all medication information was derived from pharmacy claims, which does not equate to taking medications as prescribed and does not account for medications obtained via alternate channels (e.g., cash payment for low-cost generics).

Conclusions

This study provides insight into the cross-sectional distribution of health motivation (measured by MATCH) and diabetes empowerment (measured by DES-SF) in a digitally engaged T2D population in the US. It indicates how Level2 program engagement and clinical features are weakly associated with higher MATCH and DES-SF scores. Either MATCH or DES-SF may serve as useful tools for future studies or program evaluations. Choosing only one tool could reduce the burden of questions on respondents, but each provides useful information depending on the goals of the study, intervention, or program. Additional research is needed to validate whether MATCH and DES-SF are sensitive enough to detect changes in motivation and empowerment following a digital intervention and whether scores can be used to pair people to personalized interventions.

References

American Diabetes Association. Introduction: standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:S1–2. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-Sint.

American Diabetes Association. 7. Diabetes technology: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:S77–88. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-S007.

Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, et al. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2643–53. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa052187.

Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352:837–53

Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, et al. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1577–89. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0806470.

Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2560–72. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0802987.

Andreozzi F, Candido R, Corrao S, et al. Clinical inertia is the enemy of therapeutic success in the management of diabetes and its complications: a narrative literature review. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2020;12:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-020-00559-7.

Okemah J, Peng J, Quiñones M. Addressing clinical inertia in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review. Adv Ther. 2018;35:1735–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0819-5.

Fang M, Wang D, Coresh J, et al. Trends in diabetes treatment and control in U.S. adults, 1999–2018. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2219–28. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa2032271.

Khunti K, Wolden ML, Thorsted BL, et al. Clinical inertia in people with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study of more than 80,000 people. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3411–7. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-0331.

Gabbay RA, Kendall D, Beebe C, et al. Addressing therapeutic inertia in 2020 and beyond: a 3-year initiative of the American Diabetes Association. Clin Diabetes. 2020;38:371–81. https://doi.org/10.2337/cd20-0053.

Mata-Cases M, Franch-Nadal J, Gratacòs M, et al. Therapeutic inertia: still a long way to go that cannot be postponed. Diabetes Spectr. 2020;33:50–7. https://doi.org/10.2337/ds19-0018.

Khunti S, Khunti K, Seidu S. Therapeutic inertia in type 2 diabetes: prevalence, causes, consequences and methods to overcome inertia. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2019;10:2042018819844694. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042018819844694.

Davis J, Fischl AH, Beck J, et al. 2022 national standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Sci Diabetes Self Manag Care. 2022;48:44–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/26350106211072203.

American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 5. Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:S60–82. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-S005.

American Diabetes Association. 5. Lifestyle management: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:S46–60. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-S005.

Li R, Shrestha SS, Lipman R, et al. Diabetes self-management education and training among privately insured persons with newly diagnosed diabetes–United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1045–9.

Strawbridge LM, Lloyd JT, Meadow A, et al. Use of medicare’s diabetes self-management training benefit. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42:530–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198114566271.

Rutledge SA, Masalovich S, Blacher RJ, et al. Diabetes self-management education programs in nonmetropolitan counties—United States 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66:1–6. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6610a1.

Kamrudin S, Clark C, Mondejar JP, et al. 695-P: engagement and glycemic outcomes over 24 weeks among new level2 members. Diabetes. 2022. https://doi.org/10.2337/db22-695-P.

Draznin B, Aroda VR, Bakris G, et al. 1. Improving care and promoting health in populations: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:S8–16. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-S001.

Carpenter R, DiChiacchio T, Barker K. Interventions for self-management of type 2 diabetes: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Sci. 2019;6:70–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.12.002.

Powers MA, Bardsley JK, Cypress M, et al. Diabetes self-management education and support in adults with type 2 diabetes: a consensus report of the American Diabetes Association, the Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of PAs, the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, and the American Pharmacists Association. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:1636–49. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci20-0023.

Chatterjee S, Davies MJ, Heller S, et al. Diabetes structured self-management education programmes: a narrative review and current innovations. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:130–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(17)30239-5.

Piccinino LJ, Devchand R, Gallivan J, et al. Insights from the national diabetes education program national diabetes survey: opportunities for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Spectr. 2017;30:95–100. https://doi.org/10.2337/ds16-0056.

Łuczyński W, Głowińska-Olszewska B, Bossowski A. Empowerment in the treatment of diabetes and obesity. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:5671492. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5671492.

Funnell MM, Anderson RM. Empowerment and self-management of diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2004;22:123–7. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaclin.22.3.123.

Hessler DM, Fisher L, Polonsky WH, et al. Motivation and attitudes toward changing health (MATCH): a new patient-reported measure to inform clinical conversations. J Diabetes Complications. 2018;32:665–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2018.04.009.

Anderson RM, Fitzgerald JT, Gruppen LD, et al. The diabetes empowerment scale-short form (DES-SF). Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1641–2. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.26.5.1641-a.

Fitzgerald M, O’Tuathaigh C, Moran J. Investigation of the relationship between patient empowerment and glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008422. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008422.

Rossi MC, Lucisano G, Funnell M, et al. Interplay among patient empowerment and clinical and person-centered outcomes in type 2 diabetes. The BENCH-D study. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:1142–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.05.012.

Simonsen N, Koponen AM, Suominen S. Empowerment among adult patients with type 2 diabetes: age differentials in relation to person-centred primary care, community resources, social support and other life-contextual circumstances. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:844. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10855-0.

Yao J, Wang H, Yin X, et al. The association between self-efficacy and self-management behaviors among Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0224869. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224869.

Gonzalez MB, Herman KA, Walls ML. Culture, social support, and diabetes empowerment among American Indian adults living with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2020;33:156–64. https://doi.org/10.2337/ds19-0036.

Cheng L, Leung DY, Sit JW, et al. Factors associated with diet barriers in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:37–44. https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.S94275.

Holmes-Truscott E, Skinner TC, Pouwer F, et al. Negative appraisals of insulin therapy are common among adults with type 2 diabetes using insulin: results from diabetes MILES—Australia cross-sectional survey. Diabet Med. 2015;32:1297–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12729.

Tol A, Baghbanian A, Mohebbi B, et al. Empowerment assessment and influential factors among patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2013;12:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/2251-6581-12-6.

Tang TS, Funnell MM, Brown MB, et al. Self-management support in “real-world” settings: an empowerment-based intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79:178–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.029.

McGloin H, O’Connell D, Glacken M, et al. Patient empowerment using electronic telemonitoring with telephone support in the transition to insulin therapy in adults with type 2 diabetes: observational, pre-post, mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e16161. https://doi.org/10.2196/16161.

Bollyky J, Lu W, Painter SL, et al. 914-P: connected glucose meter plus CDE coaching improves diabetes patient empowerment and distress in real-world outcomes setting. Diabetes. 2019. https://doi.org/10.2337/db19-914-P.

Perez-Nieves M, Lu W, Poon JL, et al. 83-LB: are activation, behaviors, and attitudes to managing care Associated with utilization of a remote diabetes monitoring platform (RDMP) and improvement of A1C? Diabetes. 2020. https://doi.org/10.2337/db20-83-LB.

Petersson C, Nygårdh A, Hedberg B. To support self-management for people with long-term conditions—the effect on shared decision-making, empowerment and coping after participating in group-learning sessions. Nurs Open. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1261.

Bollyky JB, Bravata D, Yang J, et al. Remote lifestyle coaching plus a connected glucose meter with certified diabetes educator support improves glucose and weight loss for people with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:3961730. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3961730.

Yang H, Gao J, Ren L, et al. Association between knowledge-attitude-practices and control of blood glucose, blood pressure, and blood lipids in patients with type 2 diabetes in shanghai, China: a cross-sectional study. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:3901392. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3901392.

Wang X, Lyu W, Aronson R, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the LMC Skills, Confidence & Preparedness Index (SCPI) in patients with type 2 diabetes. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01664-x.

Innovative New Level2™ digital health therapy resulted in better health for people with type 2 diabetes. Press release. UnitedHealth Group; July 13, 2020. Accessed 3 Feb 2022. https://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/newsroom/2020/2020-7-13-level2-digital-health-therapy-type2-diabetes.html.

Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Fitzgerald JT, et al. The diabetes empowerment scale: a measure of psychosocial self-efficacy. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:739–43. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.23.6.739.

Souza D, Aparecida S, Reis IA, et al. Evaluation of home visits for the empowerment of diabetes self-care. Acta Paul Enferm. 2017;30:350–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0194201700052.

Levine BJ, Close KL, Gabbay RA. Reviewing U.S. connected diabetes care: the newest member of the team. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2020;22:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2019.0273.

Brown E, Heerspink HJL, Cuthbertson DJ, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists: established and emerging indications. Lancet. 2021;398:262–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00536-5.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and Rapid Service and Open Access Fees were funded by Eli Lilly and Company. The use of DES-SF was supported by grant number P30DK020572 (MDRC) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

The authors thank our Level2 participants and Level2 collaborators, without whom this work would not have been possible. The authors also appreciate Jessyca Duerr for her contributions to writing, revising, and critical review of the comprehensive technical report accompanying this work. Medical writing support was provided by Uma Jyothi Kommoju, PhD, an employee of Eli Lilly Services India Private Limited, India.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Elizabeth L. Eby, Callahan N. Clark, Brian D. Benneyworth, Ron Hoffner, and Brian Hart contributed to conception, design, and interpretation of data. Cody J. Lensing, Ron Hoffner, and Nanette C. Schloot contributed to design and interpretation of the data. Brian Hart and Lilian Lingcaro were involved in the analysis of the data. Elizabeth L. Eby, Callahan N. Clark, Nanette C. Schloot, Brian D. Benneyworth, and Elena Fultz were involved in drafting the manuscript and critical revision. All the authors were involved in interpretation of the data and critical revision for the intellectual content.

Disclosures

Elizabeth L. Eby, Nanette C. Schloot, and Brian D. Benneyworth are employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. Callahan N. Clark and Lilian Lingcaro are full-time employees of UnitedHealth Group and own stock in the company. Ron Hoffner was an employee of Level2 at the time of this research and Cody Lensing, Elena Fultz, and Brian Hart were employees of UnitedHealth Group at the time of this research; all owned stock in UnitedHealth Group company during employment. Ron Hoffner is currently working as an independent consultant for Hoffner Insights, LLC. Cody Lensing is currently a full-time employee of Terumo BCT, Inc. Elena Fultz is currently a full-time employee of Anselm House. Brian Hart is currently a full-time employee of Natera.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was reviewed and determined to qualify for exemption by the UHG Office of Human Research Affairs on behalf of the UHG Institutional Review Board (UHG OHRA Certificate of Action #2021-0020). This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to regulatory obligations. The study results were not presented anywhere prior to publishing in this journal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Cody J. Lensing, Elena Fultz, Brian Hart and Ron Hoffner have changed affiliation since the time this research was conducted. Assigned affiliation is the institution of employment at the time this research was conducted.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Clark, C.N., Eby, E.L., Lensing, C.J. et al. Characterizing Diabetes Empowerment and Motivation for Changing Health Behaviors Among People with Type 2 Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Diabetes Ther 14, 869–882 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-023-01397-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-023-01397-2